Abstract

Objectives. I examined the effect of imposing a requirement for parental consent before minors can receive medical contraceptives.

Methods. Birth and abortions among teens, relative to adults, in a suburban Illinois county that imposed a parental consent requirement in 1998 were compared with births and abortions in nearby counties during the period 1997–2000.

Results. The relative proportion of births to women under age 19 years in the county rose significantly compared with nearby counties, whereas the relative proportion of abortions to women under age 20 years declined insignificantly, with a relative increase in the proportion of pregnancies (births and abortions) to young women in the county.

Conclusions. Imposing a parental consent requirement for contraceptives, but not abortions, appears to raise the frequency of pregnancies and births among young women.

Family planning clinics that receive federal funds under Title X of the Public Health Service Act are required to provide services without regard to age or marital status.1 Several court decisions during the 1970s and 1980s affirmed that no clinic receiving such funds may require parental consent or notification before providing birth control services to unmarried minors.2 However, in recent years Congress and several state legislatures have considered requiring publicly funded clinics to involve parents before providing contraceptives to minors. This study examined the effect on births and abortions among minors of 1 such parental involvement requirement.

In April 1998, McHenry County, Illinois, began requiring parental consent before providing minors with contraceptives at the only public health clinic in the county. Because the policy violates Title X, the county now uses its own funds to pay for contraceptives services at the clinic for eligible adults and minors who have parental consent. The clinic refers teens who do not wish to involve their parents to facilities in nearby counties. McHenry County is the first county known to have ended its involvement with Title X to impose a parental consent requirement for contraceptives. The fertility effects of such a policy are unknown, as no previous study has examined the effects of a parental involvement requirement for contraceptives on minors’ pregnancy rates in the United States. Related literature about the effect of requiring parental involvement for minors seeking abortions has reached mixed conclusions about the effects on birth and abortion rates.3,4

The expected effects of such a parental consent requirement on minors’ pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates are ambiguous. Pregnancy rates would rise if some individuals who would have used medical contraceptives, absent the parental consent requirement, would now use less-effective means of birth control, or no contraception at all, but continue to have sex. Abortions, birth rates, or both would then rise as well. Alternatively, pregnancy, abortion, and birth rates would be unaffected if all teens who would have used medical contraceptives in the absence of the requirement were to obtain parental consent and there were no changes in sexual and contraceptive behavior among other teens. Pregnancy, abortion, and birth rates might even decline if imposing a parental consent requirement for contraceptives caused some minors to abstain from intercourse.

Surveys of minors indicate that many would change their behavior if parental consent for contraceptives were required. A substantial fraction of young women—nearly half—said they would stop visiting family planning clinics if a parental consent requirement were imposed. The majority of these minors indicate they would switch to condoms or other nonprescription forms of birth control, but some said that they would stop using any form of contraception though continuing to have intercourse.5–7 In addition, a small fraction of teens indicate they would not have sex if faced with a parental consent requirement for medical contraceptives.6,7

This study applies quasi-experimental methods to estimate the effect of the parental consent requirement for medical contraceptives imposed in McHenry County. The analysis compares the change in the percentage of abortions and births to young women in that county with the corresponding change in nearby counties. The results indicate that, in the 2 years after the parental consent requirement, the percentage of births to women under age 19 years in the county rose by 0.69 percentage points relative to other counties, and that the relative percentage of pregnancies (births and abortions) to women under age 20 years in the county rose by 0.76 percentage points. The findings imply that the parental consent requirement for contraceptives raised pregnancy and birth rates among minors but did not significantly affect abortion rates.

METHODS

This study uses natality data from the National Center for Health Statistics and abortion data from the State of Illinois Department of Public Health to examine the effect of the parental consent requirement in McHenry County. The National Center for Health Statistics natality data, which are at the individual level, are a near census of births and include women’s age at birth and their county of residence. Illinois does not make available individual-level data on abortions but does report the annual number of abortions by county of residence and age within certain age categories for cells that have at least 50 abortions.

This analysis compares McHenry County with 3 counties that are large enough to have abortion data available and that also are near McHenry County: DuPage, Kane, and Lake. McHenry County is a suburban community located about 50 miles northwest of Chicago; DuPage, Kane, and Lake Counties are also north or western suburbs of Chicago. McHenry County is predominately white (94%, according to the 2000 census) and had a median household income of $64 826 in 1999; about 3.7% of individuals had incomes below the poverty level in 1999. The nearby comparison counties are also majority white (95%) and had about 4.8% of individuals living below the poverty threshold in 1999. In 1997, Title X–funded clinics in the 3 comparison counties served a slightly higher proportion (9.1%) of women under age 20 years in need of publicly funded contraceptive services than did the clinic in McHenry (7.3%).8 Data for Cook County, which includes the city of Chicago, are also available but are not used here because Cook County is considerably poorer, more minority, and more urban than McHenry County. Data for several other large counties in Illinois are also available but are not used here because these counties are not near McHenry and therefore may not be comparable.

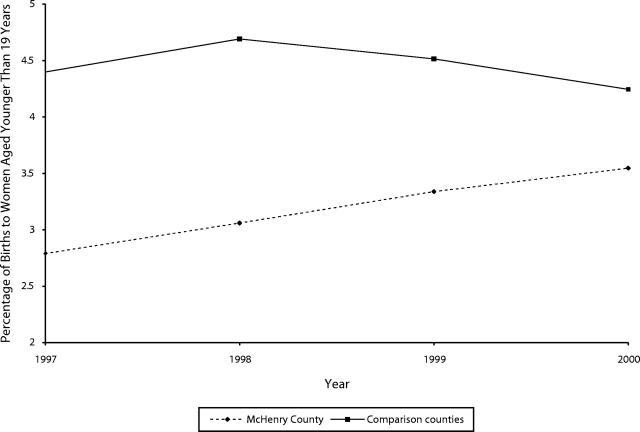

Figure 1 ▶ shows the number of births among women aged 18 years and younger as a percentage of all births in McHenry County and in 3 nearby comparison counties during 1997–2000. The proportion of births to young women increased during this period in McHenry County. In the comparison counties, the percentage of births to young women rose from 1997 to 1998 and then declined; from 1999–2000 the parental consent law was in effect in McHenry County but not in the other counties.

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of births that were to women younger than 19 years in McHenry County and in nearby counties, 1997–2000.

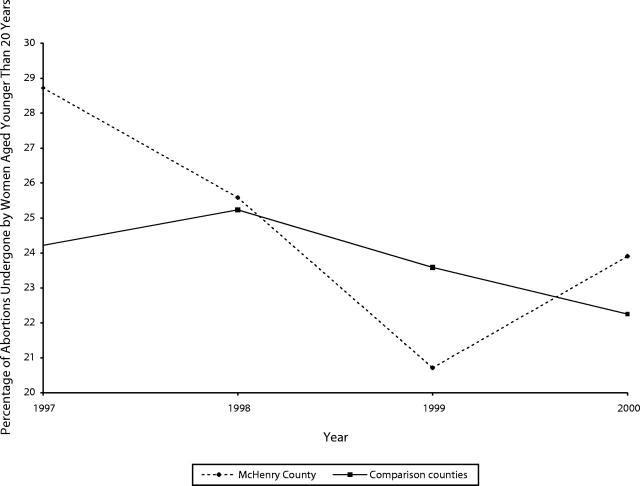

Figure 2 ▶ shows abortions among women under age 20 years (the only available age group that includes minors) relative to all abortions for McHenry and the nearby comparison counties. The percentage of abortions that were undergone by teenaged women in McHenry County fell between 1997 and 1999 and then increased. In the comparison counties, the proportion of abortions that were undergone by teenaged women rose slightly during 1997–1998 and then declined. The percentage of abortions undergone by young women (< 20) may be more volatile in McHenry than in the other counties because the numbers are small, averaging only 117 abortions per year to teenaged women in McHenry County during 1997–2000 compared with over 700 in the 3-county comparison area.

FIGURE 2—

Percentage of abortions that were undergone by women younger than 20 years in McHenry County and in nearby comparison counties, 1997–2000.

Difference-in-Differences Analysis

The remainder of this analysis uses a difference-in-differences technique to examine the effect of the parental consent requirement for contraceptives on births and abortions.9 This technique involves comparing the change in births and abortions for the affected group (the treatment group) with an unaffected group. Here, the affected group is minors who reside in McHenry County. These young women are compared with older women who live in the same county by measuring births and abortions among young women as a percentage of all births and abortions. The first difference in the difference-in-differences analysis is the change in the proportion of births and abortions to young women before and after the parental consent policy went into effect. This difference is then compared with the corresponding change in the other counties. The statistical significance of the differences is calculated using standard t tests on the standard errors of the differences. The percentage of births and abortions to young women, rather than to the population at risk, is examined because intercensal population estimates by age group are not available at the county level.

The period 1997–1998 is the “before” period, and 1999–2000 the “after” period, in the difference-in-differences analysis. The parental consent requirement went into effect in April 1998, so any effect on births should begin in 1999. Any effect on abortions would likely begin to occur in 1998, but only annual data on abortions are available. Another concern about the abortion data are that ages 0–19 years are the only age group for minors available in the abortion data, but 19-year-old women were not directly affected by the parental consent requirement. In the births data, females aged 18 years and younger serve as the treatment group here because many women aged 18 years at birth were minors when they became pregnant.

The difference-in-differences approach has several advantages. First, it compares births and abortions before and after the parental consent policy within McHenry County. The methodology also controls for changes in underlying conditions that would have the same effect on the number of births and abortions across all age groups in 1 county—such as a change in the number of abortion providers in McHenry County—by comparing across age groups within a county. In addition, the methodology controls for differential changes in births and abortions between young women and all women by comparing McHenry County with other counties. The only requirement for the difference-in-difference method to be properly identified is that there not be different changes in fertility behavior of young women relative to older women in McHenry County relative to other counties during the sample period other than the changes caused by the parental consent requirement. During the 1997–2000 sample period, there were no changes in policies regarding parental involvement for minors to receive an abortion or minors’ right to consent to pregnancy care in the counties examined here or in the state as a whole. Illinois did not have a parental involvement requirement for minors seeking abortions. Some teens may have misunderstood the policy in McHenry County as restricting access to abortions, which would lead to an increase in births but not necessarily in pregnancies; focus groups conducted with US teens indicate that few know whether their state requires parental involvement for a minor to have an abortion.10

Difference-in-Differences Results

The percentage of births to women under age 19 years rose in McHenry County after the parental consent policy relative to the nearby comparison counties. As the first row of Table 1 ▶ indicates, the percentage of births to young women rose by 0.52 percentage points in McHenry County between 1997–1998 and 1999–2000 but declined by 0.16 percentage points in the comparison counties, giving a relative increase of 0.69 percentage points in McHenry County. The difference-in-differences result is statistically significant, with a P value below .05. In results not shown in the table, the increase in the fraction of births to women under age 19 years in McHenry County is significant relative to DuPage and Kane Counties separately (each with a P value below .03), as well as in comparison with the 3-county area.

TABLE 1—

Change in Percentage of Births to and Abortions Undergone by Young Women in McHenry County Compared with Nearby Counties

| “Before” Period (1997–1998) | “After” Period (1999–2000) | Difference | DD | |||||

| Percentage | SE | Percentage | SE | Percentage | SE | Percentage | SE | |

| Births to women aged younger than 19 y | ||||||||

| McHenry County | 2.92 | .19 | 3.44 | .20 | .52 | .28 | — | — |

| Comparison countiesa | 4.54 | .08 | 4.38 | .08 | −.16 | .12 | .69 | .30 |

| Abortions undergone by aged women younger than 20 y | ||||||||

| McHenry County | 27.07 | 1.55 | 22.29 | 1.25 | −4.78 | 1.97 | ||

| Comparison countiesa | 24.73 | .60 | 22.86 | .51 | −1.86 | .78 | −2.92 | 2.12 |

| Births to and abortions undergone by aged women younger than 20 y | ||||||||

| McHenry County | 4.50 | .23 | 5.07 | .23 | .57 | .32 | — | — |

| Comparison countiesa | 6.53 | .10 | 6.34 | .09 | −.19 | .13 | .76 | .35 |

Note. DD = difference-in-difference. Shown are the differences between the percentage of births or abortions to young women in McHenry and the comparison counties in each year, relative to the corresponding differences in the baseline year of 1997, expressed in percentage terms.

aThe comparison counties are DuPage, Kane, and Lake.

The percentage of abortions to women under age 20 years declined in McHenry County after the parental consent policy, both absolutely and relative to the comparison counties. As the middle section of Table 1 ▶ shows, the percentage of abortions to teenaged women fell by 4.78 percentage points in McHenry County and by 1.86 percentage points in the 3-county comparison group. The relative decline in abortions to young women in McHenry County is therefore 2.92%, but it is not significant at conventional levels (P = .17). In results not shown in the table, the decline in the proportion of abortions to young women in McHenry is significant relative to Lake County separately (P < .05), but not relative to either DuPage or Kane County.

The effect of McHenry County’s parental consent requirement may have increased over time because the accumulated risk of pregnancy rose over time among minors who switched to less effective means of contraception or stopped using any birth control while continuing to have intercourse; in other words, not all persons would become pregnant soon after the policy went into effect, but over time the probability of pregnancy would increase. Alternatively, the effect may have decreased over time as minors who did not obtain parental consent found other means of getting medical contraceptives, such as visiting a private provider or a clinic in another county, or as minors received parental consent. If the policy discouraged teens not yet sexually active from having intercourse, the effect also might be to reduce birth and abortion rates over time.

The first row in Table 2 ▶ shows the change in the percentage of births to women under age 19 years in McHenry County compared with nearby counties, relative to the 1997 baseline. The relative proportion of births to young women was 0.43 percentage points higher in McHenry County in 1999 than in 1997 compared with the corresponding change in the 3-county area, but the change was insignificant (P = .37). In 2000, the relative difference increased to 0.91 percentage points (P = .06) compared with 1997. This indicates that the effect of the parental consent requirement increased over time. In addition, the relative change in 1998 was −0.02 percentage points and was not significant (P = .97), indicating that the rise in births to young women in McHenry County did not begin before the policy could have affected births.

TABLE 2—

Percentage Change in Births to and Abortions Undergone by Young Women in McHenry County Compared With Nearby Countiesa, Relative to Difference in 1997

| 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | ||||

| Percentage | SE | Percentage | SE | Percentage | SE | |

| Births to women aged younger than 19 y | −.02 | .49 | .43 | .49 | .91 | .49 |

| Abortions undergone by women aged younger than 20 y | −4.15 | 3.20 | −7.38 | 3.02 | −2.85 | 3.02 |

| Births to and abortions undergone by women aged younger than 20 y | −.48 | .49 | .12 | .48 | .76 | .48 |

a The nearby counties are DuPage, Kane, and Lake.

The percentage of abortions to young women in McHenry County declined in all 3 years, relative to 1997, in comparison with the nearby counties. Row 2 in Table 2 ▶ reports the comparisons, which indicate that the relative decline in abortions to teenaged women in McHenry was largest in 1999 and was insignificant in 1998 and in 2000.

Taken together, the births and abortions data indicate that teen pregnancies rose after McHenry County imposed a parental consent requirement. Combining the data on abortions and pregnancies, the proportion of pregnancies, measured as births plus abortions, to women under age 20 years was 0.76 percentage points (P = .05) higher during 1999–2000 than in 1997–1998 in McHenry County relative to the nearby comparison counties, as the bottom row of Table 1 ▶ indicates. The positive effect appears to be concentrated during 2000, as shown in the last row of Table 2 ▶. However, it should be recognized that all teens under age 20 years are not the most relevant group to examine because women aged 18 and 19 years are not directly affected by the parental consent policy.

One potential concern about our results is that the policy could have had effects in 1998. Any such effect is likely to be concentrated on abortions because terminations occur in pregnancy, but births also could have been affected if some teens anticipated that the policy would be enacted. Assigning 1996–1997 as the “before” period would avoid capturing any effects that occurred soon after the policy went into effect. In results not shown in the tables, the relative decline in births to women under age 19 years was 0.63 percentage points (P = .09) if 1996–1997 is used as the “before” period. The relative change in abortions was −4.46 percentage points (P = .03), and the relative change in pregnancies was 0.32 percentage points (P = .41). Similar to the results that used 1997–1998 as the “before” period, these findings indicate that the policy had a positive effect on births; however, they also indicate a negative effect on abortions and no significant effect on pregnancies.

Another concern about the findings is that defining all women as an implicit control group may be inappropriate because older women’s fertility behavior may differ considerably from that of minors. Women slightly above age 18 years may be a better comparison group. If the births analysis is repeated with only births to women under age 25 years used, the percentage of births to women under age 19 years in McHenry County increased by 2.81 percentage points (P = .06) from 1997–1998 to 1999–2000 compared with the 3 nearby counties. The percentage of abortions to women under age 20 years among all women under age 25 years declined by 1.89 percentage points in McHenry County relative to the nearby comparison counties; as in Table 1 ▶, the relative change is statistically insignificant (P = .58). Pregnancies to women under age 20 years as a proportion of all pregnancies to women under age 25 years rose by 3.02 percentage points (P = .05) in McHenry County relative to the nearby comparison counties. Comparing teens with only slightly older women therefore gives results qualitatively similar to those when comparing teens to all women.

DISCUSSION

Proponents offer several reasons why parental involvement should be required before minors may receive contraceptives. Parents may wish to be aware of their children’s sexual activity and may want to discuss with their children the potential health risks associated with some prescription contraceptives. Some proponents argue that requiring parental notification would increase minors’ use of condoms, thereby reducing the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, or their use of abstinence, which would also reduce teenaged pregnancy rates. Opponents of such requirements frequently argue that such policies will increase teen pregnancy rates because some minors will switch to less effective contraceptives or continue having intercourse but not use any birth control.

This study indicates that pregnancies and births among young women increased in a county that imposed a parental consent requirement for contraceptives. In the 2 years after McHenry County, Illinois, enacted a parental consent requirement, the percentage of births to women under age 19 rose by 0.69 percentage points relative to other counties, and the percentage of births plus abortions to women under age 20 years rose by 0.76 percentage points. The proportion of abortions to teenaged women declined but was statistically insignificant. The true effect of the policy on abortions among women young enough to have been affected by the policy is difficult to ascertain because data on abortions specifically among women aged 18 years and younger are not available. The abortion data used here are for women aged 0–19 years, which includes women too old to have been directly affected by the policy.

It should also be noted that this study examines only 1 suburban, predominately White community, and that the results may not be generalizable to other areas. In particular, contraceptive clients at publicly funded family planning clinics are disproportionately from low-income and minority groups.11,12 This indicates that the effect of a parental involvement requirement might be greater in more urban areas than in the suburban area investigated here. However, 1 study found that Black minors were less likely than Whites to say that they would stop using family planning clinic services if their parents were notified, so such a policy could instead have less of an effect in other areas.5

Title X is believed to have substantially reduced teen pregnancy rates by making free or low-cost family planning services available to teens on a confidential basis. One analysis concluded that, without Title X, the number of teenaged pregnancies would have been 20% higher during the 1980s and 1990s.13 A significant number of minors seek family planning services at Title X clinics; in 1991, for example, about 14% of patients—over 580 000 individuals—were minors.14 This study examined the 1 area known to have imposed a parental consent requirement for minors to receive medical contraceptives and found that teen pregnancies, particularly teen births, appear to increase after such a requirement. This suggests that policymakers should consider the possibility of such unintended consequences before requiring parental involvement for teens to receive contraceptives.

A parental consent policy may also affect other aspects of teens’ sexual health, such as pregnancy testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases. One recent study conducted among minors at Planned Parenthood clinics in Wisconsin found that 47% of minors said that they would stop using all family planning clinic services if their parents were notified that they were seeking birth control pills or other contraceptive devices, and another 12% would delay testing or treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy testing, or other services.5 These are important areas for further research.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Title X, Public Health Services Act, 42 USC.§§ 300–300a-8.

- 2.Donovan P. Challenging the teenage regulations: the legal battle. Fam Plann Perspect. 1983;15:126–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cartoof VG, Klerman LV. Parental consent for abortion: impact of the Massachusetts law. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:397–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas-Wilson D. The economic impact of state restrictions on abortion: parental consent and notification laws and Medicaid funding restrictions. J Policy Anal Manage. 1993;12:498–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy DM, Fleming R, Swain C. Effect of mandatory parental notification on adolescent girls’ use of sexual health care services. JAMA. 2002;288:710–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres A. Does your mother know ...? Fam Plann Perspect. 1978;10:280–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres A, Forrest JD, Eisman, S. Telling parents: clinic policies and adolescents’ use of family planning and abortion services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1980;12:284–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alan Guttmacher Institute. Family Planning Services in the US in the Late 1990’s: State and County Data. 2001. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute.

- 9.Meyer BD. Natural and quasi-natural experiments in economics. J Bus Econ Stat. 1995;13,151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone R, Waszak C. Adolescent knowledge and attitudes about abortion. Fam Plann Perspect. 1992;24:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frost JJ, Bolzan M. The provision of public-sector services by family planning agencies in 1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 1997;29:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost JJ. Public or private providers? US women’s use of reproductive health services. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold RB. Title X: Three decades of accomplishment. Guttmacher Rep Publ Policy. 2001;4:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith JC, Franchino B, Henneberry JF. Surveillance of family planning services at Title X clinics and characteristics of women receiving these services, 1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]