Abstract

Objectives. We compared reports of deaths in which tobacco use was a contributing factor (“tobacco-associated deaths”) before and after the addition to death certificates in Texas of a check-box question asking whether tobacco use contributed to an individual’s death.

Methods. We examined Texas vital statistics files from 1987 to 1998. We calculated differences in percentages of reported tobacco-associated deaths (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) for the periods 1987 to 1992, before the addition of the check-box question, and 1993 to 1998, after the additon of the check-box.

Results. Reports of tobacco-associated deaths were significantly less frequent before addition of the check-box question (0.7%; 95% CI = 0.4%, 1.0%) than after addition of the question (13.9%; 95% CI = 13.0%, 14.7%). From 1993 to 1998, percentages of tobacco-associated deaths reported on the check-box question increased steadily.

Conclusions. The addition of a tobacco-associated-death check box on Texas death certificates significantly increased reporting of tobacco use contributions to mortality.

Tobacco use is the single most preventable cause of death and disease in the United States.1 More than 440 000 people die prematurely each year from diseases associated with the use of tobacco.2 The American Cancer Society estimates that cigarette smoking is responsible for 1 of every 5 deaths in the United States and that tobacco use increases the risk of lung and other cancers as well as the risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.1,2

In 1993, Texas became the fifth US state (preceded by Colorado, Oregon, Utah, and Washington) to add a question to its death certificate asking whether tobacco use contributed to an individual’s death. The belief in instituting this change was that information obtained from the tobacco check-box section would be more informative, useful, and interpretable to the public, clinicians, and health policymakers than estimates derived from mathematical models.3

Before implementation of the check-box question on death certificates in Texas, nosologists from the Bureau of Vital Statistics determined whether deaths were related to tobacco use using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code 305.1 (nondependent use of drugs: tobacco). Although nicotine has been widely recognized as the addicting substance in tobacco products, the ICD-9 does not classify it as a dependent drug.4

The members of a panel formed to evaluate the US standard certificate of death recently recommended that the National Center for Health Statistics include as a standard feature a specific question designed to collect information on whether tobacco use contributed to a particular death.5 The reason is that such a question would allow monitoring and documentation of the continuing impact of tobacco use on mortality and help to eliminate underreporting of such information on death certificates. The wording of the tobacco check-box question recommended by the panel evaluating the US standard certificate of death is identical to that used on the Texas death certificate.5

Data obtained from death certificates should provide the greatest possible benefit for registrars compiling health statistics, individuals engaged in medicolegal work, clinicians and other health care personnel, and epidemiologists, as well as the family of the deceased. Death certificate data represent the only continuously collected, population-based, disease-related information available in most parts of the world, including the United States.6 Although registration of deaths is virtually complete in the United States and demographic items are relatively accurate, the reliability of underlying cause of death data is hampered by several factors: lack of medical knowledge on the part of certifiers, incompleteness of information available at the time of death, lack of training on the proper completion of death certificates, and the system of classification of underlying causes.7 Several studies conducted in the United States and elsewhere have determined that underlying cause of death data often do not concur with data derived from expert panel reviews and autopsy reports.7–10

Several other remedies have been advocated to reduce inaccuracy in death certificate information and to improve the quality of underlying cause of death data reported by certifiers. These remedies include instituting continuous educational sessions and training in practical feedback mechanisms, fostering an understanding of the construction of mortality data, providing evidence-based educational interventions for death certifiers, and creating a more “user-friendly” death certificate.14–16

METHODS

We analyzed death certificate data obtained from the Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics for the period 1987 to 1998. We compared reports of deaths in which tobacco use was a contributing factor (“tobacco-associated deaths”) before and after the addition of a check-box question on state death certificates.

The term “pre-check-box period” refers to the 1987 to 1992 period, before the addition of the check box; “post-check-box period” refers to 1993 to 1998, after the addition of the check box. In the case of the pre-check-box period, we analyzed mortality data in which nosologists (using ICD-9 code 305.1) coded tobacco use as a contributing factor on the basis of information provided by individuals responsible for certifying death certificates (in Texas, physicians, medical examiners, and justices of the peace). In the case of the post-check-box period, in addition to the information just described, we used data on tobacco-associated deaths from the check-box question for purposes of comparison.

The Texas death certificate check-box question reads as follows: Did tobacco contribute to this death? The certifier has the following response options: “yes,” “probably,” “no,” and “unknown.” In analyses of the post-check-box period, deaths were classified as tobacco associated if the check-box question response was “yes” or “probably.” Percentages of tobacco-associated deaths coded by nosologists during the pre-check-box period were compared with percentages of tobacco-associated deaths in the post-check-box period in which certifiers responded “yes” or “probably” on the check-box question.

We analyzed the data using Stata software (Stata Corp, College Station, Tex). We calculated means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for percentages of reported tobacco-associated deaths before and after the addition of the check box. We calculated odds ratios using actual numbers of reports of tobacco-associated deaths. To examine variations in check-box reports of tobacco-associated deaths among sociodemographic subgroups and time trends within those subgroups, we conducted analyses stratified by gender, age (less than 35 years vs 35 years or older), race/ethnicity (White, Hispanic, African American), cause of death, and certifier (physician, medical examiner, or justice of the peace).

We also created a weighted least squares linear regression model (using the inverse of the variance estimates for weights) to determine the statistical significance of trends over time after the addition of the check-box question. A difference was considered to be statistically significant if the associated P value was below .05 or the 95% confidence intervals of the means did not overlap.

RESULTS

The overall percentage of tobacco-associated deaths reported during the pre-check-box period (0.7%; 95% CI = 0.4%, 1.0%) was significantly lower than the overall percentages of “yes” responses (9.3%; 95% CI = 8.7%, 9.9%) and “yes” and “probably” responses combined (13.9%; 95% CI = 13.0%, 14.7%) during the post-check-box period (Table 1 ▶). In the post-check-box period, 39% of deaths were classified as of “unknown” causes. Relative to reports of tobacco-associated deaths during the pre-check-box period, the odds ratio in favor of reporting such deaths in the post-check-box period was 22.79 (95% CI = 22.16, 23.44). Table 2 ▶ shows that, within each of the selected sociodemographic categories (i.e., gender, age, and race/ethnicity), mean percentages of reported tobacco-associated deaths increased dramatically after addition of the check-box question.

TABLE 1—

Comparison of Reports of Tobacco-Associated Deaths After Addition of Check Box: Texas, 1987–1992 and 1993–1998

| Certifier Check-Box Response | |||||

| Year | Total No. of Deaths | Nosologist Classification as Tobacco Related, No. (%) | “Yes,” No. (%) | “Yes + Probably,” No. (%) | “Unknown,” No. (%) |

| 1987 | 116 946 | 359 (0.3) | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| 1988 | 119 964 | 431 (0.4) | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| 1989 | 121 711 | 927 (0.8) | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| 1990 | 127 047 | 1 130 (0.9) | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| 1991 | 128 239 | 1 108 (0.9) | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| 1992 | 130 486 | 1 272 (1.0) | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Overall | 744 393 | 5 227 (0.7) | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| 1993 | 136 063 | 1 753 (1.3) | 11 356 (8.3) | 17 269 (12.7) | 56 470 (41.5) |

| 1994 | 137 604 | 1 804 (1.3) | 12 273 (8.9) | 18 333 (13.3) | 54 093 (39.3) |

| 1995 | 139 567 | 2 007 (1.4) | 13 125 (9.4) | 19 314 (13.8) | 52 323 (37.5) |

| 1996 | 141 907 | 2 177 (1.5) | 13 315 (9.4) | 19 787 (13.9) | 50 702 (35.7) |

| 1997 | 144 674 | 2 441 (1.7) | 14 128 (9.8) | 21 017 (14.5) | 49 976 (34.5) |

| 1998 | 144 599 | 2 413 (1.7) | 14 330 (9.9) | 21 488 (14.9) | 48 575 (33.6) |

| Overall | 844 414 | 12 595 (1.5) | 78 527 (9.3) | 117 208 (13.9) | 312 139 (37.0) |

TABLE 2—

Reports of Tobacco-Associated Deaths, by Selected Sociodemographic Characteristics and Causes of Death: Texas, 1987–1992 and 1993–1998

| Certifier Check-Box Response: 1993–1998 | |||

| Characteristic | 1987–1992: Nosologist Classification as Tobacco Related, Mean % (95% CI) | “Yes,” Mean % (95% CI) | “Yes + Probably,” Mean % (95% CI) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 0.81 (0.47, 1.16) | 11.40 (10.68, 12.11) | 17.46 (16.41, 18.51) |

| Female | 0.53 (0.25, 0.81) | 7.01 (6.41, 7.62) | 10.00 (9.26, 10.74) |

| Age, y | |||

| < 35 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.09) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.56) | 0.97 (0.82, 1.11) |

| ≥ 35 | 0.75 (0.41, 1.10) | 10.00 (9.40, 10.60) | 14.88 (14.12, 15.64) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.05 (0.84, 1.26) | 10.87 (10.13, 11.60) | 15.90 (14.93, 16.87) |

| Hispanic | 0.40 (0.40, 0.40) | 4.53 (4.29, 4.79) | 7.75 (7.25, 8.25) |

| African American | 0.43 (0.35, 0.50) | 6.18 (5.63, 6.74) | 10.05 (9.20, 10.89) |

| Cause of death | |||

| Malignant cancer | 37.58 (34.77, 40.39) | 40.38 (39.66, 41.10) | 38.22 (37.68, 38.78) |

| Heart disease | 8.23 (1.04, 15.43) | 20.95 (20.63, 21.27) | 23.90 (23.61, 24.19) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 35.50 (33.48, 37.52) | 22.83 (22.42, 23.25) | 18.95 (18.55, 19.35) |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

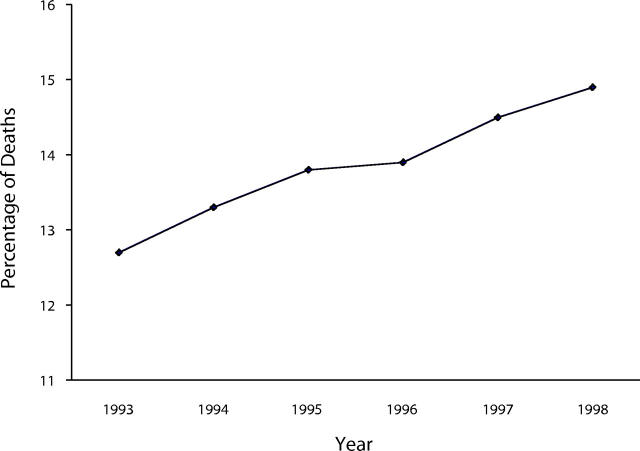

The percentage of reports indicating malignant cancer (ICD-9 codes 140–208) as the underlying cause of tobacco-associated deaths in the pre-check-box period (37.58%; 95% CI = 34.77%, 40.39%) was similar to the percentage in the post-check-box period (38.22%; 95% CI = 37.68%, 38.78%). Reports of heart disease (ICD-9 codes 390–459) as the underlying cause were significantly less frequent during the pre-check-box period (8.23%; 95% CI = 1.04%, 15.43%) than during the post-check-box period (23.90%; 95% CI = 23.61%, 24.19%). Conversely, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (ICD-9 codes 490–496) was more often reported as an underlying cause before (35.5%; 95% CI = 33.48%, 37.52%) than after (18.95%; 95% CI = 18.55%, 19.35%) addition of the tobacco check-box question (Table 2 ▶). The overall percentage of reports of tobacco-associated deaths has increased linearly over time since the addition of the check-box question (R2 = 0.98, P = .006) (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Percentages of reported tobacco-associated deaths (“yes” and “probably” check-box responses combined): Texas, 1993–1998.

Note. R = .99

Table 3 ▶ presents a comparison of reports of tobacco-associated deaths before and after the addition of the tobacco check-box question according to type of certifier. During the pre-check-box period, physicians (96.75%; 95% CI = 95.17%, 98.32%), as opposed to medical examiners (0.38%; 95% CI = 0.03%, 0.79%) and justices of the peace (2.87%; 95% CI = 1.05%, 4.69%), were primarily responsible for indicating whether tobacco use contributed to a particular death. After addition of the check-box question, this distribution did not exhibit significant changes among physicians (95.5%; 95% CI = 95.28%, 95.79%) or justices of the peace (3.20%; 95% CI = 2.96%, 3.47%); however, there was a modest increase in rates of reports on the part of medical examiners (1.30%; 95% CI = 1.07%, 1.39%).

TABLE 3—

Percentage Distribution of Types of Certifiers Responsible for Reporting Tobacco-Associated Deaths: Texas, 1987–1992 and 1993–1998

| 1987–1992 | 1993–1998 | ||||

| Type of Certifier | No. of Deaths | Distribution, % (95% CI) | No. of Deaths | Certifier Check-Box Response of “Yes”: Distribution, % (95% CI) | Certifier Check-Box Response of “Yes + Probably”: Distribution, % (95% CI) |

| Physician | 5029 | 96.75 (95.17, 98.32) | 75 929 | 96.7 (96.30, 97.10) | 95.5 (95.28, 95.79) |

| Medical examiner | 14 | 0.38 (0.03, 0.79) | 874 | 1.10 (0.95, 1.24) | 1.30 (1.07, 1.39) |

| Justice of the peace | 183 | 2.87 (1.05, 4.69) | 1 728 | 2.22 (1.87, 2.56) | 3.20 (2.96, 3.47) |

| Total | 5226 | 78 527 | |||

Note. CI = confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Reports of deaths in which tobacco use was a contributing factor increased more than 12-fold after the first year of the addition of the check-box question to the Texas death certificate, and the overall percentage of reports of such deaths has increased linearly over time. Inclusion of a simple check-box question offers certifiers a cognitive aid, encouraging them to consider whether or not tobacco use may have contributed to a particular death.

Analyses of each of the sociodemographic categories assessed here showed that, relative to nosologists’ reports during the previous 6-year period, gender-, age-, and race/ethnicity-specific reports of tobacco-associated deaths significantly increased after addition of the tobacco check-box question. However, both before and after the addition of the tobacco check-box question, most reports of tobacco-associated deaths were involved with deaths occurring among White men aged 35 years or older. In addition, most tobaccoassociated deaths continue to be reported by physicians.

Before and after the addition of the tobacco check-box question, malignant cancer was the most common diagnosis identified as an underlying cause of death. During the post-check-box period, the percentage of tobacco-associated deaths reported as diseases of the heart increased substantially, in contrast to a decline in the percentage reported as COPD. However, results of a separate analysis showed that the percentage of COPD deaths related to tobacco increased monotonically in the post-check-box period (from 52.13% in 1993 to 61.04% in 1998).

At present, the Smoking Attributable Mortality, Morbidity, and Economic Cost (SAMMEC) software distributed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is the most widely used method for determining whether tobacco is a contributing factor to a particular death. SAMMEC uses mortality data, economic cost data, smoking prevalence data, and epidemiological estimates of smoking-attributable fractions to calculate tobacco-associated deaths. In 1995, the SAMMEC estimate of the number of tobacco-associated deaths occurring in Texas was 26 247 (19% of all deaths), compared with the present results, indicating 19 314 reported tobacco-associated deaths (14% of all deaths) on the death certificate check box in addition to 52 323 (37.5% of all deaths) in which the check-box response was “unknown.”

An earlier study conducted in Oregon showed that numbers of tobacco-related deaths estimated via a death certificate check-box question identical to that used in Texas were similar to SAMMEC estimates.14 Oregon had previously had in place an active query system designed to verify questionable death certificate entries. Texas has never had such a query system; consequently, tobacco check-box reporting may not be complete. Also, the large number of “unknown” check-box responses observed in this study may have contributed to the discrepancy with the SAMMEC estimates. Our results show that reporting of tobacco-associated deaths in Texas through the use of the death certificate check box continues to improve over time, which may lead to check-box estimates of tobacco-associated deaths more closely approximating those obtained with SAMMEC. Further investigation regarding the frequency with which certifiers are responding “unknown” on the check-box question is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that overall numbers and percentages of reports of tobacco-associated deaths increased 12-fold after the addition of tobacco check boxes on Texas death certificates. Reports of deaths in which tobacco use was a contributing factor continue to increase steadily over time. Addition of a check-box question on death certificates can be a useful and practical tool for monitoring trends in tobacco-related deaths. Once such check boxes are added to the national standard, other states should move to ensure that check-box data are available for surveillance of tobacco-associated deaths.

Contributors J. C. Zevallos, P. Huang, and C. Alo contributed to the writing of the article and to analysis of the data. M. Smoot and K. Condon contributed to analysis of the data.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.The Burden of Chronic Diseases and Their Risk Factors: National and State Perspectives—2002. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002.

- 2.Cancer Facts and Figures—2001. Atlanta, Ga: American Cancer Society; 2001.

- 3.McAnulty JM, Hopkins DD, Grant-Worley JA, Baron RC, Fleming DW. A comparison of alternative systems for measuring smoking-attributable deaths in Oregon, USA. Tob Control. 1994;3:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980.

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Vital Statistics. Report of the panel to evaluate the US standard certificates. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/panelreport_acc.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2004.

- 6.Kircher T, Anderson RE. Cause of death: proper completion of the death certificate. JAMA. 1987;258:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kircher T. The autopsy and vital statistics. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zumwalt RE, Ritter MR. Incorrect death certification: an invitation to obfuscation. Postgrad Med. 1987;81:245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt LW Jr, Silverstein MD, Reed CE, O’Connell EJ, O’ Fallon WM, Yunginger JW. Accuracy of the death certificate in a population-based study of asthmatic patients. JAMA. 1993;269:1947–1952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanzlick R, Parrish RG. The failure of death certificates to record the performance of autopsies. JAMA. 1993;269:47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan JM, Bass MJ. Errors in death certificate completion in a teaching hospital. Clin Invest Med. 1993;16:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Instruction Manual Part 2a: Instructions for Classifying the Underlying Cause of Death. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1993.

- 13.Instruction Manual Part 20: Cause-of-Death Querying. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1985.

- 14.Davis BR, Curb JD, Tung B, et al. Standardized physician preparation of death certificates. Control Clin Trials. 1987;8:110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maudsley G, Williams EM. Death certification by house officers and general practitioners—practice and performance. J Public Health Med. 1993;15:192–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slater DN. Certifying the cause of death: an audit of working inaccuracies. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:232–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]