Abstract

DNA damage checkpoints regulate gene expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. Some components of the yeast Ccr4-Not complex, which regulates transcription as well as transcript turnover, have previously been linked to DNA damage responses, but it is unclear if this involves transcriptional or post-transcriptional functions. Here we show that CCR4 and CAF1, which together encode the major cytoplasmic mRNA deadenylase complex, have complex genetic interactions with the checkpoint genes DUN1, MRC1, RAD9, and RAD17 in response to DNA-damaging agents hydroxyurea (HU) and methylmethane sulfonate (MMS). The exonuclease-inactivating ccr4-1 point mutation mimics ccr4Δ phenotypes, including synthetic HU hypersensitivity with dun1Δ, demonstrating that Ccr4-Not mRNA deadenylase activity is required for DNA damage responses. However, ccr4Δ and caf1Δ DNA damage phenotypes and genetic interactions with checkpoint genes are not identical, and deletions of some Not components that are believed to predominantly function at the transcriptional level rather than mRNA turnover, e.g., not5Δ, also lead to increased DNA damage sensitivity and synthetic HU hypersensitivity with dun1Δ. Taken together, our data thus suggest that both transcriptional and post-transcriptional functions of the Ccr4-Not complex contribute to the DNA damage response affecting gene expression in a complex manner.

DNA damage checkpoints are signal transduction cascades activated by damage to the genome or replication stalling (reviewed in Nyberg et al. 2002; Longhese et al. 2003). After the initial recognition of damage to DNA or replication blocks, a series of phosphorylation events by checkpoint kinases enables the cell to mount an efficient response that includes a number of effects: arrest of the cell cycle until damage is repaired, regulation of the repair process, transcriptional activation of DNA damage-inducible genes, and in higher organisms, induction of apoptosis. The cell cycle resumes by a regulated process known as recovery when the damage is repaired (Vaze et al. 2002; Leroy et al. 2003).

In budding yeast, Mec1 and its subunit Ddc2 are the most upstream checkpoint kinases and may be able to sense some damage directly (Kondo et al. 2001; Melo et al. 2001; Rouse and Jackson 2002; Zou and Elledge 2003). Mec1 is required for three alternate DNA damage-signaling pathways that are characterized by the mediator proteins Mrc1, Rad9, and Rad17. While the Mrc1 pathway is believed to be specific for damage associated with DNA replication, the other two pathways are activated in response to a variety of lesions throughout the cell cycle (reviewed in Nyberg et al. 2002; Longhese et al. 2003). The mediators link Mec1 to the downstream effector kinases Rad53 and Chk1, thus enabling their activation (Sanchez et al. 1999; Alcasabas et al. 2001; Schwartz et al. 2002; Osborn and Elledge 2003). Together with Mec1, these kinases phosphorylate the checkpoint targets that execute the DNA damage response.

In addition to Rad53 and Chk1, Saccharomyces cerevisiae has a third effector kinase, Dun1, that acts mostly downstream of Rad53 in the checkpoint cascade. Dun1 has important roles in cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase (Gardner et al. 1999), transcriptional induction of damage-inducible genes [such as those coding for ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) subunits; Zhou and Elledge 1993; Gasch et al. 2001], phosphorylation and inhibition of the RNR inhibitor Sml1 (Zhao and Rothstein 2002), and regulation of repair pathways (Bashkirov et al. 2000). However, dun1Δ cells have higher genome instability rates than rad53 mutants (Myung et al. 2001), indicating Rad53-independent functions of Dun1. Similar to Rad53 and its mammalian homolog CHK2, Dun1 contains an N-terminal forkhead-associated (FHA) domain, a phosphothreonine-binding module present in a large number of proteins (reviewed in Durocher and Jackson 2002; Hammet et al. 2003). We recently reported that the FHA domain of Dun1 interacts with the Pan2-Pan3 poly(A) nuclease (Hammet et al. 2002), a complex required for mRNA poly(A) tail length control (Brown and Sachs 1998). Dun1 and Pan2-Pan3 act together in regulating mRNA levels of the DNA repair gene RAD5, and dun1Δ pan2Δ and dun1Δ pan3Δ mutants are synthetically lethal in the presence of replication blocks (Hammet et al. 2002).

Shortening of the poly(A) tail by 3′→5′ exonucleases is the first step in mRNA turnover (reviewed in Parker and Song 2004). In addition to Pan2-Pan3, yeast contains another mRNA deadenylase, the Ccr4-Not complex, which is the major deadenylase responsible for initiating mRNA degradation (Daugeron et al. 2001; Tucker et al. 2001). The Ccr4-Not complex is conserved throughout evolution and in yeast consists of nine defined subunits: Ccr4, Caf1, Not1–Not5, Caf40, and Caf130 (reviewed in Collart 2003; Denis and Chen 2003). Ccr4 is the deadenylase catalytic subunit and contains a 3′→5′ exonuclease domain at its C terminus (Chen et al. 2002; Tucker et al. 2002). Single amino acid substitutions of catalytic residues in the Ccr4 exonuclease domain abolish its mRNA deadenylase activity in vivo and mimic most ccr4Δ phenotypes, indicating that its major cellular function is in mRNA degradation (Chen et al. 2002; Tucker et al. 2002). Although Caf1 also contains a nuclease domain and shows nuclease activity in vitro (Daugeron et al. 2001; Thore et al. 2003), in vivo studies do not support the notion that it is the active nuclease within the Ccr4-Not complex (Viswanathan et al. 2004). Nevertheless, Caf1 is absolutely required for exonuclease activity of Ccr4 in vivo, as caf1Δ mutants show the same deadenylation defects as ccr4Δ (Tucker et al. 2001).

Besides its role in regulating mRNA stability, Ccr4-Not also functions in the initiation and elongation phases of RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription (reviewed in Collart 2003; Denis and Chen 2003). Binding and phenotypic analyses indicate that the complex can be physically and functionally divided into two parts, Ccr4-Caf1 and the Not proteins (Bai et al. 1999; Maillet et al. 2000). Not1 is the core component of the complex and binds Ccr4 and Caf1 via its N terminus, while the other Not subunits are bound via the Not1 C terminus (Bai et al. 1999; Maillet et al. 2000). Although both functional parts of the Ccr4-Not complex contribute to transcriptional as well as post-transcriptional functions, Ccr4-Caf1 seems to be predominantly involved in mRNA deadenylation, whereas the Not proteins are believed to be primarily involved in transcription (Badarinarayana et al. 2000; Denis et al. 2001; Tucker et al. 2002; reviewed in Collart 2003).

Our finding that the poly(A) nuclease Pan2-Pan3 interacts with the checkpoint kinase Dun1 and has a critical role in survival of replication blocks indicated that post-transcriptional mechanisms of regulation of gene expression could be targeted by the DNA damage response pathway in yeast, and we have speculated that this could also involve the Ccr4-Not complex (Hammet et al. 2002). An involvement of the Ccr4-Not in responding to DNA damage is supported by the fact that mutants in several of its subunits, including the mRNA deadenylase catalytic subunit Ccr4, have been found to be sensitive to DNA-damaging agents in a number of whole-genome screens (Bennett et al. 2001; Hanway et al. 2002; Parsons et al. 2004; Westmoreland et al. 2004). To extend these analyses, here we have further investigated the role of the Ccr4-Not complex and its mRNA deadenylase activity in cellular DNA damage responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains:

All strains are isogenic to Y136 (KY803) and are listed in Table 1. The deletion mutants were constructed using standard gene replacement methods. The E556A mutation was introduced in the genomic CCR4 locus by PCR-based allele replacement (Erdeniz et al. 1997) to give the ccr4-1 mutant.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Y136 (KY803) | MATa trp1Δ1 ura3-52 gcn4 leu2::PET56 | Denis et al. (2001) |

| Y210 | As Y136 but not1-2 | Denis et al. (2001) |

| Y214 | As Y136 but not4::URA3 | Denis et al. (2001) |

| Y242 | As Y136 but dun1::LEU2 | This study |

| Y246 | As Y136 but dun1::LEU2 sml1::TRP1 | This study |

| Y294 | As Y136 but ccr4::klURA | This study |

| Y297 | As Y136 but caf1::klURA | This study |

| Y298 | As Y136 but not2::klURA | This study |

| Y299 | As Y136 but not5::klURA | This study |

| Y302 | As Y136 but not5::klURA dun1::LEU2 | This study |

| Y304 | As Y136 but ccr4::klURA dun1::LEU2 sml1::KAN | This study |

| Y305 | As Y136 but caf1::klURA dun1::LEU2 sml1::KAN | This study |

| Y310 | As Y136 but not3::klURA | This study |

| Y317 | As Y136 but ccr4::klURA his3::TRP1 | This study |

| Y319 | As Y136 but caf1::klURA dun1::LEU2 | This study |

| Y332 | As Y136 but ccr4::klURA dun1::LEU2 | This study |

| Y333 | As Y136 but ccr4::klURA rad9::KAN | This study |

| Y334 | As Y136 but ccr4::klURA rad17::KAN | This study |

| Y335 | As Y136 but ccr4::klURA mrc1::KAN | This study |

| Y336 | As Y136 but ccr4::klURA sml1::KAN | This study |

| Y337 | As Y136 but caf1::klURA rad9::KAN | This study |

| Y338 | As Y136 but caf1::klURA rad17::KAN | This study |

| Y339 | As Y136 but caf1::klURA mrc1::KAN | This study |

| Y340 | As Y136 but caf1::klURA sml1::KAN | This study |

| Y345 | As Y136 but sml1::KAN | This study |

| Y346 | As Y136 but rad9::KAN | This study |

| Y347 | As Y136 but rad17::KAN | This study |

| Y348 | As Y136 but mrc1::KAN | This study |

| Y369 (ccr4-1) | As Y136 but ccr4-E556A | This study |

| Y370 | As Y136 but ccr4-E556A dun1::LEU2 | This study |

| Y379 | As Y136 but rpb9::KAN | This study |

| Y380 | As Y136 but rpb9::KAN dun1::LEU2 | This study |

kl, Kluyveromyces lactis.

DNA damage assays:

To test the sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, yeast strains were grown in YPD (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose) to logarithmic phase. Two microliters of 10-fold serial dilutions starting from A600 = 0.5 were spotted onto YPD plates or plates that contained HU or MMS at the doses indicated in the figures. The plates were photographed after 3–5 days.

For survival experiments over a 24-hr time course, overnight cultures were diluted to A600 = 0.2–0.3 and grown for 3 hr before HU was added to 0.1 m. Control samples were taken immediately before HU addition. Survival was followed over a period of 24 hr after addition of HU. Dilutions were plated on YPD plates and viable colonies were counted after 3–5 days depending on the growth rate of the strain. Survival was determined as a percentage of viable colonies relative to the control plate before HU addition. All incubations were done at 30°. For every strain, survival experiments were performed with at least two independent colonies.

Rad53 Western blots:

To analyze Rad53 phosphorylation, cells were HU treated as above, washed three times in YPD, and released into YPD for up to 3 hr as indicated in the figure legend. Protein extracts were prepared using 8 m urea cracking buffer and processed for Rad53 Western blotting as described by Pike et al. (2001)(2003).

Northern blot analysis:

For analysis of gene expression, cells were grown in YPD overnight and diluted to A600 = 0.2–0.3. After 3 hr of growth, cells were treated with 0.1 m HU for another 3 hr. RNA isolation and Northern analysis were performed as described (Hammet et al. 2000). Blots were probed with 32P-labeled RNR3 or ACT1 probes (Pike et al. 2003). After exposure on PhosphorImager screens, the signals were quantified using Molecular Dynamics software. RNR3 levels were normalized to levels of ACT1, and levels of RNR3 message in HU-treated and untreated cells were calculated by comparing expression levels to basal levels of RNR3 expression in the wild type.

RESULTS

CCR4 and CAF1 are required for DNA damage tolerance and show genetic interactions with DUN1:

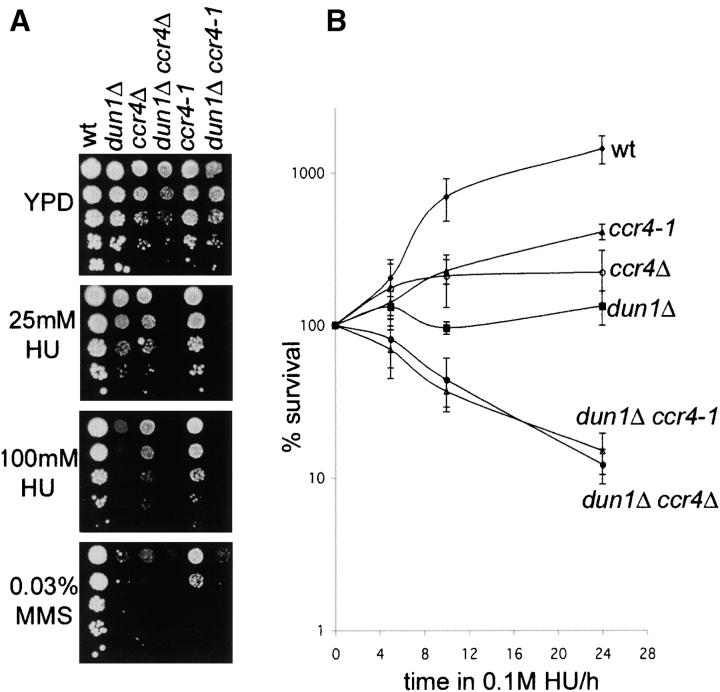

To analyze whether Ccr4-Caf1 deadenylase activity plays a role in the DNA damage response similar to Pan2-Pan3, ccr4Δ and dun1Δ ccr4Δ strains were tested for their ability to grow on plates containing HU or MMS. As shown in Figure 1A, ccr4Δ mutants were sensitive to both agents. Similar to what we observed for Dun1 and Pan2-Pan3, the dun1Δ ccr4Δ double mutants showed a dramatic increase in sensitivity to HU compared to either single mutant, suggesting that CCR4 and DUN1 might act toward the same goal in the cellular response to replication blocks, but provide separate functions. In contrast, the dun1Δ ccr4Δ cells were not synthetically sensitive to MMS (Figure 1A), potentially placing CCR4 and DUN1 in the same genetic pathway that acts upon alkylating DNA damage.

Figure 1.—

DNA damage sensitivity of ccr4Δ and caf1Δ mutants and genetic interaction with dun1Δ. (A) Cells were grown to log phase and 10-fold serial dilutions starting from A600 = 0.5 were spotted on YPD plates with or without HU or MMS. (B) Time course survival assays of the indicated strains in 100 mm HU. Aliquots were taken immediately before and every 4 hr after addition of HU and plated on YPD plates. Viable colonies were counted after 3 days of growth and survival was determined on the basis of numbers of colonies before HU addition. Error bars represent the standard deviation. wt, wild type.

Caf1 is physically close to Ccr4 in the Ccr4-Not complex and the respective mutants have many phenotypes in common, including mRNA deadenylation defects (Tucker et al. 2001; reviewed in Collart 2003). We therefore tested the ability of caf1Δ cells to respond to DNA damage. CAF1-deleted cells showed even higher sensitivity to HU than did ccr4Δ mutants and were also mildly sensitive to MMS (Figure 1A). Similar to dun1Δ ccr4Δ, dun1Δ caf1Δ mutants showed synthetic sensitivity on HU plates. However, unlike dun1Δ ccr4Δ, dun1Δ caf1Δ cells were also more sensitive to MMS than were the respective single mutants (Figure 1A).

Impaired colony formation on plates containing DNA-damaging agents could reflect growth defects or an inability of the mutants to survive upon damage to the genome. To distinguish between these possibilities, we assayed the dun1Δ, ccr4Δ, dun1Δ ccr4Δ, caf1Δ, and dun1Δ caf1Δ strains for their ability to survive exposure to HU over a 24-hr time course. As shown in Figure 1B, the wild type could proliferate even in the presence of 0.1 m HU. dun1Δ, ccr4Δ, and caf1Δ mutants did not multiply, but remained viable, as >65% of the cells were able to form colonies on YPD plates after being removed from HU. In contrast, for the dun1Δ ccr4Δ and dun1Δ caf1Δ double mutants only 1–5% of the cells were viable following 24 hr of exposure to HU. These data indicate that the observed synthetic sensitivity of the dun1Δ ccr4Δ and dun1Δ caf1Δ double mutants is due to HU-induced lethality. In other words, although Ccr4-Caf1 and Dun1 are required for cellular proliferation in the presence of replication blocks, only when Ccr4-Caf1 and Dun1-dependent functions are simultaneously deleted is exposure to HU actually lethal for the cells. Therefore, both Ccr4-Caf1 and Dun1 perform critical roles in survival after replication stress.

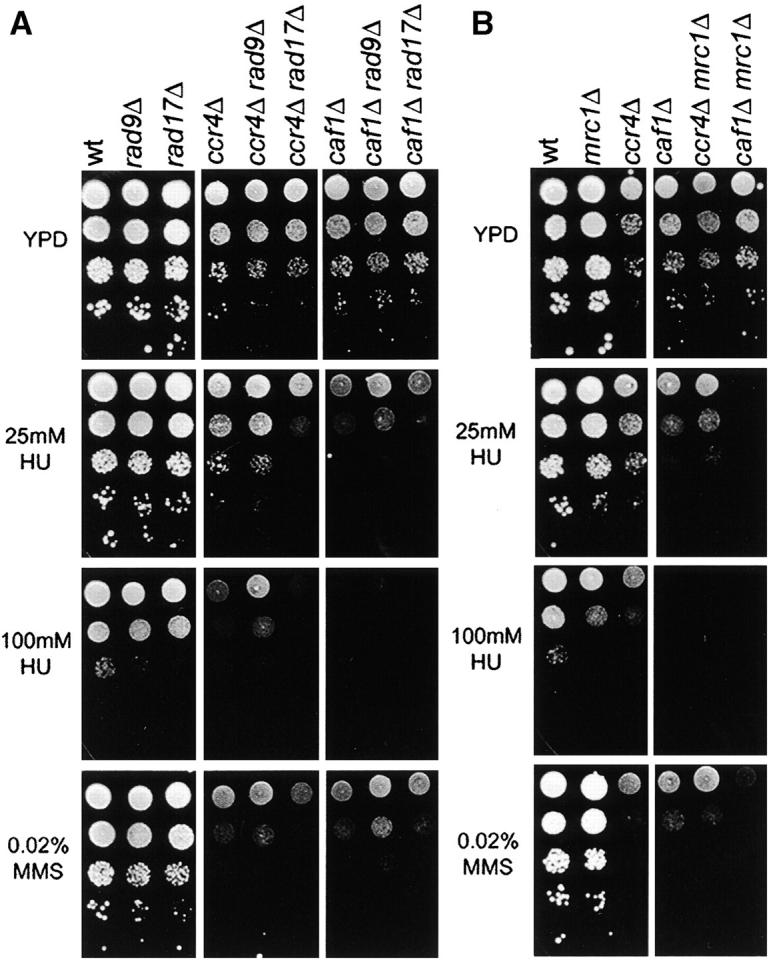

Complex genetic interactions of CCR4 and CAF1 with checkpoint mediators Rad9, Rad17, and Mrc1:

To further explore the role of Ccr4 and Caf1 in the DNA damage checkpoint response we performed similar double-mutant analyses of ccr4Δ and caf1Δ mutants with deletions of the checkpoint genes RAD9, RAD17, or MRC1. As shown in Figure 2A, deletion of RAD17 increased the sensitivity of ccr4Δ mutants on HU and also less severely on MMS, but had no effect on caf1Δ cells. In contrast, rad9Δ surprisingly led to moderately improved growth of ccr4Δ and caf1Δ strains on HU and, in the case of caf1Δ, also on MMS (Figure 2A). Deletion of MRC1 in ccr4Δ or caf1Δ mutants mimicked the deletion of DUN1, in that both ccr4Δ mrc1Δ and caf1Δ mrc1Δ double mutants were more sensitive than the single mutants to HU, but only caf1Δ mrc1Δ also showed synthetic sensitivity to MMS (Figure 2B). The observed interactions with checkpoint proteins confirm that Ccr4 and Caf1 have a role in checkpoint pathways activated by DNA damage and replication blocks.

Figure 2.—

Genetic interactions of CCR4 and CAF1 with RAD9, RAD17, and MRC1. Double deletion mutants of rad9Δ, rad17Δ (A), and mrc1Δ (B) with ccr4Δ or caf1Δ were assayed for their sensitivity to HU and MMS and compared to the respective single mutants. Cells were grown in YPD to log phase, diluted, and spotted onto YPD plates with or without 25 or 100 mm HU or 0.02% MMS and the plates were photographed after 3 days of growth at 30°. wt, wild type.

Ccr4 exonuclease activity is involved in the DNA damage response and genetic interaction with DUN1:

To analyze the contribution of the deadenylase activity of Ccr4 to the DNA damage response, we introduced the E556A mutation into the genomic CCR4 locus. Mutation of the E556 catalytic residue abrogates deadenylation activity of Ccr4 in vivo and in vitro (Chen et al. 2002). The E556A change does not disrupt the stability of Ccr4 (Chen et al. 2002) and, in agreement with that, the ccr4 E556A (ccr4-1) strain had better growth properties than ccr4Δ under basal conditions (Figure 3A control plate). However, with respect to DNA damage sensitivity, the exonuclease mutant behavior was similar to that in the deletion strain: it was sensitive to HU and MMS and in combination with dun1Δ was synthetically sensitive to HU, but not to MMS (Figure 3A). We also performed quantitative survival assays in liquid 0.1 m HU cultures over a 24-hr time course (Figure 3B). In these assays, the ccr4-1 catalytic domain mutant had slightly better proliferation properties than the ccr4Δ strain, but the HU survival rates of the dun1Δ ccr4-1 double mutant were indistinguishable from those of dun1Δ ccr4Δ (Figure 3B), indicating that loss of mRNA exonuclease activity is responsible for the genetic interactions of ccr4Δ with dun1Δ. Altogether, the identical synthetic HU hypersensitivity of dun1Δ ccr4-1 compared to dun1Δ ccr4Δ (Figure 3, A and B) and similar MMS hypersensitivity of ccr4-1 compared to ccr4Δ (Figure 3A) demonstrate that Ccr4 mRNA deadenylase activity plays a critical role in response to DNA damage.

Figure 3.—

Inactivation of the exonuclease activity of Ccr4 leads to DNA damage sensitivity. (A) Survival assays of ccr4Δ, ccr4-1, ccr4Δ dun1Δ, and ccr4-1 dun1Δ cells on HU and MMS plates as described for Figure 1A. (B) Time course survival assays in HU as in Figure 1B. wt, wild type.

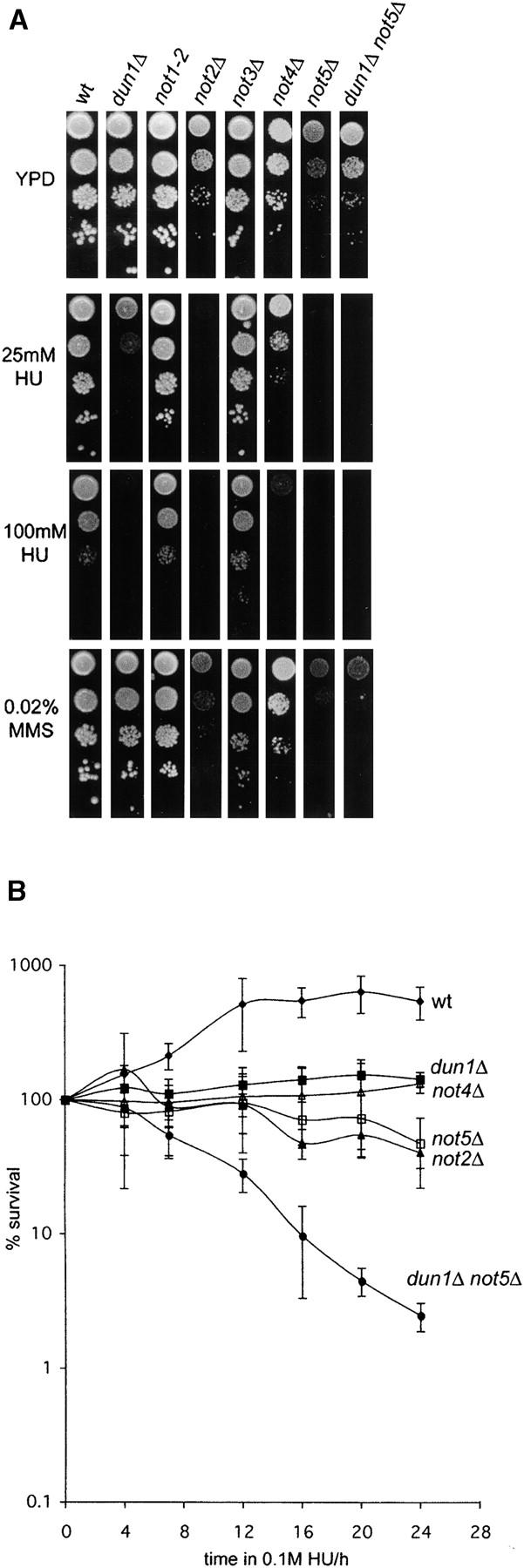

Contributions of transcriptional functions of the Ccr4-Not complex to the DNA damage response:

Although Ccr4 is the catalytic subunit, Caf1 is believed to be equally important for mRNA deadenylase activity of the Ccr4-Not complex in vivo (Tucker et al. 2001). Considering that the results with the ccr4-1 catalytic domain mutant strongly support the involvement of Ccr4-Caf1 mRNA deadenylase functions in the DNA damage response, it was surprising that ccr4Δ and caf1Δ differed in some of their DNA damage-sensitivity phenotypes. For example, caf1Δ is more HU hypersensitive than ccr4Δ (Figures 1 and 2) and compared to ccr4Δ has different synthetic interactions in response to MMS with dun1Δ and in response to low-dose HU treatment with mrc1Δ (Figure 2B). A possible explanation to resolve this paradox was that nondeadenylase functions of the Ccr4-Not complex could also contribute to the DNA damage response. The main role of the Not proteins is believed to be in the regulation of transcription through modulation of the function of the general transcription factor TFIID (reviewed in Collart 2003), and the respective mutants show only very subtle defects in mRNA deadenylation (Tucker et al. 2002).

Therefore, to investigate if the transcriptional functions of the complex could also be involved in the DNA damage response, we analyzed the DNA damage sensitivity of not1-2, not2Δ, not3Δ, not4Δ and not5Δ mutants. In plate assays, NOT2, NOT4, and NOT5 were required for normal cell growth in the presence of HU and, in the case of NOT5, also in the presence of MMS, while not1-2 and not3Δ mutants had normal growth properties under these conditions (Figure 4A). In 24-hr HU survival experiments, not2Δ, not4Δ, and not5Δ strains showed a phenotype similar to that of ccr4Δ and caf1Δ (Figure 1B) in that they did not proliferate but remained largely viable (Figure 4B). Similar to ccr4Δ and caf1Δ (Figure 1B), not5Δ exhibited a dramatic synthetic lethality phenotype in concert with dun1Δ in response to HU (Figure 4B). Together with some discrepant DNA damage-sensitivity phenotypes between ccr4Δ and caf1Δ (Figures 1 and 2), these data support the notion that deadenylase-independent functions of the Ccr4-Not complex contribute to the DNA damage response, most likely involving its established role in the regulation of transcription.

Figure 4.—

Role of Not proteins in the DNA damage response. (A) Log phase cultures of wild-type or mutant strains were diluted and spotted on YPD plates with or without 25 or 100 mm HU or 0.02% MMS. not2Δ, not5Δ, and dun1Δ not5Δ strains were grown for 5 days before pictures were taken. All other strains were photographed after 3 days. (B) Survival after prolonged exposure to HU was measured as described for Figure 1B. wt, wild type.

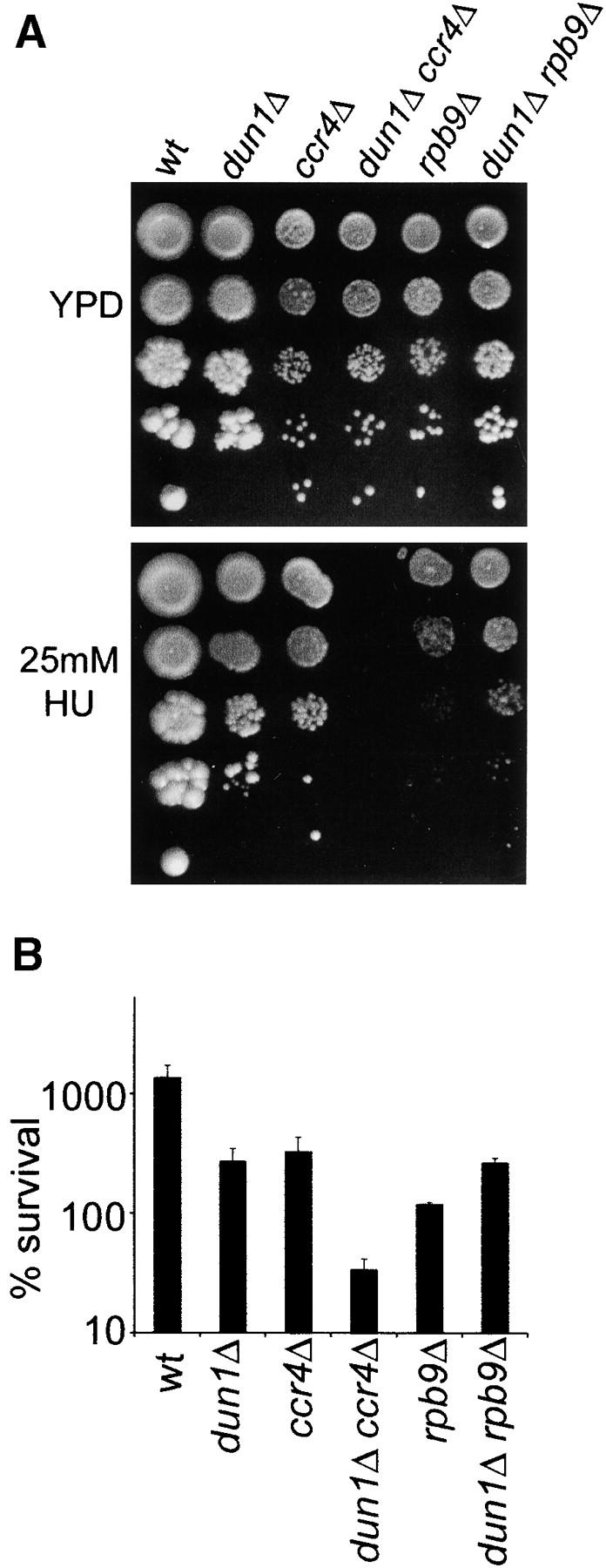

The involvement of Ccr4-Not in multiple aspects of gene expression opens the possibility that disruption of the transcriptional process per se is responsible for the observed DNA damage-sensitivity phenotypes rather than specific functions of this complex. To address the specificity of our results with ccr4-not mutants, we deleted the gene encoding the nonessential RNA polymerase II subunit Rpb9 to analyze DNA damage phenotypes and the genetic interaction with dun1Δ (Figure 5). Rpb9 has been previously shown to be involved in transcription initiation and elongation and transcription-coupled DNA repair (TCR; Hull et al. 1995; Hemming et al. 2000; Li and Smerdon 2002), and rpb9Δ mutants are hypersensitive to MMS and γ-irradiation (Bennett et al. 2001; Chang et al. 2002). As expected, rpb9Δ cells showed impaired growth properties on HU plates, but in contrast to ccr4Δ they did not exhibit a synthetic sensitivity phenotype with dun1Δ (in fact, dun1Δ partially suppressed the HU growth defect phenotype of rpb9Δ, suggesting that Dun1-dependent checkpoint functions may be involved in delaying cell cycle progression in the presence of DNA lesions that are normally repaired by TCR)(Figure 5A). Liquid survival assays indicated that the growth defect of rpb9Δ cells was fully reversible even after 24 hr in 100 mm HU, and again rpb9Δ and dun1Δ were not synthetic lethal under these conditions (Figure 5B). Therefore, these results indicate that the genetic interactions between Ccr4-Not components and the Dun1 checkpoint kinase are specific for the functions of these proteins and not simply due to nonspecific effects of impaired transcription.

Figure 5.—

Analysis of HU sensitivity of the rpb9Δ strain and its genetic interaction with dun1Δ. (A) Drop tests on HU-containing plates were done as in Figure 1A. Cells were photographed after 5 days of growth. (B) Survival after 24 hr in HU was determined as in Figure 1B. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

The HU sensitivity of ccr4 and caf1 mutants is independent of regulation of ribonucleotide reductase:

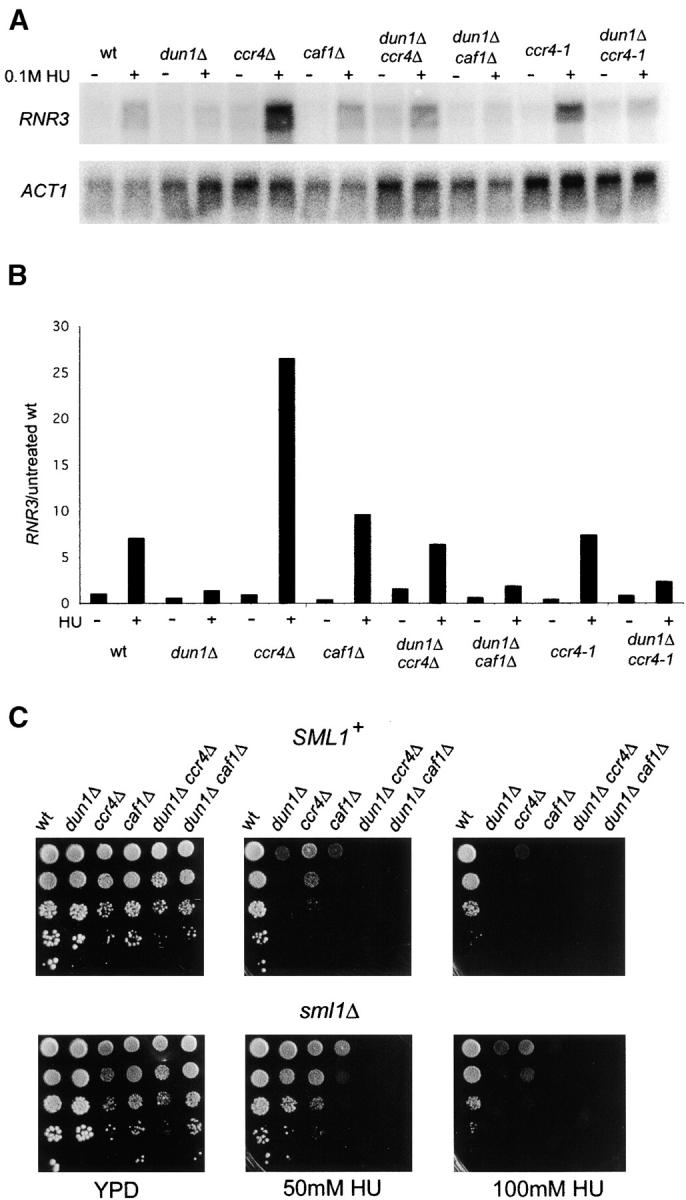

HU causes replication blocks by inhibiting RNR, the enzyme required for biosynthesis of dNTPs. Therefore, one of the tasks of the replication checkpoint activated upon HU treatment is to increase the activity of RNR. This is achieved by Mec1-Rad53-Dun1 dependent transcriptional induction of genes coding for RNR subunits, such as RNR3 (Zhou and Elledge 1993; Huang et al. 1998), phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of the RNR inhibitor Sml1 (Zhao et al. 2001; Zhao and Rothstein 2002) and by regulation of the subcellular localization of RNR subunits between the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Yao et al. 2003). Since the Ccr4-Not complex functions in gene expression, a plausible explanation for the observed sensitivity of ccr4Δ, dun1Δ ccr4Δ, caf1Δ, and dun1Δ caf1Δ mutants to HU was that they cannot induce RNR genes upon replication stress. We hence tested if RNR3 was a target of Ccr4-Not. As expected dun1Δ cells were not able to significantly induce RNR3 after treatment with HU (Figure 6, A and B). However, ccr4Δ and caf1Δ were proficient in transcribing RNR3 upon replication stress, with ccr4Δ mutants showing even three to four fold higher levels of RNR3 expression in HU than the wild type (Figure 6, A and B). Moreover, deletion of CCR4, but not CAF1, restored the ability of dun1Δ cells to produce RNR3 mRNA upon replication stress at almost wild type levels (dun1Δ ccr4Δ +HU samples in Figure 6, A and B). Interestingly, although the ccr4-1 exonuclease domain mutant had DNA damage phenotypes similar to the complete deletion, it did not lead to increased HU-induced RNR3 expression by itself nor restoration of HU-induced RNR3 expression in dun1Δ cells (Figure 6, A and B).

Figure 6.—

Ccr4 and Caf1 are not required for expression of RNR3 upon replication stress. (A) RNR3 expression in the indicated strains was analyzed before and after treatment with 0.1 m HU for 3 hr. ACT1 mRNA levels were used as loading control. (B) RNR3 levels were normalized to ACT1 levels and then expressed as fold difference compared to basal levels of expression in the wild type. (C) Analysis of the effect of sml1Δ on DNA damage sensitivity of dun1Δ, ccr4Δ, dun1Δ ccr4Δ, caf1Δ, and dun1Δ caf1Δ strains was done as described for Figure 1A. wt, wild type.

Deletion of SML1 suppresses the phenotypes of checkpoint mutants that are associated with the inability to up-regulate RNR activity (Zhao et al. 1998). Therefore, another way of assessing whether lower RNR activity is the cause for the sensitivity of ccr4Δ, dun1Δ ccr4Δ, caf1Δ, and dun1Δ caf1Δ mutants to HU is to look at suppression effects of deleting SML1. As shown in Figure 6C, sml1Δ was able to partially suppress ccr4Δ and caf1Δ growth defects on HU plates, but it did not suppress the synthetic HU hypersensitivity of dun1Δ ccr4Δ and dun1Δ caf1Δ strains.

Collectively, these data indicate that the compromised activity of RNR upon treatment with HU is not the reason for the hypersensitivity of ccr4Δ, dun1Δ ccr4Δ, caf1Δ, and dun1Δ caf1Δ mutants to replication blocks.

Prolonged Rad53 activation in dun1Δ ccr4Δ mutants:

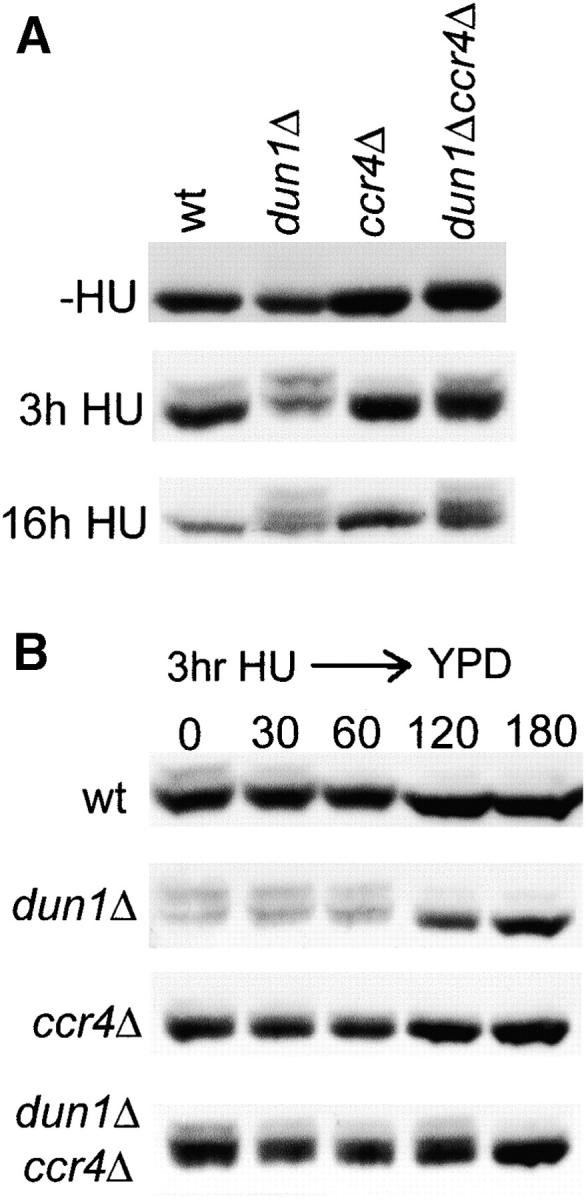

To test if the severe sensitivity of dun1Δ ccr4Δ mutants to HU could be a consequence of impaired checkpoint signaling, we analyzed Rad53 activation and inactivation kinetics in these strains. Rad53 is activated by phosphorylation that can be detected as slower mobility bands by Western blot analysis (Pellicioli et al. 1999), and in response to replication blocks the relative amount of shifted Rad53 correlates with the strength of the checkpoint signal (Pike et al. 2004). In dun1Δ and dun1Δ ccr4Δ strains Rad53 was hyperphosphorylated compared to the wild type after 3 hr of 100 mm HU treatment, as well as after 16 hr HU treatment (Figure 7A). These data indicate that the increased HU lethality of dun1Δ ccr4Δ (Figure 1) is not the result of checkpoint failure. Interestingly, Rad53 activation was slightly reduced in ccr4Δ compared to the wild type (Figure 7A), presumably because higher RNR3 levels in this strain (Figure 6, A and B) lead to reduced replicative damage in response to the same dose of HU.

Figure 7.—

Rad53 phosphorylation in dun1Δ, ccr4Δ, and dun1Δ ccr4Δ mutants. (A) Western blot analysis of Rad53 under basal conditions (−HU) and after 3 and 16 hr of 100 mm HU treatment in the indicated strains. (B) Western blot analysis of Rad53 before (0) and 30, 60, 120, and 180 min after release from 100 mm HU for 3 hr into HU-free YPD medium.

Given that Rad53 was hyperphosphorylated in dun1Δ and dun1Δ ccr4Δ, it was possible that the decreased ability of the double mutant to form colonies after release from HU (Figure 1B) is the result of permanent cell cycle arrest due to irreversible checkpoint activation. To test this possibility, we monitored Rad53 inactivation in these strains after release from HU into normal medium (Figure 7B). In the wild type, the original Rad53 shift was approximately 50% reduced after 30 min and fully reversed after 1 hr. In contrast, Rad53 inactivation was delayed by 1 hr in the dun1Δ mutant and by another hour in the dun1Δ ccr4Δ double mutant (Figure 7B). These data indicate that dun1Δ ccr4Δ cells are significantly impaired in reversing checkpoint activation in the recovery from replication stress, but they are nevertheless able to fully turn off the checkpoint signal within 3 hr after HU release. As the 1-hr delay in Rad53 inactivation in dun1Δ ccr4Δ cells compared to dun1Δ (or 2 hr compared to wild type) would have only a minor effect on colony growth on HU-free plates after 3 days (Figure 1B), these results indicate that the increased HU-dependent lethality of the double mutant is not the result of a checkpoint recovery defect.

DISCUSSION

In this report we have shown that the exonuclease activity of the Ccr4-Caf1 mRNA deadenylase complex plays an important role in the cellular response to replicative DNA damage, in a manner that is synergistic with the Dun1 checkpoint kinase (Figures 1 and 3). Since the catalytic subunit Ccr4 and the noncatalytic subunit Caf1 are both essential for mRNA deadenylase activity of this complex (Tucker et al. 2001), deletion of either subunit should have the same DNA damage-hypersensitivity effects. However, although ccr4Δ and caf1Δ mutants behaved overall in a similar manner, we found a number of important differences in their DNA damage-sensitivity profiles and synthetic genetic interactions with checkpoint genes (Figures 1 and 2). These discrepancies indicated that mRNA deadenylase-independent functions of the complex may also contribute to the DNA damage response. As Ccr4-Caf1 is part of the Ccr4-Not complex that functions in transcriptional regulation of gene expression in addition to mRNA deadenylation, we analyzed the role of other Not complex components in the DNA damage response and found that not2Δ, not4Δ, and not5Δ also resulted in replication block hypersensitivity and, in the case of not5Δ as an example, in a synthetic phenotype with dun1Δ similar to ccr4Δ or caf1Δ (Figure 4). Altogether, the most straightforward explanation for our findings is that both the transcriptional and the post-transcriptional functions of the Ccr4-Not complex play important functions in the DNA damage response.

A remarkable feature of dun1Δ ccr4Δ, dun1Δ caf1Δ, dun1Δ not5Δ double mutants, as well as double mutants of dun1Δ with a single residue substitution in an exonuclease catalytic residue (ccr4-1), was that they not only failed to grow in the continuous presence of the replication blocking agent HU, but also were unable to recover from replicative damage in survival assays in liquid cultures (Figures 1B, 3B, and 4B). Although dun1Δ ccr4Δ mutants were considerably delayed in reversing HU-induced Rad53 phosphorylation as a molecular marker for checkpoint activation, they were able to inactivate Rad53 within 3 hr of release from HU (Figure 7B). This indicates that dun1Δ ccr4Δ cells were able to process the checkpoint-activating DNA lesions into “neutral” products that were no longer recognized by the checkpoint machinery, yet were unable to sustain normal cell viability. As dun1Δ cells already have dramatically increased genome instability rates under basal conditions (Myung et al. 2001), a plausible explanation for this phenotype could be that ccr4Δ exacerbates this property of dun1Δ in response to HU by redirecting the repair of replicative DNA damage into inappropriate pathways with extensive genome rearrangements and loss of genetic material and subsequent loss of viability.

Considering its role in gene expression, there are two main possible mechanisms by which defects in the Ccr4-Not complex could affect DNA repair in “presensitized” dun1Δ mutants. First, changes to the transcriptional process per se could affect DNA repair, as damage is known to be more efficiently repaired by the TCR pathway in transcribed genes than in nontranscribed genes. However, in contrast to ccr4Δ, caf1Δ, and not5Δ, deletion of the nonessential RNA polymerase II subunit RBP9, which plays important roles in TCR and also gives rise to transcriptional defects, did not result in a synthetic HU hypersensitivity with dun1Δ. In addition, because the ccr4-1 mutation most likely acts at the post-transcriptional level, a different mechanism seems more likely. This second mechanism could be that loss of some components of the Ccr4-Not complex in concert with dun1Δ leads to complex changes in cellular mRNA profiles that adversely affect the repair of replicative DNA lesions by shifting the equilibrium between opposing DNA repair pathways. A similar mechanism has been invoked in the case of the related dun1Δ pan2Δ or dun1Δ pan3Δ phenotypes, where the increased replication block sensitivity could be attributed to increased RAD5 expression (Hammet et al. 2002), but here we did not find significantly elevated RAD5 mRNA levels in dun1Δ ccr4Δ strains (data not shown). Surprisingly, we found that HU-induced expression of RNR3 was actually increased in ccr4Δ mutants (Figure 6), which should reduce the number of stalled replication forks; yet, despite presumably fewer lesions, this mutation resulted in HU hypersensitivity. With two candidate “culprits” ruled out, it will be interesting to see in more comprehensive array experiments how the expression of DNA repair genes is affected in mutants of the Ccr4-Not complex.

As already mentioned, ccr4-not mutants have been identified as sensitive to DNA damage induced by UV, ionizing radiation (IR), HU, MMS, and other DNA-damaging agents in several large-scale studies (Bennett et al. 2001; Hanway et al. 2002; Westmoreland et al. 2004). Some differences between these reports and our data are probably due to strain differences, use of diploid vs. haploid strains, and different DNA-damaging agents and conditions. Diploid not3Δ cells were reported to be IR hypersensitive (Westmoreland et al. 2004), whereas haploids are not hypersensitive to HU or MMS (Figure 5). Also, we found that although the mutants in the NOT genes were sensitive to UV, ccr4Δ and caf1Δ were not (data not shown). Westmoreland et al. (2004) also showed that diploid ccr4Δ cells have an extended RAD9-dependent cell cycle arrest after IR. The Rad9 pathway is not usually activated by replication blocks, but can be indirectly activated if primary replicative damage is processed into lesions that are sensed by the cell cycle-wide DNA damage pathways (Pike et al. 2004). Rad9 could therefore also contribute to Rad53 hyperphosphorylation and delayed recovery after HU release in dun1Δ and dun1Δ ccr4Δ cells (Figure 7), although deletion of RAD9 improved growth of ccr4Δ and caf1Δ cells in the continuous presence of HU and MMS only very modestly (Figure 2A). Our results extend the findings of the large-scale screens by establishing that the mRNA deadenylase function of Ccr4-Not is involved in the DNA damage response and by comprehensively analyzing the genetic interactions of the complex with the alternate checkpoint pathways. In addition, our data suggest that the role of Ccr4-Not complex in DNA damage responses also involves mRNA deadenylase-independent functions, mostly likely related to its functions in the regulation of transcription. Not4, a subunit that we found was required for HU tolerance, is a potential ubiquitin ligase (Albert et al. 2002) and therefore this activity could be another means for Ccr4-Not to influence the DNA damage response, in a manner dependent or independent of its roles in transcription and mRNA turnover.

It is established that pathways activated by DNA damage target gene expression, and it is becoming more and more evident that, in addition to the well-characterized regulation of transcription (Zhou and Elledge 1993; Huang et al. 1998; Gasch et al. 2001), the DNA damage response also works by modulating post-transcriptional events in mRNA physiology. Emerging examples of post-transcriptional factors with links to the DNA damage response include the mammalian mRNA polyadenylation factor CstF (Kleiman and Manley 2001), the cytoplasmic Schizosaccharomyces pombe poly(A) polymerase Cid13 (Saitoh et al. 2002), the budding yeast poly(A) nuclease complex Pan2-Pan3 (Hammet et al. 2002), and now the Ccr4-Caf1 mRNA deadenylase complex. A question that is still unanswered is how post-transcriptional events in the cytoplasm are targeted by the DNA damage response, since the major components of checkpoint signaling pathways reside in the nucleus. Ccr4-Not could play a role in physically connecting these two processes via its dual role in both nuclear transcription and cytoplasmic mRNA turnover. The relation between these two functions of Ccr4-Not it is not yet clear, but it has been proposed that the interaction with the transcription machinery enables Ccr4-Not to associate cotranscriptionally with mRNA, before its export to the cytoplasm (Tucker et al. 2001). In such a way, the Ccr4-Not complex could enable the DNA damage signal to be transferred from the nucleus to the cytoplasm to act there in the post-transcriptional regulation of mRNA stability. This way, simultaneous targeting of nuclear transcriptional functions and cytoplasmic post-transcriptional functions of the Ccr4-Not complex by the checkpoint machinery could provide a means to facilitate a rapid switch in cellular mRNA profiles to adapt to the complex changes required for an efficient DNA damage response.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brietta Pike for critical reading of the manuscript and discussions. This work was supported by a project grant and a senior research fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (to J.H.), a Cancer Council Victoria Postdoctoral Fellowship (to A.H.), and National Institutes of Health grants GM41215 and USDA291H (to C.L.D.).

References

- Albert, T. K., H. Hanzawa, Y. I. Legtenberg, M. J. de Ruwe, F. A. van den Heuvel et al., 2002. Identification of a ubiquitin-protein ligase subunit within the CCR4-NOT transcription repressor complex. EMBO J. 21: 355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcasabas, A. A., A. J. Osborn, J. Bachant, F. Hu, P. J. Werler et al., 2001. Mrc1 transduces signals of DNA replication stress to activate Rad53. Nat. Cell. Biol. 3: 958–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badarinarayana, V., Y. C. Chiang and C. L. Denis, 2000. Functional interaction of CCR4-NOT proteins with TATAA-binding protein (TBP) and its associated factors in yeast. Genetics 155: 1045–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y., C. Salvadore, Y. C. Chiang, M. A. Collart, H. Y. Liu et al., 1999. The CCR4 and CAF1 proteins of the CCR4-NOT complex are physically and functionally separated from NOT2, NOT4, and NOT5. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 6642–6651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashkirov, V. I., J. S. King, E. V. Bashkirova, J. Schmuckli-Maurer and W. D. Heyer, 2000. DNA repair protein Rad55 is a terminal substrate of the DNA damage checkpoints. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 4393–4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C. B., L. K. Lewis, G. Karthikeyan, K. S. Lobachev, Y. H. Jin et al., 2001. Genes required for ionizing radiation resistance in yeast. Nat. Genet. 29: 426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. E., and A. B. Sachs, 1998. Poly(A) tail length control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae occurs by message-specific deadenylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 6548–6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M., M. Bellaoui, C. Boone and G. W. Brown, 2002. A genome-wide screen for methyl methanesulfonate-sensitive mutants reveals genes required for S phase progression in the presence of DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 16934–16939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Y. C. Chiang and C. L. Denis, 2002. CCR4, a 3′-5′ poly(A) RNA and ssDNA exonuclease, is the catalytic component of the cytoplasmic deadenylase. EMBO J. 21: 1414–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart, M. A., 2003. Global control of gene expression in yeast by the Ccr4-Not complex. Gene 313: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugeron, M. C., F. Mauxion and B. Seraphin, 2001. The yeast POP2 gene encodes a nuclease involved in mRNA deadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 2448–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis, C. L., and J. Chen, 2003. The CCR4-NOT complex plays diverse roles in mRNA metabolism. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 73: 221–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis, C. L., Y. C. Chiang, Y. Cui and J. Chen, 2001. Genetic evidence supports a role for the yeast CCR4-NOT complex in transcriptional elongation. Genetics 158: 627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durocher, D., and S. P. Jackson, 2002. The FHA domain. FEBS Lett. 513: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdeniz, N., U. H. Mortensen and R. Rothstein, 1997. Cloning-free PCR-based allele replacement methods. Genome Res. 7: 1174–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R., C. W. Putnam and T. Weinert, 1999. RAD53, DUN1 and PDS1 define two parallel G2/M checkpoint pathways in budding yeast. EMBO J. 18: 3173–3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch, A. P., M. Huang, S. Metzner, D. Botstein, S. J. Elledge et al., 2001. Genomic expression responses to DNA-damaging agents and the regulatory role of the yeast ATR homolog Mec1p. Mol. Biol. Cell 12: 2987–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammet, A., B. L. Pike, K. I. Mitchelhill, T. Teh, B. Kobe et al., 2000. FHA domain boundaries of the Dun1p and Rad53p cell cycle checkpoint kinases. FEBS Lett. 471: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammet, A., B. L. Pike and J. Heierhorst, 2002. Posttranscriptional regulation of the RAD5 DNA repair gene by the Dun1 kinase and the Pan2-Pan3 poly(A)-nuclease complex contributes to survival of replication blocks. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 22469–22474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammet, A., B. L. Pike, C. J. McNees, L. A. Conlan, N. Tenis et al., 2003. FHA domains as phospho-threonine binding modules in cell signaling. IUBMB Life 55: 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanway, D., J. K. Chin, G. Xia, G. Oshiro, E. A. Winzler et al., 2002. Previously uncharacterized genes in the UV- and MMS-induced DNA damage response in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 10605–10610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemming, S. A., D. B. Jansma, P. F. Macgregor, A. Goryachev, J. D. Friesen et al., 2000. RNA polymerase II subunit Rpb9 regulates transcription elongation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 35506–35511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M., Z. Zhou and S. J. Elledge, 1998. The DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways induce transcription by inhibition of the Crt1 repressor. Cell 94: 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull, M. W., K. McKune and N. A. Woychik, 1995. RNA polymerase II subunit RPB9 is required for accurate start site selection. Genes Dev. 19: 481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman, F. E., and J. L. Manley, 2001. The BARD1-CstF-50 interaction links mRNA 3′ end formation to DNA damage and tumor suppression. Cell 104: 743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, T., T. Wakayama, T. Naiki, K. Matsumoto and K. Sugimoto, 2001. Recruitment of Mec1 and Ddc1 checkpoint proteins to double-strand breaks through distinct mechanisms. Science 294: 867–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, C., S. E. Lee, M. B. Vaze, F. Ochsenbien, R. Guerois et al., 2003. PP2C phosphatases Ptc2 and Ptc3 are required for DNA checkpoint inactivation after a double-strand break. Mol. Cell 11: 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., and M. J. Smerdon, 2002. Rpb4 and Rpb9 mediate subpathways of transcription-coupled DNA repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 21: 5921–5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhese, M. P., M. Clerici and G. Lucchini, 2003. The S-phase checkpoint and its regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 532: 41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillet, L., C. Tu, Y. K. Hong, E. O. Shuster and M. A. Collart, 2000. The essential function of Not1 lies within the Ccr4-Not complex. J. Mol. Biol. 303: 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, J. A., J. Cohen and D. P. Toczyski, 2001. Two checkpoint complexes are independently recruited to sites of DNA damage in vivo. Genes Dev. 15: 2809–2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung, K., A. Datta and R. D. Kolodner, 2001. Suppression of spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements by S phase checkpoint functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 104: 397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, K. A., R. J. Michelson, C. W. Putnam and T. A. Weinert, 2002. Toward maintaining the genome: DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36: 617–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, A. J., and S. J. Elledge, 2003. Mrc1 is a replication fork component whose phosphorylation in response to DNA replication stress activates Rad53. Genes Dev. 17: 1755–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R., and H. Song, 2004. The enzymes and control of eukaryotic mRNA turnover. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11: 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, A. B., R. L. Brost, H. Ding, Z. Li, C. Zhang et al., 2004. Integration of chemical-genetic and genetic interaction data links bioactive compounds to cellular target pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 22: 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicioli, A., C. Lucca, G. Liberi, F. Marini, M. Lopes et al., 1999. Activation of Rad53 kinase in response to DNA damage and its effect in modulating phosphorylation of the lagging strand DNA polymerase. EMBO J. 18: 6561–6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike, B. L., A. Hammet and J. Heierhorst, 2001. Role of the N-terminal forkhead-associated domain in the cell cycle checkpoint function of the Rad53 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 14019–14026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike, B. L., S. Yongkiettrakul, M. D. Tsai and J. Heierhorst, 2003. Diverse but overlapping functions of the two forkhead-associated (FHA) domains in Rad53 checkpoint kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 30421–30424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike, B. L., N. Tenis and J. Heierhorst, 2004. Rad53 kinase activation-independent replication checkpoint function of the N-terminal forkhead-associated (FHA1) domain. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 39636–39644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J., and S. P. Jackson, 2002. Lcd1p recruits Mec1p to DNA lesions in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell 9: 857–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh, S., A. Chabes, W. H. McDonald, L. Thelander, J. R. Yates et al., 2002. Cid13 is a cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase that regulates ribonucleotide reductase mRNA. Cell 109: 563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, Y., J. Bachant, H. Wang, F. Hu, D. Liu et al., 1999. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by Chk1 and Rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science 286: 1166–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M. F., J. K. Duong, Z. Sun, J. S. Morrow, D. Pradhan et al., 2002. Rad9 phosphorylation sites couple Rad53 to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA damage checkpoint. Mol. Cell 9: 1055–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thore, S., F. Mauxion, B. Seraphin and D. Suck, 2003. X-ray structure and activity of the yeast Pop2 protein: a nuclease subunit of the mRNA deadenylase complex. EMBO Rep. 4: 1150–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, M., M. A. Valencia-Sanchez, R. R. Staples, J. Chen, C. L. Denis et al., 2001. The transcription factor associated Ccr4 and Caf1 proteins are components of the major cytoplasmic mRNA deadenylase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 104: 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, M., R. R. Staples, M. A. Valencia-Sanchez, D. Muhlrad and R. Parker, 2002. Ccr4p is the catalytic subunit of a Ccr4p/Pop2p/Notp mRNA deadenylase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 21: 1427–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaze, M. B., A. Pellicioli, S. E. Lee, G. Ira, G. Liberi et al., 2002. Recovery from checkpoint-mediated arrest after repair of a double-strand break requires Srs2 helicase. Mol. Cell 10: 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, P., T. Ohn, Y. C. Chiang, J. Chen and C. L. Denis, 2004. Mouse CAF1 can function as a processive deadenylase/3′-5′ exonuclease in vitro but in yeast the deadenylase function of CAF1 is not required for mRNA poly (A) removal. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 23988–23995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmoreland, T. J., J. R. Marks, Jr., J. A. Olson, E. M. Thompson, M. A. Resnick et al., 2004. Cell cycle progression in G1 and S phases is CCR4 dependent following ionizing radiation or replication stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 3: 430–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, R., Z. Zhang, X. An, B. Bucci, D. L. Perlstein et al., 2003. Subcellular localization of yeast ribonucleotide reductase regulated by the DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 6628–6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., and R. Rothstein, 2002. The Dun1 checkpoint kinase phosphorylates and regulates the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 3746–3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., E. G. Muller and R. Rothstein, 1998. A suppressor of two essential checkpoint genes identifies a novel protein that negatively affects dNTP pools. Mol. Cell 2: 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., A. Chabes, V. Domkin, L. Thelander and R. Rothstein, 2001. The ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1 is a new target of the Mec1/Rad53 kinase cascade during growth and in response to DNA damage. EMBO J. 20: 3544–3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z., and S. J. Elledge, 1993. DUN1 encodes a protein kinase that controls the DNA damage response in yeast. Cell 75: 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, L., and S. J. Elledge, 2003. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 300: 1542–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]