Abstract

The primary health care approach was introduced to the World Health Organization (WHO) Executive Board in January 1975. In this article, I describe the changes that occurred within WHO leading up to the executive board meeting that made it possible for such a radical approach to health services to emerge when it did. I also describe the lesser-known developments that were taking place in the Christian Medical Commission at the same time, developments that greatly enhanced the case for primary health care within WHO and its subsequent support by nongovernmental organizations concerned with community health.

Figure 1.

Health promoters at the bedside of a sick child, Chimaltenango Hospital.

THE PERIOD 1968 TO 1975 saw dramatic changes in the priorities that governed the work program of the World Health Organization (WHO). For more than a decade, the global malaria eradication campaign had been WHO’s leading program. Initiated in the mid-1950s, it was a strictly vertical program based on the insecticidal power of DDT. Only in the early 1960s was it acknowledged that a health infrastructure was a prerequisite for the success of the program, especially in Africa.

Independent of the malaria campaign’s needs, UNICEF, wishing to increase available funding to help governments develop health services, sought technical guidance from WHO for planning such services. In response, WHO prepared in 1964 a short paper outlining broad principles for the development of basic health services. The model, which followed an outline developed in the early 1950s,1 called for a hierarchical arrangement of health facilities staffed by a wide range of public health disciplines.

As it became evident that malaria eradication would not be achieved, greater priority was given to the development of basic health services. The then-director general of WHO, Dr Marcolino Candau, in 1967 noted that “the success of practically all the Organization’s activities depends upon the effectiveness of these very services.”2 In 1968, Candau again highlighted their importance and called for a comprehensive health plan, within which an integrated approach to preventive and curative services could be developed.3

I begin this article with a description of 2 WHO programs, one initiated in 1967 and the other in 1969, that became deeply involved in questions concerning what countries should do to improve their health services. I then turn to the history of the Christian Medical Commission (CMC), which was addressing similar questions, but for totally different reasons.

The parallel paths of WHO and the CMC came together only after Dr Halfdan T. Mahler became director general of WHO in July 1973. I conclude the article by describing how cooperation between these 2 organizations developed and how it influenced the formulation of the primary health care approach.

WHO—SEEDS OF CHANGE

In 1967, a new division was created in WHO: Research in Epidemiology and Communications Science. Its director, Dr Kenneth N. Newell, was an infectious disease epidemiologist. Among the research projects developed, one addressed research in the organization and strategy of health services. Its purpose was “the development and demonstration of methods to show that a rational approach to the formulation of health strategies is desirable, possible and effective.”4 By “rational approach” was meant the incorporation of epidemiological, ecological, and behavioral perspectives into the health services planning process, while “methods” included standard statistical methods plus mathematical and simulation modeling; these were part of the “systems analysis” approach that was very much in vogue at the time.

In 1969, a new program called Project Systems Analysis was established in WHO. Its director, Dr Halfdan T. Mahler, a tuberculosis specialist, had been chief of the Tuberculosis Unit from 1962 to 1969. Although both programs had many points in common, Mahler’s program was created as an instrument to change the way WHO worked with countries, an orientation that was outside Newell’s mandate.

Candau appointed Mahler assistant director general in September 1970, assigning him responsibility for both programs as well as the divisions concerned with health care (Organization of Health Services and Health Manpower Development). He was 1 of 5 assistant director generals who shared responsibility for around 15 technical programs. Although the programs worked for common goals, each pursued their objectives following somewhat independent paths, thereby contributing to a highly fragmented situation that Mahler’s program hoped to overcome through improved project and program planning methodologies.

In January 1971, the executive board chose the subject of methods of promoting the development of basic health services for its next organizational study.5 To facilitate this study, the WHO secretariat prepared a background document for the board’s deliberations in January 1972. It provided an excellent historical overview of the subject and identified different ways that WHO might assist countries—for example, “organize a planning and evaluation section in their ministry of health,” “train health planners in the establishment and implementation of national training programmes,” and “prepare plans for the organization and development of the public health services.”6 No reference was made to community participation.

In introducing this document, Mahler noted that “there were sufficient financial and intellectual resources available in the world to meet the basic health aspirations of all peoples,” and suggested that “there was a need for an aggressive plan for worldwide action to improve this unsatisfactory situation.”7

In 1972, Mahler oversaw the amalgamation of Newell’s research division with the Organization of Health Services to create a new division, Strengthening of Health Services, with Newell as director. Newell inherited the job of secretary to the executive board’s working group responsible for the organizational study. He worked closely with its members and was deeply involved in drafting the group’s final report on basic health services, which was presented to the full executive board in January 1973.

Avoiding the question of what was meant by basic health services, the working group identified the criteria whereby national health services should be judged and the role that WHO might play in assisting member states to improve their health delivery systems. These criteria were as follows: health status, in terms that included “fertility, the opportunity for proper growth and development, morbidity, disability and mortality”; operational factors, such as coverage and use of health service facilities; accepted technology; cost; and consumer approval.8

The report concluded that no single or best pattern existed for developing a health services structure capable of providing wide coverage and meeting the varying needs of the population being served: “Each country will have to possess the national ability to consider its own position (problems and resources), assess the alternatives available to it, decide upon its resource allocation and priorities, and implement its own decisions.”9

WHO, the report said, should serve as a “world health conscience,” thereby providing a forum where new ideas could be discussed as well as a “mechanism which can point to directions in which Member States should go.”10 To fulfill this role, WHO needed to make better use of the resources available to it by concentrating on those projects that were likely to “show major returns and...result in a long-term national capability for dealing with primary problems.”11

In May 1973, the 26th World Health Assembly adopted resolution WHA26.35, entitled “Organizational Study on Methods of Promoting the Development of Basic Health Services.” Among other things, this resolution confirmed the high priority to be given to the development of health services that were “both accessible and acceptable to the total population, suited to its needs and to the socioeconomic conditions of the country, and at the level of health technology considered necessary to meet the problems of that country at a given time.”12 This wording reflects the impact of the executive board’s study. Countries were again being reminded that there was no universal model for the health services that they could or should aim to develop. They had to adapt available technologies to fit the conditions that were unique to each situation. The assembly also confirmed the election of Mahler as the next director general of WHO, the functions of which he assumed on July 21, 1973.

Shortly after Mahler became director general, a WHO/UNICEF intersecretariat discussion decided to seek out “promising approaches to meeting basic health needs”; among possible characteristics to be considered were “community involvement in financing and controlling health services, in projects to solve local health problems, in health-related development work, or other relevant ways.”13

The search for new approaches led to 2 important WHO publications in early 1975: Alternative Approaches to Meeting Basic Health Needs of Populations in Developing Countries, edited by V. Djukanovic and E. P. Mach (staff members under Newell), and Health by the People, edited by Newell.14 During the first 18 months that Mahler was director general, the WHO and the CMC greatly intensified their cooperation. It is therefore necessary to backtrack and learn how the CMC came into being and how its activities became so important for WHO in the years that followed.

ESTABLISHMENT AND EARLY WORK PROGRAM OF THE CMC

The CMC was established in 1968 as a semiautonomous body to assist the World Council of Churches in its evaluation of and assistance with church-related medical programs in the developing world. The decision to create the CMC did not take place overnight. It evolved from much field work and a series of consultations. The field work, which started in late 1963, showed that churches had concentrated on hospital and curative services and that these “had a limited impact” in meeting the health needs of the people they were meant to be serving. It was found that “95% of church-related work was curative” and “at least half of the hospital admissions were for preventable conditions![sic]”15

Of particular concern to the World Council of Churches was the fact that many of the more than 1200 hospitals that were run by affiliated associations were rapidly becoming obsolete and their operating costs were increasing dramatically. What was needed were “some criteria for evaluating these programmes” that would help reorient the direction for their future development.16

The CMC had very limited resources. It was composed of 25 members and was served by an executive staff consisting of a director and “not more than three others.”17 It was to engage in surveys, data collection, and “research into the most appropriate ways of delivering health services which could be relevant to local needs and the mission and resources of the Church.” It was concerned with determining “what specific or unique contribution to health and medical services can be offered by the Church.”18

Two major consultations, called Tübingen I (May 1964) and Tübingen II (September 1967) had set the stage for the work of the CMC. Tübingen I reviewed the nature of the church’s involvement in healing and the theological roots of such work. In contrast to the response of medical missions in the early part of the 19th century to the overwhelming need at that time, which was “instinctive without any conscious concern about its theological justification,” the justification for current activities, both medically and theologically, was still weakly developed.19 The church’s medical staff was trained in medical care and had little interest in disease prevention, which was considered to be the government’s responsibility.

The report resulting from Tübingen I, The Healing Church, confirmed that the church did have a specific task in the field of healing. The medicalization of the healing art had led to a rift between the work of “those with specialized medical training and the life of the congregation.” The entire congregation had a part to play in healing.20

James C. McGilvray, the CMC’s first director, found the contribution of Dr Robert A. Lambourne to be “the most significant” one in the preparatory stages of Tübingen II. McGilvray had been involved in hospital and health services administration since 1940, first when he was superintendent of the Vellore Medical College Hospital in India and then in various health administration positions in Southeast Asia and the United States.

From Lambourne’s reports, a disturbing picture emerged of the manner in which modern care was at odds with the quest for health and wholeness. The hospital had become a “factory for repair,” in which the patient had been broken down into “pathological parts.” The “results of a battery of tests” were more important “than the relationship of persons in a therapeutic encounter.”21

Lambourne’s concept of wholeness and health had strong implications for the congregation, a position that had emerged from Tübingen I. It is only “when the Christian community serves the sick person in its midst [that] it becomes itself healed and whole.”22 Going further, he argued that the healing congregation accepts the fact “that any one individual group or nation may not be entitled to an unlimited use of the resources of healing when such unlimited use will mean less available resources of healing for others.”23 Thus, Lambourne’s argument suggested a moral basis for individuals and communities to be involved in any consideration of how resources are to be used to promote their health.

The theological basis for health and healing work continued as important points of discussion during the CMC’s first annual meetings. These were critical in helping the commission advise the World Council of Churches how to help church-funded services to move from the provision of medical care to individuals to the development of curative and preventive services to communities at large.

The discussions took the form of a “dialogue” between Dr John H. Bryant, the commission’s chairman and a professor of public health, and David E. Jenkins, a commission member and a theologian. The last dialogue, which took place in 1973, demonstrates well to what degree, even though there were important differences of opinion between them, both were committed to a distribution of resources that improved the lot of those worst off.

Bryant addressed the question of “health care and justice.”24 In doing so, he applied the notions of entitlement, natural rights, positive rights, and distributive justice to the question of human health, and developed a series of tentative principles:

Whatever health care and health services are available should be equally available to all. Departure from that equality of distribution is permissible only if those worst off are made better off.

There should be a floor or minimum of health services for all.

Resources above this floor should be distributed according to need.

In those instances in which health care resources are nondivisible or necessarily uneven, their distribution should be of advantage to the least favored.25

Jenkins approached the question differently. He did not believe, for example, that “the notion of human rights is biblical.” The Bible is concerned about “human possibilities, about divine activities, and about human response to divine activities,” and with “obstacles to becoming human,” and consequently is much more concerned with “attacking exploitations, attacking oppressions, attacking inequalities, attacking deprivation than laying down rights.”26

The reflections of both Bryant and Jenkins supported the involvement of Christians in fighting inequities. To do so, the CMC from its inception gave priority to what it termed comprehensive health care—“a planned effort for delivering health and medical care attempting to meet as many of the defined needs as possible with available resources and according to carefully established priorities.” Such a program “should not be developed in isolation but as the health dimension of general development of the whole society.”27

Given the fragmented and often competing nature of most church-related programs, the CMC identified planning as “the most important new dimension in the field of health care today” as a means of exercising “stewardship with their resources.” Stewardship was required “not only to achieve the optimum health care within our resources, but equally to see that the results are economically viable in the local context.”28

CMC staff actively worked with various church groups and voluntary organizations to encourage them to undertake joint planning and action with the aim of promoting a more effective use of resources. At the same time, they searched for field situations that lent themselves “to experimentation in broad-based community health programmes.”29 Along with members of the commission, they also searched for community-based experiences around the world that would shed light on how best to develop programs that were comprehensive (i.e., would offer a spectrum of services ranging from treatment and rehabilitation to prevention and health promotion), were part of a network of services ranging from the home to specialized institutions, and would incorporate human resources ranging from involved church members to specialist professionals, including auxiliary and midlevel health workers.30

Many of the community-based experiences uncovered were discussed at various CMC meetings and were written up in the publication Contact, whose first issue appeared in November 1970.

Contact was not a regular publication. For the first few years, around 6 issues were published annually. The first issue was a summary of a lecture given by Lambourne entitled “Secular and Christian Models of Health and Salvation.” Issue 4, published in July 1971, contained the Bryant–Jenkins dialogue held during the third annual meeting in June of that year.

Three community-based experiences presented to the CMC between 1971 and 1973 proved critical in WHO’s conceptualization of primary health care.

CRITICAL COMMUNITY-BASED EXPERIENCES

McGilvray “discovered” the first project during a survey undertaken in Indonesia in 1967.31 The project, located in central Java, was run by Dr Gunawan Nugroho. Begun in 1963, it featured such innovations as goat and chicken farming to increase the income available to the poorest members of the community and the creation of a health fund that aimed at “providing inexpensive treatment so that anyone who was sick could afford to seek medical care.”32 Educational activities were stressed to provide individuals with the information they needed to learn for themselves what they could do to improve their health and that of the community.

Although Nugroho presented his project to the CMC’s annual meeting in 1971, and Newell had met him in the early 1960s when he was working in Indonesia, Newell only learned about Nugroho’s project in late 1973. Dr Joe Wray, who was then with the Rockefeller Foundation in Bangkok, ran into Newell in the “middle of nowhere” in India and told him about the project when he learned that Newell was looking for “people who were doing interesting things in rural health care.”33 Subsequently, Newell visited Nugroho and invited him to Geneva in July 1974 to prepare a chapter on his project for Health by the People.34

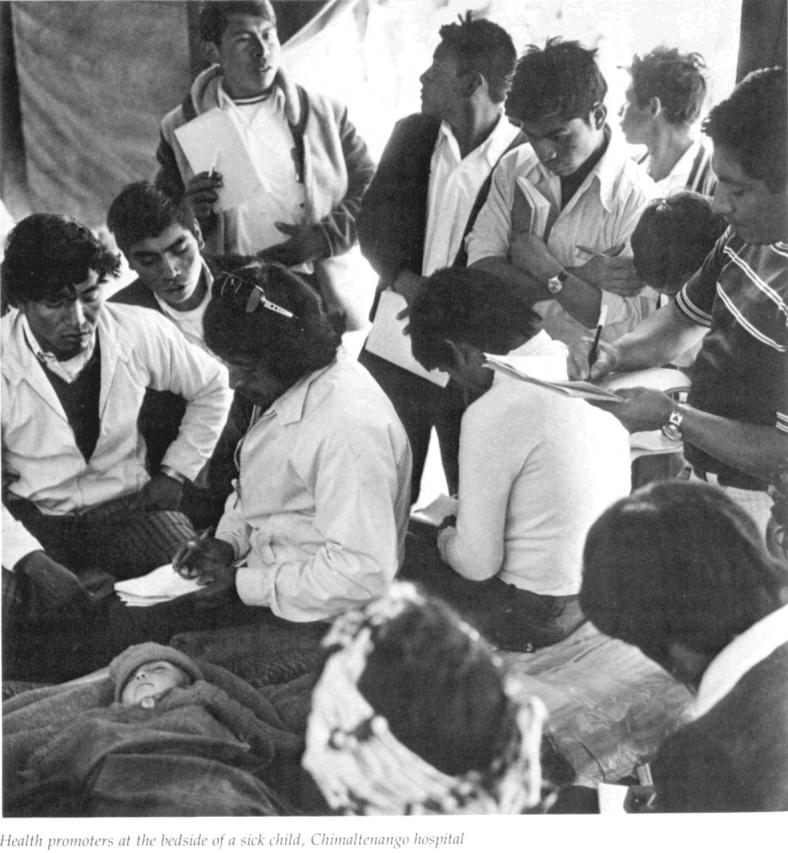

The second project was also run by a husband–wife medical team, Rajanikant and Maybelle Arole. Their project was developed in Jamkhed, India. The Aroles sought financial help from the CMC in 1970, at which time they described how their initial attempts at providing curative services “had done little for the general health of the community around us.”35

When on their return they found the project area facing a severe drought, they helped organize a community kitchen and found funding for introducing tractors in areas where farmers had lost their cows and for installing deep tube wells. To extend services to nearby villages, they contacted indigenous practitioners and health workers in the area, helping to shape them into health teams and to extend the services offered by introducing village health workers.

The Jamkhed project aimed to establish a viable and effective health care system that involved the “community in decisionmaking,” was “planned at grass roots,” used local resources “to solve local health problems,” and provided “total health care not fragmented care.”36

Rajanikant Arole presented their project to the 1972 annual meeting of the CMC, and it was written up in Contact. The WHO regional office in New Delhi had not recommended this project because “it wasn’t an Indian government project.” However, it came to the attention of Dr Ed Brown, who was working for Djukanovic (the WHO officer responsible for the alternative approaches study) while on sabbatical leave from the Indiana University Medical Center. Brown gathered the project files from the CMC (which was just down the road from the WHO office) to show Djukanovic, who then visited the project and made arrangements for its inclusion in his study.37

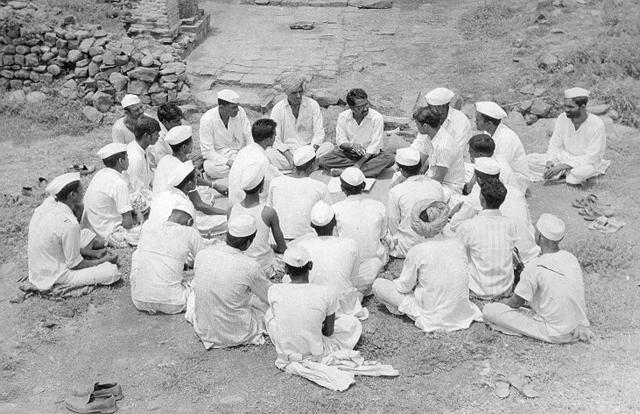

In the third critical community-based experience, Carroll Behrhorst directed the Chimaltenango development project in Guatemala. The use of community health promoters was one of the major features of this project. Initially selected on the basis of recommendations from local priests or Peace Corps volunteers, this approach quickly gave way to the formation of community health committees who took over this responsibility.

Figure 2.

Thanks to a mini-dam built by the community with village labor and the help of a small loan from the health center, Sirkandi village in central Java, Indonesia, increased its rice production by 25% in 1 year.

Source. Gunwan Nugroho.

The training of community health promoters was a continuous activity. They were trained in groups, attending sessions once weekly for a year before they were allowed to dispense medicines or give injections. They could enter the program at any time; “nearly all of them, even those who began their training more than 8 years ago, still come every week to learn new techniques or treatments.”38

Promoters were also trained as community catalysts, working in areas other than curative medicine (e.g., literacy programs; family planning; the organization of men’s and women’s clubs; agricultural extension; the introduction of new fertilizers, new crops, and better seeds; chicken projects; and improving animal husbandry).39

Figure 3.

A farmers’ club gathering in Jamkhed, India.

Source. Connie Gates.

Behrhorst presented his project at the CMC’s 1973 annual meeting, and it was written up in Contact the following year.40

There is no doubt that other experiences, either then ongoing or publicized earlier, had an influence on Newell’s conceptualization of primary health care. As an active member of the UK social medicine community in the 1950s, he would have been exposed to related concepts and projects early in his career. He was a contemporary of John Cassel, whom Newell knew well and admired; Cassel frequently visited Geneva, where he presented his latest social epidemiological research results. These were actively followed and discussed by the epidemiologists working in Newell’s research division.

Cassel’s early career was “closely intertwined with [Sidney] Kark’s.”41 It is therefore highly probable that it was he who introduced Newell to Kark, who was Newell’s dinner guest on at least one occasion before 1973.42 Given Newell’s interest in social medicine and epidemiology, it is difficult to imagine that he did not learn, first from Cassel and then from Kark, of their earlier community-oriented primary care experience in South Africa.43 Many similarities between primary health care and Kark’s work in Africa are evident.

WHO AND CMC JOIN FORCES

By the summer of 1973, the CMC had brought to the world’s attention many projects that offered innovative ways to improve the health of populations in developing countries. WHO, under its new leadership, intensified efforts to seek alternative approaches to meeting the basic needs of those same populations. New leadership was required to bring about a closer working relationship between the CMC and WHO.44 “In the Candau-Dorolle era [of WHO] there was a basically hesitant if not negative relation to religious bodies,” said Dr Hakan Hellberg of the CMC, speculating that WHO might have felt pressure from the Catholic Church on sexual issues.45 Even before taking over as director general from Candau, Mahler was advising WHO staff to read the February 1973 issue of Contact (issue 13), which was on rural health.46

The first official sign of efforts to bring WHO staff together with CMC staff was a letter from McGilvray to the commission members. Dated November 7, 1973, it said that Dr Tom Lambo, the new deputy director general of WHO, “is arranging a meeting between our staff and several officers of that organization to explore more effective ways of working together.” That meeting did not take place until March 22, 1974, at which time the small professional staff of the CMC met with some 10 senior WHO staff, including Newell. Newell reacted enthusiastically to the discussion that took place.47 To what degree he was already aware of the CMC before the meeting is not easy to judge. His father had been a minister who worked for the World Council of Churches in Geneva in the late 1940s or early 1950s, suggesting that he might have had an even deeper knowledge of their health-related activities than those who worked with him realized at the time.48 In any case, he seized the opportunity offered to work with individuals who clearly shared his values concerning human and health development.

Immediately after this meeting, Newell met with McGilvray and Nita Barrow, deputy director of the CMC, to decide on how to explore “possible collaboration and the mechanisms of action.”49 A joint working group was established, with Barrow and Newell designated as representatives from the CMC and WHO, respectively. The working group prepared a 6-page statement that was subsequently approved by both organizations.50

It was envisaged that a working relationship could best be achieved by “joint involvement in common endeavours” in the domain of “policy and research, or research and development endeavours with particular emphasis upon health delivery systems at the peripheral level.”51

Newell attended the CMC annual meeting in July 1974, where the joint statement was discussed. Following the meeting, McGilvray wrote Mahler that it was “enthusiastically welcomed by our membership.”52 In his annual report, McGilvray noted that “cooperation has already begun at a very practical level.” Referring to the inclusion of the 3 projects discussed earlier in the reports being prepared by WHO, he expressed his delight “by this development, not so much because of the credibility it confers upon us, as because it significantly enhances our mutual efforts to ensure health services for those who are now deprived of them.”53

The 3 community-based projects were incorporated into Newell’s Health by the People, a publication that he viewed as “an extension” of the alternative approaches study.54 Only the Jamkhed project had been included in the publication edited by Djukanovic and Mach.

Newell classified the case studies from China, Cuba, and Tanzania included in Health by the People as examples of changes introduced at the national level, while those from Iran, Niger, and Venezuela represented examples of changes introduced through an extension of services provided by the existing health services system. He classified the 3 community-based experiences discussed in the previous section as local community development. Each example offered something different—China, for example, trained large numbers of part-time health workers (barefoot doctors), while Venezuela introduced what it called “simplified medicine” and Tanzania mobilized its rural population into “Ujamaa villages” that that were socialistic in structure and designed to encourage popular participation in development planning.

While Newell expressed excitement at what had been demonstrated in all of the programs, he was particularly enthusiastic about the 3 community development projects. He contrasted issues such as improving the productivity of resources to enable people to eat and be educated—and the sense of community responsibility, pride, and dignity obtained by such action—with the more traditional public health activities of malaria control and the provision of water supplies. The challenge for people in the health field was to accept these wider developmental goals as legitimate ones for them to pursue; Newell even said that “without them there must be failure.”55

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE: WHO’S NEW APPROACH TO HEALTH DEVELOPMENT

Resolution WHA27.44, adopted by the 27th World Health Assembly in July 1974, called on WHO to report to the 55th session of the Executive Board in January 1975 on steps undertaken by WHO “to assist governments to direct their health service programmes toward their major health objectives, with priority being given to the rapid and effective development of the health delivery system.”56 This provided Mahler and Newell with the opportunity to introduce primary health care in a comprehensive manner, drawing on the work of the previous 2 years.

Figure 4.

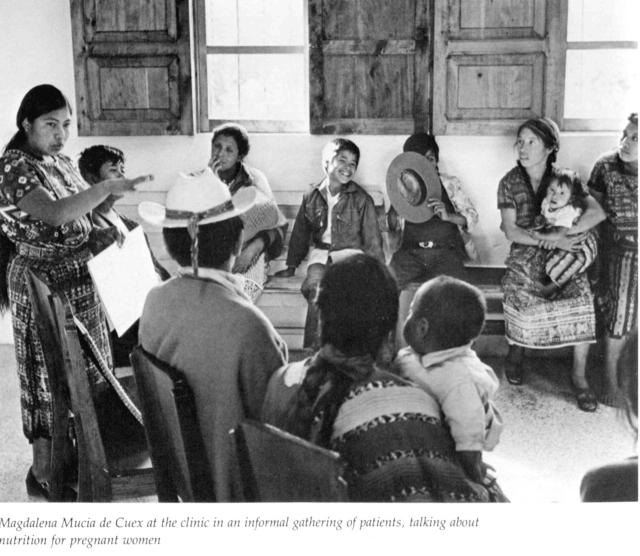

Magdalena Mucia de Cuex at the clinic in an informal gathering of patients, talking about nutrition for pregnant women.

The paper presented to the board, known as document EB55/9, argued that the “resources available to the community” needed to be brought into harmony with “the resources available to the health services.” For this to happen, “a radical departure from conventional health services approach is required,” one that builds new services “out of a series of peripheral structures that are designed for the context they are to serve.” Such design efforts should (1) shape primary health care “around the life patterns of the population”; (2) involve the local population; (3) place a “maximum reliance on available community resources” while remaining within cost limitations; (4) provide for an “integrated approach of preventive, curative and promotive services for both the community and the individual”; (5) provide for all interventions to be undertaken “at the most peripheral practicable level of the health services by the worker most simply trained for this activity”; (6) provide for other echelons of services to be designed in support of the needs of the peripheral level; and (7) be “fully integrated with the services of the other sectors involved in community development.”57

Four general courses of national action were outlined, with the expectation that each country would respond to its need in a unique manner:

1. the development of a new tier of primary health care;

2. the rapid expansion of existing health services, with priority being given to primary health care;

3. the reorientation of existing health services so as to establish a unified approach to primary health care;

4. the maximum use of ongoing community activities, especially developmental ones, for the promotion of primary health care.58

Invited to speak on this occasion, McGilvray observed, “What the Commission had learnt from its mistakes was reflected in the principles set forth in document EB55/9.” He went on to urge the board to give its enthusiastic support for the policy statement constituted by that document, and pledged the resources of the commission in implementing it.59

CONCLUSION

How dramatic a change primary health care was for WHO can be seen in the contrast between it and the ideas and approaches being promoted several years earlier concerning how best to develop national health systems. Instead of the “top-down” perspective of health planning and systems analysis, priority was now being given to the “bottom-up” approaches of community involvement and development, but without losing sight of the importance of planning and informed decisionmaking. This article documents how and when this shift took place, but it does not capture the courage that it took for Mahler to challenge the organization to rethink its approach to health services development or for Newell to respond to that challenge in the way he did.

Once Mahler took command, he moved quickly to make known his thinking on how health services should be developed. In March 1974, for example, he discussed with Newell’s senior staff how he envisioned their objectives. He especially stressed the objective of “pursu[ing] the idea of community participation (and its logical bottoms-up orientation) to the maximum degree possible.”60

In January 1975, Newell formally created the Primary Health Care program area, whose members included those who had drafted the report to the executive board. While there was mixed reaction within WHO to this new priority, a wide range of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) joined forces in what soon became the NGO Committee on Primary Health Care. This group of organizations prepared for the International Conference on Primary Health Care held at Alma-Ata in September 1978 in an independent manner, thus helping to keep WHO on track.

For those of us in WHO committed to the primary health care approach, working with members of this committee was of prime importance. At the psychological level, the constant positive feedback helped us “keep the faith.” At the professional level, new opportunities opened up that led to projects that would have been difficult, if not impossible, to pursue in earlier years.

That primary health care in time was forced to take second billing to “selective” primary health care in no way detracts from its importance. The same reasons that led to it emerging as a force in public health in the 1970s apply equally, if not more so, today. Under new leadership, WHO has recently reintroduced primary health care onto the agenda of the governing bodies, and nongovernmental voices are again pressuring WHO to make primary health care its priority for the coming decades.61 It is too soon to judge whether this will happen. Sadly, however, the CMC will no longer be involved with whatever emerges, as it was effectively disestablished in the 1990s.

Acknowledgments

I thank the reviewers of earlier versions of this article whose comments helped me to totally revise its structure, alter its tone, and expand on some points of greater relevance today. I acknowledge with thanks the encouragement, comments, and suggestions received from Dr Ed Brown, Dr Jack Bryant, Dr Marcos Cueto, Dr Hakan Hellberg, Jeanne Nemec, Jane Newell, Dr Gunawan Nugroho, Maga Skold, Dr Jerry Stromberg, Dr Carl Taylor, and Dr Joe Wray. I also thank Ineke Deserno, head of Records and Archives, WHO, Geneva, for making available documents from the WHO Archives.

Peer Reviewed

Endnotes

- 1.Methodology of Planning an Integrated Health Programme for Rural Areas, Second Report of the Expert Committee on Public-Health Administration (Geneva: World Health Organization [WHO], 1954), WHO Technical Report Series 83. [PubMed]

- 2.WHO, “The Work of WHO 1966,” Official Records No. 156, Geneva, 1967, vii.

- 3.WHO, “The Work of WHO 1967,” Official Records No. 164, Geneva, 1967, vii.

- 4.Litsios S., “A Programme for Research in the Organization and Strategy of Health Services” (paper presented at the WHO Director General’s Conference, June 25, 1969). WHO Headquarters, Geneva.

- 5.Not suggested by the WHO Secretariat, this study resulted from a strong push by the Soviet representative to the board, Dr D. Venediktov. See S. Litsios, “The Long and Difficult Road to Alma-Ata: A Personal Reflection,” International Journal of Health Services 32 (2002): 709–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO, “Organizational Study of the Executive Board on Methods of Promoting the Development of Basic Health Services” (Geneva: WHO, 1972), document EB49/WP/6, 19–20.

- 7.WHO, Executive Board 49th Session, document EB49/SR/14 Rev, Geneva, 1973, 218.

- 8.WHO, Official Records No. 206, Annex 11, Geneva, 1973, 105.

- 9.WHO, Official Records No. 206, Annex 11, 107.

- 10.WHO, Official Records No. 206, Annex 11, 108.

- 11.WHO, Official Records No. 206, Annex 11, 109.

- 12.Handbook of Resolutions and Decisions of the World Health Assembly and Executive Board, Volume 2, 1973–1984 (Geneva: WHO, 1985), 18.

- 13.Memorandum from P. Dorolle (outgoing WHO deputy director general) to all regional directors, July 25, 1973, WHO Archives, Fonds Records of the Central Registry, third generation of files, 1955–1983 (WHO.3), file N61/348/77.

- 14.Djukanovic Voyo and Edward P. Mach, eds., Alternative Approaches to Meeting Basic Health Needs of Populations in Developing Countries (Geneva: WHO, 1975); Kenneth W. Newell, ed., Health by the People (Geneva: WHO, 1975).

- 15.McGilvray J. C., The Quest for Health and Wholeness (Tübingen, Germany: German Institute for Medical Mission, 1981), xv; J. C. McGilvray, “The International and Ecumenical Dimensions of DIFAM’s Contribution to the Healing Ministry of the Church,” May 18, 1990, 5.

- 16.Christian Medical Commission (CMC), First Meeting, Geneva, September 1968, 1.

- 17.CMC, First Meeting, 3.

- 18.CMC, First Meeting, 1.

- 19.McGilvray, Quest for Health, 9.

- 20.Quoted in McGilvray, Quest for Health, 13.

- 21.Ibid., 25.

- 22.Ibid., 25.

- 23.Ibid., 113.

- 24.Bryant later adapted this paper for publication as J. H. Bryant, “Principles of Justice as a Basis for Conceptualizing a Health Care System,” International Journal of Health Services 7 (1977): 707–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CMC, Annual Report 1973. (Bossey, Switzerland: CMC, 1973), 32–33.

- 26.Ibid., 38–44.

- 27.CMC’s letter of application for nongovernmental organization (NGO) relationship with WHO, February 3, 1969, WHO Archives, Fonds Records of the Central Registry, third generation of files, 1955–1983 (WHO.3), file N61/348/77.

- 28.CMC, 1970. Annual Meeting, Bossey, Switzerland, September 1970, 60.

- 29.CMC, First Meeting, 28.

- 30.“The Commission’s Current Understanding of its Task” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the Christian Medical Commission, September 2–6, 1968).

- 31.McGilvray, Quest for Health, 57.

- 32.Newell K.W., ed, Health by the People (Geneva: WHO, 1975), 103.

- 33.Wray Dr J., written communication, July 28, 2003.

- 34.Newell invited Nugroho to join WHO, which he did in late 1974.

- 35.McGilvray, Quest for Health, 60.

- 36.Newell, Health by the People, 71.

- 37.Arole Rajanikant, Contact, occasional paper No. 10, August 1972; Dr Ed Brown, written communication, August 6, 2003.

- 38.Newell, Health by the People, 38.

- 39.Ibid., 41.

- 40.Behrhorst Carroll, Contact, occasional paper No. 19, February 1974. I could not determine when Newell learned of this project. By early 1975, as reported in a meeting of the Executive Committee of the CMC (January 17–18, 1975), WHO was “considering the possibility of setting up a training centre in Chimaltenango, as it feels that there is much to be learnt from this project.” To the best of my knowledge this never materialized.

- 41.Brown T. M. and E. Fee, “Sidney Kark and John Cassel: Social Medicine Pioneers and South African Emigrés,” American Journal of Public Health 92 (2002): 1744–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stromberg Dr J., written communication, March 23, 2004. Stromberg, who was a social scientist in WHO and deeply involved in promoting community participation, was at the dinner with Kark.

- 43.Kark S. L. and J. Cassel, “The Pholela Health Centre: A Progress Report,” South African Medical Journal 26 (1952): 101–104, 131–136; reprinted in American Journal of Public Health 92 (2002): 1743–1747.14913265 [Google Scholar]

- 44.The CMC had obtained an NGO relationship with WHO in 1970, but until 1974, that relationship had not developed beyond personal ties between staff members of the 2 organizations.

- 45.Hellberg Dr Hakan, written communication, July 22, 2003. Hellberg was associate director of the CMC from 1968 to 1972 and subsequently a senior WHO staff member. Dr Pierre Dorolle was Candau’s deputy.

- 46.Stromberg Dr Jerry, written communication, November 4, 2003.

- 47.McGilvray letter from author’s personal file. I remember being told at the time that Newell was the only WHO director present who reacted positively to these discussions.

- 48.Newell Mrs Jane, written communication, August 25, 2003.

- 49.Memorandum dated March 26, 1974, from Newell to Lambo on the subject of the CMC, WHO Archives, Fonds Records of the Central Registry, third generation of files, 1955–1983 (WHO.3), file N61/348/77.

- 50.The joint statement, dated May 27, 1974, took the form of a memorandum from Barrow and Newell to McGilvray and Mahler, WHO Archives, Fonds Records of the Central Registry, third generation of files, 1955–1983 (WHO.3), file N61/348/77.

- 51.Ibid., 5.

- 52.Letter dated July 22, 1974, from McGilvray to Mahler, WHO Archives, Fonds Records of the Central Registry, third generation of files, 1955–1983 (WHO.3), file N61/348/77.

- 53.CMC, Seventh Annual Meeting, Zurich, Switzerland, July 1974, 3–6.

- 54.Newell, Health by the People, xi. [PubMed]

- 55.Ibid., 192.

- 56.WHO, Handbook of Resolutions and Decisions of the World Health Assembly and Executive Board, Volume 2, 1973–1984.

- 57.WHO, “Documents for 55th Session of the EB,” January 1975, document EB55/9.

- 58.Ibid., 4.

- 59.WHO, “Verbatim Record of 55th EB,” document EB/55/SR/6, p. 5.

- 60.Litsios S., My Reaction to Meeting With Dr Mahler & Dr Chang, ADG −13 March 1974, memorandum to Newell dated March 18, 1974, in author’s files.

- 61.Litsios S., “Primary Health Care, WHO, and the NGO Community,” Development 47 (2004): 57–63. [Google Scholar]