Abstract

Here we provide evidence that the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins of budding yeast act together with Dmc1, a meiosis-specific, RecA-like recombinase. The mei5 and sae3 mutations reduce sporulation, spore viability, and crossing over to the same extent as dmc1. In all three mutants, these defects are largely suppressed by overproduction of Rad51. In addition, mei5 and sae3, like dmc1, suppress the cell-cycle arrest phenotype of the hop2 mutant. The Mei5, Sae3, and Dmc1 proteins colocalize to foci on meiotic chromosomes, and their localization is mutually dependent. The localization of Rad51 to chromosomes is not affected in either mei5 or sae3. Taken together, these observations suggest that the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins are accessory factors specific to Dmc1. We speculate that Mei5 and Sae3 are necessary for efficient formation of Dmc1-containing nucleoprotein filaments in vivo.

MEIOSIS is a special type of cell cycle that produces haploid gametes from diploid parental cells. Unique to meiosis is the reductional division in which homologous chromosomes segregate to opposite poles. During the prophase that precedes this division, homologs pair with each other and undergo high levels of genetic recombination. Recombination plays at least two important roles in segregating chromosomes. First, it ensures that each chromosome finds its homolog. Second, a fraction of meiotic recombination events leads to reciprocal exchange (crossing over), which establishes physical connections between homologs. These connections, called chiasmata, ensure the proper alignment of chromosomes on the spindle apparatus at meiosis I.

The molecular mechanism of meiotic recombination has been well characterized in budding yeast. Meiotic recombination starts with double-strand breaks (DSBs) catalyzed by the Spo11 protein (Keeney 2001). Strands with 5′-termini at DSB ends are selectively degraded to leave single-strands with 3′-ends (Sun et al. 1991; Bishop et al. 1992), which are thought to be used for homology searching by strand-exchange proteins. The single-stranded DNA tails invade homologous sequences in nonsister chromatids to form single-end invasion intermediates, which may then be further processed to form double-Holliday junctions (Schwacha and Kleckner 1994; Hunter and Kleckner 2001).

During vegetative growth in budding yeast, gene products belonging to the RAD52 epistasis group are involved in DSB repair through homologous recombination (Paques and Haber 1999; Symington 2002; Sung et al. 2003). Among them, Rad51, a homolog of the bacterial RecA protein, plays a major role in homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange. Rad51 functions in recombination by assembling as highly ordered oligomers on single-stranded DNA (Ogawa et al. 1993; Symington 2002). Formation of this structure, called a presynaptic filament, requires a group of accessory proteins, including Rad52 and the Rad55/57 heterodimer (Sung 1997a,b; New et al. 1998).

Rad51, Rad52, Rad55, and Rad57 also play essential roles in meiotic recombination (Borts et al. 1986; Shinohara et al. 1992; Schwacha and Kleckner 1997). In the absence of these proteins, DSBs are not efficiently converted to joint molecules. In wild type, formation of Rad51 presynaptic filaments is cytologically detectable at multiple distinct sites on chromatin, in response to DSB formation (Bishop 1994). Consistent with biochemical data, Rad52, Rad55, and Rad57 are necessary for foci formation by Rad51 during meiosis (Gasior et al. 1998).

Dmc1 is a meiosis-specific homolog of bacterial RecA that functions specifically in meiotic recombination (Bishop et al. 1992). In the absence of Dmc1, unrepaired DSBs accumulate with hyperresected ends (Bishop et al. 1992). In vitro, the Dmc1 protein promotes renaturation of complementary single-stranded DNA and assimilation of homologous single-stranded DNA into duplex DNA (Hong et al. 2001). Cytological studies have shown that Dmc1 forms many foci on chromosomes during meiosis, substantially overlapping with Rad51 foci (Bishop 1994).

Although both Rad51 and Dmc1 play important roles in meiotic recombination, a number of observations suggest that Rad51 plays a more critical role than Dmc1. First, localization of Rad51 to chromosomes is not affected in the absence of Dmc1, whereas localization of Dmc1 is severely reduced in the absence of Rad51 (Bishop 1994). Second, in a certain strain background, the dmc1 mutant forms some viable spores (∼20%), but essentially all spores are inviable in the rad51 mutant (Rockmill et al. 1995b). Third, overproduction of Rad51 suppresses the dmc1 defects in crossing over and viable spore production (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003).

A recent study suggests that the early steps in meiotic recombination can proceed through two different pathways. One pathway relies on Rad51, but not Dmc1 (referred to as the Rad51-only pathway); the other utilizes both Dmc1 and Rad51 (referred to as the Dmc1-dependent pathway; Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003). Interestingly, the Dmc1-dependent pathway requires at least two proteins that are not involved in the Rad51-only pathway. These are Hop2 and Mnd1, two meiosis-specific proteins that interact with each other (Leu et al. 1998; Rabitsch et al. 2001; Gerton and DeRisi 2002; Tsubouchi and Roeder 2002). Epistasis analysis indicates that the Hop2/Mnd1 complex functions downstream of Dmc1 and is required for accurate homology searching in the Dmc1-dependent pathway (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003). Previous studies have shown that the dmc1 null mutant defect in meiotic cell-cycle progression varies in different yeast strain backgrounds. In an SK1 strain background, the dmc1 mutant arrests in meiotic prophase (Bishop et al. 1992); however, in a BR2495 strain background, the dmc1 mutant undergoes meiotic nuclear division after a delay (Rockmill et al. 1995b). This difference between strains could be due to different levels of Rad51 protein and/or differences in the relative activity of the Rad51-only pathway of meiotic recombination (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003).

In the same way that Rad51 requires Rad52, Rad55, and Rad57 for efficient strand exchange, Dmc1 might require accessory factors. Since Dmc1 is produced only in meiotic cells, its accessory factors might also be meiosis specific. Two candidate genes that might encode Dmc1 accessory factors are MEI5 and SAE3. In the SK1 strain background, the mei5 mutant fails to undergo efficient nuclear division despite an apparently normal premeiotic S phase (Rabitsch et al. 2001). This phenotype is one of the hallmarks of mutants defective in the Dmc1-dependent recombination pathway (Bishop et al. 1992). The sae3 mutant also arrests at meiotic prophase in SK1 strains. Meiotic DSBs become hyperresected, and the production of mature recombinants is reduced to ∼10% of the wild-type level (McKee and Kleckner 1997). Recently, the SAE3 gene was proposed to have an intron and to encode a protein homologous to the fission yeast Swi5 protein (Akamatsu et al. 2003). Here, we present genetic and cytological evidence indicating that the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins act in the Dmc1-dependent pathway of meiotic recombination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids:

Yeast strains used in this study are summarized in Table 1. Strains are isogenic with the haploid strain BR1919-8B (Rockmill and Roeder 1990), unless otherwise stated. Isogenic derivatives of S3246 were constructed by mating appropriate haploids; isogenic haploids were generated by transformation and/or by genetic crosses. BR1919-8B strains carrying sae3::URA3 were obtained from J. Novak (Yale University, New Haven, CT).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S3246 |

|

||||||

| TBR310 | S3246 but homozygous hop2::ADE2 | ||||||

| TBR737a |

|

||||||

| TBR751 | S3246 but homozygous mei5::KAN | ||||||

| TBR821 | S3246 but homozygous MEI5-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR860 | S3246 but homozygous hop2::ADE2 mei5::KAN | ||||||

| TBR869 | S3246 but homozygous dmc1::KAN | ||||||

| TBR885 | S3246 but homozygous hop2::ADE2 dmc1::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1028a | TBR737 but homozygous dmc1::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1039 | S3246 but homozygous sae3::URA3 | ||||||

| TBR1044 | S3246 but homozygous hop2::ADE2 sae3::URA3 | ||||||

| TBR1053 | S3246 but homozygous dmc1::KAN mei5::KAN sae3::URA3 | ||||||

| TBR1063a | TBR737 but homozygous sae3::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1084 | S3246 but homozygous sae3::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1087 | S3246 but homozygous hop2::ADE2 dmc1::KAN mei5::KAN sae3::URA3 | ||||||

| TBR1089a | TBR737 but homozygous mei5::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1098 | S3246 but homozygous spo11::ADE2 MEI5-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1099 | S3246 but homozygous hop2::ADE2 MEI5-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1136 | S3246 but homozygous dmc1::URA3 MEI5-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1247 | S3246 but homozygous sae3::URA3 MEI5-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1744 | S3246 but homozygous SAE3-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1772 | S3246 but homozygous spo11::ADE2 SAE3-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1773 | S3246 but homozygous hop2::ADE2 SAE3-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1774 | S3246 but homozygous dmc1::URA3 SAE3-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1775 | S3246 but homozygous mei5::KAN SAE3-myc::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1797a | TBR737 but homozygous dmc1::URA3 sae3::KAN | ||||||

| TBR1798a | TBR737 but homozygous dmc1::URA3 mei5::KAN |

These diploid strains consist of a MATa strain isogenic with BR1919-8B and a MATα strain congenic with BR1919-8B. The MATα-bearing chromosomes in these strains are circular.

The following constructs were described previously: YEpFAT4-RAD51 (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003) and plasmids for introducing hop2::ADE2 (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2002) and dmc1::URA3 (Bishop et al. 1992) disruptions. dmc1::KAN, mei5::KAN, and sae3::KAN were engineered by PCR-mediated gene disruption (Longtine et al. 1998). The kanMX cassette was used to replace the entire open reading frame (ORF) of DMC1 and MEI5 and the previously annotated ORF for SAE3 (McKee and Kleckner 1997). Sequences encoding 13 copies of the myc epitope were integrated at the 3′-end of the MEI5 gene and at the 3′-end of the newly annotated SAE3 ORF by the PCR-mediated method of Longtine et al. (1998).

Cytology:

Meiotic chromosomes were surface spread, and immunostaining was carried out as described previously (Sym et al. 1993; Chua and Roeder 1998). Rabbit and mouse anti-Red1 antibodies were used at 1:500 dilution (Smith and Roeder 1997). Rabbit anti-Rad51 and anti-Dmc1 antibodies were used at 1:500 dilution (Shinohara et al. 1992; Bishop 1994). Rabbit anti-Zip1 antibodies were used at 1:100 dilution (Sym et al. 1993). Mouse anti-myc antibody was used at 1:100 dilution (Covance).

RT-PCR:

RT-PCR was done as described previously (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2002). RNA was reverse transcribed using the following primer: TTAGTCCTTCATTGAATAACCGAT. The resulting cDNA was amplified using the above primer and the following primer: ATGAACTATTTGGAAACACAGTTA.

Measuring sporulation:

From single colonies, patches were made on YPD plates (or on selection plates when necessary) and incubated at 30° overnight. The plates were replica plated onto sporulation medium and incubated at 30° for 2 or 3 days. For each strain, spore formation was measured in three independent experiments, with at least 300 cells scored in each experiment.

Statistics:

To compare the colocalization of Mei5 (or Sae3) with Dmc1 vs. Rad51, contingency chi-square tests were performed. For example, for chromosome spreads stained for both Mei5 and Dmc1, Mei5 foci were divided into two groups: those colocalizing with Dmc1 and those not colocalizing; similarly, the numbers of Mei5 foci colocalizing or not colocalizaing with Rad51 were determined. Using these two sets of numbers, a chi-square value was calculated, and the corresponding probability (P-value) was obtained. Using the same method, the fraction of Dmc1 foci containing Mei5 was compared to the fraction of Rad51 foci containing Mei5. The same methods were used to assess overlap between Sae3 and Dmc1/Rad51.

RESULTS

Genetic analysis places MEI5 and SAE3 in the same recombination pathway as DMC1:

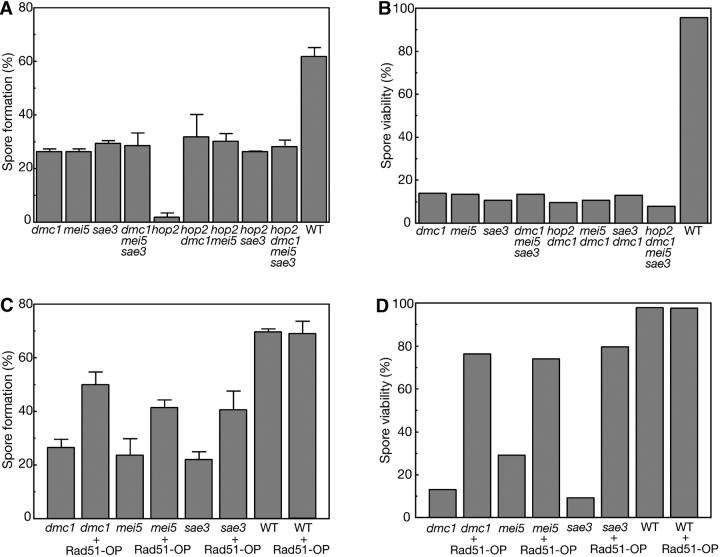

To further characterize the mei5 and sae3 mutants, the MEI5 and SAE3 genes were deleted in the BR1919-8B strain background, in which the dmc1 mutant sporulates with reduced efficiency (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003). Both the mei5 mutant and the sae3 mutant exhibit levels of sporulation and spore viability similar to dmc1 (Figure 1, A and B). The dmc1 mei5 sae3 triple mutant also shows the same levels of sporulation and spore viability as each single mutant (Figure 1, A and B), strongly suggesting that the affected gene products work in the same pathway.

Figure 1.—

Sporulation and spore viability in mei5, sae3, and dmc1 strains carrying a hop2 mutation or overproducing Rad51. (A and C) Cells were sporulated at 30° for 2 (A) or 3 (C) days; spore formation was measured as described in materials and methods. Error bars represent standard deviations. (B and D) To measure spore viability, 44 tetrads were dissected for each strain. Strains analyzed in A and B are wild type (WT, S3246), dmc1 (TBR869), hop2 (TBR310), mei5 (TBR751), sae3 (TBR1039), hop2 dmc1 (TBR885), hop2 mei5 (TBR860), hop2 sae3 (TBR1044), dmc1 mei5 sae3 (TBR1053), and hop2 dmc1 mei5 sae3 (TBR1087). Strains analyzed in C and D carry the multicopy vector YEpFAT4 containing either no insert or RAD51; only those carrying a vector with RAD51 are indicated as + Rad51-OP. OP, overproduction. Plasmid-bearing strains were derived from wild type (WT, S3246), dmc1 (TBR869), mei5 (TBR751), and sae3 (TBR1084).

The hop2 mutant shows complete cell-cycle arrest in the BR1919-8B background (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2002). The dmc1 hop2 double mutant sporulates to the same extent as dmc1, indicating that dmc1 is epistatic to hop2 (Figure 1A; Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003). The mei5 hop2 and sae3 hop2 double mutants show sporulation and spore viability similar to dmc1 hop2 (Figure 1, A and B), indicating that mei5 and sae3 also suppress hop2. Furthermore, the hop2 dmc1 mei5 sae3 quadruple mutant is indistinguishable from the double mutants (Figure 1, A and B). Thus, it is likely that Mei5, Sae3, and Dmc1 act in the same recombination pathway at a step upstream of Hop2/Mnd1.

Another phenotype characteristic of mutants defective in the Dmc1-dependent recombination pathway is that their defects in sporulation and viable spore production can be suppressed by overproduction of Rad51 (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003). Overproduction of Rad51 improves spore formation and viability in the mei5 and sae3 mutants to an extent similar to that seen in the dmc1 mutant (Figure 1, C and D). This observation provides further evidence that Mei5 and Sae3 are involved in the Dmc1-dependent recombination pathway.

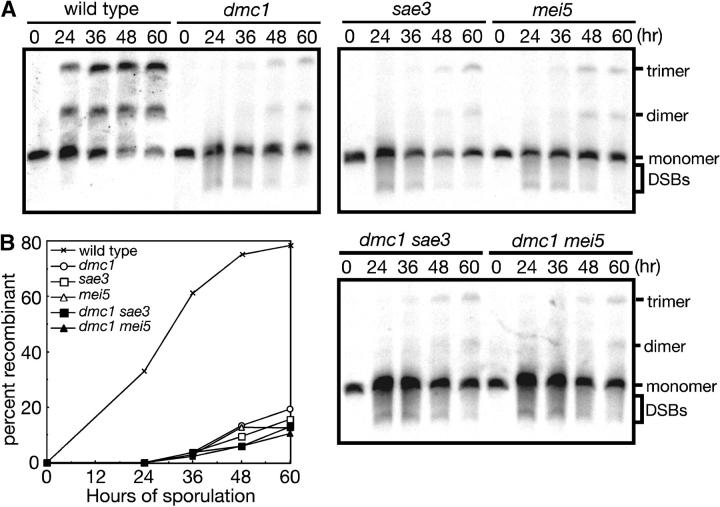

The mei5, sae3, and dmc1 mutations reduce crossing over to the same extent:

To determine the effect of mei5 on the formation of mature recombinants and to compare mei5 with dmc1 and sae3 (Bishop et al. 1992; McKee and Kleckner 1997), crossing over was assayed physically in diploid strains carrying one linear and one circular copy of chromosome III. A single crossover between one linear and one circular chromatid results in production of a linear dimer. A double crossover involving one linear chromatid and both chromatids of the circular chromosome generates a linear trimer. The linear monomers, dimers, and trimers can be separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (circular chromosomes do not enter the gel). In wild type, after 60 hr of sporulation, ∼80% of total DNA entering the gel is recombinant (Figure 2, A and B). In all three mutants, the band representing linear monomers is accompanied by a substantial amount of DNA migrating faster than the intact monomer (Figure 2, A and B). These fragments of lower molecular weight represent molecules resulting from double-strand breakage (Rockmill et al. 1995a), and their persistence indicates that the mutants are defective in DSB repair. Furthermore, the mutants produce a smaller amount of linear dimers and trimers compared to wild type, and these do not appear until much later than their wild-type counterparts (Figure 2, A and B). The timing and extent of crossing over are similar in the mei5, sae3, and dmc1 mutants.

Figure 2.—

Crossing over is reduced in dmc1, mei5, and sae3 mutants. (A) Diploids containing one circular and one linear copy of chromosome III were introduced into sporulation medium and samples were harvested at the time points indicated. Genomic DNA was subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis followed by Southern blot analysis, hybridizing with a probe containing the THR4 gene on chromosome III (Chua and Roeder 1998; Agarwal and Roeder 2000). The positions of linear monomers, dimers, and trimers and of molecules that have sustained one or more DSBs are indicated to the right of the gel. (B) Quantitative analysis of physical recombinants. To calculate the percentage of DNA in crossover products (percentage of recombinants), the sum of signals for dimer and trimer molecules was divided by the sum of signals for monomers, dimers, and trimers (plus DSBs if applicable) for each lane. Strains analyzed are wild type (WT, TBR737), dmc1 (TBR1028), sae3 (TBR1063), mei5 (TBR1089), dmc1 sae3 (TBR1797), and dmc1 mei5 (TBR1798).

Consistent with the spore formation and viability data shown in Figure 1, the dmc1 sae3 and dmc1 mei5 double mutants show essentially the same phenotype as each single mutant with respect to the extent and kinetics of crossover formation (Figure 2, A and B). These data further support the conclusion that Dmc1, Mei5, and Sae3 act in the same pathway.

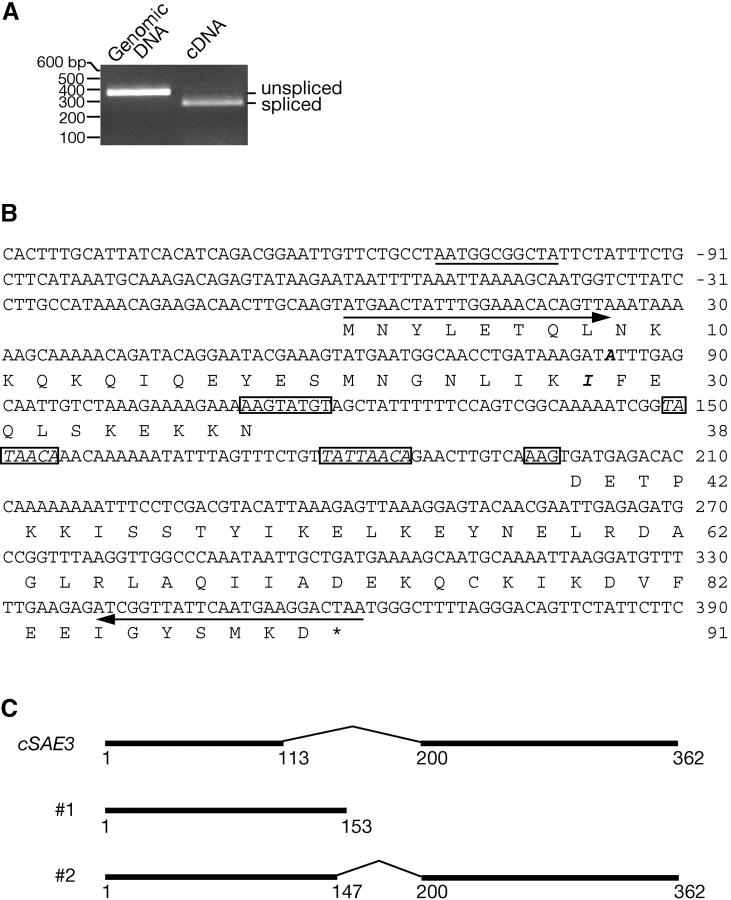

The SAE3 gene contains an intron:

Recently, the SAE3 gene was proposed to have an intron and to encode a member of a family of proteins homologous to the fission yeast Swi5 protein (Akamatsu et al. 2003). To confirm that SAE3 pre-mRNA is spliced, mRNA from meiotic cells was reverse transcribed, and the resultant cDNA was amplified by PCR using primers flanking any potential introns. The DNA amplified from cDNA was found to be smaller than the DNA amplified from genomic DNA, indicating that the mRNA is indeed spliced (Figure 3A). The sequence of the cDNA revealed a new ORF for the SAE3 gene (Figure 3, B and C), with a different 5′ splice junction from the one predicted previously (Akamatsu et al. 2003). The intron contains a well-conserved 5′ splice site and a 3′ splice site that is used relatively infrequently (Figure 3B; Rymond and Rosbash 1992). However, no sequence matching the conserved branchpoint sequence (TACTAACA; Rymond and Rosbash 1992) is present. Instead, two closely related sequences are found (Figure 3B). In the first (TATAACA), the third C in the consensus sequence is missing. In the second (TATTAACA), the third C in the consensus sequence is replaced with T. In summary, the SAE3 gene contains an intron 86 nucleotides in length and encodes a protein of 91 amino acids (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.—

The SAE3 gene has an intron. (A) Genomic and cDNA derived from meiotic mRNA were amplified by PCR with primers and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. (B) DNA sequence and encoded amino acid sequence of SAE3. Consensus splicing signals are boxed. Italicized boxed sequences indicate potential branchpoint sequences (see text). A URS1 consensus sequence is underlined. Primers used for PCR amplification are shown with arrows. Compared to the sequence of strain S288c published in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org), the SK1 strain from which SAE3 cDNA was derived has a polymorphism at the 83rd nucleotide—A (italicized in boldface type) instead of G. The single nucleotide substitution changes the 28th amino acid from M to I (italicized in boldface type). Numbering starts at the first nucleotide of the first codon for the DNA sequence and the first amino acid for the amino acid sequence. (C) Structure of SAE3 ORFs. The structure of the cDNA found in this study is shown on top. Structure 1 was proposed by McKee and Kleckner (1997). Structure 2 was proposed by Akamatsu et al. (2003).

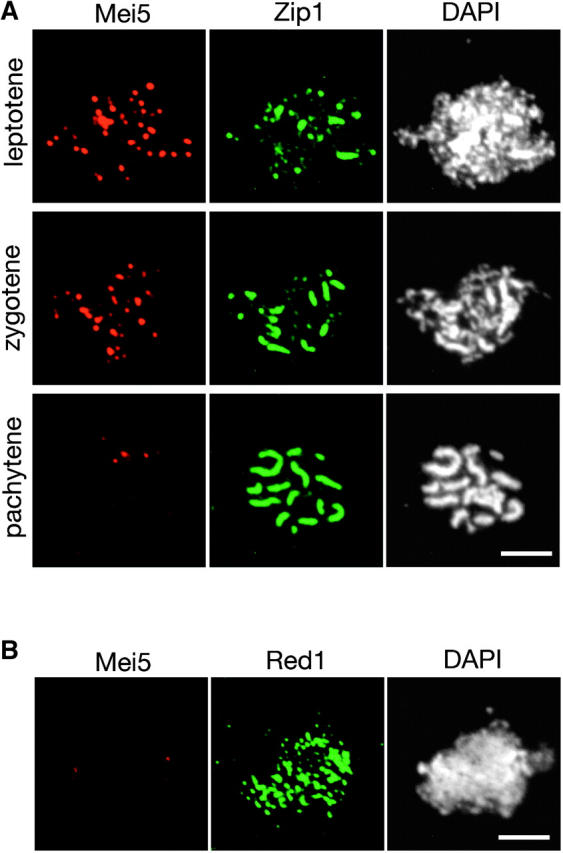

The Mei5 and Sae3 proteins localize to chromosomes as foci in a SPO11-dependent manner:

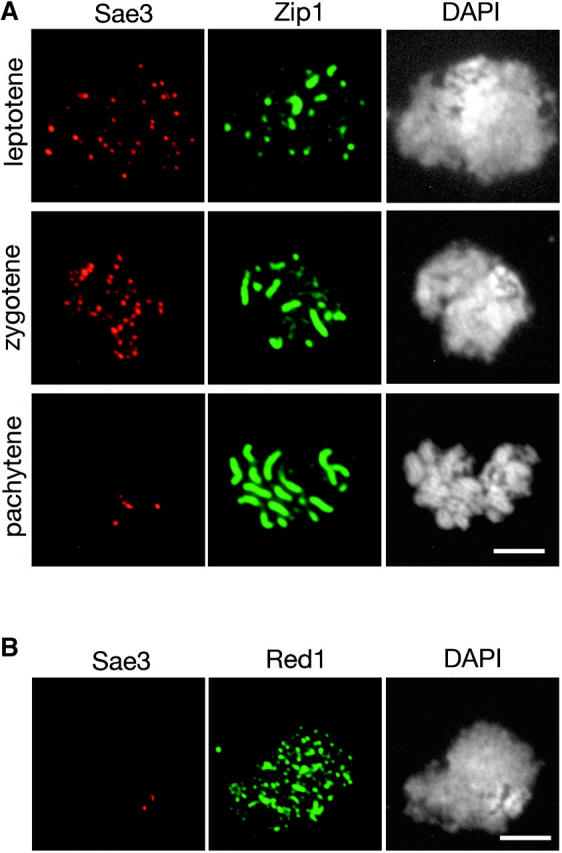

To determine the in vivo localization of Mei5 and Sae3, the proteins were tagged with the myc epitope and immunolocalized in spread meiotic nuclei. Diploid strains in which both copies of the MEI5 (or SAE3) gene have been replaced by MEI5-myc (or SAE3-myc) display wild-type levels of spore viability (data not shown), indicating that the tagged proteins are functional (data not shown). Cells at different stages of meiotic prophase were identified on the basis of the staining pattern of the Zip1 protein, which is a major component of the synaptonemal complex and thus serves as a marker for chromosome synapsis (Sym et al. 1993). The Mei5 and Sae3 proteins are present as numerous foci on chromosomes at leptotene (dotty Zip1 staining) and zygotene (dotty plus linear Zip1 staining), but these foci largely disappear by pachytene (linear Zip1; Figures 4A and 5A). This localization pattern is similar to that seen for Rad51 and Dmc1 (Bishop 1994).

Figure 4.—

Localization of Mei5 to meiotic chromosomes. (A) Meiotic chromosomes from wild-type cells producing myc-tagged Mei5 (TBR821) were stained with anti-myc and anti-Zip1 antibodies and with the DNA-binding dye 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (B) Nuclei from spo11 cells producing myc-tagged Mei5 (TBR1098) were stained with anti-myc and anti-Red1 antibodies and with DAPI. Bars, 4 μm.

Figure 5.—

Localization of Sae3 to meiotic chromosomes. (A) Meiotic chromosomes from wild-type cells producing myc-tagged Sae3 (TBR1744) were stained with anti-myc and anti-Zip1 antibodies and with DAPI. (B) Nuclei from spo11 cells producing myc-tagged Mei5 (TBR1772) were stained with anti-myc and anti-Red1 antibodies and with DAPI. Bars, 4 μm.

To test if Mei5 and Sae3 localization to chromosomes requires the initiation of meiotic recombination, these proteins were immunolocalized in the spo11 mutant. To identify cells at prophase I, chromosomes were simultaneously stained with antibodies to the Red1 protein, which is a component of the cores of meiotic chromosomes. Unlike Zip1, Red1 localizes to chromosomes independently of meiotic recombination (Smith and Roeder 1997). Like Rad51 and Dmc1 (Bishop 1994; Gasior et al. 1998), little or no Mei5 or Sae3 is present on chromosomes in the spo11 mutant (Figures 4B and 5B). The residual Mei5/Sae3 foci observed in spo11 are at least five times less intense than those seen in wild type. These faint foci may reflect nonspecific sticking of the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins to chromosomes. Alternatively, Mei5 and Sae3 might localize weakly to chromosomes even in the absence of DSBs. Taken together, these results are consistent with direct roles for Mei5 and Sae3 in meiotic recombination.

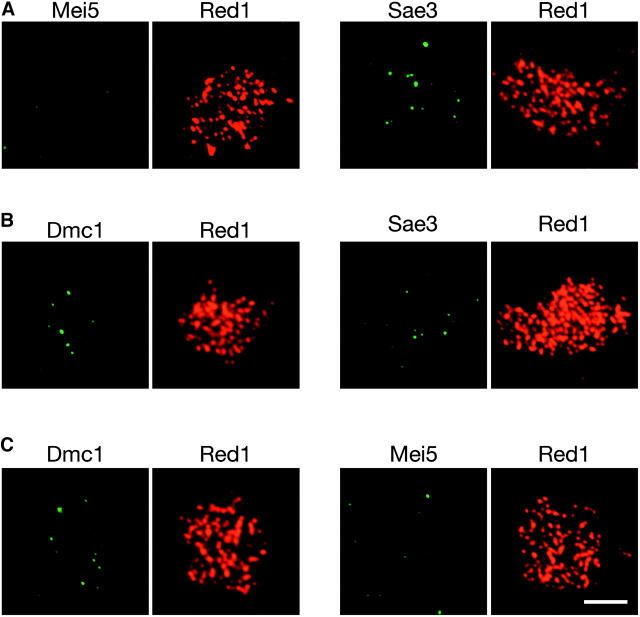

Localization of the Mei5, Sae3, and Dmc1 proteins to chromosomes is mutually dependent:

The kinetics of foci formation by Mei5, Sae3, Rad51, and Dmc1 are similar, raising the possibility that these proteins work together in the meiotic recombination pathway. However, previous studies showed that Rad51 and Dmc1 foci do not completely overlap (Dresser et al. 1997; Shinohara et al. 2000). To examine if Mei5 and Sae3 associate with one or both of these RecA homologs, co-immunostaining of Dmc1 and either Mei5 or Sae3 and of Rad51 and either Mei5 or Sae3 was carried out.

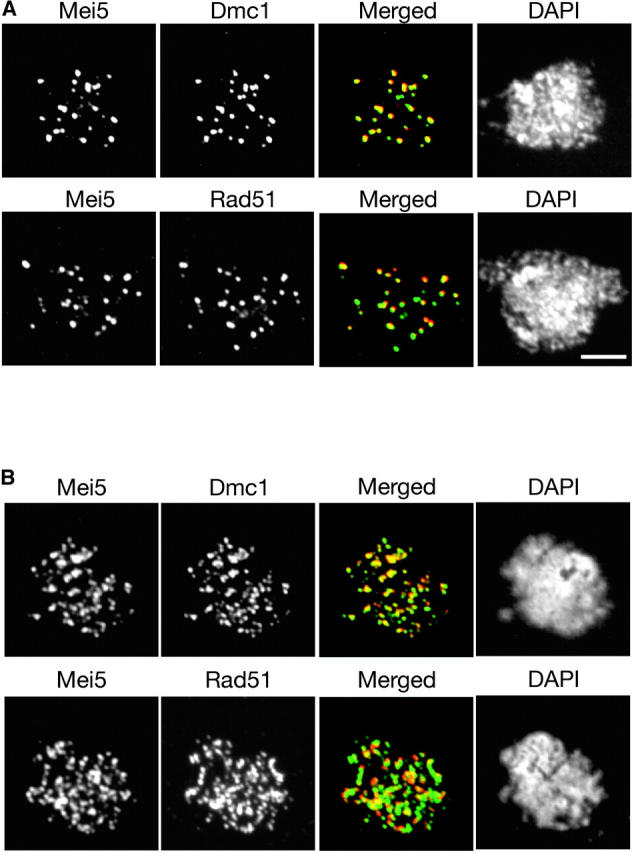

Both Mei5 and Sae3 show extensive colocalization with both Dmc1 and Rad51 (Figures 6A and 7A). However, the extent of overlap is much greater for Dmc1 than for Rad51 (Table 2). This trend is most pronounced in the hop2 mutant background, in which all four proteins accumulate on chromosomes (Figures 6B and 7B; Table 2).

Figure 6.—

Co-immunostaining of Mei5 with Rad51 or Dmc1. Meiotic chromosomes from (A) wild type producing myc-tagged Mei5 (TBR821) or (B) the hop2 mutant producing myc-tagged Mei5 (TBR1099) were stained with anti-myc and either anti-Rad51 or anti-Dmc1 antibodies and with DAPI. Bar, 4 μm.

Figure 7.—

Co-immunostaining of Sae3 with Rad51 or Dmc1. Meiotic chromosomes from (A) wild type producing myc-tagged Sae3 (TBR1744) or (B) the hop2 mutant producing myc-tagged Sae3 (TBR1773) were stained with anti-myc and either anti-Rad51 or anti-Dmc1 antibodies and with DAPI. Bars, 4 μm.

TABLE 2.

Colocalization of foci

| Colocalization frequencies (%)

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type

|

hop2

|

|||||||||

| Dmc1Y | n | Rad51Y | n | P-value | Dmc1Y | n | Rad51Y | n | P-value | |

| Mei5X | 86.8 | 311 | 73.3 | 592 | 4.9 × 10−6 | 97.9 | 1064 | 85.9 | 808 | 6.7 × 10−23 |

| 86.5 | 312 | 78.5 | 553 | 4.6 × 10−3 | 97.3 | 1071 | 79.7 | 1064 | 1.2 × 10−35 | |

| Sae3X | 95.3 | 465 | 85.3 | 517 | 3.4 × 10−7 | 97.8 | 1002 | 93.7 | 1164 | 6.8 × 10−6 |

| 95.1 | 466 | 86.8 | 508 | 1.5 × 10−5 | 97.5 | 1005 | 87.0 | 1257 | 5.8 × 10−19 | |

For each pair of proteins, there are two rows of numbers, with the first row indicating the percentage of foci of protein X (Mei5 or Sae3) that overlaps with foci of protein Y (Dmc1 or Rad51); the second row indicates the percentage of foci of protein Y that overlaps with protein X. n indicates the total number of foci of protein X (first row for each protein) or Y (second row for each protein) that were scored; the number of nuclei examined ranged from 8 to 15. The P-value indicates the probability that the frequency of overlap between Rad51 and Mei5 (or Sae3) is the same as the frequency of overlap between Dmc1 and Mei5 (or Sae3). The method used to calculate P-values is described in materials and methods.

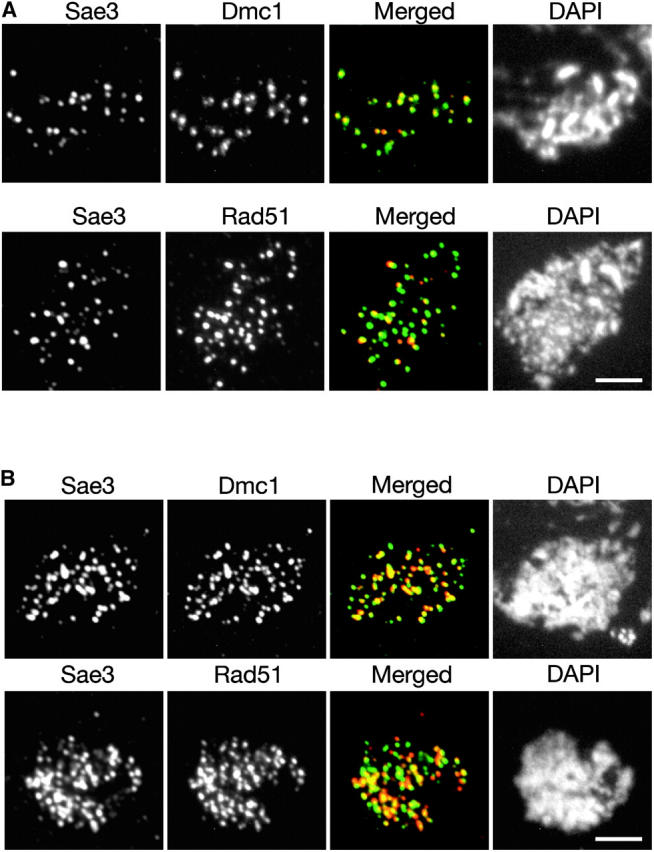

The formation of Mei5 and Sae3 foci is largely abolished in the dmc1 mutant (Figure 8A). Similarly, formation of Dmc1 and Sae3 foci is nearly eliminated in the mei5 mutant (Figure 8B), and formation of Dmc1 and Mei5 foci is abolished in the sae3 mutant (Figure 8C). Thus, localization of Mei5, Sae3, and Dmc1 to chromosomes is mutually dependent. In each case, some residual staining of low signal intensity is observed on chromosome spreads. This staining may reflect nonspecific background staining or a low level of localization for each protein in the absence of its partners.

Figure 8.—

Chromosomal localization of Mei5, Dmc1, and Sae3 is mutually dependent. (A) Nuclei from a dmc1 mutant producing either myc-tagged Mei5 (TBR1136) or myc-tagged Sae3 (TBR1774) were stained with anti-myc and anti-Red1 antibodies. (B) Nuclei from a mei5 mutant (TBR751) and a mei5 mutant producing myc-tagged Sae3 (TBR1775) were stained with anti-Dmc1 or anti-myc and anti-Red1 antibodies. (C) Nuclei from the sae3 mutant producing myc-tagged Mei5 (TBR1247) were stained with anti-Red1 and either anti-Dmc1 or anti-myc antibodies. Bar, 4 μm.

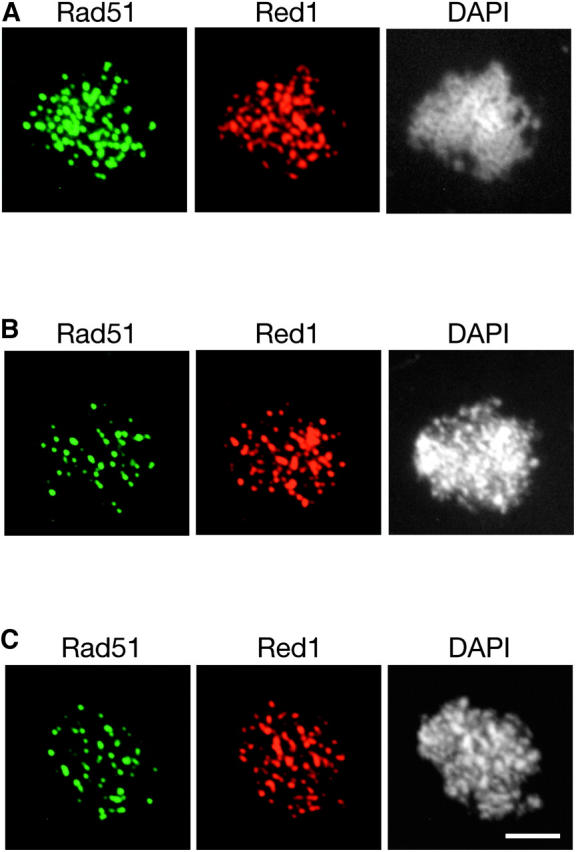

Previous studies showed that the absence of Dmc1 does not affect the localization of Rad51 (Bishop 1994). The localization of Rad51 was tested in the dmc1, mei5, and sae3 mutants. As expected, Rad51 still forms foci in these mutants (Figure 9).

Figure 9.—

Rad51 localizes to chromosomes in the dmc1, mei5, and sae3 mutants. Meiotic chromosomes from (A) dmc1 (TBR869), (B) mei5 (TBR751), and (C) sae3 (TBR1039) mutants were stained with anti-Rad51 and anti-Red1 antibodies and also with DAPI. Bar, 4 μm.

DISCUSSION

The Mei5 and Sae3 proteins work in the Dmc1-dependent recombination pathway:

Here, we provide genetic and cytological evidence that the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins work at the same step as Dmc1 in the Dmc1-dependent meiotic recombination pathway. First, mutations in all three genes reduce sporulation and spore viability to the same extent. Second, like dmc1, mei5 and sae3 mutations suppress cell-cycle arrest in the hop2 mutant. Third, Rad51 overproduction suppresses the mei5 and sae3 defects in sporulation and spore viability, as is the case for dmc1. Fourth, physical analysis of recombination intermediates and products indicates that mei5, sae3, and dmc1 reduce meiotic DSB repair and crossing over to a similar extent, and recombination is reduced to the same degree in the dmc1 mei5 and dmc1 sae3 double mutants. Fifth, the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins are found together with Dmc1 as many foci on chromosomes during prophase I, with the number increasing from leptotene through zytotene and then disappearing through pachytene. Furthermore, the localization of Mei5, Sae3, and Dmc1 to chromosomes is mutually dependent.

The Mei5 and Sae3 proteins may be accessory factors to Dmc1:

It seems likely that Dmc1 is directly involved in homology searching and strand exchange in meiotic recombination for the following reasons. First, Dmc1 is a homolog of the bacterial RecA protein (Bishop et al. 1992). Second, the dmc1 mutant is strongly defective in meiotic recombination. In the SK1 strain background, there is robust accumulation of hyperresected DSBs (Bishop et al. 1992). Furthermore, recombination intermediates such as single-end invasions and double Holliday junctions are completely absent in dmc1 SK1 strains (Schwacha and Kleckner 1995; Hunter and Kleckner 2001).

Early studies of Dmc1 protein purified from yeast and human cells failed to detect the strong strand-exchange activity characteristic of Rad51 (Li et al. 1997; Masson et al. 1999; Hong et al. 2001). Furthermore, the human Dmc1 protein was originally reported to form stacked ring structures on DNA (Masson et al. 1999; Passy et al. 1999) instead of the helical nucleoprotein filaments reported for RecA and Rad51 (Dunn et al. 1982; Flory and Radding 1982; Ogawa et al. 1993). Recently, however, human Dmc1 was found to have strong strand-exchange activity in vitro, although this activity is highly sensitive to salt concentration and pH (Sehorn et al. 2004). Furthermore, under conditions conducive to strand exchange in vitro, human Dmc1 forms helical nucleoprotein filaments similar in appearance to those formed by Rad51 (Sehorn et al. 2004).

Like Rad51, Dmc1 may require special cofactors for maximal filament formation and strand-exchange activity in vivo. The Mei5 and Sae3 proteins are obvious candidates for these cofactors, since Dmc1 cannot localize to chromosomes in their absence. The following observations strongly suggest that Mei5 and Sae3 act in conjunction with Dmc1 as components of the recombination machinery. First, the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins localize to chromosomes as foci, and the timing of appearance and disappearance of these foci is consistent with the appearance and disappearance of DSBs (Cao et al. 1990; Padmore et al. 1991). Second, localization of Mei5 and Sae3 to chromosomes is dependent on the initiation of meiotic recombination. Third, Mei5 and Sae3 foci significantly overlap with Dmc1 foci. Fourth, the localization of Mei5, Sae3, and Dmc1 to chromosomes is mutually dependent. We propose that the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins are necessary for efficient filament formation and/or strand exchange mediated by Dmc1.

Although both Mei5 and Sae3 are necessary for Dmc1 localization on chromosomes, they are not required for Rad51 localization, suggesting that they are factors specific for Dmc1. On the other hand, Rad51 is necessary for wild-type levels of localization of Dmc1, Mei5, and Sae3 to chromosomes (Bishop et al. 1992; our unpublished data). One possibility for this Rad51 dependency is that certain recombination intermediates created by Rad51 are necessary for efficient loading of the Dmc1, Sae3, and Mei5 proteins onto chromosomes. Alternatively, a protein-protein interaction between Rad51 and these proteins might be necessary for their chromosomal localization.

How might Mei5 and Sae3 promote Dmc1-mediated strand exchange?

Rad51-mediated strand exchange occurs in a number of steps (Sung et al. 2003). First, Rad51 assembles on single-stranded DNA to form a helical filament, called the presynaptic filament. Next is the synaptic phase during which duplex DNA is incorporated into the filament and sampled for homology. Once homology is found, alignment between the duplex and the single strand becomes stabilized. The final step is strand exchange during which the complementary strand from the duplex is progressively taken up into the filament.

At what stage might Mei5 and Sae3 act, assuming that strand exchange by Rad51 and Dmc1 are mechanistically related? Our genetic results suggest that the Mei5 and Sae3 proteins, just like Dmc1, act upstream of the step that involves Hop2/Mnd1. The Mei5, Sae3, and Dmc1 proteins accumulate excessively in the hop2 mutant. These phenotypes argue that Mei5 and Sae3 act together with Dmc1 before the strand-exchange step in the recombination reaction. The Hop2/Mnd1 complex is proposed to promote accurate homology searching in the Dmc1-dependent recombination pathway (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2003). In the absence of either Hop2 or Mnd1, interactions between nonhomologous sequences become inappropriately stabilized and nucleate synaptonemal complex formation. Taken together, these results suggest that Mei5 and Sae3 act either in the formation of presynaptic filaments or in the synaptic phase of homology searching.

A number of proteins are known to be involved in the assembly of presynaptic filaments involving Rad51, including RPA, Rad52, Rad54, Rad55, and Rad57 (Paques and Haber 1999; Symington 2002; Sung et al. 2003). RPA is a single-stranded DNA-binding protein complex that plays a role in removing secondary structure from single-stranded DNA. Interestingly, RPA competes with Rad51 for binding DNA; when single-stranded DNA is covered with RPA before Rad51, assembly of the Rad51 presynaptic filament is hindered (Sugiyama et al. 1997; Sung 1997b). Rad52, Rad54, and the Rad55-Rad57 complex promote nucleation of Rad51 by overcoming the inhibitory effect of RPA (Sung et al. 2003; Wolner et al. 2003). Rad54 is a nonessential component of the Rad51 filament; Rad54/Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments are more stable than filaments lacking Rad54. Rad54 may also be active in the synaptic phase where it has been postulated to endow the presynaptic filament with the ability to actively scan duplex DNA for homology (Petukhova et al. 1998, 2000).

It is likely that at least some Rad51 accessory factors are also involved in Dmc1-mediated strand exchange in vivo. Indeed, strand exchange in vitro mediated by the human Dmc1 protein absolutely requires RPA and is enhanced in the presence of Rad54B (Sehorn et al. 2004). Mei5 and/or Sae3 may substitute for certain Rad51 accessory factors, or these meiotic proteins may function in a unique capacity. Perhaps a nucleoprotein complex consisting of Dmc1, Mei5, and Sae3 is particularly well equipped to promote strand exchange in the context of meiosis-specific chromosome structure. Both Rad51 and Dmc1 appear to act at most DSB sites, raising the possibility that Mei5 and Sae3 play a role in coordinating the activities of these two recombinases. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the fission yeast Swi5 protein (a Sae3 homolog) has been shown to interact with Rph51 (fission yeast Rad51; Akamatsu et al. 2003). If budding yeast Sae3 can interact with both Dmc1 and Rad51, then it may serve as a bridge between these proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Douglas Bishop, Janet Novak, and Akira Shinohara for providing yeast strains and antibodies. We are grateful to Neal Mitra and Beth Rockmill for comments on the manuscript. H.T. especially thanks Tomomi Tsubouchi for critical reading of an early version of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Agarwal, S., and G. S. Roeder, 2000. Zip3 provides a link between recombination enzymes and synaptonemal complex proteins. Cell 102: 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akamatsu, Y., D. Dziadkowiec, M. Ikeguchi, H. Shinagawa and H. Iwasaki, 2003. Two different Swi5-containing protein complexes are involved in mating-type switching and recombination repair in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 15770–15775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D. K., 1994. RecA homologs Dmc1 and Rad51 interact to form multiple nuclear complexes prior to meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 79: 1081–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D. K., D. Park, L. Xu and N. Kleckner, 1992. DMC1: a meiosis-specific yeast homolog of E. coli recA required for recombination, synaptonemal complex formation, and cell cycle progression. Cell 69: 439–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borts, R. H., M. Lichten and J. E. Haber, 1986. Analysis of meiosis-defective mutations in yeast by physical monitoring of recombination. Genetics 113: 551–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L., E. Alani and N. Kleckner, 1990. A pathway for generation and processing of double-strand breaks during meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell 61: 1089–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua, P. R., and G. S. Roeder, 1998. Zip2, a meiosis-specific protein required for the initiation of chromosome synapsis. Cell 93: 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser, M., D. Ewing, M. Conrad, A. Dominguez, R. Barstead et al., 1997. DMC1 functions in a meiotic pathway that is largely independent of the RAD51 pathway. Genetics 147: 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, K., S. Chrysogelos and J. Griffith, 1982. Electron microscopic visualization of recA-DNA filaments: evidence for a cyclic extension of duplex DNA. Cell 28: 757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory, J., and C. M. Radding, 1982. Visualization of recA protein and its association with DNA: a priming effect of single-strand-binding protein. Cell 28: 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasior, S. L., A. K. Wong, Y. Kora, A. Shinohara and D. K. Bishop, 1998. Rad52 associates with RPA and functions with Rad55 and Rad57 to assemble meiotic recombination complexes. Genes Dev. 12: 2208–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerton, J. L., and J. L. DeRisi, 2002. Mnd1p: an evolutionarily conserved protein required for meiotic recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 6895–6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, E. L., A. Shinohara and D. K. Bishop, 2001. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dmc1 protein promotes renaturation of single-strand DNA (ssDNA) and assimilation of ssDNA into homologous super-coiled duplex DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 41906–41912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, N., and N. Kleckner, 2001. The single-end invasion: an asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to double-Holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell 106: 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, S., 2001. Mechanism and control of meiotic recombination initiation. Curr. Biol. 52: 1–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu, J.-Y., P. R. Chua and G. S. Roeder, 1998. The meiosis-specific Hop2 protein of S. cerevisiae ensures synapsis between homologous chromosomes. Cell 94: 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., E. I. Golub, R. Gupta and C. M. Radding, 1997. Recombination activities of HsDmc1 protein, the meiotic human homolog of RecA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 11221–11226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach et al., 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson, J.-Y., A. A. Davies, N. Hajibagheri, E. Van Dyke, F. E. Benson et al., 1999. The meiosis-specific recombinase hDmc1 forms ring structures and interacts with hRad51. EMBO J. 18: 6552–6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee, A. H. Z., and N. Kleckner, 1997. Mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that block meiotic prophase chromosome metabolism and confer cell cycle arrest at pachytene identify two new meiosis-specific genes SAE1 and SAE3. Genetics 146: 817–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New, J. H., T. Sugiyama, E. Zaitseva and S. C. Kowalczykowski, 1998. Rad52 protein stimulates DNA strand exchange by Rad51 and replication protein A. Nature 391: 407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, T., X. Yu, A. Shinohara and E. H. Egelman, 1993. Similarity of the yeast Rad51 filament to the bacterial RecA filament. Science 259: 1896–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmore, R., L. Cao and N. Kleckner, 1991. Temporal comparison of recombination and synaptonemal complex formation during meiosis in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66: 1239–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paques, F., and J. E. Haber, 1999. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63: 349–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passy, S. I., X. Yu, Z. Li, C. M. Radding, J.-Y. Masson et al., 1999. Human Dmc1 protein binds DNA as an octameric ring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 10684–10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petukhova, G., S. Stratton and P. Sung, 1998. Catalysis of ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange by yeast Rad51 protein. Nature 393: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petukhova, G., P. Sung and H. Klein, 2000. Promotion of Rad51-dependent D-loop formation by yeast recombination factor Rdh54/Tid1. Genes Dev. 14: 2206–2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabitsch, K. P., A. Toth, M. Galova, A. Schleiffer, G. Schaffner et al., 2001. A screen for genes required for meiosis and spore formation based on whole-genome expression. Curr. Biol. 11: 1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill, B., and G. S. Roeder, 1990. Meiosis in asynaptic yeast. Genetics 126: 563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill, B., J. Engebrecht, H. Scherthan, J. Loidl and G. S. Roeder, 1995. a The yeast MER2 gene is required for meiotic recombination and chromosome synapsis. Genetics 141: 49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill, B., M. Sym, H. Scherthan and G. S. Roeder, 1995. b Roles for two RecA homologs in promoting meiotic chromosome synapsis. Genes Dev. 9: 2684–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rymond, R. C., and M. Rosbash, 1992 Yeast pre-mRNA splicing, pp. 143–192 in The Molecular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Gene Expression, edited by E. W. Jones, J. R. Pringle and J. R. Broach. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Schwacha, A., and N. Kleckner, 1994. Identification of joint molecules that form frequently between homologs but rarely between sister chromatids during yeast meiosis. Cell 76: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha, A., and N. Kleckner, 1995. Identification of double Holliday junctions as intermediates in meiotic recombination. Cell 83: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha, A., and N. Kleckner, 1997. Interhomolog bias during meiotic recombination: meiotic functions promote a highly differentiated interhomolog-only pathway. Cell 90: 1123–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehorn, M. G., S. Sigurdsson, W. Bussen, V. M. Unger and P. Sung, 2004. Human meiotic recombinase Dmc1 promotes ATP-dependent homologous DNA strand exchange. Nature 429: 433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, A., H. Ogawa and T. Ogawa, 1992. Rad51 protein involved in repair and recombination in S. cerevisiae is a RecA-like protein. Cell 69: 457–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, M., S. L. Gasior, D. K. Bishop and A. Shinohara, 2000. Tid1/Rdh54 promotes colocalization of Rad51 and Dmc1 during meiotic recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 10814–10819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. V., and G. S. Roeder, 1997. The yeast Red1 protein localizes to the cores of meiotic chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 136: 957–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, T., E. M. Zaitseva and S. C. Koalczykowski, 1997. A single-stranded DNA-binding protein is needed for efficient presynaptic complex formation by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad51 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 7940–7945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H., D. Treco and J. W. Szostak, 1991. Extensive 3′-overhanging, single-stranded DNA associated with the meiosis-specific double-strand breaks at the ARG4 recombination initiation site. Cell 64: 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, P., 1997. a Function of yeast Rad52 protein as a mediator between replication protein A and the Rad51 recombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 28194–28197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, P., 1997. b Yeast Rad55 and Rad57 proteins form a heterodimer that functions with replication protein A to promote DNA strand exchange by Rad51 recombinase. Genes Dev. 11: 1111–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, P., L. Krejci, S. Van Komen and M. G. Sehorn, 2003. Rad51 recombinase and recombination mediators. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 42729–42732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym, M., J. Engebrecht and G. S. Roeder, 1993. Zip1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 72: 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington, L. S., 2002. Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66: 630–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi, H., and G. S. Roeder, 2002. The Mnd1 protein forms a complex with Hop2 to promote homologous chromosome pairing and meiotic double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 3078–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi, H., and G. S. Roeder, 2003. The importance of genetic recombination for fidelity of chromosome pairing in meiosis. Dev. Cell 5: 915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolner, B., S. van Komen, P. Sung and C. L. Peterson, 2003. Recruitment of the recombinational repair machinery to a DNA double-strand break in yeast. Mol. Cell 12: 221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]