Abstract

Occupational health remains neglected in developing countries because of competing social, economic, and political challenges. Occupational health research in developing countries should recognize the social and political context of work relations, especially the fact that the majority of developing countries lack the political mechanisms to translate scientific findings into effective policies.

Researchers in the developing world can achieve tangible progress in promoting occupational health only if they end their professional isolation and examine occupational health in the broader context of social justice and national development in alliance with researchers from other disciplines. An occupational health research paradigm in developing countries should focus less on the workplace and more on the worker in his or her social context.

HEALTH AND SAFETY innovations in the workplace, with low-cost and locally relevant solutions, have been initiated in several developing countries.1–3 However, occupational health remains neglected in most developing countries under the pressure of overwhelming social, economic, and political challenges.4–6 The traditional workplace-oriented occupational health has proven to be insufficient in the developing world, and tangible progress in occupational health can be achieved only by linking occupational health to the broader context of social justice and national development.7–10

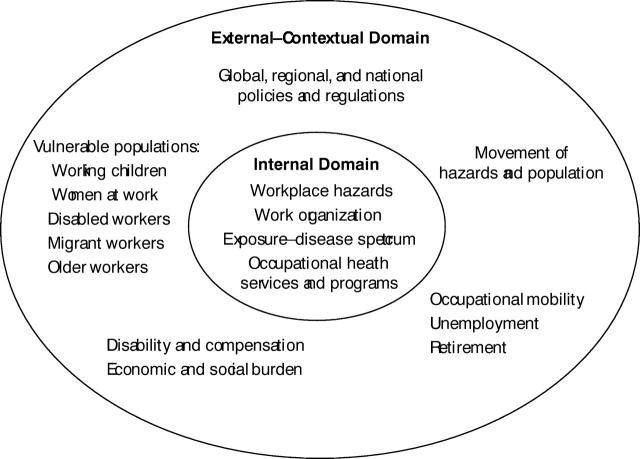

In this article, I describe the history and current state of occupational health in industrialized countries to argue that occupational health researchers in developing countries must focus less on the workplace and more on the worker and the worker’s social context in which work-place practices are embedded. Leading occupational health research issues are grouped into 2 domains: an internal domain, which focuses on the workplace (microenvironment), and an external–contextual domain, which examines the wider social and global issues. Figure 1 ▶ lists examples of issues that are addressed in each domain.

FIGURE 1—

Domains of occupational health research.

LESSONS FROM THE INDUSTRIALIZED WORLD

A striking characteristic of occupational health in the industrialized world, and a message frequently disseminated in developing countries, is the contribution of science to progress in occupational health through data collection, ongoing assessment of problems, and innovative technological solutions.11 However, what is rarely mentioned is the presence in developed countries of a political mechanism that mediates the translation of scientific findings into policies and regulations that are enforced by specialized agencies. In fact, very little progress in occupational health has been or can be achieved without such a mechanism.

The history of occupational health in the United States and other industrially developed countries shows that progress has not been linear; occupational health has been influenced primarily by events outside the field, namely social movements and changes in the delivery of health care and perception of health.11–14 Setbacks and regressions caused by changes in the political mood and the popular attitude toward work-related risks are not infrequent.12,15 Nevertheless, the occupational health community has succeeded, even in less favorable times, in addressing occupational health issues by participating in a process of risk assessment and risk management that “determines” the validity and strength of scientific findings versus the economic, technological, and sociopolitical feasibility of intervention.16

Occupational health researchers in industrialized countries investigate the effect of work on health, depending on a process that translates their scientific findings into policy. A case in point is the current National Occupational Health Research Agenda in the United States, which, in spite of an iterative process of consultation, still focuses on disease and injury, work environment and workforce, and research tools and approaches.17 Those priorities are limited mostly to the internal domain of occupational health, although the National Occupational Health Research Agenda encompass the understanding of the health effects of long-term exposure to low hazard concentrations as well as the identifications of early indicators of exposure and subclinical health effects. The workplace-centered approach, although limited, serves well the cause of occupational health in developed countries; this is not necessarily the case for occupational health in developing countries. By contrast, without similar parliamentary or democratic political mechanism(s) and risk assessment processes, the industrialized model cannot be imported to developing countries.5

OPTIONS FOR OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH RESEARCH IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

Current deficiencies of occupational health in the developing world—reported in such disparate locations as Bangladesh,18 Central America,19 Lebanon,20 South Africa,8 and Thailand21—are attributed to a lack of governmental interest in occupational health, poor data and data collection systems, and weak enforcement of health and safety regulations.

Occupational health professionals have repeatedly wondered why governments in these countries are relatively unconcerned with occupational health, and why occupational health is absent where it is most needed,22 particularly given that clear empirical links exist between good occupational health practices, a healthier labor force, and improved productivity. Indeed, workplace interventions such as proper occupational hygiene and ergonomic practices have been presented as one of the tools to break the cycle of poverty, because these improve productivity, salaries, and, consequently, living conditions.5,23,24 However, this sequence of positive impacts is not clear to decisionmakers in most developing countries, who still perceive occupational health as a luxury.

Therefore, many occupational health professionals advocate that occupational health research in developing countries focus on gathering and disseminating information on workplace hazards to make a stronger and more convincing case for the importance of occupational health.25 This claim is further substantiated by the few internationally funded research projects that clearly show an effect on capacity building and change in practices or policies.19,26–28 It is true that traditional occupational health research is necessary in developing countries. However, there are several reasons why traditional occupational health research is not sufficient.

Although it is true that “assessment of the health impact of occupational risks is important for social recognition of these risks, to plan and facilitate adequate interventions for their prevention and to adequately manage the health burdens they cause,”29 the primary obstacle to occupational health in most developing countries remains the lack of a political mechanism that translates information into action. In reality, policymakers in the developing world do not lack information. A casual walk through any type of workplace in most developing countries would easily uncover the range of unsafe practices and occupational hazards. Policymakers are still driven by the need to address other “more pressing” social and health issues30 that are politically less complicated and more saleable to the general public.

The solution to occupational health problems in developing countries therefore requires not only technological innovation31 but also significant institutional and legal developments.32 Occupational health researchers should understand the “political economy” of the labor market at global, regional, and nation–state levels.33,34 They must recognize the leading role of forces fighting for social justice, particularly the role of organized labor, which is instrumental to advancing national occupational health agendas and ratifying international labor laws, notwithstanding the repression they face and their questionable representation of the interest of their constituency in many developing countries.31–36 Occupational health researchers in developing countries also must be alert to the potentially negative effect of global trade on the health and safety of poor and marginalized workers.37 Research should contribute to the international call to hold multinational corporations accountable to international ethical occupational health practices.38

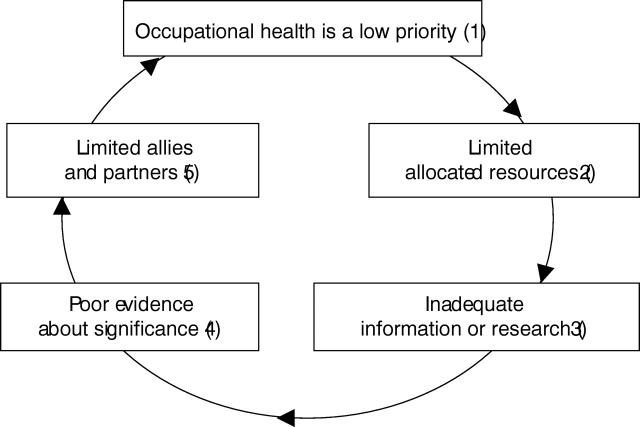

Consequently, a different research paradigm is warranted for occupational health research in developing countries. The paradigm should make the most efficient use of existing assets and minimize conflict with practical realities. Specifically, instead of focusing on the workplace as an isolated entity and moving outward to the wider social and political arena as done in occupational health research in industrialized countries, occupational health research in the developing world should focus on the social and political issues and then move inward to address the particularities of the workplace (i.e., from the “external–contextual domain” to the “internal domain”). This approach builds a wider alliance up front with social scientists, economists, political scientists, unionists, nongovernmental organizations, women’s organizations, human rights groups, and others as an entry point into the occupational health field. In other words, the occupational health vicious “cycle of neglect” in developing countries (Figure 2 ▶) should be broken at the allies’ link (step 5) to build consensus22 and “fundamental change in the attitude” (emphasis added) toward the day-to-day exposure to risk.39

FIGURE 2—

The occupational health “cycle of neglect” in developing countries.

Occupational health research should be “mainstreamed” as an integral component of public and environmental health re-seach7,8,40,41 and placed in its broader social and cultural context42 by addressing issues such as globalization, the importation of health hazards, women at work, migrant workers, and child labor, in addition to the narrower social and economic burdens of work-related diseases and injuries. This approach underscores the often forgotten multidisciplinary nature of our profession and calls for research that considers social and economic development within the broader public health context.12,23 This occupational health research approach also would increase the pool of professionals, community organizations, unions, and activists concerned with occupational health. Involving unions and community organizations in defining the occupational health research agenda ensures its relevance to people striving for better working and living conditions in their countries. It also should provide evidence to grassroots intervention programs to improve the working and living conditions of workers in the face of official neglect. By such means, occupational health research may help create responsive political mechanisms within developing countries.

SELECTED ILLUSTRATIONS

Silicosis, asbestosis, lead toxicity, and pesticide poisoning represent striking case studies in which an occupational illness “stepped out” of the isolation of the workplace and into the realm of environmental and public health concerns and, more importantly, into the general public consciousness.43 These occupational diseases were eventually recognized as social diseases rather than occupational illnesses44,45 and were thus perceived by the public as scourges against social justice and basic human rights. This transformation in the public’s risk and health perceptions led to sweeping reforms in work-place health and safety practice and regulations in the industrialized countries.

Similarly, in the developing world, several innovative, integrative occupational health programs have succeeded in examining the interplay between work and widespread nonoccupational illnesses, such as AIDS and tuberculosis, and thus have succeeded in linking occupational and environmental health.40,46 Such initiatives are perfect examples of programs that take occupational health research out of its “splendid isolation.”47 Child labor presents yet another example in which partnership with other researchers from the disciplines of social science, public policy, and economics is built to counteract the social and economic basis for child labor. 48

Two occupational health issues are presented to further illustrate the point that an isolated, workplace-based approach falls short of responding to the challenges of occupational health in developing countries.

Women and Work

In addition to their domestic responsibilities of childbearing, child rearing, and family care, women in the developing world have worked in the agricultural and informal sectors for millennia. However, because their work is usually not valued monetarily in these sectors, it is often discounted and rendered invisible. In the formal sector as well, gender inequalities are commonplace in such areas as limited job opportunities, limited tracks for promotion and leadership responsibilities, and discrimination based on work hazards. Women’s work, particularly in the developing world, is not adequately protected by national policies and is generally restricted by traditional social norms and such misperceptions that women’s work is less significant, is merely supplementary, or is unskilled. Hence, there is an urgency to “examine the wider impact of women’s different productive and reproductive roles on their occupational health.”(emphasis added)49 Again, this challenge to occupational health transcends the boundaries of the workplace and requires a multi-disciplinary approach in which occupational health researchers partner with other social scientists and advocates.

Use of Pesticides

Understanding and minimizing the exposure of farmers and their families to pesticides in the developing world cannot be viewed as an isolated medical problem or a mere technical problem. It requires an understanding of farmers’ knowledge, values, and beliefs; of the contribution of the agricultural sector to the overall economy; and of the role and power of international and national agribusiness operating in a country. Occupational health research, therefore, should be part of a larger movement to ensure just and sustainable agricultural development. For example, occupational health should promote integrated pest management practices, organic farming methods, control of the import of illegal or banned chemicals, and more responsibility from agro-chemical corporations.

IMPLICATIONS

The call for a different occupational health research paradigm carries 3 major implications. The first concerns the training of occupational health researchers, especially those trained in industrialized countries. Occupational health research from the developing countries has been criticized as not being innovative or as being an extension of research conducted in the country of graduate training, except for suboptimal assessment of exposures and health outcomes.25,50 This is not an outcome of lack of training; on the contrary, in most cases, it is a direct result of focused individuals with advanced training who, on return to their home countries, had to produce research in a socially and economically constricted environment where human and financial resources are limited and data are lacking. Therefore, in addition to their traditional technical and methodological training, occupational health researchers from the less-developed countries should be exposed to contextual global, social, and political issues and to the quantitative and qualitative research methodologies of economics and social sciences as they relate to occupational health. This additional education will equip them with better tools to understand and explain the world of work and will better prepare them for new, more effective roles as researchers, as well as practitioners and activists, in underprivileged communities.

The second implication concerns the mission statements and research interest of leading occupational health journals. To illustrate, the abstracts of all articles published in 1999 in 4 internationally recognized and professionally recommended occupational health journals were reviewed—2 American (American Journal of Industrial Medicine and Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine), 1 British (Occupational and Environmental Medicine), and 1 Scandinavian (Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment, and Health). The majority of published articles focused on occupational health issues within the workplace (internal domain). Articles that focused on issues within the external–contextual domain were less frequent, probably because they migrated to specialized policy and social science journals less accessible to occupational health researchers. Because the occupational health journals play a key role in the scientific training and professional outlook of occupational health trainees from the developing nations, it is vital that these journals offer a more comprehensive and relevant perspective.

The third implication is the need to rethink indicators for achievement and progress in occupational health. Objective indicators, such as fatal and nonfatal work-related health outcomes, are crucial for the measurement of progress in the field,51 but they cannot be the only yardstick used, especially in developing countries. These countries lack historical data or current surveillance systems. In most, even basic objective indicators appear unattainable, at least in the near future. In terms of occupational health progress and achievement, process (e.g., training of professionals; development of professional theory and methods, programs, advocacy, research, and partnerships) needs to be recognized as much as outcome (e.g., rate of occupational injuries and diseases).

CONCLUSIONS

Occupational health long has been recognized as a complex field,10 and any attempt to “box” it within a rigid framework that deals only with worker-hazard interaction runs the risk of marginalizing the field. I challenge the claim that occupational health is an unaffordable luxury to be addressed after economic development is secured. Instead, I argue that occupational health is a necessity and call for a revised occupational health research paradigm in developing countries that focuses less on the workplace and more on the workers in their social contexts.46,52 A contextual, social justice orientation of occupational health research, as opposed to the narrow traditional approach, places occupational health researchers in tandem with other stakeholders in the call for a just and healthy society. In addition, only by becoming a tool for social change rather than a target can occupational health research effectively understand the hazards of work and its effects on workers and the community in developing countries.

This argument echoes what many occupational health professionals from both hemispheres have repeatedly advocated.6,10,35,50,53 The paradigm argued for here also facilitates more research and collaborative opportunities for occupational health researchers nationally, regionally, and internationally, as reported in a few leading initiatives.19,26,41,46 Forging a new pathway for occupational health research in developing countries will not be an easy task. However, staying with the prevailing paradigm means a prolongation of neglect, ineffectiveness, and professional stagnation.

Acknowledgments

This work was initiated at the American University of Beirut and further developed during my sabbatical year as a visiting Fulbright scholar at the Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute in New Jersey. I thank Abbas El-Zein, Michael Gochfeld, Rima Habib, Berj Hatjian, Norbert Hirschhorn, Kirk Hooks, Howard Kipen, and Karen Messing for their valuable conceptual comments and editorial review. I also thank Omar Dewachi for his help in the review of journal abstracts.

Human Participant Protection No human participants were involved in this study.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Kawakami T, Batino JM, Khai TT. Ergonomic strategies for improving working conditions in some developing countries in Asia. Ind Health. 1999;37:187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kogi K. Collaborative field research and training in occupational health and ergonomics. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998;4:189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koplan JP. Hazards of cottage and small industries in developing countries. Am J Ind Med. 1996;30:123–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahasan MR, Partanen T. Occupational health and safety in the least developed countries—a simple case of neglect. J Epidemiol. 2001;11:74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Neill DH. Ergonomics in industrially developing countries: does its application differ from that in industrially advanced countries? Appl Ergon. 2000;31:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiani DC, Durvasula R, Myers J. Occupational health in developing countries: review of research needs. Am J Ind Med. 1990;17:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swuste P, Eijkemans G. Occupational safety, health, and hygiene in the urban informal sector of sub-Saharan Africa: an application of the Prevention and Control Exchange (PACE) program to the informal-sector workers in healthy city projects. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joubert DM. Occupational healthchallenges and success in developing countries: a South African perspective. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michaels D, Barrera C, Gacharna MG. Economic development and occupational health in Latin America: new directions for public health in less developed countries. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:536–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendes R. The scope of occupational health in developing countries. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:467–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashford NA, Caldart CC. Technology, work, and health. In: Technology, Law, and the Working Environment. Rev ed. Washington, DC: Island Press; 1996:1–40.

- 12.Cullen MR. Personal reflections on occupational health in the twentieth century: spiraling to the future. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emmett EA. Occupational health and safety in national development—the case of Australia. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23:325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter D. The Diseases of Occupations. 6th ed. London, England: Hodder & Stoughton; 1978.

- 15.LaDou J. The rise and fall of occupational medicine in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma DK, Purdham JT, Roels HA. Translating evidence about occupational conditions into strategies for prevention. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenstock L, Olenec C, Wagner GR. The National Occupational Research Agenda: a model of broad stakeholder input into priority setting. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:353–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahasan MR, Mohiuddin G, Vayrynen S, Ironkannas H, Quddus R. Work-related problems in metal handling tasks in Bangladesh: obstacles to the development of safety and health measures. Ergonomics. 1999;42:385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wesseling C, Aragon A, Morgado H, Elgstrand K, Hogstedt C, Partanen T. Occupational health in Central America. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nuwayhid IA. Occupational health in Lebanon: overview and challenges. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1995;1:349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yingratanasuk T, Keifer MC, Barnhart S. The structure and function of the occupational health system in Thailand. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998;4:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kromhout H. Occupational hygiene in developing countries: something to talk about? Ann Occup Hyg. 1999;43:501–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elgstrand K. Occupational safety and health in developing countries. Am J Ind Med. 1985;8:91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khogali M. A new approach for providing occupational health services in developing countries. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1982;8(suppl 1):152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy BS, Kjellstrom T, Forget G, Jones MR, Pollier L. Ongoing research in occupational health and environmental epidemiology in developing countries. Arch Environ Health. 1992;47:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elgstrand K. Development by training: international training programs for occupational health and safety professionals. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2001;7:136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breman JG, Bridbord K. The John E. Fogarty International Center: collaborative projects in international environmental and occupational health. Partnerships and progress. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1999;5:198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutherford BA, Forget G. The impact of support of occupational health research on national development in developing countries. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1997;3:68–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loewenson RH. Health impact of occupational risks in the informal sector in Zimbabwe. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998;4:264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joyce S. Growing pains in South America. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105:794–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sass R. The dark side of Taiwan’s globalization success story. Int J Health Serv. 2000;30:699–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaDou J. International occupational health. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2003;206:303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levenstein C, Wooding J. Work, Health, and Environment. Old Problems, New Solutions. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1997.

- 34.Johansson M, Partanen T. Role of trade unions in workplace health promotion. Int J Health Serv. 2002;32:179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frumkin H. Across the water and down the ladder: occupational health in the global economy. Occup Med. 1999;14:637–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giuffrida A, Iunes RF, Savedoff WD. Occupational risks in Latin America and the Caribbean: economic and health dimensions. Health Policy Plan. 2002;17:235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loewenson R. Globalization and occupational health: a perspective from southern Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:863–868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.London L, Kisting S. Ethical concerns in international occupational health and safety. Occup Med. 2002;17:587–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bayer R. Editor’s note: whither occupational health and safety? Am J Public Health. 2000;90:532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ory FG, Rahman FU, Shukla A, Zwaag R, Burdorf A. Industrial counseling: linking occupational and environmental health in tanneries of Kanpur, India. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1996;2:311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu X, Christiani DC. Occupational health research in developing countries: focus on US–China collaboration. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1995;1:136–141. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubio CA. Ergonomics for industrially developing countries: an alternative approach. J Hum Ergol (Tokyo). 1995;24:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kipen HM. The next asbestos. The identification and control of environmental and occupational disease. Adv Mod Environ Toxicol. 1994;22:425–430. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosner D, Markowitz G. Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the Politics of Occupational Disease in Twentieth-Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1991.

- 45.Corn JK. Response to Occupational Health Hazards. A Historical Perspective. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1992.

- 46.Williams B, Campbell C. Creating alliances for disease management in industrial settings: a case study of HIV/ AIDS in workers in South African gold mines. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998;4:257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kromhout H. Introduction: an international perspective on occupational health and hygiene. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:111–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forastieri V. Children at Work: Health and Safety Risks. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Office, 1997.

- 49.Loewenson RH. Women’s occupational health in globalization and development. Am J Ind Med. 1999;36:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeyaratnam J. 1984 and occupational health in developing countries. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1985;11:229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi K, Aw TC, Koh D, Wong TW, Kauppinen T, Westerholm P. Developing national indicators for occupational health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23:392–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilhorst TJ. Appraisal of risk perception in occupational health and safety research in developing countries. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1996;2:319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Partanen TJ, Hogstedt C, Ahasan R, et al. Collaboration between developing and developed countries and between developing countries in occupational health research and surveillance. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999;25:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]