Abstract

In September 2003, the Association of Schools of Public Health administered an online survey to representatives of all 33 accredited US schools of public health. The survey assessed the extent to which the schools were offering curriculum content in the 8 areas recommended by the Institute of Medicine: communication, community-based participatory research, cultural competence, ethics, genomics, global health, informatics, and law/policy.

Findings indicated that, for the most part, schools of public health are offering content in these areas through many approaches and have incorporated various aspects of a broad-based ecological approach to public health education and training. The findings also suggested the possible need for greater content in genomics, informatics, community-based participatory research, and cultural competence.

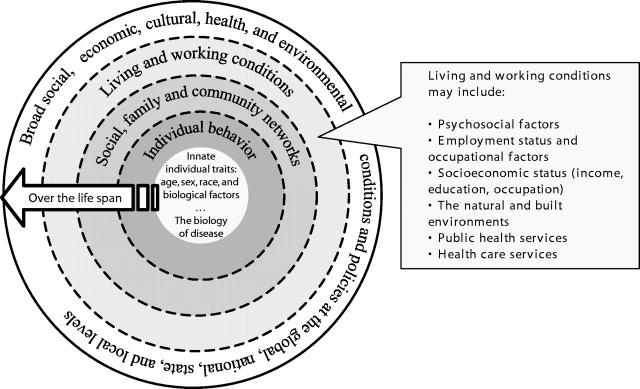

IN NOVEMBER 2002, THE Institute of Medicine (IOM) released 2 companion reports: The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century1 and Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Health Professionals for the 21st Century.2 The first report highlighted the great achievements of the past few decades in regard to improving public health in the United States but also noted that we have failed to reach our potential relative to the investments that have been made. As can be seen in Figure 1 ▶, the report, among other recommendations, advocated a broad-based ecological approach to thinking about the multiple determinants of health.

FIGURE 1—

Determinants of population health.

Source. Data are from The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century.1

The second report—Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?—also underscored the need for a broad-based ecological approach to human health and identified 8 specific content areas needed to address new challenges: communication, community-based participatory research, cultural competence, ethics, genomics, global health, informatics, and policy/law. Other recommendations involved providing access to lifelong learning opportunities for public health practitioners, encouraging greater weight for community-based participatory research in academic promotions, and enhancing faculty involvement in policy development and implementation.

As part of the mission of the Association of Schools of Public Health (ASPH) to continuously improve access to and quality of education and training in public health, the ASPH education committee undertook a survey in September 2003 designed to examine the extent to which the recommendations of Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? were being implemented and to assess future plans. The intent of the survey was to provide baseline data that could be used by the schools and other groups, such as the American Public Health Association, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Council on Education for Public Health, and the National Association of City and County Health Officers, in collaborative efforts to continuously improve the education of public health professionals.

METHODS

The ASPH education committee and staff used “Surveymon-key.com” to design the survey, collect responses, and analyze results for the purposes of establishing baseline information. The survey was completed by representatives from all 33 accredited US schools of public health. This 100% response rate obviated the need for the usual tests of statistical significance. In most cases, the associate dean for academic affairs completed the survey in consultation with division chairs or curriculum committees. In all cases, the dean of each school was asked to review responses before the information was forwarded to ASPH. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the findings derived from responses to the precoded questions, and selected open-ended narrative questions were used to provide further context, understanding, and new information in the areas of interest.

On the basis of the IOM report, the following definitions were used for each of the recommended content areas. Communication was defined as translation of science and messages about the attitudes and behaviors the public should adopt and the resulting policies that organizations and the government should enact to support population health. Community-based participatory research was defined as a collaborative, partnership approach to public health research that equitably involves community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process. Cultural competence was defined as cultural awareness evidenced by public health professionals in terms of their knowledge of themselves and others along with their communication skills, attitudes, and behaviors.

Ethics was defined as values or standards designed to shed light on the relative “rightness” or “wrongness” of actions based on moral principles endorsed or practiced by public health professionals. Genomics was defined as study of the actions of single genes and the interactions of multiple genes with each other and with the environment. Global health was defined as a cross-national approach to public health that includes the study of global issues and their determinants, an understanding of how local actions can have health effects across the globe, and interactions with individuals from other countries to solve trans-border problems. Informatics was defined as systematic application of information, computer science, and technology to public health practice and learning.

Public health policy development was defined as service in the public interest with the goal of comprehensive public health outcomes. This is accomplished by promoting the use of scientifically based decisionmaking and by leading in developing public health policy. Law is described as an essential component of training in policy, and because laws are used as structural interventions to regulate individual behavior and to change social and material conditions that endanger health, laws are also an important tool for intervention and public health. Although treated as a single content area in the IOM report, the ASPH committee believed that public health policy and law merited separate treatment in considering curriculum content.

Additional or alternative definitions could be developed for each area, but the definitions just described were those used in the IOM report.

RESULTS

Overall Findings

Seventy percent of the respondents reported that their schools were implementing specific changes in response to the IOM report. The most frequently reported change (mentioned by 36% of the respondents) involved appointing a committee or task force to review the report’s recommendations. At the same time, most respondents indicated that their schools were already offering much of the content identified in the 8 areas.

Nearly all of the respondents (97%) reported plans for further implementation over the coming year. One school is planning a school-wide faculty retreat “to discuss the implications for research initiatives from the IOM report. We convened a school-wide committee to examine our core curriculum. That committee has just recommended to the school that we . . . create an integrated core course . . . structured around the ecological model and develop modules and case studies relevant to the new content areas.” According to another respondent, “this survey . . . was a more powerful stimulus for reflection and discussion than the initial release of the report.”

The respondent representing a third school indicated that “we plan to institute changes that would be consistent with the report, not because of it.” Still another noted that “we are considering some curriculum changes where some of the competency area[s] proposed in the IOM report are touched upon. We do not plan or support any curriculum changes which would change the core requirements for accreditation.”

Nearly all of the schools (94%) have incorporated the ecological approach into one or more aspects of their activities, most notably in selected lectures and modules in elective courses (66.7%) or required courses (64%). Nearly half of the schools (49%) have also appointed task forces or committees to further examine the implications of the ecological approach in regard to teaching, research, and service activities.

In regard to lifelong learning opportunities, 79% of the respondents reported that their schools had a specific strategy for their own graduates, and 88% reported such a strategy for other health care professionals. Examples included certificate programs (66.7%), formal degrees (75.8%), and continuing education courses and conferences (84.8%).

Ninety-seven percent of the respondents reported that faculty members in their schools were extensively involved in translating the results of their research for policy and practice or directly involved in policy and practice itself. Seventy-five percent of the respondents reported that their school’s faculty received academic recognition and rewards for involvement in such activities.

Forty-eight percent of the respondents reported that their schools assigned “high priority” to community-based participatory research for purposes of academic promotion and merit review, while 39% reported that this area was assigned “medium priority.” Nearly all of the respondents (97%) reported that their schools provided students with opportunities for training in community-based public health.

Specific Content Areas

Table 1 ▶ summarizes curriculum offerings and plans in each of the recommended content areas. As can be seen, the majority of respondents reported that their schools offered content in communication (82%), cultural competence (58%), ethics (85%), global health (79%), law (88%), and policy (94%). In addition, more than 80% of the respondents reported that their schools offered communication, ethics, law, and policy content in the form of an entire course, and 79% reported that their schools offered global health as an entire course. Of these content areas, policy, ethics, and communication were most likely to be required in the core curriculum.

TABLE 1—

School of Public Health Offerings in Content Areas Recommended by the Institute of Medicine

| Type, %a | ||||||

| Content | Course | Lecture/Module | Required as Part of Core, % | Elective,% | Area of Specialization/Concentration, % | Future Plans to Add, % |

| Communication | 82 | 76 | 58 | 94 | 30 | 73 |

| Community-based participatory research | 48 | 67 | 36 | 91 | 15 | 76 |

| Cultural competence | 58 | 79 | 48 | 97 | 12 | 64 |

| Ethics | 85 | 70 | 61 | 94 | 12 | 79 |

| Genomics | 52 | 58 | 15 | 76 | 30 | 70 |

| Global health | 79 | 70 | 18 | 94 | 61 | 76 |

| Informatics | 64 | 58 | 30 | 97 | 33 | 79 |

| Law | 88 | 58 | 33 | 97 | 24 | 52 |

| Policy | 94 | 73 | 79 | 100 | 79 | 73 |

Note. Responses were received from 33 accredited schools, a response rate of 100%. aIn addition, all schools offered some amount of content in each area through one or more of the following forums: continuing education courses, conferences, symposiums, seminars, and related activities.

A somewhat lower percentage of schools were offering content in the areas of community-based participatory research, genomics, and informatics; even here, however, more than half of the schools were offering content in these areas either in the form of an entire course or in lectures and modules. With the exception of genomics, more than 90% of the schools were offering students content in an elective course; the figure for genomics was 76%. Policy (79%) and global health (61%) were the most frequently mentioned areas in which schools offered specializations or concentrations. At least 70% of the schools were planning to add content in all of the areas except law (52%) and cultural competence (64%).

We also examined the data according to school type (public [n = 23] vs private [n = 10]) and size (60 or more full-time equivalent faculty members [range: 61 to 205] vs fewer than 60 full-time equivalent faculty members [range: 16 to 56]). There were no differences by size in regard to any of the recommended content areas required as part of the core. Larger schools, however, were more likely than smaller schools to provide genomics, global health, policy, and ethics as an area of specialization or concentration. This finding may reflect the greater number of faculty and resources available in these schools. With the exception of genomics, there were no differences by size in regard to schools’ plans to add more content. Larger schools were more likely than smaller schools to have plans to expand content in genomics.

New Content Areas and Related Issues

Respondents were asked to suggest additional content areas. Among the areas that were mentioned by at least 2 respondents were leadership and advocacy training, aging, emergency preparedness and risk communication, health disparities, and mental health/violence/substance abuse.

Several respondents commented more generically on the importance of flexibility and the need for more of a focus on the development of certain core competencies. One respondent noted: “The MPH curriculum should not become a series of content-based courses. . . . Rather, the response should be the development of core competencies for all MPH students that identify both the skills and content needed for entry into practice.” According to another respondent:

Public Health, broadly conceived, is an area of professional activity where the knowledge, skills, abilities, attitudes and values are continually and rapidly evolving as needs and priorities change. Because of this, it is shortsighted, and perhaps dangerous, to think in terms of content areas when planning for the initial education and continuing education of practicing professionals. Alternatively, it would be wiser to think in terms of areas of competence as constant over time, with the content required for development of the competence changing as knowledge and priorities for action change.

DISCUSSION

The present findings indicate that the majority of schools of public health have been offering content in the IOM-recommended areas and are planning to expand content in these areas in the immediate future. These baseline results paint a generally encouraging picture of the schools’ responsiveness to the new public health challenges and to the needs of the field. However, the data also suggest the need for greater content in genomics, informatics, community-based participatory research, and cultural competence. In particular, the combination of continued biomedical advances in genetic and genomic research and information technology is likely to have a profound effect on public health practice and the health delivery system at large.

In turn, the ability of communities, broadly defined, to understand and incorporate such advances will be challenged, thus calling for a greater emphasis on community-based participatory research and on providing graduates with increased skills in the area of cultural competence. A cross-cutting area identified was the need for greater skills and knowledge in regard to leadership and advocacy.

Our data reflect differences in school missions, resources, student composition, and communities served. These differences underscore the importance of flexible approaches to incorporating advances in public health knowledge, curriculum design and implementation, and practice.

The ecological approach to human health adopted by most schools of public health may serve as a framework for the future evolution of the field in terms of both academia and practice. Its advantage is that it provides a coherent, systemic method of examining relationships among content areas and, thus, moving beyond a simple listing of courses or content areas. The present findings also indicate that schools of public health are strongly committed to a lifelong learning approach that involves working in collaboration with others, encouraging widespread faculty involvement in policy activities at all levels, and assigning community-based participatory research a medium to high degree of priority in faculty promotion and review decisions.

The data and findings described here represent a baseline or benchmark for purposes of assessing changes over time. The results reflect an overall assessment of curriculum content. Further work is needed to determine the actual number and percentage of students who receive content of varying degrees. It is certainly possible that a number of students graduating with an MPH degree from one or more schools may receive no content at all in informatics, genomics, or other areas even though such content is offered as an entire elective course or as a series of lectures in various courses.

Finally, our survey did not address the actual depth or detail of content offered in each of the areas. However, the present findings can be used as a starting point for encouraging informed dialogue among all stakeholders interested in improving knowledge and practice in the field of public health. Periodic reassessments will provide an indication of the extent to which and the speed with which the schools and their partner organizations are progressing in the areas highlighted in the IOM report and will help identify better practices that can be more widely implemented.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement U36-CCU-300430-22).

We acknowledge the helpful input and comments of the education committee working group members: Ann Anderson, Mark Becker, Cathleen Connell, Jim Curran, Meryl Karol, Kerry Kilpatrick, Ian Lapp, Bob Meenan, Kathy Miner, Linda Rosenstock, Pat Wahl, James Ware, and Jim Yager. We also acknowledge the support of Palmer Beasley, chair of the Association of Schools of Public Health, and Harrison Spencer, president and CEO of the Association of Schools of Public Health.

Note. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributors S. M. Shortell conceived the study, supervised its implementation, and developed the article. E. M. Weist coordinated the study and resulting article. M. K. Sow assisted with the study, developed and analyzed the data, and assisted with the editing of the article. A. Foster and R. Tahir assisted with the study and contributed to analyzing the data.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century, Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002.

- 2.Committee on Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century, Institute of Medicine. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed]