Abstract

In this study, we performed fliC PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) to investigate whether this technique would be better than classic serotyping for the characterization of the H antigen in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains. We showed that the fliC genes from ETEC strains can be characterized by restriction analysis of their polymorphism. Only one allele of the fliC gene from ETEC strains was found for each flagellar antigen, with the exception of H21. Nonmotile strains could also be characterized using this molecular technique. Moreover, determination of the somatic antigen was guided by the identification of the flagellar antigen from previously unknown serotypes of ETEC strains by PCR-RFLP, thus reducing the number of anti-antigen O sera used. The PCR-RFLP technique proved to be faster than classic serotyping for the characterization of the E. coli H antigen, taking 2 days to complete instead of the 7 or more days using classic serotyping. In conclusion, the H molecular typing for Enterobacteriaceae members may become an important epidemiological tool for the characterization of the H antigen of E. coli pathotypes. The PCR-RFLP technique is capable of guiding the determination of the H antigen and could partially replace seroagglutination. With the determination of the molecular profiles of alleles from strains obtained in epidemiological studies, new patterns will be described for ETEC strains or other E. coli pathotypes, thus permitting widespread use of this technique to characterize fliC genes and determine the H antigen of E. coli strains.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) remains a major cause of infantile diarrhea in the developing world as well as an agent of travelers' diarrhea in visitors to these areas (8, 17). ETEC secretes two major protein enterotoxins that induce fluid and electrolyte secretion by enterocytes and express fimbrial (or fibrillar) colonization factor antigens that function as adhesins and promote their attachment to the small intestinal epithelium (16).

E. coli is a clonal species, and characterization of the cell surface lipopolysaccharide O antigen and the flagellar H antigen allow the grouping of pathogenic clones within this species. E. coli has 187 O and 53 H antigens defined by serology (4). Although a great variety of O serogroups was identified in ETEC, O6, O8, O78, O128, and O153 are the most common antigens. Considerably fewer H than O antigens are associated with ETEC, and H7, H12, H16, H21, H45, and H49 are the most common. Some of them are strongly associated with an O serogroup, namely, O27:H7, O8:H9, O78:H12, O128:H12, O6:H16, O148:H28, O25:H42, and O153:H45 (16). Because of these associations, determination of the O antigen can be guided by the identification of the flagellar H antigen among ETEC strains. This is important, because identification of a particular H antigen would reduce the amount of time and the number of antisera required to identify the O antigen in ETEC strains.

Analysis of nucleic acid biomarkers for the detection and identification of bacteria has become widespread since the development of the necessary molecular biological tools. In particular, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis has been used for the identification of various infectious bacteria. The structure of the ETEC flagellin (H antigen) gene (fliC), with terminal conserved regions, makes it an ideal candidate for PCR amplification, which can be combined with RFLP to target variation in the central region. The conserved sequences at each end of this gene allow the amplification of a wide range of alleles with a single set of primers (15).

Fields et al. (5) developed a PCR-RFLP test to identify and characterize the fliC gene. They showed that the restriction analysis of this gene can be used to type both O157:H7 and O157:H− Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Moreover, they demonstrated that almost all the other 52 flagellar antigens investigated in their study had distinct fliC RFLP patterns after restriction with RsaI. Such distinct patterns could therefore be used to identify the respective H antigens. This method has been shown to be an important tool for the detection of bacteria, for the determination of genetic relationships, and for epidemiological studies (1, 2, 3, 5, 9, 11, 13, 18).

In the present study, we applied the fliC RFLP method to characterize fliC genes from 128 ETEC strains and 53 H antigen E. coli reference strains. We showed that the H antigen of ETEC can be characterized by restriction analysis of the polymorphism of the fliC gene by using the restriction endonuclease RsaI. As a result, an identification scheme is proposed to deduce H antigen groups.

The fliC-RFLP technique proved to be faster than classic serotyping for the deduction of the E. coli H antigen, taking 2 days to complete instead of the 7 or more days when using classic serotyping.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The E. coli H antigen reference strains were obtained from the E. coli Reference Laboratory, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, or from the Adolfo Lutz Institute, São Paulo, Brazil (Table 1). The 128 clinical ETEC strains (91 motile and 37 nonmotile strains) belonged to the ETEC collection of B. E. C. Guth at the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, and are summarized in Table 2 and 3. The ETEC strains were isolated from sporadic diarrhea cases in different periods of time. Thus, they are not likely to be closely related. The O and H antigens were determined by standard procedures (4) at the time of isolation of the ETEC strains, using antisera (O1-O171; H1-H56) kindly provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

TABLE 1.

fliC gene restriction analysis of E. coli reference strains using RsaI

| H antigen reference strain | O antigen | Molecular pattern | fliC fragment size(s) (bp) | Restriction fragment(s) (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | O6 | P1 | 1,790 | 740, 420, 290, 170, 140 |

| H2 | O3 | P2 | 1,500 | 550, 400, 310, 160, 120 |

| H3 | O53 | P3 | 1,620 | 390, 340, 300, 290, 160, 150 |

| H4 | O2 | P4 | 1,500 | 490, 290 |

| H5 | O4 | P5 | 1,300 | 1300 |

| H6 | O120 | P6 | 1,590 | 510, 410, 320, 220, 150 |

| H7 | O1 | P7 | 1,760 | 410, 350, 310, 230, 210, 140, 130 |

| H8 | O105 | P8 | 1,500 | 710, 320, 290, 170, 150 |

| H9 | O130 | P9 | 1,970 | 1,120, 310, 300, 160 |

| H10 | O108 | P10 | 1,190 | 520, 330, 310 |

| H11 | O26 | P11 | 1,500 | 540, 280, 170, 150, 130 |

| H12 | O9 | P1 | 1,790 | 740, 420, 290, 170, 140 |

| H14 | O138 | P12 | 1,560 | 610, 560, 420 |

| H15 | O23 | P13 | 1,590 | 440, 320, 280, 220 |

| H16 | O46 | P3 | 1,620 | 390, 340, 300, 290, 160, 150 |

| H17 | O15 | —a | — | — |

| H18 | O17 | P14 | 1,680 | 760, 560, 200, 110 |

| H19 | O32 | P15 | 1,720 | 590, 410, 280, 240, 200 |

| H20 | O126 | P16 | 1,690 | 380, 310, 290, 220, 190 |

| H21 | O8 | P17 | 1,560 | 380, 320, 290, 280, 170, 150 |

| H23 | O158 | P18 | 1,620 | 480, 290, 270, 200, 130 |

| H24 | O51 | P19 | 1,480 | 370, 320, 290, 280, 160, 140 |

| H25 | O86 | P20 | 1,360 | 930, 300 |

| H26 | O38 | P21 | 1,510 | 520, 3020, 140 |

| H27 | O58 | P11 | 1,500 | 540, 280, 170, 150, 130 |

| H28 | O148 | P22 | 1,540 | 400, 310, 180, 150 |

| H29 | O133 | P23 | 1,190 | 380, 330, 300, 170, 100 |

| H30 | O86 | P24 | 1,490 | 550, 390, 300, 290, 90 |

| H31 | O73 | P25 | 1,470, 500 | 540, 420, 390, 220, 170 |

| H32 | O114 | P26 | 1,720 | 750, 520, 320, 120 |

| H33 | O11 | P27 | 1,500 | 640, 400 |

| H34 | O164 | P28 | 1,420 | 620, 510, 390 |

| H35 | O14 | P29 | 1,260 | 540, 390, 320, 300 |

| H36 | O86 | P30 | 2,600 | 680, 540, 280, 210, 140, 100 |

| H37 | O42 | P31 | 1,360 | 820, 310, 220, 130, 110 |

| H38 | O69 | P32 | 1,250 | 310, 180, 160, 150, 140, 110 |

| H39 | O74 | P33 | 1,490 | 320, 280, 270, 210 |

| H40 | O41 | P34 | 1,380 | 290, 250, 160 |

| H41 | O137 | P35 | 1,490 | 620, 490, 260, 200 |

| H42 | O70 | P36 | 1,300 | 620, 330, 310 |

| H43 | O140 | P37 | 1,420 | 400, 360, 310, 300, 130 |

| H44 | O3 | P38 | 1,640, 900 | 720, 600, 500, 330, 300, 210, 130 |

| H45 | NT | P39 | 1,680 | 420, 370, 300, 200, 130, 110, 80 |

| H46 | O115 | P40 | 1,580 | 460, 310, 270, 240, 190, 110 |

| H47 | O156 | P41 | 1,290 | 550, 280, 170, 150 |

| H48 | O16 | P42 | 1,300 | 600, 460, 280, 80 |

| H49 | O6 | P43 | 1,500 | 420, 310, 290, 260, 210, 130 |

| H51 | O132 | P44 | 1,600 | 350, 290, 250, 230, 200, 140, 130, 100 |

| H52 | O11 | P45 | 1,130 | 690, 370, 170 |

| H53 | O148 | — | — | — |

| H54 | NT | — | — | — |

| H55 | O4 | P5 | 1,300 | 1,300 |

| H56 | O26 | P46 | 1,300 | 910, 300, 100 |

—, not amplified by PCR.

TABLE 2.

fliC gene restriction analysis of motile ETEC strains using RsaI

| H antigen | Serogroup (no. of strains) | Molecular pattern | fliC fragment size (bp) | Restriction fragments (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Ra (1) | P2 | 1,500 | 550, 400, 310, 160, 120 |

| H7 | O27 (4) | P7a | 1,760 | 540, 500, 350, 230, |

| O128 (4) | 130 | |||

| H8 | R (1) | P8 | 1,500 | 710, 320, 290, 170, |

| Oundb (2) | 150 | |||

| H9 | Ound (2) | P9 | 1,970 | 1,120, 310, 300, 160 |

| O8 (3) | ||||

| R (1) | ||||

| H12 | O78 (10) | P1 | 1,790 | 740, 420, 290, 170, |

| O128 (10) | 140 | |||

| Ound (1) | ||||

| H16 | O6 (14) | P3 | 1,620 | 390, 340, 300, 290, |

| O23 (2) | 160, 150 | |||

| H18 | Ound (2) | P14 | 1,680 | 760, 560, 200, 110 |

| H19 | O62 (1) | P15a | 1,980 | 630, 590, 280, 240 |

| O109 (1) | ||||

| H21 | O9 (2) | P17 | 1,560 | 380, 320, 290, 280, |

| O29 (4) | 170, 150 | |||

| O128 (3) | ||||

| H21 | O60 (2) | P17a | 1,560 | 380, 320, 290, 230, 170, 150 |

| H21 | O114 (1) | P17b | 1,580 | 380, 320, 290, 260, |

| O159 (2) | 170, 150 | |||

| H25 | O88 (3) | P20 | 1,360 | 930, 300 |

| Ound (1) | ||||

| H27 | O128 (2) | P11 | 1,500 | 540 280, 170, 150, 130 |

| H32 | O8 (1) | P26 | 1,720 | 750, 520, 320, 120 |

| H42 | O25 (2) | P36 | 1,300 | 620, 330, 310 |

| Ound (1) | ||||

| H45 | O153 (3) | P39 | 1,680 | 420, 370, 300, 200, |

| O159 (1) | 130, 110, 80 | |||

| Ound (1) |

R, rugose strains.

Ound, O undetermined by typing sera.

TABLE 3.

fliC gene restriction analysis of nonmotile ETEC strains using RsaI

| Nonmotile strain | Serogroup (no. of strains) | Molecular pattern (correspondent serotype) | Restriction fragment(s) (bp) | fliC fragment size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM-a | O27 (4) | P16 (H20) | 380, 310, 290, 220, 190 | 1,690 |

| NM-b | O16 (1) | P10 (H10) | 520, 330, 310 | 1,190 |

| O88 (1) | ||||

| O112 (1) | ||||

| Ounda (1) | ||||

| NM-c | Ound (1) | P5 (H5, H55) | 1,300 | 1,300 |

| NM-d | Ound (1) | P47b | 600, 390, 360, 340, 310, 300, 280, 230, 200 | 4,170 |

| O64 (1) | ||||

| O154 (3) | ||||

| NM-e | O114 (1) | P43 (H49) | 420, 310, 290, 260, 210, 130 | 1,500 |

| Rc (1) | ||||

| NM-f | O104 (1) | P48b | ||

| Ound (3) | ||||

| NM-g | Ound (1) | P24 (H30) | 550, 390, 300, 290, 90 | 1,500 |

| NM-h | Ound (1) | P34 (H40) | 290, 250, 160 | 1,380 |

| NM-i | Ound (1) | P1 (H1 or H12) | 740, 420, 290, 170, 140 | 1,790 |

| NM-j | O6 (1) | P3 (H3 or H16) | 390, 340, 300, 290, 160, 150 | 1,620 |

| O21 (1) | ||||

| O23 (1) | ||||

| O25 (1) | ||||

| NM-k | O77 (1) | P14 (H18) | 760, 560, 200, 110 | 1,680 |

| NM-l | Ound (1) | P15 (H19) | 630, 590, 280, 240 | 1,980 |

| NM-m | O128 (2) | P17a (H21) | 380, 320, 290, 230, 170, 150 | 1,560 |

| NM-n | O88 (1) | P20 (H25) | 930, 300 | 1,360 |

| NM-o | O86 (1) | P26 (H32) | 750, 520, 320, 120 | 1,720 |

Ound, O undetermined by typing sera.

No matching molecular pattern.

R, rugose strains.

DNA extraction.

A single colony was grown in 3 ml of Luria-Bertani broth medium overnight at 37°C under static culture. Genomic DNA was obtained using the Easy DNA kit (Invitrogen, Brazil).

fliC PCR-RFLP analysis.

The PCR-RFLP protocol developed by Fields et al. (5) was performed with slight modifications. We used the same primers (F-FLIC1 and R-FLIC2) as Botelho et al. (2) and Fields et al. (5), who have confirmed (by sequencing and/or hybridization) that the amplified fragments were indeed the fliC gene. PCR was performed in the GeneAmp PCR system 2400 (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a reaction volume of 100 μl containing approximately 84 ng of DNA, 0.3 M of each primer, 50 M (each) deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate, 10 μl of 10-fold-concentrated polymerase synthesis buffer, 2 mM of MgCl2, and 6.66 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, São Paulo, Brazil). The PCR conditions included denaturation for 30 s at 95°C, annealing for 60 s at 60°C, and extension for 120 s at 72°C for 35 cycles. Fifteen microliters of each PCR product was digested with RsaI restriction enzyme according to the manufacturer's instructions. Digestion with HhaI endonuclease was further employed in cases where no differentiation was obtained with RsaI. Restriction fragments were separated on a 3% (wt/vol) agarose gel for 3 h at 8 V/cm and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. A 100-bp DNA ladder (Invitrogen, São Paulo, Brazil) was used as an external fragment size standard.

Determination of DNA fragment size and identification of flagellar type.

Digitization and interpretation of patterns were done using the Photodocumentation System DP-001.FDC, version 10 (Vilber Lourmat, Marne-la-Vallée Cedex 1, France), and PhotoCapt MW, version 10.01, for Windows. In pattern comparisons, the base pair-tolerated variation (allowed error) was set to fragments 5 bp in size, meaning that two fragments were considered identical when their sizes did not differ by more than 5 bp.

Serotyping.

Serotyping was performed by standard procedures (4). Antisera against E. coli H antigens were obtained from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, and ETEC strains were serotyped at the Federal University of São Paulo. Antisera to E. coli somatic antigens O1 to O170 were obtained from the E. coli Reference Laboratory, Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

RESULTS

fliC-RFLP analysis of E. coli H reference strains.

To investigate the ability of the PCR-RFLP method to differentiate the fliC alleles that encode the various H antigens, E. coli reference strains H1 to H56 were subjected to fliC-RFLP analysis. This analysis was performed repeatedly (three times or more) for each strain studied. The flagellin gene was amplified in 50 of the 53 strains tested. Most E. coli strains tested produced a single band ranging from approximately 1,130 to 2,600 bp; the exceptions were the H31 and H44 strains, which amplified a second band (Table 1). The fliC gene was not amplified in the H17, H53, and H54 strains, even under different PCR conditions, thus indicating inadequate primer homology. Following digestion with RsaI, most fliC amplification products displayed distinct restriction patterns. A common pattern was observed for the fliC gene from the H1 and H12 strains (P1), the H3 and H16 strains (P3), the H5 and H55 strains (P5), and the H11 and H27 strains (P11). To further characterize these eight alleles, we performed RFLP with HhaI endonuclease. The fliC genes that encoded the H1, H11, H12, and H27 antigens were differentiated by HhaI restriction analysis. However, the H3 and H16 strains and H5 and H55 strains were also indistinguishable when the PCR fragments were restricted with HhaI (Table 4). It is important to notice that these H antigens can present cross-reactions during classic serotyping because they share common epitopes. The fliC-RFLP analysis of E. coli H reference strains was performed in order to determine the profile of those antigens and compare them with the other profiles obtained in this study. The majority of H antigens could be differentiated by PCR-RFLP, allowing us to continue our investigation.

TABLE 4.

fliC gene restriction analysis of H1, H3, H5, H11, H12, H16, H27, and H55 reference strains using HhaI

| Reference strain | Molecular patterns | fliC fragment size (bp) | Restriction fragments (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | P1/A | 1,790 | 680, 400, 220, 170, 130, 90, 70 |

| H12 | P1/B | 1,790 | 630, 390, 220, 170, 110, 80, 60 |

| H3 | P3/A | 1,620 | 1,330, 1,200, 1,070, 220, 140, 70 |

| H16 | P3/A | 1,620 | 1,330, 1,200, 1,070, 220, 140, 70 |

| H5 | P5/A | 1,300 | 850, 770, 710, 210, 110, 90, 60 |

| H55 | P5/A | 1,300 | 850, 770, 710, 210, 110, 90, 60 |

| H11 | P11/A | 1,500 | 450, 430, 300, 230 |

| H27 | P11/B | 1,500 | 380, 310, 300, 230, 150 |

PCR amplification of the ETEC fliC gene.

The flagellin gene was amplified in 122 of the 128 strains tested (88 motile strains and 34 nonmotile strains). Single bands ranging from 1,300 to 1,980 bp for motile strains (Table 2) and from 1,190 to 4,170 bp for nonmotile strains (Table 3) were obtained. The fliC gene was not amplified in six strains belonging to serotypes O159:H4 (two strains), NT:H25, O19:NM, O38:NM, and NT:NM, even under different PCR conditions, thus indicating inadequate primer homology or an absence of the gene.

RFLP patterns of the fliC gene of motile ETEC serotypes.

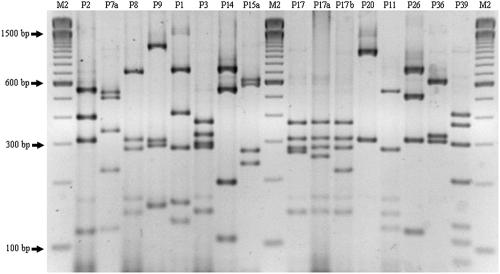

To investigate the fliC-RFLP patterns of different ETEC isolates, 88 motile strains of 14 different H types (Table 2) were subjected to PCR with primers F-FLIC1 and R-FLIC2 and subsequent restriction with RsaI. Table 2 and Fig. 1 show the RFLP patterns for each H-type studied. The H21 strains showed three different specific patterns (P17, P17a, and P17b). In contrast, all other strains showed a single and specific restriction pattern. The P17 pattern was predominant among the H21 types. The pattern (P15a) observed for the fliC from both H19 ETEC strains was different from the pattern (P15) obtained for the fliC from the H19 reference strain. Using RFLP analysis of the fliC gene from motile ETEC strains, we were able to distinguish all the H antigens studied. We found that different alleles can encode the same H antigen, as was the case for the H21 and H19 antigens. However, most H antigens studied for ETEC presented only one allele.

FIG. 1.

Electrophoretic separation (on a 3% agarose gel) of RsaI RFLP fragments of the fliC gene from motile ETEC strains belonging to 16 different H types. All alleles presented distinct electrophoretic profiles. M2, 100-bp ladder (Invitrogen); P2, pattern of allele from serotype H2; P7a, serotype H7; P8, serotype H8; P9, serotype H9; P1, serotype H12; P3, serotype H16; P14, serotype H18; P15a, serotype H19; P17, serotype H21; P17a, serotype H21; P17b, serotype H21; P20, serotype H25; P11, serotype H27; P26, serotype H32; P36, serotype H42; and P39, serotype H45.

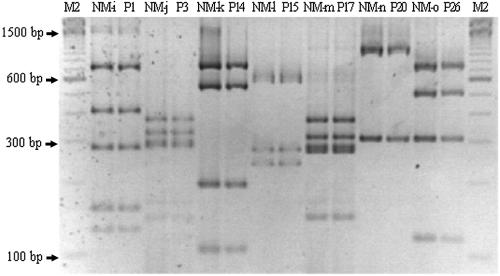

RFLP patterns of the fliC gene from nonmotile ETEC serotypes.

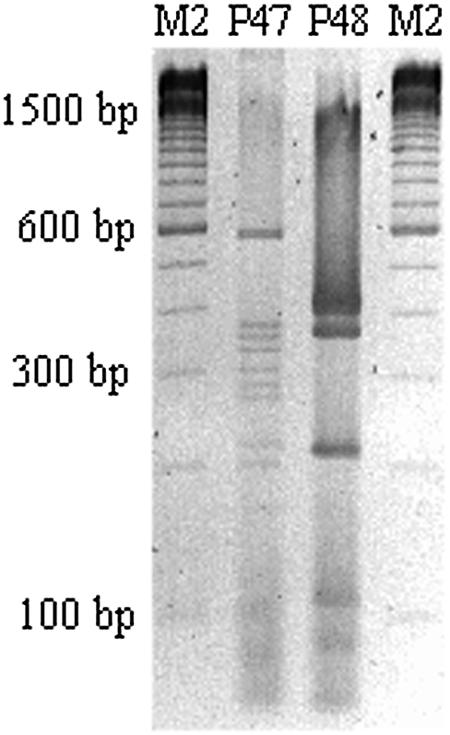

Table 3 shows the patterns presented by 34 nonmotile strains. A total of 15 different patterns were observed after RsaI restriction. Thirteen patterns were identical to some of those observed for H reference strains or H motile ETEC strains (Fig. 2). In nine nonmotile strains, there were no patterns comparable to those from ETEC motile strains or E. coli reference strains. The nine nonmotile strains with nonmatching patterns were in serogroups NT (one strain), O64 (one strain), and O154 (three strains), sharing the P47 pattern, and serogroups O104 (one strain) and NT (three strains), sharing the P48 pattern (Fig. 3). The fliC gene from these strains probably is encoded by rare alleles. Two strains belonging to the nontypeable O serogroup did not present any RsaI sites, but they showed indistinguishable patterns when fliC was restricted with HhaI. However, we were able to characterize those alleles because they shared patterns (P5/A) with the H5 and H55 reference strains (Table 4) with HhaI. The fliC-RFLP analysis proved to be an efficient molecular tool for the characterization of fliC genes from nonmotile ETEC strains. Nonmotile strains cannot be analyzed by classic serotyping of E. coli H antigens, because these strains have a cryptic fliC gene and are not able to express the H antigen. Thus, PCR-RFLP represents an alternative method to characterize nonmotile strains.

FIG. 2.

Representative RFLP patterns (on a 3% agarose gel) of fliC gene matches of motile ETEC and nonmotile ETEC isolates using RsaI. Unlike serotyping, which only enables characterization of motile strains, the RFLP method allows the characterization of the fliC alleles present but not expressed in nonmotile strains. M2, 100-bp ladder (Invitrogen); NM-I, NT:NM; P1, O128:H12; NM-j, O6:NM and O23:NM; P3, O6:H16; NM-k, O77:NM; P14, NT:H18; NM-l, R:NM; P15, O62:H19; NM-m, O128:NM; P17, O128:H21; NM-n, O88:NM; P20, O88:H25; NM-o, O86:NM; P26, O8:H32.

FIG. 3.

Two RFLP profiles on a 3% agarose gel that do not match with the RFLP patterns of the fliC of the reference strains. Nevertheless, we were able to characterize two alleles from nine nonmotile ETEC strains which were not previously known. M2, 100-bp ladder (Invitrogen); P47, NM-d (NT:NM, O64:NM, O154:NM); P48, NM-f (NT:NM, O104:NM).

Analysis of discrepant results between H serotypes and fliC-RFLP patterns.

H serotyping is the gold standard method for the determination of H antigens. However, there are difficulties associated with conventional H serotyping, as cross-reactions occur between particular H antigens that share common epitopes. During our study, four strains presented discrepant results between their H types and the fliC-RFLP patterns (Table 5). Thus, we observed the same fliC-RFLP profile for different H antigens that do not present cross-reactions in classic serotyping. This could imply that PCR-RFLP is not an efficient molecular tool for the characterization of the fliC gene. Therefore, to dispel this notion, we performed a new H serotyping to confirm the H antigen from those strains. All strains, during the reagglutination assays, reacted with the expected antisera after analysis of RFLP patterns. These results reinforce the notion that fliC-RFLP analysis is a reliable and efficient method for the characterization of the fliC gene from ETEC strains.

TABLE 5.

Characteristics of ETEC strains that showed discrepancies between H antigen and fliC RFLP patterns

| Previous serotype | fliC RFLP pattern, matching serotype | New serotype |

|---|---|---|

| O159:H21 | P39, H45 | O159:H45 |

| O128:H27 | P7, H7 | O128:H7 |

| Ound:H4a | P36, H42 | Ound:H42 |

| R:H27b | P9, H9 | R:H9 |

Ound, O undetermined by typing sera.

R, rugose strains.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the H antigen from ETEC strains can be characterized by PCR-RFLP of the fliC gene, allowing the differentiation of flagellar antigen groups. The restriction enzyme RsaI was chosen based on work by Fields et al. (5). Only one allele of the fliC gene from ETEC strains was found for each flagellar antigen, with the exception of H21, which showed genetic diversity.

The high diversity of restriction profiles was attributed to variability within an internal region of the flagellin genes, whereas regions at the 5′ and 3′ ends are more conserved (6). Joys (7) suggested that random mutations accumulated in the central region of the fliC gene due to an absence of functional constraints. The alternative view is that selection pressure and lateral gene transfer provide a source of variation (11, 14). The mammalian host immune system is the driving force for continuous selection of new flagellar antigens in E. coli.

In most cases, the diversity highlighted by RFLP of flagellin genes exceeded the diversity present in H antigens. Our finding about the genetic variation of flagellin genes encoding the same H antigen is consistent with observations of populations of other diarrheagenic E. coli strains reported in the past (2, 5, 9). The H21 ETEC isolates presented three different patterns, two of which, designated P17a and P17, are identical, respectively, to patterns P21a and P21b found by Botelho et al. (2) in enteropathogenic E. coli strains. Fields et al. (5) showed the importance of the genetic differences among alleles that encode the same H antigen. Using RsaI as a restriction enzyme, they divided H7 isolates into four groups that allowed the differentiation of Shiga toxin-producing strains (O157:H7, O157:Hund, O157:H−, and O55:H7) from most of the other H7 group isolates. In our study, H7 ETEC isolates presented only one RsaI RFLP pattern, which is identical to one of the patterns reported by Fields et al. (5) but different from the one in the reference strain. H19 ETEC isolates showed different RsaI RFLP patterns compared to the respective pattern in the H reference strains. Genetic diversity in the allele that encodes the H19 antigen was also observed by Machado et al. (9), using HhaI as a restriction enzyme. The H molecular typing for members of Enterobacteriaceae may become an important epidemiological tool for the characterization of E. coli pathotypes.

As we mentioned above, H serotyping is the gold standard method for the determination of H antigens. However, it is time-consuming and labor-intensive. Because of these limitations, it is performed by only a few reference laboratories. Moreover, there are additional difficulties associated with conventional H typing. For instance, there is a substantial proportion of nonmotile diarrheagenic E. coli strains as well as cross-reactions between particular H antigens that share common epitopes (4). In fact, we have observed that most nonmotile ETEC strains studied here had their H antigen properly identified by RsaI PCR-RFLP.

The high typeability of fliC PCR-RFLP was demonstrated when this method was applied to previously unknown O:H serotype strains of different diarrheagenic E. coli isolates (data not shown). We were able to characterize the fliC gene from most strains studied, showing the efficacy of this technique for the determination of the H types of E. coli strains. Meanwhile, all ETEC strains that showed discrepant results between the H serotype and the fliC RFLP pattern were confirmed by serotyping to express the expected H antigen by PCR-RFLP.

ETEC belongs to specific serotypes, given by the combination of O and H antigen types. In spite of this serotype diversity, some flagellar antigens are serogroup specific and are often associated with the toxigenic phenotypes LT-I (heat labile toxin I)/ST-I (heat stable toxin I) and ST-I, which are highly associated with diarrhea (10, 12, 16). We performed serotyping of ETEC samples with a previously unknown O:H serotype by fliC RFLP and somatic antigen serotyping (data not shown). Determination of the somatic antigen was guided by the identification of the flagellar antigen of ETEC strains by PCR-RFLP, thus reducing the number of anti-O antigen sera used. PCR-RFLP in conjunction with determination of the O serogroup may become useful in identifying ETEC and related strains that do not express immunoreactive H antigens and could be extended to include other clinically important E. coli strains.

Our results showed that fliC-RFLP analysis is a credible and efficient method for the characterization of the fliC gene from ETEC strains and other pathotypes of E. coli strains. We demonstrated for the first time the molecular patterns of the fliC gene from the most common ETEC serotypes, in addition to the fliC RsaI RFLP patterns from H antigen reference strains. Four different research groups were able to characterize the fliC gene using the same fliC PCR-RFLP method described in this work (personal communication). They were thus capable of typing the fliC gene from E. coli samples belonging to different pathotypes. For wide-scale use of the PCR-RFLP, it is necessary that the fliC molecular patterns obtained by different researchers be compared with previously published molecular patterns. Therefore, our work may aid in the typing of fliC from E. coli, serving as a guide for the typing of fliC and the identification of H antigen from different E. coli pathotypes.

PCR-RFLP proved to be faster than traditional serotyping for the identification of the E. coli H antigens, taking 2 days to complete rather than the 7 or more days necessary for classic H serotyping. For each fliC PCR-RFLP reaction, the basic cost is approximately $9, whereas for H antigen serotyping the cost is approximately $35. A number of concerns could be raised about the fliC-RFLP method. For instance, the fliC gene may not amplify by PCR due to inadequate primer homology. However, we observed that amplification could be obtained in most cases, warranting the use of this technique. Another potential limitation is that, since there are unknown fliC alleles, the profiles from these alleles could not be matched with known fliC-RFLP profiles. However, the molecular profiles of alleles from strains obtained in epidemiological studies may soon be determined and new patterns may be described for the diarrheagenic strains of E. coli, thus permitting widespread use of this technique to characterize the fliC gene and determine the H antigen of E. coli strains. As we discussed above, classic serotyping presents stronger limitations than the fliC-RFLP method. Moreover, the potential limitations of classic serotyping can be bypassed by the fliC-RFLP method. The PCR-RFLP technique is capable of guiding the determination of the O antigen and is an efficient molecular tool for the characterization of the fliC gene from ETEC. Thus, in the future it could replace seroagglutination.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kinue Irino from the Adolf Luts Institute for the H antigen reference strains.

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) to Marina B. Martinez and Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos/Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia/Programa de Apoio a Núcleos de Excelência (FINEP/MCT/PRONEX) to Beatriz E. C. Guth. Scholarship grants were from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, CNPq, Brasilia, Brazil, to A. C. R. Moreno.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amhaz, J. M. K., A. Andrade, S. Y. Bando, T. L. Tanaka, C. A. Moreira-Filho, and M. B. Martinez. 2004. Molecular typing and phylogenetic analysis of enteroinvasive Escherichia coli using the fliC gene sequence. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 235:259-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botelho, B. A., S. Y. Bando, L. R. Trabulsi, and C. A. Moreira-Filho. 2003. Identification of EPEC and non-EPEC serotypes in the EPEC O serogroups by PCR-RFLP analysis of the fliC gene. J. Microbiol. Methods 54:87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coimbra, R. S., M. Lefevre, F. Grimont, and P. A. Grimont. 2001. Clonal relationships among Shigella serotypes suggested by cryptic flagellin gene polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:670-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ewing, W. H. 1999. Edwards & Ewing's identification of Enterobacteriaceae, 4th ed. Elsevier Science Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 5.Fields, P. I., K. Blom, H. J. Hughes, L. O. Helsel, P. Feng, and B. Swaminathan. 1997. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding H antigen in Escherichia coli and a development of a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism test for identification of E. coli O157:H7 and O157:NM. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1066-1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iino, T. Genetics of structure and function of bacterial flagella. 1977. Annu. Rev. Genet. 11:161-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joys, T. M. The flagellar filament protein. 1988. Can. J. Microbiol. 34:452-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahali, S., B. Sarkar, S. Chakraborty, R. Macaden, J. S. Deokule, M. Ballal, R. K. Nandy, S. K. Bhattacharya, Y. Takeda, and T. Ramamurthy. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli associated with sporadic cases and outbreaks of diarrhoea between 2000 and 2001 in India. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 19:473-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machado, J., F. Grimont, and P. A. D. Grimont. 2000. Identification of Escherichia coli flagellar types by restriction of the amplified fliC gene. Res. Microbiol. 151:535-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura, L. S., L. C. S. Ferreira, A. B. F. Pacheco, and B. E. C. Guth. 1996. Relationship between outer membrane protein and lipopolysaccharide profiles and serotypes of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated in Brazil. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 143:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid, S. D., R. K. Selander, and T. S. Whittam. 1999. Sequence diversity of flagellin (fliC) alleles in pathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:153-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reis, M. H. L., B. E. C. Guth, T. A. T. Gomes, J. Murahovschi, and L. R. Trabulsi. 1982. Frequency of Escherichia coli strains producing heat-labile toxin or heat-stable toxin or both in children with and without diarrhea in São Paulo. J. Clin. Microbiol. 15:1062-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, L., D. Rothemund, H. Curd, and P. R. Reeves. 2000. Sequence diversity of the Escherichia coli H7 fliC genes: implication for a DNA-based typing scheme for E. coli O157:H7. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1786-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, L., D. Rothemund, H. Curd, and P. R. Reeves. 2003. Species-wide variation in the Escherichia coli flagellin (H-antigen) gene. J. Bacteriol. 185:2936-2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winstanley, C., and J. A. W. Morgan. 1997. The bacterial flagellin gene as a biomarker for detection, population genetics and epidemiological analysis. Microbiology 143:3071-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf, M. K. 1997. Occurrence, distribution, and associations of O and H serogroups, colonization factor antigens, and toxins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:569-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. 2004. State of the art of new vaccines: research and development: initiative for vaccine. 2003 W.H.O. report on initiative for vaccine research (IVR). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 18.Zhang, W. L., M. Bielaszewska, J. Bockemuhl, H. Schmidt, F. Scheutz, and H. Karch. 2000. Molecular analysis of H antigens reveals that human diarrheagenic Escherichia coli O26 strains that carry the eae gene belong to the H11 clonal complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2989-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]