Abstract

Among 684 sexually active women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) followed up for a mean of 35 months, we related contraceptive use to self-reported PID recurrence, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility. Persistent use of condoms during the study reduced the risk of recurrent PID, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility. Consistent condom use (about 60% of encounters) at baseline also reduced these risks, after adjustment for confounders, by 30% to 60%. Self-reported persistent and consistent condom use was associated with lower rates of PID sequelae.

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), the clinical condition representing inflammation of the pelvic organs, is common1 and can result in PID recurrence, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility.2,3 Prevention of the bacterial sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) that cause PID is a cornerstone of efforts to reduce morbidity from PID and its sequelae.4,5

Condom use prevents acquisition of viral STDs, including HIV. However, because no prospective data show that condoms are effective against transmission of bacterial STDs,6 controversy surrounds their use in primary prevention.7,8

Within the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health Study, a multicenter, follow-up study of women with PID,9 we assessed the relation between condom use and PID-related morbidity.

METHODS

The methods of subject recruitment, data collection, and follow-up have been reported elsewhere.9,10 In brief, women aged 14 to 37 years were recruited from 13 US sites between March 1996 and February 1999. Enrolled women met clinical criteria for suspected PID, including pelvic discomfort, pelvic organ tenderness, leukorrhea, mucopurulent cervicitis, and untreated gonococcal or chlamydial cervicitis. This analysis includes the 684 women who were sexually active at baseline and who had at least 1 follow-up visit.

In a standardized in-person interview, we asked about the use of oral contraceptives, hormonal implants or injections, intrauterine devices (used by only 15 women and thus not reported), diaphragms, spermicides, cervical caps, female condoms, and male condoms by a partner. More than 1 method could be selected. About half (53%) of the women reported baseline use of barrier methods of contraception, 92% of which was condom use. Condom use was considered to be consistent if a woman reported use with at least 6 of the last 10 sexual encounters.

Every 3 to 4 months, telephone interviews were repeated. Follow-up information was available for 85% of the cohort after a mean of 35 months. Outcomes included (1) self-reported recurrent PID (subsequent to the baseline episode), with medical record verification (in 68% of cases); (2) chronic pelvic pain, defined as consistent self-reports of at least 6 months’ duration; and (3) infertility, defined as the proportion of women without a β–human chorionic gonadotropin–confirmed pregnancy among the subgroup of women who reported no effective contraception (no contraception, natural family planning, or rhythm method) or rare use of barrier contraception for an aggregate of at least 12 months.

Baseline differences between groups were analyzed with χ2 tests. Frequencies and unadjusted relative risks of recurrent PID, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility were calculated by comparing use with nonuse of condoms and consistent with nonconsistent use of condoms at each follow-up time point. Persistence (the percentage of all interviews in which condoms were used) was divided into quartiles. Analyses were repeated to compare women reporting use of condoms alone (without concurrent use of another method) with those reporting use of no effective method (including withdrawal, natural family planning, and none). Finally, we calculated the risks of outcomes among users and nonusers of other methods of contraception.

Separate logistic regression models for each outcome adjusted for age (continuous), number of live births (continuous), educational attainment (did not complete high school, high school graduate or equivalent, any education beyond high school), race (Black, White, other), nonmonogamy at baseline (yes or no), new partner in the past month at baseline (yes or no), gonococcal or chlamydial cervicitis at baseline (yes or no), number of study visits (continuous), and other methods of contraception. Adjusted odds ratios, derived from these models, estimated the adjusted relative risks.

RESULTS

Most of the women enrolled in the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health cohort were Black (74%), were aged 24 years or younger (66%), and had no more than a high school education (76%). Cervical infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae was identified in 15% of the women, Chlamydia trachomatis was identified in 16%, and both were found in 6%.

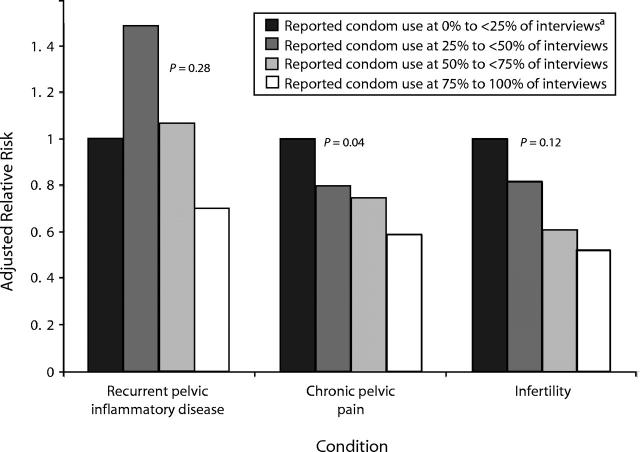

Rates of recurrent PID, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility were highest among nonpersistent condom users (25% to less than 50% of reports) and lowest among persistent condom users (75%–100% of reports) (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Adjusted relative risks for each condition, by percentage of interviews at which condom use was reported.

Note. P values are for trend.

aReference group.

After adjustment for covariates, the relative risks for consistent condom users compared with nonusers were 0.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.3, 0.9) for recurrent PID, 0.7 (95% CI = 0.5, 1.2) for chronic pelvic pain, and 0.4 (95% CI = 0.2, 0.9) for infertility (Table 1 ▶). Users of other barrier methods were at reduced risk, albeit nonsignificant, for developing recurrent PID. Use of oral contraceptives or medroxyprogesterone was not associated with significantly elevated or reduced risks of the PID sequelae studied.

TABLE 1—

Percentages of and Relative Risks (RRs) for Recurrent Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID), Chronic Pelvic Pain, and Infertility After an Episode of PID, by Contraceptive Method Use in the 4 Weeks Prior to Baseline: 1996–1999

| Condition | ||||||||||||

| Recurrent PID | Chronic Pelvic Pain | Infertility | ||||||||||

| n | % | RR | Adjusted RRa (95% CI) | n | % | RR | Adjusted RRa (95% CI) | n | % | RR | Adjusted RRa (95% CI) | |

| Condoms | ||||||||||||

| No | 324 | 16.7 | 1.0 | 300 | 36.7 | 1.0 | 132 | 54.5 | 1.0 | |||

| ≤ 5–10 times | 156 | 16.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.5) | 142 | 31.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) | 59 | 45.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.5) |

| ≤ 6–10 times | 204 | 8.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 (0.3, 0.9) | 187 | 26.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 (0.5, 1.2) | 46 | 34.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 (0.2, 0.9) |

| Other barrierb | ||||||||||||

| No | 650 | 14.8 | 1.0 | 597 | 32.7 | 1.0 | 226 | 48.7 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 34 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.02, 1.1) | 32 | 28.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 (0.3, 1.7) | 11 | 45.5 | 0.9 | 1.2 (0.3, 4.8) |

| Oral contraceptives | ||||||||||||

| No | 606 | 14.4 | 1.0 | 556 | 33.1 | 1.0 | 217 | 47.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 78 | 12.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 (0.4, 1.8) | 73 | 27.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 (0.4, 1.4) | 20 | 65.0 | 1.4 | 3.2 (1.1, 9.4) |

| Medroxyprogesterone | ||||||||||||

| No | 605 | 14.5 | 1.0 | 556 | 33.3 | 1.0 | 214 | 50.9 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 79 | 11.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.2) | 73 | 26.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 (0.3, 0.9) | 23 | 26.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 (0.2, 1.4) |

| No effective methodc | ||||||||||||

| No | 453 | 12.1 | 1.0 | 416 | 26.8 | 1.0 | 134 | 41.8 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 231 | 18.2 | 1.5 | 1.4 (0.5, 3.6) | 213 | 39.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 (0.8, 3.6) | 103 | 57.3 | 1.4 | 2.3 (0.6, 8.3) |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

aAdjusted for age, number of live births, race, nonmonogamy at baseline, new partner at baseline, gonococcal or chlamydial cervicitis at baseline, education, number of study visits, and all other forms of contraception other than that under consideration.

bDiaphragms, spermicides, cervical cap, or female condom.

cNo contraception, natural family planning, or withdrawal.

Similar associations were found when comparing women who, at baseline, reported use of only a single method of contraception with women who reported use of no effective contraceptive method (data not shown). For example, adjusted relative risks for consistent condom use compared with use of ineffective methods were 0.6 for recurrent PID, 0.6 for chronic pelvic pain, and 0.3 for infertility. Excluding women who reported a history of PID at baseline, restricting our analysis to women with baseline evidence of endometritis or gonococcal or chlamydial upper genital tract infection, and including only recurrent PID based on verified medical record reports had little effect on these estimates.

DISCUSSION

A limited number of cross-sectional and case–control studies have examined the effectiveness of condoms in preventing the acquisition of N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis among women, with mixed results.11–19 An additional 2 case–control studies and 1 cross-sectional study reported reductions in the occurrence of PID and tubal infertility among condom users, but this was significant in only 1 study.20–22

This analysis of the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health cohort lends strength to the literature on condom use and the prevention of PID and its sequelae. This study had several strengths: reports of condom use preceded the occurrence of outcomes, sample size was large, adjustment for confounding was made, a geographically diverse cohort was enrolled, and outcomes were validated.

The greatest weakness of this analysis was the reliance on self-report for contraceptive use, which may have resulted in an underestimation of the true association.16,23 Concurrent use of spermicides also may have reduced the observed protective effect because nonoxynol 9–containing spermicides may facilitate the risk for acquisition of STDs.24

These prospective data support the use of condoms for the prevention of PID sequelae.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants HS08358-05 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and AI 48909-07 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Human Participant Protection Human subjects approval was obtained at each participating institution, and all women gave informed consent.

Contributors R. B. Ness conceived the study and supervised all aspects of its implementation. H. Randall, H. E. Richter, J. F. Peipert, A. Montagno, D. E. Soper, R. L. Sweet, D. B. Nelson, D. Schubeck, and S. L. Hendrix supervised and conducted study implementation. D. C. Bass and K. E. Kip completed analyses and assisted with the study. All authors helped to conceptualize ideas and interpret findings and reviewed drafts of the brief.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.National Survey of Family Growth. In: Vital and Health Statistics: Data From the National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, Md: Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics; 1995.

- 2.Westrom L. Incidence, prevalence, and trends of acute pelvic inflammatory disease and its consequences in industrialized countries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138:880–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westrom L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, Hagdu A, Thompson SE. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility: a cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westrom L, Eschenbach D. Pelvic inflammatory disease. In: Holmes K, Mardh P, Sparling P, et al, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:783–809.

- 5.Eng TR, Butler WT, eds. The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Disease. Washington, DC: Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed]

- 6.Workshop summary: scientific evidence on condom effectiveness for sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention. Paper presented at: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health; 2000; Herndon, Va.

- 7.Mann JR, Stine CC, Vessey J. The role of disease-specific infectivity and number of disease exposures on long-term effectiveness of the latex condom. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cates W. The condom forgiveness factor: the positive spin. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:350–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: results from the Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ness RB, Soper DE, Peipert J, et al. Design of the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Study. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:499–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg MJ, Davidson AJ, Chen JH, Judson FN, Douglas JM. Barrier contraceptives and sexually transmitted diseases in women: a comparison of female-dependent methods and condoms. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:669–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin H, Louv WC, Alexander J. A case–control study of spermicides and gonorrhea. JAMA. 1984;251:2822–2824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters SE, Beck-Sague CM, Farshy CE, et al. Behaviors associated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis: cervical infection among young women attending adolescent clinics. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39:173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaydos CA, Howell MR, Pare B, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infections in female military recruits. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radcliffe DW, Ahmad S, Gilleran G, Ross JDC. Demographic and behavioural profile of adults infected with Chlamydia: a case–control study. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:265–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zenilman JM, Weisman CS, Rompalo AM, et al. Condom use to prevent incident STDs: the validity of self-reported condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joesoef MR, Linnan M, Barakbah Y, Idajadi A, Kambodji A, Schulz K. Patterns of sexually transmitted diseases in female sex workers in Surabaya, Indonesia. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paris M, Gotuzzo E, Goyzueta G, et al. Prevalence of gonococcal and chlamydial infections in commercial sex workers in a Peruvian Amazon City. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortenberry JD, Brizendine EJ, Katz BP, Wools KK, Blythe MJ, Orr DP. Subsequent sexually transmitted infections among adolescent women with genital infection due to Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or Trichomonas vaginalis. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelaghan J, Rubin GL, Ory HW, et al. Barrier-method contraceptives and pelvic inflammatory disease. JAMA. 1982;248:184–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cramer DW, Goldman MB, Schiff I, et al. The relationship of tubal infertility to barrier method and oral contraceptive use. JAMA. 1987;257:2446–2450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, et al. Hormonal and barrier contraception and risk of upper genital tract disease in the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellish NJ, Weisman CS, Celentano D, Zenilman JM. Reliability of partner reports of sexual history in a heterosexual population at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 1996;23:446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonoxynol-9 spermicide contraception use—United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]