Abstract

This study examined the bioenergetics of Listeria monocytogenes, induced to an acid tolerance response (ATR). Changes in bioenergetic parameters were consistent with the increased resistance of ATR-induced (ATR+) cells to the antimicrobial peptide nisin. These changes may also explain the increased resistance of L. monocytogenes to other lethal factors. ATR+ cells had lower transmembrane pH (ΔpH) and electric potential (Δψ) than the control (ATR−) cells. The decreased proton motive force (PMF) of ATR+ cells increased their resistance to nisin, the action of which is enhanced by energized membranes. Paradoxically, the intracellular ATP levels of the PMF-depleted ATR+ cells were ∼7-fold higher than those in ATR− cells. This suggested a role for the FoF1 ATPase enzyme complex, which converts the energy of ATP hydrolysis to PMF. Inhibition of the FoF1 ATPase enzyme complex by N′-N′-1,3-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide increased ATP levels in ATR− but not in ATR+ cells, where ATPase activity was already low. Spectrometric analyses (surface-enhanced laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry) suggested that in ATR+ listeriae, the downregulation of the proton-translocating c subunit of the FoF1 ATPase was responsible for the decreased ATPase activity, thereby sparing vital ATP. These data suggest that regulation of FoF1 ATPase plays an important role in the acid tolerance response of L. monocytogenes and in its induced resistance to nisin.

Listeria monocytogenes causes ∼2,500 cases/year of listeriosis out of an estimated 76 million cases/year of food-borne disease in the United States (23). The pathogen targets mainly newborn, pregnant, elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, and it is associated with mortality rates of up to 37%. Control of L. monocytogenes is difficult, due to its widespread presence in nature, intrinsic physiologic resistance, adaptation capacity, and ability to grow at low temperatures (37).

The responses of L. monocytogenes to acid, osmotic, and thermal stresses increase its resistance and virulence (16, 28). The acid tolerance response (ATR) is the abnormal resistance to lethal acid after an exposure to mild acidic conditions (21). The regulation of stress response proteins changes during induction of the ATR (29, 31). These proteins include chaperones, transcriptional regulators (13), the glutamic acid decarboxylase system, and the FoF1 ATPase enzyme complex (10, 31). The ATR also increases virulence and cross-protects listeriae from other stressors, such as elevated temperatures (16) and antimicrobials (28).

The specific acids affect the pH range at which the ATR is induced and the range within which the pH becomes lethal; lactic acid is a stronger inducer than HCl (2). The ATR also confers resistance to the bacteriocin nisin, an antimicrobial peptide that is approved for food use in >40 countries (6). ATR-induced L. monocytogenes cells (ATR+) but not the control cells (ATR−) survive for at least 30 days at 4°C in a model fermented system where Lactococcus lactis produced lactic acid (pH 5.7) and nisin (50 μg/ml) (2). The mechanism by which the ATR protects L. monocytogenes against nisin is uncertain. Analysis of membrane lipids of constitutively nisin-resistant listeriae shows that their membrane is more rigid, due to changes in the proportion of fatty acids (11, 24, 25). Similar temperature-induced changes in membrane composition cause measurable changes in membrane fluidity as demonstrated by fluorescence anisotropy (22). However, these changes in membrane lipid composition do not fully explain the increased nisin resistance of ATR+ listeriae (38).

Cell membranes have low permeability to protons, which are subjected to specific transport mechanisms such as FoF1 ATPase, Na+/H+ antiporters, and electron transport systems (31). This enables living cells to build a potential across their membranes, which is essential for energy transduction (41). The peptide nisin targets energized cell membranes, and its insertion is activated by the difference in free available energy across the membrane (12). Nisin molecules insert cooperatively into the cell membrane, which is disrupted by transient pore formation (4). Destruction of the membrane integrity collapses the proton motive force (PMF), causing cell death.

The PMF-dependent action of nisin suggested a bioenergetic contribution to nisin resistance in ATR+ listeriae. We hypothesized that decreased PMF contributes to the increased nisin resistance of ATR+ L. monocytogenes. In L. monocytogenes, the PMF is generated primarily by the membrane-associated FoF1 ATPase, which builds a PMF using energy derived from ATP hydrolysis (8). We present surprising evidence that ATR+ listeriae have significantly higher intracellular ATP (ATPi) concentrations than ATR− cells. This vital ATP sparing in ATR+ L. monocytogenes is correlated to the downregulation of the FoF1 ATPase c subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, cultivation conditions, and chemicals.

L. monocytogenes Scott AR (serotype 4b, containing plasmid pGK12) was originally obtained from P. Foegeding (North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC) (14) and maintained as described in our previous studies (2). Broth cultures were prepared in tryptic soy broth augmented with 0.5% yeast extract (TSBYE) and incubated statically for 18 h at 37°C. Unless otherwise noted, TSBYE acidification was done using 30% (vol/vol) l-(+)-lactic acid (80% [wt/vol] commercial solution; Purac America, Lincolnshire, IL). All pH measurements were conducted using a recording potentiometer (Markson, Honolulu, HI) at 20°C. Acidified media, solutions, and supernatants were sterilized using 0.20-μm membrane filters (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). Dehydrated media and their major components were acquired from Difco/Becton Dickinson and Company. Inorganic substances, enzymes, nisin preparation, antibiotics, and ionophors were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Fluorescent probes were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Induction of ATR in L. monocytogenes.

The ATR was induced as previously described. Briefly, 10 μl of a stationary-phase TSBYE Listeria monocytogenes Scott AR culture (which had been inoculated with a loopful of the agar slant stock culture and incubated for 18 h at 37°C) was used to inoculate TSBYE (40 ml) and incubated at 37°C until early-exponential-growth phase (A600 = 0.1; 4.1 × 107 CFU/ml). Cells were centrifuged (5,095 × g at 4°C for 10 min) and resuspended in an equal volume of TSBYE at pH 7.0 (ATR−; control) or in TSBYE acidified with lactic acid to pH 5.5 (ATR+ induction) at 37°C for 60 min.

Determination of intracellular pH (pHi). (i) Cell preparation and probe uptake.

Determinations of pHi were conducted using the probe BCECF-AM [2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5- and -6)-carboxyfluorescein, acetoxymethyl ester]. ATR+ or ATR− L. monocytogenes (10 ml) was centrifuged at 5,095 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and the pellets were suspended in 500 μl potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM) at pH 5.5 or pH 7.0, respectively. Suspensions were washed twice (10,000 × g for 30 s) using the respective buffer. Aliquots (each, 200 μl) were collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 30 s) and resuspended in 20 μl buffer containing 1 μl of BCECF-AM solution (50 μg BCECF-AM dissolved in 8 μl dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). After 15 min at room temperature to allow for probe uptake and hydrolysis by cell esterases, preparations were washed twice, each time in 500 μl of the appropriate buffer, and resuspended.

(ii) Calibration curves for pHi.

Individual calibration curves (to account for different cell numbers in the ATR+ and ATR− preparations) correlating pHi and fluorescence were obtained by measuring the fluorescence (Fluorescent Spectrometer model LS50B; Perkin-Elmer Instruments, Shelton, CT) of each cell preparation at various external pH values (pHo). Potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM) at pH 7.0 or acidified to pH 6.5, 6.0, or 5.5 was used to establish pHo values. Cuvettes containing 2,000 μl of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer at the appropriate pHo were aliquoted with 50 μl of a 20% (wt/vol) glucose solution to give a final concentration of 0.5% (wt/vol). Cells (3.3 μl) were added to the cuvettes at time zero, and the fluorescence emitted by the internalized BCECF-AM was measured. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 502 and 525 nm, and band-pass widths were 5.0 and 10.0 nm, respectively. One microliter of a 5 mM nigericin solution (final concentration, 2.4 μM) was added to the cuvette at 60 s to collapse the ΔpH. The fluorescence signal after the ΔpH collapse stabilized (i.e., pHo = pHi) was averaged (>100 data points) and correlated with the imposed pHo by regression analysis. The assay was conducted at 22°C for 100 s, with readings every 0.1 s. The resulting fluorescence versus pH calibration curves specific to the ATR+ or ATR− cells were used to determine the pHi values of the respective cultures.

The PMF, measured in millivolts, was calculated according to equation 1 (5, 26):

|

(1) |

(iii) Effect of nisin on intracellular pH.

To assess pHi during exposure to nisin, 12.3 μl of a nisin solution (10 mg/ml, to give a final concentration of 50 μg/ml) was added at time zero to a cuvette containing the cell preparations in acidified buffer and glucose, as described above.

Determination of transmembrane electric potentials (Δψ). (i) Assay optimization and cell preparation.

Transmembrane electric potentials (Δψ) were determined at 22°C using the fluorescent probe 3,3′-dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide (di-S-C3) (5). Prior to determinations, the A643 values of various di-S-C3 (5) and cell concentrations were evaluated to optimize assay conditions and to avoid inner filter effects (the scattering and absorption of the excitation and emitted light by turbid material). Briefly, solutions of the probe ranging from 490 to 4,900 nM were prepared in 50 mM sodium-HEPES-morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer and their A643 values were measured in the absence and presence of cell suspensions (A600 = 0.19; 9 × 107 CFU/ml). Once the extinction coefficient (ɛ) of the probe and optimal assay conditions were established, 10 ml of ATR+ or ATR− cells was washed twice (5,095 × g at 4°C for 10 min), suspended to an A600 of 0.19 using 50 mM potassium-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 7.0 or 5.5, respectively, and kept ice cold.

(ii) Estimation of [K+]i.

Intracellular potassium concentrations [K+]i must be determined to calculate Δψ (37). The fluorescence of cells suspended in buffers ranging from 0 to 250 mM extracellular potassium [K+]o was evaluated after the addition of the potassium uniporter valinomycin. To impose various [K+]o values, appropriate amounts of 3.0 F KCl were added to 50 mM sodium-HEPES-MES buffers at pH 5.5 (for ATR+) or pH 7.0 (for ATR−). The probe di-S-C3 (100 μM solution) (5) was added (10 μl; final concentration, 330 nM) to cuvettes containing 2,000 μl buffer at pH 7.0 (ATR−) or 5.5 (ATR+). Continuous fluorescence readings were made; at ∼60 s, 1,000 μl of ATR+ or ATR− cells (each previously resuspended in the test potassium concentration) was mixed into the cuvette. At ∼150 s, 12 μl of a 2 mM ethanolic valinomycin solution was added to a final concentration of 8 μM. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 643 and 666 nm, and band-pass widths were 5.0 and 10.0 nm, respectively. The assay was at 22°C for 300 s, with readings every 0.1 s.

The Δψ was determined from potassium diffusion potentials (39) as follows:

|

(2) |

(iii) Effect of nisin on transmembrane electric potential (Δψ).

Assays were conducted as described above, with modifications. Prior to fluorescence measurements, 75 μl of 20% (wt/vol) glucose solution (final concentration, 0.5% [wt/vol]) was added to cuvettes containing 2,000 μl of 50 mM potassium-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 5.5 or pH 7.0. The cell preparation (1,000 μl) was then added, followed by nigericin (1 μl of 5 mM ethanolic solution; final concentration, 1.6 μM) to eliminate the ΔpH component of the PMF. The cuvette was subjected to baseline fluorescence readings; at ∼40 s, 10 μl of 100 μM di-S-C3 (final concentration, 320 nM) (5) was added and quickly mixed in by pipetting. After probe equilibration, 15 μl of 10,000 IU nisin · ml−1 was mixed in to a final concentration of 50 μg ml−1. In some assays, valinomycin (8 μM) was added at 400 s to deplete residual Δψ. To establish a background fluorescence level, assays were also performed with dead cells (autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min) of the corresponding cell preparations.

(iv) De novo protein synthesis and response to nisin.

The influence of de novo protein synthesis on Δψ and cellular response to nisin was examined at pH 5.5 using elevated, inhibitory levels of chloramphenicol (70 μg/ml). Assays were conducted as described above, but the assay time was extended to 1,000 s. Nisin (final concentration, 50 μg · ml−1) was added at 650 s, followed by valinomycin (8 μM) at 800 s.

Determination of ATP levels.

ATP levels were determined by the luciferin-luciferase method previously described (24), with modifications. Calibration curves for luminescence versus ATP concentrations were generated by the addition of the enzyme-substrate preparation (diluted 1:10 with the dilution buffer provided) to serially diluted ATP standards in the same buffer, followed immediately by luminometry (Luminoskan TL Plus luminometer; Labsystems Oy, Helsinki, Finland). ATPi was determined as the difference between total ATP and extracellular ATP. ATR+ or ATR− cells were washed twice (each time, 5,095 × g at 4°C for 10 min) and resuspended at equal cell densities (A600 = 0.19) in 50 mM sodium-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 7.0 or 5.5, respectively, and kept ice cold. For determination of extracellular ATP, cell suspensions (each, 100 μl) were diluted 1:10 in 50 mM sodium-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 7.8, followed by the mixing of 100 μl with an equal volume of enzyme-substrate preparation in a round cuvette immediately before readings were carried out. To determine total (extracellular plus intracellular) ATP levels, 100-μl cell suspensions were diluted 1:10 in their respective suspension buffers and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 s. The resulting pellets were mixed with 10 μl DMSO for complete cell permeabilization (32). After 5 min of permeabilization at room temperature, 990 μl of 50 mM sodium-HEPES-MES buffer, pH 7.8, was added to the pellets to give a final volume of 1,000 μl. Samples (each, 100 μl) of these suspensions were mixed with equal amounts of enzyme-substrate preparation to determine their ATP concentrations.

Time-dependent examination of ATP levels in the presence of glucose and nisin.

ATP determinations in the presence of glucose (0.5% [wt/vol]) and nisin (50 μg ml−1) were conducted as described above with the following modifications. Portions (each, 1,000 μl) of ice-cold cell preparations were centrifuged (10,000 × g; 30 s) and resuspended (A600 = 0.19) in 50 mM sodium-HEPES-MES buffer (pH 5.5) containing glucose and nisin. At predetermined intervals, 100-μl portions were diluted 1:10 in 50 mM sodium-HEPES-MES buffer, pH 7.8, to decrease the nisin concentration and minimize its action and then centrifuged. Pellets were treated with 10 μl DMSO and resuspended in 1,000 μl buffer, and 100 μl was used for each luminescence assay. Controls were performed with glucose in the absence of nisin.

Role of the FoF1 ATPase complex on ATP levels.

ATP concentrations of cells treated with 1 mM N′-N′-1,3-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD), an FoF1 ATPase inhibitor (22), during ATR induction were determined as described above, except that 50 mM potassium-HEPES-MES buffers (containing 1 mM DCCD) were used to avoid the sodium-induced decrease of DCCD inhibitory activity (3).

Regulation of FoF1 ATPase. (i) Sample preparation for surface-enhanced laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (SELDI-TOF MS).

ATR+ or ATR− L. monocytogenes cells (100 ml) were centrifuged at 5,095 × g at 4°C for 10 min, washed in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM) at pH 5.5 or pH 7.0, respectively, and centrifuged again. The pellets were resuspended in 1 ml aqueous chloramphenicol solution (3.5 μg · ml−1) to inhibit de novo protein synthesis during sample preparation and frozen at −20°C overnight. The A600 was fixed at 0.50 (2.5 × 108 CFU/ml) by the addition of lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) to the resuspended pellets. Twenty milliliters of each preparation was subjected to 20,000 lb/in2 for 1 min with a French pressure cell. Protein was quantified by determination of the A280 value against a standard curve generated using bovine serum albumin (200 mg/ml; Sigma) in lysis buffer.

(ii) Chip preparation.

Samples (each, ca. 4 μl) having equal amounts of protein (6.6 μg) were spotted in quadruplicate on a hydrophobic H4 protein chip (Ciphergen Biosystems, Fremont, CA) and dried at room temperature for 15 min. The cocrystallization matrix was a saturated sinapic acid (Sigma-Fluka) solution prepared in equal volumes of 1% trifluoroacetic acid and 50% acetonitrile. Two microliters of the matrix was added to each spot prior to assay and allowed to dry for an additional 15 min.

(iii) Spectrometric analysis.

Samples were analyzed by mass spectrometry using a series PBS II ProteinChip reader (Ciphergen) with optimization between 2 and 15 kDa. Spectra from continuous laser excitation of three independent spots for each sample were averaged and analyzed.

(iv) Protein databases.

Computational studies were performed primarily using information on the Listeria monocytogenes complete genome available from the Pasteur Institute at http://genolist.pasteur.fr/ListiList/index.html and applicable links. Protein hydrophobicity plots were performed using Kite-Doolittle computations available at http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/molkit/hydropathy/.

Statistical analysis.

Experiments were reproducible and performed in at least duplicate unless stated otherwise. Where applicable, means were compared using Student's t test, and inferences were made at a 5% probability level.

RESULTS

pHi in ATR+ and ATR− cells; effect of nisin on pHi.

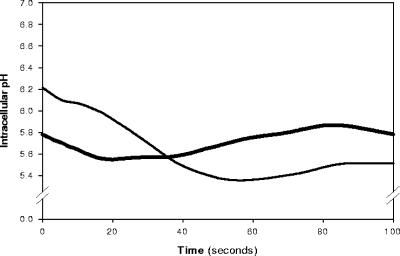

Intracellular pH values were calculated from separate calibration curves (r2 > 0.98) which accounted for the different cell densities of ATR+ and ATR− cells. When cell preparations were subjected to nisin and glucose at pH 5.5, the pHi of ATR+ listeriae at time zero was 5.8, resulting in a transmembrane pH (ΔpH) of −0.3 U. In contrast, ATR− cells had a higher initial pHi of 6.2, resulting in a ΔpH of −0.7 U (Fig. 1). The reduced ΔpH of the ATR+ cells decreased the action of nisin during at least the first 20 s. The pHi of the ATR− cells rapidly approached a pHo of 5.5. These results did not change in the absence of nisin (data not shown), indicating that pHi responses were due to the penetration of lactic acid.

FIG. 1.

Determination of pHi of ATR+ (thick line) or ATR− (thin line) L. monocytogenes suspended in potassium phosphate buffer at pHo 5.5 (acidified with lactic acid) containing 0.5% glucose. Cells were exposed to nisin (50 μg ml−1) from time zero. Data are averages of two independent and reproducible spectra.

Transmembrane electric potential (Δψ) in ATR+ and ATR− cells. (i) Assay optimization and cell preparation.

The Δψ component of the PMF was also examined. Assay conditions were optimized to avoid detrimental inner-filter effects, and the extinction coefficient (ɛ) of di-S-C3 (5) was determined. The initial optimal probe concentration was 490 nM. The 490 nM probe solution had an A643 value of 0.015, producing an extinction coefficient (ɛ) of 30,612 M−1 cm−1. The A643 increased to 0.07 as cell suspensions were added to a ratio of one part cell suspension to two parts buffer with probe, while the probe concentration fell to about 320 nM. These conditions (final A643, <0.10) ensured that inner-filter effects (15) were minimized.

(ii) Estimation of [K+]i.

Intracellular potassium concentrations of ATR+ or ATR− cells prepared in buffer containing 0 or 50 mM K+ were determined. When assayed in buffer without potassium, cells were hyperpolarized, due to valinomycin-mediated potassium efflux. Cell hyperpolarization (negative inside) caused the uptake of positively charged di-S-C3 (5), resulting in quenched fluorescence. Conversely, cell depolarization was indicated by the increase in fluorescence after valinomycin addition. When [K+]o was equal to [K+]i, fluorescence was unchanged after valinomycin addition. The [K+]i values for cells prepared at a [K+]o of 50 mM were 50 and 25 mM for ATR+ and ATR− cells, respectively (data not shown). When the cells were prepared in buffer without potassium, the approximate [K+]i was accordingly smaller ([K+]i = 8 versus 4 mM for ATR+ and ATR−, respectively), but the twofold difference between them remained constant. Using equation 2 to convert differences in potassium concentrations into millivolts, a [K+]o value of 50 mM resulted in a Δψ of ∼0 mV for ATR+ cells and −18 mV for ATR− cells. Using equation 1 and the previously determined ΔpH values, the PMF was −18 mV for the ATR+ versus −59 mV for ATR− listeriae in medium containing 50 mM K+ (Table 1). For cells prepared in the absence of potassium, the Δψ in buffer with [K+]o at 50 mM was −47 and −65 mV for ATR+ and ATR− cells, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Bioenergetic parameters of ATR+ and ATR− cells prepared using buffers with two different potassium concentrationsa

| Cell preparation ([K+]o = 50 mM) | Calculated [K+]i (mM) | ΔpH (mV) (pHo = 5.5) | Δψ (mV) ([K+]o = 50 mM) | PMF (mV) (−) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATR+ | 50 | −18 | 0 | 18 |

| ATR− | 25 | −41 | −18 | 59 |

| ATR+ | 8 | −18b | −47 | 65 |

| ATR− | 4 | −41b | −65 | 106 |

Intracellular potassium concentrations ([K+]i) were estimated from changes in fluorescence using different extracellular potassium concentrations ([K+]o) in the presence of the ionophor valinomycin. Transmembrane pH (ΔpH) values were determined using a calibrated pH-sensitive fluorescent probe. Transmembrane electrical potentials (Δψ) were calculated using equation 2 for [K+]o = 50 mM. See the text for more details.

Assumes that [K+]o has a negligible affect on ΔpH.

(iii) Response of the transmembrane electric potential (Δψ) to nisin.

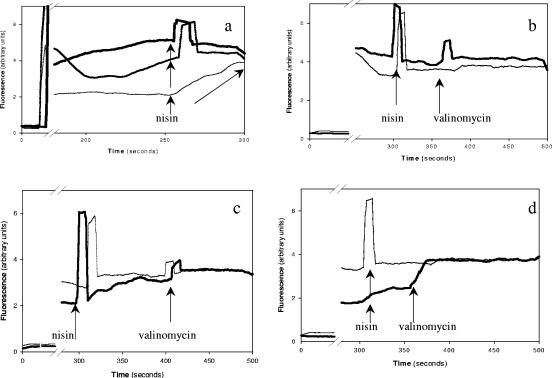

The data in Table 1 demonstrate that the ATR+ listeriae have both lower Δ pH and lower Δψ values than the ATR− listeriae. Since nisin action is enhanced by energized membranes, these results suggest that the lowered PMF of ATR+ L. monocytogenes made them less sensitive to nisin. To test this hypothesis, the Δψ of cells during exposure to nisin was initially studied with TSBYE acidified with lactic acid to pH 5.5 (ATR+) or with unacidified TSBYE at pH 7.0 (ATR−). Once the probe equilibrated in the system (200 s), the ATR+ cells had lower Δψ values than the ATR− cells. Nisin addition at 250 s depleted the Δψ of ATR− cells but not of ATR+ cells. Interestingly, when ATR− cells were assayed at pH 5.5, they behaved similarly to the ATR+ cells (Fig. 2a).

FIG. 2.

Fluorescence spectra used to assess Δψ of L. monocytogenes. In all cases, the fluorescent probe di-S-C3 (5) was added at ∼40 s and equilibrated with the cells after ∼200 s. Wide peaks coincident with reagent addition are artifacts from light entering the equipment during the addition. Data represent averages of two independent and reproducible spectra. (a) Assessment of Δψ of L. monocytogenes ATR+ cells at pH 5.5 (thick line) or ATR− cells at pH 5.5 (medium line) or 7.0 (thin line) suspended in 50 mM K+-HEPES-MES buffer containing 0.5% glucose. (b) Extended assessment of Δψ of live (thick line) and dead (control; thin line) ATR+ L. monocytogenes cells suspended in 50 mM K-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 5.5 containing 0.5% glucose. Neither nisin (50 μg ml−1; 300 s) nor valinomycin (added at ∼360 s) depleted the Δψ of the ATR+ cells. (c) Extended assessment of Δψ of live (thick line) and dead (thin line) ATR− L. monocytogenes suspended in 50 mM K+-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 7.0 containing 0.5% glucose. Nisin (50 μg ml−1; 300 s) rapidly depleted Δψ of the live ATR− cells, and valinomycin (400 s) depleted the residual Δψ. (d) Extended assessment of Δψ of ATR+ (thick line) L. monocytogenes suspended in 50 mM K+-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 7.0 containing 0.5% glucose. ATR+ cells had measurable Δψ values relative to those of the dead cell control (thin line). Nisin (50 μg ml−1; 300 s) rapidly depleted Δψ of the live ATR+ cells, and valinomycin (added at ∼360 s) depleted the residual Δψ.

To further support these observations, the Δψ values of ATR+ and ATR− cells were studied during longer periods (500 s) at pH 5.5 or 7.0 as they were treated with nisin, followed by valinomycin to deplete residual Δψ. After the probe equilibrated in the system (250 s) at pH 5.5, the Δψ values of live and dead ATR+ cells were similar and equal to zero (Fig. 2b). This confirmed our previous estimate using various extracellular potassium concentrations ([K+]o) and valinomycin. Neither nisin nor valinomycin addition increased fluorescence, indicating that neither depleted the Δψ. In contrast, ATR− cells assayed at their original pH of 7.0 had measurable Δψ values relative to the dead cell control (Fig. 2c). Nisin addition depleted the Δψ of ATR− cells to levels close to the dead cell control in ∼50 s. Subsequent addition of valinomycin further reduced Δψ to zero (Fig. 2c). This suggests that lactic acid, besides reducing the pHi, also reduced the Δψ of ATR− cells after 250 s, rendering them energetically resistant to nisin. Conversely, when ATR+ cells were assayed in buffer at pH 7.0, they had increased Δψ and therefore were energetically sensitized to nisin (Fig. 2d).

De novo protein synthesis and response to nisin.

Additional assays were conducted to investigate if the reduced Δψ of ATR− cells following exposure to pH 5.5 required de novo protein synthesis, a characteristic of the ATR. Such protein synthesis and therefore full ATR can be blocked if chloramphenicol is added no later than 10 min after exposure to mild acid (28). The Δψ decreased similarly in the presence or absence of chloramphenicol added at time zero (data not shown). This suggests that the changes in bioenergetics imposed by the acidified buffer and the resulting energetic protection to nisin were independent of de novo protein synthesis.

Determination of ATP levels.

Since the PMF can be interconverted with energy stored as ATP via the FoF1 ATPase complex, we examined the [ATP]i of cell preparations. Extracellular ATP levels were negligible compared to [ATP]i (data not shown), allowing total ATP determinations to be reported as intracellular ATP. For ATR+ cells, the [ATP]i of 7.64 ± 1.78 mM was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than that of ATR− cells (1.12 ± 1.38 mM) when tested immediately after induction. After treatment with 50 μg ml−1 nisin, the [ATP]i of the ATR+ cells decreased significantly to 0.29 ± 0.03 mM, a level similar to those of ATR− cells. These results were confirmed by kinetic experiments.

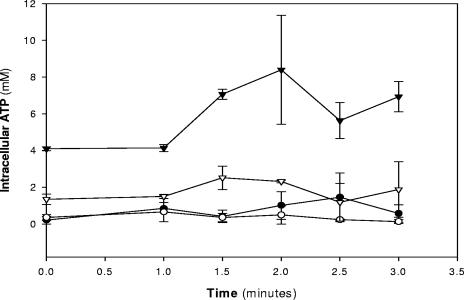

(i) Kinetics of ATP concentrations in the presence of glucose and nisin.

ATR+ and ATR− cells suspended in buffer at pH 5.5 were exposed to glucose or glucose and nisin. In the presence of glucose but absence of nisin, the ATR+ listeriae maintained higher [ATP]i relative to ATR− cells (Fig. 3). Nisin addition caused ATP depletion in both ATR+ and ATR− cells at time zero and significant ATP consumption despite the presence of glucose. When glucose was used alone, it did not alter ATP levels in either preparation. In addition, the presence of glucose did not counteract the ATP depletion caused by nisin.

FIG. 3.

Time-dependent intracellular ATP levels of ATR+ and ATR− listeriae during treatment with nisin and 0.5% glucose in 50 mM Na+-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 5.5. Data are averages of duplicate experiments, and error bars indicate 1 standard error.

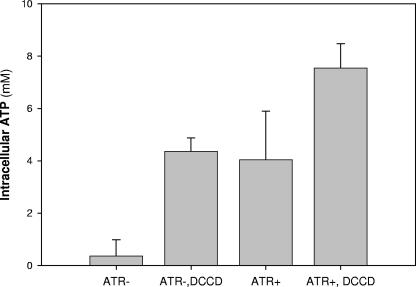

(ii) Role of the FoF1 ATPase complex on ATP levels.

For cells that were initially ATR−, induction of ATR in the presence of DCCD increased (P < 0.05) [ATP]i 12-fold (Fig. 4). The increase (1.8-fold) in ATR+ cells was statistically insignificant. This suggests that during ATR induction, the FoF1 ATPase was less active in ATR+ cells than in ATR− cells.

FIG. 4.

The intracellular ATP levels of listeriae after ATR induction in the absence or presence of 1 mM DCCD, prior to ATP determinations. ATR+ cells (closed symbols) and ATR− cells (open symbols) were suspended in 50 mM K+-HEPES-MES buffer at pH 5.5 and 7.0, respectively, in the presence of glucose (triangles) or glucose and nisin (circles). Data are averages of triplicate experiments, and error bars indicate 1 standard deviation.

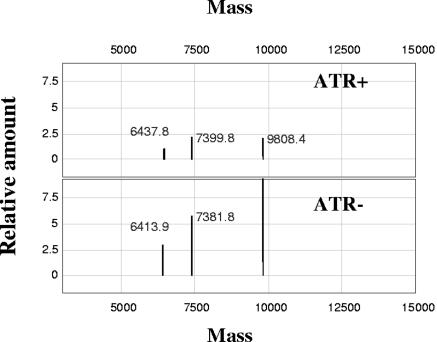

(iii) SELDI-TOF MS.

Average peak spectra (Fig. 5) revealed three hydrophobic proteins with altered abundance. The downregulated (P < 0.05) 7.4-kDa protein in ATR+ L. monocytogenes was of special interest, because the highly hydrophobic, proton-translocating, c subunit of the FoF1 ATPase complex of L. monocytogenes has a molecular mass of 7.2 kDa (17). Downregulation of the c subunit would be physiologically consistent with the high-ATP/low-PMF paradox and could explain the ATR-induced nisin resistance.

FIG. 5.

SELDI-TOF MS spectra obtained from lysates of ATR+ and ATR− Listeria monocytogenes cells. Vertical axes are relative intensities. Each of the two peak spectra below represents the average of three independent chip spots. See the text for details.

DISCUSSION

Bioenergetic changes, nisin resistance, and de novo protein synthesis.

ATR+ cells had low PMF and high intracellular ATP concentrations relative to ATR− cells. Reduction of pHi by lactic acid (Fig. 1) agrees with previous work (20, 23, 42), although when HCl is used as the acidulant, pHi can be maintained above 7 at pHo as low as 4 in the presence of glucose (34). Clearly, the nature of the acidulant and the availability of an energy source to drive proton pumping are important considerations. Nisin did not affect pHi, as similar trends were observed in the presence and absence of nisin. ATR+ cells also had lower Δψ values (close to 0 mV) than ATR− cells and did not respond energetically to nisin addition. However, immediately upon resuspension at neutral pH, their Δψ rapidly increased to the levels observed with ATR− cells, suggesting that the energetic conversion was independent of de novo protein synthesis. Moreover, ATR+ listeriae induced to a higher Δψ became energetically sensitized to nisin and valinomycin addition. Conversely, resuspension of ATR− in buffer at pH 5.5 immediately decreased their Δψ to levels similar to those observed with ATR+ cells, and as expected, rendering them energetically unresponsive to nisin and valinomycin.

To confirm that the bioenergetic changes were independent of de novo protein, experiments with ATR− cells using inhibitory levels of chloramphenicol from time zero were extended to 1,000 s. By excluding a role for de novo protein synthesis, we were able to focus on other early physiological events, including extended bioenergetic changes. When treated with nisin at 650 s and (subsequently) valinomycin, the ATR− cells had reduced Δψ values and therefore resistance to nisin and valinomycin, similar to that for the ATR+ cells. This also suggests that de novo protein synthesis was not involved in the bioenergetic changes.

The lisRK gene, a two-component signal transduction system in L. monocytogenes, is important in stress responses and in virulence regulation (7, 10) and has also been implicated in resistance to nisin and antibiotics using L. monocytogenes mutants (9). However, it has not been established whether lisRK is specifically upregulated during ATR induction. Even if it is, our results suggest that an earlier sequence of bioenergetic events prevents nisin action.

Increased ATP levels in ATR+ cells.

Immediately after ATR induction, the [ATP]i of the ATR-induced cells was significantly higher than for ATR− cells. This was a conceptual disconnect with the low PMF of the ATR+ cells. Since the L. monocytogenes genome lacks all the components required for a functioning respiratory electron transport chain (36), the FoF1 ATPase enzyme complex must function unidirectionally, building a PMF at the expense of energy from ATP hydrolysis. For control purposes, treatment with nisin strongly depleted ATP levels in both preparations; however, absolute comparisons were not possible because the different pH values of each preparation affected nisin's action (12). The ATP kinetic assays were performed with ATR+ and ATR− cells suspended in buffer at pH 5.5. The increased [ATP]i of ATR+ relative to ATR− cells persisted for the duration of the assay, suggesting that the 5-min exposure of ATR− cells to pH 5.5 did not induce an ATP-sparing mechanism. However, exposure to nisin depleted intracellular ATP from time zero, and the depletion was maintained for the duration of the experiment despite the presence of glucose. This indicates that ATR+ and ATR− cells instantly use their ATP reserves almost fully to survive exposure to nisin, underscoring the importance of ATP during nisin's action.

Decreased activity of FoF1 ATPase in ATR+ cells.

When DCCD was used to inhibit the FoF1 ATPase during ATR induction, the [ATP]i in ATR+ cells did not change. In contrast, the [ATP]i in ATR− listeriae increased significantly (P < 0.05) in the presence of DCCD, suggesting that their FoF1 ATPase but not the ATPase in ATR+ cells was consuming ATP to maintain their higher PMF values (Table 1). [ATP]i in the absence of DCCD did not differ significantly between ATR+ or ATR− cells assayed in K+- and Na+-HEPES-MES.

The apparent contradiction that nisin resistance can be accompanied by acid sensitivity in genetically altered mutants (24) or acid tolerance in physiologically adapted cells (2) may be reconciled through the role of the F0F1 ATPase, which is implicated in both phenotypes. The F0F1 ATPase complex has two main domains connected by a central stalk. The globular F1 ATPase domain is coupled to the membrane-spanning F0 proton-translocating domain (3). Certain chemicals and physiological conditions can uncouple ATP hydrolysis from proton pumping. This coupled or uncoupled state might explain how nisin-resistant cells can be acid resistant or generate an acid tolerance response.

Implication of the FoF1 ATPase c subunit.

SELDI-TOF MS using a hydrophobic chip allowed the use of total cell lysates and investigation of the highly hydrophobic c subunit of the FoF1 ATPase. In L. monocytogenes, the c subunit contains 72 amino acid residues and has a molecular mass of 7.2 kDa (17). Spectral analysis suggests that the 7.4-kDa signal (a 2.9% mass variation) was due to the c subunit of the enzyme. The signal was decreased in the ATR+ preparation (P < 0.05), indicating a reduction in the number of putative c subunits. The only other proteins identified in the L. monocytogenes genome which had a similar molecular weight were the cold shock proteins (17), but all of them are hydrophilic and would not be detected with a hydrophobic chip surface. Moreover, the downregulation of cold shock proteins during ATR induction has been excluded by others (1, 30, 40).

The c subunit of the FoF1 ATPase complex contains 9 to 14 subunits (41). The subunits are highly hydrophobic proteolipids and contain an Asp or Glu residue that supplies a proton-translocating carboxylate (18). The carboxylate and a conserved Arg residue of the a subunit apparently form a channel for proton transport. The FoF1 ATPase inhibitor DCCD specifically binds the proton-translocating carboxylate of the c subunit, inhibiting proton transport (18, 19). In L. monocytogenes, the c subunit lacks Asp, but side-chain carboxylates are located at Glu 56 and 39 (17).

In the mitochondrion and chloroplast, where the FoF1 ATPase operates in both directions, PMF positively regulates FoF1 ATPase across the internal membrane (35, 41). However, information on the regulation of L. monocytogenes FoF1 ATPase is scarce (8, 24). We propose that downregulation of the enzyme in ATR+ L. monocytogenes could be triggered by decreased PMF, avoiding the futile waste of ATP against overwhelming conditions established by the acid. This would save vital ATP during ATR induction, preparing the cell for survival under potentially lethal conditions.

Several investigators suggest that changes in the number of c subunits per enzyme complex alter the proton/ATP ratio (27, 33, 35, 41). In Escherichia coli, where the enzyme works in both the hydrolytic and synthetic directions, cells have more c subunits in their ATPase when growing in the presence of glucose than in the presence of succinate (27). In this way, metabolic requirements control the ATPase activity. ATR induction reduces the abundance of c subunits in listeriae, which decreases wasteful ATP consumption. This vital ATP sparing helps cell survival under lethal conditions. This novel link between the bioenergetics of the acid tolerance response and the proteome appears extensive and could contribute to the biological success of Listeria monocytogenes.

Acknowledgments

Research in our laboratory and preparation of the manuscript were supported by state appropriations, U.S. Hatch Act funds, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture CSRS NRI Food Safety Program (grant no. 99-35201-8611). M.B. is grateful for the financial support given by the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation-Embrapa.

We thank Richard Ludescher at Rutgers and Howard Shapiro at Harvard Medical School for their generous advice and enlightening discussions on fluorescence spectroscopic methods. We also appreciate the technical assistance provided by Shorab Sarker in the SELDI-TOF analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayles, D. O., B. A. Annous, and B. J. Wilkinson. 1996. Cold stress proteins induced in Listeria monocytogenes in response to temperature downshock and growth at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1116-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet, M., and T. J. Montville. 2005. Acid-tolerant Listeria monocytogenes persist in a model food system fermented with nisin-producing bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 40:237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyer, P. D. 1997. The ATP synthase—a splendid molecular machine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:717-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breukink, E., and B. de Kruijff. 1999. The lantibiotic nisin, a special case or not? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1462:223-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruno, M. E., A. Kaiser, and T. J. Montville. 1992. Depletion of proton motive force by nisin in Listeria monocytogenes cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2255-2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleveland, J., T. J. Montville, I. F. Nes, and M. L. Chikindas. 2001. Bacteriocins: safe, natural antimicrobials for food preservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 71:1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotter, P. D., N. Emerson, C. G. Gahan, and C. Hill. 1999. Identification and disruption of lisRK, a genetic locus encoding a two-component signal transduction system involved in stress tolerance and virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 181:6840-6843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter, P. D., C. G. Gahan, and C. Hill. 2000. Analysis of the role of the Listeria monocytogenes F0F1-ATPase operon in the acid tolerance response. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 60:137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotter, P. D., C. M. Guinane, and C. Hill. 2002. The LisRK signal transduction system determines the sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to nisin and cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2784-2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter, P. D., and C. Hill. 2003. Surviving the acid test: responses of gram-positive bacteria to low pH. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:429-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crandall, A. D., and T. J. Montville. 1998. Nisin resistance in Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 700302 is a complex phenotype. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:231-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vuyst, L., and E. J. Vandamme. 1994. Nisin, a lantibiotic produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis: properties, biosynthesis, fermentation and applications, p. 151-221. In L. De Vuyst and E. J. Vandamme (ed.), Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria. Chapman & Hall, New York, N.Y.

- 13.Ferreira, A., D. Sue, C. P. O'Byrne, and K. J. Boor. 2003. Role of Listeria monocytogenes σB in survival of lethal acidic conditions and in the acquired acid tolerance response. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2692-2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foegeding, P. M., A. B. Thomas, D. H. Pilkington, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1992. Enhanced control of Listeria monocytogenes by in situ-produced pediocin during dry fermented sausage production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:884-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.French, S. A., P. R. Territo, and R. S. Balaban. 1998. Correction for inner filter effects in turbid samples: fluorescence assays of mitochondrial NADH. Am. J. Physiol. 275:C900-C909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gahan, C. G., B. O'Driscoll, and C. Hill. 1996. Acid adaptation of Listeria monocytogenes can enhance survival in acidic foods and during milk fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3128-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couve, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Dominguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durant, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. Garcia-del Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gomez-Lopez, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueno, A. Maitournam, J. M. Vicente, E. Ng, H. Nedjari, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Perez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermolin, J., and R. H. Fillingame. 1989. H+-ATPase activity of Escherichia coli F1F0 is blocked after reaction of dicyclohexylcarbodiimide with a single proteolipid (subunit c) of the F0 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 264:3896-3903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoppe, J., H. U. Schairer, P. Friedl, and W. Sebald. 1982. An Asp-Asn substitution in the proteolipid subunit of the ATP-synthase from Escherichia coli leads to a non-functional proton channel. FEBS Lett. 145:21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ita, P. S., and R. H. Hutkins. 1990. Intracellular pH and survival of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A in tryptic soy broth containing acetic, lactic, citric, and hydrochloric acids. J. Food Prot. 54:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroll, R. G., and R. A. Patchett. 1992. Induced acid tolerance in Listeria monocytogenes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 14:224-227. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, J., M. L. Chikindas, R. D. Ludescher, and T. J. Montville. 2002. Temperature and surfactant induce membrane modifications that alter Listeria monocytogenes nisin sensitivity by different mechanisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5904-5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEntire, J. C. 2004. Relationship between nisin resistance and acid sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes. Ph.D. dissertation. The Graduate School, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick.

- 24.McEntire, J. C., G. M. Carman, and T. J. Montville. 2004. Increased ATPase activity is responsible for acid sensitivity of nisin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 700302. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2717-2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ming, X., and M. A. Daeschel. 1995. Correlation of cellular phospholipid content with nisin resistance of L. monocytogenes Scott A. J. Food Prot. 58:416-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montville, T. J., and M. E. Bruno. 1994. Evidence that dissipation of proton motive force is a common mechanism of action for bacteriocins and other antimicrobial proteins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 24:53-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller, V. 2003. Energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6345-6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Driscoll, B., C. G. Gahan, and C. Hill. 1996. Adaptive acid tolerance response in Listeria monocytogenes: isolation of an acid-tolerant mutant which demonstrates increased virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1693-1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Driscoll, B., C. G. M. Gahan, and C. Hill. 1997. Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of the acid tolerance response in Listeria monocytogenes LO28. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2679-2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phan-Thanh, L., and T. Gormon. 1995. Analysis of heat and cold shock proteins in Listeria by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 16:444-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phan-Thanh, L., F. Mahouin, and S. Alige. 2000. Acid responses of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 55:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romanova, N. A., L. Y. Brovko, L. Moore, E. Pometun, A. P. Savitsky, N. N. Ugarova, and M. W. Griffiths. 2003. Assessment of photodynamic destruction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes by using ATP bioluminescence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6393-6398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schemidt, R. A., J. Qu, J. R. Williams, and W. S. Brusilow. 1998. Effects of carbon source on expression of Fo genes and on the stoichiometry of the c subunit in the F1Fo ATPase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:3205-3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shabala, L., B. Budde, T. Ross, H. Siegumfeldt, M. Jakobsen, and T. McMeekin. 2002. Responses of Listeria monocytogenes to acid stress and glucose availability revealed by a novel combination of fluorescence microscopy and microelectrode ion-selective techniques. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1794-1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stock, D., A. G. Leslie, and J. E. Walker. 1999. Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science 286:1700-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stritzker, J., J. Janda, C. Schoen, M. Taupp, S. Pilgrim, I. Gentschev. P. Schreier, G. Geginat, and W. Goebel. 2004. Growth, virulence, and immunogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes aro mutants. Infect. Immun. 72:5622-5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swaminathan, B. 2001. Listeria monocytogenes, p. 383-409. In L. R. Beuchat, M. P. Doyle, and T. J. Montville (ed.), Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 38.van Schaik, W., C. G. Gahan, and C. Hill. 1999. Acid-adapted Listeria monocytogenes displays enhanced tolerance against the lantibiotics nisin and lacticin 3147. J. Food Prot. 62:536-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waggoner, A. S. 1979. Dye indicators of membrane potential. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 8:47-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wemekamp-Kamphuis, H. H., A. K. Karatzas, J. A. Wouters, and T. Abee. 2002. Enhanced levels of cold shock proteins in Listeria monocytogenes LO28 upon exposure to low temperature and high hydrostatic pressure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:456-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida, M., E. Muneyuki, and T. Hisabori. 2001. ATP synthase—a marvellous rotary engine of the cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:669-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young, K. M., and P. M. Foegeding. 1993. Acetic, lactic and citric acids and pH inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A and the effect on intracellular pH. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 74:515-520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]