Abstract

Objective. We evaluated the association between socioeconomic status and racial/ ethnic differences in endometrial cancer stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival.

Methods. We conducted a population-based study among 3656 women.

Results. Multivariate analyses showed that either race/ethnicity or income, but not both, was associated with advanced-stage disease. Age, stage at diagnosis, and income were independent predictors of hysterectomy. African American ethnicity, increased age, aggressive histology, poor tumor grade, and advanced-stage disease were associated with increased risk for death; higher income and hysterectomy were associated with decreased risk for death.

Conclusions. Lower income was associated with advanced-stage disease, lower likelihood of receiving a hysterectomy, and lower rates of survival. Earlier diagnosis and removal of barriers to optimal treatment among lower-socioeconomic status women will diminish racial/ethnic differences in endometrial cancer survival.

Cancer of the uterine corpus, of which 95% is classified as endometrial carcinoma,1,2 is the most common US female genital-tract malignancy. Although the age-adjusted incidence is 31% lower among African American women than among White women, the age-adjusted mortality among African American women is 84% higher.3 Moreover, the disparity in 5-year relative survival between African American and White women who had uterine corpus cancer (27% in the 1992–1997 cohort) was one of the largest observed in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.3

One important determinant of the racial/ ethnic difference in endometrial cancer survival is stage at diagnosis, where 40% of the survival difference is attributable to African American women who present with more advanced-stage disease.4 Advanced stage at diagnosis of endometrial cancer has been associated with increasing age, higher tumor grade, and more aggressive histology.5–9 However, after adjusting for these predictors, African American women are still more likely to present with advanced stage.2,5

The role of biological factors (e.g., more aggressive tumors) versus nonbiological factors (e.g., impediments to access to and utilization of quality medical care) in explaining racial/ ethnic differences in endometrial cancer stage at diagnosis and survival has been examined in several studies.4,5,8,10 Whether these racial/ ethnic differences reflect true biological variation or differences in lifestyle and sociocultural risk factors is not clear. In the United States, African Americans are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status (SES).11 Decreased access to or utilization of medical care among those who have lower SES can delay seeking treatment and thus result in greater risk for advanced-stage disease. Although delay in seeking treatment has not been shown to explain racial/ethnic differences in endometrial cancer stage at diagnosis,5,12–15 it has been shown that being poor, having no health insurance, and having no usual source of care are associated with lower medical-consultation rates.13 In univariate analyses, studies have shown several SES factors are associated with early-stage disease5,7; however, in the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Black/White cancer survival study, SES was not shown to have an independent association with endometrial cancer stage at diagnosis.4

Several studies have shown racial/ethnic differences in the availability of treatment options or the quality of cancer treatment.16 Among women who had advanced-stage en-dometrial cancer, White women were more likely than African American women to receive surgery and radiation therapy.10 In the NCI’s Black/White cancer survival study, substantially more White women had hysterectomies as their primary treatment than African American women did (95.4% vs 70.5%), and this racial/ethnic difference was apparent within each disease stage.4 SES differences may have contributed to these observed racial/ ethnic differences; however, this was not evaluated in the Bain et al. and NCI studies. The objective of our population-based retrospective cohort study was to evaluate the association between SES (measured at the aggregate census tract level) and racial/ethnic differences in stage at diagnosis, treatment received, and survival.

METHODS

Study Population and Eligibility

The study population was selected from the Detroit-area SEER cancer registry, a population-based registry of all incident cancers that occurred among residents of Ma-comb, Oakland, and Wayne counties in the state of Michigan. Registry data included information about demographics and tumor characteristics, first course of cancer-directed treatment, and time from diagnosis until death or last follow-up. African American and White women who were diagnosed with a primary cancer of the uterine corpus between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 1998, were eligible for our study; only women who had in situ cancers, uterine sarcomas, or a previous history of cancer other than basal or squamous cell carcinoma of the skin were excluded. The final study population of 3168 White and 488 African American women included all the eligible women.

We conducted a validation substudy to estimate the validity of ecologically assigned SES variables. This information was obtained from a separate project where all African American cases from 1998 and a randomly selected subset of White cases from 1998 were selected from the same registry on the basis of the same eligibility criteria. There were 107 women (27 African American and 80 White) who had information available for the validation substudy (response rate = 48.4%), which represented 26% of the eligible cases diagnosed in 1998. The women’s SES information was collected via telephone interviews or mailed questionnaires.

Measures

Outcome variables were stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Stage at diagnosis was classified as localized, regional, distant, or unstaged,17 and it was dichotomized as advanced stage (regional or distant) and not advanced stage (localized). Primary treatment via hysterectomy and/or radiation therapy was obtained from SEER records. Receipt of chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and immunotherapy was not evaluated, because SEER data are generally captured from hospital records and these treatments are frequently given outside the hospital setting. Survival time was measured from date of diagnosis to date of death. For patients who were still alive, data were censored on the basis of the date of last follow-up visit.

Tumor histology was classified in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology.18 Categories for less aggressive adenocarcinomas (endometrioid adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma) and more aggressive adenocarcinomas (clear cell adenocarcinoma, serous papillary adenocarcinoma, squamous carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma) also were created.1,19–21 Tumor grade was classified as well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, undifferentiated, and unknown.

SEER cancer registry data do not include individual-level SES information; however, each case’s registry data are geocoded to a census tract on the basis of residence at diagnosis. For our study, census tract was used to link each study case to census tract–level SES variables in the 1990 US Census of Population and Housing Summary Tape File 3A.22 The 3656 women in our study lived in 966 unique census tracts in the Detroit metropolitan area. Census tract information was missing for 17 women, who composed less than 0.5% of the study population.

Median census tract household income was ecologically assigned on the basis of residence at diagnosis after reported income was inflated to 1998 dollars with the consumer price index (CPI). For statistical analyses, we used the natural logarithm of median household income. Mean years of education was estimated by multiplying the race-specific number of individuals at each educational level by the midpoint of that level and then summing over all levels and dividing by the total. On the basis of previous studies of socioeconomic effects on health, we used a derived variable for “lives in an undereducated tract,” which was defined as women who lived in census tracts where 25% or more of the adults aged 25 years and older who were of the same race/ethnicity did not have a high school diploma.23

Statistical Methods

The validity of ecologically assigned SES variables was ascertained by comparing these variables with information obtained during the interview. The validity of mean years of education was evaluated with the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient. The validity of median household income, which was collapsed into the same categories obtained during the interview, was evaluated with the Spearman rank order correlation coefficient.

Differences in proportions were evaluated with the χ2 test; differences between means were evaluated with the t test. Survival was modeled with the Kaplan-Meier method, and racial/ethnic differences were evaluated with the log-rank test. Univariate associations were evaluated with the Wald χ2 test; parameters found to be significant (P < .05) were retained for multivariate analysis. Interactions that were found to be significant at the 10% level (Wald χ2) were retained for multivariate analyses, where stepwise logistic regression was used to evaluate advanced stage and treatment, and Cox proportional hazards regression was used to evaluate survival. The criteria for retaining variables were P < .05 for main effects and P < .10 for interactions. All analyses were 2-sided at a level of .05 and were performed with SAS software.24,25

RESULTS

Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are shown in Table 1 ▶. More than half the study population resided in Wayne County, and more than 90% of the African American women resided in Wayne County. The median age at diagnosis (65 years) did not differ between African American and White women. African American women were less likely to be married at the time of diagnosis than White women were.

TABLE 1—

Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Tumor-Related Characteristics Among African American and White Women Who Had Endometrial Cancer: Detroit, Mich, Tri-County Area, 1990–1998

| African American | White | Pa | |

| County, no. (%) | <.001 | ||

| Macomb | 7 (1.4) | 801 (25.3) | |

| Oakland | 35 (7.2) | 997 (31.5) | |

| Wayne | 446 (91.4) | 1370 (43.2) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean, y (SD) | 64.4 (12.8) | 64.1 (12.3) | .5662 |

| Aged < 65 y, no. (%) | 231 (47.3) | 1537 (48.5) | |

| Aged ≥ 65 y, no. (%) | 257 (52.7) | 1631 (51.5) | .627 |

| Marital status, no. (%) | <.001 | ||

| Single | 92 (18.9) | 340 (10.7) | |

| Married | 150 (30.7) | 1674 (52.8) | |

| Separated/divorced | 65 (13.3) | 236 (7.4) | |

| Widowed | 173 (35.5) | 876 (27.7) | |

| Unknown | 8 (1.6) | 42 (1.3) | |

| Education | |||

| Adults in tract with highest educational level in category shown, mean % (SD) | |||

| No high school diploma | 36.3 (13.75) | 20.8 (11.44) | <.0001 |

| High school diploma | 20.5 (6.81) | 30.2 (8.38) | <.0001 |

| Some college | 26.4 (9.06) | 26.9 (5.86) | .2226 |

| ≥ 4-year college degree | 10.0 (12.44) | 20.1 (15.49) | <.0001 |

| ≥ High school diploma | 62.7 (13.80) | 78.2 (11.44) | <.0001 |

| Lived in undereducated census tract,b no., (%) | 394 (81.4) | 1063 (33.7) | <.001 |

| Mean years education attained | |||

| Median | 11.4 | 12.5 | |

| Mean (SD) | 11.6 (1.13) | 12.6 (1.18) | <.0001 |

| Income | |||

| Median householdc | |||

| Median | 22,829 | 51,275 | |

| Mean (SD) | 27,008 (15,463.4) | 54,888 (22,149.5) | <.0001 |

| Lived in lowest income quartile,d no., (%) | 382 (78.3) | 541 (17.1) | <.001 |

| Histology, no. (%) | <.001 | ||

| Endometrioid | 350 (71.7) | 2844 (89.8) | |

| Clear cell | 27 (5.5) | 52 (1.6) | |

| Serous papillary | 69 (14.1) | 123 (3.9) | |

| Mucinous | 8 (1.6) | 59 (1.9) | |

| Undifferentiated | 16 (3.3) | 57 (1.8) | |

| Squamous | 10 (2.1) | 16 (0.5) | |

| Other | 8 (1.6) | 17 (0.5) | |

| Nonaggressive histology | 358 (74.6) | 2903 (92.1) | |

| Aggressive histology | 122 (25.4) | 248 (7.9) | <.001 |

| Stage of disease, no. (%) | <.001 | ||

| Localized | 267 (54.7) | 2303 (72.7) | |

| Regional | 109 (22.3) | 530 (16.7) | |

| Distant | 66 (13.5) | 254 (8.0) | |

| Unknown | 46 (9.4) | 81 (2.6) | |

| Not advanced | 267 (60.4) | 2303 (74.6) | |

| Advanced | 175 (39.6) | 784 (25.4) | <.001 |

| Tumor grade, no. N(%) | <.001 | ||

| Well differentiated | 108 (22.1) | 1447 (45.7) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 118 (24.2) | 905 (28.6) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 118 (24.2) | 410 (12.9) | |

| Undifferentiated | 49 (10.0) | 80 (2.5) | |

| Unknown | 95 (19.5) | 326 (10.3) | |

aMeans were compared using the t test; proportions were compared with the Mantel–Haenszel χ2 test.

b ≥25% in census tract did not have a high school diploma.

c Inflated to 1998 dollars in accordance with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) on the basis of the patient’s census tract at the time of diagnosis.

d Lowest quartile = $6613–$38 378 inflated to 1998 dollars in accordance with the CPI on the basis of the patient’s census tract at the time of diagnosis.

More than 80% of the African American women lived in undereducated tracts compared with only 34% of the White women (P = .001). Median household income among African American women was about half that among White women ($22 829 vs $51275, respectively; P = .0001). Notably, 78% of the African American women compared with 17% of the White women (P = .001) lived in census tracts where the median household incomes were in the lowest quartile.

Validation Substudy

The validation substudy found reasonably good correspondence26 between ecologically assigned income and self-reported income (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.52). The self-reported mean years of education was 13.4 (SD = 2.10), and the ecologically assigned mean years of education was 12.5 (SD = 1.13); the correlation of these 2 measures of education was weak (Pearson product moment correlation coefficient = 0.37).26 Because of the poor validity of ecologically assigned education, we did not include education in predictive models for stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival.

Stage at Diagnosis

African American women were significantly more likely to have aggressive endometrial cancer in terms of histology (P = .001) and tumor grade (P = .001) (Table 1 ▶). Among women who had known stage at diagnosis, approximately 40% of the African American women presented with advanced-stage disease compared with only 25% of the White women (P = .001).

In univariate analyses, the risk for African American women to present with advanced-stage disease was approximately twice that for White women (odds ratio [OR] = 1.93; 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.57, 2.37) (Table 2 ▶). Increasing age, aggressive histology, and poor tumor grade were associated with increased risk for advanced-stage disease, whereas higher family income was associated with decreased risk for advanced-stage disease. In multivariate analysis (stepwise logistic regression), after we adjusted for age, tumor grade, and histology, African American women were still 41% more likely to present with advanced-stage disease (P = .0079).

TABLE 2—

Variables Associated With Advanced-Stage Disease, Hysterectomy, and Risk for Death Among African American and White Women Who Had Endometrial Cancer: Detroit, Mich, Tri-County Area, 1990–1998

| OR or RRa | 95% CI | P | |

| Variables associated with advanced-stage disease | |||

| Univariate results | |||

| Race/ethnicity (African American vs White) | OR = 1.93 | 1.57, 2.37 | <.0001b |

| Age (5-year increase in age) | OR = 1.12 | 1.09, 1.16 | <.0001b |

| Histology (aggressive vs nonaggressive) | OR = 4.88 | 3.86, 6.16 | <.0001b |

| Tumor grade | OR = 5.19 | 4.29, 6.26 | <.0001b |

| Median family income | OR = 0.65 | 0.56, 0.76 | <.0001b |

| Multivariate results | |||

| Model selected: | <.0001c | ||

| Race/ethnicity (African American vs White) | OR = 1.41 | 1.09, 1.81 | .0079b |

| Age | OR = 1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 | .0073b |

| Tumor grade | OR = 4.28 | 3.52, 5.20 | <.0001b |

| Histology (aggressive vs nonaggressive) | OR = 2.62 | 1.93, 3.55 | <.0001b |

| Alternate model that forced income: | <.0001c | ||

| Median family income | OR = 0.83 | 0.69, 0.99 | .0456b |

| Age | OR = 1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 | .0123b |

| Tumor grade | OR = 4.31 | 3.55, 5.24 | <.0001b |

| Histology (aggressive vs nonaggressive) | OR = 2.73 | 2.02, 3.69 | <.0001b |

| Variables associated with hysterectomy | |||

| Univariate results for all stages of disease | |||

| Race/ethnicity (African American vs White) | OR = 0.39 | 0.30, 0.50 | <.0001b |

| Age (5-year increase in age) | OR = 0.77 | 0.73, 0.81 | <.0001b |

| Stage (advanced vs not advanced) | OR = 0.27 | 0.21, 0.34 | <.0001b |

| Median family income | OR = 2.16 | 1.77, 2.63 | <.0001b |

| Multivariate results for all stages of disease | |||

| Model selected: | <.0001c | ||

| Median family income | OR = 1.70 | 1.34, 2.15 | <.0001b |

| Age | OR = 0.95 | 0.94, 0.96 | <.0001b |

| Stage (advanced vs not advanced) | OR = 0.31 | 0.24, 0.40 | <.0001b |

| Univariate results for local stage | |||

| Race/ethnicity (African American vs White) | OR = 0.38 | 0.25, 0.59 | <.0001b |

| Age (5-year increase in age) | OR = 0.78 | 0.72, 0.85 | <.0001b |

| Median family income | OR = 2.27 | 1.64, 3.14 | <.0001b |

| Multivariate results for local stage | |||

| Model selected: | <.0001c | ||

| Median family income | OR = 2.13 | 1.53, 2.97 | <.0001b |

| Age | OR = 0.95 | 0.94, 0.97 | <.0001b |

| Variables associated with risk for death | |||

| Univariate results | |||

| Race/ethnicity (African American vs White) | RR = 2.33 | 1.75, 3.10 | <.0001b |

| Age | RR = 1.07 | 1.06, 1.07 | <.0001b |

| Histology (aggressive vs nonaggressive) | RR = 3.64 | 3.14, 4.21 | <.0001b |

| Tumor grade | RR = 2.84 | 2.44, 3.29 | <.0001b |

| Stage (advanced vs not advanced) | RR = 4.67 | 4.12, 5.30 | <.0001b |

| Median family income | RR = 0.51 | 0.45, 0.57 | <.0001b |

| Hysterectomy (yes vs no) | RR = 0.19 | 0.17, 0.22 | <.0001b |

| Multivariate results | |||

| Model selected: | <.0001c | ||

| Race/ethnicity (African American vs White) | RR = 1.73 | 1.26, 2.37 | .0007b |

| Age (in quartiles) | RR = 1.84 | 1.69, 2.01 | <.0001b |

| Histology (aggressive vs nonaggressive) | RR = 1.71 | 1.39, 2.09 | <.0001b |

| Stage (advanced vs not advanced) | RR = 4.74 | 3.72, 6.03 | <.0001b |

| Tumor grade | RR = 1.60 | 1.36, 1.88 | <.0001b |

| Median family income | RR = 0.80 | 0.68, 0.94 | .0065b |

| Hysterectomy (yes vs no) | RR = 0.23 | 0.19, 0.28 | <.0001b |

| Interaction between race/ethnicity and age | RR = 0.64 | 0.45, 0.91 | .0141b |

| Interaction between age and stage of disease | RR = 0.54 | 0.41, 0.71 | <.0001b |

Note. OR = odds ratio; RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval.

aORs derived from the logistic regression model; RRs derived from the Cox proportional hazards model.

bDerived from Wald χ2.

cDerived from score statistic.

On the basis of previous studies that showed collinearity of race with income,27 an alternate model was created to force median family income to be retained in the stepwise logistic regression model. With this model, race/ethnicity was no longer a significant independent predictor of advanced-stage disease, whereas higher median family income was inversely associated with advanced-stage disease (OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.69, 0.99). A third model was created to force both race/ ethnicity and median family income in the stepwise logistic regression model. When we used the likelihood ratio test, this third model was inferior to both the other models. Notably, estimates of the odds ratios for age, tumor grade, and histology remained consistent across the 3 models, which suggests it would be difficult to distinguish the independent contributions of race/ethnicity and income level to advanced-stage disease.

Because of the strong association between tumor biology and stage at diagnosis, we performed analyses stratified by “aggressive” and “nonaggressive” histology to determine the association between race/ethnicity and stage at diagnosis among these subgroups. Among women who had aggressive endometrial tumors, race/ethnicity (P = .8487), age (P = .1117), and median family income (P = .9224) were not associated with stage at diagnosis; only poor tumor grade was associated with advanced stage at diagnosis (OR = 13.37; 95% CI = 1.64, 108.87). However, among women who had endometrial tumors with nonaggressive histology, the results were nearly identical to those shown in Table 2 ▶. Similar to the multivariate analysis for the full study population, where either race or median family income, but not both, was independently associated with stage at diagnosis, the multivariate analysis of the subgroup of women who had nonaggressive endometrial tumors showed that either race or median family income, but not both, was associated with stage at diagnosis.

Treatment

The predominant treatment for endometrial cancer was hysterectomy—89.4% of all women received a hysterectomy as their first course of cancer-directed therapy (Table 3 ▶). When we controlled for stage at diagnosis, African American women were less likely to receive a hysterectomy (P = .001). This difference in hysterectomy was most pronounced among women who had localized disease, where 95.6% of the White women received a hysterectomy compared with 89.1% of the African American women (P = .001). The most common reason for not having a hysterectomy was “contraindicated/not recommended.” There was not a significant racial/ ethnic difference in reason for not having a hysterectomy; further analysis of reason for not having a hysterectomy was not performed because there was a lack of standard methods for recording these data in hospital records from which the data were abstracted.

TABLE 3—

Treatment for Endometrial Cancer Among African American and White Women Who Had Endometrial Cancer: Detroit, Mich, Tri-County Area, 1990–1998

| Total | African American | White | P | |

| Hysterectomy, no. (%) | 3270 (89.4) | 388 (79.5) | 2882 (91.0) | <.001a,b |

| Local stage | 2439 (94.9) | 238 (89.1) | 2201 (95.6) | <.001b |

| Regional stage | 568 (88.9) | 94 (86.2) | 474 (89.4) | .334b |

| Distant stage | 230 (71.9) | 45 (68.2) | 185 (72.8) | .455b |

| Unknown stage | 33 (26.0) | 11 (23.9) | 22 (27.2) | |

| No hysterectomy, no. (%) | 386 (10.6) | 100 (20.5) | 286 (9.0) | |

| Reason for no hysterectomy | .176b | |||

| Other surgery (e.g., biopsy, D&C) | 16 (4.2) | 6 (6.0) | 10 (3.5) | |

| Contraindicated/not recommended | 249 (64.5) | 58 (58.0) | 191 (66.8) | |

| Unknown reason | 50 (13.0) | 12 (12.0) | 38 (13.3) | |

| Refused | 36 (9.3) | 13 (13.0) | 23 (8.0) | |

| Planned | 31 (8.0) | 11 (11.0) | 20 (7.0) | |

| Unknown if performed | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Radiation Therapy, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 2503 (68.5) | 312 (63.9) | 2191 (69.3) | |

| Yes | 1149 (31.5) | 176 (36.1) | 973 (30.7) | .204b,c |

| Local stage | 621 (24.2) | 75 (28.1) | 546 (23.7) | .113b |

| Regional stage | 392 (61.3) | 68 (62.4) | 324 (61.1) | .807b |

| Distant stage | 106 (33.1) | 18 (27.3) | 88 (34.6) | .258b |

| Unknown stage | 30 (24.4) | 15 (32.6) | 15 (19.5) | .102b |

aFor hysterectomy vs no hysterectomy, after stage of disease was controlled.

bMantel–Haenszel χ2 test.

cFor radiotherapy vs no radiotherapy, after stage of disease was controlled.

In the univariate analyses, African American women were 61% less likely than White women to have a hysterectomy as primary treatment (OR = 0.39; 95% CI = 0.30, 0.50) (Table 2 ▶). In the multivariate analysis, women of increased age and women who presented with advanced-stage disease were less likely to receive a hysterectomy, whereas higher median household income was associated with increased likelihood of having a hysterectomy. Notably, race/ethnicity was not an independent predictor of hysterectomy in the multivariate analysis. Because hysterectomy is most frequently recommended for women who have local-stage disease, the analysis of predictors of hysterectomy was repeated among the subgroup of women who had local-stage disease only. The results were nearly identical (Table 2 ▶).

African American women were more likely than White women to receive radiation therapy (36.1% vs 30.7%) (Table 3 ▶). When we controlled for stage at diagnosis, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .204). When compared with White women, African American women who had local-stage disease tended to receive radiotherapy more frequently (28.1% vs 23.7%), yet African American women who had distant-stage disease tended to receive radiotherapy less frequently (27.3% vs 34.6%). These differences were not statistically significant.

Survival

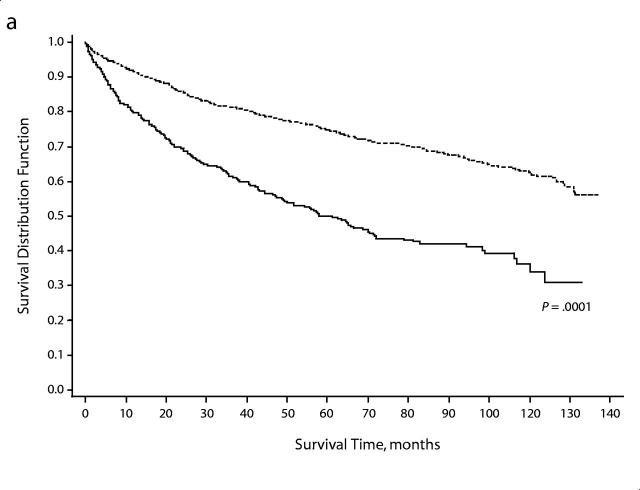

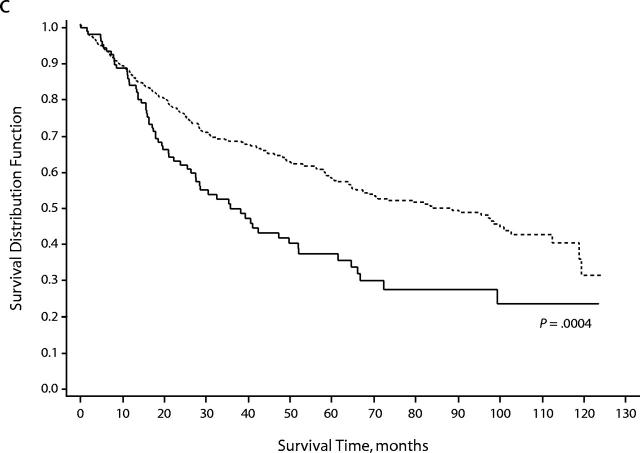

During the 9-year study period, 1066 (29.2%) women died. The proportion of African American women who died (233 women, 47.7%) was higher than that among White women (833 women, 26.3%) (P < .001). Overall survival time was shorter among African American women (Wilcoxon χ2 = 130.8, df = 1, P = 0.0001), and this racial/ethnic difference in survival time was apparent within each disease stage (Figure 1 ▶). The median survival time among African American women was 61.1 months (95% CI = 48.8–71.6 months); among White women, the median survival time was greater than 121 months, more than twice that for African American women.

FIGURE 1—

Survival, overall and by stage at diagnosis, among African American and White women who had endometrial cancer in the Detroit tri-county area, 1990–1998: (a) all stages combined, (b) local, (c) regional, (d) distant.

In general, older women (aged ≥ 65 years) had shorter survival time compared with younger women (aged < 65 years) (mean = 75.7 months vs 103.5 months; logrank P < .0001). African American women were more likely to die at younger ages ( < 65 years vs ≥ 65 years) compared with White women (32.6% vs 23.3%; P = .038), and the survival time among African American women was shorter than that among White women within each of these age strata (P < .001).

In the univariate analysis, African American women who had endometrial cancer were 2.33 times more likely to die than White women (P < .0001) (Table 2 ▶). In the best-fitting multivariate model, African American ethnicity, increased age, aggressive histology, advanced-stage disease, and poor tumor grade were independently associated with an increased risk for death, and higher median household income and having had a hysterectomy were independently associated with a decreased risk for death. Additionally, there were 2 significant interactions: advanced-stage disease was more strongly associated with increased risk for death among younger women (< 65 years) than among older women (≥ 65 years), and African American women had a higher risk for death at younger ages compared with White women.

Racial/ethnic differences in survival time also were evaluated by cause of death. For deaths caused by noncancer causes, there was a substantial racial/ethnic difference in survival time (median = 16.7 months among African American women vs 32.3 months among White women; logrank P = .0002). However, racial/ethnic differences in survival time were not observed for deaths caused by endometrial cancer (median survival = 14.2 months among African American women vs 14.7 months among White women; logrank P = .7953). The multivariate analysis was repeated among the subgroup of women who died as a result of endometrial cancer. Among this subgroup, increased age and advanced-stage disease were still associated with an increased risk for death, and having had a hysterectomy was still associated with decreased risk for death. Race/ethnicity was not associated with risk for death.

DISCUSSION

Among this population-based study group, higher median household income was associated with a decreased likelihood of presenting with advanced-stage disease, an increased likelihood of having had a hysterectomy as primary treatment, and a decreased risk for death. In the multivariate analyses, the results suggested that income level and race/ ethnicity were somewhat interchangeable when we examined differences in stage at diagnosis and treatment.

In the multivariate analysis, African American ethnicity and decreased median household income were associated with advanced-stage endometrial cancer independently but not simultaneously. When the analysis was stratified into subgroups of aggressive versus nonaggressive endometrial tumors, a notable pattern emerged: among women who had aggressive endometrial tumors, neither race/ ethnicity nor median family income was associated with stage at diagnosis, which suggests that sociocultural factors may not differentiate prognostic outcomes among women who had aggressive endometrial tumors. However, among women who had nonaggressive endometrial tumors, race/ ethnicity or median family income, but not both, was independently associated with stage at diagnosis. This finding suggests that race/ethnicity and SES similarly influence the risk for presenting with advanced-stage endometrial cancer among women who have nonaggressive endometrial cancer, who usually have an excellent prognosis when tumors are detected early.

Our study showed that higher income was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving a hysterectomy as the primary treatment for endometrial cancer. Although epidemiological studies of all-cause hysterectomies have shown that lower SES is associated with increased receipt of hysterectomy,28 only 11% of the hysterectomies in the United States are performed to treat uterine cancer.29,30 Variables such as age, race/ethnicity, geographic residence, and medical history31 also may influence whether hysterectomies are performed to treat women who have endometrial cancer. In the univariate analysis, African American women had a decreased likelihood of receiving a hysterectomy. This association was apparent even within the subgroup of women who had local-stage disease, where hysterectomy is usually recommended, and is consistent with findings from a recent literature review that found evidence of racial/ ethnic disparities in the receipt of definitive primary-cancer therapy.16 However, in our multivariate analysis, income, but not race/ ethnicity, was independently associated with having had a hysterectomy. Therefore, the racial/ethnic disparities in treatment for endometrial cancer may be mediated by differences in SES. Additionally, the prevalence of comorbid factors may represent contraindications to radical hysterectomy and may potentially confound the associations we found between treatment and race/ethnicity and SES. However, the availability of alternative options, such as vaginal hysterectomy with laparoscopic lymphadenectomy among medically compromised patients, emphasizes the importance of availability of quality medical care.32,33

When compared with White women, the African American women in our study had an increased risk for death after we controlled for aggressive tumor biology, advanced age, treatment, and income; this association was particularly apparent among younger African American women (P=0.0001). However, when survival was evaluated by cause of death, racial/ethnic differences were observed only among noncancer-related deaths. This result is different than that reported by Bach et al., where the risk for death caused by uterine cancer among African Americans was still twice that among Whites after they controlled for stage of disease, treatment, and other causes of mortality (hazard ratio = 2.08; 95% CI = 1.34, 3.21).34 Among women diagnosed with endometrial cancer, this might suggest that the racial/ethnic differences subsequently observed in survival are influenced by variables unrelated to endometrial cancer, including competing causes of mortality. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution because cause of death was not validated in our study.

A limitation to our study was the use of census data collected in 1990 for assigning SES variables to cases diagnosed between 1990 and 1998, thus allowing census data to be extrapolated over an 8-year period. However, a recent methodological study showed little impact when census data up to 10 years were used.27 Also, census block group data are preferable to the use of census tract data because the former minimizes heterogeneity in the unit of aggregation as a result of the smaller number of persons included in the aggregate.35 However, a recent methodological study showed little gain in accuracy when census block group data were used in place of census tract data.36

A major strength of our study was the generalizability that was a result of the large study population we obtained from a population-based registry that had complete ascertainment of cases. Very few data items were missing, and the registry provided a range of 2.7 to 10.6 years of follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

The relationship between SES and cancer survival is complex because SES has an impact on multiple risk factors associated with neoplastic transformation, progression, and death. Our study is unique in its examination of the impact of SES, independently of race/ ethnicity, among a geographically defined patient population that had endometrial cancer. Although age and tumor biology were strongly associated with prognosis, women at lower income levels were more likely to manifest advanced-stage disease, less likely to receive a hysterectomy as their primary treatment, and had poorer survival rates. Because of the strong association between SES and race/ethnicity, improving access to quality health care among low-SES women to facilitate earlier diagnosis and optimal treatment may serve to diminish the racial/ethnic difference in endometrial cancer survival.

Acknowledgments

Support for this manuscript was provided in part through a minority health statistics dissertation research grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (#T01/CCT517642–01) and the University of Michigan Cancer Center Munn Foundation. SEER registry grant support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (#N01-PC-65064).

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Wayne State University and the University of Michigan Medical School. Informed consent was obtained from each individual in the validation study, which was approved by both the Wayne State University Human Investigation Committee and the University of Michigan Medical School institutional review board.

Contributors T. Madison was responsible for originating the study, analyzing and interpreting the data, and writing the article. D. Schottenfeld, S. A. James, A. G. Schwartz, and S. B. Gruber assisted with originating the study and its design. All the authors originated ideas, interpreted results, and reviewed drafts of the article.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Shingleton HM, Fowler WC, Jordan JA, Lawrence WD. Gynecologic Oncology: Current Diagnosis and Treatment. London, UK: W.B. Saunders; 1996.

- 2.Platz CE, Benda JA. Female genital tract cancer. Cancer. 1995;75(Ssppl 1):270–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al., eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–1998. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute; 2001.

- 4.Hill HA, Eley JW, Harlan LC, Greenberg RS, Barrett RJ II, Chen VW. Racial differences in endometrial cancer survival: the black/white cancer survival study. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett RJ, Harlan LC, Wesley MN, et al. Endometrial cancer: stage at diagnosis and associated factors in black and white patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 173:414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madison TM, Schottenfeld D, Baker V. Cancer of the corpus uteri in white and black women in Michigan, 1985–1994: an analysis of trends in incidence and mortality and their relation to histologic subtype and stage. Cancer. 1998;83:1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill HA, Coates RJ, Austin H, et al. Racial differences in tumor grade among women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56:154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cronje HS, Fourie S, Doman MJ, Helms JB, Nel JT, Goedhals L. Racial differences in patients with adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1992;39:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aziz H, Hussain F, Edelman S, et al. Age and race as prognostic factors in endometrial carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1996;19:595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bain RP, Greenberg RS, Chung KC. Racial differences in survival of women with endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistical Abstract of the United States. 117th ed. Washington, DCS: US Bureau of the Census; 1997.

- 12.Liu JR, Conaway M, Rodriguez GC, Soper JT, Clarke-Pearson DL, Berchuck A. Relationship between race and interval to treatment in endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:486–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coates RJ, Click LA, Harlan LC, et al. Differences between black and white patients with cancer of the uterine corpus in interval from symptom recognition to initial medical consultation (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews RP, Hutchinson-Colas J, Maiman M, et al. Papillary serous and clear cell type lead to poor prognosis of endometrial carcinoma in black women. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirog EC, Heller DS, Westhoff C. Endometrial adenocarcinoma—lack of correlation between treatment delay and tumor stage. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;67: 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shavers V, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Nat’l Cancer Inst. 2002;94:334–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Cancer Institute. Summary Staging Guide, SEER Program. Bethesda, Md: National Institute of Health; 1981. NIH Publication No. 81.

- 18.International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 2nd edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1990.

- 19.Rose PG. Endometrial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:640–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoskins WJ, Perez CA, Young RC. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. Philadelphia, Pa: J. B. Lippincott; 1992.

- 21.World Health Organization. Histologic typing of female genital tract tumors. In: Scully RE, Bonfiglio TA, Kurman RJ, et al., eds. International Histologic Classification of Tumours. 2nd edition. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1994.

- 22.US Bureau of the Census. Census of Population and Housing, 1990. Summary Tape File 3 on CD-ROM [machine-readable data files]. Washington, DC:US Bureau of the Census; 1992.

- 23.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAS Language Reference, Version 6. 1st edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1990.

- 25.SAS Procedures Guide, Version 6. 3rd edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1990.

- 26.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geronimus AT, Bound J. Use of census-based aggregate variables to proxy for socioeconomic group: evidence from national samples. Am J Epidemiol. 1998; 148:475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjerulff K, Langenberg P, Guzinski G. The socioeconomic correlates of hysterectomies in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:106–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pokras R, Hufnagal VG. Hysterectomies in the United States, 1965–84. Vital Health Stat. 1987;92: 1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lepine LA, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, et al. Hysterectomy Surveillance—United States, 1980–1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer JR, Sowmya RR, Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L. Correlates of hysterectomy among African-American women. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150: 1309–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan JK, Lin YG, Monk BJ, Tewari K, Bloss JD, Berman ML. Vaginal hysterectomy as primary treatment of endometrial cancer in medically compromised women. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:707–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eltabbakh GH, Shamonki MI, Moody JM, Garafano LL. Hysterectomy for obese women with endometrial cancer: laparascopy or laparotomy? Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bach PB, Schrag D, Brawley OW, Galaznik A, Yakren S, Begg CB. Survival of blacks and whites after a cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2002;287:2106–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soobader M, LeClere FB, Hadden W, Maury B. Using aggregate geographic data to proxy individual socioeconomic status: does size matter? Am J Public Health. 2001;91:632–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]