Abstract

Burkholderia xenovorans strain LB400, which possesses the biphenyl pathway, was engineered to contain the oxygenolytic ortho dehalogenation (ohb) operon, allowing it to grow on 2-chlorobenzoate and to completely mineralize 2-chlorobiphenyl. A two-stage anaerobic/aerobic biotreatment process for Aroclor 1242-contaminated sediment was simulated, and the degradation activities and genetic stabilities of LB400(ohb) and the previously constructed strain RHA1(fcb), capable of growth on 4-chlorobenzoate, were monitored during the aerobic phase. The population dynamics of both strains were also followed by selective plating and real-time PCR, with comparable results; populations of both recombinants increased in the contaminated sediment. Inoculation at different cell densities (104 or 106 cells g−1 sediment) did not affect the extent of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) biodegradation. After 30 days, PCB removal rates for high and low inoculation densities were 57% and 54%, respectively, during the aerobic phase.

Approximately 635 million kg of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were produced in the United States from 1929 to 1978, and a similar amount was manufactured in Japan, Europe, and the former USSR (19). Of the total amount, it is estimated that 31% has been released into the environment, contaminating soils and sediments (16). The high hydrophobicities of PCB molecules contribute to their accumulation in higher-trophic-level species and their long-term environmental persistence.

Over the past 30 years, research on PCBs has shown that these compounds, previously thought to be recalcitrant, can be degraded by both anaerobic and aerobic bacteria. Under anaerobic conditions, anaerobic microbial consortia convert highly chlorinated congeners into less chlorinated biphenyls by reductive dechlorination, leaving the rings intact (3, 7, 30, 31). Under aerobic conditions, some microorganisms with more versatile oxidative capabilities can cleave lesser chlorinated biphenyl rings to yield chlorinated benzoates and pentanoic acid derivatives (28), which are often degradable by other bacteria. Hence, a sequential anaerobic/aerobic microbial process has the potential for the complete biodegradation of PCBs (25). Such a sequence could enable natural attenuation at aerobic-anaerobic interfaces (9) as well as be developed into a PCB bioremediation technology (37, 39).

Because of their abilities to attack a wide range of PCB congeners, Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 and Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 are two of the more promising strains for use in the aerobic stage of a PCB biotreatment process. However, as is true of other PCB-degrading microorganisms, at best they have limited ability to grow on PCBs (29), so repeated additions (bioaugmentation) would be required for biotreatment. Both strains accumulate chlorobenzoates during PCB degradation. We reasoned that by adding genes for the dechlorination of chlorobenzoates, we could enable these strains to grow on PCBs well enough to avoid the need for repeated bioaugmentation. We have previously demonstrated this approach by separately transferring ortho (ohb) and para (fcb) chlorobenzoate-dechlorinating genes to Comamonas testosteroni VP44, obtaining constructs capable of growth on 4-chlorobenzoate (4-CBA) and 4-chlorobiphenyl (4-CB) or 2-CBA and 2-CB (17). Similarly, we transferred fcb genes to RHA1, enabling it to grow on 4-CBA and 4-CB (33).

While there have been many experiments testing the ability of various aerobic bacteria to degrade PCBs, most of the work employed only one congener (27), employed a freshly applied contaminant (21), and/or was carried out under resting cell conditions (1, 26). While providing useful information, these types of experiments do not reflect the conditions under which aerobic bacteria have to perform in a biotreatment process for PCBs. PCB-contaminated sites contain a full spectrum of congeners coming from Aroclor spills, and the lengthy time they have usually had to partition into soil or sediment organic matter makes them less bioavailable than freshly spiked PCBs. Furthermore, PCB-degrading bacterial strains added to PCB-contaminated soil or sediment have to compete effectively with the indigenous soil microorganisms. These factors need to be taken into account in assessing the suitability of aerobic PCB-degrading microorganisms for use in a biotreatment process.

The work reported here is an extension of our approach of adding chlorobenzoate-degrading capabilities to competent PCB-degrading microorganisms, coupled with an evaluation of the constructs obtained for use in the aerobic stage of a sequential anaerobic/aerobic biotreatment process for PCBs. We introduced ohb genes into LB400 and tested the construct first for its ability to grow on 2-chlorobenzoate and then for its ability to degrade and grow on selected PCB congeners typically formed from the microbial dechlorination of Aroclors. Finally, we simulated a sequential anaerobic/aerobic biotreatment process by dechlorinating Aroclor 1242 in anaerobic sediment slurries, establishing aerobic conditions, and adding LB400(ohb) and RHA1(fcb) together to the sediments. The constructs remained genetically stable and degraded 57% of the remaining PCBs while growing in number, successfully competing with indigenous bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The strains used in this study were Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 (24), Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 (6), and Escherichia coli JM109 (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). Recombinant cells were grown on synthetic K1 medium (41) containing 2 mM 2- or 4-CBA or 3 mM biphenyl (nominal concentration), and, when required, 10 μg/ml of tetracycline was added. Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing rifampin (50 μg/ml) were used for reisolating cells from 10-fold dilutions of sediments (33).

Construction of recombinant strains.

A gram-positive/gram-negative shuttle vector, pRT1, was developed previously and used to transform Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 with the fcbABC operon, allowing it to grow on 4-CBA (33). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa 142 ohbABCR genes (3.7-kb XbaI-KpnI fragment) (38) were subcloned from plasmid pE43 into plasmid pRT1, yielding the plasmid pRO41 (Table 1). This clone confers the ability to grow on 2-CBA. Restriction and DNA-modifying enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.) and used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids, bacterial strains, probes, and primers used in this study

| Plasmid, strain, or primer | Characteristics or sequence (5′-3′) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pRT1 | Gram-positive/gram-negative shuttle vector containing the RC1 replicon | 33 |

| pRHD34 | Same as pRT1, but containing the fcbABC genes | 33 |

| pE43 | pOD33 derivative containing the ohb genes | 38 |

| pRO41 | Same as pRT1, but containing the ohb genes from pE43 | This work |

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli JM109 | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 λ− Δ(lac-proAB) [F′ traD36 proAB laclqZΔM15] | Promega Corp. |

| Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1(fcb) | Recombinant 4-chlorobenzoate degrader, Rifr | 33 |

| Burkholderia xenovorans LB400(ohb) | Recombinant 2-chlorobenzoate degrader, Rifr | This work |

| Primers and probesa | ||

| Forward fcb (2,159-2,175) | GTT GAT CGC CGC CAA TG | 32 |

| TaqMan fcb (2,139-2,157) | FAM-CGG CTT CTC GAT CCG CGC C-TAMRA | 32 |

| Reverse fcb (2,115-2,135) | TGG TAC GGC ACT AGG TGT A | 32 |

| Forward ohb (3,054-3,051) | CGA CCG CAT CGT CTC CTT | This work |

| Taqman ohb (3,056-3,081) | FAM-CAC GCC AAC ATC TAC TCC CAA CAC GC-TAMRA | This work |

| Reverse ohb (3,101-3,118) | GGC TTT CAC GCG CAC ATT | This work |

| F599fcbB (2,068-2,090) | GGT CCA GCG CGA AAT CCA GTC | 33 |

| R599fcbB (2,647-2,666) | CCC CCG CAC ACC GCA TCA AG | 33 |

| F580ohb (3,321-3,344) | GCG GAC AAG CGT TTC GAT ACA GGA | This work |

| R580ohb (3,877-3,899) | GCT TGC AGT TGC GCT TGA TGA T | This work |

The plasmid pRO41 was purified from E. coli cells with a Wizard miniprep kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) and transformed into LB400 by electroporation (33). Transformed cells were selected on LB containing tetracycline (10 μg/ml) and replica plated on K1 medium amended with biphenyl or 2-CBA as the carbon source.

Growth assay on 2-CBA.

Transformants were inoculated into K1 synthetic medium containing 3 mM 2-CBA. Cultures were incubated in duplicate at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 150 rpm. Growth was measured as the increase in optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Chloride release was analyzed colorimetrically (4). Substrate disappearance was monitored by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (23).

Growth assay on synthetic PCB mixtures M and C.

Stock acetone solutions of mixes M and C contained the eight more abundant PCB congeners present in patterns M and C, respectively, in the approximate proportions observed in laboratory experiments generating pattern M and C profiles from Aroclor 1242 (42). The concentrations of congeners in mix M (μmoles/ml acetone) were as follows: 2-CB, 8.0; 4-CB, 2.1; 2,4-CB, 1.4; 2,6-CB, 3.6; 2,2′-CB, 10.8; 2,4′-CB, 12.3; 2,2′,4-CB, 6.4; and 2,4,4′-CB, 5.4. The concentrations in mix C were as follows: 2-CB, 25.0; 4-CB, 2.5; 2,4-CB, 0.5; 2,6-CB, 5.0; 2,2′-CB, 15.0; 2,4′-CB, 1.0; 2,2′,4-CB, 0.5; and 2,4,4′-CB, 0.5.

LB400(ohb) cells were grown in K1 liquid medium with repeated additions of 2 mM 2-CBA up to an OD600 of 1.0. Substrate exhaustion was verified by HPLC. The total amount of substrate used was 5 mM. The CBA-grown cells were then inoculated into K1 liquid medium with biphenyl as the only carbon source. The control strain LB400 was also grown on biphenyl. To measure growth on PCBs, 1 ml of stock mix M or C solution was added to each tube, and the acetone was allowed to evaporate. Ten milliliters of K1 medium was then added, and the tube was inoculated. The total PCB concentration was nominally 5 mM. Growth was assessed by measuring the optical density of the cultures at 600 nm at 24-h intervals. PCB disappearance was monitored by gas chromatography (23).

Analysis of CBAs and HOPDAs.

Chlorobenzoic acids were analyzed by HPLC, using a Hewlett-Packard 1050 chromatograph equipped with a reverse-phase RP-18 column (Alltech) with 4.6 mm of internal diameter and 250 mm of length. The aqueous solvent contained 1 ml of 85% ortho-phosphoric acid and 600 ml of methanol per liter. The flow rate was 1.5 ml/min. The HPLC detector was set at 230 nm. Products were identified by comparison of retention times with those of authentic standards. The formation of 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dienoic acids (HOPDAs) was analyzed by visible spectral scanning of the cell-free supernatant (23).

Generation of Aroclor 1242 dechlorination products.

Sediment (91.1% sand, 8.1% silt and clay, 6.7% organic matter, 0.71% total nitrogen, pH 7.2) was collected from the Red Cedar River (MI), air dried, and passed through a 4-mm-mesh sieve. Slurries of the sediment in a reduced anaerobic mineral medium (34) were spiked to a concentration of 70 μg PCBs per gram sediment dry weight with Aroclor 1242 in a small volume of acetone. River Raisin (MI) sediments were placed in Erlenmeyer flasks previously flushed with an oxygen-free nitrogen and carbon dioxide (80:20) gas mixture. An equal volume of sterile reduced anaerobic mineral medium was added to the sediments, and the contents were shaken for 2 min and allowed to settle (31). The supernatant, containing eluted PCB-dechlorinating microorganisms, was used to inoculate the Red Cedar River contaminated sediment. Sealed flasks were incubated anaerobically in the dark at room temperature for 1 year. The sediments, containing a mixture of Aroclor 1242 dechlorination products, were then air dried and used in aerobic PCB degradation assays.

Aerobic sediment microcosms.

Natural rifampin-resistant variants (35) of the recombinants RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb) were grown on 3 mM (nominal concentration) biphenyl-containing medium. Cells were washed once with K1 medium, resuspended, and diluted in the same medium (23), and 1 ml was added to 1 g of the sediment containing Aroclor 1242 dechlorination products to give a density of 104 (low-density treatment) or 106 (high-density treatment) cells g−1 of sediment for each recombinant strain. Noncontaminated sediment and noninoculated contaminated sediment subjected to the same conditions were used as controls. Flasks (20 ml) were continually shaken at 150 rpm and incubated in triplicate at 30°C for a period of 30 days. Each flask was opened once a week to ensure aerobic conditions. Sediment samples were stored at −20°C for DNA and PCB extractions. For the PCB analyses, duplicate samples of each treatment were sacrificed at predetermined time intervals, extracted, and analyzed by gas chromatography as previously described (31).

Bacterial counts.

Prior to inoculation with the transformants, total bacterial counts in the aerobic sediment microcosms were performed by staining with 5-(4,6-dichlorotriazine-2-yl) aminofluorescein (DTAF) followed by epifluorescence microscopy (5). Immediately after inoculation and after 10, 15, and 30 days of incubation, the transformants were counted by plating on selective medium. Samples taken for this purpose were immediately diluted, and appropriate dilutions were spread on Luria-Bertani agar containing rifampin (50 μg/ml). CFU for both strains were determined after 1 week of incubation.

DNA extraction and real time-PCR analysis.

Total sediment DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions, using an Ultraclean Soil DNA extraction kit (MoBio, Inc., Solana Beach, CA), and used for monitoring both recombinant strains by real-time PCR. Probe and primer sequences for real-time PCRs were designed using Primer Express software (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). The probe contained 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) as a reporter fluorochrome on the 5′ end and TAMRA (N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-6-carboxyrhodamine) as a quencher on the 3′ end of the nucleotide sequence (Table 1). PCR was carried out in the spectrofluorimetric thermal cycler of the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A standard curve was previously generated from changes in the fluorescence reporter signal (ΔRn) versus the cycle number during PCR, allowing determination of the threshold cycle (CT) (32).

Stability of fcb and ohb genes.

Each time the CFU of recombinant bacteria from the sediment microcosms were determined by plating on Luria-Bertani agar containing rifampin (50 μg/ml), the proportions of fcb- and ohb-containing colonies were determined by picking 10 colonies of each strain and screening for the fcb or ohb gene by PCR amplification. Template DNA for PCR was prepared by lysing whole cells in 100 μl 0.05 N NaOH at 95°C for 15 min. Primers were specifically designed for the fcbB and ohb genes (Table 1) to yield PCR products of 599 and 580 bp, respectively. Amplifications were performed in 20-μl reaction mixtures containing 10 pmol of each primer, a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 400 ng/ml of bovine serum albumin, 1× Taq buffer, 1.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 2 μl of DNA template. PCR was initiated with a 3-min denaturation step at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles with a denaturation temperature of 94°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 55°C for fcbB and 58°C for ohb for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 2.1 min, with a final extension for 5 min. Three-microliter aliquots of the PCR products were analyzed in 1% agarose gels.

RESULTS

Construction of strain LB400(ohb) with expanded metabolic capabilities.

The ohb operon, coding for oxygenolytic ortho dehalogenation (38), was cloned into the vector pRT1, yielding pRO41. Transformation of strain LB400 by electroporation with pRO41 enabled cells to grow on LB agar plates containing tetracycline (10 μg/ml). Transformants, now named LB400(ohb), were replicated on K1 agar-tetracycline plates with 1 mM of 2-CBA as the sole carbon source. Whole-cell PCR amplification with ohb-specific primers confirmed the presence of the targeted catabolic genes in the transformants (data not shown). The strain LB400(ohb) grew in K1 liquid medium containing 2-CBA as the sole carbon source and released stoichiometric amounts of chloride. The complete disappearance of 2-CBA was confirmed by HPLC. Controls of the LB400 strain transformed with a plasmid without ohb genes (pRT1) did not grow in medium containing 2-CBA.

Replated LB400(ohb) cells were morphologically (colony and cell) and phenotypically very similar to the parental strain LB400, maintaining the capability of growing on biphenyl, benzoate, 2-CB, 4-CB, and 2,4-CB. The 16S rRNA gene from LB400(ohb) was PCR amplified and partially sequenced, verifying the identity of the recombinant strain (data not shown).

Growth on synthetic PCB mixtures M and C.

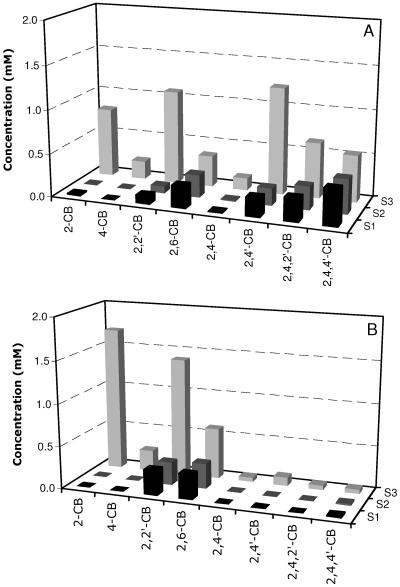

Cells of the wild-type strain LB400 and its recombinant, LB400(ohb), both previously grown on biphenyl, degraded 94% of the PCBs in mix C (Fig. 1A). The recombinant strain, LB400(ohb), grew to a final OD600 of 1.1 and did not accumulate 2-CBA or 2,4-CBA, whereas the wild-type strain LB400 grew to an OD600 of 0.74 and accumulated 3.27 mM and 0.11 mM of 2- and 2,4-CBA, respectively. Final concentrations of 4-CBA were similar for both the wild-type (0.18 mM) and transformant (0.13 mM) strains, with no utilization of this metabolite in either case. HOPDA concentrations were 38% less for the recombinant strain. The total chloride concentration was 4.1 mM for LB400(ohb) and 1.8 mM for the wild-type strain.

FIG. 1.

Degradation of defined artificial PCB mixtures M (A) and C (B) by recombinant B. xenovorans strain LB400(ohb) (S1) and its wild type (S2). Bars shown for S3 correspond to noninoculated controls. Data are mean values from duplicate samples.

Similar degradation was obtained for wild-type LB400 (79%) and recombinant LB400(ohb) (75%) when a 5 mM nominal concentration of PCB mixture M was used (Fig. 1B). Both strains grew on mix M, with OD600 values of 1.0 and 0.88 for LB400(ohb) and LB400, respectively. Once more, there was no accumulation of 2-CBA for LB400(ohb), whereas the wild-type strain LB400 accumulated 1.56 mM of 2-CBA. The total chloride concentration was 7.6 mM for LB400(ohb) and 4.6 mM for the wild-type strain. These results confirm that LB400(ohb) could more completely metabolize and grow on these PCBs.

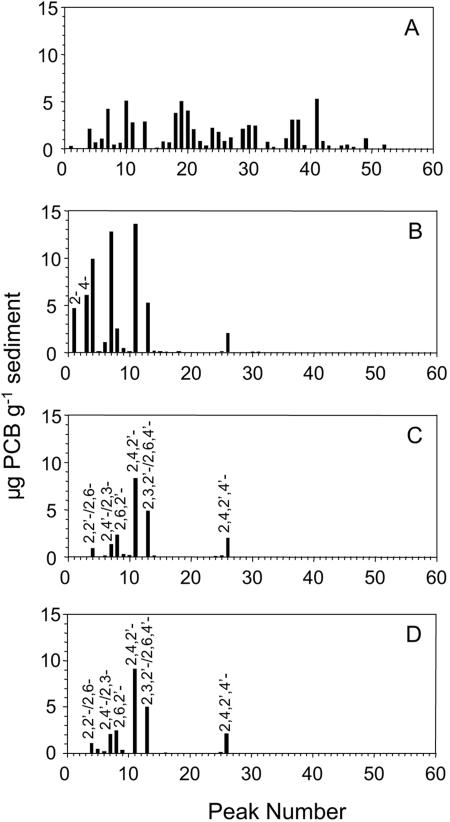

Anaerobic PCB dechlorination.

During the 1-year anaerobic incubation, River Raisin microorganisms removed 32% of the chlorine from Aroclor 1242, primarily from the meta positions. The resulting congener profile was very similar to that of pattern M, with the exception that 2,4,4′-CB did not accumulate (Fig. 2). While there was no indication that the biphenyl moiety was degraded, the total PCB concentration on a weight basis (μg/g sediment) decreased 14.2% as a result of dechlorination.

FIG. 2.

Aroclor 1242 congener distribution and concentration (μg g−1) in contaminated sediment at time zero (A) or after 1 year of incubation under anaerobic conditions (B), followed by aerobic incubation for 30 days with recombinant strains RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb) at 106 cells g−1 of sediment (C) or 104 cells g−1 (D). See reference 31 for PCB congeners represented by each peak.

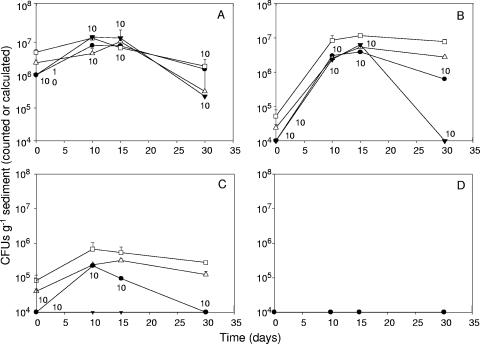

Population dynamics of recombinant RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb) strains.

Direct bacterial counts of the sediment before inoculation averaged 4.82 × 108 cells g−1 sediment. No indigenous sediment bacteria could be isolated in rifampin-containing medium at our detection limit of 102 cells g−1 soil (Fig. 3D). Because of their distinctive colonies on plates, we were able to count both the recombinant Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1(fcb) and the recombinant B. xenovorans strain LB400(ohb). Bacterial counts increased for both high (106 cells per gram of sediment)- and low (104 cells per gram of sediment)-density inoculation treatments when PCBs were present (Fig. 3A and B). With the high-density inoculation treatment, the RHA1(fcb) cell number increased to 7.8 × 106 rifampin-resistant cells g−1 sediment, while the LB400(ohb) cell number increased to 1.4 × 107 cells g−1 sediment. We found approximately 3.8 × 106 and 6.2 × 106 cells g−1 sediment for RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb), respectively, in the low-density treatment at day 15. No LB400(ohb) colonies could be detected on agar medium with the noncontaminated treatment, while RHA1(fcb) colonies increased from 1.0 × 104 to only 2.2 × 105 cells g−1 soil on day 10 (Fig. 3C). Neither cell type appeared on plates with the noninoculated, PCB-containing control (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Population densities of recombinant strains Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1(fcb) (•) and B. xenovorans strain LB400(ohb) (▾), containing the fcb and ohb operons, respectively, inoculated into Aroclor 1242-contaminated sediment that had previously undergone anaerobic PCB dechlorination. Cell numbers were also estimated by real-time PCR with TaqMan fcb (□) and TaqMan ohb (▵) probes. (A) Inoculation density of 106 cells g−1 sediment for each strain. (B) Inoculation density of 104 cells g−1 sediment for each strain. (C) Noncontaminated control with inoculation density of 104 cells g−1 sediment for each strain. (D) Noninoculated control. The value above each sampling time represents the stability of the fcb or ohb operon in 10 randomly chosen colonies from each strain when isolation was possible above the detection limit. Where error bars are not shown, the standard error of triplicates was smaller than the size of the symbol.

Monitoring RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb) by real-time PCR.

We used a threshold cycle (CT) cutoff value of 32 for negative amplification, based on previous testing (not shown). The real-time PCR results correlated well with plate count data. The calculated CFU g−1 of sediment for RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb), using the TaqMan fcb and ohb probes, were 4.5 × 106 and 4.4 × 107 cells g−1 of sediment, respectively, on day 15 for the high-inoculation density treatment (Fig. 3A). For the low-density inoculation, the calculated number of CFU g−1 also increased for both recombinant strains, reaching similar values on day 15 for RHA1(fcb) (5.3 × 106) and LB400(ohb) (4.4 × 106) (Fig. 3B). We also found approximately 3.1 × 105 cells g−1 of RHA1(fcb) in samples obtained from the PCB-free sediment, whereas calculated cell numbers for LB400(ohb) were below the detection limit after day 10 (Fig. 3C). Sediment samples taken from noninoculated controls did not yield any increment in fluorescence above the threshold (Fig. 3D).

Stability of fcb and ohb operons.

The fcb and ohb operons in strains RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb), respectively, appeared to be stable in soil in the absence of antibiotics. In fact, PCBs are formally selective. All screened colonies but one LB400(ohb) colony resulted in PCR-amplified products (Fig. 3A, B, and C) of the expected sizes of 599 bp and 580 bp from RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb) cell lysates, respectively. In addition, the same isolated colonies of LB400(ohb) and RHA1(fcb) which gave positive amplification of PCR products grew on solid media containing 2-CBA or 4-CBA as the only carbon source, respectively. All colonies retained the capability of growing on biphenyl.

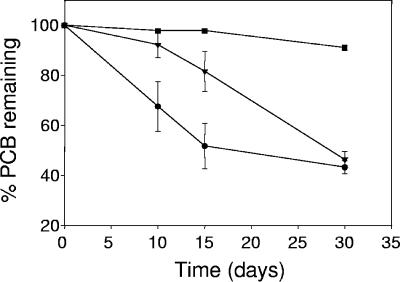

The degradation of dechlorinated Aroclor 1242 was effective for both low- and high-density inoculation treatments (Fig. 4), although, as expected, it was slightly faster with the high-density inoculum. However, after 30 days, the PCB removal rates for high and low inoculation densities were 57% and 54%, respectively. Only a small amount of PCBs (4%) was degraded in the noninoculated treatment, indicating that the inoculated recombinant strains were responsible for the degradation of anaerobic products of Aroclor 1242 dechlorination. The major congeners not degraded were 2,2′-/2,6-, 2,4′-, 2,4,2′-, 2,6,2′-, 2,6,4′-, and 2,4,2′,4′-chlorobiphenyl (Fig. 2C and D). Final concentrations of PCBs were 24.4 and 26.8 μg per g of sediment for the high and low density inoculums, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Percentages of PCBs remaining during aerobic treatment with recombinant strains RHA1(fcb) and LB400(ohb) after incubation with two different inoculum densities. Symbols: •, 106 cells of each strain g−1 of sediment; ▾, 104 cells of each strain g−1 of sediment; ▪, noninoculated control. Duplicate samples were used for the noninoculated control. Where error bars are not shown, the standard error of triplicates was smaller than the size of the symbol.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we showed that the recombinant strain RHA1(fcb) could grow in freshly contaminated soil with a single PCB congener, 4-CB, and that growth correlated with the disappearance of this contaminant (33). Here, Aroclor 1242-contaminated sediments were incubated with consortia from a PCB-dechlorinating sediment for 1 year, and the PCB dechlorination products were used as substrates for the aerobic phase of PCB degradation, using RHA1(fcb) plus a newly constructed strain with different PCB congener specificities.

We previously used an alternative approach for the construction of PCB-degrading bacteria through in vitro pathway generation with the introduction of specific chlorobenzoate degradation genes and funneling of PCBs into substrates for preexisting central metabolic pathways for Comamonas testosteroni strain VP44 (27) and Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 (32, 33). For this study, we used the same approach but substituted the well-characterized PCB-degrading B. xenovorans strain LB400 for strain VP44 because of LB400's preferential attack of ortho-substituted rings (23), which are the most prominent and problematic products of anaerobic PCB dechlorination (3). Cloning of the oxygenolytic ortho dehalogenation (ohb) genes in LB400 was possible through the same gram-positive/gram-negative shuttle vector pRT1 used for RHA1(fcb), attesting its utility for constructing PCB degraders of different genera. The ability of the novel recombinant strain LB400(ohb) to grow on 2 mM 2-CBA with 100% release of chloride indicated that the ohb operon was expressed. Furthermore, concatenated expression of the bph (biphenyl) and ohb pathways was observed during growth of LB400(ohb) on 5 mM of PCB mixtures M and C, with no accumulation of 2-CBA. Efficiencies in utilizing these mixtures were similar for both parental LB400 and its recombinant, LB400(ohb) (Fig. 1), with the latter showing better growth along with complete mineralization of 2-CBA.

In assessing the suitability of LB400(ohb) for use in an anaerobic/aerobic biotreatment process, we compared its abilities to degrade PCB mixes M and C. Pattern M PCB profiles result from the microbially mediated dechlorination of Aroclor 1242 and other lesser chlorinated commercial PCB mixtures from the meta positions. Thus, pattern M is a mixture of predominantly ortho- and para-substituted congeners. It is robust, apparently being mediated by a spore-forming microorganism (40), and is widely distributed in the environment. Process Q removes chlorines from para positions, and pattern C, comprised of mainly ortho-substituted congeners, results from the combined activities of processes M and Q (3). Dechlorination of Aroclors from the ortho positions is exceedingly rare, and there is no clear evidence that it has happened in nature. Thus, mixtures of PCB congeners approximating patterns M and C are appropriate for testing the aerobic biodegradation capabilities of microorganisms to be used in anaerobic/aerobic biotreatment processes: M is useful because it is more readily achievable, and C represents the most extensively dechlorinated mixture achievable.

LB400(ohb) degraded 94% of the PCBs in mix C and 75% of the PCBs in mix M. Thus, there is an advantage in achieving more extensive PCB dechlorination in the anaerobic stage of an anaerobic/aerobic biotreatment process for PCBs. Still, because of its wide substrate range, LB400(ohb) can be expected to effect a substantial decrease in PCB concentration during the aerobic phase, even when anaerobic dechlorination is limited to the meta positions.

The two-step anaerobic/aerobic PCB bioremediation treatment was then tested in Aroclor 1242-contaminated river sediment, using the newly constructed B. xenovorans strain LB400(ohb), with its ortho dechlorination capacities, and Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1(fcb), with its para dechlorination capacities. Firstly, we confirmed that the anaerobic process took place with the expected shifts in the patterns of the different congeners (Fig. 2A and B), with no loss of PCBs on a total molar basis but with a significant reduction of the total weight of PCBs (14.2%) due to the removal of chlorines (30, 31). Secondly, both recombinant strains grew to approximately 106 CFU per gram of sediment after 15 days (Fig. 3A and B), although RHA1(fcb) cells grew 1 order of magnitude in noncontaminated microcosm samples (Fig. 3C), suggesting that while this strain could grow on substrates already present in sediment, it grew better when its unique substrates, i.e., PCB dechlorination products, were present. Strain LB400(ohb) grew even more extensively under the same conditions, consistent with its ability to grow on some of the ortho-chlorinated PCBs, the more prevalent products of anaerobic dechlorination of Aroclor 1242.

Real-time PCR data confirmed the same population growth pattern observed by plate counts (Fig. 3A, B, and C). The difference between plate counts and the estimated number of RHA1(fcb) cells by real-time PCR was <1 order of magnitude, supporting the reliability of both methods. Furthermore, other studies of these samples using DNA microarrays containing probes for the aromatic oxygenase genes present in the bph, fcb, and ohb pathways gave similar quantitative results (8). The consistency of the data for all three methods plus the expected consumption of substrates argues that the recombinant strains grew successfully when added to the natural, indigenous community.

Since inoculation is an expensive component of bioremediation technology, we tested moderate and low inoculation densities. Xenobiotic degradation and survival of strains in soils have usually been studied with inoculation densities much higher than the soils' carrying capacities for those strains. Inevitably, in such cases, cell numbers decrease by 4 to 6 orders of magnitude in a small period of time (14, 18, 22, 36). This was not the case for our experiments, since we inoculated samples at relatively low cell densities and were able to see an increase in cell numbers (Fig. 3A and B). Our results, especially with an inoculum goal of 104 cells per gram of soil, indicate that the same rate and extent of biodegradation can be obtained at a reasonable scale-up cost.

Thus, the primary advantage of PCB-growing strains is that the maintenance of an adequate PCB-degrading population should occur and would avoid either the repeated inoculation of strains into the contaminated site (12) or the use of a second carbon source to stimulate cometabolism, such as biphenyl (2, 13), surfactants (20, 21), or plant aromatic compounds (11). For this approach to be successful, however, the plasmid constructs must remain stable, which was the case over the course of our experiment (Fig. 3A, B, and C). Although biphenyl-degrading bacteria can be easily found in soil, chlorobenzoate degraders with the needed substrate specificities are relatively rare (10), and the activities of inoculated chlorobenzoate degraders during PCB degradation resulted in higher mineralization rates in liquid and soil experiments (14, 15), providing further evidence of benefit from the constructed strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jamie K. VanderWal for technical assistance and Frank Löffler for stimulating discussions during the course of the experiments.

J.L.M.R. recognizes financial support from CAPES-Brazil (project BEX 0378/95-3). This project was supported by the NIEHS Superfund Basic Research Program (P42 ES 04911), the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) Bioconsortium, and the NSF Center for Microbial Ecology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, R. H., C.-H. Huang, F. K. Higson, V. Brenner, and D. D. Focht. 1992. Construction of a 3-chlorobiphenyl-utilizing recombinant from an intergeneric mating. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:647-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barriault, D., and M. Sylvestre. 1993. Factors affecting PCB degradation by an implanted bacterial strain in soil microcosms. Can. J. Microbiol. 39:594-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedard, D. L., and J. F. Quensen III. 1995. Microbial reductive dechlorination of polychlorinated biphenyls, p. 127-216. In L. Y. Young and C. E. Cerniglia (ed.), Microbial transformation and degradation of toxic organic chemicals. Wiley-Liss, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Bergmann, J. G., and J. Sanik, Jr. 1957. Determination of trace amounts of chlorine in naphtha. Anal. Chem. 29:241-243. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloem, J. 1995. Fluorescent staining of microbes for total direct counts, 4.1.8.1-4.1.8.12. In A. D. L. Akkermans, J. D. V. Elsas, and F. J. D. Bruijn (ed.), Molecular microbial ecology manual, 2nd ed. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 6.Bopp, L. H. 1986. Degradation of highly chlorinated PCBs by Pseudomonas strain LB400. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1:23-29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, J. F., Jr., R. E. Wagner, D. L. Bedard, M. J. Brennan, J. C. Carnahan, R. J. May, and T. J. Tofflemire. 1984. PCB transformations in upper Hudson sediments. Northeast. Environ. Sci. 3:167-179. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denef, V. J., J. Park, J. L. M. Rodrigues, T. V. Tsoi, S. A. Hashsham, and J. M. Tiedje. 2003. Validation of a more sensitive method for using spotted oligonucleotide DNA microarrays for functional genomic studies on bacterial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 5:933-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fish, K. M., and J. M. Principe. 1994. Biotransformations of Aroclor 1242 in Hudson River test tube microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4289-4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Focht, D. D. 1995. Strategies for the improvement of aerobic metabolism of polychlorinated biphenyls. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 6:341-346. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert, E. S., and David E. Crowley. 1997. Plant compounds that induce polychlorinated biphenyl biodegradation by Arthrobacter sp. strain B1B. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1933-1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein, R. M., L. M. Mallory, and M. Alexander. 1985. Reasons for possible failure of inoculation to enhance biodegradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50:977-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harkness, M. R., J. B. McDermott, D. A. Abramowicz, J. J. Salvo, W. P. Flanagan, M. L. Stephens, F. J. Mondello, R. J. May, J. H. Lobos, and K. M. Carroll. 1993. In situ stimulation of PCB aerobic biodegradation in Hudson River sediments. Science 259:503-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havel, J., and W. Reineke. 1993. Degradation of Aroclor 1221 in soil by a hybrid pseudomonad. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 108:211-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hickey, W. J., D. B. Searles, and D. D. Focht. 1993. Enhanced mineralization of polychlorinated biphenyls in soil inoculated with chlorobenzoate-degrading bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1194-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holoubek, I. 2001. Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) contaminated sites worldwide, p. 17-26. In L. W. Robertson and L. G. Hansen (ed.), PCBs, recent advances in environmental toxicology and health effects. The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky.

- 17.Hrywna, Y., T. V. Tsoi, O. V. Maltseva, J. F. Quensen, and J. M. Tiedje. 1999. Construction and characterization of two recombinant bacteria that grow on ortho- and para-substituted chlorobiphenyls. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2163-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huertas, M.-J., E. Duque, S. Marques, and J. L. Ramos. 1998. Survival in soil of different toluene-degrading Pseudomonas strains after solvent shock. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:38-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutzinger, O., and W. Veerkamp. 1981. Xenobiotic chemicals with pollution potential, p. 3-45. In T. Leisinger, R. Hutter, A. M. Cook, and J. Nuesch (ed.), Microbial degradation of xenobiotics and recalcitrant compounds. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 20.Lajoie, C. A., G. J. Zylstra, M. F. DeFlaun, and P. F. Strom. 1993. Development of field application vectors for bioremediation of soils contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1735-1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lajoie, C. A., A. C. Leyton, and G. S. Sayler. 1994. Cometabolic oxidation of polychlorinated biphenyls in soil with a surfactant-based field application vector. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2826-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung, K. T., A. Watt, H. Lee, and J. K. Travors. 1997. Quantitative detection of pentachlorophenol-degrading Sphingomonas sp. UG30 in soil by a most-probable-number/polymerase chain reaction protocol. J. Microbiol. Methods 31:59-66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maltseva, O. V., T. V. Tsoi, J. F. Quensen III, M. Fukuda, and J. M. Tiedje. 1999. Degradation of anaerobic reductive dechlorination products of Arochlor 1242 by four aerobic bacteria. Biodegradation 10:363-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masai, E., A. Yamada, J. M. Healy, T. Hatta, K. Kimbara, M. Fukuda, and K. Yano. 1995. Characterization of biphenyl catabolic genes of gram-positive polychlorinated biphenyl degrader Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2079-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Master, E. R., V. W.-M. Lai, B. Kuipers, W. R. Cullen, and W. W. Mohn. 2002. Sequential anaerobic-aerobic treatment of soil contaminated with weathered Aroclor 1260. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:100-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCullar, M. V., V. Brenner, R. H. Adams, and D. D. Focht. 1994. Construction of a novel polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading bacterium: utilization of 3,4′-dichlorobiphenyl by Pseudomonas acidovorans M3GY. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3833-3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mokross, H., E. Schimidt, and W. Reineke. 1990. Degradation of 3-chlorobiphenyl by in vivo constructed hybrid pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 71:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mondello, F. J. 1989. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of Pseudomonas strain LB400 genes encoding polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. J. Bacteriol. 171:1725-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potrawfke, T., T. H. Lohnert, K. N. Timmis, and R. M. Wittich. 1998. Mineralization of low-chlorinated biphenyls by Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 and by a two membered consortium upon directed interspecies transfer of chlorocatechol pathway genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 50:440-446. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quensen, J. F., III, J. M. Tiedje, and S. A. Boyd. 1988. Reductive dechlorination of polychlorinated biphenyls by anaerobic microorganisms from sediments. Science 242:752-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quensen, J. F., III, S. A. Boyd, and J. M. Tiedje. 1990. Dechlorination of four commercial polychlorinated biphenyl mixtures (Aroclors) by anaerobic microorganisms from sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2360-2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigues, J. L. M., M. R. Aiello, J. Urbance, T. V. Tsoi, and J. M. Tiedje. 2002. Use of both 16S rRNA and engineered functional genes with real time PCR to quantify an engineered, PCB-degrading Rhodococcus in soil. J. Microbiol. Methods 51:181-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodrigues, J. L. M., O. V. Maltseva, T. V. Tsoi, R. R. Helton, J. F. Quensen III, M. Fukuda, and J. M. Tiedje. 2001. Development of a Rhodococcus recombinant strain for degradation of products from anaerobic dechlorination of Aroclor 1242. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35:663-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shelton, D. R., and J. M. Tiedje. 1984. General method for determining anaerobic biodegradation potential. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47:850-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith, M. S., and J. M. Tiedje. 1980. Growth and survival of antibiotic-resistant denitrifier strains in soil. Can. J. Microbiol. 26:854-856. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tchelet, R., R. Meckenstock, P. Steinle, and J. R. van der Meer. 1999. Population dynamics of an introduced bacterium degrading chlorinated benzenes in a soil column and in sewage sludge. Biodegradation 10:113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tiedje, J. M., T. V. Tsoi, K. D. Pennel, L. D. Hansen, A. Wani, J. L. M. Rodrigues, Y. Hrywna, and D. P. Howell. 2005. Enhancing PCB bioremediation, p. 147-214. In J. W. Talley (ed.), Bioremediation of recalcitrant compounds. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 38.Tsoi, T. V., E. G. Plotnikova, J. R. Cole, W. F. Guerin, M. Bagdasarian, and J. M. Tiedje. 1999. Cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 142 ohb genes coding for oxygenolytic ortho dehalogenation of halobenzoates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2151-2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unterman, R. 1996. A history of PCB degradation, p. 209-253. In R. L. Crawford and D. L. Crawford (ed.), Bioremediation principles and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 40.Ye, D., J. F. Quensen III, J. M. Tiedje, and S. A. Boyd. 1992. Anaerobic dechlorination of polychlorobiphenyls (Aroclor 1242) by pasteurized and ethanol-treated microorganisms from sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1110-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zaitsev, G. M., T. V. Tsoi, V. G. Grishenkov, E. G. Plotnikova, and A. M. Boronin. 1991. Genetic control of degradation of chlorinated benzoic acids in Arthrobacter globiformis, Corynebacterium sepedonicum and Pseudomonas cepacia strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 81:171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zwiernik, M. J., J. F. Quensen III, and S. A. Boyd. 1998. FeSO4 amendments stimulate extensive anaerobic PCB dechlorination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32:3360-3365. [Google Scholar]