Abstract

Produce isolates of the Escherichia coli Ont:H52 serotype carried Shiga toxin 1 and stable toxin genes but only expressed Stx1. These strains had pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles that were 90% homologous to clinical Ont:H52 strains that had identical phenotypes and genotypes. All Ont:H52 strains had identical single nucleotide polymorphism profiles that are suggestive of a unique clonal group.

Fresh produce have been implicated in outbreaks of Salmonella, Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) (15). The Monitoring Programs Office of the USDA Agriculture Marketing Service, Science and Technology, initiated the Microbiological Data Program (MDP) to survey produce for the presence of pathogens, including STEC and ETEC. Using a multiplex PCR assay (S. Monday and P. Feng, unpublished data), two E. coli strains, MDP 04-02111 and MDP 04-01392, isolated from cilantro and cantaloupe, respectively, were found to carry both Shiga toxin (Stx) and stable toxin (ST) genes. Since pathogenic E. coli are classified based on trait virulence factors, it was unexpected that these strains had both STEC and ETEC virulence genes. In this study, these strains were characterized by phenotypic, serologic, and genetic assays as well as by molecular subtyping to determine their genetic relatedness to other pathogenic E. coli strains.

The MDP strains were streak plated onto various selective and differential media and confirmed to be pure cultures. These strains had typical E. coli phenotypes, including sorbitol fermentation, β-galactosidase, and β-glucuronidase activities and were biochemically identified as E. coli strains (Vitek GNI Plus; bioMerieux, Hazelwood, MO).

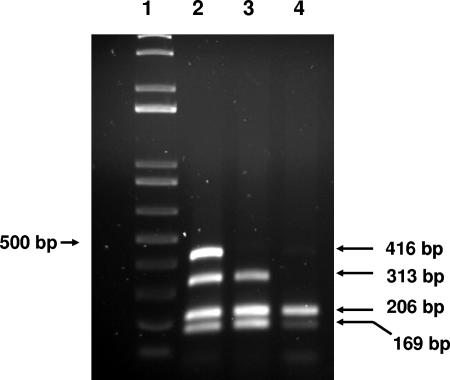

To verify that MDP strains carried both ST and Stx genes, they were retested by ETEC/STEC multiplex PCR. The assay used primers (Table 1) specific for the ETEC heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) and ST genes, including both the ST and STIa alleles; one primer pair that detected both stx1 and stx2 of STEC; and primers to the 16S rRNA gene, which served as an internal amplification control. The 50-μl reaction mix contained 1× Taq polymerase buffer (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), 3 mM MgCl2, 400 μM of deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 150 nM of each primer, except for the ST primers (200 nM), 100 to 250 ng of DNA template, and 2.5 U of HotStarTaq (QIAGEN). The “touchdown” PCR (2) conditions were as follows: 95°C for 15 min and then 10 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 69° to 60°C (−1°C/cycle) for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s and a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products (Fig. 1) showed that the positive control (lane 2), consisting of mixed DNA from strains 35150 and 35401 (Table 2), yielded all four expected products, and MDP strains 04-02111 (lane 3) and 04-01392 (not shown) were confirmed to produce both the Stx- and ST-specific products of 313 bp and 169 bp, respectively. Since the stx-specific 3′ primer used in the multiplex assay is specific to a homologous region of stx1 and stx2 and will detect both genes, we used 5P PCR (6) and determined that the MDP strains carried only stx1 but no other STEC genes such as stx2, ehxA (enterohemolysin), the +93 single nucleotide polymorphism in uidA (β-glucuronidase) that is unique to O157:H7 (5), or γ-eae (intimin) that is found mostly in O157:H7 and closely related serotypes (14) (data not shown). PCR analysis for other eae variants showed that the MDP strains also did not carry any other intimin alleles commonly present in STEC (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

ETEC/STEC multiplex PCR primers used to amplify specific fragments from the LT, ST, Stx1, Stx2, and 16S rRNA genes

| Target | Size (bp) | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA gene | 206 | VMP5 | AAG AAG CAC CGG CTA ACT CC |

| VMP6 | CGC ATT TCA CCG CTA CAC C | ||

| ST gene | 169 | SRM148a | TCT GTA TTA TCT TTC CCC TCT TTT AGT C |

| SRM148Ba | GTA TTG TCT TTT TCA CCT TTC GCT C | ||

| SRM149 | GCA GGA TTA CAA CAC ART TCA CAG C | ||

| LT gene | 416 | SRM152 | CGA CAG ATT ATA CCG TGC TGA CTC |

| SRM154 | GTA ATC GTT CAT CAA TCA CAC CAA | ||

| stx1/stx2 | 313 | 5′ Stx1.1b | CTG GAT TTA ATG TCG CAT AGT GG |

| 5′ Stx2.1b | CTG GCG TTA ATG GAG TTC AGT G | ||

| SRM129 | TGA TGA TGA CAA TTC AGT ATA ACT GCC AC |

Mix of these primers to enable detection of STI and STIa.

Mix of these primers to enable detection of Stx1 and Stx2.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA fragments amplified by the ETEC/STEC multiplex PCR. Lanes: 1, 1-kb Plus DNA ladder (Invitrogen, Calrsbad, CA); 2, mixed DNA from strains 35150 and 35401; 3, MDP 04-02111; 4, FDA119. The products shown in lane 2 (from top to bottom) and their sizes are as follows: LT, 416 bp; stx, 313 bp; 16S rRNA gene, 206 bp; ST, 169 bp.

TABLE 2.

E. coli strains examined in this studya

| Strain | Serotype | Group | Virulence factor(s) | Sourceb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35150 | O157:H7 | EHEC | Stx1, Stx2 | ATCC |

| 35401 | O78:H11 | ETEC | LT, ST | ATCC |

| 38 | NAc | Wild type | NA | FDA |

| 04-02111 | Ont:H52 | STEC/ETEC | ST, Stx1 | MDP |

| 04-01392 | Ont:H52 | STEC/ETEC | ST, Stx1 | MDP |

| 103 | NA | ETEC | ST, LT | FDA |

| 119 | NA | ETEC | ST | FDA |

| 13C07 | O26:H11 | STEC | Stx1 | FDA |

| TW01387 | O111:H8 | STEC | Stx1 | STEC Center |

| TW05622 | O138 | STEC/ETEC | ST, Stx2 | STEC Center |

| TW07509 | Ond:H52d | STEC/ETEC | ST, Stx1 | STEC Center |

| TW10123 | Ont:H52d | STEC/ETEC | ST, Stx1 | STEC Center |

The serotype and virulence factor information was previously published or determined in this study.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA.

NA, not applicable or information not available.

Ond or Ont, O antigen not determined or nontypable.

Although genetic evidence showed the presence of both the ST and Stx1 genes in MDP strains, it was uncertain whether the genes were actually expressed. Serological testing with VTEC-RPLA (Denka Seiken, Japan) confirmed that both strains had Stx1 titers of 1:128 (see Table 3), but analysis with the E. coli ST EIA (Oxoid, England) showed the absence of ST production (see Table 3). These results indicate that the MDP strains carry the ST gene but do not appear to produce ST under laboratory conditions. Both MDP strains had an untypeable O antigen and are of the Ont:H52 serotype (Gastroenteric Disease Center, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA).

TABLE 3.

Results of serological toxin analysis of various E. coli strains

| Strain | Source | Stx1 titer | ST OD490a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | FDA | NAb | 0.72 |

| 35150c | ATCC | 1:512 | NA |

| 119d | FDA | NA | 0.05 |

| MDP 04-02111 | Michigan | 1:128 | 0.69 |

| MDP 04-01392 | Maryland | 1:128 | 0.82 |

| TW07509 | Virginia | 1:256 | 0.54 |

| TW10123 | Michigan | 1:128 | 0.69 |

Competitive immunoassay; values above 0.5 indicate negative ST production. OD490, optical density at 490 nm.

NA, not applicable.

STEC O157:H7 strain used as positive control for Shiga toxin production.

ETEC strain used as positive control for ST production.

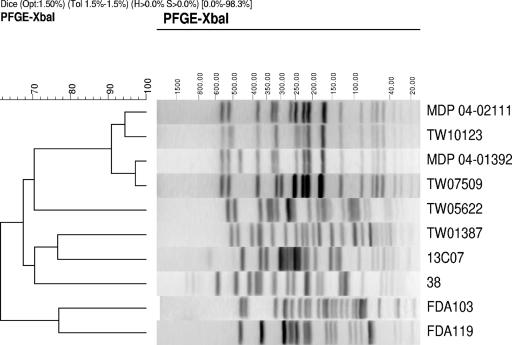

These MDP strains have identical traits but were isolated from different produce from different localities (see Table 3). Hence, to determine if they are identical or closely related strains, XbaI digests of both strains were examined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (1) and compared to those of other STEC, ETEC, and E. coli strains. The two MDP strains had near-identical PFGE profiles that were very distinct from those of E. coli and other Stx1- or ST-producing E. coli strains (Fig. 2). However, their XbaI profiles had >90% homology to two clinical Ont:H52 strains (TW10123 and TW07509) that had phenotypes and genotypes identical to those of the MDP strains (Tables 2 and 3). Strain TW07509, obtained from the CDC, was isolated in 1998 from an 11-month-old patient with diarrhea in Virginia who was also infected with rotavirus, while MDP 04-01392 was isolated in 2004 from cantaloupe sampled in Maryland. Despite the proximity of the two isolation locations, there were no clear associations between these strains. On the other hand, MDP 04-02111, isolated in 2004 from cilantro sampled in Michigan, had >95% homology to TW10123, which was also isolated in Michigan 2 years earlier from a patient with bloody diarrhea who was thought to have acquired the infection from a Mexican-style restaurant. Since cilantro is an often-used ingredient in these types of restaurants, it seems beyond coincidence and possible that this strain may have been the causative agent of illness.

FIG. 2.

PFGE profiles of XbaI-digested genomic DNA and the dendrogram comparing profile similarities. The cluster tree was constructed using BioNumerics (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) from comparisons of XbaI-digested PFGE patterns of the strains listed in Table 2. Opt, optimization; Tol, tolerance; H, height; S, surface.

The intended use of the ETEC/STEC PCR was to detect ETEC and STEC in produce; hence, the inadvertent isolation of the Ont:H52 strains that carried both ETEC and STEC virulence genes was unexpected. Many of the virulence genes in E. coli reside on mobile genetic elements. The LT and ST genes of ETEC are encoded by plasmids, which can be transferred by conjugation (18). Likewise, the stx genes are encoded by bacteriophages, which can be spontaneously induced during subculture (4, 8) and may, theoretically, infect other bacteria. Strains of Shiga toxin-producing Citrobacter freundii and Enterobacter cloacae have been isolated (12, 16), leading to speculations that enteric bacteria may be acquiring stx genes in environments such as sewage, which contains high titers of stx-bearing phages (11). We speculated that the Ont:H52 strains may be an ETEC strain that was infected by the Stx1 phage or, conversely, an STEC strain that acquired the ST-encoding plasmid, but their XbaI profiles resembled neither those of Stx1-producing STEC strains nor those of the ST-producing ETEC strains examined (Fig. 2).

Strains that share H-antigen types are often related and genetically clustered. Previously, in Japan, O74:H52 and O165:H52 strains were isolated from cattle (10) and humans (7), respectively, and like the Ont:H52 strains, they only produced Stx1. Although we did not examine these Japanese strains, we did examine strains of the O157:H52, O142:H52, and O4:H52 serotypes by PFGE, and their profiles were very distinct from those of Ont:H52 strains (data not shown). These findings suggest that the Ont:H52 strains may belong to a distinct lineage. This assumption was supported by multilocus sequence typing (9) of seven housekeeping genes, which confirmed that all Ont:H52 strains had identical single nucleotide polymorphism profiles, which placed them in sequence type 274. The sequence type 274 profile had not been seen previously in the pathogenic E. coli multilocus sequence typing database (13), and it does not fall into any of the defined clonal groups (3, 17); hence, it appears to be a unique STEC clone.

In conclusion, the Ont:H52 strains isolated from both produce and clinical sources had identical traits and carried the STEC stx1 and ETEC ST genes, but only Stx1 was expressed. The Ont:H52 strains shared similar PFGE profiles and an identical but distinctive sequence type, indicating that they are a unique STEC clonal group. However, the evidence implicating this STEC serotype in illness remains circumstantial at present.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1998. Standardized molecular subtyping of food borne bacterial pathogens by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: CDC training manual. Food Borne and Diarrheal Diseases Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

- 2.Don, R. H., P. T. Cox, B. J. Wainwright, K. Baker, and J. S. Mattick. 1991. “Touchdown” PCR to circumvent spurious priming during gene amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnenberg, M. S., and T. S. Whittam. 2001. Pathogenesis and evolution of virulence in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Investig. 107:539-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng, P., M. Dey, A. Abe, and T. Takeda. 2001. Isogenic strain of Escherichia coli O157:H7 that has lost both Shiga toxin 1 and 2 genes. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:711-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng, P., K. A. Lampel, H. Karch, and T. S. Whittam. 1998. Sequential genotypic and phenotypic changes in the emergence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1750-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng, P., and S. R. Monday. 2000. Multiplex PCR for detection of trait and virulence factors in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serotypes. Mol. Cell. Probes 14:333-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukushima, H., K. Hoshina, and M. Gomyoda. 2000. Selective isolation of eae-positive strains of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1684-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karch, H., T. Meyer, H. Russmann, and J. Heesemann. 1992. Frequent loss of Shiga-like toxin genes in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli upon subcultivation. Infect. Immun. 60:3464-3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Large, T. M., S. T. Walk, and T. S. Whittam. 2005. Variation in acid resistance among Shiga toxin-producing clones of pathogenic Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2493-2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyao, Y., T. Kataoka, T. Nomoto, A. Kai, T. Itoh, and K. Itoh. 1998. Prevalence of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli harbored in the intestine of cattle in Japan. Vet. Microbiol. 61:137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muniesa, M., and J. Jofre. 1998. Abundance in sewage of bacteriophages that infect Escherichia coli O157:H7 and that carry the Shiga toxin 2 gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2443-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paton, A. W., and J. C. Paton. 1996. Enterobacter cloacae producing a Shiga-like toxin II-related cytotoxin associated with a case of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:463-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi, W., D. W. Lacher, A. C. Bumbaugh, K. E. Hyma, L. M. Ouellette, T. M. Large, C. L. Tarr, and T. S. Whittam. 2004. EcMLST: an online database for multi locus sequence typing of pathogenic Escherichia coli, p. 520-521. Proceedings of the IEEE 2004 Computational Systems Bioinformatics Conference. IEEE Computer Society Press, Los Alamitos, Calif.

- 14.Reid, S. D., D. J. Betting, and T. S. Whittam. 1999. Molecular identification of intimin alleles in pathogenic Escherichia coli by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2719-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivapalasingam, S., C. R. Friedman, L. Cohen, and R. V. Tauxe. 2004. Fresh produce: a growing cause of outbreaks of food borne illness in the United States, 1973 through 1997. J. Food Prot. 67:2342-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tschape, H., R. Prager, W. Streckel, A. Fruth, E. Tietze, and G. Bohme. 1995. Verocytotoxigenic Citrobacter freundii associated with severe gastroenteritis and cases of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in a nursery school: green butter as the infection source. Epidemiol. Infect. 114:441-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittam, T. S. 1998. Evolution of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains, p. 195-209. In J. B. Kaper and A. D. O'Brien (ed.), Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Wolf, M. K. 1997. Occurrence, distribution, and associations of O and H serogroups, colonization factor antigens, and toxins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:569-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]