Abstract

Group B Streptococcus (GBS; Streptococcus agalactiae) is an important cause of sepsis and meningitis. Nine GBS serotypes, based on capsular polysaccharide (CPS) antigens, have been described. Their distribution varies worldwide and needs to be monitored to understand the epidemiology of GBS disease and inform the development of vaccines. In this study, we sequenced cpsH of GBS serotype II (cpsHII) and compared it with that of the other eight serotypes to identify serotype-specific regions. We then developed a DNA microarray based on the cpsH gene and used it to test 88 GBS isolates—9 serotype reference strains and 79 clinical isolates—and 7 other bacterial and fungal species which are commonly present in the vagina flora. The microarray was shown to be specific and reproducible. This is the first report of a microarray which can identify the nine GBS serotypes. The use of a microarray has advantages over traditional serotyping methods and will be of practical value in both reference and diagnostic laboratories.

Group B Streptococcus (GBS; Streptococcus agalactiae) is an important cause of sepsis and meningitis in neonates and infants and of invasive disease in pregnant women, nonpregnant, presumably immunocompromised adults, and the elderly (8, 22). Capsular polysaccharide (CPS) is external to the gram-positive bacterial cell wall and enables the bacterium to evade host immune defenses. CPS is essential to the virulence of GBS, and serotype-specific antibody is protective. Therefore, it is the target for most experimental GBS vaccines. Nine distinct CPS serotypes (Ia, Ib, and II to VIII) have been described (12, 13), and their distribution varies worldwide. For example, serotypes Ia and III have been reported to be the predominant ones in the maternal genital tract in the United States (2, 7), China (23), Germany (9), and Australia and New Zealand (16). In Korea, serotype Ib is most common (25), and in Japan serotypes VI and VIII are predominant among GBS isolated from pregnant women (18). Epidemiological studies of GBS are important for the development of GBS vaccines that are suitable for all geographic areas. Therefore, a convenient and rapid method to identify all nine GBS serotypes would be useful.

Many GBS serotyping methods have been reported previously, including immunoprecipitation (26), enzyme immunoassay (14), coagglutination (11), counterimmunoelectrophoresis and capillary precipitation (24), latex agglutination (27), fluorescence microscopy (6), and inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (1), and antisera are necessary for most of these methods. Commercial antisera are expensive and available for only six serotypes (Ia to V), which does not satisfy the needs of traditional serotyping methods (1). Moreover, serotyping is often subjective, and a significant proportion of isolates are nontypeable. Molecular typing methods, such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (20) and restriction endonuclease analysis (19), have also been used for epidemiological studies, but they do not directly identify serotypes and are generally time-consuming and expensive.

A previous report, based on analysis of cpsH in GBS serotypes Ia and III (3), suggested that cpsH, which encodes CPS polymerases, was serotype specific in bacteria which produce complex polysaccharides. We have developed a molecular serotyping method based on PCR and sequencing of various genes in the cps cluster, including cpsH, which has been recently adapted to a more practicable multiplex PCR and reverse line blot assay format, targeting serotype-specific sequences (16a). Sequences of cpsH for all GBS serotypes have been deposited in GenBank (see Table 2). Sequence alignment shows that the cpsHII (GenBank accession number AY375362) and cpsHIII (AF363056) sequences are identical, which is inconsistent with the different CPS structures of these two serotypes (4, 17). Therefore, we sequenced another cpsHII strain in preparation for this study, in which we developed a DNA microarray, based on serotype-specific sequences of cpsH, for identification of all GBS serotypes.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer name | Gene | Tm (°C) | GenBank accession no. | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wl-4432 | cfba | 42.5 | X72754 | 328-GATGTATCTATCTGGAACTCTAGTG-352 |

| wl-4433 | cfb | 48.4 | X72754 | 568-TTTTTCCACGCTAGTAATAGCCTC-545 |

| wl-4347 | cpsGIa-VIIb | 49.5 | AF363060 | 2126-GAACCTCAGAATTGTCAGTGGTCA-2149 |

| wl-4596 | cpsHIa | 49.5 | AF363060 | 3381- ATTATTTATAACGATGTTTACTGTA-3357 |

| wl-4597 | cpsHIb | 63.1 | AB050723 | 3718-AGGTCGAATGCGATCCTAGTGG-3697 |

| wl-4598 | cpsHII | 52.7 | DQ234264 | 896-CTTAGTGCAAGTGTTGAAGAATA-874 |

| wl-4599 | cpsHIII | 60.5 | AF363056 | 3015-TTGGGGTTTCAAAAAAAGTATGG-2993 |

| wl-4600 | cpsHIV | 49 | AF355776 | 7831-CAACTACATTGACTTTTTTACTAT-7808 |

| wl-4601 | cpsHV | 51.4 | AF349539 | 7459-ATAATACCCTGTCCTTGAAAA-7439 |

| wl-4602 | cpsHVI | 53.9 | AF337958 | 7840-TACTAATGTATGATGAATGTGAACC-7816 |

| wl-4603 | cpsHVII | 48.1 | AY376403 | 4820-GTTCAACTATTCTTATTTCTTTAC-4797 |

| wl-4604 | cpsHVIIIc | 51.6 | AY375363 | 4615-GGTGCCACTTCTTTAGGTT-4633 |

| wl-4605 | cpsHVIII | 50.9 | AY375363 | 5840-TCACAAATCGCTTCTTCAT-5822 |

The cfb gene is a housekeeping gene which encodes cyclic AMP, which is used as the positive control of GBS.

The universal upload primer of types Ia to VII was designed in the cpsG gene. The N-terminal regions of this gene in all nine serotypes expect serotype VIII share a high level of identity.

The upload primer of GBS type VIII was designed in the cpsHVIII gene.

DNA microarray is a newly developed technology used for the detection of pathogens and is rapid and sensitive. It consists of four steps: extraction of genomic DNA, amplification of targeted DNA, hybridization of labeled DNA with oligonucleotide probes immobilized on a microarray, and results analysis. We believe it has significant advantages over other methods for routine serotyping of GBS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Nine GBS reference strains, 79 GBS clinical isolates, which were isolated in different countries between 1994 and 2001, and isolates of 7 other bacterial and fungal species, namely, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii, and Candida albicans, were used in this study (Table 1). All of the GBS isolates had been previously characterized by conventional and molecular serotyping (MS) as previously described (15).

TABLE 1.

Isolates used in this study

| Strain type or name | No. of strains | Strain description or geographic origin |

|---|---|---|

| GBS reference strains (n = 9) | ||

| Ia | 1 | O90 (Rockefeller University)a |

| Ib | 1 | H36B (ATCC 12401; NCTC 8187)a |

| II | 1 | 18 RS 21 (NCTC 11079)a |

| III | 1 | M 781 (ATCC BAA-22)a |

| IV | 1 | 3139a |

| V | 1 | CJB 111 (ATCC BAA-23)a |

| VI | 1 | SS 1214a |

| VII | 1 | 7271a |

| VIII | 1 | JM9 130013a |

| Clinical GBS isolates of known serotype used to test the microarray (n = 51) | ||

| Ia | 9 | Australiab (n = 6); New Zealandc (n = 3) |

| Ib | 7 | Australiab (n = 2); New Zealandc (n = 5) |

| III | 21 | Australiab (n = 11); New Zealandc (n = 10) |

| IV | 4 | Australiab (n = 2); New Zealandc (n = 2) |

| V | 7 | Australiab (n = 3); New Zealandc (n = 4) |

| VI | 1 | Australiab |

| VII | 3 | Australiad (n = 2); Japana (n = 1) |

| Clinical GBS isolates used for blind testing of the microarray (n = 28) | ||

| IV | 6 | Hong Konge; South Koreaf; New Zealandc |

| III | 10 | United Kingdomg |

| II | 7 | United Kingdomg; Hong Konge |

| VII | 4 | United Kingdomg; Australiad |

| V | 1 | United Kingdomg |

| Species used to test the specificity of the microarray (n = 7) | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | Chinah |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1 | Chinah |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 | Australiab |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | Australiai |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | 1 | Chinaj |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii | 1 | Chinaj |

| Candida albicans | 1 | Chinak |

Obtained from Channing Laboratory, Boston, Mass.

Obtained from the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology laboratory services (CIDM), Sydney, Australia.

Obtained from the Streptococcus Reference Laboratory, ESR, Wellington, New Zealand.

Obtained from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Melbourne, Australia.

Obtained from the Department of Microbiology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong.

Obtained from the Research Institute of Bacterial Resistance, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea.

Obtained from the Nuffield Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, Institute for Molecular Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Obtained from the National Institute for The Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products, CMCC, Beijing, People's Republic of China.

Obtained from the University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

Obtained from the Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, People's Republic of China.

Obtained from the Institute of Dermatology, Peking Union Medical College & Chinese Academy of Medical Science, Nanjing, People's Republic of China.

The GBS isolates were inoculated into Todd-Hewitt broth (10.0 g/liter beef heart infusion, 20.0 g/liter tryptone, 2.0 g/liter glucose, 2.0 g/liter sodium bicarbonate, 2.0 g/liter sodium chloride, 0.4 g/liter disodium phosphate [pH 7.8 ± 0.2]) and incubated overnight at 37°C.

Sequence analysis.

Sequencing of cpsHII was carried out using an ABI 3730 automated DNA sequencer. Two primers, wl-3401 (5′-GATTGTTATCACACATGGC-3′) and wl-3402 (3′-ATATATTTTTTTCA/GTAA/TTAACC-5′), were used to amplify the gene, and the amplicon is 1,881 bp. The sequence data used in this study for cpsH of other serotypes were obtained from GenBank with the following accession numbers: AF332905, AF332906, AF363037, AF363044, AF363045, AF363053, AF363054, and AY375362. Sequence alignment and comparisons of cpsH sequences of all nine GBS serotypes were performed using the ClustalW program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw). The phylogenetic tree was generated using Mega 3.

Serotype II-specific PCR.

Because of differences between our cpsHII sequence and the one available in GenBank (accession number AY375362), we designed three serotype II-specific primer pairs based on our sequence and two pairs based on the original sequence. We then tested the 10 serotype II strains in our collection by PCR and identified the products by gel electrophoresis. Primer sequences are shown in Table 2.

Genomic DNA extraction.

Genomic DNA extraction was performed as follows. Overnight broth cultures (1.5 ml) were centrifuged for 10 min at 3,000 × g. The deposit was resuspended in 500 μl of SET (75 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.5]). Lysozyme (50 mg/ml) was added to the tube, and after incubation at 37°C for 2 h, 1/3 volumes of 5 M NaCl, 1/10 volumes of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K were added. Tubes were incubated at 55°C with occasional inversion for 2 h, then 1 volume of chloroform was added, and the tubes were centrifuged at 4,500 × g for 15 min twice to purify the DNA. The resulting supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and 1 volume of isopropanol was added. Tubes were held at −20°C for 20 min and then centrifuged at 4,500 × g for 10 min. The aqueous phase was discarded, and the remaining contents were rinsed with 70% ethanol and dried at 37°C. Purified DNA was dissolved in 30 μl Tris-EDTA and stored at −20°C.

Multiplex PCR.

Based on analysis of cpsH sequences of all nine serotypes, primer pairs suitable for multiplex PCR were designed. From 69 primers initially tested, 13 were chosen (Table 2) based on testing of 60 GBS isolates (9 serotype reference strains and 51 clinical isolates [Table 1]). These 13 primers include a universal forward primer for serotypes Ia to VII targeting cpsG, which apparently encodes N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase (21) and is conserved in all serotypes except VIII (4). The forward primer for serotype VIII targets cpsHVIII. Serotype-specific reverse primers were designed for each of the nine serotypes as well as a pair of primers targeting the GBS species-specific gene cfb. The PCR products range from 240 bp to 1,310 bp in length.

For multiplex PCR, DNA was prepared as above, and 50 to 100 ng was used as a template in a final volume of 50 μl of PCR mixture containing the following: 1× PCR buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]); 0.5 mM MgCl2; 200 μM concentrations of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 42 nM each of two primers based on the cfb gene (housekeeping gene of GBS); 140 nM each of 11 other primers; and 0.03 U Taq DNA polymerase. The PCR cycle was performed with the initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and concluding with a cycle of 72°C for 10 min.

Labeling of the targeted DNA.

For labeling of PCR products, multiplex PCR mixtures contained 1× PCR buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]); 0.8 mM MgCl2; 334 μM concentrations of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 187 nM each of 10 reverse primers; 0.25 nM cyanine dye Cy3-dUTP; and 0.05 U Taq DNA polymerase complemented to a final volume of 30 μl with amplified multiplex PCR products from the above amplification step. The PCR cycle was performed with the initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 95°C, annealing for 45 s at 50°C, and extension for 1 min at 72°C, and cycling was concluded with a final elongation for 10 min at 72°C. All labeled DNA was purified in refining tubes (Millipore Co.) and then stored at −20°C in the dark.

Oligonucleotide probe set and microarray construction.

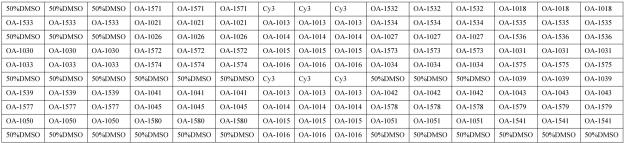

Probes used in this study were designed using Oligoarray 2.0 and synthesized with a 5′ amidocyanogen modifier, and 15 poly(T) oligonucleotides were added. From 178 probes tested, 35 were selected based on preliminary testing of 60 GBS strains representing all serotypes (Table 3). Glass slides, modified by an aldehyde group, were purchased from CEL Corporation. There are four arrays on each glass slide. The construction of a single array and the meaning of each spot are shown in Fig. 1. Oligonucleotide probes were diluted in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide to a final concentration of 1 μg/μl and spotted onto the slides using SpotArray 7.2 (Perkin Elmer Corporation). Each probe was duplicated three times. Printed slides were dried for 24 h at room temperature. In order to immobilize probes, slides were treated with a UV Cross-linker (UVP Corporation) and then stored at room temperature.

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide probes used in this study

| Probe no. | Targeted gene | Tm (°C) | GenBank accession no. | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA-1013 | cfb | 79.28 | X72754 | 355-TGGTGCATTGTTATTTTCACCAGCTGTATTAGAAGTAC-392 |

| OA-1014 | cfb | 79.99 | X72754 | 373-ACCAGCTGTATTAGAAGTACATGCTGATCAAGTGAC-408 |

| OA-1015 | cfb | 80 | X72754 | 397-TGATCAAGTGACAACTCCACAAGTGGTAAATCATGTAA-434 |

| OA-1016 | cfb | 80.1 | X72754 | 456-AAATGGCTCAAAAGCTTGATCAAGATAGCATTCAGTTG-493 |

| OA-1571 | cpsHIa | 79.55 | AF363060 | 2935-GGTAGAGATTTGATTGGGTCAGACTGGATTAATGGTAT-2972 |

| OA-1532 | cpsHIa | 81.46 | AF363060 | 3143-GGGCTGGAATAGTAGCTATATTGGCGCAGATGTTTATT-3180 |

| OA-1018 | cpsHIa | 80.15 | AF363060 | 3301-CGTATAATTAATTTGCGATCCGGGAGTAGTGAATCCAG-3338 |

| OA-1533 | cpsHIb | 78.85 | AB050723 | 2985-ATTTAGAAGTCCAGAATTTCATAGAGTCATTGCTGCA-3021 |

| OA-1021 | cpsHIb | 79.68 | AB050723 | 3395-GGTCTGGATCTAGAGCTGGTATTATAGTTGTGCTACTA-3432 |

| OA-1534 | cpsHIb | 78.73 | AB050723 | 3582-GTCGGGAAGTAGTGAATCTAGATTTTCTTTGTACAAGG-3619 |

| OA-1535 | cpsHIb | 78.84 | AB050723 | 3621-TACCGTACACTCAGTAATTACTGACTCACTATTTCTGG-3658 |

| OA-1026 | cpsHII | 80.57 | DQ234264 | 411-AGTAGTAGCAAGGTATGCGTATGGATTTAATCATCCCA-448 |

| OA-1027 | cpsHII | 78.93 | DQ234264 | 663-AATAGCACCGTATGTACAGTTTATTGCGATGTTTAGTT-700 |

| OA-1536 | cpsHII | 78.19 | DQ234264 | 763-AGTGGTAGAATTTATTACGCGAAGCTTATCTTAACAGA-800 |

| OA-1030 | cpsHIII | 79.7 | AF363056 | 2863-CCTATGCTGAAGCCAACTTTATTTGGAAGAGAATTGTT-2900 |

| OA-1572 | cpsHIII | 78.77 | AF363056 | 2886-TGGAAGAGAATTGTTTTCAATAGAGTGGTTTCCACATA-2923 |

| OA-1573 | cpsHIII | 81.32 | AF363056 | 2906-TAGAGTGGTTTCCACATATGAGAATAAGACTTGCGGC-2942 |

| OA-1031 | cpsHIII | 80.35 | AF363056 | 2911-TGGTTTCCACATATGAGAATAAGACTTGCGGCATATTT-2948 |

| OA-1033 | cpsHIV | 79.98 | AF355776 | 7543-ATAGTTGCTCCGTACATACAACTGTTCTTGTTAGCATT-7580 |

| OA-1574 | cpsHIV | 80.05 | AF355776 | 7545-AGTTGCTCCGTACATACAACTGTTCTTGTTAGCATTTA-7582 |

| OA-1034 | cpsHIV | 79.28 | AF355776 | 7549-GCTCCGTACATACAACTGTTCTTGTTAGCATTTACTTT-7586 |

| OA-1575 | cpsHIV | 78.95 | AF355776 | 7633-GATAGCCTTTTGACAGGTAGGTTAAACTATGCTCATTT-7670 |

| OA-1039 | cpsHV | 78.68 | AF349539 | 7362-TACTCAATTATAAACGACTAAAGCCTGTTGTGATGGTT-7399 |

| OA-1539 | cpsHVI | 78.23 | AF337958 | 7344-TGAATGGATTCCTTCTATGAAAGTTAGACTTACTGCAT-7381 |

| OA-1041 | cpsHVI | 80.22 | AF337958 | 7496-GTGCATATTTGACAGGGGCAAGAATTTTCCTAATTTGT-7533 |

| OA-1042 | cpsHVI | 80.3 | AF337958 | 7742-TAAGAGCGATTTTAGATGGGAATTTCCTTATTGGGCAA-7779 |

| OA-1043 | cpsHVI | 80.17 | AF337958 | 7764-TTTCCTTATTGGGCAAGGTATAAGAGTTCCCTCC-7797 |

| OA-1577 | cpsHVII | 78.72 | AY376403 | 4045-AAGAAAACTCGTTACTATCTTCTTGTTATTTGTCGCGA-4082 |

| OA-1045 | cpsHVII | 78.95 | AY376403 | 4047-GAAAACTCGTTACTATCTTCTTGTTATTTGTCGCGACT-4084 |

| OA-1578 | cpsHVII | 78.34 | AY376403 | 4049-AAACTCGTTACTATCTTCTTGTTATTTGTCGCGACTAT-4086 |

| OA-1579 | cpsHVII | 78.34 | AY376403 | 4051-ACTCGTTACTATCTTCTTGTTATTTGTCGCGACTATTT-4088 |

| OA-1050 | cpsHVIII | 80.1 | AY375363 | 5237-TAGTGATTATCCCATTATTGATGTCGGCAACTGTTGAG-5274 |

| OA-1580 | cpsHVIII | 80.41 | AY375363 | 5241-GATTATCCCATTATTGATGTCGGCAACTGTTGAGAACT-5278 |

| OA-1051 | cpsHVIII | 80.43 | AY375363 | 5247-CCCATTATTGATGTCGGCAACTGTTGAGAACTATATCG-5284 |

| OA-1541 | cpsHVIII | 78.61 | AY375363 | 5258-TGTCGGCAACTGTTGAGAACTATATCGTAAATGTAAAT-5295 |

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the microarray, showing positions of immobilized probes spotted within a single well of the four-well glass slides. Each array contains 150 spots arranged in 15 columns. Cy3 is a fluorescent dye. Sequences of probes immobilized at each location are shown in Table 3.

DNA microarray hybridization.

The purified product was baked for 90 min at 65°C in a dry oven, diluted in 12 μl hybridization buffer (25% formamide, 0.1% SDS, 6× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA {pH 7.7}]) and hybridized for 16 h at 40°C. After hybridization, the chip was rinsed in solution A (1× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% SDS) for 3 min, solution B (0.05× SSC) for 3 min, and solution C (95% ethanol) for 1.5 min. The chip was then dried, in the dark, at room temperature.

Signal detection and data analysis.

The hybridized microarray was scanned with a 532-nm laser beam using the biochip scanner LuxScan-10K/A (Capitalbio Corporation) using the following parameters: laser intensity, 80%; photomultiplier tube gain, 70%; scan resolution, 5 nm.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence of cpsHII has been deposited in GenBank under the accession number DQ234264.

RESULTS

Sequencing and analysis of cpsHII.

The sequence we obtained for cpsHII from the GBS serotype II reference strain (Table 1) was significantly different from that previously deposited in GenBank (accession number AY375362). All 10 GBS serotype II strains tested by PCR produced amplicons of the expected length with primers (wl-4184, 5′-ATACAGGTGTTTACAGGGAC-3′; wl-4185, 3′-GATAAATAGATGGCAAAGAA-5′; wl-4186, 5′-TAGGGAGTAGGAAGATAGC-3′; wl-4187, 3′-TAACGCTACAAATCAAACA-5′; wl-4184, 5′-ATACAGGTGTTTACAGGGAC-3′; and wl-4188, 3′-GCTTTCAATCACGTCCTAGT-5′) based on the new sequence but not with those based on the original sequence. These results confirm that the original sequence of cpsHII was incorrect.

Analysis of cpsH sequences of all nine GBS serotypes.

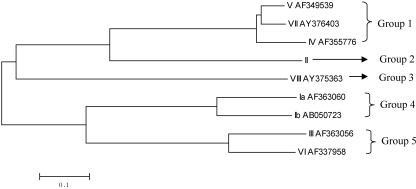

Sequence alignment of cpsH sequences of all nine GBS serotypes showed that they fell into five groups (Fig. 2), each consisting of one to three sequences, which is consistent with CPS structural data (4). The three cpsH sequences in group 1 shared 85.5 to 91% identity, and the two sequences in groups 4 and 5 shared 75% and 76.7% identity, respectively. Despite the similarities between cpsH sequences within groups, we were able to identify serotype-specific regions, which could be probed to differentiate these closely related serotypes. Therefore, cpsH appears to be an appropriately variable, serotype-specific region within the cps gene cluster for use as the targeted gene for differentiation of GBS serotypes.

FIG. 2.

A phylogenetic tree generated based on cpsH of all nine GBS serotypes by the neighbor-joining method.

Optimization of multiplex PCR.

Initially, we used the same concentration (140 nM) for all 13 primers, but we could not consistently achieve expected signals after hybridization for some serotypes. The multiplex PCR products were tested by gel electrophoresis, which showed that only some of the targeted serotype sequences which produce long fragments were amplified. Therefore, we tested various proportions of the primers which produce amplicons of short and long fragments in ratios of 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4. By repeating hybridization and gel electrophoresis, we found that expected signals were achieved consistently when the ratio of primers producing short fragments to primers producing long fragments was approximately 1:3.

Specificity.

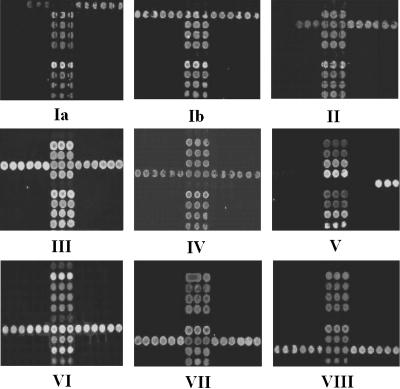

The DNA microarray was tested initially using 60 GBS isolates, including 9 serotype reference strains and 51 clinical isolates of known serotype, mainly from Australia and New Zealand (Table 1). Through 242 hybridization reactions, 35 specific probes and 13 primers were selected for use in the microarray. The microarray identified all 60 GBS isolates correctly when results were compared with those of our MS method (15) (Fig. 3), and it gave negative results for all 7 isolates of other bacterial and fungal species likely to be present in the vagina or to cause bacteremia (Table 3).

FIG. 3.

Representative hybridization results of GBS strains of nine serotypes. The number under each array shows the serotype of GBS tested. Three lines of dots located in the middle of the array are positive controls based on cfb of GBS.

Double-blind test.

Twenty-eight clinical isolates (shown in Table 1) were randomly selected from all strains which were stored in the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology for double-blind testing in order to prove the stability and veracity of the GBS DNA microarray. After hybridization, we found that 7 isolates are serotype II, 10 isolates are serotype III, 6 isolates are serotype IV, 1 isolate is serotype V, and 4 isolates are serotype VII, which is consistent with MS results.

DISCUSSION

Optimization of multiplex PCR.

We found that not only melting temperatures (Tm) and cross-dimer formation between primer pairs but also the concentrations of individual primers in the reaction mixture affected the success of the multiplex PCR. A ratio of 1:3 of primers producing short fragments to primers producing long fragments gave optimal results, probably because primers producing short fragments consume reagents, such as deoxynucleoside triphosphate and Taq DNA polymerase, preferentially unless present in a lower concentration.

Two-step multiplex PCR was used in this study. The first step ran without labeling, and the second one ran with labeling. Although this test format prolongs the time of detection, it has many advantages. First, two-step PCR can amplify more amplicons, which enhance the hybridization signal, and in the meantime make the microarray method more sensitive. In addition, if the amplification and labeling of target DNA are finished at the same time, the labeled target DNA must be denatured before hybridization, and the denatured DNA must always be annealed, which would reduce the amount of single-stranded DNA. To avoid such situations, two-step multiplex PCR was selected. In the second step, we used only downstream primers, which produce single-stranded labeled target DNA directly.

Hybridization.

The final sets of probes and primers were selected according to the following criteria: the probes were in the amplified region and specific to their corresponding serotype, and there was no significant cross-dimer formation between members of primer pairs. Although the probes and primers were designed to be specific, repeated hybridization was needed to select the best primers and probes for the DNA microarray.

According to a previous report, 15 poly(T) was the best spacer length to ensure high-quality hybridization results (10). All probes on this DNA microarray have approximately the same Tm values and GC contents. There is no obvious relationship between probe length and consistency of hybridization, and probes of the same length do not necessarily hybridize under the same conditions. On the other hand, we found that probes with relatively similar GC contents and Tm hybridize consistently under similar conditions. Furthermore, sometimes short labeled single-stranded amplicons are more difficult to hybridize with corresponding probes than the larger ones. This phenomenon is infrequent and may be due to the secondary structure of DNA.

Practicability.

We tested the specificity and reproducibility of the microarray with GBS isolates of unknown (at the time of testing) serotype and other bacterial and fungal species likely to be encountered in similar clinical specimens. The results confirmed that cpsH is a suitable gene to identify GBS serotypes and that our GBS DNA microarray, the first of its kind to be described, is a practicable and reliable tool for routine identification and serotyping of GBS.

According to the 2002 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, all pregnant women should be screened for GBS at 35 to 37 weeks of pregnancy (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5111a1.htm). In this study, we did not compare the sensitivity of our method with conventional culture methods for direct detection of GBS. However, we believe that its use for routine screening of vaginal secretions of pregnant women, either directly or after preliminary enrichment, would be feasible. This requires further evaluation. This DNA microarray will certainly be useful for testing GBS isolates in studies of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of GBS infection and vaccine research.

It would be useful to add probes for surface protein antigens to the microarray. A multiplex PCR assay has been reported to identify GBS proteins (5). In the future it should be practicable to combine multiplex PCR with the DNA microarray to identify both capsular polysaccharide and protein antigens simultaneously.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NSFC Key Program (30530010) and funds from the Science and Technology Committee of Tianjin City (05YFGZGX04700) to L.W. and L.F.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakere, G., A. E. Flores, P. Ferrieri, and C. E. Frasch. 1999. Inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serotyping of group B streptococcal isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2564-2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumberg, H. M., D. S. Stephens, C. Licitra, N. Pigott, R. Facklam, B. Swaminathan, and I. K. Wachsmuth. 1992. Molecular epidemiology of group B streptococcal infections: use of restriction endonuclease analysis of chromosomal DNA and DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms of ribosomal RNA genes (ribotyping). J. Infect. Dis. 166:574-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaffin, D. O., S. B. Beres, H. H. Yim, and C. E. Rubens. 2000. The serotype of type Ia and III group B streptococci is determined by the polymerase gene within the polycistronic capsule operon. J. Bacteriol. 182:4466-4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cieslewicz, M. J., D. Chaffin, G. Glusman, D. Kasper, A. Madan, S. Rodrigues, J. Fahey, M. R. Wessels, and C. E. Rubens. 2005. Structural and genetic diversity of group B Streptococcus capsular polysaccharides. Infect. Immun. 73:3096-3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creti, R., F. Fabretti, G. Orefici, and C. von Hunolstein. 2004. Multiplex PCR assay for direct identification of group B streptococcal alpha-protein-like protein genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1326-1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cropp, C. B., R. A. Zimmerman, J. Jelinkova, A. H. Auernheimer, R. A. Bolin, and B. C. Wyrick. 1974. Serotyping of group B streptococci by slide agglutination fluorescence microscopy, and microimmunodiffusion. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 84:594-603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards, M. S. 1990. Group B streptococcal infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 9:778-781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farley, M. M. 2001. Group B streptococcal disease in nonpregnant adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:556-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fluegge, K., S. Supper, A. Siedler, and R. Berner. 2005. Serotype distribution of invasive group B streptococcal isolates in infants: results from a nationwide active laboratory surveillance study over 2 years in Germany. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:760-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo, Z., R. A. Guilfoyle, A. J. Thiel, R. Wang, and L. M. Smith. 1994. Direct fluorescence analysis of genetic polymorphisms by hybridization with oligonucleotide arrays on glass supports. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:5456-5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakansson, S., L. G. Burman, J. Henrichsen, and S. E. Holm. 1992. Novel coagglutination method for serotyping group B streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:3268-3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison, L. H., J. A. Elliott, D. M. Dwyer, J. P. Libonati, P. Ferrieri, L. Billmann, A. Schuchat, and Maryland Emerging Infections Program. 1998. Serotype distribution of invasive group B streptococcal isolates in Maryland: implications for vaccine formulation. J. Infect. Dis. 177:998-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hickman, M. E., M. A. Rench, P. Ferrieri, and C. J. Baker. 1999. Changing epidemiology of group B streptococcal colonization. Pediatrics 104:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holm, S. E., and S. Hakansson. 1988. A simple and sensitive enzyme immunoassay for determination of soluble type-specific polysaccharide from group B streptococci. J. Immunol. Methods 106:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong, F., S. Gowan, D. Martin, G. James, and G. L. Gilbert. 2002. Serotype identification of group B streptococci by PCR and sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:216-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong, F., D. Martin, G. James, and G. L. Gilbert. 2003. Towards a genotyping system for Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus): use of mobile genetic elements in Australasian invasive isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:337-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Kong, F., L. Ma, and G. L. Gilbert. 2005. Simultaneous detection and serotype identification of Streptococcus agalactiae using multiplex PCR and reverse line blot hybridization. J. Med. Microbiol. 54:1133-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuypers, J. M., L. M. Heggen, and C. E. Rubens. 1989. Molecular analysis of a region of the group B streptococcus chromosome involved in type III capsule expression. Infect. Immun. 57:3058-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lachenauer, C. S., D. L. Kasper, J. Shimada, Y. Ichiman, H. Ohtsuka, M. Kaku, L. C. Paoletti, P. Ferrieri, and L. C. Madoff. 1999. Serotypes VI and VIII predominate among group B streptococci isolated from pregnant Japanese women. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1030-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagano, Y., N. Nagano, S. Takahashi, K. Murono, K. Fujita, F. Taguchi, and Y. Okuwaki. 1991. Restriction endonuclease digest patterns of chromosomal DNA from group B beta-haemolytic streptococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 35:297-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolland, K., C. Marois, V. Siquier, B. Cattier, and R. Quentin. 1999. Genetic features of Streptococcus agalactiae strains causing severe neonatal infections, as revealed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and hylB gene analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1892-1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubens, C. E., R. F. Haft, and M. R. Wessels. 1995. Characterization of the capsular polysaccharide genes of group B streptococci. Dev. Biol. Stand. 85:237-244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuchat, A. 1999. Group B streptococcus. Lancet 353:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen, A., Y. Zhu, G. Zhang, Y. Yang, and Z. Jiang. 1998. Experimental study on distribution of serotypes and antimicrobial patterns of group B streptococcus strains. Chin. Med. J. (Engl. Ed.) 111:615-618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Triscott, M. X., and G. H. Davis. 1979. A comparison of four methods for the serotyping of group B streptococci. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 57:521-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uh, Y., I. H. Jang, K. J. Yoon, C. H. Lee, J. Y. Kwon, and M. C. Kim. 1997. Colonization rates and serotypes of group B streptococci isolated from pregnant women in a Korean tertiary hospital. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:753-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkinson, H. W., and M. D. Moody. 1969. Serological relationships of type I antigens of group B streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 97:629-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuerlein, T. J., B. Christensen, and R. T. Hall. 1991. Latex agglutination detection of group-B streptococcal inoculum in urine. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14:191-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]