Abstract

Malaria control projects based on the introduction and spread of transgenes into mosquito populations depend on the extent of isolation between those populations. On the basis of the distribution of paracentric inversions, Anopheles gambiae has been subdivided into five subspecific chromosomal forms. Estimating gene flow between and within these forms of An. gambiae presents a number of challenges. We compared patterns of genetic divergence (FST) between sympatric populations of the Bamako and Mopti forms at five sites. We used microsatellite loci within the j inversion on chromosome 2, which is fixed in the Bamako form but absent in the Mopti form, and microsatellites on chromosome 3, a region void of inversions. Estimates of genetic diversity and FST's suggest genetic exchanges between forms for the third chromosome but little for the j inversion. These results suggest a role for the inversion in speciation. Extensive gene flow within forms among sites resulted in populations clustering according to form despite substantial gene flow between forms. These patterns underscore the low levels of current gene flow between chromosomal forms in this area of sympatry. Introducing refractoriness genes in areas of the genome void of inversions may facilitate their spread within forms but their passage between forms may prove more difficult than previously thought.

MALARIA accounts for 300–500 million clinical cases and 1.5–3 million deaths/year, 90% of which occur in Africa (World Health Organization 1993; Marshall 2001). To date, none of the classical approaches to malaria control proved effective in Africa and its incidence is still increasing (Marshall 2001). Among other factors, this is due to the breakdown of mosquito control programs, which in turn is due to a lack of funds, a ban on DDT (Taverne 1999), and the evolution of mosquito resistance to insecticides (Chandre et al. 1999; Coetzee et al. 1999). A number of research groups around the world are now working toward the development of molecular-level techniques for the genetic control of malaria vectors (Rai 1996; Collins et al. 2000). The prime target species are Anopheles gambiae, the main vector of malaria in tropical Africa, as well as An. arabiensis and An. funestus (Cohuet et al. 2004, accompanying article in this issue), two other important vectors. One of the most appealing approaches would be to decrease malaria transmission by spreading genes for refractoriness to Plasmodium into wild vector populations via the release of a genetically modified (GM) strain (Carlson 1996; James et al. 1999). Recent progress includes transforming anopheline germlines (Catteruccia et al. 2000) and mapping refractoriness genes (Vernick et al. 1989; Zheng et al. 1997; Romans et al. 1999). The first strains carrying genes for refractoriness may soon be produced in the laboratory. Parallel efforts are being made to develop drive mechanisms that would ensure that refractory genes were transmitted at higher rates than those expected simply through Mendelien genetics. Transposable elements, viruses, and the intracellular symbiont Wolbachia are receiving increasing attention as potential genetic drive systems (Kidwell and Ribeiro 1992; Ribeiro and Kidwell 1994; Turelli and Hoffmann 1999; Sinkins and O'Neill 2000).

A major concern regarding the introduction and spread of refractoriness genes is the possibility that they cannot be integrated into natural malaria vector populations because of barriers to gene flow (Lanzaro and Tripet 2003). There is ample evidence that the genetic structure of An. gambiae populations, especially in West Africa, is unusually complex (Touré et al. 1998a,b; Powell et al. 1999). Five “chromosomal forms” that may be partially or totally reproductively isolated have been identified on the basis of the distribution of six paracentric inversions, namely the j, b, c, u, and d inversions on the right arm of chromosome 2 and the a inversion on the left arm (Coluzzi and Sabatini 1967; Bryan et al. 1982; Touré et al. 1983; Coluzzi et al. 1985). Similarly, in An. funestus, two chromosomal forms have been described that may be reproductively isolated in some parts of Africa but not in others (Cohuet et al. 2004). Paracentric inversions act as crossover suppression mechanisms and thereby may link and protect coadapted gene complexes (Mayr 1963; Dobzhansky 1970). In An. gambiae they are thought to confer selective advantages under different environmental conditions on their carriers (Coluzzi 1982; Touré et al. 1994). In agreement with that hypothesis, the spatial distribution of inversion karyotypes has been shown to strongly correlate with specific ecological zones (Coluzzi et al. 1985; Touré et al. 1994). In areas where chromosomal forms co-occur, the relative frequencies of inversions also change seasonally, providing further evidence for their adaptive nature (Touré et al. 1994).

No signs of genetic differentiation between chromosomal forms have been found outside inversion areas except in the intergenic spacer (IGS) and transcribed spacer of the ribosomal DNA locus on the X chromosome (della Torre et al. 2001; Gentile et al. 2001; Mukabayire et al. 2001). Microsatellite loci near the ribosomal locus were also found genetically differentiated (Wang et al. 2001). In Mali, the so-called M IGS type was found in near-perfect linkage disequilibrium with the inversion karyotypes characteristic of the Mopti form while the S type is common to the Savanna and Bamako forms. This difference suggests that the Mopti form may be completely reproductively isolated from the other two forms (Favia et al. 1997, 2001). In other parts of West Africa the distribution of M and S molecular types is not linked to chromosomal forms (Gentile et al. 2002) but is still thought to characterize partially or completely isolated populations (della Torre et al. 2002; Wondji et al. 2002). Direct estimates of hybridization rates seem to argue in favor of semipermeable boundaries between the putative M and S taxa (reviewed in Lanzaro and Tripet 2003). In Mali, analyses of the distribution of the M and S types in adult females and the sperm extracted from their spermathecae showed that, despite assortative mating, rare cross-matings do occur between the M and S types (Tripet et al. 2001, 2003). A few larvae and adults exhibiting hybrid-like IGS patterns have also been observed (della Torre et al. 2001; Taylor et al. 2001; Edillo et al. 2002; Diabate et al. 2003). Although strong selection is expected against hybrids, some level of introgression may occur and this could explain the lack of genetic differentiation between forms found in most parts of the genome (Lanzaro et al. 1998; Lanzaro and Tripet 2003).

Complete reproductive isolation between forms of An. gambiae would have important consequences for the GM mosquito project since it would multiply the number of transgenic strains required for transforming malaria vector populations in a given area. However, if residual gene flow between forms occurs, one could hope that introduced refractoriness genes could be spread between forms using areas of sympatry as corridors for gene flow (Lanzaro and Tripet 2003). Estimating gene flow between forms and distinguishing contemporary from historical gene flow or genetic similarity due to common decent is a complex endeavor (Chambers and MacAvoy 2000; Balloux and Lugon-Moulin 2002). A number of studies based on genetic markers have assessed the degree of genetic differentiation between forms (reviewed in Powell et al. 1999; Black and Lanzaro 2001; Lanzaro and Tripet 2003). They usually failed to find significant differentiation between forms outside inversion areas (Cianchi et al. 1983; Lanzaro et al. 1998; Wang et al. 2001) or found significant but low levels of differentiation (Wondji et al. 2002). The question remains, however: How much of that genetic similarity reflects historical vs. contemporary gene flow? In addition, co-ancestry and allele-size homoplasy—i.e., allelic identity by state, but not by descent—may bias gene flow estimates (Estoup and Cornuet 1999; Balloux and Lugon-Moulin 2002).

To assess the relative level of gene flow, we investigated patterns of genetic differentiation among An. gambiae populations in an area of Mali, West Africa, where several forms co-occur. We focused on patterns of genetic divergence (FST) between 10 Bamako and Mopti populations of An. gambiae from five sites as well as one population of An. arabiensis, a sibling species of An. gambiae. Analyses were conducted using allelic frequencies at five microsatellite loci inside the j inversion, which is fixed in the Bamako form but absent from the Mopti form. We assumed no recombination involving Bamako/Mopti genes at loci within the j inversion. This is because heterokaryotypes between the two forms are extremely rare in nature (Touré et al. 1998b) and recombination in heterokaryotypes occurs only through equally rare double crossing over (Krimbas and Powell 1992). A second set of analyses used five microsatellite loci on the third chromosome, which is void of chromosomal inversions and where recombination is expected to occur freely. Rather than conducting isolated pairwise comparisons between forms, we used a hierarchical approach to describe patterns of genetic differentiation between forms as well as within forms and among sites. This approach allowed us to discriminate between (A) a putative genetic structure in which extensive genetic exchange between forms at a single site results in sympatric populations of different forms being more similar than populations of a single form from different locations and (B) a genetic structure in which local gene flow between forms is overridden by gene flow within forms across locations (Figure 1). The potential effects of co-ancestry and homoplasy on estimates of gene flow were evaluated by estimating gene flow in two situations where little is expected: first, between An. gambiae and An. arabiensis, which exhibit premating and postmating reproductive barriers and for which hybridization rates are better known; and second, between the Bamako and Mopti forms of An. gambiae, using the set of loci protected from recombination within the j inversion. This study has important implications for our understanding of patterns of gene flow and speciation in this species complex and, importantly, potential patterns of transgene movement among related taxa.

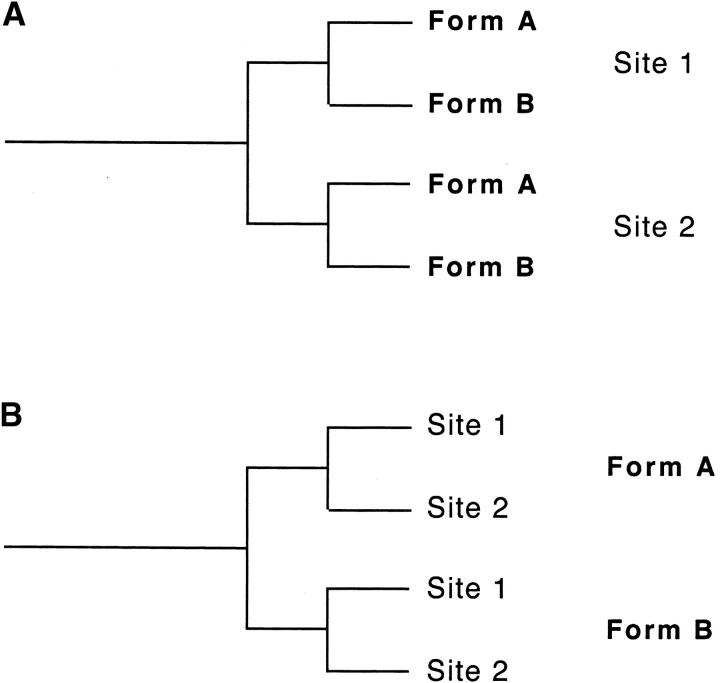

Figure 1.—

Potential genetic structures in complex populations of An. gambiae. In A, local gene exchanges between forms is so high that populations from two forms from site 1 are more similar to each other than are populations of either form from a second site. In B, extensive gene flow between sites within forms overrides local genetic exchanges between forms. The two structures depict two extreme situations, and intermediate patterns (i.e., no clear clustering by site of form) could be expected, depending on the amount of gene flow between forms and within forms and on the geographical distance between the sites under study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites:

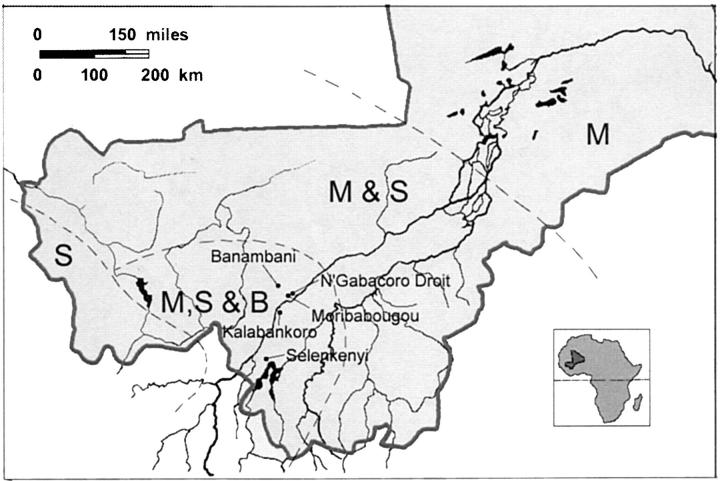

Adult females were collected from huts during the rainy season in July 1993 in Banambani, August 1993 in Selenkenyi, August 1996 in Moribabougou and Kalabankoro, and August 1999 in N'Gabacoro Droit (Figure 2). The villages of Banambani, Kalabankoro, and Selenkenyi are located in the discontinuous habitat characteristic of the upper tributaries of the Niger River, an area that features rocky outcrops and valleys, and enjoy higher rainfalls than the rest of the country. An. gambiae populations in that area are characterized by high proportions of Bamako and Mopti forms while the Savanna form occurs at low frequency in Kalabankoro and Selenkenyi (0–5%) but is common in Banambani (10–40%). Both Moribabougou and N'Gabacoro Droit are located near the Niger River at the start of a vast plateau that extends to the northeast. They exhibit mosquito populations dominated by the Mopti and Bamako forms and a few Savanna individuals (0–5%). An. arabiensis occurs at low frequencies throughout the country (Touré et al. 1998b).

Figure 2.—

Geographical position of Mali (inset) and of the villages of Banambani, Kalabankoro, Moribabougou, N'Gabacoro Droit, and Selenkenyi, where mosquitoes were collected. The dashed lines delimit four zones characterized by the presence of different chromosomal forms of An. gambiae. In zone S and M, the Savanna and Mopti forms are, each time, the only forms to be found. In contrast, in the M and S and in the M, S, and B zones, the Mopti and Savanna or the Mopti, Savanna, and Bamako forms co-occur at various densities; hence these zones could potentially act as corridors for the passage of transgenes between forms.

Identification of karyotypes and molecular forms:

Polytene chromosome preparations were made from the ovaries of semigravid females and DNA was extracted from their head and thorax using established protocols (Coluzzi 1968; Hunt 1973; Post et al. 1993). The chromosomal forms of An. gambiae and An. arabiensis were distinguished by scoring chromosomes by light microscopy. We also determined the IGS rDNA type of all samples using the PCR diagnostic developed by Favia et al. (1997). One individual karyotyped as a Bamako form but exhibiting a Mopti-like M IGS type was excluded from the analyses. The final numbers of karyotyped females used for this study are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Geographical coordinates of the five villages from which sympatric populations ofAn. arabiensisand the Bamako and Mopti forms ofAn. gambiae were analyzed

| Location | Coordinates | Species or form | No. of individuals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Banambani | 12°48′N, 8°3′W | An. arabiensis | 40 |

| Bamako form | 23 | ||

| Mopti form | 40 | ||

| Kalabankoro | 12°28′N, 8°0′W | Bamako form | 11 |

| Mopti form | 19 | ||

| Moribabougou | 12°41′N, 7°57′W | Bamako form | 27 |

| Mopti form | 21 | ||

| N'Gabacoro Droit | 12°41′N, 7°50′W | Bamako form | 21 |

| Mopti form | 23 | ||

| Selenkenyi | 11°42′N, 8°17′W | Bamako form | 39 |

| Mopti form | 40 |

Sample sizes are expressed as number of individuals.

Estimates of genetic diversity and differentiation:

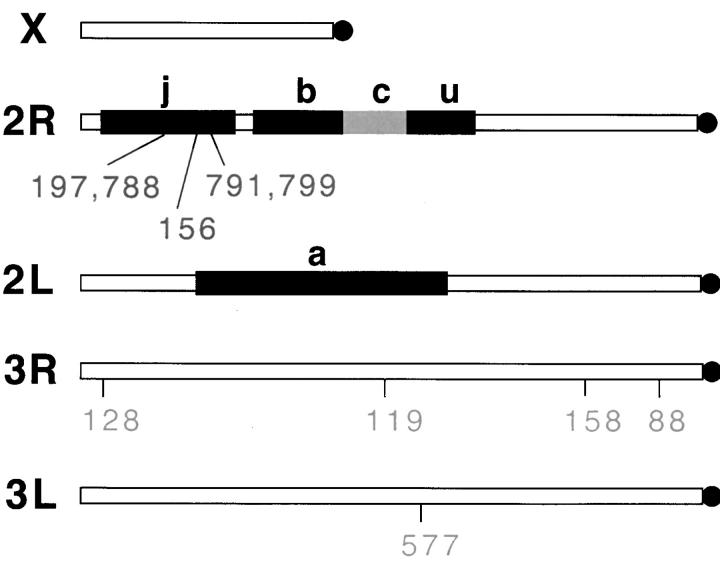

We estimated the amount of genetic differentiation between all populations using 10 microsatellite loci of GT repeats that were isolated and mapped by Zheng et al. (1996) and used in previous studies (Lanzaro et al. 1995, 1998; Tripet et al. 2001). Five loci were on the third chromosome and five were distributed within the j inversion of chromosome 2 (Figure 3). The exact location of the loci was checked by blast searching the An. gambiae genome with the microsatellite-DNA sequence of each locus using the National Center for Biotechnology Information search engine located at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. The loci were PCR amplified using fluorescent primers and a PTC-200 thermal cycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA). PCR products were mixed with a Genescan (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT) size standard and run on an ABI 3100 capillary sequencer (Perkin-Elmer). The gels were analyzed using the ABI PRISM Genescan analysis software and Genotyper DNA fragment analysis software (Perkin-Elmer). Estimates of allelic richness (number of alleles), gene diversity HS, heterozygosity HO, and inbreeding coefficient FIS were calculated using the software package FSTAT (Goudet 2001) available at http://www2.unil.ch/izea/softwares/fstat.html. The same package was used to conduct an exact test of genetic differentiation among all populations (Raymond and Rousset 1995; Goudet et al. 1996). Arlequin version 2.001 (Schneider et al. 2001; available at http://lgb.unige.ch/arlequin/) was used to calculate FST values between all pairs of populations. FST measurements were translated into estimates of the number of migrants per generation (Nm) using the standard formula FST = 1/(4Nm + 1) (Wright 1931).

Figure 3.—

Position of the 10 microsatellite loci used to estimate the amount of genetic differentiation between An. arabiensis and the Bamako and Mopti chromosomal forms of An. gambiae. The loci were located either outside inversion areas on the third chromosome or inside the j inversion that is fixed in the Bamako form and does not occur in the Mopti form. The b inversion is fixed in neither form while the c and u inversions are fixed in the Bamako chromosomal form but are found as floating inversions in the Mopti form.

Cluster analyses and analyses of molecular variance:

We used SYSTAT 5.2 (Wilkinson et al. 1992) to perform neighbor-joining cluster analyses on the matrices of pairwise FST's generated by Arlequin. After the tree was generated, we tested the statistical significance of major branching between two or more members of adjoining taxonomic units by a hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA). We used the AMOVA developed in Arlequin (Excoffier et al. 1992) that is essentially similar to other approaches based on analyses of gene frequencies (Weir and Cockerham 1984; Long 1986). The model of genetic structure tested was used to partition the total variance into covariance components that were then used to compute fixation indices (Wright 1965). The significance level of fixation indices was then tested using a nonparametric permutation approach (see Excoffier et al. 1992 for details). The AMOVA analyses were conducted by locus, an option that allows correcting the degrees of freedom for each locus according to their level of missing data, thus maximizing the power of the analyses (Schneider et al. 2001).

RESULTS

Indices of genetic diversity in relation to forms and locus:

Comparisons of the mean number of alleles, gene diversity HS, and observed heterozygosity HO for loci within the j inversion yielded significant differences between the Bamako and Mopti forms of An. gambiae. In each case, Bamako populations exhibited lower genetic diversity than Mopti (permutation tests: P < 0.05 in all cases). Lower allelic numbers and gene diversities were observed across all five loci. Heterozygosity at locus 197 was the only exception and was slightly higher in the Bamako form (0.800 ± 0.084 as opposed to 0.758 ± 0.086). There was no significant difference between forms in mean inbreeding coefficient FIS. When loci on the third chromosome were considered, no significant differences could be found between Bamako and Mopti forms in terms of mean allelic richness, HS, HO, or FIS (P > 0.05 in all cases).

Genetic differentiation, divergence, and gene flow between species and forms:

The exact test of genetic differentiation (Goudet et al. 1996) yielded significant values between An. arabiensis and An. gambiae populations for loci both inside the j inversion and on the third chromosome (Table 2, underlined data). Genetic differentiation between populations within forms of An. gambiae was mostly nonsignificant for loci both inside and outside the inversion (Table 2, data without underlining or italics). In contrast, genetic differentiation between forms was significant for loci inside the inversion but, for the most part, not significant for loci on the third chromosome (Table 2, italicized data).

TABLE 2.

Matrices of pairwise estimates of genetic divergence (FST) and significance levels of exact tests of genetic differentiation between 10 populations of the Bamako and Mopti forms ofAn. gambiae and a population ofAn. arabiensis from Banambani, Kalabankoro, Moribaboug, N'Gabacoro Droit, and Selenkenyi

| Arab Ban | Bam Ban | Bam Kal | Bam Mori | Bam Ngaba | Bam Sel | Mop Ban | Mop Kal | Mop Mori | Mop Ngaba | Mop Sel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| j inversion | |||||||||||

| Arab Ban | — | ||||||||||

| Bam Ban | 0.111*** | — | |||||||||

| Bam Kal | 0.132*** | 0.047, NS | — | ||||||||

| Bam Mori | 0.089*** | 0.013, NS | 0.031, NS | — | |||||||

| Bam Ngaba | 0.093*** | 0.016, NS | 0.029, NS | 0.014, NS | — | ||||||

| Bam Sel | 0.093*** | 0.001, NS | 0.053, NS | 0.016, NS | 0.029, NS | — | |||||

| Mop Ban | 0.112*** | 0.115*** | 0.081*** | 0.082*** | 0.077*** | 0.114*** | — | ||||

| Mop Kal | 0.110*** | 0.134*** | 0.098*** | 0.082*** | 0.081*** | 0.124*** | 0.033*** | — | |||

| Mop Mori | 0.108*** | 0.092*** | 0.061*** | 0.046*** | 0.053*** | 0.091*** | 0.021** | 0.014, NS | — | ||

| Mop Ngaba | 0.079*** | 0.094*** | 0.066*** | 0.054*** | 0.056*** | 0.083*** | 0.018* | 0.000, NS | 0.000, NS | — | |

| Mop Sel | 0.094*** | 0.089*** | 0.058*** | 0.050*** | 0.059*** | 0.079*** | 0.020, NS | 0.016, NS | 0.004, NS | 0.001, NS | — |

| Third chromosome | |||||||||||

| Arab Ban | — | ||||||||||

| Bam Ban | 0.128*** | — | |||||||||

| Bam Kal | 0.133*** | 0.011, NS | — | ||||||||

| Bam Mori | 0.111*** | −0.004, NS | 0.012, NS | — | |||||||

| Bam Ngaba | 0.119*** | 0.009, NS | 0.015, NS | −0.009, NS | — | ||||||

| Bam Sel | 0.133*** | −0.005, NS | 0.015, NS | 0.008, NS | 0.004, NS | — | |||||

| Mop Ban | 0.135*** | 0.016* | 0.028, NS | 0.017*** | 0.022*** | 0.011* | — | ||||

| Mop Kal | 0.142*** | 0.014, NS | 0.013, NS | 0.027, NS | 0.026* | 0.006, NS | 0.001, NS | — | |||

| Mop Mori | 0.159*** | 0.013, NS | 0.035, NS | 0.027, NS | 0.028* | 0.019, NS | 0.010, NS | 0.025, NS | — | ||

| Mop Ngaba | 0.133*** | 0.027*** | 0.020, NS | 0.011** | 0.014* | 0.014** | 0.011*** | 0.012* | 0.006, NS | — | |

| Mop Sel | 0.13*** | 0.010, NS | 0.023, NS | 0.009** | 0.018, NS | 0.006, NS | 0.002, NS | 0.004, NS | 0.003, NS | 0.006, NS | — |

The top matrix was based on loci inside the j inversion and the bottom one on loci on the third chromosome. Arab, Arabiensis; Bam, Bamako; Mop, Mopti; Ban, Banambani; Kal, Kalabankoro; Mori, Moribabougou; Ngaba, N'Gabacoro Droit; Sel, Selenkenyi. Significant FST's are in boldface type. Between-species comparisons are underlined and between-forms comparisons are in italic type. Significance levels are *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, nonsignificant.

FST estimates between An. arabiensis and An. gambiae were high and significant for loci both inside the j inversion (mean equal to 0.100 ± 0.014 SD) and on the third chromosome (mean equal to 0.132 ± 0.012; Table 2, underlined data). FST's within forms of An. gambiae were generally low for loci both inside (0.019 ± 0.015) and outside the inversion (0.007 ± 0.008) and varied in their levels of significance (Table 2, data with no underlining or italics). In contrast, FST's between forms were high and significant for loci inside the inversion (0.081 ± 0.024; Table 2, italicized data). For loci on the third chromosome, FST's were much lower (0.018 ± 0.008) and many comparisons were not significant (Table 2, italicized data).

We also examined FST estimates between species and forms and within forms, locus by locus, to assess variation among loci. Within-form comparisons were characterized by low FST for all loci (mean 0.016 ± 0.03). The exception was locus 788 in j inversion, which yielded high FST's (0.130 ± 0.105) between Bamako populations but not between Mopti populations (0.003 ± 0.014). Between-form comparisons yielded higher FST values for all loci inside the j inversion (0.084 ± 0.051) compared with those on chromosome 3 (0.022 ± 0.007). The high amounts of genetic divergence observed for locus 788 within the Bamako form generated elevated FST comparisons between forms for this locus (0.168 ± 0.111). Between-species comparisons were characterized by a high amount of variation in FST values with some loci exhibiting very high amounts of divergence and others very little (range 0.035–0.283; mean 0.116 ± 0.030). These patterns were observed for loci both inside the inversion and on the third chromosome.

Cluster analysis and hierarchical analysis of molecular variance:

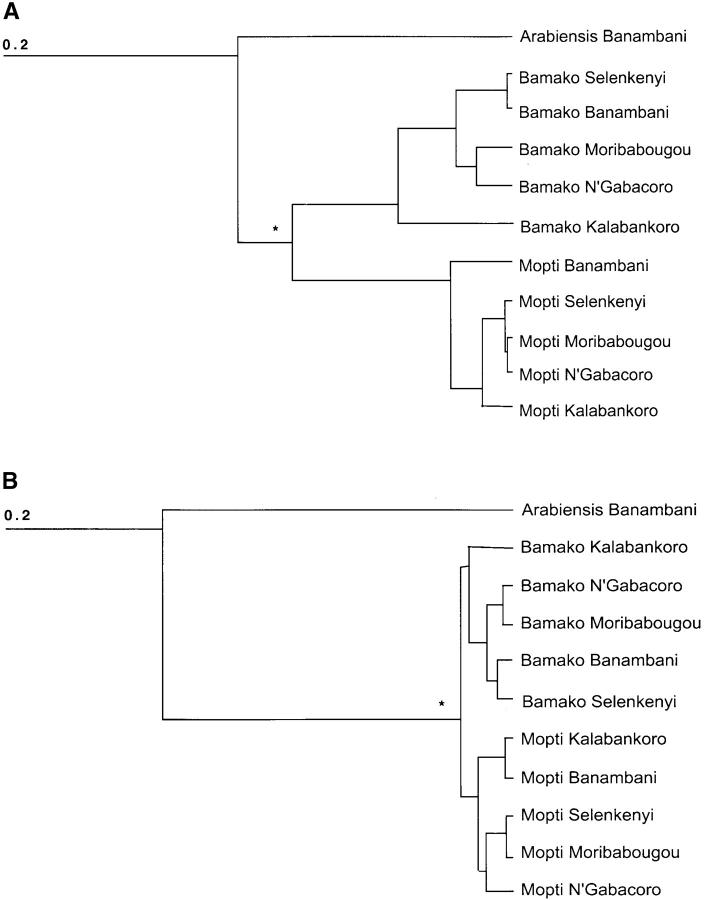

We used the matrices of FST's based on the set of loci inside the j inversion and on chromosome 3 (Table 2) to build neighbor-joining trees of all populations. For loci inside the j inversion the analysis yielded a tree in which forms clustered together, forming two deeply rooted groups (Figure 4A). For loci on chromosome 3, forms were grouped likewise but the branching between forms was a lot shallower (Figure 4B). For both sets of loci, the clusters by form differed significantly as shown by an analysis of molecular variance (see below).

Figure 4.—

Dendrograms performed on the matrix of FST's presented in Table 2, using the neighbor-joining method of cluster analysis. In A, the tree is based on the microsatellite loci inside the j inversion, and in B, the tree is based on microsatellite loci on chromosome 3. Asterisks (*) indicate a significant statistical difference (P < 0.001) between the clusters of Bamako and Mopti populations by an analysis of AMOVA. See text for further details.

Allele frequencies from the 10 sympatric Mopti and Bamako populations from the five villages were fitted to a model of AMOVA partitioning the variance into components of “within site,” “between sites within form,” and “between forms.” For data based on loci inside the j inversion, the between-form component explained nearly 7% of the variance (Table 3). For loci on the third chromosome, this component explained only 1% of the variation (Table 4). The effect of form was highly significant in both models. The within-site and between-site within-form components of the models explained a significant amount of variance for both areas of the genome. Removing locus 788 from the analyses did not change those patterns although it decreased the amount of variance explained by the between-site within-form component of the model presented in Table 3 (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical AMOVA based on microsatellite allele frequencies for loci inside thej inversion inAn. gambiae s.s.

| Source of variation | d.f. | Sum of squares |

Variance components |

Percentage variation |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among forms | 1 | 42.95 | 0.150 | 6.76 | <0.001 |

| Among sites within forms | 8 | 30.98 | 0.037 | 1.66 | <0.001 |

| Within populations | 512 | 1036.80 | 2.026 | 91.58 | <0.001 |

| Total | 521 | 1110.73 | 2.212 |

Analyses were performed using data from the five sites (Banambani, Kalabankoro, Moribabougou, N'Gabacoro Droit, and Selenkenyi) where the Mopti and Bamako chromosomal forms occurred in sympatry. Fixation indices were equal to 0.084 (among forms), 0.018 (among sites within forms), and 0.068 (within populations). An average degree of freedom is presented for simplicity but the AMOVA was conducted by locus with locus-specific degrees of freedom to better account for missing data (see materials and methods for details).

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical AMOVA based on microsatellite allele frequencies for loci on the third chromosome in the Mopti and Bamako chromosomal forms ofAn. gambiae s.s.

| Source of variation | d.f. | Sum of squares |

Variance components |

Percentage variation |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among forms | 1 | 8.70 | 0.022 | 1.06 | <0.001 |

| Among sites within forms | 8 | 23.19 | 0.018 | 0.87 | 0.006 |

| Within populations | 498a | 1006.76 | 2.025 | 98.07 | <0.001 |

| Total | 507 | 1038.65 | 2.065 |

Fixation indices were equal to 0.019 (among forms), 0.009 (among sites within forms), and 0.011 (within populations).

An average degree of freedom is presented for simplicity (see materials and methods for details).

Estimates of gene flow between species and forms:

We translated FST's presented in Table 2 to obtain estimates of the number of migrants per generation Nm between pairs of populations. Concordant with our tests of genetic differentiation and FST estimates, migration between populations within forms was found to be very high for both areas of the genome. Comparisons between the An. arabiensis population and the An. gambiae population yielded Nm's significantly higher than zero for loci inside the j inversion (mean: 2.3 ± 0.4 SD) and on the third chromosome (mean: 1.7 ± 0.2; Table 5). Estimates of migration between forms differed according to the area of the genome considered. For loci in the inversion area, Nm's were low and the variance was low (mean: 3.1 ± 1.0). For loci on chromosome 3, Nm's were considerably higher and more variable (mean: 16.7 ± 9.0). Estimates of migration within forms based on the third chromosome ranged from 9.8 to infinity (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Matrices of gene flow estimates (Nm) between 10 populations of the Bamako and Mopti forms ofAn. gambiae and a population ofAn. arabiensis from the villages of Banambani, Kalabankoro, Moribabougou, N'Gabacoro Droit, and Selenkenyi

| Arab Ban | Bam Ban | Bam Kal | Bam Mori | Bam Ngaba | Bam Sel | Mop Ban | Mop Kal | Mop Mori | Mop Ngaba | Mop Sel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| j inversion | |||||||||||

| Arab Ban | — | ||||||||||

| Bam Ban | 2.0 | — | |||||||||

| Bam Kal | 1.6 | 5.0 | — | ||||||||

| Bam Mori | 2.6 | 19.6 | 7.9 | — | |||||||

| Bam Ngaba | 2.4 | 15.2 | 8.4 | 18.8 | — | ||||||

| Bam Sel | 2.4 | 293.9 | 4.4 | 16.1 | 8.4 | — | |||||

| Mop Ban | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 1.9 | — | ||||

| Mop Kal | 2.0 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 7.4 | — | |||

| Mop Mori | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 11.6 | 17.2 | — | ||

| Mop Ngaba | 2.9 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 13.6 | 640.8 | 1249.8 | — | |

| Mop Sel | 2.4 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 12.3 | 15.3 | 65.5 | 438.3 | — |

| Third chromosome | |||||||||||

| Arab Ban | — | ||||||||||

| Bam Ban | 1.7 | — | |||||||||

| Bam Kal | 1.6 | 23.5 | — | ||||||||

| Bam Mori | 2.0 | Inf | 21.0 | — | |||||||

| Bam Ngaba | 1.9 | 26.7 | 16.5 | Inf | — | ||||||

| Bam Sel | 1.6 | Inf | 16.4 | 31.6 | 62.3 | — | |||||

| Mop Ban | 1.6 | 15.0 | 8.8 | 14.6 | 10.9 | 22.0 | — | ||||

| Mop Kal | 1.5 | 18.0 | 18.8 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 39.5 | 283.8 | — | |||

| Mop Mori | 1.3 | 19.1 | 7.0 | 9.2 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 24.0 | 9.8 | — | ||

| Mop Ngaba | 1.6 | 9.0 | 12.1 | 22.5 | 17.0 | 17.1 | 21.6 | 21.4 | 40.7 | — | |

| Mop Sel | 1.6 | 25.3 | 10.8 | 26.3 | 13.9 | 41.7 | 155.0 | 56.8 | 87.2 | 38.6 | — |

The top matrix was based on loci inside the j inversion and the bottom one on loci on the third chromosome. Arab, Arabiensis; Bam, Bamako; Mop, Mopti; Ban, Banambani; Kal, Kalabankoro; Mori, Moribabougou; Ngaba, N'Gabacoro Droit; Sel, Selenkenyi; Inf, infinity. Between-species comparisons are underlined and between-form comparisons are in italic.

Assuming that Nm's obtained for loci inside the j inversion reflect biases from co-ancestry or allele-size homoplasy (see discussion), we subtracted these from chromosome 3 estimates to obtain conservative estimates of gene flow between forms. The resulting Nm's between populations of the different forms were still considerable (mean: 13.3 ± 9.6). The same analyses were performed without locus 788 with little effect on the outcome (mean: 12.8 ± 9.0).

DISCUSSION

Adaptive inversion and speciation:

The high degree of genetic differentiation and the high FST estimates between forms found for loci inside the j inversion are consistent with the view that this inversion links and protects co-adapted gene complexes from recombination (Dobzhansky and Pavlovsky 1958; Dobzhansky 1970; Coluzzi 1982). The potential role of paracentric inversions for the evolution of species and forms in the An. gambiae complex has been discussed by Coluzzi (1982) and Coluzzi et al. (1985)(2002). Inversions are considered chromosomal mechanisms that preserve gene associations arising in populations that are temporarily isolated in geographically or ecologically marginal habitats (Coluzzi 1982; Coluzzi et al. 1985, 2002). If in such a marginal population an adaptive inversion reaches fixation upon secondary contact with another population, selection against “hybrids” between the two populations may occur. The genetic content of the inversion itself remains largely protected because of the rarity of crossing over in that area of the genome (Krimbas and Powell 1992). These two effects combined may promote the rapid evolution of premating barriers to hybridization and thus may have a fundamental role in speciation processes within the species complex. Rieseberg (2001) and Hey (2003) recently discussed the potential role of inversions in suppressing recombination and providing linkage between genes causing assortative mating and those under disruptive selection in diverging species. In An. gambiae, heterokaryotypes between the Bamako and Mopti forms produce reproductively normal progeny of both sexes (Persiani et al. 1986). Without a direct involvement of the paracentric j inversion in the speciation process through a decrease in fertility of inversion heterozygotes, it seems more plausible that the inversion facilitated speciation through its role as recombination suppressor. If, as suggested here, the Bamako form of An. gambiae is undergoing or has undergone speciation through such a process, it probably did so from a Savanna-like ancestor with whom it shares the S rDNA type. The significantly lower genetic diversity found in the j inversion of the Bamako form as compared to the same area in the Mopti form suggests that indeed the Bamako form may have evolved following the fixation of the j inversion in a small marginal founding population. Whether the j inversion reached fixation under such a process of speciation or another, its content underwent a strong genetic sweep and this is likely to be the main cause of decreased genetic diversity in that area of the genome. This initial loss of diversity has apparently not yet been regenerated by mutation nor has it been recovered by genetic exchange between forms. In contrast, we observed comparable estimates of genetic diversities between the two forms on the third chromosome. In this area of the genome, recombination can occur freely and selection against recombinants may be less intense. The lack of significant genetic differentiation and values of FST's for that area of the genome strongly support the idea that introgression between forms is responsible for those patterns. Recent studies of D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis have reported comparable patterns of genetic differentiation within and outside fixed inversions (Wang et al. 1997; Rieseberg et al. 1999; Machado et al. 2002). Noor et al. (2001) also found genes contributing to hybrid male sterility and female mate preference in D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis that were associated with fixed inversions differing between the two species. Taken together, these results support the view that chromosomal inversions may promote speciation through their role in recombination and patterns of gene flow (Rieseberg 2001; Hey 2003).

Contrary to the Bamako form, the Mopti form could not have diverged from the Savanna-Bamako group under a simple scenario of speciation because it does not feature any characteristic fixed inversion (Touré et al. 1983; Coluzzi et al. 1985). As is the case among members of Drosophila species groups, models of speciation involving inversion fixation can reasonably be assumed in certain cases—e.g., D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis (King 1993; Noor et al. 2001)—but in pairs that do not feature fixed characteristic inversions—e.g., D. pseudoobscura and D. pseudoobscura bogotana—other processes of speciation must be involved (Powell 1997; Wang et al. 1997). At present it is unknown how much gene flow occurs through direct hybridization between the Bamako and Mopti forms or if introgression between the two occurs through the Savanna form. Cytogenetic studies seemed to support the latter by showing frequent hybrid-like heterokaryotypes between the Savanna and Bamako forms and the Savanna and Mopti forms but not between the Bamako and Mopti forms (Touré et al. 1994, 1998b). However, the rDNA diagnostic applied to these heterokaryotypes did not yield hybrid patterns, thereby suggesting that these heterokaryotypes may be the result of floating inversions atypical of each form occurring at low frequencies rather than the result of hybrids (Favia et al. 1997). Whether these atypical inversions are traces of rare introgression events or independent events of chromosomal rearrangements remains to be investigated (Lanzaro and Tripet 2003).

Disentangling past and current gene flow:

Estimating current gene flow within and among forms of An. gambiae is of critical importance in the context of the GM mosquito project. Population genetic studies are required for identifying discrete population groups across Africa, for determining their geographical distribution, and for evaluating the degree to which they are reproductively isolated (Lanzaro and Tripet 2003). They are also necessary to estimate the rate at which genes may spread within and between populations at various spatial scales and to identify biological and physical features of the environment that may interfere with their movements (Lanzaro and Tripet 2003). FST estimates can potentially be biased by allelic identity by descent (co-ancestry) and allelic identity by state (homoplasy; Estoup and Cornuet 1999; Chambers and MacAvoy 2000; Balloux and Lugon-Moulin 2002). Consequently, assessing potential biases can facilitate our interpretations of FST estimates and improve our understanding of An. gambiae's population structure. Taylor et al. (2001), for example, compared estimates of gene flow within the Mopti, Bamako, and Savanna forms derived from FST's with those measured by mark-release-recapture experiments (MRR) between two villages. FST's yielded an estimated Nm = 55.3 ± 54.9 SD and were markedly consistent with the Nm = 56.8 ± 19.7 obtained by MRR (Taylor et al. 2001). In this study we conducted two types of comparisons based on microsatellite loci that could give us a better idea of the effects of co-ancestry and homoplasy on indirect estimates of gene flow. FST's between An. gambiae and its sister species, An. arabiensis, were used to estimate a migration rate, Nm, of ∼2 migrants per generation. This estimate can be compared to direct measures of hybridization rate made by extensive cytogenetic studies, which have shown the frequency of hybridization between the two sister species to be close to 0.05% (White 1970; Petrarca et al. 1991; Touré et al. 1998b). Effective population sizes in a village such as Banambani ranged from 2000 to 6000 (Taylor et al. 1993; Touré et al. 1998a). The product of the hybridization rate and effective population size gives an estimate of one to three hybrids, equivalent to 0.5–1.5 migrants produced per generation. These rough estimations suggest that neither co-ancestry nor homoplasy substantially biased Nm's between the two species. It should be noted, however, that the high variance in FST's observed between loci tends to indicate that some loci may indeed be prone to homoplasy and that overall this may contribute to a slight underestimation of FST's and an overestimation of Nm's. The second type of comparisons we used to assess potential biases were between-form FST's based on loci inside the j inversion. These yielded an average migration rate of three individuals per generation. Assuming, conservatively, that these three migrants solely reflect biases due to co-ancestry and/or homoplasy, we can conclude that these confounding factors do not seriously bias gene flow estimates between the forms of An. gambiae based on microsatellites.

Differentiating ongoing gene flow from gene flow that occurred in the recent past has been and remains the main problem associated with the use of microsatellite markers in the An. gambiae complex. Recent methods based on coalescence theory and maximum likelihoods, such as those implemented in Migrate 1.5 (Beerli 2002) and the combined haplotypes/short-tandem-repeat analyses recently proposed by Hey et al. (2004), offer the possibility of estimating population sizes at divergence as well as gene flow since divergence. These methods can be useful for detecting dispersal between distant populations but their assumptions of constant population sizes and divergence followed by constant gene flow (Beerli and Felsenstein 1999; Hey et al. 2004) limit their use for estimating and interpreting gene flow between forms of An. gambiae. Thus F-statistics currently remain the best tool for studying population structure in An. gambiae despite the difficulties in interpreting pairwise FST's between populations of different forms (Lanzaro and Tripet 2003). Typically, the low levels of genetic divergence between forms characterizing areas of the genome away from inversions have been interpreted as evidence either for incomplete reproductive isolation or for complete reproductive isolation, depending on the authors (e.g., Lanzaro et al. 1998; Wondji et al. 2002; Lanzaro and Tripet 2003). Here, we attempted to compensate for the low interpretative power of isolated between-form comparisons by examining a large number of populations at a wider spatial scale (125 km). If current gene flow is important, one could expect that two sympatric populations of the Bamako and Mopti forms could locally be more similar than two distant populations of the same form. Thus one could expect a genetic structure intermediate between the structures A and B presented in Figure 1. In their early study based on 21 microsatellite loci spanning the entire genome and Bamako and Mopti populations from the villages of Banambani and Selenkenyi, Lanzaro et al. (1998) presented data for the third and the X chromosome suggesting that this might be the case. If current gene flow is low or absent, one can expect within-form gene flow to quickly override these patterns and populations to cluster according to their forms (structure B in Figure 1). Our results show that current gene flow between forms is not high enough to counteract the homogenizing effects of migration between populations within forms. This is true despite significant genetic differentiation between some populations within forms. Thus the question remains as to how much of the theoretical 13 migrants per generation estimated here is due to the few hybrids reported between the M and S forms of An. gambiae and how much is accounted for by past gene flow. Lehmann et al. (2003) recently presented data showing that four distant M-form populations from Senegal, Ghana, Cameroon, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in West and Central Africa were more similar to each other than to any S-form populations. Although the study included only one sympatric S-form population matching the M populations from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, these two populations did not cluster together. These results are consistent with our interpretation of low residual gene flow between forms and suggest that the patterns we found in the area of M/S sympatry in Mali could extend to larger spatial scales.

Consequences for malaria control programs:

The patterns of gene flow reported here have important implications for the mosquito genetic control project. They stress the fact that gene inserts should be targeted to areas of the genome located outside inversions if they are to be spread efficiently. Although we focused on the extreme case of one form possessing a fixed inversion and another not, inversions, fixed or floating, will interfere with the spread of transgenes between populations both within and between forms. This is because recombination rates can be expected to be just as rare in within-forms as in between-form heterokaryotypes. Chromosome 3, which enjoys a higher recombination rate than the X chromosome and the inversion-rich chromosome 2, would be the logical location for gene inserts.

Our results also suggest that multiple transgenic strains will be needed for effective manipulation of malaria vector populations. Our study clearly shows that local residual gene flow between forms is almost negligible compared to the extensive gene flow within forms. Hence, if refractory mosquitoes of one form are released in a given location, the genetic construct will spread over a considerable geographical range before potentially passing to another form. As a result, malaria incidence is not likely to decrease significantly in the area of the release unless all species and forms of vectorial importance are targeted simultaneously. Furthermore, because mosquitoes expressing refractory genes and carrying the genetic-drive system are likely to exhibit some fitness costs (Yan et al. 1997; Catteruccia et al. 2003), simply transforming the most abundant form would leave the opportunity for other mosquito vectors of malaria to expand their ecological niche and out-compete the refractory population (Curtis et al. 1999).

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Caccone, J. Powell, C. Taylor, W. J. Black, D. El Naiem, and M. Slotman for their comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. This work was supported by fellowship no. 823A-061233 from the Swiss National Science Foundation to F.T. and grant no. AI40306 from the National Institutes of Health to G.C.L.

References

- Balloux, F. and N. Lugon-Moulin, 2002. The estimation of population differentiation with microsatellite markers. Mol. Ecol. 11: 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli, P., 2002 MIGRATE: documentation and program, part of LAMARC, Version 1.5. Distributed over the Internet (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/lamarc.html).

- Beerli, P., and J. Felsenstein, 1999. Maximum-likelihood estimation of migration rates and effective populations using a coalescent approach. Genetics 152: 763–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, W. C., and G. C. Lanzaro, 2001. Distribution of genetic variation among chromosomal forms of Anophele gambiae s.s.: Introgressive hybridization, adaptive inversions, or recent reproductive isolation? Insect Mol. Biol. 10: 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, J. H., M. A. Di Deco, V. Petrarca and M. Coluzzi, 1982. Inversion polymorphism and incipient speciation in Anopheles gambiae s. str. in the Gambiae, West Africa. Genetica 59: 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J. O., 1996. Genetic manipulation of mosquitoes: an approach to controlling disease. Trends Biotechnol. 14: 447–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catteruccia, F., T. Nolan, T. G. Loukeris, C. Blass, C. Savakis et al., 2000. Stable germline transformation of the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Nature 405: 959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catteruccia, F., H. C. Godfray and A. Crisanti, 2003. Impact of genetic manipulation on the fitness of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. Science 299: 1225–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, G. K., and E. S. MacAvoy, 2000. Microsatellites: consensus and controversy. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 126: 455–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandre, F., S. Manguin, C. Brengues, J. D. Yovo, F. Darriet et al., 1999. Current distribution of a pyrethroid resistance gene (kdr) in Anopheles gambiae complex from West Africa and further evidence for reproductive isolation of the Mopti form. Parassitologia 41: 319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianchi, R., F. Villani, Y. T. Touré, V. Petrarca and L. Bullini, 1983. Electrophoretic study of different chromosomal forms of Anopheles gambiae s.s. Parassitologia 25: 239–241. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee, M., D. W. K. Horne, B. D. Brooke and R. H. Hunt, 1999. DDT, dieldrin and pyrethroid insecticide resistance in African malaria vector mosquitoes: an historical review and implications for future malaria control in southern Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 95: 215–218. [Google Scholar]

- Cohuet, A., I. Dia, F. Simard, M. Raymond, F. Rousset et al., 2004. Gene flow between chromosomal forms of the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Cameroon, Central Africa, and its relevance in malaria fighting. Genetics 168: 301–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, F. H., L. Kamau, H. A. Ranson and J. M. Vulule, 2000. Molecular entomology and prospects for malaria control. Bull. World Health Organ. 78: 1412–1423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluzzi, M., 1968. Cromosomi politenici delle cellule nutrici ovariche nel complesso gambiae del genere Anopheles. Parassitologia 10: 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Coluzzi, M., 1982 Spatial distribution of chromosomal inversions and speciation in Anopheline mosquitoes, pp. 143–153 in Mechanisms of Speciation: Proceedings From the International Meeting on Mechanisms of Speciation, edited by C. Barigozzi. A. R. Liss, New York. [PubMed]

- Coluzzi, M., and A. Sabatini, 1967. Cytogenetic observations on species A and B of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Parassitologia 9: 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Coluzzi, M., V. Petrarca and M. A. Di Deco, 1985. Chromosomal inversion intergradation and incipient speciation in Anopheles gambiae. Boll. Zool. 52: 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Coluzzi, M., A. Sabatini, A. della Torre, M.A. Di Deco and V. Petrarca, 2002. A polytene chromosome analysis of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Science 298: 1415–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, C. F., H. V. Pates, W. Takken, C. A. Maxwell, J. Myamba et al., 1999. Biological problems with the replacement of a vector population by Plasmodium-refractory mosquitoes. Parassitologia 41: 479–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- della Torre, A., C. Fanello, M. Akogbeto, J. Dossou-yovo, G. Favo et al., 2001. Molecular evidence of incipient speciation within Anopheles gambiae s.s. in West Africa. Insect Mol. Biol. 10: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- della Torre, A., C. Costantini, N. J. Besansky, A. Caccone, V. Petrarca et al., 2002. Speciation within Anopheles gambiae—the glass is half full. Science 298: 115–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabate, A., T. Baldet, C. Chandre, K. R. Dabire, P. Kengne et al., 2003. Kdr mutation, a genetic marker to assess events of introgression between the molecular M and S forms of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) in the tropical savannah area of West Africa. J. Med. Entomol. 40: 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky, T., 1970 Genetics of the Evolutionary Process. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Dobzhansky, T., and O. Pavlovsky, 1958. Interracial hybridization and breakdown of co-adapted gene complexes in Drosophila paulistorum and Drosophila willistoni. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 44: 622–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edillo, F. E., Y. T. Touré, G. C. Lanzaro, G. Dolo and C. E. Taylor, 2002. Spatial and habitat distribution of Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae) in Banambani Village, Mali. J. Med. Entomol. 39: 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estoup, A., and J.-M. Cornuet, 1999 Microsatellite evolution: inferences from population data, pp. 49–65 in Microsatellites: Evolution and Applications, edited by D. B. Goldstein and C. Schlötterer. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Excoffier, L., P. Smouse and J. Quatro, 1992. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: applications to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 131: 479–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favia, G., A. della Torre, M. Bagayoko, A. Lanfrancotti, N. Sagnon et al., 1997. Molecular identifications of sympatric chromosomal forms of Anopheles gambiae and further evidence of their reproductive isolation. Insect Mol. Biol. 6: 377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favia, G., A. Lanfrancotti, L. Spanos, I. Sidén-Kiamos and C. Louis, 2001. Molecular characterization of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) polymorphisms discriminating among chromosomal forms of Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol. Biol. 10: 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, G., M. Slotman, V. Ketmaier, J. R. Powell and A. Caccone, 2001. Attempts to molecularly distinguish cryptic taxa in Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol. Biol. 10: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, G., A. della Torre, B. Maegga, J. R. Powell and A. Caccone, 2002. Genetic differentiation in the African malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae s.s., and the problem of taxonomic status. Genetics 161: 1561–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet, J., 2001 FSTAT: a program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices, Version 2.9.3 (http://www2.unil.ch/izea/softwares/fstat.html).

- Goudet, J., M. Raymond, T. de Meeüs and F. Rousset, 1996. Testing differentiation in diploid populations. Genetics 144: 1933–1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey, J., 2003. Speciation and inversions: chimps and humans. BioEssays 25: 825–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey, J., Y. J. Won, A. Sivasundar, R. Nielsen and J. Markert, 2004. Using nuclear haplotypes with microsatellites to study gene flow between recently separated Cichlid species. Mol. Ecol. 13: 909–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, R. H., 1973. A cytological technique for the study of Anopheles gambiae complex. Parassitologia 15: 137–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, A. A., B. T. Beerntsen, Mde. L. Capurro, C. J. Coates, N. J. Coleman et al., 1999. Controlling malaria transmission with genetically-engineered, Plasmodium-resistant mosquitoes: milestones in a model system. Parassitologia 41: 461–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell, M. G., and J. M. Ribeiro, 1992. Can transposable elements be used to drive disease refractoriness genes into vector populations? Parasitology Today 8: 325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, M., 1993 Species Evolution: The Role of Chromosomal Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Krimbas, C. B., and J. R. Powell, 1992 Drosophila Inversion Polymorphism. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Lanzaro, G. C., and F. Tripet, 2003 Gene flow among populations of Anopheles gambiae: a critical review, pp. 109–132 in Ecological Aspects for Application of Genetically Modified Mosquitoes (Wageningen Frontis Series, Vol. 2), edited by W. Takken and T. W. Scott. Kluwer Academic Press, Dordrecht, The Netherlands (http://library.wur.nl/frontis/malaria/toc.html).

- Lanzaro, G. C., L. Zheng, Y. T. Touré, S. F. Traoré, F. C. Kafatos et al., 1995. Microsatellite DNA and isozyme variability in a West African population of Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol. Biol. 4: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzaro, G. C., Y. T. Touré, J. Carnahan, L. Zheng, G. T. Dolo et al., 1998. Complexities in the genetic structure of Anopheles gambiae populations in west Africa as revealed by microsatellite DNA analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 14260–14265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, T., M. Licht, N. Elissa, B. T. A Maega, J. M. Chimumbwa et al., 2003. Population structure of Anopheles gambiae in Africa. J. Hered. 94: 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, J. C., 1986. The allelic correlation structure of Gainj and Kalam speaking people. I. The estimation of Wright's F-statistics. Genetics 112: 629–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado, C., R. M. Kliman, J. M. Markert and J. Hey, 2002. Inferring the history of speciation from multilocus DNA sequence data: the case of Drosophila pseudoobscura and its close relatives. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 472–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, E., 2001. A renewed assault on an old and deadly foe. Science 290: 428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, E., 1963 Animal Species and Evolution. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Mukabayire, O., J. Caridi, X. Wang, Y. T. Touré, M. Coluzzi et al., 2001. Patterns of DNA sequence variation in chromosomally recognized taxa of Anopheles gambiae: evidence from rDNA and single copy loci. Insect Mol. Biol. 10: 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noor, A. F., K. L. Grams, L. A. Bertucci and J. Reiland, 2001. Chromosomal inversions and the reproductive isolation of species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 12084–12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persiani, A., M. A. Dideco and G. Petrangeli, 1986. Osservzioni di laboratorio su polimorfismi da inversione originati da incroci tra popolazioni diverse di Anopheles gambiae s.s. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 22: 221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrarca, V., J. C. Beier, F. Onyango, J. Koros, C. Asiago et al., 1991. Species composition of the Anopheles gambiae complex (diptera: Culicidae) at two sites in western Kenya. J. Med. Entomol. 28: 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post, R. J., P. K. Flook and A. L. Millest, 1993. Methods for the preservation of insects for DNA studies. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 21: 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, J. R., 1997 Progress and Prospects in Evolutionary Biology: The Drosophila Model. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Powell, J. R., V. Petrarca, A. della Torre, A. Caccone and M. Coluzzi, 1999. Population structure, speciation, and introgression in the Anopheles gambiae complex. Parassitologia 41: 101–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai, K. S., 1996 Genetic control of vectors, pp. 564–574 in The Biology of Disease Vectors, edited by B. J. Beaty and W. C. Marquardt, University Press of Colorado, Niwot, CO.

- Raymond, M., and F. Rousset, 1995. An exact test of population differentiation. Evolution 49: 1280–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, J. M., and M. G. Kidwell, 1994. Transposable elements as population drive mechanisms: specification of critical parameters values. J. Med. Entomol. 31: 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg, L. H., 2001. Chromosomal rearrangements and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15: 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg, L. H., J. Whitton and K. Gardner, 1999. Hybrid zones and the genetic architecture of a barrier to gene flow between two sunflower species. Genetics 152: 713–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romans, P., W. C. Black, R. K. Sakai and R. W. Gwadz, 1999. Linkage of a gene causing malaria refractoriness to Diphenol oxidase-A2 on chromosome 3 of Anopheles gambiae. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 60: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S., D. Roessli and L. Excoffier, 2001 Arlequin: A Software for Population Genetic Data Analysis, Version 2.001. Genetics and Biometry Laboratory, University of Geneva, Geneva.

- Sinkins, S. P., and S. L. O'Neill, 2000 Wolbachia as a vehicle to modify insect populations, pp. 271–287 in Insect Transgenesis: Methods and Applications, edited by A. M. Handler and A. A. James. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Taverne, J., 1999. DDT—To ban or not to ban? Parasitology Today 15: 180–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. E, Y. T. Touré, M. Coluzzi and V. Petrarca, 1993. Effective population size and persistence of Anopheles arabiensis during the dry season of West Africa. Med. Vet. Entomol. 7: 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C., Y. T. Touré, J. Carnahan, D. E. Norris, G. Dolo et al., 2001. Gene flow among populations of the malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae, in Mali, West Africa. Genetics 157: 743–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touré, Y. T., V. Petrarca and M. Coluzzi, 1983. Nueva entita del complesso Anopheles gambiae in Mali. Parrasitologia 25: 367–370. [Google Scholar]

- Touré, Y. T., V. Petrarca, S. F. Traoré, A. Coulibaly, H. M. Maiga et al., 1994. Ecological genetic studies in the chromosomal form Mopti of Anopheles gambiae s. str. in Mali, West Africa. Genetica 94: 213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touré, Y. T., G. Dolo, V. Petrarca, S. F. Traoré, M. Bouaré et al., 1998. a Mark-release-recapture experiments with Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Babambani Village, Mali, to determine population size and structure. Med. Vet. Entomol. 12: 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touré, Y. T., V. Petrarca, S. F. Traoré, A. Coulibaly, H. M. Maiga et al., 1998. b The distribution and inversion polymorphism of chromosomally recognized taxa of the Anopheles gambiae complex in Mali, West Africa. Parassitologia 40: 477–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripet, F., Y. T. Touré, C. E. Taylor, D. E. Norris, G. Dolo et al., 2001. DNA analysis of transferred sperm reveals significant levels of gene flow between molecular forms of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Mol. Ecol. 10: 1725–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripet, F., Y. Touré, G. Dolo and G. C. Lanzaro, 2003. Frequency of multiple inseminations in field-collected Anopheles gambiae females revealed by DNA analysis of transferred sperm. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 68: 1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turelli, M., and A. A. Hoffmann, 1999. Microbe-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a mechanism for introducing transgenes in arthropod populations. Insect Mol. Biol. 8: 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernick, K. D., F. H. Collins and R. W. Gwadz, 1989. A general system of resistance to malaria in Anopheles gambiae controlled by two main genetic loci. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 40: 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. L., J. Wakeley and J. Hey, 1997. Gene flow and natural selection in the origin of Drosophila pseudoobscura and close relatives. Genetics 147: 1091–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R., L. Zheng, Y. Touré, T. Dandekar and F. Kafatos, 2001. When genetic distance matters: measuring genetic differentiation at microsatellite loci in whole-genome scans of recent and incipient species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 10769–10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir, B. S., and C. C. Cockerham, 1984. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38: 1358–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, M. J. D., 1970 Animal Cytology and Evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Wilkinson, L., M. A. Hill and E. Vang, 1992 SYSTAT: Statistics, Version 5.2. SYSTAT, Evanston, IL.

- Wondji, C., F. Simard and D. Fontenille, 2002. Evidence for genetic differentiation between the molecular forms M and S within the forest chromosomal form of Anopheles gambiae in an area of sympatry. Insect Mol. Biol. 11: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 1993 A Global Strategy for Malaria Control. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Wright, S., 1931. Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics 16: 97–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S., 1965. The interpretation of population structure by F-statistics with regard to systems of mating. Evolution 19: 395–420. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G., D. W. Severson and B. M. Christensen, 1997. Costs and benefits of mosquito refractoriness to malaria parasites: implications for genetic variability of mosquitoes and genetic control of malaria. Evolution 51: 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L., M. Q. Benedict, A. J. Cornel, F. H. Collins and F. C. Kafatos, 1996. An integrated genetic map of the African human malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Genetics 143: 941–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L., A. J. Cornel, R. Wang, H. Erfle, H. Voss et al., 1997. Quantitative trait for refractoriness of Anopheles gambiae to Plasmodium cynomolgi B. Science 276: 425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]