Abstract

Pharmaceuticals, culture media used for in vitro diagnostics and research, human body fluids, and environments can retain very low ethanol concentrations (VLEC) (≤0.1%, vol/vol). In contrast to the well-established effects of elevated ethanol concentrations on bacteria, little is known about the consequences of exposure to VLEC. We supplemented growth media for Staphylococcus aureus strain DSM20231 with VLEC (VLEC+ conditions) and determined ultramorphology, growth, and viability compared to those with unsupplemented media (VLEC− conditions) for prolonged culture times (up to 8 days). VLEC+-grown late-stationary-phase S. aureus displayed extensive alterations of cell integrity as shown by scanning electron microscopy. Surprisingly, while ethanol in the medium was completely metabolized during exponential phase, a profound delay of S. aureus post-stationary-phase recovery (>48 h) was observed. Concomitantly, under VLEC+ conditions, the concentration of acetate in the culture medium remained elevated while that of ammonia was reduced, contributing to an acidic culture medium and suggesting decreased amino acid catabolism. Interestingly, amino acid depletion was not uniformly affected: under VLEC+ conditions, glutamic acid, ornithine, and proline remained in the culture medium while the uptake of other amino acids was not affected. Supplementation with arginine, but not with other amino acids, was able to restore post-stationary-phase growth and viability. Taken together, these data demonstrate that VLEC have profound effects on the recovery of S. aureus even after ethanol depletion and delay the transition from primary to secondary metabolite catabolism. These data also suggest that the concentration of ethanol needed for bacteriostatic control of S. aureus is lower than that previously reported.

Staphylococcus aureus is an opportunistic human pathogen (27) causing significant morbidity and mortality in both community-acquired and nosocomial infections. Examples of clinical disease include infective endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and infections associated with the use of medical devices such as catheters and implants (16, 26). S. aureus is a highly versatile organism capable of surviving under untoward environmental conditions (5), thus representing a major challenge in infection control (20).

In medicine, alcoholic compounds have numerous applications as stabilizers, solvents, and disinfectants. A large variety of therapeutics (typically liquids for oral application, e.g., cough suppressants, expectorants, oral tranquilizer suspensions) contain ethanol at various concentrations. Furthermore, a number of pharmaceuticals for intravenous treatment also contain ethanol at concentrations ranging from 1% (vol/vol) to 96% (vol/vol). Most alcohol-based disinfectants contain ethanol, typically at a concentration of ∼70 to 85% (vol/vol). As an example, antibiotic lock therapy of implanted intravenous catheters uses alcohol as an antimicrobial disinfectant (9) and is widely applied, particularly in pediatrics (34). Finally, ethanol may also be used for food preservation (35). Given the large range of ethanol concentrations in the different preparations, and considering washout, dilution, and evaporation, the actual concentrations in situ are anticipated to be more diverse and would include very low ethanol concentrations (VLEC); hence, a fundamental understanding of the effects of VLEC on bacterial physiology is important.

In addition to the above applications, ethanol or related alcohols are routinely used in medical microbiology for in vitro testing as a solvent: According to CLSI (formerly NCCLS) guidelines (30), 95% ethanol or methanol is recommended to dissolve various macrolides, chloramphenicol, and rifampin. The final concentration of ethanol in the medium depends on the concentration of the antimicrobial selected; for instance, a solution containing 10 μg/ml of the respective antimicrobial also contains 0.1% (vol/vol) ethanol. Furthermore, bacterial genetic research employing erythromycin resistance as a marker for selection typically employs final concentrations of 10 μg/ml erythromycin, i.e., a solution containing 0.1% (vol/vol) ethanol.

The bactericidal activity of ethanol is due to several factors: disruption of membrane structure or function (1, 12, 15, 36); interference with cell division, affecting steady-state growth (12); variations in fatty acid composition and protein synthesis (8); inhibition of nutrient transport via membrane-bound ATPases (4); alteration of membrane ΔpH (4, 40) and membrane potential (Δψ) (40); and a decrease in intracellular pH (4, 18, 40). In a recent study with the gram-positive organism Bacillus subtilis, it was demonstrated that treatment with subinhibitory concentrations of ethanol (not affecting vegetative growth) inhibited the initiation of spore development through a selective blockage of key developmental genes under the control of the master transcription factor Spo0A∼P (14). These toxic effects have been described for a wide variety of microbial species, and for use of different concentrations of ethanol, ranging from 2.5% to 70% (1, 2, 8, 10, 19, 25, 36). Surprisingly, very little is known about the physiological effects of VLEC. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the effects of VLEC on medically important staphylococci at a concentration frequently encountered in the hospital and laboratory. In this study, we report major effects of VLEC on S. aureus cell integrity, survival, and growth recovery, and we describe the effects of VLEC on metabolism and transcription of select staphylococcal genes.

(This work is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree at the University of Saarland, Homburg/Saar, Germany, for I. Chatterjee.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Staphylococcus aureus DSM20231 (37) (from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) (ATCC 12600; Cowan serotype 3) was used throughout this study. In select experiments, S. aureus strain SH1000 was used (17). Strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI; Oxoid) medium or on Mueller-Hinton medium containing 1.5% agar. All bacterial cultures were inoculated from an overnight culture and diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 into BHI incubated at 37°C. For generation of microaerobic growth conditions, Erlenmeyer flasks (100 ml) were incubated with a flask-to-medium ratio of 2:1 and shaken at 150 rpm. For generation of aerobic growth conditions, Erlenmeyer flasks (1 liter) were incubated with a flask-to-medium ratio of 10:1 and shaken at 230 rpm. Sterile-filtered ethanol was added to the BHI medium to a final concentration of 0.1% (vol/vol). For most experiments, this ethanol concentration was selected because it represents a concentration frequently employed in in vitro bacterial genetic research. These medium conditions were designated “VLEC positive” (VLEC+) and compared with unsupplemented media (VLEC−). In the following text, these descriptions are used according to the medium supplementation conditions established upon the start of the cultures; as ethanol is rapidly metabolized or dissipates (see Results), the designation VLEC+ also applies to conditions encountered during later stages of growth without detectable ethanol concentrations in the media. Aliquots (100 μl) were removed at the indicated time points and cell densities, and the pH of the culture medium and CFU were determined. For l-amino acid supplementation experiments, l-amino acid (asparagine, citrulline, glutamine, glutamic acid, glycine, methionine, ornithine, proline, serine, and valine) stock solutions were added to BHI medium at a final concentration of 2 mM; l-arginine was supplemented at either 2 mM or 5 mM. Bacterial growth was assessed by measuring the optical density at 600 nm.

Measurement of membrane potential.

Cells were grown in BHI medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 1, centrifuged, and resuspended 1:3 in fresh medium. To monitor the membrane potential (31), 1 μCi/ml of [3H]tetraphenylphosphonium bromide (TPP+; 26 Ci/mmol) was added. TPP+ is a lipophilic cation which diffuses across the bacterial membrane in response to a trans-negative Δψ. The culture was treated with 0.1% (vol/vol) ethanol after 16 min to estimate the effect of VLEC+ conditions on membrane potential, and samples were filtered and washed as described above. Counts were corrected for nonspecific binding of [3H]TPP+ by subtracting the radioactivity of 10% butanol-treated cell aliquots. For calculation of Δψ, TPP+ concentrations were applied to the Nernst equation, Δψ = (2.3 × R × T/F) × log ([TPP+in]/[TPP+out]), where R is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin, F is Faraday's constant, [TPP+in] is the molar concentration of TPP+ inside the bacterial cells, and [TPP+out] is the molar concentration of TPP+ in the medium. The internal volume of 3.4 μl mg of protein−1 of staphylococcal cells was used for calculation of [TPP+in].

Gene expression.

RNA was isolated from S. aureus grown in BHI medium (VLEC+ or VLEC−) for 3.5, 8, 17, or 22 h. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and mechanically disrupted with a Fast Prep FP120 instrument (Qbiogene, Heidelberg, Germany), and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After treatment with RNase-free DNase I (QIAGEN), total-RNA samples were amplified in an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system using SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) and gyrB primers (forward, gyrB f1 [5′-GACTGATGCCGATGTGGA-3′]; reverse, gyrB r1 [5′-AACGGTGGCTGTGCAATA-3′]) to check for the absence of genomic DNA. Previously transcribed cDNA served as a positive control. RNA was then reverse transcribed (High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit; Applied Biosystems). cDNA was used for real-time amplification with arcA primers (forward, arcA f1 [5′-CTTGGCTATAGGCGTTTCAGAAC-3′]; reverse, arcA r1 [5′-GTCGCCTGCGGATTTTCA-3′]) or adhE primers (forward, adhE f1 [5′-CACAAAGGTATTGCATTAGTTCTAGCA-3′]; reverse, adhE r1 [5′-CGTTACCTGGTCCCACACCTA-3′]) and 100 ng of cDNA per reaction. The level of mRNA expression of different genes was normalized against gyrB, which is constitutively expressed (41). The transcript level for each gene of interest was expressed as the n-fold difference relative to the control gene ( , where ΔCT represents the difference in threshold cycle between the target and control genes).

, where ΔCT represents the difference in threshold cycle between the target and control genes).

Metabolite analysis.

Aliquots of bacteria (2 ml) were centrifuged for 5 min at 21,000 × g and 4°C at the indicated time points. The culture supernatants were removed and adjusted to pH 8 with KOH, and the concentrations of glucose, acetate, ammonia, ethanol, and lactate were determined with kits purchased from R-Biopharm AG (Darmstadt, Germany). The concentrations of free amino acids were determined with a Beckman amino acid analyzer by aminoNova AG (Berlin, Germany).

Gas chromatography.

From the incubation culture (brain heart infusion medium with 0.1% ethanol) with bacteria or without bacteria (n = 2 each), 0.1 ml of sample was taken at time zero and at 2, 4, 7, and 24 h. The samples were analyzed by headspace gas chromatography (80°C; column, 0.1% SP-1000/Carbopak C) with flame ionization detection for ethanol quantification or mass selective detection for identification of ethanol and acetaldehyde (29).

Determination of stationary-phase survival.

Single colonies of S. aureus strains were inoculated into 100-ml flasks containing 50 ml of BHI (unsupplemented or supplemented with ethanol), grown at 37°C, and aerated by shaking at 150 rpm for up to 9 days. Aliquots (200 μl) were harvested at 24-h intervals, and the CFU was determined.

Scanning electron microscopy.

Bacterial cells were harvested at different time points (24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 120 h, and 192 h). The pellet was resuspended in a mixture of 1% formaldehyde-1% glutaraldehyde-0.1% picric acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at room temperature and then stored at 4°C. All formaldehyde solutions were prepared from freshly depolymerized paraformaldehyde. Cell pellets were washed with phosphate buffer and then prepared for scanning electron microscopy. A dense suspension of washed cells was transferred on grids. Cells were dehydrated by use of an ethanol gradient and then subjected to critical-point drying. Subsequently, samples were mounted on aluminum sample holders and sputter coated with platinum, then inspected with an ESEM XL 30 (FEI, The Netherlands) scanning electron microscope at 20 to 30 kV.

RESULTS

Electron microscopy analysis of S. aureus cells grown in the presence of ethanol under microaerobic conditions.

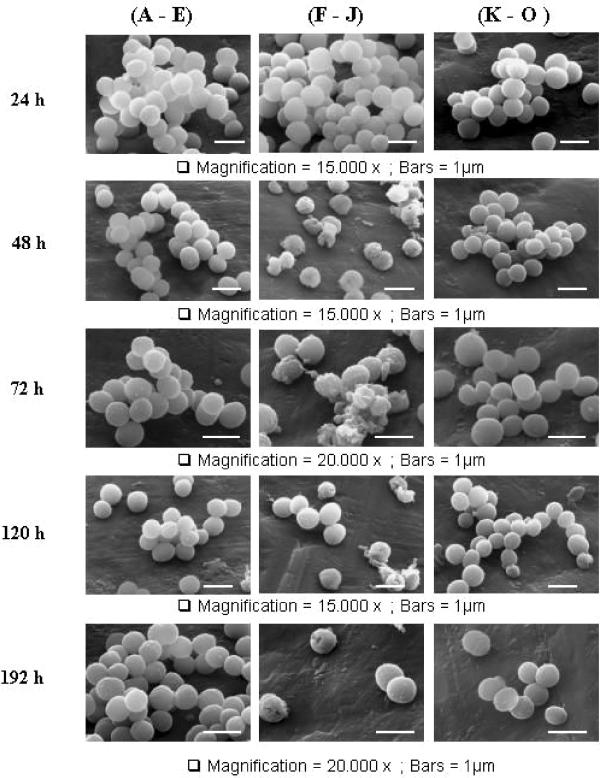

High concentrations of ethanol are bactericidal; however, bacteria can grow in the presence of low concentrations of ethanol (21, 22). These observations led us to question whether morphological changes would be induced upon growth of S. aureus under such conditions. Thus, we examined S. aureus grown under VLEC+ conditions by using scanning electron microscopy at different time points throughout the growth cycle (Fig. 1). No morphological differences were observed (Fig. 1A, F, and K) until between 48 h and 192 h postinoculation, when striking changes could be seen in S. aureus grown in a VLEC+ medium (Fig. 1G to J). The presence of collapsed and broken cells, cell debris, and indentation of the cell surface in these cells suggested the possibility of a weakened cell wall. In contrast, cells grown in the absence of ethanol had more intact cells and a normal smooth, spherical appearance (Fig. 1A to E). Interestingly, the effects of ethanol occur only when the bacterial cultures are grown under microaerobic conditions. Taken together, these data suggest that the effect of VLEC on the growth and/or viability of S. aureus is delayed.

FIG. 1.

Effects of VLEC and arginine on micromorphology of S. aureus DSM20231. Shown are representative scanning electron micrographs of S. aureus DSM20231 grown for various times (24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 120 h, and 192 h) in unsupplemented medium (A to E, top to bottom), under VLEC+ conditions (F to J, top to bottom), or under VLEC+ conditions and supplemented with 5 mM arginine (K to O, top to bottom).

Ethanol delays post-stationary-phase recovery.

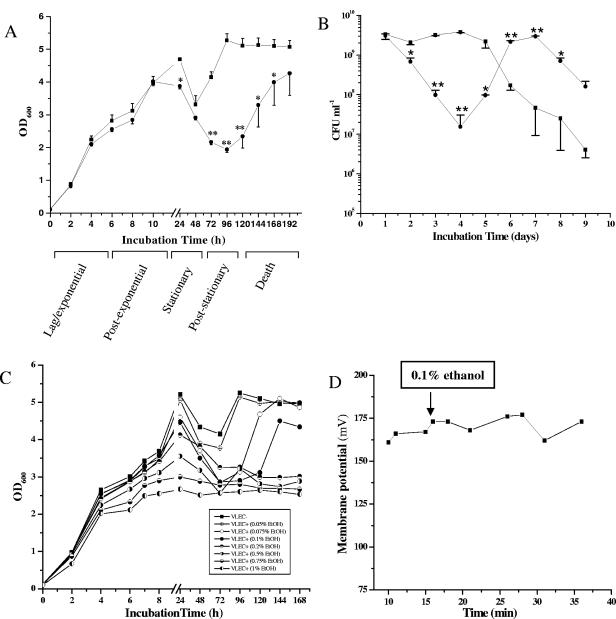

VLEC did not alter the exponential growth rate (Fig. 2A and B); however, it slightly decreased the growth yield (24 h). Between 48 h and 72 h in culture, the cell density for bacteria grown in the absence of ethanol increased, suggesting post-stationary-phase growth. In contrast, bacteria grown under VLEC+ conditions lysed between 24 to 48 h, reaching a nadir in cell density (Fig. 2A) and CFU (Fig. 2B) at 96 h and increasing in cell density after 120 h. These findings were consistent with the morphological observations (Fig. 1). The effect of ethanol on the late stationary phase was dependent on the ethanol concentration (Fig. 2C). Post-stationary-phase growth was delayed at concentrations between 0.075% (vol/vol) and 0.1% (vol/vol), while at more elevated concentrations post-stationary-phase growth was inhibited, and exponential growth (at 24 h) was also affected. In contrast, a concentration of 0.05% (vol/vol) ethanol showed post-stationary-phase growth characteristics indistinguishable from that under VLEC− conditions. S. aureus grown in unsupplemented medium entered the final death phase (defined as the loss of viable counts without a concomitant reduction in optical density) immediately after the post-stationary growth phase (at 96 to 120 h) (5 to 6 days). In contrast, VLEC-treated S. aureus entered the final death phase much later (168 h). To determine if these results were due to strain-specific factors, an identical experiment was performed using strain S. aureus SH1000. The effect of VLEC on strain SH1000 was nearly identical to that on strain DSM20231 (data not shown), suggesting that the response of strain DSM20231 to VLEC is common to S. aureus strains of different genetic backgrounds.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of long-term growth, stationary-phase survival, and membrane potential of S. aureus. (A) Growth analysis (OD600) of S. aureus DSM20231 under VLEC− (▪) and VLEC+ (•) conditions, determined in BHI medium. Single colonies were inoculated into BHI in the absence (▪) or presence (•) of 0.1% (vol/vol) ethanol and incubated at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions for up to 8 days. Data are means ± standard errors of the means of values obtained in three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 (t test). (B) Viability of S. aureus DSM20231. After growth for the indicated time under VLEC− (▪) or VLEC+ (•) conditions, aliquots were removed and CFU/ml was determined in triplicate. Data are means ± standard deviations of values obtained in two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005 (t test). (C) Ethanol concentration-dependent delayed recovery. (D) Membrane potential measurement of S. aureus DSM20231. Addition of ethanol (0.1%) is indicated by an arrow. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

A possible explanation for the delayed post-stationary-phase recovery in the VLEC+ population is the emergence of escape mutants with reduced susceptibility to ethanol. To test this hypothesis, we performed an ethanol susceptibility assay on late-stationary-phase bacteria. VLEC-grown staphylococci (both DSM20231 and SH1000 strains) were grown for 12 h, from post-stationary phase (120 h), in media containing various concentrations of ethanol (0%, 1%, 5%, 10%, 25%, and 50%). These bacteria were just as sensitive to ethanol as bacteria obtained from fresh overnight cultures or organisms grown under VLEC− conditions (data not shown). A second possible explanation for the prolonged recovery time of VLEC-treated bacteria might be inefficient membrane repair. To address this possibility, we determined the membrane potential of S. aureus in the presence of VLEC (Fig. 2D). We were unable to detect any difference in membrane potential in S. aureus DSM20231 after addition of 0.1% ethanol relative to the untreated control. Taken together, these data suggest that VLEC does not facilitate the generation of escape mutants or significantly alter the membrane potential.

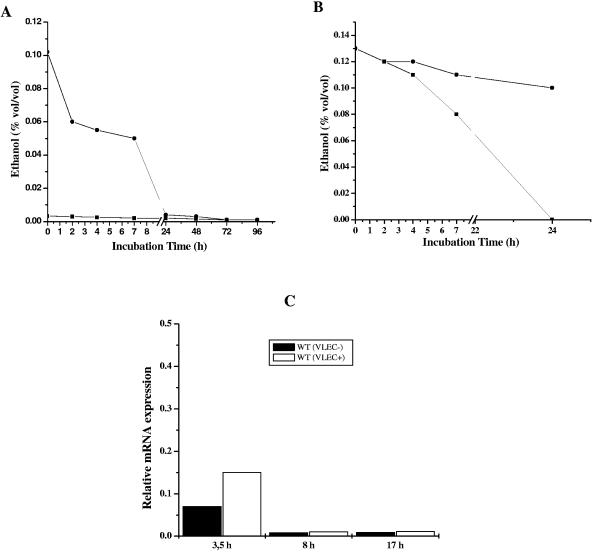

Ethanol is rapidly removed from the culture medium.

Ethanol is a volatile organic alcohol (flash point, 13°C); thus, it was surprising that the effects of VLEC on post-stationary-phase recovery persisted until 120 h (5 days) into the growth cycle. We speculated that ethanol would be lost due to evaporation and/or catabolism well before 120 h; hence, we determined the concentration of ethanol in the culture medium throughout the growth cycle. As expected, the concentration of ethanol in the culture medium began to decrease immediately after inoculation, and by 24 h no ethanol remained (Fig. 3A). To assess if ethanol evaporated or was enzymatically catabolized, VLEC+ supernatants were examined by gas chromatography at various time points after supplementation with ethanol both in the presence and in the absence of S. aureus (Fig. 3B). In the absence of microorganisms, the concentration of ethanol in the medium remained stable over 24 h, while in the presence of S. aureus ethanol was depleted from the culture medium by 24 h, suggesting that the bacteria were catabolizing the ethanol. Concomitantly, under VLEC+ conditions, transcription of adhE (the alcohol-acetaldehyde dehydrogenase gene) was elevated earlier (at 3.5 h) than under VLEC− conditions, indicating a contribution of alcohol dehydrogenase to ethanol catabolization (Fig. 3C). Most importantly, these data demonstrate that the effects of VLEC on late-stationary-phase growth and survival persist long after ethanol has been depleted from the culture medium, and they suggest that recovery from ethanol-induced alteration is a delayed process.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of ethanol in the culture supernatant and effect of alcohol-aldehyde dehydrogenase (adhE) in VLEC exposure. (A) Determination of ethanol levels in the culture supernatant of S. aureus DSM20231 under VLEC− (▪) and VLEC+ conditions (•) at the indicated time points. (B) Estimation of the nonenzymatic loss of ethanol from the culture supernatant with (▪) or without (•) bacteria under VLEC+ conditions using gas chromatography. (C) Real-time RT-PCR quantification of alcohol-aldehyde dehydrogenase (adhE) gene expression in S. aureus with or without VLEC at different time points. Expression of the adhE gene in S. aureus DSM20231 was determined in populations grown under VLEC− or VLEC+ conditions by real-time RT-PCR at different times as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are transcript quantities relative to the internal control (gyrB) transcript, expressed as n-fold increase. The x axis denotes time (hours). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

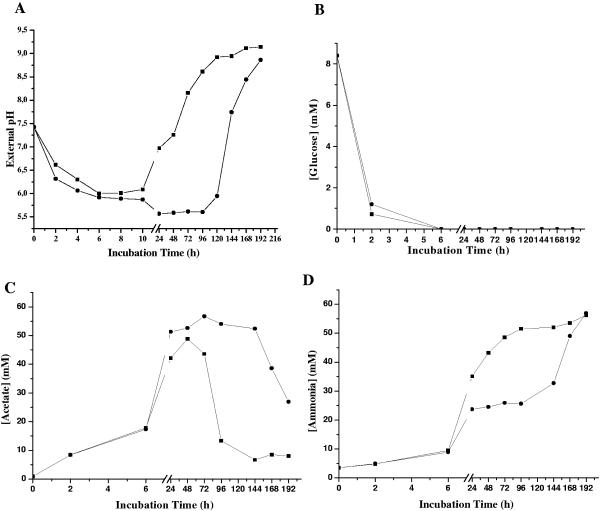

Ethanol delays acetate catabolism and ammonia accumulation.

In VLEC+ cultures, the onset of post-stationary-phase growth was delayed, suggesting that VLEC impaired the metabolism of nonpreferred carbon sources. To determine if VLEC affects metabolism, DSM20231 was grown in VLEC+ medium, and the pH was measured; pH is an indicator of organic acid production. During the first 10 h of incubation, the pHs of the culture medium were nearly identical, irrespective of the presence of ethanol (Fig. 4A). In the absence of ethanol, the pH of the culture medium began to increase at 24 h postinoculation, and by 192 h (8 days), it was alkaline (pH 9.1). In contrast, under VLEC+ conditions, the pH values remained acidic (pH 5.5) until nearly 120 h (5 days). An ethanol-induced inhibition of medium alkalinization can be caused by either a decreased catabolism of organic acids and/or a decreased accumulation of ammonia. To determine which of these two possibilities was responsible for the observed pH difference, we measured the concentrations of glucose, acetate, ethanol, lactic acid, and ammonia in the culture medium. During the exponential phase of growth, the catabolization of glucose was unaffected by the presence of ethanol (Fig. 4B). Similarly, VLEC did not affect the accumulation or depletion of lactic acid in the culture medium (maximum lactate concentrations were 5.77 mM in VLEC− medium and 6.8 mM in VLEC+ medium). The accumulation of acetate in the culture medium was also found to be unaffected by VLEC; however, in VLEC-treated cultures, the depletion of acetate was greatly delayed (Fig. 4C). Additionally, VLEC delayed the accumulation of ammonia (Fig. 4D) until after 144 h, coinciding with the onset of acetate catabolism and the recovery of viable counts and cell density.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of external pH and levels of metabolites of the culture supernatant. External pH (A) and levels of glucose (B), acetate (C), and ammonia (D) in the culture supernatant of S. aureus DSM20231 were determined under VLEC− (▪) and VLEC+ (•) conditions at the indicated time points. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Ethanol affects bacterial uptake of specific amino acids from the culture medium.

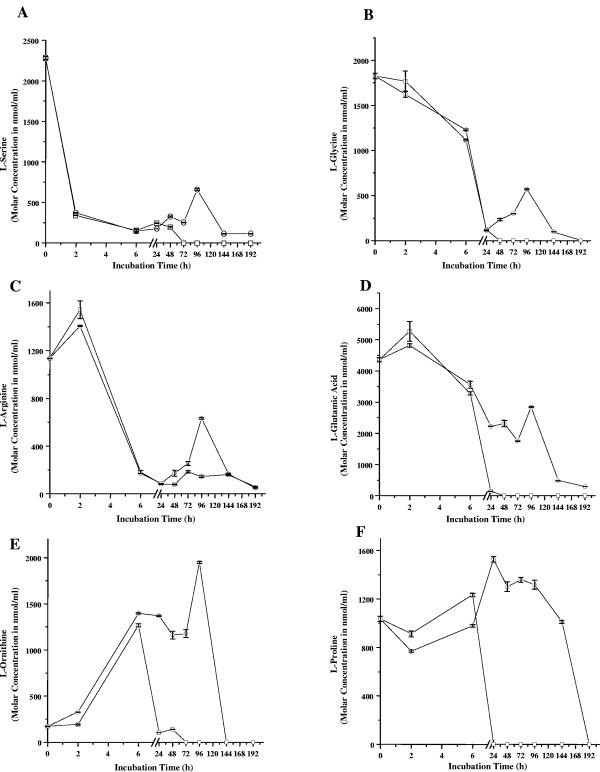

The accumulation of ammonia in the culture medium is an indication of amino acid catabolism. As stated above, VLEC+ conditions reduced the accumulation of ammonia in the culture medium until after 144 h (Fig. 4D), leading us to hypothesize that low concentrations of ethanol affect amino acid catabolism. To test this hypothesis, the concentrations of select free amino acids in the culture medium were determined during growth under VLEC+ conditions and were compared to respective determinations in VLEC− cultures. Serine, glycine, and arginine were depleted from the growth medium irrespective of the presence of ethanol (Fig. 5A, B, and C). In contrast, glutamic acid, ornithine, and proline (Fig. 5D, E, and F) were depleted from the culture medium only after growth resumed, resulting in the delayed accumulation of ammonia. In contrast to the other amino acids tested, ornithine accumulated in the medium during growth. Staphylococci use an arginine-ornithine antiporter to transport arginine into the cell; hence, ornithine concentrations increase as arginine concentrations decrease. As the availability of carbon and/or nitrogen becomes limited, staphylococci can catabolize ornithine. VLEC+ conditions delayed the catabolism of ornithine relative to VLEC− conditions.

FIG. 5.

Depletion of free amino acids from the BHI medium. Shown are concentrations of free amino acids l-serine (A), l-glycine (B), l-arginine (C), l-glutamic acid (D), l-ornithine (E), and l-proline (F) in BHI culture medium of S. aureus DSM20231 grown under VLEC− (□) and VLEC+ (○) conditions. Data are mean molar concentrations (nmol/ml) ± standard deviations of two independent experiments.

Surprisingly, the difference in amino acid uptake was only detectable during or after the stationary phase of growth after the ethanol was gone (Fig. 3A), while exponential-phase amino acid catabolism was independent of ethanol. Taken together, these data indicate that the effect of low ethanol concentrations can persist long after the ethanol has been consumed.

Arginine restores post-stationary-phase recovery under VLEC+ conditions.

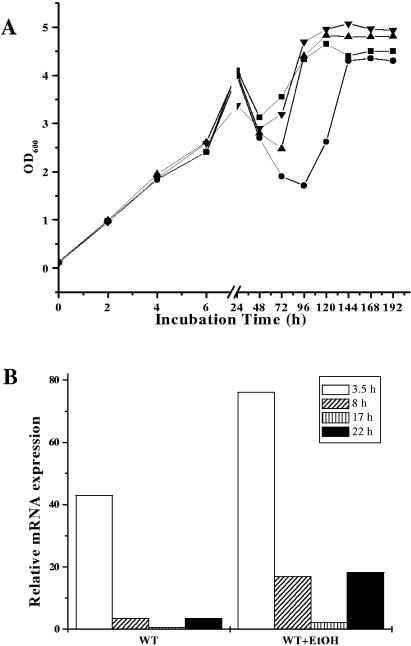

Amino acid catabolism is an important source of carbon and energy. The selective depletion of amino acids from the culture medium (Fig. 6) led us to speculate that supplementation of the culture medium with a depleted amino acid would restore post-stationary-phase growth. We tested this hypothesis by supplementation of VLEC cultures with single amino acids at a concentration of 2 mM and assessed their growth and viability. Interestingly, only arginine restored the post-stationary-phase recovery and viability (Fig. 6A; also data not shown). The catabolism of arginine usually involves the arginine deiminase (ADI) pathway. To ascertain if VLEC+ conditions resulted in increased transcription of genes of the ADI pathway, we determined the relative concentration of mRNA for the arcA gene (encoding arginine deiminase) by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (Fig. 6B). Consistent with our hypothesis, arcA transcript levels were significantly greater at 3.5 h, 8 h, 17 h, and 22 h in staphylococci grown under VLEC+ relative to VLEC− conditions.

FIG. 6.

(A) Effect of l-arginine supplementation. S. aureus DSM20231 was grown under VLEC− (▪) or VLEC+ (•) conditions, or in VLEC supplemented with 2 mM l-arginine (▴), or in VLEC with 5 mM l-arginine (▾) in BHI medium, and cell densities were determined as described in Fig. 2. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Real-time RT-PCR quantification of microaerobic arcA (arginine deiminase) gene expression. Expression of the arcA gene in S. aureus DSM20231 populations grown with or without VLEC was determined by real-time RT-PCR at different time intervals as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are transcript quantities relative to the internal control (gyrB) transcript, expressed as n-fold increase.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that the transition from primary to secondary metabolite catabolism is delayed by VLEC. S. aureus preferentially catabolizes glucose for carbon and energy, a process resulting in the accumulation of organic acids in the culture medium (24, 38, 39). Our results are consistent with these observations, as glucose was rapidly consumed and the pH of the culture medium decreased due to the accumulation of lactate and acetate. Notably, the consumption of glucose and the acidification of the culture medium were unaffected during exponential phase under VLEC+ conditions; however, VLEC resulted in a delayed transition from glucose catabolism to secondary metabolite catabolism (7, 39). The delayed transition to the catabolism of nonpreferred carbons sources also resulted in decreased amino acid catabolism (Fig. 5). In S. aureus, acetate catabolism requires tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle activity, but staphylococci lack the glyoxylate shunt. Hence, for every 2 carbons that enter into the TCA cycle as acetyl coenzyme A, 2 carbons are lost during the oxidative decarboxylation reactions. That is to say, if any carbons leave the TCA cycle in the form of biosynthetic intermediates, then those carbons must be replaced for the TCA cycle to continue to function. Staphylococci replace lost carbons through the catabolism of amino acids; hence, a decrease in acetate catabolism results in a decrease in amino acid catabolism.

Additionally, VLEC+ conditions selectively inhibited the utilization of amino acids such as glutamate, proline, and ornithine. d-Glutamate is found in the second position of the peptidoglycan stem peptides in virtually all species analyzed thus far (33) and is essential for growth in Escherichia coli (28) and S. aureus (6, 11, 13). The other “glutamate family” amino acids ornithine and proline can be converted into glutamate: ornithine by the ornithine aminotransferase (SA0818) and the Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase (SA2341) and proline by the proline dehydrogenase (SA1585). Thus, the inability to acquire, or synthesize, glutamate under VLEC+ conditions may contribute to cell lysis in the presence of ethanol.

Ethanol enhances the ability of staphylococci to form a biofilm (23). Recent transcriptional profiling data on staphylococci growing in biofilms has suggested that the bacteria are growing anaerobically (3, 32, 42). Consistent with that suggestion, these studies noted increased expression of the anaerobic alternative energy-generating ADI pathway (3, 32, 42). The ADI pathway is composed of three enzymes, arginine deiminase (arcA), ornithine transcarbomoylase (arcB), and carbamate kinase (arcC). Together, these enzymes convert arginine to ornithine, ammonia, and carbon dioxide, yielding 1 mol of ATP per mol of arginine consumed. Our data demonstrate that ethanol up-regulates expression of the ADI pathway, leading us to speculate that ethanol enhances biofilm formation, in part, through an alteration of the metabolic flux toward the ADI pathway.

In conclusion, to our knowledge this is the first report demonstrating the effects of VLEC on S. aureus growth, viability, metabolism, and cell wall morphology. These effects of VLEC were evident only after the complete depletion of ethanol from the culture medium, suggesting that bacterial recovery from, and adaptation to, ethanol stress is a prolonged process. These observations are incongruent with a prevailing dogma, i.e., that bacteria rapidly adapt or die when exposed to disinfectants, and they open new perspectives in our understanding of bacterial senescence in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of antiseptic agents.

Acknowledgments

This work has received grant support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Specialized Priority Programme 1047 and 1130, to M.H.) and in part by a grant from the Medical Faculty of the University of Saarland (HOMFOR, 2004, to M.H.). This paper is number 14628 in the University of Nebraska Agriculture Research Division journal series.

We are indebted to M. Laue, N. Pütz, C. Schröder, M. Josten, and K. Hilgert for technical help in part of the experiments, to S. Foster (Sheffield, United Kingdom) for S. aureus strain SH1000, and to H. Labischinski, J. Gehrke, and M. Haber for helpful suggestions and discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barker, C., and S. F. Park. 2001. Sensitization of Listeria monocytogenes to low pH, organic acids, and osmotic stress by ethanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1594-1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu, T., and R. K. Poddar. 1994. Effect of ethanol on Escherichia coli cells. Enhancement of DNA synthesis due to ethanol treatment. Fol. Microbiol. (Praha) 39:3-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beeken, K. E., P. M. Dunman, F. McAleese, D. Macapagal, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, J. S. Blevins, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2004. Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 186:4665-4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowles, L. K., and W. L. Ellefson. 1985. Effects of butanol on Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50:1165-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, P. F., S. J. Foster, E. Ingham, and M. O. Clements. 1998. The Staphylococcus aureus alternative sigma factor σB controls the environmental stress response but not starvation survival or pathogenicity in a mouse abscess model. J. Bacteriol. 180:6082-6089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterjee, A., and F. E. Young. 1972. Regulation of the bacterial cell wall: isolation and characterization of peptidoglycan mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 111:220-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee, I., P. Becker, M. Grundmeier, M. Bischoff, G. A. Somerville, G. Peters, B. Sinha, N. Harraghy, R. A. Proctor, and M. Herrmann. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus ClpC is required for stress resistance, aconitase activity, growth recovery, and death. J. Bacteriol. 187:4488-4496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiou, R. Y., R. D. Phillips, P. Zhao, M. P. Doyle, and L. R. Beuchat. 2004. Ethanol-mediated variations in cellular fatty acid composition and protein profiles of two genotypically different strains of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2204-2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dannenberg, C., U. Bierbach, A. Rothe, J. Beer, and D. Korholz. 2003. Ethanol-lock technique in the treatment of bloodstream infections in pediatric oncology patients with Broviac catheter. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 25:616-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dombek, K. M., and L. O. Ingram. 1984. Effects of ethanol on the Escherichia coli plasma membrane. J. Bacteriol. 157:233-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fass, R. J., J. Carleton, C. Watanakunakorn, A. S. Klainer, and M. Hamburger. 1970. Scanning-beam electron microscopy of cell wall-defective staphylococci. Infect. Immun. 2:504-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried, V. A., and A. Novick. 1973. Organic solvents as probes for the structure and function of the bacterial membrane: effects of ethanol on the wild type and an ethanol-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 114:239-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good, C. M., and D. J. Tipper. 1972. Conditional mutants of Staphylococcus aureus defective in cell wall precursor synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 111:231-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottig, N., M. E. Pedrido, M. Mendez, E. Lombardia, A. Rovetto, V. Philippe, L. Orsaria, and R. Grau. 2005. The Bacillus subtilis SinR and RapA developmental regulators are responsible for inhibition of spore development by alcohol. J. Bacteriol. 187:2662-2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halegoua, S., and M. Inouye. 1979. Translocation and assembly of outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli. Selective accumulation of precursors and novel assembly intermediates caused by phenethyl alcohol. J. Mol. Biol. 130:39-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrmann, M., M. Weyand, B. Greshake, C. von Eiff, R. A. Proctor, H. H. Scheld, and G. Peters. 1997. Left ventricular assist device infection is associated with increased mortality but is not a contraindication to transplantation. Circulation 95:814-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horsburgh, M. J., J. L. Aish, I. J. White, L. Shaw, J. K. Lithgow, and S. J. Foster. 2002. σB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J. Bacteriol. 184:5457-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang, L., C. W. Forsberg, and L. N. Gibbins. 1986. Influence of external pH and fermentation products on Clostridium acetobutylicum intracellular pH and cellular distribution of fermentation products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:1230-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingram, L. O., and T. M. Buttke. 1984. Effects of alcohols on micro-organisms. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 25:253-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.John, J. F., and N. L. Barg. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus, p. 443-470. In G. C. Mayhall (ed.), Hospital epidemiology and infection control. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 21.Knobloch, J. K., K. Bartscht, A. Sabottke, H. Rohde, H. H. Feucht, and D. Mack. 2001. Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis depends on functional RsbU, an activator of the sigB operon: differential activation mechanisms due to ethanol and salt stress. J. Bacteriol. 183:2624-2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knobloch, J. K., M. A. Horstkotte, H. Rohde, P. M. Kaulfers, and D. Mack. 2002. Alcoholic ingredients in skin disinfectants increase biofilm expression of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:683-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knobloch, J. K., S. Jager, M. A. Horstkotte, H. Rohde, and D. Mack. 2004. RsbU-dependent regulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation is mediated via the alternative sigma factor σB by repression of the negative regulator gene icaR. Infect. Immun. 72:3838-3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohler, C., C. von Eiff, G. Peters, R. A. Proctor, M. Hecker, and S. Engelmann. 2003. Physiological characterization of a heme-deficient mutant of Staphylococcus aureus by a proteomic approach. J. Bacteriol. 185:6928-6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacy, R. W. 1968. Antibacterial action of human skin. In vivo effect of acetone, alcohol and soap on behaviour of Staphylococcus aureus. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 49:209-215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lew, D., J. Schrenzel, P. Francois, and P. Vaudaux. 2001. Pathogenesis, prevention, and therapy of staphylococcal prosthetic infections. Curr. Clin. Top. Infect. Dis. 21:252-270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowy, F. D. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:520-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lugtenberg, E. J. J., H. J. W. Wijsman, and D. V. Zaane. 1973. Properties of a d-glutamic acid-requiring mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 114:499-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maurer, H. H., T. Kraemer, C. Kratzsch, L. D. Paul, F. T. Peters, D. Springer, R. F. Staack, and A. A. Weber. 2002. What is the appropriate analytical strategy for effective management of intoxicated patients?, p. 61-75. In M. Balikova and E. Navakova (ed.), Proceedings of the 39th International TIAFT Meeting in Prague 2001. Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic.

- 30.NCCLS. 2002. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twelfth informational supplement. NCCLS document M100-S12. NCCLS, Wayne, Pa.

- 31.Pag, U., M. Oedenkoven, N. Papo, Z. Oren, Y. Shai, and H.-G. Sahl. 2004. In vitro activity and mode of action of diastereomeric antimicrobial peptides against bacterial clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:230-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Resch, A., R. Rosenstein, C. Nerz, and F. Götz. 2005. Differential gene expression profiling of Staphylococcus aureus cultivated under biofilm and planktonic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2663-2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schleifer, K. H., and O. Kandler. 1972. Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriol. Rev. 36:407-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seifert, H. 2005. Central venous catheters, p. 293-326. In H. Seifert, B. Jansen, and B. M. Farr (ed.), Catheter-related infections, 2nd ed., Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 35.Seiler, D. A. L., and N. J. Russell. 1991. Ethanol as a food preservative, p. 153-171. In N. J. Russell and G. W. Gould (ed.), Food preservatives. Blackie, London, England.

- 36.Silveira, M. G., M. Baumgartner, F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 2004. Effect of adaptation to ethanol on cytoplasmic and membrane protein profiles of Oenococcus oeni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2748-2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silvestri, L. G., and L. R. Hill. 1965. Agreement between deoxyribonucleic acid base composition and taxometric classification of gram-positive cocci. J. Bacteriol. 90:136-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Somerville, G. A., M. S. Chaussee, C. I. Morgan, J. R. Fitzgerald, D. W. Dorward, L. J. Reitzer, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus aconitase inactivation unexpectedly inhibits post-exponential-phase growth and enhances stationary-phase survival. Infect. Immun. 70:6373-6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Somerville, G. A., B. Saïd-Salim, J. M. Wickman, S. J. Raffel, B. N. Kreiswirth, and J. M. Musser. 2003. Correlation of acetate catabolism and growth yield in Staphylococcus aureus: implications for host-pathogen interactions. Infect. Immun. 71:4724-4732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terracciano, J. S., and E. R. Kashket. 1986. Intracellular conditions required for the initiation of solvent production by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:86-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolz, C., C. Goerke, R. Landmann, W. Zimmerli, and U. Fluckiger. 2002. Transcription of clumping factor A in attached and unattached Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and during device-related infection. Infect. Immun. 70:2758-2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao, Y., D. E. Sturdevant, and M. Otto. 2005. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression in Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms: insights into the pathophysiology of S. epidermidis biofilms and the role of phenol-soluble modulins in formation of biofilms. J. Infect. Dis. 191:289-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]