Abstract

Objective:

To assess the incidence of biliary complications after right lobe living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) in patients undergoing duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy or Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy reconstruction.

Summary Background Data:

Biliary tract complications remain one of the most serious morbidities following liver transplantation. No large series has yet been carried out to compare the 2 techniques in LDLT. This study undertook a retrospective assessment of the relation between the method of biliary reconstruction used and the complications reported.

Methods:

Between February 1998 and June 2004, 321 patients received right lobe LDLT. Biliary reconstruction was achieved with Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy in 121 patients, duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy in 192 patients, and combined Roux-en-Y and duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy in 8 patients. The number of graft bile duct and anastomosis, mode of anastomosis, use of stent tube, and management of biliary complications were analyzed.

Results:

The overall incidence of biliary complications was 24.0%. Univariate analysis revealed that hepatic artery complications, cytomegalovirus infections, and blood type incompatibility were significant risk factors for biliary complications. The respective incidence of biliary leakage and stricture were 12.4% and 8.3% for Roux-en-Y, and 4.7% and 26.6% for duct-to-duct reconstruction. Duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy showed a significantly lower incidence of leakage and a higher incidence of stricture; however, 74.5% of the stricture was managed with endoscopic treatment.

Conclusions:

The authors found an increase in the biliary stricture rate in the duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy group. Because of greater physiologic bilioenteric continuity, less incidence of leakage, and easy endoscopic access, duct-to-duct reconstruction represents a feasible technique in right lobe LDLT.

To assess the incidence of biliary complications after right lobe living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) in patients undergoing duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy or Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy reconstruction. Duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy showed a significantly lower incidence of leakage and a higher incidence of stricture; however, most of the stricture was managed with endoscopic treatment.

Biliary tract complication remains one of the most serious morbidities following liver transplantation, with an incidence of 10% to 30% in deceased liver transplantation.1–4 It has been reported that the pathogenesis of biliary leakage and stricture in deceased liver transplantation were related to preoperative patient condition, blood type incompatibility, ischemic time, hepatic artery complications, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection.5–9 The published data have also suggested that the frequency of biliary complications is higher in post-living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) compared with deceased liver transplantation.10,11 Major concerns are early leakage and late stricture at the anastomotic site, which are associated with technical, anatomic, or microcirculatory considerations. Particularly in the recipient with “small-for-size” graft or deteriorated preoperative status, early biliary complications readily result in a fatal outcome, and these conditions themselves may increase the risk of complications.

There remains considerable disparity in the reported cases with regard to the incidence of biliary complications after right lobe LDLT, with reported rates ranging from 24% to 60%.11,12–15 In right liver graft, current controversy focuses on the selection between Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy and duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy. Many technical issues, such as the method of dissection, selection of suture and mode, and the use of stenting tube, are still under discussion. Duct-to-duct is currently our standard technique of choice for biliary reconstruction in right lobe LDLT, with the following advantages over Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy: 1) no need for intestinal manipulation, serving as an anatomic barrier to reflux of enteric contents into the biliary tract, and it may theoretically decrease the risk of ascending cholangitis and the morbidity is reduced even when early anastomotic leakage occurs; 2) technically faster and easier than Roux-en-Y; and 3) the physiologic bilioenteric continuity enables good endoscopic access postoperatively.16,17

This report describes surgical trials for biliary reconstruction in 321 consecutive right lobe LDLT, focusing on technical considerations regarding the biliary anatomy on graft, suture mode and stent tube in duct-to-duct/Roux-en-Y biliary reconstructions during long-term follow-up.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between June 1990 and June 2004, 953 patients underwent 1000 LDLTs at Kyoto University Hospital, Kyoto, Japan. Right lobe LDLT was first carried out at our institution in February 1998, and we have since performed 346 right lobe LDLTs. Of these, 25 patients died within 3 months of LDLT and are thus excluded from this study. A total of 321 patients were the subjects of the present study.

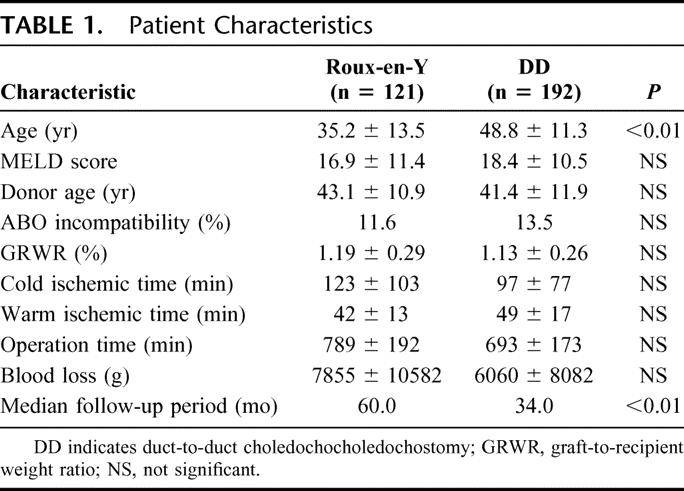

The patients were 164 males and 157 females, with a median age of 43.4 years (range, 15.5–70.3 years), and a median weight of 59.9 kg (range, 34.6–99.5 kg). Median model for end-stage liver disease18 score was 18.0. The indication for liver transplantation was hepatocellular carcinoma in 86 patients, followed by viral hepatitis (n = 57), cholestatic liver disease (n = 57), fulminant hepatic failure (n = 39), biliary atresia (n = 34), metabolic liver disease (n = 9), metastatic liver tumor (n = 3), retransplantation (n = 16), and others (n = 20). Forty patients (12.5%) received blood type incompatible grafts. Thirty patients (9.3%) received right lobe with middle hepatic vein graft. A total of 121 patients (37.7%) received biliary reconstruction using Roux-en-Y and 192 (59.8%) had duct-to-duct anastomosis, while 8 (2.5%) patients underwent combined Roux-en-Y and duct-to-duct anastomosis. After the introduction of duct-to-duct anastomosis in July 1999, patients who had liver disease without extrahepatic biliary tract involvement were candidates for duct-to-duct anastomosis. The median follow-up period was 60 months (range, 7–80 months) in Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy and 34 months (range, 7–64 months) in duct-to-duct anastomosis (P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in patient characteristics between either group, except for the follow-up period and the patient age. Because of the patient population with biliary atresia in the Roux-en-Y group, the patient age was significantly younger in the Roux-en-Y group (P < 0.01) (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Patient Characteristics

Immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus and low-dose steroids.19 Patients who received blood type incompatible transplants had preoperative plasma exchange or double filtration plasmapheresis to reduce the anti-ABH antibody titer. Prostaglandin E1, cyclophosphamide, and additional steroids were administered from the portal vein or hepatic artery postoperatively.20,21

Statistical analysis was performed using the generalized Wilcoxon test. Actuarial survival rate was calculated with the nonparametric Kaplan-Meier method and was compared with the Wilcoxon test throughout the study. − values of less than 0.01 were considered significant.

The study was approved by the international review board and informed consent was obtained in all the cases.

Donor Operation

Standard right lobe technique was previously described.12,22,23 Before parenchymal transection, the right lobe was mobilized and the sizeable (>5 mm) right inferior hepatic vein was preserved with a caval cuff for reconstruction. After careful definition of biliary anatomy in the hepatic hilum using intraoperative cholangiography, the right hepatic duct was transected 2 to 3 mm away from the bifurcation. Minimal dissection of pericholedochal tissue was required at this point to maintain blood supply around the hepatic duct, and the hepatic duct was separated with fine scissors. Right-sided liver has a higher incidence of vascular and biliary variant. Overall, 39.6% of grafts had multiple bile ducts in our right lobe LDLT series, which poses a further difficulty in reconstruction.16,24 The right portal vein and the right hepatic artery were temporally clamped to clarify the parenchymal transection line. An 8-mm Penrose drain was passed between the right hepatic vein superiorly and the portal bifurcation inferiorly to maintain the cutting plane during parenchymal dissection. The end of remnant hepatic ducts were closed with a continuous suture using 6–0 polydioxanone absorbable monofilament, and cholangiogram was performed to ensure that there was no leakage or stricture.

Recipient Operation

Hilar dissection was carefully performed to preserve adequate blood supply of the epicholedodochal arterial plexus and the 2 distinct intramural arteries (3 and 9 o'clock arteries),25,26 and the bile duct was divided above the hilar bifurcation. Biliary anastomosis was performed with 6–0 polydioxanone absorbable monofilament suture after completion of vascular anastomosis. The graft hepatic duct was anastomosed to Roux-en-Y limb and/or bile duct. When bile ducts in a graft were far apart, they were anastomosed separately. In 8 grafts, the bile ducts were so far apart that both duct-to-duct and Roux-en-Y reconstructions were indicated. If the blood supply of the recipient cystic duct was sufficient and the recipient cystic duct was a better size match, the recipient cystic duct was used for the posterior duct reconstruction. Variations in technical preference remain, and modifications may be necessary to meet anatomic variants. The anastomosis was started at the posterior wall with interrupted or continuous suture, after which the anterior anastomosis was completed. A 4-French polyethylene tube was inserted for anastomotic decompression in some cases.

For internal stent in Roux-en-Y, 2 cm of 18G silicon vascular catheter was placed in the anastomosis. For external stent in Roux-en-Y, the 4-French tube was inserted through the jejunum and the tip was placed through the anastomosis. The stent tube was removed 8 weeks after transplantation.27

Biliary complications were diagnosed clinically and radiologically. Biliary leakage was defined by bilirubin level in the bilious ascites higher than the serum level, and stricture was diagnosed by dilated intrahepatic bile ducts with ultrasonography, hepatobiliary scan with Tc-99m Sn-N-pyridoxyl-5-methyltryptophan (99mTc-PMT), and radiologic intervention in all cases.28

RESULTS

Overall Incidence of Biliary Complication and Risk Factor

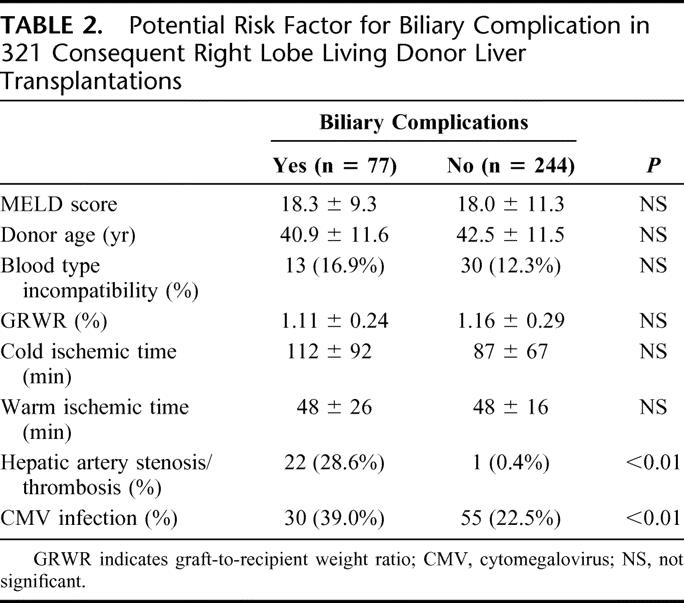

Of 321 right lobe LDLTs, 77 patients (24.0%) experienced 87 biliary complications (leakage: n = 27, 8.4%; stenosis: n = 60, 18.7%). There were no significant differences between the patient with or without biliary complication (n = 77 versus n = 244, respectively) in model for end-stage liver disease score (18.3 ± 9.3 versus 18.0 ± 11.3); donor age (40.9 ± 11.6 years versus 42.5 ± 11.5 years); percentage of blood type incompatibility (16.9% versus 12.3%); graft-to-recipient weight ratio (1.11 ± 0.24% versus 1.16 ± 0.29%); cold ischemic time (112 ± 92 minutes versus 87 ± 67 minutes); and warm ischemic time (48 ± 26 minutes versus 48 ± 16 minutes). However, the respective incidence of hepatic artery complications (28.6% versus 0.4%) and CMV infection (39.0% versus 22.5%) was significantly higher in the patients with biliary complications (P < 0.01) (Table 2). Blood type incompatibility was not a significant risk factor in overall right lobe LDLT series.

TABLE 2. Potential Risk Factor for Biliary Complication in 321 Consequent Right Lobe Living Donor Liver Transplantations

Overall incidence of biliary leakage and stricture were 12.4% and 8.3% in Roux-en-Y (n = 121), 4.7% and 26.6% in duct-to-duct (n = 192), and 0% in combined Roux-en-Y and duct-to-duct (n = 8), respectively. Duct-to-duct anastomosis showed significantly lower incidence of leakage and a higher incidence of stricture (P < 0.01). The onset of biliary leakage and stricture were 19.0 ± 7.7 days (range, 8–35 days; median, 17.5 days) and 12.3 ± 12.2 months (range, 2–36 months; median, 7.5 months) in Roux-en-Y, and 26.5 ± 26.1 day (range, 2–90 days; median, 20 days) and 8.7 ± 5.4 months (range, 2–35 months; median, 8 months) in duct-to-duct (P = not significant), respectively.

Analysis of Biliary Complication According to the Type of Anastomosis

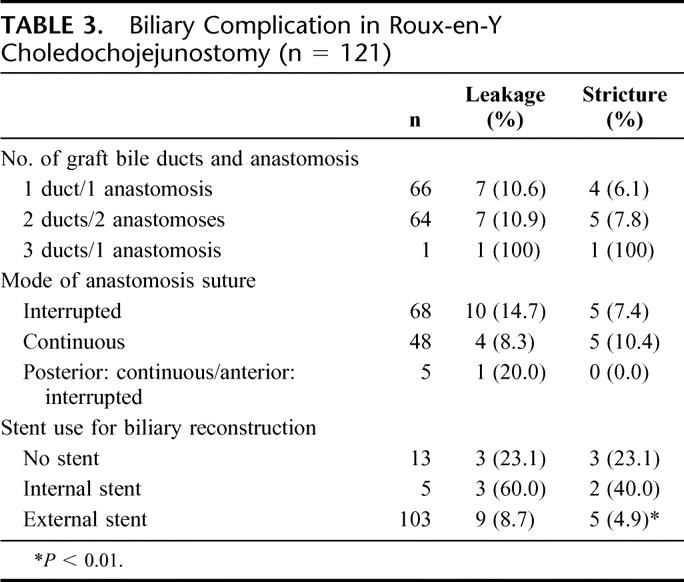

A total of 121 patients received Roux-en-Y biliary reconstruction (Table 3). There was no significant difference in biliary complications among the number of bile ducts in the graft and mode of anastomotic suture (P = not significant). There was a high incidence of biliary complications in the graft with 3 ducts. There was a trend toward a lower incidence of leakage and a higher incidence of stricture in continuous suture, but no significant difference was found among the groups. The patients with external stent (n = 103) showed lower incidence of biliary leakage compared with those with internal stent (n = 5), but this observation did not achieve statistical significance. The incidence of biliary stricture in the patients with external stent was significantly lower than in the patients without stent (n = 13) (P < 0.01).

TABLE 3. Biliary Complication in Roux-en-Y Choledochojejunostomy (n = 121)

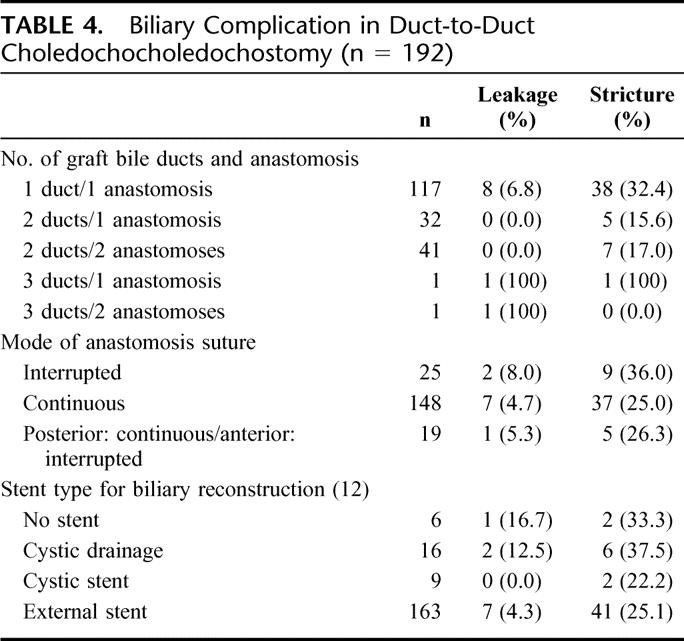

Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction was achieved in 192 cases (Table 4). If we focus on blood type incompatibility in biliary complication with duct-to-duct reconstruction, leakage and stricture was observed in 11.5% and 38.5% of the patients with blood type incompatibility; the incidence of biliary complications was significantly higher in duct-to-duct patients with blood+ type incompatibility (P < 0.01).

TABLE 4. Biliary Complication in Duct-to-Duct Choledochocholedochostomy (n = 192)

In 117 recipients (60.9%) of duct-to-duct anastomosis, the common bile duct was used to perform the reconstruction with a single right bile duct. In 11 of 117 patients with single duct-to-duct anastomosis (9.4%) and 8 of 41 patients with 2 anastomoses for 2 ducts (19.5%), a small incision (1–2 mm) in the anterior wall of the graft bile duct was made to accommodate the size mismatch. In 5 patients with one anastomosis for 2 ducts (15.6%), a ductoplasty was performed to enable a single anastomosis to the recipient common bile duct. In 6 of 41 patients with 2 anastomoses for 2 ducts (14.6%), the recipient cystic duct was used to perform the posterior duct reconstruction for better size matching. Two of them (33.3%) had biliary stricture at 2 and 6 months after transplantation. In another case with 2 ducts, the ducts were anastomosed to the recipient left and right hepatic ducts. Totally, there was no significant difference in biliary complications among the number of bile ducts in the graft and mode of anastomosis suture in duct-to-duct reconstruction. However, if the graft had 3 ducts, there was a high incidence of biliary complication.

In 188 cases, the biliary stent tube was inserted for anastomotic decompression in duct-to-duct anastomosis. For cystic drainage (n = 16), the stent was inserted through the remaining cystic duct and pushed downward into the recipient common bile duct. For cystic stent (n = 9), the tube was inserted through the remaining cystic duct and was placed through the anastomosis as a splint. For external stent (n = 163), the tube was placed through the anastomosis and was pulled out through the common bile duct.16 There was no significant difference in biliary complications according to the type of biliary stent in duct-to-duct reconstruction. If we compare the incidence of anastomotic complication in single duct-to-duct reconstruction (n = 117), the incidence of biliary leakage and stricture was 10.0% and 40% in interrupted suture, 7.2% and 31.3% in continuous suture, 0% and 28.6% in combined interrupted and continuous suture (P = not significant), respectively. Also, the use of the stent tube did not reduce biliary complications in single duct-to-duct anastomosis.

Clinical Outcome of Patients After Biliary Complication in Roux-en-Y Hepaticojejunostomy

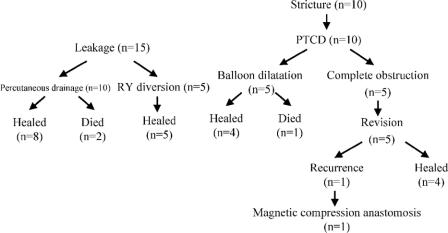

The clinical outcome of the patients with biliary complications in Roux-en-Y reconstruction is summarized in Figure 1. Two patients with bile leaks and one with biliary stricture died of sepsis. Biliary leakage was first treated with percutaneous drainage. When the amylase level of aspirated fluid was high or the patient's condition was critical, relaparotomy was indicated. Because the anastomosis appeared to be too fragile for revision, we put drains and carried out a Roux-en-Y enterostomy to isolate/rest the biliary anastomosis (Roux-en-Y diversion). Five patients received Roux-en-Y diversion. The enterostomy was removed after the leak had been successfully treated. Two patients died of septic complication after biliary leakage at 14 and 3 months after transplantation.

FIGURE 1. Summary of clinical outcome after biliary complications in Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy. PTCD, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and drainage.

Four of the 10 biliary strictures were secondary to biliary leakage. Anastomotic stricture was initially managed with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiodrainage (PTCD). Five patients were successfully treated with balloon dilatation. Five patients (50%) with complete anastomotic obstruction required surgical revision. One patient developed biliary stricture after surgical revision and was treated with magnetic compression anastomosis between the hepatic duct and Roux-en-Y loop, as proposed by Yamanouchi et al.29 One patient with biliary stricture died of sepsis after several courses of PTCD and balloon dilatation 11 months after transplantation. One patient who underwent revision surgery for biliary stricture died of recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma 30 months after transplantation.

Clinical Outcome of Patients After Biliary Complication in Duct-to-Duct Choledochocholedochostomy

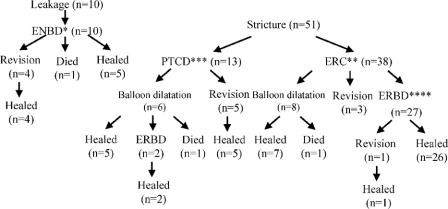

Figure 2 shows clinical outcome of the patients with biliary complications in duct-to-duct reconstruction. In patients with biliary leakage, endoscopic retrograde nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) was indicated as an initial treatment. Four of the 10 patients with biliary leakage required conversion to Roux-en-Y (n = 3) or reoperation with duct-to-duct reconstruction (n = 1). One patient with a blood type incompatible graft died of sepsis 11 months after transplantation. Five of 10 patients were successfully treated with ENBD.

FIGURE 2. Summary of clinical outcome after biliary complications in duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy. ENBD, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; ERC, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; PTCD, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and drainage; ERBD, endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage.

Six of the 51 biliary strictures (15.7%) were secondary to biliary leakage. Initially, anastomotic stricture was referred for endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC). Thirteen of 51 patients (25.5%) could not receive endoscopic treatment because of the difficulty in accessing the papilla of Vater and the difficulty of passing a guidewire through the tight anastomotic stricture. All of them required PTCD. Consequently, 5 patients underwent revision surgery with Roux-en-Y reconstruction to repair the stricture. Two patients with tight anastomotic stricture were closely observed for a week with PTCD for anastomotic decompression, and were successfully treated with endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD). Eight patients were treated with ERC balloon dilatation without placing inside stents. One patient died of sepsis secondary to chronic cholangitis 5 months after transplantation. The remaining 27 of 51 patients (52.9%) were treated by placing inside stents endoscopically above the sphincter of Oddi. One patient with a blood type incompatible graft underwent conversion to Roux-en-Y after ERBD because of acute cholangitis and hemobilia. As shown in Figure 2, 9 of 51 patients (17.6%) with duct-to-duct anastomotic stricture required surgical revision. The need for surgical revision due to biliary stricture tended to be lower in the duct-to-duct group compared with the Roux-en-Y group (50.0%), but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.03).

DISCUSSION

Right-lobe LDLT can provide an adequate graft size to compensate for the metabolic demands in most adult recipients, and the clinical outcome has improved in our series.22 Among the controversies in right lobe LDLT, techniques of biliary reconstruction remain an open question. Right-sided liver has a higher incidence of vascular and biliary variants, this was explained by the relative consistency between the left umbilical vein and the liver. Multiple biliary orifices are encountered in 26.0 to 39.6% of the cases, which presents a further difficulty in reconstruction in right lobe LDLT.16,24,30 For safe biliary reconstruction, precise evaluation of the biliary anatomy is essential.

The method for preoperative or intraoperative biliary duct evaluation remains a controversial topic for discussion. We have performed preoperative biliary duct evaluation with three-dimensional drip infusion cholangiographic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) cholangiography in the evaluation of the potential donor. Although it provides adequate anatomic information of the biliary system, adaptation of these valuable methods for potential donor candidates is not always possible because of the risk of allergic reaction to contrast medium and the cost. In our experience, intraoperative cholangiography is an adequate and convenient way to evaluate the donor biliary tree.

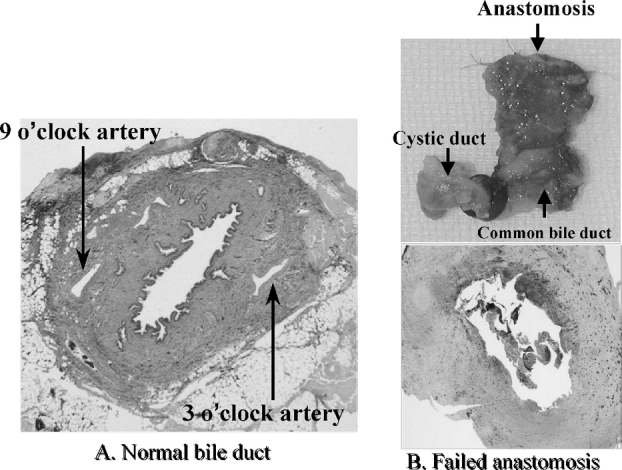

The blood supply for biliary anastomosis is a major concern in LDLT. The arterial blood supply of the biliary system has been described by several investigators. A previous study using fine casts showed that 60% of the arterial supply for the bile duct comes from the caudal side through periduodenal arteries, 38% from the cranial side and only 2% from the hepatic artery itself. The 3 o'clock, 9 o'clock, and retroportal arteries give rise to multiple arteriolar branches, which form a free anastomosis within the wall of the bile duct.26 In the absence of any attachments in transplanted liver recipients, the blood supply to the graft bile duct is derived solely from the hepatic artery. Histologic examination of disrupted duct-to-duct reconstruction often shows the loss of 3 o'clock and 9 o'clock intramural arteries on the recipient side (Fig. 3). Preservation of periductal microcirculation in the recipient duct and excellent hepatic artery reconstruction might be a key factor for successful duct-to-duct anastomosis.

FIGURE 3. Histologic examination of the failed duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy often shows the loss of the 3 and 9 o'clock arteries on the recipient side. Preservation of periductal microcirculation on the recipient side is a key factor for successful anastomosis. A, Normal common bile duct with patent 3 and 9 o'clock intramural arteries. B, Failed duct-to-duct choledochocholedochostomy with loss of 3 and 9 o'clock intramural arteries.

Our current study confirmed that arterial complications, CMV infection, and blood type incompatibility were significant and important etiologic variables in biliary complications.16,27 We do not use prophylactic administration of ganciclovir. However, the results of this study underline the importance of prophylaxis. In our LDLT program, a blood type incompatible graft was unavoidable in 12% of the recipients.21 Despite the application of preoperative plasma exchange, splenectomy, and enhanced immunosuppression, the 5-year survival rate in adult patients was less than 50% and nearly 70% of the adult patients had biliary complications. We started the intrahepatic arterial immunosuppression protocol from December 2001 and the preconditioning regimen with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody infusion from April 2004. Although it is still a tentative trial, these protocols have dramatically improved the outcome, with a 1-year graft survival rate of 85.7% and a biliary complication rate of 38.8%.31

There is still no consensus among transplant surgeons with regard to the type of biliary reconstruction in right lobe LDLT. Recently, the use of duct-to-duct reconstruction has been increasingly reported in LDLT.12,14,16,32 We have reported our initial experience of 51 cases of duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction and concluded that it represents a useful technique for right lobe LDLT.16 In July 1999, duct-to-duct reconstruction became the first choice for biliary reconstruction in our institution. In the series reported here, duct-to-duct technique had a lower incidence of biliary leakage. In cases of biliary leakage with duct-to-duct, peritoneal contamination from intestinal contents was minimized. In addition to the physiologic bilioenteric continuity and later good access by endoscopy, duct-to-duct reconstruction has an advantage over Roux-en-Y that the morbidity is reduced even when early anastomotic leakage occurs.

Biliary stricture was encountered in 26.6% of the patients with duct-to-duct reconstruction in this series, which was significantly higher than the Roux-en-Y group (4.7%). Although strictures seemed to develop more frequently in the duct-to-duct group, the requirement for surgical revision tended to be lower in that group. Because of easy access and imaging through endoscopy, 38 of 51 patients (74.5%) could be treated with ERC. Once ERBD was initiated, 26 of 27 patients (96.3%) were successfully treated. Recently, Gondolesi et al reported the largest Western experience with biliary complications in right lobe LDLT, and demonstrated that duct-to-duct reconstruction had higher incidence of stricture (31.7%) and lower incidence of leakage (16.3%), while the opposite was true following Roux-en-Y reconstruction (7.3% and 18.2%). Also, they recommended early and aggressive use of interventional treatment of biliary complications.32 We agree with this suggestion that early interventional treatment could avoid further operative intervention. Endoscopic biliary intervention is useful for most anastomotic strictures. Unless the anastomotic site is completely necrotic, insertion of a long-term short stent is very effective in securing bile drainage without increased risk of ascending cholangitis.17

Variations in technical preference remain and modifications may be necessary to take account of anatomic variants in biliary reconstruction. Biliary complications seemed to develop more frequently in graft with multiple bile duct; however, this did not reach statistical significance in the present series. Duct-to-duct reconstruction is safely applied even in multiple bile duct reconstruction with plasty of the graft bile duct or with combined duct-to-duct and Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Contrary to an old concept, duct-to-duct reconstruction has been successfully performed even with the recipient cystic duct,33 although the incidence of stricture in the cystic duct anastomosis was revealed to be high in our series (33.3%), and not just in a few left lobe grafts.34

With regard to biliary morbidity according to the reconstruction method used, we did not find any conclusive tendency to favor any mode or suture. The use of synthetic monofilament suture material was reported to be feasible for biliary reconstruction because of reduced tissue reaction by synthetic materials, as well as bacterial adherence.35 The Paul Brousse group recommended nonabsorbable suture rather than absorbable material because the resorption of the latter might induce local inflammation and subsequent stenosis.36 Trends remain in the Roux-en-Y group toward lower incidence of stricture in interrupted suture and lower incidence of leakage in continuous suture in the present study. Our current preference is the use of 6–0 or 7–0 nonabsorbable running suture at the posterior wall and interrupted suture at the anterior wall.

Stenting of the anastomosis is another topic for discussion in LDLT. The rationale of stent is the maintenance of biliary flow despite swelling of anastomosis and easy access for control cholangiography in case of suspected leakage or stricture.37 The external stent tends to reduce biliary complication in the Roux-en-Y reconstruction, which was consistent with our previous series of 400 pediatric LDLTs.27 Although our preliminary right lobe with duct-to-duct series demonstrated that the external stent significantly reduced the incidence of biliary stricture,12,16 overall incidence of biliary stricture was considerably high (26.6%) in long-term follow-up. Scatton et al reported that employment of a T tube increased incidence of biliary complications and recommended the performance of duct-to-duct without a T tube in deceased liver transplantation.38 The most frequent complication was leakage after T tube removal. We do not experience leakage after removal of 4-Fr biliary tube in the present series. To confirm this finding, while we formerly used a small stent tube, we ceased to use it from July 2004 and are monitoring the results.

CONCLUSION

Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in right lobe LDLT appears to be a feasible option with better endoscopic access for treating biliary stricture. Long-term observation may be necessary to collect sufficient data for the establishment of this treatment modality. It is hoped that increased experience and continuing refinements of the technique will lead to improved outcomes in right lobe LDLT.

Footnotes

Supported in part by grants from the Scientific Research Fund of the Ministry of Education and by a Research Grant for Immunology, Allergy and Organ Transplant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

Reprints: Mureo Kasahara, MD, Department of Transplant Surgery, Kyoto University Hospital, 54 Kawara-cho, Shogoin, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. E-mail: mureo@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sutcliffe R, Maguire D, Mroz A, et al. Bile duct stricture after adult liver transplantation: a role for biliary reconstructive surgery? Liver Transplantation. 2004;10:928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lerut J, Gordon RD, Iwatsuki S, et al. Biliary tract complications in human orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1987;43:47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stratta RJ, Wood RP, Langnas AN, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Surgery. 1989;106:675–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chardot C, Candinas D, Miza D, et al. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: Birmingham's experience. Transplant Int. 1995;8:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tung BY, Kimmery MB. Biliary complications of orthotopic liver transplantation. Dig Dis. 1999;17:133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colonna JO, Shaked A, Gomes AS, et al. Biliary strictures complicating liver transplantation: incidence, pathogenesis, management and outcome. Ann Surg. 1992;216:344–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Urdazpal L, Balls KP, Gores GJ, et al. Increased bile duct complications in liver transplantation across the ABO barrier. Ann Surg. 1993;218:152–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbasogla O, Levy MF, Vodapally MS, et al. Hepatic artery stenosis after liver transplantation: incidence, presentation, treatment and long-term outcome. Transplantation. 1997;63:250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halme L, Hockerstedt K, Lautenschlager I. Cytomegalovirus infection and development of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:1853–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trotter JF, Wachs M, Everson GT, et al. Adult-to-adult transplantation of the right hepatic lobe from a living donor. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1074–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian YB, Liu CL, Lo CM, et al. Risk factors for biliary reconstructions after liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1101–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura T, Tanaka K, Kiuchi T, et al. Anatomical variations and surgical strategies in right lobe living donor liver transplantation: lessons from 120 cases. Transplantation. 2002;73:1896–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcos A, Fisher RA, Ham JM, et al. Right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68:798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dulundu E, Sugawara Y, Sano K, et al. Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in adult living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:574–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grewal HP, Shokouh-Amiri MH, Vera S, et al. Surgical technique for right lobe adult living donor liver transplantation without venovenous bypass or portocaval shunting and with duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction. Ann Surg. 2001;233:502–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishiko T, Egawa H, Kasahara M, et al. Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in living donor liver transplantation utilizing right lobe graft. Ann Surg. 2002;236:235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hisatsune H, Yazumi S, Egawa H, et al. Endoscopic management of biliary strictures after duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in right-lobe living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;76:810–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31:864–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inomata Y, Tanaka K, Egawa H, et al. The evolution of immunosuppression with FK506 in pediatric living related liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanabe M, Shimazu M, Wakabayashi G, et al. Intraportal infusion therapy as a novel approach to adult ABO-incompatible liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73:1959–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egawa H, Oike F, Buhler L, et al. Impact of recipient age on outcome of ABO-incompatible living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;77:403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inomata Y, Uemoto S, Asonuma K, et al. Right lobe graft in living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69:258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inomata Y, Egawa H. Surgical procedure for right lobectomy. In: Tanaka K, Inomata Y, eds.. Living-Donor Liver Transplantation. Barcelona: Prous Science, 2003:43–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasahara M, Egawa H, Ogawa K, et al. Variations in biliary anatomy associated with trifurcated portal vein in right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;79:626–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stapleton GN, Hickman R, Terblanche J. Blood supply of the right and left hepatic ducts. Br J Surg. 1998;85:202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Northover JM, Terblanche J. A new look at the arterial supply of the bile duct in man and its surgical implications. Br J Surg. 1979;66:379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egawa H, Inomata Y, Uemoto S, et al. Biliary anastomotic complications in 400 living related liver transplantation. World J Surg. 2001;25:1300–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanazawa A, Kubo S, Tanaka H, et al. Bile leakage after living donor liver transplantation demonstrated with hepatobiliary scan using 99mTc-PMT. Ann Nucl Med. 2003;17:507–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takao S, Matsuo Y, Shinchi H, et al. Magnetic compression anastomosis for benign obstruction of common bile duct. Endoscopy. 2001;33:988–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohkubo M, Nagino M, Kajima J, et al. Surgical anatomy of the bile ducts at the hepatic hilum as applied to living donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2004;239:82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oike F, Egawa H, Kozaki K, et al. Dramatic improvement in the outcome of ABO-incompatible liver transplantation from living donor by hepatic arterial infusion therapy. Am J Transplant. 2004;8(suppl):293. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gondolesi GE, Varotti G, Florman SS, et al. Biliary complications in 96 consecutive right lobe living donor transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2004;77:1842–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suh KS, Choi SH, Yi NJ, et al. Biliary reconstruction using the cystic duct in right lobe living donor liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:661–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soejima Y, Shimada M, Suehiro T, et al. Feasibility of duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in left-lobe adult-living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:557–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson BJ, Marsh JW, Makowka L, et al. Biliary tract complications in orthotopic adult liver transplantation. Am J Surg. 1989;158:68–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azoulay D, Hargreaves GM, Castaing D, et al. Duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis in living related liver transplantation: the Paul Brousse Technique. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1197–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Settmacher U, Steinmuller TH, Schmidt SC, et al. Technique of bile duct reconstruction and management of biliary complications in right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scatton O, Meunier B, Cherqui D, et al. Randomized trial of choledochocholedochostomy with or without a T tube in orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2001;233:432–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]