Abstract

A simple, effective method of unlabeled, stable gene insertion into bacterial chromosomes has been developed. This utilizes an insertion cassette consisting of an antibiotic resistance gene flanked by dif sites and regions homologous to the chromosomal target locus. dif is the recognition sequence for the native Xer site-specific recombinases responsible for chromosome and plasmid dimer resolution: XerC/XerD in Escherichia coli and RipX/CodV in Bacillus subtilis. Following integration of the insertion cassette into the chromosomal target locus by homologous recombination, these recombinases act to resolve the two directly repeated dif sites to a single site, thus excising the antibiotic resistance gene. Previous approaches have required the inclusion of exogenous site-specific recombinases or transposases in trans; our strategy demonstrates that this is unnecessary, since an effective recombination system is already present in bacteria. The high recombination frequency makes the inclusion of a counter-selectable marker gene unnecessary.

Antibiotic resistance or other selectable marker genes are routinely used to select for the chromosomal insertion of heterologous genes or the deletion of native genes by homologous recombination to create new strains of bacteria. The presence of antibiotic resistance genes in the host chromosome reduces the variety of plasmids that can be propagated in a cell, since these often rely on the same genes for their selection and maintenance. Genetically modified bacteria containing chromosomal antibiotic resistance genes are undesirable for biotherapeutic production, because the chromosomal DNA will represent a low-level contaminant of the final product and carry the risk of antibiotic resistance gene transfer to pathogenic bacteria in the patient or the environment. The insertion of a constitutively expressed marker gene can also alter the expression of adjacent chromosomal genes. Therefore, a rapid method of inserting genes into or deleting genes from bacterial chromosomes without leaving antibiotic resistance or other selectable marker genes behind is a significant advantage.

One strategy for unlabeled (i.e., without a selectable marker gene) chromosomal gene integration relies on inserting a plasmid via a single homologous recombination event, followed by the removal of the plasmid by a second recombination event (resolution) to hopefully produce the desired genotype (15, 17). A major disadvantage of this approach is that if the insertion or deletion reduces the fitness of the cell, the resolution event will predominantly regenerate the wild-type rather than the mutant genotype and therefore can be inefficient.

An alternative method is to insert an antibiotic resistance gene flanked by regions of chromosomal homology, where recognition sites for a site-specific recombinase (SSR) immediately flank the antibiotic resistance gene. Chromosomal integration strategies include traditional RecA-mediated homologous recombination and recombineering using PCR products and phage-encoded recombination functions, including ET cloning that utilizes RecE/RecT from bacteriophage Rac or bacteriophage λ Red recombination (7). Examples of SSRs/target sites used for antibiotic gene excision include Cre/loxP from bacteriophage P1 (14), Xis/attP from bacteriophage λ (30), and FLP/FRT (8) and R/RS (26) from the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, respectively. The recombination functions of transposons such as Tn4430 from Bacillus thuringiensis can also be employed (21). All these strategies require an exogenous recombinase or transposase to be expressed for use in a range of bacteria.

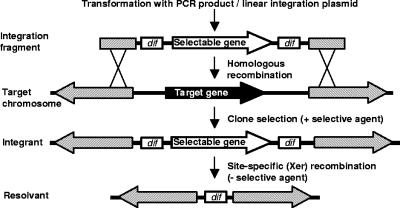

The method described here enlists the Xer recombinases that are naturally present in bacteria to excise antibiotic resistance genes following chromosomal integration, thereby eliminating the requirement for an exogenous SSR system. These are XerC and XerD in Escherichia coli (16), with homologues in many other species, such as RipX and CodV in Bacillus subtilis (22). The antibiotic resistance gene is flanked by the 28-bp dif sites, which enable Xer recombinases to resolve the chromosome and plasmid dimers generated by RecA in many prokaryotes that possess circular replicons. Therefore, intramolecular Xer recombination will excise a dif-flanked antibiotic resistance or other selectable marker gene from a chromosomally inserted cassette (Fig. 1). Here we demonstrate the use of this technology for antibiotic resistance gene removal by the deletion of chromosomal genes and the insertion of an exogenous gene. The frequency of gene excision by Xer recombination was also demonstrated in E. coli and B. subiltis.

FIG. 1.

Deletion of a target chromosomal gene and subsequent removal of the selectable marker (e.g., antibiotic resistance) gene by Xer recombination at flanking dif sites (Xer-cise). Shaded regions represent homology between the integration cassette and genes flanking the target gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA manipulation.

Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) was used to generate PCR products for cloning and gene insertion applications, and ReddyMix was used (Abgene) for screening of colonies by PCR, with standard PCR protocols employed for all reactions. Restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs), T4 DNA ligase, and the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega) were used according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Bacterial strains and media.

E. coli DH1 (11) and B. subtilis 168 (13) were the target strains for the gene integration experiments. E. coli and B. subtilis were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and Antibiotic Medium 3 (AM3; Difco), respectively, in liquid broth and 1.5% agar plates containing the following concentrations of antibiotics where required: 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin, 12 μg ml−1 tetracycline, or 20 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol (10 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol for B. subtilis). All bacterial cultures were incubated at 37°C, with shaking at 200 rpm for liquid cultures. Strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used directly in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH1 | F−supE44 hsdR17 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 endA1 thi-1 λ− | 11 |

| DH1M | DH1 msbB | This work |

| DH1R | DH1::rbpA | This work |

| B. subtilis | ||

| 168 | trpC2 | 13 |

| 168-mpr | trpC2 mpr | This work |

| 168-nprE | trpC2 nprE | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | Vector for cloning PCR products | Invitrogen |

| pKO3 | Source of cat in pTOPO-DifCAT | 17 |

| pTOPO-DifCAT | Precursor E. coli Xer-cise plasmid | This work |

| pQR163 | Source of rbpA | 27 |

| prbpA-DifCAT | Precursor rbpA integration Xer-cise plasmid | This work |

| pTP223 | Lambda Red helper plasmid | 18 |

| pypmP::CAT | Source of cat in pTOPO-bac.DifCAT | G. Homuth |

| pTOPO-bac.DifCAT | Precursor B. subtilis Xer-cise plasmid | This work |

| pmpr-DifCAT | mpr deletion Xer-cise plasmid | This work |

| pnprE-DifCAT | nprE deletion Xer-cise plasmid | This work |

Bacterial transformation.

Electrocompetent E. coli cells were produced by the method of Seidman et al. (23). Competent B. subtilis cells were produced by an optimized two-step method, which involved growth in a transformation medium containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, 2% glucose, 0.2% potassium l-glutamate, 11 mg liter−1 ammonium iron(III) citrate, 80 mg liter−1 l-tryptophan, 3 mM trisodium citrate, 3 mM MgSO4, and 0.1% casein hydrolysate. The culture was inoculated at an A500 of 0.1, grown to an A500 of 1.3, then diluted with an equal volume of transformation medium without casein hydrolysate, and incubated for 1 h. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in the supernatant at 1/8 of the culture volume, and resuspension buffer containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, 0.5% glucose, and 20 mM MgSO4 was added at 1/6 of the resuspended cell volume. DNA was added to 400-μl aliquots and incubated for 1 h; then an expression mixture containing 2.5% yeast extract, 2.5% casein hydrolysate, and 0.4 g liter−1 l-tryptophan was added, and the mixture was incubated for a further hour prior to plating on selective agar.

E. coli chromosomal gene integration.

The chloramphenicol resistance gene cat was amplified from plasmid pKO3 (17) using primers 5DifCAT and 3DifCAT. (All primers are described in Table 2.) These primers incorporated a 3′ region of homology flanking the cat gene in pKO3 with a 5′ tail that included a 28-bp E. coli dif site (difE. coli; GGTGCGCATAATGTATATTATGTTAAAT) and Bsu36I and NsiI restriction sites. This PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) to create a precursor gene deletion plasmid, pTOPO-DifCAT.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in this study

| Name | Size (nt) | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Function of PCR product |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5DifCAT | 81 | CCTTAGGATGCATGGTGCGCATAATGTATATTATGTTAAATCCCTTAT GCGACTCCTGCATCCCTTTCGTCTTCGAATAAA | difE. coli-cat-difE. coli for pTOPO-DifCAT |

| 3DifCAT | 81 | CCTTAGGATGCATATTTAACATAATATACATTATGCGCACCATCCGCTT ATTATCACTTATTCAGGCGTAGCACCAGGCGT | |

| 5bac.DifCAT | 84 | AATACCGGTGGTGACCACTTCCTAGAATATATATTATGTAAACTTATT CTTCAACTAAAGCACCCATTAGTTCAACAAACGAAA | difB. subtilis-cat-difB. subtilis for pTOPO.bac-DifCAT |

| 3bac.DifCAT | 77 | TTGAATATTAGTTTACATAATATATATTCTAGGAAGTGATATCTTCAAC TAACGGGGCAGGTTAGTGACATTAGAAA | |

| msb.int F | 70 | TGCGGCGAAAACGCCACATCCGGCCTACAGTTCAATGATAGTTCA ACAGAAGTGTGCTGGAATTCGCCCT | msbB deletion |

| msb.int R | 70 | TTGGTGCGGGGCAAGTTGCGCCGCTACACTATCACCAGATTGATT TTTGCATCTGCAGAATTCGCCCTTA | |

| Int F | 70 | AAACCCGCCCCTGACAGGCGGGAAGAACGGCAACTAAACTGTTAT TCAGTTTGCGCCGACATCATAACGG | rbpA insertion |

| Int R | 70 | GCCGGATGCGGCGTGAACGCCTTATCCGGTCTACCGATCCGGCAC CAATGGCTACGGTTTGATTAGGGAA | |

| SEQ5MPR | 20 | TGTTGAAGGATTGGAAAACG | mpr cloning locus |

| SEQ3MPR | 20 | ACTAATGGAATGGCATGATC | |

| YKTD | 21 | AATTAGAGACGTTAAGCTGGA | nprE cloning locus |

| SEQ3NPRE | 20 | ATACATAATGACTGAATAAC | |

| SML | 20 | TGACCTGGTGATTGTCACCC | msbB screening locus |

| SMR | 20 | TAAACCAGCAGGCCGTAAAC | |

| UbiB F | 20 | GATCGCCTGTTTGGCGATGC | ubiB-FadR screening locus |

| UbiB R | 20 | GAATCTGATGGAACGCAAAG | |

| C5MPR | 20 | TTTCGAATCAGAAATCACAC | mpr screening locus |

| C3MPR | 20 | CTACTCTTTCAGGCGCGCGG | |

| C5NPRE | 20 | TGATCAACCTCGAAAACCTG | nprE screening locus |

| C3NPRE | 20 | GTATATGGCATTACTGCACC |

For primers 5DifCAT and 3DifCAT, the difE. coli sites are double underlined and the cat homology regions are boldfaced. For primers 5bac.DifCAT and 3bac.DifCAT, the difB. subtilis sites are double underlined and the cat homology regions are boldfaced. For primers msb.int F and msb.int R, the homology regions flanking msbB are underlined and the pTOPO-DifCAT homology regions are boldfaced. For primers Int F and Int R, the homology regions flanking ubiB/fadR are underlined and the prbpA-DifCAT homology regions are boldfaced.

To delete msbB from the E. coli chromosome, the difE. coli-cat-difE. coli cassette from pTOPO-DifCAT was amplified by PCR using 70-nucleotide (nt) primers msb.int F and msb.int R (50 nt of the 5′ ends was homologous to the chromosomal regions flanking msbB, and 20 nt of the 3′ ends was homologous to pTOPO-DifCAT). DH1 was first transformed with the tetracycline-selectable plasmid pTP223, which provides the λ Red gene functions for protection and integration of linear DNA (18), Electrocompetent DH1(pTP223) was transformed with the difE. coli-cat-difE. coli PCR product, and integrants were selected on LB agar containing chloramphenicol. Subculturing in LB broth in the absence of antibiotics resulted in the loss of pTP223 and the generation of chloramphenicol-sensitive recombinant clones, which were identified by replica streaking onto agar plates with and without the selective antibiotic and screened by PCR using primers SML and SMR.

The rbpA gene from pQR163 (27) was cloned as an SphI-SmaI fragment adjacent to Bsu36I difE. coli-cat-difE. coli from pTOPO-DifCAT into prbpA-DifCAT. This was used as a PCR template with the 50-bp 5′ ends of the 70-nt primers Int F and Int R homologous to the ubiB-fadA target locus. The PCR integration fragment was transformed into electrocompetent DH1(pTP223) to create the integrant strain. Plasmid-free recombinant clones were selected as described above and screened by PCR using primers Ubi F and Ubi R.

B. subtilis chromosomal gene integration.

The chloramphenicol resistance gene cat was amplified from plasmid pypmP::CAT using primers 5bac.DifCAT and 3bac.DifCAT. These primers incorporated a 3′ region of homology flanking the cat gene and a 5′ tail that included a 28-bp B. subtilis dif site (difB. subtilis; ACTTCCTAGAATATATATTATGTAAACT) and the AgeI and BstEII restriction sites. This PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to create a precursor gene deletion plasmid, pTOPO-bac.DifCAT.

For deletion of the majority of the cistrons of extracellular protease genes mpr and nprE from B. subtilis 168, these genes were amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA including ∼0.4 kb of homology flanking the regions to be deleted (using primer sets SEQ5MPR-SEQ3MPR and YKTD-SEQ3NPRE) and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to create pTOPO-mpr and pTOPO-nprE. mpr was removed by AgeI-SspI digestion and replaced with an AgeI-BfrBI difB. subtilis-cat-difB. subtilis fragment from pTOPO-bac.DifCAT to create deletion plasmid pmpr-DifCAT. nprE was removed by BstEIII-SspI digestion and replaced with a BstEII-BfrBI difB. subtilis-cat-difB. subtilis fragment from pTOPO-bac.DifCAT to create deletion plasmid pnprE-DifCAT. The deletion plasmids were linearized by restriction digestion in the cloning vector and transformed into competent B. subtilis 168, and integrants were selected on AM3 agar containing 10 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol. Subculturing in AM3 broth in the absence of antibiotics produced chloramphenicol-sensitive recombinant clones, identified by replica plating onto agar with and without the selective antibiotic. Putative recombinants were screened by PCR using primer set C5MPR-C3MPR or C5NPRE-C3NPRE, which flanked the deletion sites.

Estimation of excision frequency at dif sites.

Triplicate cultures of integrant strains containing chloramphenicol were used to inoculate 50-ml shake flasks without chloramphenicol to a starting A600 of 0.005. After each 24-h period, the number of generations reached was calculated and the cultures inoculated into fresh medium. Following further rounds of daily subculturing (total growth times, 48 and 96 h for E. coli and 24 and 48 h for the B. subtilis strains), the total number of generations throughout the experiment was calculated, and cultures were serially diluted and plated onto nutrient agar to give single colonies. One hundred colonies derived from each culture were plated onto fresh nutrient agar with or without chloramphenicol. Clones that had become chloramphenicol sensitive were screened by PCR using diagnostic primers listed in Table 2. The resulting data were used to calculate the excision frequencies.

RESULTS

Gene integration and selectable marker excision.

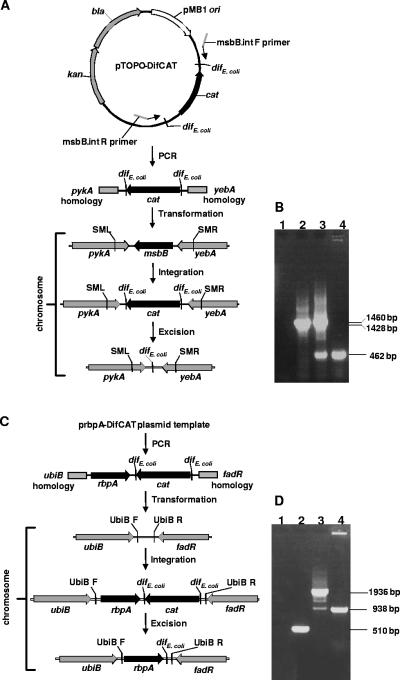

The msbB gene product attaches the immunogenic myristoyl group to lipid A in the cell membrane (25), so msbB was deleted from the E. coli DH1 chromosome to generate a new strain with reduced endotoxin activity suitable for plasmid DNA production (Fig. 2A). A plasmid with the cat gene flanked by dif sites, pTOPO-DifCAT, was used as a template for assembling a deletion cassette by PCR using primers with 5′ homology to the target locus flanking the region to be deleted. PCR screening using primers SML and SMR to amplify a part of the msbB locus (Fig. 2B) gave a product of 1,428 bp for the native msbB locus of DH1 (lane 2). The integrant locus was 1,460 bp, but this PCR also amplified a product of 462 bp, indicating an msbB deletion, as a proportion of the population underwent Xer recombination even in the presence of chloramphenicol (lane 3). This could be occurring in the later stages of growth as the antibiotic is degraded and the selection pressure reduced. The PCR of the recombinant, msbB-deleted strain DH1M, shows only the 462-bp deletion product (lane 4).

FIG. 2.

Integration of PCR products and antibiotic resistance gene excision in E. coli. (A) Deletion of msbB using a PCR product with homology to the regions flanking chromosomal msbB to generate DH1M. (B) Agarose gel of PCR products generated using primers SML and SMR. Lane 1, negative control (no template DNA); lane 2, wild-type msbB locus; lane 3, integrant; lane 4, deletion mutant. (C) Chromosomal insertion of rbpA using a PCR product with homology to the ubiB-fadR intergenic region to generate DH1R. (D) Agarose gel of PCR products generated using primers UbiB F and UbiB R. Lane 1, negative control (no template DNA); lane 2, wild-type ubiB-fadR locus; lane 3, integrant; lane 4, recombinant with inserted rbpA.

The bovine pancreatic RNase gene rbpA was inserted into a chromosomal space between two native genes (ubiB and fadA) in E. coli DH1 that had been chosen arbitrarily (Fig. 2C). This insertion created DH1R, a recA equivalent of a previous strain, JMRNaseA (4), that exports RNase A to the periplasm, where it folds to the active conformation and is then released to degrade RNA upon cell lysis. PCR using primers UbiB F and UbiB R, flanking the integration region in DH1, gave a product of 510 bp for the native ubiB-fadA locus (Fig. 2D, lane 2). The integrant locus gave 1,936 bp, but this PCR also amplified a product of 938 bp, indicating deletion of cat, as a proportion of the population underwent Xer recombination even in the presence of chloramphenicol (lane 3). The integrated rbpA gene without cat was detected as a 938-bp PCR product in DH1R (lane 4).

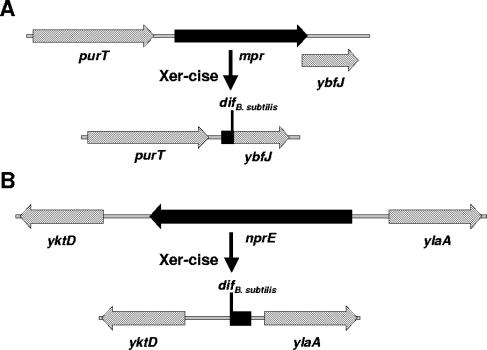

B. subtilis secretes proteases into the growth medium, and these can have the adverse effect of degrading secreted recombinant proteins. Two of these extracellular protease genes, mpr (24) and nprE (28), were chosen to test dif-flanked selectable marker gene deletion. The PCR results were equivalent to those seen for E. coli and so are not shown; as with E. coli, the integrant strains cultured in the presence of chloramphenicol also displayed the recombinant PCR products. Diagrams of the extracellular protease gene loci in wild-type B. subtilis 168 and the deleted loci in 168-mpr and 168-nprE are shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Wild-type and deleted loci of extracellular protease genes mpr (A) and nprE (B) in B. subtilis.

Excision frequency at dif sites.

The percentages of integrant cells that had undergone Xer recombination to excise the chromosomal cat gene at selected time points are given in Table 3. Results were determined by subculturing for a time sufficient to identify a recombinant clone if 100 colonies were replica plated in the presence or absence of the selective antibiotic. With E. coli, this time was 48 h after inoculation, but with the significantly higher frequency of Xer recombination in B. subtilis, a high proportion of cells had resolved after 24 h. All chloramphenicol-sensitive colonies were screened by PCR to ensure that this phenotype was due to cat excision and not to mutation.

TABLE 3.

Gene excision frequencies by Xer site-specific recombination at dif sites

| Parameter | Value for the following locus at the indicated time (h):

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli msbB

|

E. coli ubiB-fadA

|

B. subtilis mpr

|

B. subtilis nprE

|

|||||

| 48 | 96 | 48 | 96 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | |

| No. of generationsa,b | 19.7 ± 0.1 | 39.2 ± 0.1 | 18.7 ± 0.2 | 37.9 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.1 | 15.4 ± 1.4 | 8.4 ± 0.1 | 15.8 ± 1.3 |

| % Recombinantsb,c | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 7.7 ± 2.3 | 1.0 | 4.6 ± 3.2 | 41.3 ± 4.7 | 68.7 ± 8.1 | 22.0 ± 2.6 | 48.3 ± 4.5 |

| Excision frequencyd | 3.2 × 10−3 | 2.0 × 10−3 | 5.3 × 10−4 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

Calculated as (lnNt − lnN0)/ln2 where Nt is the final optical density and N0 is the optical density of the inoculum (absorbance at 600 nm) at each 24-h subculture point.

Results are means and standard deviations for simultaneous experiments on three integrant clones.

The percentage of cells within the population that have undergone a recombination event to excise the cat gene.

The proportion of recombinants per generation (percentage of recombinants/100 × number of generations).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated a simple, rapid technique for selectable marker gene removal following gene integration in bacteria that should be applicable to all prokaryotes with the ubiquitous Xer dimer resolution system (20). A cassette consisting of an antibiotic resistance gene flanked by dif sites and regions of homology to the chromosomal target is amplified by PCR or cloned into a plasmid and then integrated into the chromosome. Cells that have undergone intramolecular Xer recombination at dif sites during further culture (and therefore have lost the resistance gene) are identified by antibiotic sensitivity and verified by PCR. We propose the term “Xer-cise” to describe this technique.

With unlabeled gene replacement technologies that rely on homologous rather than site-specific recombination for removal of the integrated cassette, a gene that allows positive selection is required (usually adjacent to the antibiotic resistance gene), since the homologous recombination frequency is too low to make screening by replica plating a viable method of identifying recombinant clones. An example is sacB, which expresses the B. subtilis enzyme levansucrase. This enzyme converts sucrose into levans, which are lethal to E. coli (17). If an integrant that has been cultured in the absence of the selective antibiotic is plated on a medium containing sucrose, any cell that has not lost both genes (by a second homologous recombination event) will be killed. A counter-selectable marker gene used in B. subtilis to identify recombinants is the upp gene encoding uracil phosphoribosyltransferase, which is toxic on media containing 5-fluorouracil, but upp must be deleted from the chromosome before this system can be used (10). The frequency of Xer recombination is high enough to detect recombinant clones by replica plating a small number of colonies onto agar plates with and without the selective antibiotic, making the inclusion of a counter-selectable gene unnecessary. This is advantageous, since certain counter-selectable genes such as sacB can be mildly toxic even when counter-selection is not present, leading to an accumulation of cells carrying mutations in sacB and therefore generating false-positive results during clone selection.

Because recombination frequency is independent of the presence of a selective antibiotic, integrant cells will undergo Xer recombination even if the antibiotic is present (Fig. 2, lanes 3), but the resulting recombinants will be killed. We do not report analyses of the modified phenotypes of the recombinant strains here, because we are focusing on gene integration and excision, but in addition to the diagnostic PCRs, the chromosomal insertion sites of recombinant clones were sequenced, confirming that a single dif site had been generated.

The natural dif site is in the chromosome terminus region and is essential for correct chromosome segregation at cell division: deletion of difE. coli results in a subpopulation of E. coli cells with a filamentous morphology (12). However, if natural difE. coli is deleted, another difE. coli site will not enable dimer resolution if placed outside of the ∼30-kb dif activity zone (DAZ) in the terminus region (6, 16). Therefore, while our method involves insertion of one or more extra dif sites at different chromosomal loci, this should not have an adverse effect on chromosome segregation, although the possibility that introduction of multiple dif sites in close proximity might result in deletion of intervening chromosomal DNA should be considered.

The efficiency of Xer recombination at tandemly repeated dif sites within the E. coli DAZ has been determined by Barre et al. (1) using a difE. coli-flanked kanamycin resistance gene, and more than 90% of cells of a RecA− strain became kanamycin sensitive following overnight culture (99% for a RecA+ strain). This is a significantly higher percentage than we have observed in our RecA− examples outside of the DAZ (1.0 and 6.3% after 48 h). However, the frequencies that we report still allow the required recombinant mutants to be easily identified by screening a small number of colonies for antibiotic sensitivity and may be higher in a RecA+ strain. The recombination frequency in B. subtilis is significantly higher than that in E. coli, suggesting that intramolecular recombination by RipX/CodV is more efficient than that by XerC/XerD, although the examples presented here compare RecA− E. coli and RecA+ B. subtilis strains. The deleted B. subtilis protease genes were not in a region equivalent to the DAZ, and the dif-flanked antibiotic resistance genes were of equivalent lengths in E. coli and B. subtilis integration plasmids, so these factors cannot be responsible for the differences in Xer recombination frequency between the two species. The Xer recombination frequency per generation (Table 3, Excision frequency) remained constant in all examples except for E. coli ubiB-fadA, indicating that repeated subculturing should increase the probability of identifying a recombinant.

It should be noted that although dif-containing plasmids can be integrated into the chromosomal dif site (19), this is a different approach in which the entire plasmid is integrated by Xer recombination and excised by the same mechanism, so the plasmid is unstable in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure.

We have used chromosomal dif sites as the substrates for intramolecular Xer recombination, but the equivalent plasmid dimer resolution sites, such as the cer or psi sites or hybrids thereof that function in E. coli, may also be suitable. These require accessory sequences for recombination on plasmids but not for chromosomal recombination (5). Intramolecular recombination will occur between two dif sites on plasmids (2, 19), but culturing in a medium containing chloramphenicol prevented this from being a problem with our precursor plasmids. However, excision of plasmid-borne genes is an alternative application of Xer-cise and may be used to regulate gene expression or excise antibiotic resistance genes when used with antibiotic-free plasmid maintenance systems.

We have used PCR primers containing 50-bp regions of homology to the chromosomal target for λ Red integration, since short homologous sequences are known to work well in E. coli (8). For B. subtilis we used linearized plasmids with inserts containing approximately 400 bp of target locus homology, but we have not yet attempted to use homology regions of a size that can be synthesized as primers. Splicing PCR can also be used to assemble integration cassettes with long regions of homology as an alternative to plasmid construction. The λ Red functions encoded on pTP223 were used to enable insertion of linear fragments in E. coli, since Gam inhibits linear DNA degradation by the native RecBCD exonuclease, while Beta and Exo enable chromosomal integration (18), essential in RecA− strains. For alternative integration methods, ET recombination utilizing RecE and RecT could be used in sbcA E. coli strains (29), or it may be possible to use electroporation for chromosomal integration of linear DNA without the need for λ Gam (9). With B. subtilis, no additional functions are required in trans to mediate homologous recombination, since it does not significantly degrade linear DNA following transformation.

We anticipate that the Xer-cise technique of selectable marker gene excision at dif sites will simplify and accelerate the production of unlabeled mutants in E. coli and B. subtilis and will be applicable to the ever-increasing number of bacteria for which the native dif site has been elucidated (3). It should also be possible to use the Xer recombinase genes in trans to enable selectable marker gene removal in eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Sherratt for background information and enlightening technical discussions, Colin Harwood for expert advice on Bacillus subtilis, Kenan Murphy for providing pTP223, and Georg Homuth for pypmP:CAT.

This work was partly supported by a LINK Applied Genomics Programme grant from the United Kingdom Department of Trade and Industry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barre, F.-X., M. Aroyo, S. D. Colloms, A. Helfrich, F. Cornet, and D. J. Sherratt. 2000. FtsK functions in the processing of a Holliday junction intermediate during bacterial chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 14:2976-2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blakely, G. W., and D. J. Sherratt. 1994. Interactions of the site-specific recombinases XerC and XerD with the recombination site dif. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:5613-5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalker, A. F., A. Lupas, K. Ingraham, C. Y. So, R. D. Lunsford, T. Li, A. Bryant, D. J. Holmes, A. Marra, S. C. Pearson, J. Ray, M. K. Burnham, L. M. Palmer, S. Biswas, and M. Zalacain. 2000. Genetic characterisation of Gram-positive homologs of the XerCD site-specific recombinases. J. Mol. Biotechnol. 2:225-233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooke, G. D., R. M. Cranenburgh, J. A. J. Hanak, P. Dunnill, D. R. Thatcher, and J. M. Ward. 2001. Purification of essentially RNA free plasmid DNA using a modified Escherichia coli host strain expressing ribonuclease A. J. Biotechnol. 85:297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornet, F., I. Mortier, J. Patte, and J.-M. Louarn. 1994. Plasmid pSC101 harbors a recombination site, psi, which is able to resolve plasmid multimers and to substitute for the analogous chromosomal Escherichia coli site dif. J. Bacteriol. 176:3188-3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornet, F., I. Mortier, J. Patte, and J.-M. Louarn. 1996. Restriction of the activity of the recombination site dif to a small zone of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Genes Dev. 10:1152-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Court, D. L., J. A. Sawitzke, and L. C. Thomason. 2002. Genetic engineering using homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36:361-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Karoui, M., S. K. Amundsen, P. Dabert, and A. Gruss. 1999. Gene replacement with linear DNA in electroporated wild-type Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:1296-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabret, C., S. D. Ehrlich, and P. Noirot. 2002. A new mutation delivery system for genome-scale approaches in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 46:25-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuempel, P. L., J. M. Henson, L. Dircks, M. Tecklenburg, and D. F. Lim. 1991. dif, a recA-independent recombination site in the terminus region of the chromosome of Escherichia coli. New Biol. 3:799-811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Borgne, S., F. Bolivar, and G. Gosset. 2004. Plasmid vectors for marker-free chromosomal insertion of genetic material in Escherichia coli. Methods Mol. Biol. 267:135-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leenhouts, K., G. Buist, A. Bolhuis, A. ten Berge, J. Kiel, I. Mierau, M. Dabrowska, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1996. A general system for generating unlabelled gene replacements in bacterial chromosomes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 253:217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leslie, N. R., and D. J. Sherratt. 1995. Site-specific recombination in the replication terminus region of Escherichia coli: functional replacement of dif. EMBO J. 14:1561-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Link, A. J., D. Phillips, and G. M. Church. 1997. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J. Bacteriol. 179:6228-6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy, K. C. 1998. Use of bacteriophage λ recombination functions to promote gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:2063-2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recchia, G. D., M. Aroyo, D. Wolf, G. Blakely, and D. J. Sherratt. 1999. FtsK-dependent and -independent pathways of Xer site-specific recombination. EMBO J. 18:5724-5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Recchia, G. D., and D. J. Sherratt. 1999. Conservation of xer site-specific recombination genes in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 34:1146-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchis, V., H. Agaisse, J. Chaufaux, and D. Lereclus. 1997. A recombinase-mediated system for elimination of antibiotic resistance gene markers from genetically engineered Bacillus thuringiensis strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:779-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sciochetti, S. A., P. J. Piggot, and G. W. Blakely. 2001. Identification and characterisation of the dif site from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:1058-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seidman, C. E., K. Struhl, J. Sheen, and T. Jessen. 1997. High-efficiency transformation by electroporation, p. 1.8.4-1.8.5. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 24.Sloma, A., C. F. Rudolph, G. A. Rufo, Jr., B. J. Sullivan, K. A. Theriault, D. Ally, and J. Pero. 1990. Gene encoding a novel extracellular metalloprotease in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 172:1024-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Somerville, J. E., L. Cassiano, B. Bainbridge, M. D. Cunningham, and R. P. Darveau. 1995. A novel Escherichia coli lipid A mutant that produces an antiinflammatory lipopolysaccharide. J. Clin. Investig. 97:359-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugita, K., T. Kasahara, E. Matsunaga, and H. Ebinuma. 2000. A transformation vector for the production of marker-free transgenic plants containing a single copy transgene at high frequency. Plant J. 22:461-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarragona-Fiol, A., C. J. Taylorson, J. M. Ward, and B. R. Rabin. 1992. Production of mature bovine pancreatic ribonuclease in Escherichia coli. Gene 118:239-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang, M. Y., E. Ferrari, and D. J. Henner. 1984. Cloning of the neutral protease gene of Bacillus subtilis and the use of the cloned gene to create an in vitro-derived deletion mutation. J. Bacteriol. 160:15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, Y., F. Buchholz, J. P. P. Muyrers, and A. F. Stewart. 1998. A new logic for DNA engineering using recombination in Escherichia coli. Nat. Genet. 20:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zubko, E., C. Scutt, and M. Meyer. 2000. Intrachromosomal recombination between attP regions as a tool to remove selectable marker genes from tobacco transgenes. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:442-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]