Abstract

Background:

Since 1993, there has been an increase in the number of postgraduate fellowships in minimally invasive and gastrointestinal (GI) surgery; from 9 in 1993 to more than 80 in 2004. Early on, there was no supervision or accreditation of these fellowships, and they varied widely in content, structure, and quality. This was widely recognized as being a bad situation for fellow applicants and reflected poorly on the specialties of minimally invasive (MI) and GI surgery. In an effort to bring order to this chaotic situation, the Minimally Invasive Surgery Fellowship Council (MISFC) was founded in 1997.

Method:

In 2003, the MISFC was incorporated with 77 founding member programs. The goal of the MISFC was to develop guidelines for high-quality fellowship training, to provide a forum for the directors of MI and GI fellowships to exchange ideas, formulate training curricula; to establish uniform application and selection dates; and to create an equitable computerized match system for applicants.

Results:

In 2004, the MISFC has increased to 95 members representing 154 postgraduate fellowship positions. The majority of these positions are primarily laparoscopic in focus, but other aspects of GI surgery including bariatric, general GI, flexible endoscopy, and hepatopancreatobiliary are also represented. Uniform application and selection dates were agreed on in 2001; and in 2003, the Council established a computerized Match, administered by the National Resident Match Program, which was used for the 2004 fellowship selection. A total of 113 positions were open for the match. A total of 248 applicants formally applied to MISFC programs and 130 participated in the match. Ninety-nine positions matched on the December 10th match day, and the remaining 14 programs successfully filled on the following scramble day. Seventeen applicants did not match to a program. Post match polling of program directors and applicants documented a high degree of compliance, usability, and satisfaction with the process.

Conclusion:

The MISFC has been successful at realizing its goals of bringing order to the past chaos of the MIS and GI fellowship situation. Its current iteration, the Fellowship Council, is in the process of introducing an accreditation process to further ensure the highest quality of postgraduate training in the fields of GI and endoscopic surgery.

The authors describe the history of the MIS Fellowship Council, representing postgraduate training programs in minimally invasive, gastrointestinal, and hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgery. The process of setting up a match process between 130 applicants and the 80 programs (113 positions) is described as well as the results of a post match survey given to program directors and applicants. Ninety-one percent of directors and 83% of applicants were very satisfied with the conduct of the first match in 1994.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has proven to be the signature event that defined the latest era in American surgical education. The availability of a less invasive alternative to one of the most common abdominal surgeries created a nearly instant and universal public demand for it. This necessitated training all surgeons, in training or already practicing, in the application of an unfamiliar technology (laparoscopy). Traditional apprenticeship models were rejected as too slow and inefficient; and new models, mainly short, intensive training courses, including brief didactic and a hands-on animal laboratory, were introduced. A unique partnership between industry and specialty surgical societies, most notably Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgery (SAGES), developed to accomplish the massive volume of training courses needed. Initially rejected by most university based training programs as too radical, it took several years for laparoscopic cholecystectomy to be added to many general surgical residency curricula. Far from being a static event, “lap chole” heralded a continuing process of using ever advancing technology to perform the majority of abdominal surgeries. With the exception of laparoscopic fundoplication, however, adoption of other minimal access procedures has been extremely variable, with laparoscopic champions at some institutions offering a full spectrum and high volume of basic and advanced procedures and other places essentially only doing laparoscopic cholecystectomies. This in turn has created extreme variation in the exposure of residents to these other laparoscopic procedures with the median number of even some common laparoscopic cases (herniorrhaphy, Nissen, appendectomy, ventral hernia) being far below the minimum number needed to pass one's learning curve.1,2 This is not unique to laparoscopic surgery; many disease-based specialties have become so technically enhanced that they are unable to be mastered in the ever shrinking surgical residency training period.3 This has created a demand for post residency training opportunities in a variety of subspecialties, including minimally invasive and GI surgery. A survey administered to fourth and fifth year surgery residents reported that 65% felt that they needed additional training after residency to be competent to practice advanced laparoscopic surgery.4 To satisfy this deficit, many ad hoc “fellowships” in MIS and GI surgery sprang up in the early 1990s. These fellowships were extremely variable in content, intent, and quality of experience. In 1996, in an effort to ensure consistency and quality in these training opportunities, SAGES developed guidelines for a quality Fellowship in surgical endoscopy. The American Board of Surgery actively discouraged SAGES from promulgating these guidelines, and regulation of these programs was tabled by the Society; the American Board of Surgery discouraged publication of guidelines in the fear that they would legitimize the need for postgraduate training in such fundamental components of general surgery (Biester T, American Board of Surgery. personal communication, 2004). In the meantime, the number of such programs had increased from 9 in 1993 to 40 in 1998 and to more than 80 in early 2004.

Recognizing a continued need to provide consistency to existent programs and a forum for fellowship program directors to discuss mutual concerns, a small group of directors began meeting in 1996 and formulated the basics of a council of program directors designed to address these issues and to consider a matching process for fellowship candidates. Specialty societies were still not prepared to confront the establishment by wholly owning this group; therefore, in 2003, the Minimally Invasive Surgery Fellowship Council (MISFC) was independently incorporated as a nonprofit corporation governed by an executive committee and having 40 founding member fellowship programs. Subsequently, the MISFC has grown to more than 95 member programs and represents MIS, GI, bariatric, flexible endoscopy, and hepatobiliary pancreatic fellowships. This makes the MISFC representative of the largest non–ACGME-certified postgraduate fellowships. It is not known absolutely how many fellowship programs do not belong to the MISFC, but it is not likely to be more than 5% to 15% of the total number existing. This gives the MISFC legitimate claim to be the representative group for all such GI and advanced surgery postgraduate training opportunities. In 2003, the MISFC contracted with the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), an independent corporation which manages all medical student/resident matches as well as fellowship matches for colon and rectal, thoracic, vascular, spine, and pediatric surgery, among others, to conduct the first match occurring for the 2004 fellowship year.

METHODS

Fellowship Programs

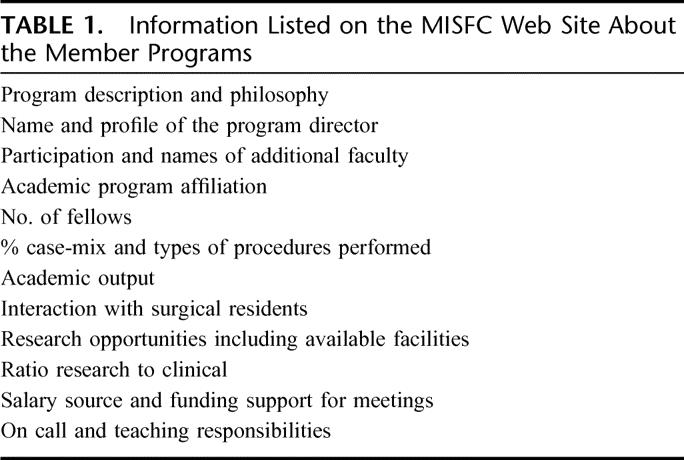

At the time the 2004 match was initiated, the MISFC had 80 member programs in good standing; of these, 77 programs registered 113 postgraduate fellowship positions for the match. Members participating in the match signed an agreement to follow NRMP guidelines on ethical conduct and paid $1000 to register up to 3 positions. Participating programs were listed on the MISFC Web site. These listings included a comprehensive description of each program. The description fields included information intended to allow the resident candidates to assess the strengths and orientation of each program (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Information Listed on the MISFC Web Site About the Member Programs

The listings did not consistently define the fellowship positions by specialty as there is commonly overlap in these programs. In general, the majority had mainly a laparoscopic surgery focus (73%), with bariatric (24%), GI (4%), surgical endoscopy (2%), and hepatobiliary pancreatic (2%) representing a smaller proportion of the total. Fifty percent of programs were based in university programs, 27% in nonuniversity or university-affiliated teaching programs, and 18% were based in community hospitals or were private practice based. Programs with more than one fellow were usually located in academic centers and 48% of programs with a bariatric focus were based in nonteaching hospitals. The majority of programs (64%) were located east of the Mississippi.

Applicants

A fellow application form was available to be completed on line (www//fellowshipcouncil.org). Letters of recommendation were collected centrally at the MISFC office and were sent out to requesting programs. Applicants could apply to 20 programs for a $200 fee, with additional program applications costing $100 per 10 applied to. The deadline for receipt of applications was September 1, 2003. At that date, 248 completed applications had been received. A total of 130 applicants subsequently participated in the match with the remainder not participating presumably because they decided on other career options.

Thirty-nine applicants were foreign medical graduates and 17% were women. The majority were graduating general surgery residents with the rest being surgeons in practice, current Fellows, or other surgical specialists.

Survey

Rank lists were submitted by November 19th, match day was on December 10th, with a post match scramble taking place on Dec 11th. Immediately following the match process, a survey questionnaire was distributed via e-mail to all applicants and program directors participating in the match. The survey consisted of 10 questions and the opportunity for additional comments. Attempts at follow-up of nonresponders were not made. Thirty-three of 77 program directors (43%) responded and 35 applicants (27%) returned theirs.

RESULTS

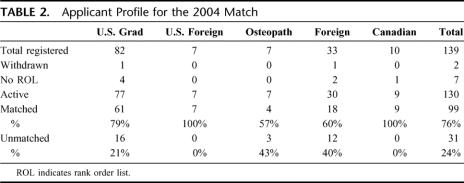

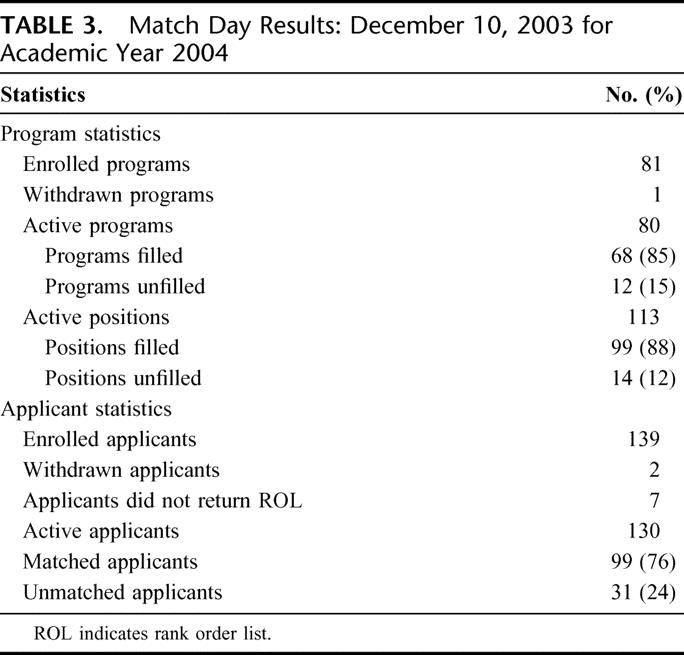

There were 130 applicants hoping to match to the 113 positions offered. Applicants ranked an average of 12 programs (range, 3–42 programs). Ninety-nine applicants (76%) successfully matched on match day. Of the 31 applicants who did not match, 14 found a position on scramble day (Table 2). Sixty-eight fellowship-offering institutions (85%) successfully matched on December 10, 2004. There were 14 positions in 12 programs that failed to match (Table 3). All of these positions were filled on scramble day and the other 2 filled by internal candidates. Thirty-six percent of programs filled with their first rank choice, 12% with their second choice, 9% with their third choice, and 43% with a candidate ranked 4th or more.

TABLE 2. Applicant Profile for the 2004 Match

TABLE 3. Match Day Results: December 10, 2003 for Academic Year 2004

Of the polled program directors, all responding were completely (91%) or somewhat (9%) satisfied with the process. There was satisfaction with most of the particulars of the process: 91% liked the format of the match, felt the deadlines were appropriate, and felt that the MISFC administrative office was helpful. Eighty-five percent of Program Directors felt that the information on their program listed on the match Web page was adequate to give the applicants a good picture of their program. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 12% of directors felt that the application dues were too high. Opinion was more divided on issues of timing: 51% felt it would be fairest to establish a cutoff date before the rank list submission for the completion of interviews and a slight majority (55%) favored a set interview period (5% suggesting 2 weeks, 79% 2 months, 6% 1 month, and 10% 3–4 months). When asked whether the overall impression was that most applicants and program directors were compliant with the letter and the spirit of the match, 88% replied yes and 12% no, but no one offered any specific instances of contract breach. Most importantly, 100% felt that the match served the interests of their programs and applicants, and all said they will participate in it again.

Applicants were also satisfied (83%) or somewhat satisfied (11%) with the match process overall and most (57%) felt that it made applying for a fellowship position more organized (40% had no opinion as they had no previous experience applying for fellowships). Ninety-seven percent of the participants would participate in the match again. As with the program directors, applicants were uniformly appreciative of the MISFC administrative office and the information on the MISFC Web site (100% completely or somewhat satisfied). There were more suggestions for improvement of the match on behalf of the applicants. Twelve percent of applicants felt the application and match fees were excessive and 25% of applicants felt the application could be improved by allowing more information to be supplied about the applicant and about each program. Seventeen percent of applicants applied to 10 or fewer programs, 56% to 11 to 20, 17% to 21 to 30, and 10% to more than 30 programs. Applicants also frequently mentioned the interview process as a problem. Forty-four percent of respondents interviewed at 5 or fewer programs, 34% at 6 to 10 programs, 20% at 11 to 15 programs, and 2% interviewed at more than 16 programs. A total of 37% of applicants felt that their interviews were not consistent, with formats varying considerably between programs.

Regarding the fairness of the match, 74% of applicants felt the match was fair and unbiased, 20% that it was somewhat fair, and only 6% complained of bias. A total of 11% of applicants said they had made arrangements for a position prior to the match, and 8% said that a program director had tried to get them to commit to a position prior to the match.

DISCUSSION

Fellowships in GI and minimally invasive surgery are highly sought after by graduating surgery residents who feel undertrained in advanced GI and laparoscopic procedures when they finish their training.2 With no supervisory control, however, programs varied widely in terms of quality and content, which made it hazardous for the interested applicant to find the right position. The MISFC was conceived in 1996 as an effort to bring order to this situation as well as to provide a forum for program directors to discuss mutual concerns. Implementing a match has always been one of the primary goals of the MISFC, and this report details the results, from all viewpoints, of the first year of the match.

It was considered critical that, for the match to be a success, it had to have:

The majority of eligible programs participating

Uniform application process dates and deadlines

Professional and organized administration of the application/match process

Minimal, if any, breaches of match etiquette or contract.

This report assesses the success of the match using data maintained by the MISFC management, NRMP match data, and the results of a poll of program directors and applicants that was administered immediately after the 2004 match.

It is unknown how many “Fellowships” in minimally invasive, GI, hepatopancreatobiliary, or bariatric surgery there are in North America. There are currently (January 2005) 96 member programs active in the current Fellowship Council, representing 157 fellowship positions. Aside from the Fellowship Council membership roster, the primary listing of postgraduate training opportunities in GI and endoscopic surgery has been a registry maintained on the SAGES Web site. This was a free and nonreviewed listing which listed, at one point, 90 “fellowship” programs. If this represents the majority of programs in existence at the time, the 2004 match represented 88% participation, definitely establishing that the Fellowship Council has a majority representation of available fellowships. In 2004, 71% of the 1000 graduating chief residents reported that they were planning on taking a postgraduate fellowship of some sort after residency. Sixty-four percent of graduates indicated plans for a “listed” (ACGME approved or having a sanctioned match) fellowship and 15%, or 150, for a not otherwise listed one (presumably the majority of these are MIS, bariatric, GI, or hepatobiliary pancreatic). The 99 North American match participants therefore represented 66% of these unlisted fellowships, making this group second only to cardiothoracic fellowships in popularity.

A major accomplishment of the MISFC match was the establishment of uniform application deadlines, ranking dates and a selection (“match”) day. For the 2003 process, programs had until July 1st to pay their dues and register their participation in the match, including supplying the NRMP with a standardized description of their program to be placed on the NRMP Web site. Applicants could register their application any time from June 15th to September 1st, and the program director could continuously review the list of applicants. Most interviews occurred from late summer until November 1st, although there was no set period defined to start or stop the interview process. By November 19, 2003, both program directors and applicants had to sign on to the NRMP Web site and submit their final “rank listing” of each other; after this date, the lists were unable to be modified and programs and applicants were held by contract to accept the results of the computer match. The results of the matching process were posted on the NRMP Web site at noon on December 10th and were accessible by applicants and program directors at that time. As with all resident matches, the period after the match day is used by applicants who didn't match to a program (in this case 31), to contact the program directors whose program slots failed to fill (14 positions in 12 programs). This “scramble” process was self-reported as successful, with all program directors participating reporting their open slots filled. Unfortunately, 17 applicants, or 13% of those participating in the match, failed to find a position in this process. While there is a general feeling that the match deadlines should be as early as possible (to allow applicants to apply for other specialties if they fail to match), it has proven difficult to move the process substantially earlier; and for the 2004 match (for the 2005 academic year), the dates were not substantially different.

Overall, the programs and applicants were pleased with the administration and conduct of the match. The executive director and management of the MISFC maintained the MISFC Web site, interacted with the NRMP, and were available to handle individual questions or problems on the part of programs or applicants. The management and director received uniform compliments for their role in the match by all polled. The NRMP was also complimented on the smoothness of the match process. This is not too surprising as this organization conducts the resident matches for all ACGME specialties as well as for many postgraduate fellowships, including pediatric, vascular, surgical oncology, and others.

Respondents to the poll mentioned several shortcomings of the application and program forms. While program directors felt that the online program descriptions adequately described their fellowships, 25% of applicants felt that the program descriptions should include more detail, including case numbers, call responsibilities, benefit descriptions, and contact information for previous fellows. In response to this, the MISFC recently revised the applications to include some of this information, including a primary descriptor of the program (laparoscopic, GI, bariatric, surgical endoscopy, etc.). Other information suggested by the applicants, primarily case numbers and the contact information of past fellows, were not included as they were either felt to be unlikely to be accurate or would impinge the privacy of the past fellows. The current system of handling letters of recommendation, where hard copies had to be requested from the administrative office on an individual basis, was considered awkward by the program directors. For future matches, the letters will be available as electronic files, either on the NRMP Web site or as an e-mailed file.

The most common and significant complaint on the part of the applicants was with the interview process. Criticisms included the lack of uniform notification, different interview formats and, the most strongly criticized point, absence of an interview notification deadline. Applicants justifiably complained of traveling for an interview at a program only to have another nearby program offer them an interview weeks to months later, forcing a second, or even a third, expensive trip to be made. To minimize this problem, the MISFC voted to encourage programs to notify applicants that they would be offered an interview by October 1. There was discussion about establishing a formal interview period, but this was considered to be too constraining and did not pass as a vote.

As opposed to the program directors, the applicants had more concern regarding the fairness of the selection process. This may be a natural result of the position applicants find themselves in (chosen versus the choosers) but remains a definite concern of the MISFC. During the 2004 match, one program was identified as having a potential violation of the match process contract by choosing a registered applicant outside of the match. This case was investigated and, although there were extenuating circumstances, the program was sanctioned and placed on probation. It is recognized that a successful and worthwhile matching process requires that all follow the most rigorous ethical standards.

Having successfully completed a match does not, of course, guarantee a high-quality educational experience to the applicant. The MISFC has been concerned about program quality and in 2003 adopted fellowship guidelines that were developed by SAGES and SSAT but, until recently, it had no way of certifying the compliance of member programs. A group informally known as the “Tri-partate Committee” was formed in 2003 by 3 GI societies (SAGES, SSAT, and AHPBA [American Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Association]) with the intention of creating a program accreditation and review process. At the end of 2004, the MISFC combined with the Tri-partate Committee. The new entity that was created was renamed the Fellowship Council. The bylaws of the MISFC were changed to add society representation to the Board of Governors, officially change the name to the Fellowship Council, and create an independent Accreditation Committee that is populated by members of the tri-partate Societies and whose job will be to certify program compliance with accepted quality guidelines. This process, which is expected to take several years to complete, will hopefully result in consistent excellence in postgraduate training and hopefully provide a template for improving residency training as well.

The 2005 match of the new Fellowship Council was completed on December 7, 2004 with 186 applicants applying for 154 positions offered by 95 programs. As with the first match, the 2005 match occurred without major problems. Similar to the first, all positions were filled by a combination of the primary match or the scramble day process. The new accreditation committee of the FC performed its first site survey for program accreditation in April 2005.

CONCLUSION

The first match conducted by the MISFC was uniformly considered to be a success by both the program directors and applicants. Based on the experience of the first year's match, changes in the process have been made to make it more efficient and user friendly. There is no doubt that such a process was needed to bring some order to the chaotic situation of postgraduate training in GI and endoscopic surgery. In the future, the newly mandated Fellowship Council hopes to provide any surgery resident desiring training in advanced MIS, GI, or related disciplines with access to a high-quality postgraduate experience.

Footnotes

The authors represent the Fellowship Council, an independent group of Fellowship program directors incorporated in the state of California and dedicated to graduate and postgraduate training issues in GI, Minimally Invasive, Hepatobiliary/Pancreatic, and Bariatric Surgery. It is sponsored by the major GI Surgery Societies: SAGES, SSAT, AHPBA, and ASBS.

Reprints: Lee Swanstrom, MD, Department of Minimally Invasive Surgery, Legacy Health System, 1040 NW 22nd Ave, Suite 560, Portland, OR 97210. E-mail: lswanstrom@aol.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chung R, Pham Q, Wojtasik L, et al. The laparoscopic experience of surgical graduates in the United States. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1792–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park A, Witzke D, Donnelly M. Ongoing deficits in resident training for minimally invasive surgery. J of Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan MF, Debas HT. Surgical education in the United States: portents for change. Ann Surg. 2004;240:565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rattner DW, Apelgren KN, Eubanks WS. The need for training opportunities in advanced laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1066–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]