Abstract

Quantitative Legionella PCRs targeting the 16S rRNA gene (specific for the genus Legionella) and the mip gene (specific for the species Legionella pneumophila) were applied to a total of 223 hot water system samples (131 in one laboratory and 92 in another laboratory) and 37 cooling tower samples (all in the same laboratory). The PCR results were compared with those of conventional culture. 16S rRNA gene PCR results were nonquantifiable for 2.8% of cooling tower samples and up to 39.1% of hot water system samples, and this was highly predictive of Legionella CFU counts below 250/liter. PCR cutoff values for identifying hot water system samples containing >103 CFU/liter legionellae were determined separately in each laboratory. The cutoffs differed widely between the laboratories and had sensitivities from 87.7 to 92.9% and specificities from 77.3 to 96.5%. The best specificity was obtained with mip PCR. PCR cutoffs could not be determined for cooling tower samples, as the results were highly variable and often high for culture-negative samples. Thus, quantitative Legionella PCR appears to be applicable to samples from hot water systems, but the positivity cutoff has to be determined in each laboratory.

Legionellosis generally carries a high mortality rate (15 to 20%) (12). It is acquired by inhalation or microaspiration of legionellae from contaminated environmental sources such as hot water systems and cooling towers (12). Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 is responsible for >80% of cases in most countries but for a lower percentage of cases (≈50%) in countries such as Australia and New Zealand (11, 28). Strain virulence, the presence of amoebae in the water, and immunosuppression are factors that are critical for the development of disease. The risk of legionellosis is theoretically influenced by the Legionella density in the water source (4, 16). Meenhorst et al. and Patterson et al. (18, 21) reported that densities above 104 to 105 CFU/liter represent a potential increased threat to human health. Several studies suggested that the proportion of sampling sites positive for Legionella is a better predictor of infection risk than colony counts (4, 16). National Legionella surveillance programs in France (9) and England (17) include regular monitoring of environmental samples.

Conventional culture is generally used to detect and count legionellae in water samples, but it can take up to 10 days to obtain a firm result. In addition, the sensitivity of culture is poor (10 to 30%) (2, 5), especially when samples also contain microorganisms that inhibit Legionella growth, and Legionella cells that are viable but nonculturable are not detected by conventional culture (13, 26) yet are potentially pathogenic (22). PCR is an alternative tool for rapid Legionella detection in environmental water. The detection rate of Legionella DNA by qualitative PCR is usually high, at >90% of positive samples (6, 19, 20), but PCR positivity offers little information on the relative risk of legionellosis. Quantitative real-time PCR gives the number of genome units (GU) per liter, but an equivalence with the number of CFU has not been established. Wellinghausen et al. (24) compared the results of the two techniques for 76 samples from three hot water systems and obtained a weak correlation (r2 = 0.32). The number of GU was usually higher than the number of CFU, probably owing to the presence of viable but nonculturable cells that are detected by PCR (26) but not by conventional culture (13).

For this study, we attempted to establish quantitative Legionella PCR cutoffs reflecting the risk of legionellosis according to the type of water sample. Conventional culture and quantitative Legionella PCR were compared with 223 samples from water distribution systems and 37 samples from cooling towers. Hot water system samples were shared between two different laboratories to evaluate cutoff variations according to experiment site.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and preparation of water samples.

Two studies were done in parallel in the French Rhône-Alpes area, one in Lyon and the other in Grenoble. For study 1, 131 1-liter hot water system samples and 37 cooling tower samples were collected in sterile bottles (CML, Nemours, France) between January and June 2005 by the French National Reference Center for Legionella, Lyon, and by CARSO-Laboratoire Santé Environnement Hygiène de Lyon (CARSO-LSEHL). For study 2, 92 1-liter hot water system samples were collected in sterile bottles (CML, Nemours, France) from a Grenoble hospital in 2004.

The samples were filtered through 0.45-μm polycarbonate filters (Millipore, St.-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France). The filters were then placed in 5 ml of sterile water and sonicated for 2 min (Fisher Bioblock Scientific, Illkirch, France) at 35 kHz. One milliliter of the resulting concentrate was stored at −20°C for PCR, and the remainder was used for culture.

Culture protocol.

Legionella species and serogroups were identified and counted according to the standard AFNOR NF T90-431 procedure (1). Before concentration, 200 μl of each hot water system sample and 200 μl of each cooling tower sample (undiluted and diluted 1/10) were directly plated on selective GVPC medium (Oxoïd, Wesel, Germany; AES, Combourg, France). One hundred microliters of the concentrate was plated on selective GVPC medium. Standard heat and acid treatments were used to eliminate contaminating organisms. Plates were incubated at 36 ± 2°C for 8 to 10 days, and colonies were counted at least three times (first at 3 or 4 days) until the end of incubation. Colonies with typical morphology were transferred to buffered charcoal-yeast extract medium (Oxoïd, Wesel, Germany; AES, Combourg, France) and control blood agar (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). Up to five colonies per sample (chosen for their heterogeneity and their time of appearance) were identified as Legionella pneumophila or non-Legionella pneumophila by using Legionella-specific latex reagents (Oxoid, Hampshire, England) and/or direct immunofluorescence with polyclonal rabbit sera (National Reference Center for Legionella, Lyon, France; Bio-Rad, Marne-la-Coquette, France).

Sample preparation for PCR.

Each stored 1-ml aliquot was thawed and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 10 min before decantation. The sediment was used for DNA extraction with a commercially available kit (High Pure PCR template preparation kit; Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). DNA was eluted in 50 μl of elution buffer (supplied in the kit) and stored at 4°C for up to 12 h before PCR. A negative control (purified PCR-grade water) was included in each batch of samples for DNA preparation and was measured by PCR to exclude contamination of the buffer solutions.

Cloning of internal inhibitor control.

To detect PCR inhibitors in the water samples, a 374-bp internal inhibitor control was cloned. It consisted of lambda DNA with terminal sequences complementary to both the 16S rRNA gene primers and the mip gene primers. Briefly, to generate the internal control, lambda DNA (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was amplified with the primers CIduoF (5′-CTC AGG GTT GAT AGG TTA AGA GCG CAT TGG TGC CGA TTT GGT ACG GAA AGC CGG TGG-3′) and CIduoR (5′-CTC CCA ACA GCT AGT TGA CAT CGG [CT]TT TGC CAT CAA ATC TTT CTG AAA GTC GAG TGC CTC ATT-3′) (Proligo, Paris, France) (underlined bases correspond to our Legionella-specific primers, and italic bases correspond to our Legionella pneumophila-specific primers). The resulting fragment was purified (QIAquick PCR purification kit; QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), cloned into the pDrive cloning vector, and transformed into Escherichia coli QIAGEN EZ by heat shock treatment, as recommended in the PCR cloning kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The correct clone was named CI Duo. Plasmid DNA was isolated with a QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and stored at −20°C until analysis.

Primers and probes.

The primers and probes used for 16S rRNA gene and mip PCRs have been described by Jonas et al. (14) (Table 1). For the quantitative genus-specific PCR assay, oligonucleotides amplified a 386-bp portion of the 16S rRNA gene, from base 451 to base 837, of Legionella pneumophila ATCC 33152. For Legionella pneumophila-specific PCR, the primers amplified a 186-bp fragment of the mip gene. Amplification was detected with a LightCycler DNA master hybridization probe kit (Roche) as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, two different oligonucleotide probes hybridize to a specific internal sequence of the amplicon. One probe is labeled at the 5′ end with the LightCycler Red 640 fluorophore, and the other probe is labeled at the 3′ end with fluorescein.

TABLE 1.

Primers and probes used for 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR

| Primer or probe function | Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA gene forward primer | 16S1-A | AGG GTT GAT AGG TTA AGA GC |

| 16S rRNA gene reverse primer | 16S2-A | CCA ACA GCT AGT TGA CAT CG |

| mip forward primer | mip1-A | GCA TTG GTG CCG ATT TGG |

| mip reverse primer | mip2-A | G[CT]T TTG CCA TCA AAT CTT TCT GAA |

| 16S rRNA gene forward probe | 16S1-S | AGT GGC GAA GGC GGC TAC CT-fluorescein |

| 16S rRNA gene reverse probe | 16S2-S | LC Red640-TAC TGA CAC TGA GGC ACG AAA GCG T |

| mip forward probe | mip1-S | CCA CTC ATA GCG TCT TGC ATG CCT TTA-fluorescein |

| mip reverse probe | mip2-S | LC Red 640-CCA TTG CTT CCG GAT TAA CAT CTA TGC C |

| CI Duo forward probe | C1-S | GGT GCC GTT CAC TTC CCG AAT AAC-fluorescein |

| CI Duo reverse probe | C2-S | LC Red 705-CGG ATA TTT TTG ATC TGA CCG AAG CG |

For specific detection of the internal control amplicon, one probe was labeled at the 5′ end with the LightCycler Red 705 fluorophore, and the other was labeled at the 3′ end with fluorescein. Due to labeling with the LightCycler Red 705 fluorophore instead of Red 640, the amplified products of the 16S rRNA or mip gene PCR and the lambda inhibitor control could be measured simultaneously by dual-color multiplex PCR and detected in different fluorescence channels (F2 and F3, respectively) of the LightCycler instrument.

The specificity of the mip primers for Legionella pneumophila has been reported by Cloud et al. (8). The specificity of the 16S rRNA gene primers for the genus Legionella has been checked by Wellinghausen et al. and by us in the present study: DNAs from the main Legionella strains found in the environment were amplified with the primers and probes used for 16S rRNA gene PCR (from 10 to 100 pg of bacterial DNA per PCR), whereas no amplification was observed with any non-Legionella strain tested (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Microorganisms tested for 16S rRNA gene PCR specificity

| Species and serogroupa | Origin or strain | Species and serogroupa | Origin or strain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legionella strains | Other bacterial strains | |||

| L. pneumophila | Acinetobacter junii | ATCC 17908 | ||

| 1 (Philadelphia 1) | ATCC 33152 | Acinetobacter baumanii | ATCC 19606 | |

| 2 (Togus 1) | ATCC 33154 | Acinetobacter lwoffii | ATCC 15309 | |

| 3 (Bloomington 2) | ATCC 33155 | Aeromonas caviae* | Environment | |

| 4 (Los Angeles 1) | ATCC 33156 | Aeromonas hydrophila* | Clinical isolate | |

| 5 | ATCC 33216 | Alcaligenes faecalis | Clinical isolate | |

| 6 (Chicago 2) | ATCC 33215 | Bacillus pumilus* | Clinical isolate | |

| 7 (Chicago 8) | ATCC 33823 | Bacillus subtilis* | Clinical isolate | |

| 8 | ATCC 35096 | Brevundimonas vesicularis | Clinical isolate | |

| 9 | ATCC 35289 | Burkholderia cepacia* | Clinical isolate | |

| 10 | ATCC 43283 | Chryseomonas luteola | Clinical isolate | |

| 11 | ATCC 43130 | Citrobacter freundii | ATCC 8090 | |

| 12 | ATCC 43290 | Citrobacter koseri | ATCC 27028 | |

| 13 | ATCC 43736 | Clostridium perfringens* | Clinical isolate | |

| 14 | ATCC 43703 | Enterobacter aerogenes | ATCC 13048 | |

| 15 | Environment | Enterobacter cloacae | Clinical isolate | |

| L. adelaidensis | ATCC 49625 | Enterococcus faecalis* | ATCC 29212 | |

| L. anisa | ATCC 35292 | Enterococcus faecium | Clinical isolate | |

| L. birminghamensis | ATCC 43702 | Escherichia coli | Clinical isolate | |

| L. bozemanii | ATCC 33217 | Flavobacterium indologenes* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. brunensis | ATCC 43878 | Haemophilus influenzae b* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. cherii | ATCC 35252 | Klebsiella oxytoca | ATCC 43863 | |

| L. cincinnatiensis | ATCC 43753 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Clinical isolate | |

| L. dumoffii | ATCC 33279 | Listeria monocytogenes* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. erythra | ATCC 35303 | Moraxella catarrhalis* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. feelei | ATCC 35849 | Mucor* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. gormanii | ATCC 33297 | Neisseria gonorrhoeae* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. gratiana | ATCC 49413 | Neisseria mucosa* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. hackeliae | ATCC 35250 | Pasteurella multocida* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. israelensis | ATCC 43119 | Proteus mirabilis | ATCC 29906 | |

| L. jamestownensis | ATCC 35298 | Proteus vulgaris | ATCC 29905 | |

| L. jordanis | ATCC 33623 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Clinical isolate | |

| L. lansingensis | ATCC 49751 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Clinical isolate | |

| L. longbeachae | ATCC 33462 | Pseudomonas putida | Clinical isolate | |

| L. maceachernii | ATCC 35300 | Salmonella enteritidis* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. micdadei | ATCC 33218 | Serratia marcescens | ATCC 13880 | |

| L. moravica | ATCC 43877 | Shigella sonnei* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. oakridgensis | ATCC 33761 | Sphingomonas paucimobilis | Clinical isolate | |

| L. parisiensis | ATCC 35299 | Staphylococcus aureus | Clinical isolate | |

| L. quinlivanii | ATCC 43830 | Staphylococcus epidermidis* | ATCC 1228 | |

| L. rubrilucens | ATCC 35304 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | ATCC 13637 | |

| L. sainthelensis | ATCC 35248 | Streptococcus agalactiae* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. spiritensis | ATCC 35249 | Streptococcus pneumoniae* | ATCC 49619 | |

| L. steigerwaltii | ATCC 35302 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Clinical isolate | |

| L. taurinensis* | Environment | Vibrio alginolyticus* | Clinical isolate | |

| L. tucsonensis | ATCC 49180 | Xanthomonas campestris* | Environment | |

| L. wadsworthii | ATCC 33877 |

*, strains investigated in this study. The other strains were previously investigated by Wellinghausen et al. (24).

PCR assay and amplification conditions.

The PCR mixtures for 16S rRNA and mip gene hybridization probe assays contained 5 μl of sample DNA, 1 μl (10 pmol) of primers 16S1-A/16S2-A or mip1-A/mip2-A, 0.8 μl (3,000 copies) of CI Duo, 2 μl (4 pmol) of probes 16S1-S/16S2-S or mip1-S/mip2-S, 1 μl (2 pmol) of probes C1-S/C2-S, 2.4 μl of MgCl2 (final concentration, 4 mM), 2 μl of master hybridization probe reaction mix (Roche), and PCR-grade sterile water to a final volume of 20 μl. Amplification and real-time quantification were carried out with a LightCycler instrument (Roche Diagnostics) under the following conditions: an initial 8-min denaturation step at 95°C followed by 45 cycles of repeated denaturation (10 s at 95°C), annealing (10 s at 57°C), and polymerization (15 s at 72°C). Each PCR protocol included a five- or six-point calibration scale (external standard), a negative extraction control (PCR-grade water), a positive control (Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1), and up to 12 water samples run in duplicate. Study 1 used a LightCycler 1.2 instrument, and study 2 used a LightCycler 2.0 instrument (the most recent version of the instrument).

The threshold cycle (CT), i.e., the cycle at which the sample fluorescence increases above a defined cutoff, is inversely proportional to the starting amount of nucleic acid. The threshold cycle for each standard was plotted against the log10 of the starting DNA quantity to generate a standard curve. The amplification efficiency (E) was estimated from the slope of the standard curve, as follows: E = 10−1/slope. A reaction with 100% efficiency generates a slope of −3.32 and has an efficiency of 2.

Preparation of external standard curves.

For external standards, Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 (ATCC 33152) was grown at 37°C on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar for 48 to 72 h before DNA extraction by the phenol-chloroform method. Genomic DNA was stored in sterile water before photometric assay. The number of copies of the Legionella genome in the initial purified DNA solution was calculated by assuming an average molecular mass of 660 Da for 1 bp of double-stranded DNA (PCR applications manual, 2nd ed., Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany, 1999) and using the following equation: number of copies = quantity of DNA (fg)/mean mass of the L. pneumophila genome. The mean mass of the L. pneumophila genome was calculated to be 3.7 fg from the mean size of the genome, which is assumed to be 3.4 Mb (7). This initial DNA solution was then divided into aliquots and stored at −20°C. For each LightCycler protocol, an aliquot was thawed and serially diluted to prepare five or six standard points containing 2 × 106 to 20 Legionella genome units per microliter (study 1) or 2.76 × 107 to 2.76 Legionella genome units per microliter (study 2). These solutions were stored at 4°C for up to 12 h. The standard curves were created by the second-derivative maximum method of the LightCycler software. Since, in contrast to the mip gene, the 16S rRNA gene exists in multiple copies per genome (25), different standard curves were used for the two PCRs.

Limits of detection and quantification of PCR assays.

The detection limit of each PCR assay (LDPCR) was defined as the smallest number of GU per assay which gave a positive result (amplification) in at least 90% of cases. The quantification limit (LQPCR) was defined as the smallest number of GU per assay yielding a coefficient of variation below 25%. For both determinations, 10 solutions at predefined LDPCR and LQPCR values were analyzed in duplicate. The global limits of detection and quantification of the method, LDmeth and LQmeth, respectively, expressed in GU/liter, were then obtained as follows: LDmeth = LDPCR/(f × F) = LDPCR × 50 and LQmeth = LQPCR/(f × F) = LQPCR × 50. F was the proportion of the concentrate used for DNA extraction (1/5, or 1 ml of 5 ml), and f was the proportion of DNA solution included in the PCR assay (1/10, or 5 μl of 50 μl).

Linearity of quantitative real-time Legionella PCR.

We prepared three independent series of serial dilutions of distilled water artificially contaminated by Legionella pneumophila ATCC 33152 (3 × 105, 3 × 104, 3 × 103, 3 × 102, and 30 CFU/liter). Each solution was treated and tested with the LightCycler 1.2 device for mip PCR, and the average of the PCR results was calculated and compared to the CFU values.

Statistical analysis.

LightCycler data were analyzed with LightCycler software (version 3.5 in study 1 and version 4.0 in study 2). For all comparisons based on mip PCR, we excluded samples in which non-L. pneumophila legionellae were detected by culture, as this PCR protocol was specific for the species L. pneumophila. Proportions were compared by using McNemar's exact test and Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

Limits of detection and quantification of PCR assays.

For study 1, the detection and quantification limits were estimated to be 5 and 100 GU/assay (250 and 5,000 GU/liter), respectively, for both the 16S rRNA gene and the mip gene. For study 2, the detection and quantification limits were lower than those for study 1: for 16S rRNA gene PCR, they were 0.6 GU/assay (30 GU/liter) and 10 GU/assay (500 GU/liter), respectively; for mip PCR, they were 6 GU/assay (300 GU/liter) and 20 GU/assay (1,000 GU/liter), respectively.

Linearity of quantitative real-time Legionella PCR.

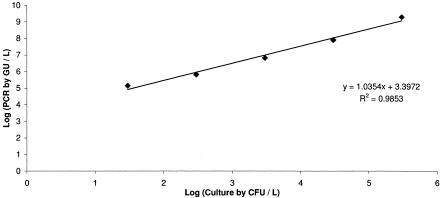

Legionella pneumophila quantification by mip PCR was linear from 30 to 3 × 105 CFU/liter (r2 = 0.99) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Linearity of quantitative Legionella mip PCR.

Qualitative and semiquantitative determinations of legionellae in water samples.

All culture and PCR results are available at the following website: www.lyon.inserm.fr/culture-PCR/table.pdf.

(i) Cooling tower samples (study 1).

PCR inhibition was observed with 1 (2.7%) of the 37 cooling tower samples. Among the remaining 36 samples, 9 (25%) were positive by culture, of which 8 (22.2%) had ≥250 CFU/liter of Legionella spp. Among these 36 samples, 36 (100%) were positive and 35 (97.2%) were quantifiable by 16S rRNA gene PCR. With mip PCR, among the 33 samples considered (3 samples yielding Legionella species other than L. pneumophila by culture were excluded), 31 (93.9%) were positive and 19 (57.6%) were quantifiable.

(ii) Hot water system samples (studies 1 and 2).

In study 1, PCR inhibition was observed with 3 (2.3%) of 131 samples. Among the remaining 128 samples, 55 (43%) were positive by culture, of which 27 (21.1%) had ≥250 CFU/liter of Legionella spp. Among these 128 samples, 117 (91.4%) were positive and 89 (69.5%) were quantifiable by 16S rRNA gene PCR. With mip PCR, among the 122 samples considered (6 samples yielding Legionella species other than L. pneumophila by culture were excluded), 94 (77%) were positive and 55 (45.1%) were quantifiable. In study 2, no PCR inhibition was observed. Among the 92 samples analyzed, 41 (44.6%) were positive by culture, of which 24 (26.1%) had ≥250 CFU/liter of Legionella spp. Among these 92 samples, 76 (82.6%) were positive and 56 (60.9%) were quantifiable by 16S rRNA gene PCR. With mip PCR, among the 91 samples considered (1 sample yielding a Legionella species other than L. pneumophila by culture was excluded), 57 (62.6%) were positive and 31 (34.1%) were quantifiable.

Whatever the study and the type of water sample, all 52 samples containing ≥250 CFU/liter legionellae were quantifiable by 16S rRNA gene PCR. In contrast, 7 (16.7%) of the 42 samples containing ≥250 CFU/liter L. pneumophila were not quantifiable by mip PCR. These seven samples contained 300 to 1,700 CFU/liter. The corresponding L. pneumophila culture isolates were separately amplified by mip PCR to rule out mip mutations.

Quantitative determination of legionellae in water samples.

For the following calculations, samples below the culture or PCR detection or quantification limit were attributed the cutoff value.

(i) Cooling tower samples (study 1).

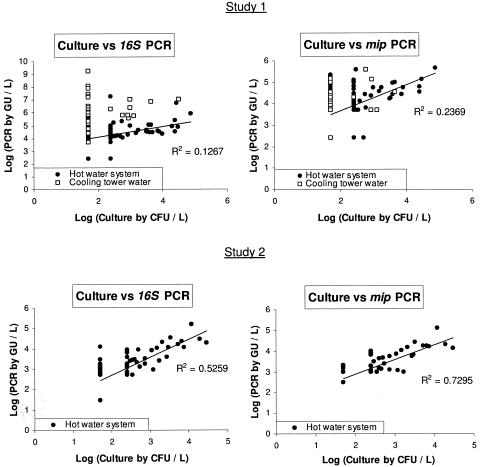

16S rRNA gene and mip PCR results were, on average, 49,000-fold and 110-fold higher than the culture results, respectively. No correlation was observed between these two methods, as the PCR results varied widely for a negative culture (from <5,000 to 1.8 × 109 GU/liter for 16S rRNA gene PCR and from <5,000 to 1.4 × 105 GU/liter for mip PCR) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of Legionella culture results with quantitative Legionella 16S rRNA gene PCR and mip PCR results for water samples analyzed at Lyon (study 1) and Grenoble (study 2). Samples below the detection or quantification limit by culture or PCR were attributed the cutoff value. For culture versus mip PCR comparisons, samples yielding non-L. pneumophila legionellae by culture were excluded.

(ii) Hot water system samples (studies 1 and 2).

In study 1, 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR results were, on average, 200-fold and 17-fold higher than the culture results, respectively; in study 2, 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR results were, on average, 5-fold and 4-fold higher than the culture results, respectively. A weak correlation between the PCR and culture results was observed in both studies. This correlation was slightly better in study 2 (r2 = 0.5259 and 0.7295 for 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR, respectively) than in study 1 (r2 = 0.1267 and 0.2369 for 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Classification of hot water system samples by use of PCR cutoff values.

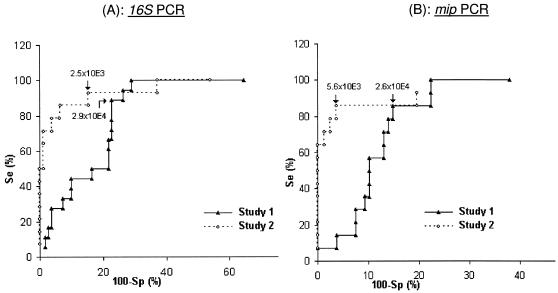

By using the receiver operating curve method (Fig. 3; Table 3), we defined PCR cutoff values for the detection of hot water system samples containing at least 103 CFU/liter legionellae, as follows.

FIG. 3.

Use of receiver operating curves to determine quantitative Legionella 16S rRNA gene PCR (A) and mip PCR (B) cutoff values (GU/liter) for identification of samples containing ≥103 CFU/liter legionellae among hot water system samples analyzed at Lyon (study 1) and Grenoble (study 2). For mip PCR (B), samples yielding non-L. pneumophila legionellae by culture (six samples in study 1 and one sample in study 2) were excluded. Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity.

TABLE 3.

Use of quantitative Legionella 16S rRNA gene PCR and mip PCR cutoff values for the classification of hot water system samples analyzed at Lyon (study 1) and Grenoble (study 2)

| Study and parameter | Value for 16S rRNA gene PCR | Agreement (%)a | Value for mip PCRb | Agreement (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| n | 128 | 128 | 122 | 122 | ||

| PCR cutoff value (GU/liter) | <2.9 × 104 | ≥2.9 × 104 | <2.6 × 104 | ≥2.6 × 104 | ||

| Samples with culture | ||||||

| <103 CFU/liter (n) | 85 | 25 | 78.9 | 94 | 14 | 86.9 |

| ≥103 CFU/liter (n) | 2 | 16 | 2 | 12 | ||

| 2 | ||||||

| n | 92 | 92 | 91 | 91 | ||

| PCR cutoff value (GU/liter) | <2.5 × 103 | ≥2.5 × 103 | <5.6 × 103 | ≥5.6 × 103 | ||

| Samples with culture | ||||||

| <103 CFU/liter (n) | 67 | 11 | 87.0 | 74 | 3 | 94.5 |

| ≥103 CFU/liter (n) | 1 | 13 | 2 | 12 | ||

The agreement represents the proportion of samples similarly classified by culture and PCR.

For mip PCR, samples yielding non-L. pneumophila legionellae by culture (six samples in study 1 and one sample in study 2) were excluded.

(i) 16S rRNA gene PCR.

A PCR cutoff of 2.9 × 104 GU/liter in study 1 correctly identified 16 (88.8%) of the 18 samples with ≥103 CFU/liter legionellae, with a specificity of 77.3%. In study 2, with a PCR cutoff of 2.5 × 103 GU/liter, 13 (92.9%) of the 14 samples with ≥103 CFU/liter legionellae were correctly identified, with a specificity of 84.6%. Under these conditions, the positive predictive value of PCR for samples containing ≥103 CFU/liter legionellae was 39% for study 1 and 54.2% for study 2; the negative predictive value of PCR for samples containing <103 CFU/liter legionellae was 97.7% for study 1 and 98.5% for study 2. The use of these PCR cutoffs correctly classified 101 (78.9%) of 128 samples in study 1 and 80 (87.0%) of 91 samples in study 2.

(ii) mip PCR.

A PCR cutoff of 2.6 × 104 GU/liter in study 1 correctly identified 12 (85.7%) of the 14 samples with ≥103 CFU/liter L. pneumophila, with a specificity of 87.0%. In study 2, a PCR cutoff of 5.6 × 103 GU/liter correctly identified 12 (85.7%) of the 14 samples with ≥103 CFU/liter L. pneumophila, with a specificity of 96.2%. Under these conditions, the positive predictive value of PCR for the selection of samples containing ≥103 CFU/liter L. pneumophila was 46.2% for study 1 and 80% for study 2. The negative predictive value of PCR for samples containing <103 CFU/liter L. pneumophila was 97.9% for study 1 and 97.4% for study 2. The use of these PCR cutoffs correctly classified 106 (86.9%) of the 122 samples in study 1 and 86 (94.5%) of the 91 samples in study 2.

Semiquantitative comparison of 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR values.

We compared the numerical results of the 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR assays for all the samples in which non-L. pneumophila Legionella species were detected by culture (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Semiquantitative comparison of 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR values for water samples analyzed at Lyon (study 1) and Grenoble (study 2)a

| Study | Water origin | Total no. of samples | 16S rRNA gene PCR > mip PCR (n) | mip PCR > 16S rRNA gene PCR (n) | McNemar's test P value (risk of 5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hot water system | 122 | 72 | 24 | <0.001 |

| Cooling tower | 33 | 32 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| 2 | Hot water system | 91 | 32 | 15 | 0.02 |

For both studies, samples yielding non-L. pneumophila legionellae by culture were excluded.

(i) Study 1.

Among the 122 hot water system samples, 72 had a 16S rRNA gene PCR value higher than the mip PCR value, whereas the reverse was observed for only 24 samples. Among the 33 cooling tower samples, 32 had a 16S rRNA gene PCR value higher than the mip PCR value, and the reverse was never observed. These differences were statistically significant in McNemar's test (P < 0.001). Fisher's exact test showed that the differences between the 16S rRNA gene and mip PCR results were significantly larger for the cooling tower samples (P < 0.001).

(ii) Study 2.

Among the 91 hot water system samples, 32 had a 16S rRNA gene PCR value higher than the mip PCR value, whereas the reverse was observed for 15 samples. This difference was statistically significant in McNemar's test (P = 0.02).

DISCUSSION

Wellinghausen et al. (24), using 16S rRNA gene PCR to quantify the genus Legionella and mip PCR to quantify L. pneumophila, found a weak correlation with conventional culture. In our two studies, with the first done in one laboratory with 131 hot water system samples and 37 cooling tower samples and the second done in another laboratory with 92 hot water system samples, we found that nonquantifiable 16S rRNA gene PCR was highly predictive of samples containing <250 CFU/liter legionellae. The proportions of nonquantifiable 16S rRNA gene PCR assays were low, at 30.5% and 39.1% of hot water system samples in studies 1 and 2, respectively, and 2.8% of cooling tower samples in study 1. We also found that PCR cutoff values accurately identified hot water system samples containing ≥103 CFU/liter legionellae (the first alert value in most European countries [9, 17]), with excellent sensitivities (from 87.7 to 92.9%) and good specificities (from 77.3 to 96.5%). The cutoffs had to be determined separately in each laboratory. No PCR cutoff could be defined for cooling tower samples, as the PCR results were highly variable and often very high even when conventional culture was negative.

We checked the linearity of quantitative Legionella PCR by adding L. pneumophila to sterile water (from 30 to 3 × 105 CFU/liter), widely covering the concentrations usually found in the environment (10, 24). Very good linearity was found with mip PCR (Fig. 1), and we extrapolated this result to 16S rRNA gene PCR. PCR inhibition occurred with up to 2.7% of our samples and was detected by amplification failure of our internal inhibitor control (CI Duo). We did not observed partial PCR inhibition, which would have been detected by an increased threshold cycle (CT) for the CI Duo sample.

We observed, as in other studies (24, 27), higher concentrations of legionellae by quantitative PCR than by conventional culture, both for hot water system and cooling tower samples (Fig. 2). This reflects the fact that PCR methods detect all legionellae (26), whereas culture only detects viable and culturable cells (13). Conventional culture probably underestimates the number of viable legionellae, owing to the use of selective media and pretreatment by acid or heating (13). Moreover, some Legionella strains could have more 16S rRNA gene copies than the reference strain ATCC 33152 used for the 16S rRNA gene PCR standard curve, leading to an overestimation of GU counts legionellae.

Whatever the type of water sample, a nonquantifiable PCR result was highly predictive of samples containing <250 CFU/liter legionellae. This was especially true for 16S rRNA gene PCR: all nonquantifiable samples contained <250 CFU/liter legionellae. mip PCR was less sensitive, as 7 of 42 water samples containing ≥250 CFU/liter L. pneumophila were not quantifiable. This lack of sensitivity could not be explained by mip mutations (corresponding L. pneumophila culture isolates were separately amplified by mip PCR) or by partial PCR inhibition. 16S rRNA gene PCR could thus be used as a first rapid screening method for samples containing <250 CFU/liter legionellae. Unfortunately, this selection will concern a minority of samples, as the proportions of nonquantifiable samples were low in our studies.

The main finding in this study is that the interpretation of a quantitative Legionella PCR assay depends largely on the type of water sample. With cooling tower samples, no correlation was observed between culture and PCR results, which were highly variable, often giving high GU counts for culture-negative samples (Fig. 2). Cooling towers are complex ecological systems (3), and the diversity of legionellae in the environment is extremely wide (15, 23). In our study 1, genomes of Legionella species other than L. pneumophila were much more frequently detected than L. pneumophila genomes in cooling tower samples (Table 4). Thus, a single quantitative PCR assay is of limited value for risk monitoring.

In contrast, with hot water system samples, we were able to define PCR cutoffs identifying samples containing >103 CFU/liter legionellae with excellent sensitivities and good specificities (Fig. 3). Using these PCR cutoffs, most samples were correctly classified by both 16S rRNA gene PCR (78.9% in study 1 and 87.0% in study 2) and mip PCR (86.9% in study 1 and 94.5% in study 2) (Table 3). Interestingly, the PCR cutoff values were significantly different (about 1 log) between the two participating laboratories, despite the use of the same DNA extraction and PCR protocols (except for the LightCycler version). This implies that each laboratory must determine its own cutoffs for the classification of hot water system samples. In the same way, hot water system samples containing ≥103 CFU/liter legionellae were more accurately identified in study 2 than in study 1, especially with mip PCR (94.5% agreement with culture versus 86.9% agreement in study 1 and a positive predictive value of 80% versus 46.2% in study 1). This result could probably also be explained by the samples investigated in the two studies. The hot water samples examined in study 1 were from several hot water systems, and in study 2 the samples were from one system only (a Grenoble hospital). This suggests that PCR results also depend on the composition of the matrix (water and its components).

It is not known whether water with a high PCR value but a relatively low (<103) CFU count is more infective than water with the same CFU count but a lower PCR value. This question makes sense if the role of amoebae is taken into consideration. The combination of a large number of legionellae inside amoebae (detected by PCR) and few planktonic bacteria in a water sample could explain the discrepancy between a low colony count and a high-level PCR result and could possibly predict a greater risk of infection compared to the situation with a similar colony count and PCR result.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to the staff of the Legionella National Reference Center, particularly Brigitte Aime and Caroline Bouveyron for their technical assistance. We thank René Ecochard (Department of Biostatistics, Université Claude-Bernard Lyon I) for statistical analysis, Marc Pawlowski (Roche Diagnostics) for LightCycler technical data, and David Young for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Association Française de Normalisation. 2003. Water quality—detection and enumeration of Legionella spp. and Legionella pneumophila. Method by direct inoculation and after concentration by membrane filtration of centrifugation. AFNOR NF T90-431 Septembre 2003. [Online.] http://www.boutique.afnor.fr/boutique.asp.

- 2.Ballard, A. L., N. K. Fry, L. Chan, S. B. Surman, J. V. Lee, T. G. Harrison, and K. J. Towner. 2000. Detection of Legionella pneumophila using a real-time PCR hybridization assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4215-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentham, R. H. 2000. Routine sampling and the control of Legionella spp. in cooling tower water systems. Curr. Microbiol. 41:271-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Best, M., V. L. Yu, J. Stout, A. Goetz, R. R. Muder, and F. Taylor. 1983. Legionellaceae in the hospital water-supply. Epidemiological link with disease and evaluation of a method for control of nosocomial Legionnaires' disease and Pittsburgh pneumonia. Lancet ii:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulanger, C. A., and P. H. Edelstein. 1995. Precision and accuracy of recovery of Legionella pneumophila from seeded tap water by filtration and centrifugation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1805-1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchbinder, S., K. Trebesius, and J. Heesemann. 2002. Evaluation of detection of Legionella spp. in water samples by fluorescence in situ hybridization, PCR amplification and bacterial culture. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien, M., I. Morozova, S. Shi, H. Sheng, J. Chen, S. M. Gomez, G. Asamani, K. Hill, J. Nuara, M. Feder, J. Rineer, J. J. Greenberg, V. Steshenko, S. H. Park, B. Zhao, E. Teplitskaya, J. R. Edwards, S. Pampou, A. Georghiou, I. C. Chou, W. Iannuccilli, M. E. Ulz, D. H. Kim, A. Geringer-Sameth, C. Goldsberry, P. Morozov, S. G. Fischer, G. Segal, X. Qu, A. Rzhetsky, P. Zhang, E. Cayanis, P. J. De Jong, J. Ju, S. Kalachikov, H. A. Shuman, and J. J. Russo. 2004. The genomic sequence of the accidental pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Science 305:1966-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cloud, J. L., K. C. Carroll, P. Pixton, M. Erali, and D. R. Hillyard. 2000. Detection of Legionella species in respiratory specimens using PCR with sequencing confirmation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1709-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conseil Supérieur d'Hygiène Publique de France. 2001. Le risque lié aux légionelles. Guide d’investigation et d’aide à la gestion. Rapport du Conseil Supérieur d'Hygiène Publique de France Juillet 2001. [Online.] http://www.sante.gouv.fr/htm/pointsur/legionellose/guid2005.pdf.

- 10.Delgado-Viscogliosi, P., T. Simonart, V. Parent, G. Marchand, M. Dobbelaere, E. Pierlot, V. Pierzo, F. Menard-Szczebara, E. Gaudard-Ferveur, K. Delabre, and J. M. Delattre. 2005. Rapid method for enumeration of viable Legionella pneumophila and other Legionella spp. in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4086-4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doleans, A., H. Aurell, M. Reyrolle, G. Lina, J. Freney, F. Vandenesch, J. Etienne, and S. Jarraud. 2004. Clinical and environmental distributions of Legionella strains in France are different. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:458-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fields, B. S., R. F. Benson, and R. E. Besser. 2002. Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:506-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussong, D., R. R. Colwell, M. O. O'Brien, E. Weiss, A. D. Pearson, R. M. Weiner, and W. D. Burge. 1987. Viable Legionella pneumophila not detectable by culture on agar media. Bio/Technology 5:947-950. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonas, D., A. Rosenbaum, S. Weyrich, and S. Bhakdi. 1995. Enzyme-linked immunoassay for detection of PCR-amplified DNA of legionellae in bronchoalveolar fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1247-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koide, M., A. Saito, N. Kusano, and F. Higa. 1993. Detection of Legionella spp. in cooling tower water by the polymerase chain reaction method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1943-1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kool, J. L., D. Bergmire-Sweat, J. C. Butler, E. W. Brown, D. J. Peabody, D. S. Massi, J. C. Carpenter, J. M. Pruckler, R. F. Benson, and B. S. Fields. 1999. Hospital characteristics associated with colonization of water systems by Legionella and risk of nosocomial Legionnaires' disease: a cohort study of 15 hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 20:798-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, J. V., and C. Joseph. 2002. Guidelines for investigating single cases of Legionnaires' disease. Commun. Dis. Public Health 5:157-162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meenhorst, P. L., A. L. Reingold, D. G. Groothuis, G. W. Gorman, H. W. Wilkinson, R. M. McKinney, J. C. Feeley, D. J. Brenner, and R. van Furth. 1985. Water-related nosocomial pneumonia caused by Legionella pneumophila serogroups 1 and 10. J. Infect. Dis. 152:356-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyamoto, H., H. Yamamoto, K. Arima, J. Fujii, K. Maruta, K. Izu, T. Shiomori, and S. Yoshida. 1997. Development of a new seminested PCR method for detection of Legionella species and its application to surveillance of legionellae in hospital cooling tower water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2489-2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng, D. L., B. B. Koh, L. Tay, and B. H. Heng. 1997. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction and conventional culture for the detection of legionellae in cooling tower waters in Singapore. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 24:214-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson, W. J., D. V. Seal, E. Curran, T. M. Sinclair, and J. C. McLuckie. 1994. Fatal nosocomial Legionnaires' disease: relevance of contamination of hospital water supply by temperature-dependent buoyancy-driven flow from spur pipes. Epidemiol. Infect. 112:513-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinert, M., L. Emody, R. Amann, and J. Hacker. 1997. Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2047-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turetgen, I., E. I. Sungur, and A. Cotuk. 2005. Enumeration of Legionella pneumophila in cooling tower water systems. Environ. Monit. Assess. 100:53-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wellinghausen, N., C. Frost, and R. Marre. 2001. Detection of legionellae in hospital water samples by quantitative real-time LightCycler PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3985-3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto, H., Y. Hashimoto, and T. Ezaki. 1993. Comparison of detection methods for Legionella species in environmental water by colony isolation, fluorescent antibody staining, and polymerase chain reaction. Microbiol. Immunol. 37:617-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto, H., Y. Hashimoto, and T. Ezaki. 1996. Study of nonculturable Legionella pneumophila cells during multiple-nutrient starvation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 20:149-154. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanez, M. A., C. Carrasco-Serrano, V. M. Barbera, and V. Catalan. 2005. Quantitative detection of Legionella pneumophila in water samples by immunomagnetic purification and real-time PCR amplification of the dotA gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3433-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu, V. L., J. F. Plouffe, M. C. Pastoris, J. E. Stout, M. Schousboe, A. Widmer, J. Summersgill, T. File, C. M. Heath, D. L. Paterson, and A. Chereshsky. 2002. Distribution of Legionella species and serogroups isolated by culture in patients with sporadic community-acquired legionellosis: an international collaborative survey. J. Infect. Dis. 186:127-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]