Abstract

Objectives. We estimated the prevalence of cigarette smoking and the extent of environmental tobacco smoke exposure (ETS) in the general population in China.

Methods. A cross-sectional survey was conducted on a nationally representative sample of 15540 Chinese adults aged 35–74 years in 2000–2001. Information on cigarette smoking was obtained by trained interviewers using a standard questionnaire.

Results. The prevalence of current cigarette smoking was much higher among men (60.2%) than among women (6.9%). Among nonsmokers, 12.1% of men and 51.3% of women reported exposure to ETS at home, and 26.7% of men and 26.2% of women reported exposure to ETS in their workplaces. On the basis of our findings, 147358000 Chinese men and 15895000 Chinese women aged 35–74 years were current cigarette smokers, 8658000 men and 108402000 women were exposed to ETS at home, and 19072000 men and 55372000 women were exposed to ETS in their workplaces.

Conclusions. The high prevalence of cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure in the Chinese population indicates an urgent need for smoking prevention and cessation efforts.

Cigarette smoking is a major public health challenge worldwide. Whereas cigarette smoking caused an estimated 3 million annual deaths worldwide at the end of the 20th century, this number is predicted to soar to more than 10 million by 2020, with the burden of smoking-related mortality shifting from developed to developing nations.1–3 By 2030, 70% of annual smoking-related deaths worldwide will occur in developing countries.4

With a population of 1.2 billion, China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of tobacco.5 Several epidemiological studies conducted in China have documented that cigarette smoking increases mortality from cancer and from respiratory and cardiovascular disease.6–10 Two previous national surveys have reported a high prevalence of cigarette smoking in Chinese men.5,11 However, detailed information on home and workplace exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) was not reported in these surveys.

The objectives of this study were to estimate the prevalence and number of cigarette smokers in the general adult population in China, to examine the extent of ETS exposure in China, and to investigate the contribution of home and workplace exposure to ETS.

METHODS

The International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia (InterASIA) was a cross-sectional study of cardiovascular disease risk factors in the general population aged 35–74 years in China and Thailand. Details of the study’s design and methods have been published elsewhere.12 In brief, InterASIA used a 4-stage stratified sampling method to select a nationally representative sample in China. A total of 19012 persons were randomly selected and were invited to participate. A total of 15838 persons (83.3%) completed the survey and examination. The analysis reported in this article was restricted to the 15540 adults who were aged 35–74 years at the time of the survey.

Trained research staff administered a standard questionnaire including questions from the lifetime smoking questionnaire used in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.13 The questionnaire was translated into Chinese and translated back into English independently by investigators who were fluent in both languages. Information about current and former cigarette smoking, including age at which smoking was initiated, years of smoking, and cigarettes smoked per day, was obtained. Cigarette smokers were defined as persons who smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Those who were smoking tobacco products at the time of the survey were classified as current smokers.

Reported exposure to ETS at home was assessed by asking study participants whether any household member smoked cigarettes in their home, and if so, how many cigarettes per day were smoked in this setting. Study participants were classified as having been exposed to ETS at home if any household member smoked. Study participants were also asked how many hours per day they were close enough in proximity to tobacco smoke at work that they could smell it. Study participants were classified as having exposure to ETS at work if they could smell tobacco smoke at least 1 hour per day at work. These ETS exposure questions have been validated by serum cotinine measures in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III.14

The prevalence and mean levels were weighted to represent the total Chinese adult population aged 35–74 years. The weights were calculated based on the 2000 China Population Census data and the InterASIA sampling scheme and took into account several features of the survey including oversampling for specific age or geographic subgroups, nonresponse, and other demographic or geographic differences between the sample and the total population. Standard errors were calculated by a technique appropriate to the complex survey design. All data analyses were conducted using Stata 7.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Tex) software.

RESULTS

Overall, 60.2%, or an estimated 147358000, Chinese men aged 35–74 years had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and were current cigarette smokers. An additional 10.6%, or an estimated 25872000, Chinese men in the same age range had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime but were not current smokers at the time of the survey (Table 1 ▶). The prevalence of current and former cigarette smokers was much lower among women, at 6.9% (an estimated 15895000 women) and 2.0% (an estimated 4553000 women), respectively. The prevalence of current cigarette smokers was higher in younger than in older men, but the prevalence of former smokers was higher in older than in younger men. The prevalence of both current and former cigarette smokers increased with age among women. The age-standardized prevalence of current cigarette smokers was significantly higher among rural residents compared with male (61.6% vs 54.5%; P < .001) and female (7.8% vs 3.4%; P <.001) urban residents. The age-standardized prevalence of current smokers was similar among men in North and South China (58.6% vs 61.2%; P =0.08) and was significantly higher among women in South China than in North China (7.8% vs 5.6%; P <.01).

TABLE 1—

Prevalence and Estimated Number of Cigarette Smokers Aged 35–74 Years by Gender and Age Group: China, 2000–2001

| Current a | Former b | Never c | ||||

| Age Group, years | % (SE) | No.d (SE) | % (SE) | No.d (SE) | % (SE) | No.d (SE) |

| All | 34.3 (0.5) | 163 253 (2568) | 6.4 (0.3) | 30 425 (1244) | 59.4 (0.5) | 282 892 (2522) |

| Men | ||||||

| 35–74 | 60.2 (0.8) | 147 358 (2522) | 10.6 (0.5) | 25 872 (1130) | 29.2 (0.7) | 71 491 (1878) |

| 35–44 | 63.3 (1.2) | 60 190 (1728) | 7.0 (0.6) | 6684 (584) | 29.7 (1.1) | 28 218 (1258) |

| 45–54 | 62.3 (1.4) | 46 557 (1729) | 10.4 (0.9) | 7793 (659) | 27.3 (1.3) | 20 442 (1087) |

| 55–64 | 57.8 (1.6) | 26 015 (1136) | 12.8 (1.0) | 5745 (482) | 29.4 (1.5) | 13 226 (783) |

| 65–74 | 48.9 (2.3) | 14 596 (942) | 18.9 (1.7) | 5650 (566) | 32.2 (2.1) | 9605 (771) |

| Women | ||||||

| 35–74 | 6.9 (0.4) | 15 895 (963) | 2.0 (0.2) | 4553 (540) | 91.2 (0.5) | 211 401 (2469) |

| 35–44 | 4.7 (0.6) | 4209 (526) | 0.8 (0.2) | 751 (207) | 94.5 (0.6) | 84 459 (1860) |

| 45–54 | 6.6 (0.8) | 4600 (605) | 2.1 (0.5) | 1486 (345) | 91.3 (0.9) | 64 138 (1733) |

| 55–64 | 8.8 (0.9) | 3691 (410) | 2.5 (0.6) | 1056 (243) | 88.7 (1.1) | 37 087 (1236) |

| 65–74 | 11.2 (1.4) | 3395 (451) | 4.1 (0.9) | 1259 (275) | 84.7 (1.6) | 25 718 (1251) |

aCurrent cigarette smokers were those who smoked at the time of the survey and had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes.

bFormer cigarette smokers were those who had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but were no longer smoking at the time of the survey.

cNever smokers were those who had never smoked or smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes.

dEstimated population in thousands.

Among current cigarette smokers, the average number of cigarettes smoked was 20 per day for men and 7 per day for women. Among current cigarette smokers, the average number of pack-years of cigarette smoking, an estimate of lifetime exposure (the product of packs of cigarettes per day and years of smoking), was 20 for men and 11 for women. As expected, pack-years of cigarette smoking increased with age. The mean age of starting cigarette smoking was 22.0 years for men and 23.7 years for women. Younger smokers reported an earlier age of initiation than did the older smokers.

Of the nonsmokers, 41.4%, or an estimated 117060000, Chinese men and women aged 35–74 years reported exposure to ETS at home (Table 2 ▶). The prevalence of persons who reported home exposure to ETS was much higher among women (51.3%) compared with men (12.1%). The prevalence of home exposure to ETS was higher in older age groups for men and in younger age groups for women. There were 26.3%, or an estimated 74443000, Chinese men and women aged 35–74 years who reported exposure to ETS at work. The prevalence of persons who reported workplace exposure to ETS was similar among men (26.7%) and women (26.2%). The prevalence of work-place exposure to ETS was higher in younger age groups compared with older age groups.

TABLE 2—

Prevalence of Home or Workplace Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke Among Nonsmokers, by Gender and Age Group: China, 2000–2001

| Home | Workplace | |||

| Age Group, years | % (SE) | Estimated Populationa (SE) | % (SE) | Estimated Populationa (SE) |

| All | 41.4 (0.7) | 117 060 (2110) | 26.3 (0.6) | 74 443 (1809) |

| Men | ||||

| 35–74 | 12.1 (0.9) | 8658 (700) | 26.7 (1.2) | 19 072 (961) |

| 35–44 | 6.0 (1.1) | 1685 (333) | 31.1 (2.0) | 8771 (667) |

| 45–54 | 13.1 (1.9) | 2664 (404) | 29.9 (2.4) | 6106 (562) |

| 55–64 | 19.9 (2.4) | 2634 (344) | 22.9 (2.4) | 3028 (359) |

| 65–74 | 17.5 (3.1) | 1674 (322) | 12.2 (2.5) | 1166 (257) |

| Women | ||||

| 35–74 | 51.3 (0.8) | 10 8402 (2041) | 26.2 (0.7) | 55 372 (1620) |

| 35–44 | 57.5 (1.2) | 48 533 (1463) | 33.8 (1.2) | 28 521 (1184) |

| 45–54 | 51.4 (1.4) | 32 915 (1264) | 25.0 (1.3) | 16 017 (952) |

| 55–64 | 49.7 (1.8) | 18 437 (896) | 20.9 (1.5) | 7732 (634) |

| 65–74 | 33.1 (2.3) | 8516 (708) | 12.1 (1.7) | 3102 (463) |

aIn thousands.

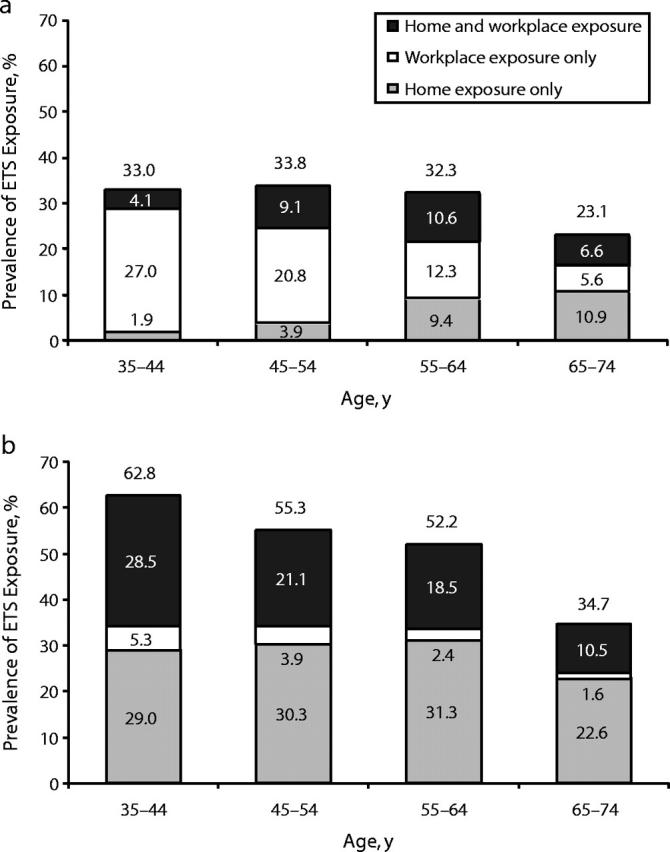

Among nonsmokers, 22.9% of Chinese men and women aged 35–74 years reported exposure to ETS at home only, 7.9% at work only, and 18.4% both at home and at work. Overall, 49.2%, or an estimated 139421000, Chinese men and women nonsmokers aged 35–74 years reported exposure to ETS at home or at work. The percentage of nonsmokers who reported exposure to ETS at home only was much higher among women (29.0%) than among men (5.1%), whereas the percentage of nonsmokers who reported exposure to ETS at work only was much higher among men (19.7%) than among women (3.9%). The percentage of nonsmokers who reported exposure to ETS both at home and at work was much higher among women (22.3%) than among men (7.0%). The prevalence of exposure to ETS at home but not at work was higher in older age groups for men and in younger age groups for women (Figure 1 ▶). The prevalence of exposure to ETS at work but not at home was higher in younger age groups for both men and women.

FIGURE 1—

Prevalence of environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure among nonsmokers by gender and age group in China, 2000–2001.

The age-standardized prevalence of ETS exposure among nonsmoking men was significantly higher in urban compared with rural areas (39.8% vs 29.4%; P <.001) and in North compared with South China (37.4% vs 27.1%; P < .001), mainly because of a higher proportion of work-related ETS exposure in urban and North China. The age-standardized prevalence of ETS exposure among nonsmoking women was similar in urban and rural areas (53.3% vs 55.9%) as well as in North and South China (54.5% vs 55.9%).

Of the nonsmokers, 38.4% of Chinese men and women aged 35–74 years had 1 household member who smoked in their home, 5.0% had 2 household members who smoked in their home, and only 0.6% had 3 or more household members who smoked in their home (Table 3 ▶). The percentages of 1, 2, and 3 or more household members who smoked in their home were higher for women (47.7%, 6.1%, and 0.7%, respectively) than for men (11.0%, 1.8%, and 0.2%, respectively). Among nonsmokers, 9.8%, 12.2%, and 15.0% of Chinese men and women aged 35–74 years reported exposure to ETS at work for 1, 2 to 3, and 4 or more hours per day, respectively (Table 3 ▶). The percent distribution by number of hours per day of exposure to ETS at work was similar among men and women.

TABLE 3—

Percentage of Nonsmokers, by Home Exposure (Number of Household Members Reported Smoking in Their Homes) and Workplace Exposure (Number of Hours Exposed to Cigarette Smoke at Work), Gender, and Age Group: China, 2000–2001

| Exposed,a % (SE) | ||||||

| Smokers per Household | Hours of Exposure per Day | |||||

| Age Group, years | 1 | 2 | ≥ 3 | 1 | 2–3 | ≥ 4 |

| All | 38.4 (0.7) | 5.0 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.1) | 9.8 (0.5) | 12.2 (0.5) | 15.0 (0.6) |

| Men | ||||||

| 35–74 | 11.0 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.1) | 9.1 (0.9) | 11.0 (1.0) | 14.4 (1.0) |

| 35–44 | 6.1 (1.2) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.02 (0.02) | 8.2 (1.3) | 10.9 (1.4) | 17.5 (1.8) |

| 45–54 | 12.0 (1.8) | 1.5 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.3) | 11.5 (2.1) | 11.4 (1.8) | 14.8 (1.8) |

| 55–64 | 16.7 (2.2) | 4.0 (1.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | 10.6 (2.2) | 12.5 (2.5) | 10.6 (2.0) |

| 65–74 | 14.8 (3.0) | 3.2 (1.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 4.1 (1.8) | 8.4 (2.5) | 6.8 (2.7) |

| Women | ||||||

| 35–74 | 47.7 (0.8) | 6.1 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.1) | 10.0 (0.6) | 12.6 (0.6) | 15.3 (0.7) |

| 35–44 | 57.1 (1.2) | 3.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.1) | 9.7 (0.8) | 14.7 (1.0) | 17.4 (1.0) |

| 45–54 | 46.1 (1.5) | 8.6 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.2) | 10.0 (1.1) | 12.3 (1.2) | 14.3 (1.3) |

| 55–64 | 40.8 (1.8) | 10.1 (1.1) | 1.5 (0.4) | 13.0 (1.7) | 10.1 (1.6) | 14.9 (1.8) |

| 65–74 | 30.2 (2.3) | 4.0 (1.1) | 1.1 (0.5) | 7.2 (1.9) | 7.0 (1.7) | 8.3 (2.0) |

aAmong those employed.

CONCLUSIONS

This study indicates that, of Chinese adults aged 35–74 years, 60.2% (147358000) of men and 6.9% (15895000) of women were current cigarette smokers. In addition, 49.2% (139421000) of nonsmokers aged 35–74 years reported exposure to ETS at home or at work. Overall, more than 300 million Chinese adults aged 35–74 years were exposed to active or passive cigarette smoking. This number is very significant because cigarette smoking has become the leading cause of preventable death in China and the world.6–10,15

Two national surveys on the prevalence of cigarette smoking were conducted in China in 1984 and 1996.5,11 In the 1984 national survey, a multistage randomly selected sample of 519600 Chinese men and women aged 15 years or older participated in the survey.11 Overall, the prevalence of cigarette smoking, defined as persons who had ever smoked at least 1 cigarette daily for at least 6 months, was 61.0% among men and 7.0% among women. In the 1996 national survey, 120298 persons aged 15 to 69 years were selected from 145 disease surveillance populations in the 30 provinces in China, using a 3-stage cluster, random sampling method.5 Using the same definition for cigarette smoking as the 1984 survey, the prevalence of current smoking was 63.0% among men and 3.8% among women.

Our study employed a multistage stratified random sampling method to select a representative national sample from the Chinese general population. Cigarette smokers were defined as persons who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime. Our findings cannot be directly compared with the 2 previous national surveys, because of differences in sampling methods and definitions of cigarette smoking. However, our study confirmed the previous findings that the prevalence of current cigarette smoking was extremely high among men. In addition, we found that the prevalence of cigarette smoking among women was higher than previously reported.

This study provides an opportunity to compare the prevalence of cigarette smoking in China with other countries because the survey instruments and definitions for cigarette smoking were identical to those used in other national surveys. The prevalence of cigarette smoking in Western populations was much lower for men and higher for women compared with that noted in China.16–18 For example, the prevalence of current smokers was 26.4% among men and 22.1% among women in the 1997–1998 US National Health Interview Survey.17 The prevalence of cigarette smoking in China was similar to other economically developing countries in Asia.19,20

Our study is among the first surveys to provide detailed information on ETS in the general population in China. Our findings indicated that a high proportion of men and women are exposed to ETS smoke at work in China, which is cause for concern. Prohibition of cigarette smoking in the workplace is not required by law in China.

Epidemiological studies have documented that cigarette smoking is a leading preventable cause of death in China, similar to what is seen in other countries.4,6–10 Exposure to ETS has also been related to an increased risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease in Chinese population as well as in other populations.21–25

Our findings have important public health implications. The high prevalence of cigarette smoking in Chinese men indicates an urgent need for smoking prevention and cessation efforts. Smoking prevention efforts are also needed to further decrease the currently low prevalence of cigarette smoking among women. The large number of men and women being exposed passively to cigarette smoke in their workplace argues for legal prohibition of cigarette smoking in the workplace environment in China.

Acknowledgments

The InterASIA study was funded by a contractual agreement between Tulane University and Pfizer Inc. Several researchers employed by Pfizer Inc. were members of the Study Steering Committee that designed the study. However, the study was conducted, analyzed, and interpreted by the investigators independent of the sponsor.

The InterASIA Collaborative Group: Steering Committee—Jiang He (Co-Principal Investigator), Paul K. Whelton (Co-Principal Investigator), Dale Glasser, Dongfeng Gu, Stephen MacMahon, Bruce Neal, Rajiv Patni, Robert Reynolds, Paibul Suriyawongpaisal, Xigui Wu, Xue Xin, and XinHua Zhang; Participating Institutes and Principal Staff—Tulane University, New Orleans, LA: Jiang He (Principal Investigator [PI]), Lydia A. Bazzano, Jing Chen, Paul Muntner, Kristi Reynolds, Paul K. Whelton, and Xue Xin; University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia: Stephen MacMahon (PI), Neil Chapman, Bruce Neal, Mark Woodward, and Xin-Hua Zhang. China: Fuwai Hospital and Cardiovascular Institute, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College: Dongfeng Gu (PI), Xigui Wu, Wenqi Gan, Shaoyong Su, Donghai Liu, Xiufang Duan, and Guangyong Huang. Beijing: Yifeng Ma, Xiu Liu, Zhongqi Tian, Xiaofei Wang, Guangyong Fan, Jiaqiang Wang, and Changlin Qiu. Fujian: Ling Yu, Xiaodong Pu, Xinsheng Bai, Linsen Li, and Wei Wu. Jilin: Lihua Xu, Jing Liu, Yuzhi Jiang, Yuhua Lan, Lijiang Huang, and Huaifeng Yin. Sichuan: Xianping Wu, Ying Deng, Jun He, Ningmei Zhang, and Xiaoyan Yang. Shandong: Xiangfu Chen, Renmin Wei, Xingzhong Liu, Huaiyu Ruan, Ming Li, and Changqing Zhang. Guangxi: Naying Chen, Xiaoyu Meng, Fangqing Wei, and Yongfang Xu. Qinghai: Tianyi Wu, Jianjiang Ji, Chaoxiu Shi, and Ping Yang. Hubei: Ligui Wang, Yuzhi Hu, Li Yan, and Yanjuan Wang. Jiangsu: Cailiang Yao, Liangcai Ma, Jun Zhang, Mingao Xu, and Zhengyuan Zhou. Shanxi: Jianjun Mu, Zhexun Wang, Huicang Li, and Zirui Zhao.

Human Participant Protection The institutional review board at the Tulane University Health Sciences Center approved the InterASIA study. In addition, ethics committees and other relevant regulatory bodies in China approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before data collection. During the study, participants with untreated conditions identified during the examination were referred to their usual primary health care provider.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors Dongfeng Gu participated in study design, data collection, and development. Xigui Wu, Xiufang Duan, and Xue Xin supervised data collection and quality control. Kristi Reynolds participated in data analysis and interpretation. Robert F. Reynolds and Paul K. Whelton participated in study design and interpretation of study findings. Jiang He participated in study design, supervised data collection and quality control, and wrote the article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Combating the tobacco epidemic. In: World Health Report 1999. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999.

- 2.Houston T, Kaufman NJ. Tobacco control in the 21st century. Searching for answers in a sea of change. JAMA. 2000;284:752–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackay J. Lessons from the conference: the next 25 years. In: Lu R, Mackay J, Nui S, Peto R, eds. The Growing Epidemic: Proceedings of the 10th World Conference on Tobacco or Health. Singapore: Springer; 1998.

- 4.Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, et al. Mortality from Smoking in Developed Countries 1950–2000. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994:103.

- 5.Yang G, Fan L, Tan J, et al. Smoking in China. Findings of the 1996 National Prevalence Survey. JAMA. 1999;282:1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan JM, Ross PK, Wang XL, Gao YT, Henderson BE, Yu MC. Morbidity and mortality in relation to cigarette smoking in Shanghai, China. JAMA. 1996;275:1646–1650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam TH, He Y, Li LS, He SF, Liang BQ. Mortality attributable to cigarette smoking in China. JAMA. 1997;278:1505–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen ZM, Xu Z, Collins R, Li WX, Peto R. Early health effects of the emerging tobacco epidemic in China. JAMA. 1997;278:1500–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu BQ, Peto R, Chen ZM, et al. Emerging tobacco hazards in China: 1. Retrospective proportional mortality study of one million deaths. BMJ. 1998;317:1411–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niu SR, Yang GH, Chen ZM, et al. Emerging tobacco hazards in China: 2. Early mortality results from a prospective study. BMJ. 1998:317:1423–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weng XZ, Hong ZG, Chen DY. Smoking prevalence in Chinese aged 15 and above. Chin Med J. 1987;100:886–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He J, Neal B, Gu D, et al. for the InterASIA Collaborative Group. International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia: Design, Rationale and Preliminary Results. Ethnicity Dis. 2004;14:260–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Health Statistics. Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–94. Vital and Health Statistics, series 1, No. 32. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 1994.

- 14.Pirkle JL, Flegal KM, Bernert JT, Brody DJ, Etzel RA, Maurer KR. Exposure of the US population to environmental tobacco smoke: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1991. JAMA. 1996;275:1233–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fellows JL, Trosclair A, Adams EK, Rivera CC. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Annual smoking attributable mortality, years of potential life lost and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999. JAMA. 2002;287:2355–2356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoenborn CA, Vickerie JL, Barnes PM. Cigarette smoking behavior of adults: United States, 1997–98. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 331. Hyattsville, MD; National Center for Health Statistics; 2003.

- 17.Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1999. MMWR. 2001;50:869–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Primatesta P, Falaschetti E, Gupta S, Marmot MG, Poulter NR. Association between smoking and blood pressure: evidence from the health survey for England. Hypertension. 2001;37:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins CN, Dai PX, Ngoc DH, et al. Tobacco use in Vietnam. Prevalence, predictors, and the role of the transnational tobacco corporations. JAMA. 1997;277:1726–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatsanavivat P, Klungboonkrong V, Chirawatkul A, et al. Prevalence of coronary heart disease and major cardiovascular risk factors in Thailand. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackshaw AK, Law MR, Wald NJ. The accumulated evidence on lung cancer and environmental tobacco smoke. BMJ. 1997;315:980–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He J, Vupputuri S, Allen K, Prerost MR, Hughes J, Whelton PK. Passive smoking and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:920–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong L, Goldberg MS, Gao YT, Jin F. A case-control study of lung cancer and environmental tobacco smoke among nonsmoking women living in Shanghai, China. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Lubin JH, Zhang SR, et al. Lung cancer and environmental tobacco smoke in a non-industrial area of China. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Y, Lam TH, Li LS, et al. Passive smoking at work as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in Chinese women who have never smoked. BMJ. 1994;308:380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]