Abstract

Objectives. We assessed weapon use in intimate partner violence and perspectives on hypothetical firearm policies.

Methods. We conducted structured in-person interviews with 417 women in 67 battered women’s shelters.

Results. Words, hands/fists, and feet were the most common weapons used against and by battered women. About one third of the battered women had a firearm in the home. In two thirds of these households, the intimate partner used the gun(s) against the woman, usually threatening to shoot/kill her (71.4%) or to shoot at her (5.1%). Most battered women thought spousal notification/consultation regarding gun purchase would be useful and that a personalized firearm (“smart gun”) in the home would make things worse.

Conclusions. A wide range of objects are used as weapons against intimate partners. Firearms, especially handguns, are more common in the homes of battered women than in households in the general population.

More than 1.5 million physical or sexual assaults are committed by current or former intimate partners each year in the United States, and 1 in 4 women report having been harmed by an intimate partner during their lifetime.1 About one half of the female victims sustain an injury, but only about 20% of those who are injured seek medical treatment.2 Even so, US emergency departments treat nearly 250 000 patients—mostly women—annually for injuries inflicted by an intimate partner.2 Women injured by intimate partners account for about 1 in 5 hospital emergency department visits for intentional injury.2

Because weapons increase the ability to inflict harm, it would be useful to know more about objects that are used as weapons against intimate partners. Far less is understood about the means than about the results (i.e., the medical outcomes) of weapon-related violence. Of particular interest are firearms, because they have a higher case fatality rate than other means of inflicting assaultive injury.3,4 In addition, firearms are among the few weapons that are subject to purchase or possession restrictions.

The primary objectives of the present study were twofold: (1) to investigate the range of weapons used and the relative frequency with which weapons are used against intimate partners and (2) to describe firearm prevalence and use in intimate partner violence. In addition, we assessed battered women’s perspectives on firearm-related policies that would affect them directly. To obtain such information, we interviewed residents of battered women’s shelters—women who were likely to be representative of those who have experienced substantial amounts of violence and who have had various objects used against them by an intimate partner.

METHODS

Sample Recruitment and Data Collection

Structured in-person interviews were sought with women staying in 84 emergency shelters for battered women across California. The 84 shelters constituted the population of emergency shelters then funded by the California Department of Health Services. Permission to conduct interviews with residents of emergency shelters was first sought from each agency’s executive director and then sought from shelter residents themselves. Shelters that agreed to participate were given a $125 certificate for domestic violence prevention training materials, regardless of whether residents of the shelter participated. Participating residents were offered a $25 grocery store certificate for their time.

Executive directors of 72 agencies (86%) gave permission for residents of their emergency shelters to be interviewed. Residents of 67 of the 72 shelters (93%) were eligible (i.e., were aged at least 18 years and spoke English or Spanish) and agreed to participate in the study. RoperASW (Princeton, NJ), a national survey research firm, conducted the 417 interviews during May through August 2001. Most (77.8%) were conducted in English, 18.1% were in Spanish, and 4.2% used a combination of both; interviews averaged 19 minutes each.

Interview Content

The first set of questions focused on the types of weapons that had ever been used against the respondent by an intimate partner, by the respondent to harm her partner, or by the respondent in self-defense. Because we were interested in both injury and noninjury outcomes, the questions specified weapon use intended to hurt, to scare, or to intimidate. After identifying the person of interest and motive for use (e.g., the respondent, use in selfdefense), the interviewer read the same list of potential weapons, which included an “other” option.

The second area focused on firearms within the context of the woman’s most recent relationship—that is, the relationship the woman was in before she entered the shelter. The questions included firearm ownership by the woman’s partner, whether a firearm was kept in the home, and the use of guns within the context of the relationship. If the 2 partners had not lived together (and only 7.9% had not), we asked about guns in each residence and tabulated responses across the 2 households. In addition, the woman’s perspective was sought regarding firearm-related manufacture and distribution innovations not currently available in the United States—that is, personalized firearms (“smart guns”) and spousal notification/consultation regarding firearm purchases.

Survey development included refining questions with a focus group of battered women, pretesting, and pilot testing. The final questionnaire was translated into Spanish and translated back into English, and minor changes were made to ensure equivalency of the forms.

RESULTS

Respondent Characteristics

For two thirds (67.9%) of the respondents, this was their first stay at an emergency shelter for battered women; for 17.5%, it was their second stay. Most of the respondents (57.1%) had been at the shelter for 3 weeks or less. Most (69.6%) had children with them at the shelter; one third (31.4%) had children staying elsewhere.

Most of the respondents were members of minority groups: 36.9% were Hispanic, 15.7% were Black, 12.8% were of another ethnicity, and 34.7% were White. Two thirds (66.8%) were US natives, 20.4% were born in Mexico, and 12.8% were born elsewhere. The average age was 33 years (range: 18–69 years). About one third (36.2%) of the respondents were married, 42.3% were living with but not married to their partner, 13.5% were separated or divorced, and 8.0% reported another relationship status. About one third (36.4%) had less than a high school education, 27.7% had graduated from high school, 27.5% had some college education, and 8.4% had graduated from college. Almost half (44.4%) of the respondents were employed outside the home (28.0% full-time, 16.4% part-time), 37.4% were housewives, and 18.1% had another employment status. The typical respondent was poor. Almost half (42.4%) reported an annual household income of less than $15 000, 23.4% reported $15 000–$29 999, and 13.3% reported $25 000–$39 999; few (9.9%) reported an annual income of $40 000 or more. Eleven percent (11.1%) said that they did not know their household income.

Lifetime Weapons Use in Intimate Partner Violence

Against battered women.

The first column of Table 1 ▶ lists objects that had ever been used as a weapon by an intimate partner to hurt, threaten, or scare the respondent. Almost all of the respondents had had words and hands or fists used against them. The majority had had a door (e.g., slammed against body or limb) or wall (e.g., they were shoved against a wall), feet, or some type of household object used against them. Household objects identified most often were telephones or telephone cords (19.9%), pots/pans (9.8%), and plates/dishes (9.4%). Other objects used against the respondents included, but were not limited to, ashtrays, brooms, furniture, knives (nonkitchen), pillows, scissors, bottles, and irons. Among the 22.8% who reported that an intimate partner had used a tool against them, hammers and screwdrivers were most commonly reported (41.1% and 36.8%, respectively). Wrenches, pliers, and axes were among the other tools specified. More than one third reported that an intimate partner had used a motor vehicle as a weapon against them.

TABLE 1—

Objects Used by an Intimate Partner to Hurt, Scare, or Intimidate or in Self-Defense: 417 Residents of 67 California Battered Women’s Shelters

| Used by Respondent | |||

| Used by Partner to Hurt Respondent, % | to Hurt Partner, % | to Defend Self, % | |

| Weapon Type | |||

| Hands or fists | 96.9 | 19.2 | 79.3 |

| Feet | 65.7 | 7.7 | 54.2 |

| Words | 98.3 | 49.9 | 82.2 |

| Door or wall | 71.5 | 3.5 | 28.5 |

| Belt | 25.2 | 0.5 | 2.9 |

| Kitchen knife | 34.4 | 4.1 | 15.4 |

| Other household object (e.g., telephone, pan, ashtray) | 56.8 | 6.2 | 25.0 |

| Machete | 9.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Tool (e.g., hammer, screwdriver) | 22.8 | 0.7 | 5.1 |

| Car, pickup truck, or other vehicle | 37.4 | 4.6 | 18.2 |

| Long gun | 15.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| Handgun | 32.1 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| Other | 21.8 | 3.1 | 5.5 |

| No. of types of weapons | |||

| Mean ±SD | 5.9 ±2.6 | 1.0 ±1.4 | 3.2 ±1.9 |

| Range | 1–13 | 0–11 | 0–11 |

Note. Objects are listed in the order that respondents were asked about them. Missing data were rare (< 0.01% on each question).

Among the 36.7% who reported that a firearm had been used against them, victimization by a handgun was reported twice as often as that by a long gun. Whether a firearm was used against the respondent was positively associated with the number of weapons used (t test = 17.1, P < .001). Women who had been victimized with a firearm and those who had never been victimized with a firearm reported that an average of 8.1 and 4.6 types of weapons had been used against them, respectively.

By battered women against an intimate partner.

Battered women were substantially less likely to use a weapon against an intimate partner than to have it used against them (see the second column of Table 1 ▶). Words were the most common weapon used against a partner, followed by hands or fists, feet, and household objects. Few of the women had used a motor vehicle or a firearm against an intimate partner.

By battered women in self-defense.

Although few women had used objects as weapons to harm an intimate partner, it was common for them to have used objects in self-defense (see the third column of Table 1 ▶). The use of words, hands or fists, and feet was common. A substantial minority had used a door or wall, household object, or motor vehicle in self-defense.

Few of the respondents reported having used a gun in self-defense. There was some overlap between using a gun in self-defense and using a gun in aggression. Of the 15 women who had used a firearm in self-defense, 5 had also used a firearm aggressively against a partner. Of the 6 who had used a gun aggressively against a partner, 5 also had used the gun in self-defense.

Firearms in Most Recent Relationship

Firearm ownership by the partner.

Two fifths (39.1%) of the respondents reported that their most recent partner owned a gun during the time of the relationship. (Few [3.8%] said that they did not know whether their partner owned a gun.) Among the 163 respondents whose partner owned a firearm, 53.4% reported that he obtained a firearm during the time of the relationship. Most respondents (66.9%) reported that the partner’s having a gun made them feel less safe; 11.7% reported feeling more safe, and 8.0% reported feeling safer at first but less safe later. One third (35.0%) of the partners who had a gun had more than 1.

Firearm presence in the home.

About one third (36.7%) of respondents reported that they had a gun in their home at some point during the time of the relationship with their most recent partner. Most reported that having a gun in the home made them feel less safe (79.2%), but some said that they felt safer (11.7%) or safer at first but less safe later (5.8%).

As shown in Table 2 ▶, only 2 of the measured respondent characteristics were associated with having a gun in the home. The odds of having a firearm in the home was higher for women with a college education than for those with a high school education (adjusted odds ratio = 2.16, P < .006) and for US-born women than for immigrant women (adjusted odds ratio = 1.84, P < .03). Adding the number of weapons used against the woman improved the fit of the model, and for every additional weapon ever used against the woman, the odds of having a gun in the home increased by 1.38.

TABLE 2—

Predictors of Having a Firearm in the Home: 417 Residents of 67 California Battered Women’s Shelters

| AOR (95% CI) | ||

| Model Incorporating Demographic Characteristics Only | Model Incorporating Demographic Characteristics and No. of Weapons | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic (vs White) | 1.07 (0.59, 1.93) | 1.10 (0.58, 2.07) |

| Black | 0.67 (0.35, 1.31) | 0.63 (0.31, 1.29) |

| Other | 0.78 (0.38, 1.58) | 0.77 (0.36, 1.64) |

| US born (vs immigrant) | 1.84* (1.05, 3.24) | 1.25 (0.69, 2.27) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Living with (vs married) | 0.78 (0.47, 1.28) | 0.84 (0.49, 1.43) |

| Separated or divorced | 0.82 (0.41, 1.64) | 0.69 (0.33, 1.44) |

| Other relationship | 0.47 (0.18, 1.19) | 0.41 (0.15, 1.10) |

| Education | ||

| < High school (vs high school) | 0.86 (0.49, 1.51) | 0.72 (0.39, 1.31) |

| College | 2.16** (1.25, 3.72) | 2.21** (1.23, 3.95) |

| Workforce status | ||

| Working part-time (vs full-time) | 1.00 (0.52, 1.93) | 1.17 (0.58, 2.35) |

| Housewife | 0.85 (0.50, 1.47) | 0.90 (0.51, 1.61) |

| Other working | 1.21 (0.63, 2.32) | 1.37 (0.68, 2.77) |

| Children in home during past year (vs no) | 1.43 (0.81, 2.52) | 1.47 (0.80, 2.68) |

| No. of weapons used against the woman (lifetime) | 1.38* (1.25, 1.53) | |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

*P < .05; **P < .01.

Handguns were more common than long guns. Among the 153 households containing a firearm, 54.3% had handguns only, 12.4% had long guns only, and 30.7% had both handguns and long guns. A few (4) respondents reported that they did not know what kind of gun was in the home.

The average number of firearms in homes with at least 1 gun was 3.8 (SD = 9.2). The average number of handguns and long guns in a household was 2.5 (range: 0–50; median: 1) and 2.2 (range: 0–50; median: 1), respectively. Eleven (0.7%) of the women with a gun in the home reported that 10 or more guns were kept in the home. Most (78.0%) of the women with a gun in the home knew where the gun was kept (or where all guns were kept); 17.0% said that they did not know where the gun was kept (or where any guns were kept).

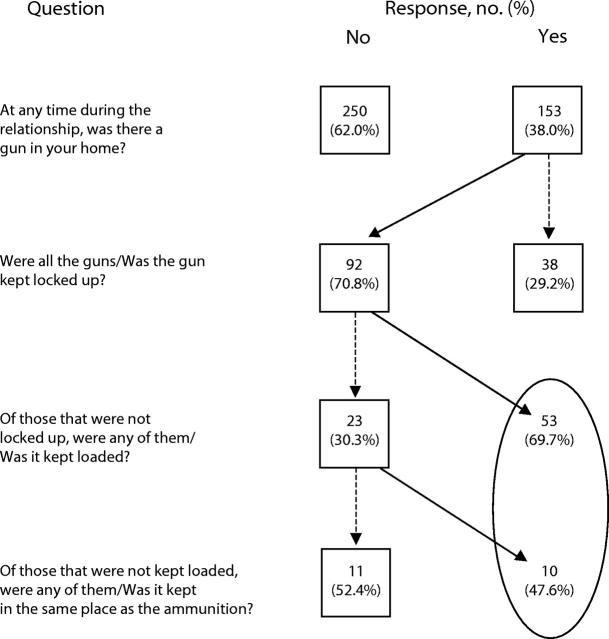

In a substantial minority of the households containing firearms, guns generally were easy to access and to fire (Figure 1 ▶). Of the 153 battered women who reported the presence of a gun or guns in the home, at least 41.2% lived where a gun was kept unlocked and loaded or unlocked and with ammunition.

FIGURE 1—

Gun-keeping practices in the homes of 417 residents of 67 California battered women’s shelters during their relationships with a violent partner.

Note. Solid arrows indicate responses leading to the observation that, among respondents reporting a gun or guns in the home, 41.2% said that at least 1 gun was kept unlocked and either already loaded or kept with ammunition. Some respondents said that they did not know how the guns were stored: 23 of 153 did not know whether the guns were locked up, 16 of 92 did not know whether the unlocked guns were kept loaded, and 2 of 23 did not know whether ammunition was kept with the unlocked and unloaded guns. These “do not know” responses were omitted from the figure.

Firearm use.

If a gun was kept in the home, the respondent was asked whether she and her partner had used the gun(s) against each other. Nearly two thirds (64.5%) responded that the partner had used one of the guns to scare, threaten, or harm her. When asked what happened during the incident, 71.4% of these 98 women reported that the partner threatened to shoot or to kill her. Respondents also reported that the partner threatened to kill himself (4.1%) or to harm or to kill the children (3.1%). Five percent (5.1%) of the women reported that their partner had shot at them (16.3% did not answer the question). In most cases (74.5%), substances had been used by the partner just before the incident: 30.6% had used alcohol and other drugs, 27.6% had used alcohol only, and 16.3% had used other drugs only.

A small proportion (6.7%) of the women reported that they had used a gun in the home against their most recent intimate partner; most often, they “scared him away/ran him off” or threatened to kill or harm him. Although few of the women had used a gun against her partner, 31.0% of those with firearms in the home said that they had thought about doing so. Among the reasons for considering using a gun, the most common ones focused on the partner—to defend against (20.8%), to kill (18.2%), to threaten or intimidate (6.5%), or to injure but not kill him (5.2%). To defend against an intruder (18.2%), to kill herself (9.1%), or to go hunting or target shooting (7.8%) were the remaining specified categories. Each of the women who used a gun against her partner reported that her partner had used a gun against her.

Perspectives on Hypothetical Options

Some countries (e.g., New Zealand) require that when a person wants to purchase a firearm or a certain kind of firearm, the opinion of the person’s spouse or intimate partner be sought. Three fourths (74.3%) of the respondents thought that this would be a good law to have, 12.7% said that it would be a bad law, 11.8% were not sure, and a few (1.2%) did not answer. Among respondents who thought that it would be a good law, more than half liked the idea because it would help to protect them from the violent partner (28.3%) or because they would then know that he had or was getting a gun (23.8%). Another 30.5% liked it because “the spouse or partner is the one who knows that person best.” The single other response category to this open-ended question was that the decision to obtain a gun should be a mutual decision (14.1%). Those opposing such a law expressed sentiments to the effect that guns should not be available at all (36.6%), while others expressed opinions such as “I don’t like guns” (7.3%) or “it’s no one’s business” and “an adult should be able to buy a gun” (4.9%). Regardless of their perspective on such a law, 91.8% of the women reported that if their opinion were sought, they would say that it was not OK for their partner to get the gun.

Personalized or “smart” guns are in development.5 Such weapons are designed so that only an authorized user (e.g., the owner of the gun) can fire them. Most respondents (67.9%) reported that having a personalized firearm in the home would make things worse for them, 11.5% reported that it would make “no difference,” 5.5% said that it would make things better, and 14.8% were unsure what effect it would have. Among those who said that a personalized firearm would make things worse, it was evaluated negatively because the woman felt that the partner could use the gun against her or the children (43.9%), because only the partner could use the gun and she could not use it for self-defense (32.2%), because she was opposed to having guns in the home (11.8%), or because any kind of gun is unsafe (9.8%).

DISCUSSION

A wide range of objects were used to injure and intimidate battered women. Although hands, fists, feet, and common household objects were the most common means of inflicting harm, the use of vehicles and firearms, 2 mechanisms with high lethality potential, were reported by more than one third of the women in this study.

Having a firearm in the home appeared to be more common in homes in which battering occurs than in households in the general population. In California, a state where more than 620 000 women experience intimate-partner violence each year,6 about 31.0% of households contain a firearm.7 Our findings suggest that among households where violence has occurred that was sufficiently chronic or severe for the woman to have sought refuge at a battered women’s shelter, the proportion of households with a gun or guns is 36.7%, or about 20% higher than in the general population. As is the case with US household gun ownership,8 the prevalence of having a gun in the home increased with education level, ranging in this study from a low of 27.8% among respondents with less than high school education to 49.7% among those who had attended or graduated from college. The proportion of households with a long gun only or with both a long gun and a handgun was lower among the households of battered women than among the general population (4.6% vs 8.9% for a long gun only; 11.3% vs 15.6% for both types of gun). However, the proportion of households with a handgun only was much higher among the women in this study than among the general population (19.9% of respondents’ households in this study vs 7.0% of households in the general population).

Study findings suggest that guns kept in a home in which there is violence are used to harm household members—specifically, an adult woman. This finding indicates 2 observations: (1) if a gun was present, its use in intimate partner violence was relatively common, and (2) the gun used against the respondent was a gun that was kept in the home. Previous research has found that keeping a gun in the home increased the risk for household members to be murdered at home; the risk for women was particularly high.9–11 However, it was not reported in that research or in related research12 whether the gun used was kept in the home.

Women who had been victimized by an intimate partner with a firearm also reported more types of weapons having been used against them during their lifetimes. Battering typically progresses from a relatively low level of violence to a level that is more frequent and severe. We cannot ascertain from these data when the firearm was first used in the course of the abuse: it may have been introduced early on and provided the tactical means by which other weapons were used against the woman or it could have been added later, after multiple other objects were used against her. We must caution that, aside from firearms use, relationship-specific weapon use was not assessed in this study; therefore, we cannot assume that the various weapons the woman reported were all used against her by the same partner, although such an assumption would seem logical. Thus, we acknowledge the possibility that a woman was in a relationship with one partner who used a firearm against her, another who used a household object against her, and so forth. Moreover, because these data share the limitations of all self-report data, we suggest that whenever possible, future research should access multiple data sources. In addition, replication of this study with other populations would be useful.

Implications for Health Care

Battered women make more visits to emergency departments than do other women13 and are at risk for numerous adverse physical, psychological, and social sequelae.14 Accurate identification of the underlying cause of patient-exhibited symptoms would likely benefit individuals’ long-term health and reduce health service use.

Even if an injury is caused by battering, the use of common household objects to inflict injury may obscure that fact. For example, a woman who participated in the focus group that was part of the questionnaire development reported that her partner used a string trimmer (an electric or gas-powered lawn/garden tool) to injure her and that in the emergency room her injuries were treated as a common household accident. Incorporating information about the incident in addition to the injury type and anatomical site would likely increase the numbers of injuries accurately attributed to battering.15

Implications for Policy

Federal and state legislation has acknowledged and attempted to mediate the link between firearms and domestic violence.16–18 As with other types of survivors or victims,19 battered and formerly battered women have been effective advocates for policy change. To our knowledge, this study is the first to seek opinions regarding firearm policies directly relevant to their circumstances from a large number of women at high risk of sustaining serious injury caused by battering. Most of the women in our study thought that smart guns would worsen their situation, whereas most favored a policy requiring spousal notification/consultation for firearm purchases.

It is important to note that battered women may be reticent to disclose violence for fear of further abuse or other consequences. Evidence of such reticence emerged in our study: when posed with a hypothetical situation in which a violent partner had applied to purchase a gun and the respondent had been asked whether the partner had been violent to her, 71.4% of respondents answered that they would have said yes if asked during the time of the relationship; this percentage rose to 87.0% when the timing of the hypothetical situation was changed to after the relationship had ended, or at least while the respondent was residing at a battered women’s shelter. Thus, although a substantial majority reported that they would have acknowledged the partner’s violence in a gun purchase situation, 13.0% said that they would not have done so even if they were in a seemingly safe place away from the partner.

Conclusions

A wide range of objects are used against and by battered women. Firearms are more common in the households of battered women and their partners than among the general population, which is cause for concern, given the lethality of firearms. In addition, firearms can be used to intimidate a woman into doing something or allowing something to be done to her—such coercion would not necessarily result in physical injury or at least not in a gunshot wound. For this reason, firearms and injury research should go beyond gunshot wounds to examine the role of threat potential in facilitating harm.

The feasibility of implementing spousal notification/consultation in the United States merits discussion, particularly in light of technological advances such as personalized weapons. If battered women’s views are more fully taken into account, unintended consequences of engineering and public policies may be foreseen and avoided.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by a grant from The California Wellness Foundation. Created in 1992 as an independent, private foundation, The California Wellness Foundation’s mission is to improve the health of the people of California by disbursing grants to health promotion, wellness education, and disease prevention programs. Research also was funded by the Public Health Foundation through a grant from the California Endowment. We thank the funders for their support.

We thank RoperASW for their work in data collection. We extend our gratitude to the executive director and staff of each of the 72 shelters that offered to participate in the study. Special appreciation goes to the 417 women who shared a part of their lives with us.

Preliminary findings from this study were presented at the 130th Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association, Philadelphia, Pa, November 9–13, 2002.

Human Participant Protection The study was approved after full review by the University of California, Los Angeles general campus institutional review board.

Contributors S. B. Sorenson conceived the study, secured the funding, designed the questionnaire, recruited shelters, supervised data collection, conducted data analysis, and drafted parts of the article and edited others. D. J. Wiebe assisted in questionnaire development and shelter recruitment, conducted data analysis, and drafted parts of the article and edited others.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice; 2000. Publication NCJ 183781.

- 2.Rand M. Violence-Related Injuries Treated in Hospital Emergency Departments: Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; 1997. Publication NCJ 156921. [PubMed]

- 3.Zimring FE. Is gun control likely to reduce violent killings? Univ Chic Law Rev. 1968;35:721–737. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaman V, Annest JL, Mercy JA, Kresnow M, Pollock DA. Lethality of firearm-related injuries in the United States population. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teret SP, DeFrancesco S, Hargarten SW, Robinson KD. Making guns safer. Issues Sci Technol. 1998;14:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund LE. Incidence of Non-Fatal Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in California, 1998–1999. Sacramento, Calif: California Dept of Health Services, Epidemiology and Prevention for Injury Control (EPIC) Branch; 2002. Report No. 4.

- 7.Smith TW, Martos L. Attitudes towards and experiences with guns: a state-level perspective. Chicago, Ill: National Opinion Research Center; 1999. Available at: http://cloud9.norc.uchicago.edu/dlib/gunst.htm. Accessed October 21, 2002.

- 8.Cook PJ, Ludwig J. Guns in America: National Survey on Private Ownership and Use of Firearms. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 1997. Publication NCJ 165476.

- 9.Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Rushforth NB, et al. Gun ownership as a risk factor for homicide in the home. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey JE, Kellermann AL, Somes GW, Banton JG, Rivara FP, Rushforth NP. Risk factors for violent death of women in the home. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:777–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiebe DJ. Firearms in the home as a risk factor for homicide and suicide: a national case-control study. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings P, Koepsell TD, Grossman DC, Savarino J, Thompson RS. The association between the purchase of a handgun and homicide or suicide. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:974–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman B, Brismar B, Nordin C. Utilisation of medical care by abused women. BMJ. 1992;305:27–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: physical, sexual, and psychological battering. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:553–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muelleman RL, Lenaghan PA, Pakieser RA. Battered women: injury locations and types. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. 18 USC §922(g)(8).

- 17.Lautenberg Amendment to the Gun Control Act of 1968. 18 USC §922(g)(9).

- 18.Domestic Violence (California’s SB218, 1999). Available at: http://info.sen.ca.gov/pub/99-00/bill/sen/sb_0201-0250/sb_218_bill_19991010_chaptered.html. Accessed October 16, 2002.

- 19.Cwikel JG. After epidemiological research: what next? Community action for health promotion. Public Health Rev. 1994;22:375–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]