Abstract

Although DNA breaks stimulate mitotic recombination in plants, their effects on meiotic recombination are not known. Recombination across a maize a1 allele containing a nonautonomous Mu transposon was studied in the presence and absence of the MuDR-encoded transposase. Recombinant A1′ alleles isolated from a1-mum2/a1::rdt heterozygotes arose via either crossovers (32 CO events) or noncrossovers (8 NCO events). In the presence of MuDR, the rate of COs increased fourfold. This increase is most likely a consequence of the repair of MuDR-induced DNA breaks at the Mu1 insertion in a1-mum2. Hence, this study provides the first in vivo evidence that DNA breaks stimulate meiotic crossovers in plants. The distribution of recombination breakpoints is not affected by the presence of MuDR in that 19 of 24 breakpoints isolated from plants that carried MuDR mapped to a previously defined 377-bp recombination hotspot. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that the DNA breaks that initiate recombination at a1 cluster at its 5′ end. Conversion tracts associated with eight NCO events ranged in size from <700 bp to >1600 bp. This study also establishes that MuDR functions during meiosis and that ratios of CO/NCO vary among genes and can be influenced by genetic background.

GENES are recombination hotspots in bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals (reviewed by Lichten and Goldman 1995; Schnable et al. 1998). For example, the ratio between genetic and physical distances within the maize a1 gene is 6.25 cM/Mb (Civardi et al. 1994), as compared to the genome average of 2.4 cM/Mb, a figure that is based on a maize genetic map that consists of 5917 cM (Lee et al. 2002). Recombination breakpoints are not evenly distributed across some of these genic hotspots (Eggleston et al. 1995; Patterson et al. 1995; Xu et al. 1995). For example, a 377-bp sequence at the 5′ coding region of the a1 locus is a recombination hotspot that exhibits a recombination rate of 16.1 cM/Mb (Xu et al. 1995).

Recombination events are of two types: reciprocal crossovers (COs) or nonreciprocal noncrossovers (NCOs), such as gene conversions. Detailed analyses of gene conversion events in Drosophila and fungi have established that: (1) conversion tract lengths are relatively short and continuous [e.g., they average ∼350 bp in Drosophila (Hilliker et al. 1994)] and (2) gene conversions exhibit a phenomenon termed polarity [e.g., DNA sequences near one end of the rosy locus of Drosophila and the ARG4 and HIS4 loci of yeast (Schultes and Szostak 1990; Detloff et al. 1992) exhibit higher rates of gene conversion than do sequences at the other end of these loci]. In most cases, higher frequencies occur at the 5′ ends of these genes.

In most plants, gene conversion and double-crossover events cannot be distinguished. Even so, in the absence of strong negative interference, intragenic double crossovers are expected to occur only very rarely. Although putative gene conversions were reported in maize as early as 1986 (Dooner 1986), only a few conversion tracts have been molecularly characterized (Xu et al. 1995; Dooner and Martinez-Ferez 1997b; Mathern and Hake 1997; Li et al. 2001; Yao et al. 2002).

Several models have been proposed to explain the mechanism responsible for meiotic recombination (Holliday 1964; Resnick 1976; Szostak et al. 1983). The most widely accepted of these are based upon the double-strand break (DSB) repair model (Szostak et al. 1983; Sun et al. 1991) in which differential resolution of double-Holliday junction (DHJ) intermediates results in COs or NCOs. Evidence in support of this model has been obtained from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other simple model organisms. The meiosis-induced DSBs predicted by this model to initiate meiotic recombination have been observed at a number of loci (Sun et al. 1989, 1991; Game 1992; Zenvirth et al. 1992; de Massy and Nicolas 1993; Fan et al. 1995; Liu et al. 1995). Moreover, several studies have demonstrated the existence of recombination intermediates of the types postulated in the model, i.e., joint molecules (Collins and Newlon 1994; Schwacha and Kleckner 1994; Schwacha and Kleckner 1995) and heteroduplex DNA (White et al. 1985; Lichten et al. 1990; Goyon and Lichten 1993; Nag and Petes 1993). More recently, Allers and Lichten (2001) proposed a modified DSB repair model. In this model, COs and NCOs are similarly initiated by DSBs but following resection and single end invasion (SEI) only some result in DHJs that can resolve as COs; the remainder are processed via the synthesis-dependent strand annealing pathway and resolve as NCOs. The identification of SEI intermediates in meiosis provides physical evidence for this modified model (Hunter and Kleckner 2001). This model is further supported by the identification of meiotic-related mutants that disrupt SEI formation and drastically reduce the production of COs but not NCOs (Borner et al. 2004).

It is thought that meiotic recombination in plants shares at least some mechanistic aspects with yeast (Xu et al. 1995; Puchta et al. 1996; Puchta and Hohn 1996). Due to technical barriers, less is known about the molecular nature of meiotic recombination in plants than in simple model organisms. Meiotic recombination hotspots in S. cerevisiae correspond to nearby DSB hotspots (reviewed in Lichten and Goldman 1995) that have been recently mapped throughout the genome (Gerton et al. 2000). Available techniques have thus far limited our ability to map DSBs in plants. Therefore, the possible association between DNA breaks and meiotic recombination hotspots in plants has not yet been established. Instead, meiotic recombination hot- and coldspots are identified by physically mapping recombination breakpoints.

Although DSBs have not yet been mapped in plants, there is evidence that DNA breaks play a role in meiotic recombination. For example, processes that enhance the rate of DSB formation stimulate recombination in plants. This conclusion is based on three findings. First, agents that can physically (e.g., X rays and UV irradiation) or chemically (e.g., methylmethanesulfonate and mitomycin C) induce DSBs are able to stimulate intrachromosomal recombination (reviewed in Puchta and Hohn 1996). Second, the expression of the site-specific endonuclease I-SceI in tobacco protoplasts (Puchta et al. 1993, 1996) and HO in somatic cells of Arabidopsis (Chiurazzi et al. 1996) increases the rates of mitotic recombination. Third, autonomous transposons have the ability to increase the rates of recombination-like losses of duplicated regions surrounding corresponding nonautonomous transposons in Arabidopsis and maize (Athma and Peterson 1991; Lowe et al. 1992; Stinard et al. 1993; Xiao et al. 2000; Xiao and Peterson 2000). Because these events either occurred in the absence of meiosis (Athma and Peterson 1991; Xiao et al. 2000; Xiao and Peterson 2000) or did not involve the exchange of flanking markers (Lowe et al. 1992) and therefore did not involve meiotic crossovers, they do not address the question as to whether DSBs stimulate meiotic recombination. Indeed, Dooner and Martinez-Ferez (1997a) have reported that meiotic recombination at the bz1 locus in maize is not stimulated by the germinal excisions of the Ac transposon, which would be expected to introduce DSBs within bz1. The relationship between transposon excision and the stimulation of repair by recombination has not yet been elucidated in other transposon systems in maize.

The a1 locus of maize is an excellent system for the study of meiotic recombination because: (1) intragenic recombination events can be easily identified by their visible nonparental phenotypes (i.e., colored vs. colorless kernels); (2) transposon-tagged a1 alleles have been cloned and characterized, e.g., a1-mum2 and a1::rdt alleles (O'Reilly et al. 1985; Brown et al. 1989a), and a substantial degree of DNA sequence polymorphism exists between these alleles (Xu et al. 1995) thereby facilitating the high-resolution mapping of recombination breakpoints; and (3) genetic markers flanking the a1 locus are available for distinguishing between NCO and CO events.

The a1 locus was used to test the effects of the trans-acting regulatory transposon MuDR (Schnable and Peterson 1986; Chomet et al. 1991; Hershberger et al. 1991; Qin et al. 1991; Hsia and Schnable 1996) on the frequency and distribution of intragenic meiotic recombination events in the vicinity of the Mu1 nonautonomous transposon insertion. Rates of meiotic COs in the vicinity of a Mu1 insertion increase in the presence of MuDR, thereby demonstrating that MuDR is active during meiosis. We hypothesize that this stimulation of meiotic COs occurs via the introduction of DNA breaks generated by MuDR at the Mu1 insertion and that these DNA breaks stimulate meiotic COs in plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic stocks:

The origins and natures of the recessive a1-mum2 and a1::rdt alleles have been reviewed previously (Xu et al. 1995). In summary, the a1-mum2 allele contains a 1.4-kb Mu1 transposon insertion at position −97 and the a1::rdt allele carries a 0.7-kb rdt transposon insertion in the fourth exon. Both of these alleles condition a colorless kernel phenotype in the absence of trans-acting regulatory transposons MuDR and Dotted [Dt], respectively. In the presence of MuDR or Dt, the nonautonomous Mu1 or rdt transposons can excise from a1. If this occurs during kernel development a spotted phenotype results. The shrunken-2 (sh2) gene is located on chromosome 3 ∼0.1 cM centromere distal from the a1 locus (Civardi et al. 1994). Mutations at this locus condition a shrunken kernel phenotype.

Two stocks were derived from a maize line obtained from D. S. Robertson that carried a1-mum2 and many genetically active copies of MuDR. Sibling spotted and nonspotted kernels derived from the same ears were used as the a1-mum2 with and without MuDR stocks, respectively. Consequently, these stocks differ by only the presence or absence of MuDR. The a1-dl stock is as described by Xu et al. (1995).

Isolation of genetic recombinants:

Crosses 1 and 2 were conducted by planting the indicated parents in plots isolated from other maize pollen sources during the summer of 1994.

Cross 1: a1-mum2 Sh2/a1::rdt sh2 (without MuDR) × a1::rdt sh2/a1::rdt sh2.

Cross 2: a1-mum2 Sh2/a1::rdt sh2 (with MuDR) × a1::rdt sh2/a1::rdt sh2.

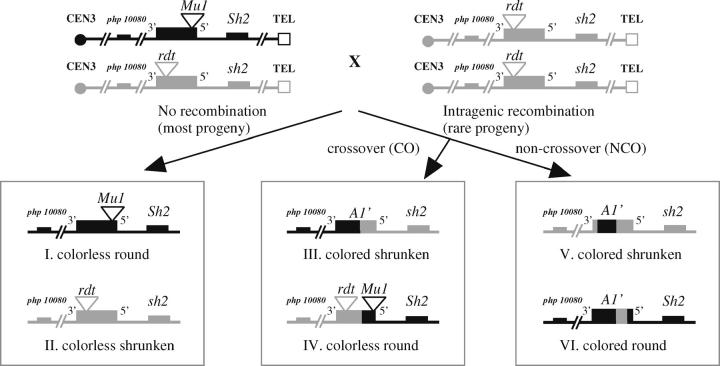

The female parents (listed first) were detasseled prior to anthesis to ensure that they would be pollinated by only the a1::rdt sh2 male parent. As expected, most of the progeny from these crosses had colorless, round (or spotted round when MuDR was present; class I, Figure 1) or colorless, shrunken (class II, Figure 1) kernel phenotypes. However, if intragenic recombination occurred in a1, four recombinant classes (Figure 1, classes III–VI) could also result; three of these can be identified via their nonparental phenotypes. Class IV recombinants condition a parental phenotype and therefore could not be identified. NCOs initiated from the a1-mum2 Sh2 chromosome (class VI) would condition colored round kernels. In the current study, this class could not be analyzed due to the difficulty in distinguishing colored kernels from the very heavily spotted kernels that contain MuDR. The two remaining recombinant classes (III and V) produce colored, shrunken kernels. These kernels were putative recombinants arising from either COs between the Mu1 and rdt transposon insertion sites in the a1-mum2 and a1::rdt alleles (class III, Figure 1) or gene conversion events in which the rdt transposon sequence and its flanking sequences were replaced by the corresponding sequences from the a1-mum2 allele (class V, Figure 1). In either case, the genotype of these kernels was designated A1′ sh2/a1::rdt sh2. To verify and purify the putative recombinant alleles, colored shrunken kernels from crosses 1 and 2 were planted and subjected to cross 3. Colored, round kernels from cross 3 were then planted and the resulting plants were self-pollinated (cross 4).

Cross 3: A1′ sh2/a1::rdt sh2 × a1-dl Sh2/a1-dl Sh2.

Cross 4: A1′ sh2/a1-dl Sh2 self.

Figure 1.—

Isolation of intragenic recombinant A1′ alleles. The parents of and the progeny resulting from crosses 1–2 are illustrated. Chromosomes from the a1-mum2 and a1::rdt sh2 stocks are illustrated in black and gray, respectively. The RFLP marker php10080 and the a1 and sh2 genes are represented by black (if derived from a1-mum2 chromosome) or gray (if derived from a1::rdt chromosome) boxes. Triangles indicate the positions of Mu1 and rdt transposon insertions in the a1 gene. Class III and IV COs arise following DNA breaks on either chromosome. Class V and VI NCOs arise following breaks on the a1::rdt- and a1-mum2-containing chromosomes, respectively. Only the colored shrunken recombinants (classes III and V) were characterized in this study. Class I progeny will be spotted if they carry MuDR.

The colored, shrunken kernels resulting from cross 4 were expected to be homozygous for the recombinant chromosome. The two types of recombination events that gave rise to A1′ alleles (i.e., CO and NCO) were distinguished using two genetic markers that flank the a1 locus on chromosome 3L (Civardi et al. 1994). RFLP marker php10080 is 2 cM centromere-proximal to the a1 locus and the phenotypic marker, sh2, is 0.09 cM centromere-distal to the a1 locus.

Generating plasmid clones for sequencing the 3′ regions of a1-mum2 and a1::rdt:

Within the 1.2-kb interval defined by the insertion sites of Mu1 and rdt, 20 DNA sequence polymorphisms exist between the a1-mum2 (GenBank accession no. AF347696) and a1::rdt alleles (GenBank accession no. AF072704). To sequence the region proximal to the rdt insertion site, the 10-kb a1::rdt clone pE10 (Xu et al. 1995) was digested with SalI and a 2.6-kb fragment that contains the 3′ region of the a1::rdt allele was subcloned into pBKS (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to create pSL2.6. Clone pSL2.6 was subsequently digested with SacI or KpnI to generate two overlapping subclones: 1.5-kb pSC1.5 and 1.4-kb pKN1.4, respectively. Clones pSL2.6, pSC1.5, and pKN1.4 were used as templates for sequencing the proximal region of the a1::rdt allele. A 1.0-kb fragment resulting from the SacI digestion of the 3.0-kb a1-mum2 subclone pYEN1 (Xu et al. 1995) was subcloned into pBKS to generate pSC1.0. Clones pYEN1 and pSC1.0 were used as templates for sequencing the proximal region of the a1-mum2 allele.

Oligonucleotides:

Because the genic sequence of the a1-mum2 allele (AF347696) is identical to the A1-LC allele (Yao et al. 2002), oligonucleotides used as primers for PCR and sequencing were designed from the existing sequence of the A1-LC allele (GenBank accession nos. X05068, AF363390, and AF363391). With the exception of the a1-mum2-specific primer QZ1543, these oligonucleotides could also amplify the a1::rdt allele due to the high degree of sequence identity (98%) between a1-mum2 and a1::rdt.

The sequences of the oligonucleotides used as primers for PCR and sequencing were as follows: QZ1543, 5′ AAA CAT AAA AAC AAT ACG TAA TCC AG 3′ (a1-mum2-specific primer); XX907, 5′ GTG TCT AAA ACC CTG GCG CA 3′; QZ1003, 5′ ATA ATA GTA GCC TCC CGA ATA A 3′; XX231, 5′ GCC AAA CTC TGA TTC GCT CCG TG 3′; XX390, 5′ TCG GCT TGA TTA CCT CAT TCT 3′; XX025, 5′ GGT AGG GCA GCG TGT GGT GTT 3′ (Xu et al. 1995); and XX026, 5′ GAG GTC GTC GAG GTG GAT GAG CTG 3′ (Xu et al. 1995). The positions of the primers within the a1 gene are illustrated in Figure 2A.

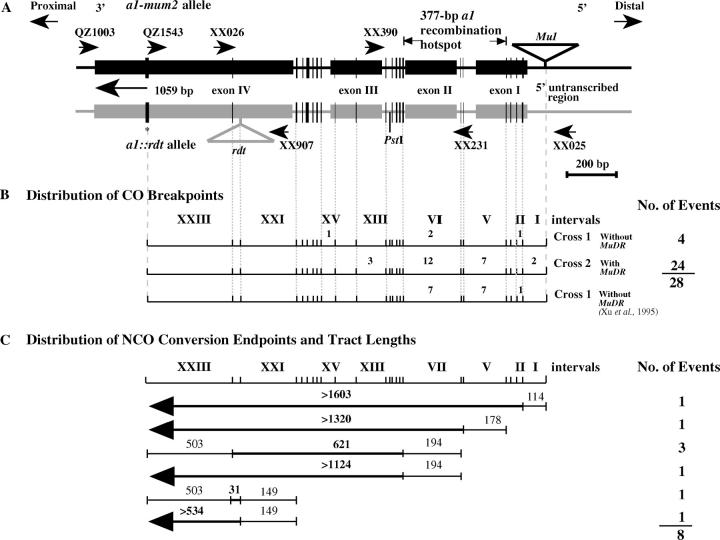

Figure 2.—

Physical mapping of CO breakpoints and NCO conversion tracts. (A) Schematic of the a1-mum2 and a1::rdt alleles in which boxes and triangles represent exons and transposon insertions, respectively. The RFLP marker php10080 and the sh2 locus are proximal and distal to the a1 locus, respectively. The positions of primers used for PCR amplification and sequencing and the diagnostic PstI site are indicated. The a1 gene is separated into 23 intervals defined by the 24 polymorphisms (vertical lines) between the a1::rdt and a1-mum2 alleles. The width of a given vertical bar is proportional to the number of base pairs involved in the polymorphism. The 3′-most polymorphic site (a 32-bp insertion/deletion) is indicated by an asterisk. Sequences 1059 bp 3′ of this site are identical between the a1::rdt and a1-mum2 alleles. (B) Locations of CO recombination breakpoints associated with A1′ alleles. Intervals are defined by the polymorphic sites shown in A. The numbers of recombination breakpoints that resolved in each interval are indicated. The 377-bp recombination hotspot identified previously (Xu et al. 1995) is indicated. Data from Xu et al. (1995) are provided for reference. (C) Locations of NCO conversion endpoints and sizes of conversion tracts associated with eight A1′ alleles isolated from crosses 1 and 2. When possible, conversion tract endpoints were mapped relative to pairs of DNA sequence polymorphisms. Sequences confirmed to be included in the conversion tract are measured in base pairs above the bold lines. Conversion tract endpoints can be positioned relative to the nearest polymorphism and the size of the tract is equal to or less than the length of the thin line. The proximal ends of four conversion tracts (arrows on left side of bold lines) lie to the proximal side of the polymorphic site indicated by an asterisk in A. The numbers of A1′ alleles with the indicated type of conversion tract are indicated on the right.

Polymerase chain reaction:

PCR was conducted for 40 cycles on a programmable thermal controller (MJ Research, Watertown, MA) as follows: denaturation was conducted at 94° for 1 min, annealing at the indicated temperature for 50 sec, and extension at 72° for 1 min. The annealing temperature varied among primer pairs. The annealing temperature was 3° below the lower of the melting temperatures [2 × (A + T) + 4 × (G + C)] of the two primers used in the PCR reaction. PCR reactions included 0.2 mm dNTP (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ), 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 μm of each primer, and Taq polymerase in a total volume of 25 μl. In those instances where nonspecific bands amplified, “hot start” PCR was utilized (Newton et al. 1989; Chou et al. 1992).

Mapping the breakpoints of COs and the distal (5′) endpoints of conversion tracts relative to a diagnostic PstI site:

On the basis of the strategy used to select recombinants, the breakpoints of all COs and the distal endpoints of all conversion tracts of NCOs recovered in this experiment were expected to fall within the 1.2-kb interval defined by the Mu1 and rdt insertion sites in each of the parental a1 alleles (Figure 2A). Previously, Xu et al. (1995) identified a diagnostic PstI site within this 1.2-kb interval that can distinguish between a1-mum2 and a1::rdt derived sequences. This site is present in the a1::rdt allele, but absent from the a1-mum2 allele. Thus, PstI digestion of PCR-amplified recombinant alleles can be used to map the position of the breakpoint of each CO or the distal endpoint of each gene conversion tract relative to this site.

Primers (XX025 and XX026) were used to PCR amplify this 1.2-kb interval from each recombinant allele (Figure 2A). The 1.2-kb PCR products were fractionated by electrophoresis, purified by binding to NA45 DEAE membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH), and subjected to PstI digestion. If a given PCR product was digested by PstI, the breakpoint of the CO or the distal endpoint of the conversion tract associated with the corresponding A1′ allele did not extend 5′ of this diagnostic PstI site. Alternatively, if the PCR product was resistant to PstI digestion, the breakpoint of the CO or the distal endpoint of the conversion tract was between the diagnostic PstI site and the Mu1 insertion site. Thirty-six of the 40 A1′ alleles were successfully amplified and mapped relative to the diagnostic PstI site.

PCR-based sequencing of the recombinant A1′ alleles:

Once a CO breakpoint or conversion tract endpoint was mapped relative to the diagnostic PstI site, the region of the corresponding A1′ allele that contained the recombination endpoint was PCR amplified, purified, and sequenced. Purified PCR products amplified using primers XX025 and XX026 from each of the 36 A1′ alleles were used as templates for sequencing. For those 30 alleles that had breakpoints or endpoints distal to the polymorphic PstI site, primers XX390 and XX025 were used for sequencing. For those 6 alleles with breakpoints or endpoints proximal to the polymorphic PstI site, primers XX231 and XX026 were used for sequencing (Figure 2A). The positions of each CO breakpoint and the conversion tract endpoints proximal or distal to the polymorphic PstI site were identified by comparing the DNA sequence polymorphisms present in a given recombinant A1′ allele to those in a1-mum2 and a1::rdt.

RESULTS

Isolation of recombination events:

Intragenic recombination events were isolated at the a1 locus as illustrated in Figure 1. The a1-mum2 and a1::rdt alleles used in these crosses both condition a colorless kernel phenotype in the absence of MuDR and Dt, due to resident Mu1 and rdt transposon insertions, respectively. Therefore, most of the progeny from these crosses had a colorless (or spotted in the presence of MuDR) kernel phenotype and genotypes of either a1-mum2 Sh2/a1::rdt sh2 or a1:rdt sh2/a1::rdt sh2. However, colored kernels were recovered in rare cases as a result of intragenic recombination that led to the generation of chimeric alleles with restored a1 gene function. These functional recombinant alleles were designated A1′.

To test the effect of the trans-acting regulatory element MuDR on CO frequency, colored shrunken kernels (Figure 1, classes III and V) were selected from parallel crosses without (cross 1) and with (cross 2) MuDR. The colored round class (class VI) was not analyzed for two reasons. First, a previous Mu transposition study in a1 (Lisch et al. 1995) demonstrated that Mu1 excision and repair from a1-mum2 generates fully restored alleles at a low rate, <10−4. Second, coupled with the extremely low rate of reversion at a1-mum2, it is very difficult to distinguish the colored round class (class VI) from the very heavily spotted parental phenotype obtained from cross 2.

Recombinant A1′ alleles isolated from crosses 1 and 2 that were in coupling with the closely linked sh2 mutant allele could have arisen via either COs that resolved between the Mu1 and rdt insertion sites or NCOs having conversion tracts that span the rdt transposon insertion site. These putative colored shrunken recombinants were analyzed as described in materials and methods. The validity of 8 cross 1 and 32 cross 2 recombinants were confirmed via testcrosses and/or RFLP analysis (Table 1) using marker php10080 as described by Xu et al. (1995).

TABLE 1.

Number of recombinantA1′ alleles isolated

| No. confirmed by RFLP analysesb

|

Corrected no.c

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. colored shrunken kernels isolated |

% confirmed by testcrossa | CO + NCO | CO | NCO | CO + NCO | CO | NCO | |

| Cross 1, without MuDR | 17 | 100 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 17 | 11 | 6 |

| Cross 2, with MuDR | 58 | 82 | 32 | 27 | 5 | 47 | 40 | 7 |

Because not all putative recombinants were successfully testcrossed, corrected numbers of recombinants were calculated (see footnote c).

The positions of the 32 CO breakpoints and of the eight NCO conversion tract endpoints are provided in the appendix.

Because not all of the colored shrunken recombinants were classified as COs or NCOs by genetic testcrosses and RFLP analyses, the numbers of CO and NCO events were estimated using the following formulas:

Homogeneity χ2 values for the rates of CO and NCO were calculated on the basis of the corrected number of COs and NCOs (see footnote b in Table 2).

Homogeneity χ2 values for the rates of CO and NCO were calculated on the basis of the corrected number of COs and NCOs (see footnote b in Table 2).

Two genetic markers (php10080 and sh2) that flank the a1 locus were used to distinguish between COs and NCOs. Of the 40 recombinants analyzed with these markers, 32 events displayed nonparental markers and therefore arose via COs; the remaining 8 exhibited parental flanking markers and were therefore determined to have arisen via NCOs (Table 1).

The rates of recombination at the a1 locus in the presence or absence of MuDR are shown in Table 2. The genetic distances (CO + NCO) associated with the 1.2-kb interval derived from cross 1 (without MuDR) and cross 2 (with MuDR) are significantly different (0.008 vs. 0.02 cM). Although the rate of class V NCOs was unaffected by the presence of MuDR, the rate of CO was four times higher in the presence of MuDR than in its absence (0.02 vs. 0.005 cM). On the basis of the DSB repair model, NCOs analyzed in this study (class V) must have been initiated by DNA breaks on the a1::rdt-containing homolog. Consistent with MuDR's ability to interact with Mu1 but not rdt, the rate of the class V NCOs was unaffected by the presence (cross 2) or absence (cross 1) of MuDR. Class VI events (NCOs initiated from a1-mum2; Figure 1) would be colored and round. Because such kernels can be extremely difficult to distinguish from heavily spotted a1-mum2 kernels, and no germinal revertants of a1-mum2 were identified in a previous screen of 10,000 kernels (Lisch et al. 1995), the rates at which class VI events occur were not initially determined in this study. We subsequently attempted to isolate class VI events from the a1-mum2 source used in this study to determine the frequency at which MuDR-induced DNA breaks are repaired via conversion. Round kernels that appeared to be fully colored and that carried a1-s were selected from the progeny of a1-mum2 Sh2/a1 sh2 plants that carried MuDR and that had been crossed by an a1-s pollen source (a cross similar to cross 2). Only one excision event was confirmed from a population of ∼46,000 spotted kernels (data not shown). Therefore, the rate of reversion of a1-mum2 to A1′ (class VI events), i.e., ∼10−5, did not differ significantly from the rates of NCO from the a1::rdt chromosome (class V events) in the presence or absence of MuDR (Table 2). Hence, the increased rate of recombination that occurs in the presence of MuDR is due to an increased rate of COs.

TABLE 2.

Rates of intragenic recombination at thea1 locus

| Corrected no.

|

Rates (cM)a

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO + NCO | CO | NCO | Population size |

CO + NCO | COb | NCO | CO/NCOc | |

| Cross 1, without MuDR | 17 | 11 | 6 | 408,000 | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.003 ± 0.0009 | 1.8 |

| Cross 2, with MuDR | 47 | 40 | 7 | 530,800 | 0.02 ± 0.002 | 0.02 ± 0.002 | 0.003 ± 0.0008 | 5.7 |

Because only two of the four possible classes of recombination events were analyzed (III and V in Figure 1), the genetic distance associated with the 1.2-kb interval defined by the Mu1 and rdt insertion sites was calculated by doubling the rate of the corrected number of recombinants analyzed (see footnote c in Table 1). This calculation is based on the assumption that the frequencies of class III and IV CO events are equal and that the frequencies of class V and VI NCO events are equal. Because COs are reciprocal events it is reasonable to assume that the rates of class III and IV CO events are equal. Although it is not necessarily true that the rates of class V and VI NCOs are equal, the rate of class V events was doubled to allow comparisons between rates of COs and NCOs. Although the rates presented in this table cannot be used to draw conclusions regarding the rates of class VI NCOs, on the basis of a separate experiment, the rate of class VI NCOs in the presence of MuDR is low (∼10−5).

The homogeneity χ2 value for the rates of CO with and without MuDR (χ2 = 9.9, P = 0.002) indicated that the difference between these rates is significant. In contrast, the homogeneity χ2 test showed no significant difference between the rates of the NCO from cross 1 and cross 2 (χ2 = 0.04, P = 0.84).

CO/NCO ratios were calculated using only class III COs and class V NCOs (see footnote a).

Physical mapping of recombination breakpoints of COs and the 5′ (distal) endpoints of conversion tracts:

The conversion endpoints of 8 NCO events and the recombination breakpoints of 28 CO events were physically mapped. Because recombinants were selected on the basis of their colored, shrunken phenotypes, the breakpoints of all the COs and the distal endpoints of the conversion tracts must have resolved within the 1.2-kb interval defined by the Mu1 and rdt transposon insertion sites (Figure 2).

Digestion with PstI revealed that the distal endpoints of six of the eight conversion tracts map 5′ of the diagnostic PstI site that is polymorphic between a1-mum2 and a1::rdt. By virtue of the selection scheme used in the experiment, the conversion tracts cannot contain Mu1. Hence, the distal endpoints of these six conversion tracts must lie between the PstI site and the Mu1 insertion site. The 1.2-kb interval between the Mu1 and rdt insertion sites exhibits 20 polymorphisms between the a1-mum2 (GenBank accession no. AF347696) and a1::rdt alleles (GenBank accession no. AF072704). Regions containing the CO breakpoints or conversion tract endpoints associated with each of 36 A1′ alleles were PCR amplified and the purified PCR products were sequenced. The sequence derived from each recombinant A1′ allele was then compared to the sequences of the a1-mum2 and a1::rdt alleles. The switchpoint of sequence polymorphisms within each recombinant allele established, at the highest possible resolution, the position of each CO breakpoint or NCO conversion tract endpoint. The distributions of the CO breakpoints and the distal endpoints of the NCO conversion tracts are illustrated in Figure 2B. Whereas recombination hotspots in yeast are defined by regions of high DSB frequency, recombination hotspots in this and other plant studies are defined as regions with elevated rates of recombination resolution endpoints. The distal endpoints of 6 of 8 NCO events and the CO breakpoints of 21 of 28 crossover events mapped to the previously defined 377-bp recombination hotspot at the 5′ end of the a1 coding sequence (Xu et al. 1995).

Physical mapping of the 3′ (proximal) endpoints of conversion tracts:

On the basis of the genetic screen used to isolate recombination events, we believe that the proximal endpoints for all of the conversion tracts must have resolved proximal to the rdt insertion site. Only two DNA sequence polymorphisms exist between the a1-mum2 and a1::rdt alleles in the 1.6 kb proximal to the rdt insertion site (Figure 2A). One of these polymorphisms is a 32-bp insertion/deletion that is present in the a1-mum2 allele, but absent from the a1::rdt allele. By using an a1-mum2-specific primer (QZ1543) that anneals to the 32-bp polymorphic sequence in combination with a primer (XX907) that amplifies both a1-mum2 and a1::rdt alleles, it was possible to map the proximal endpoints of the conversion tracts relative to this 32-bp polymorphic site (Figure 2C). The ability of these primers to PCR amplify a given A1′ allele indicated that the conversion tract contained the 32-bp polymorphic sequence. Such a result would indicate that the proximal conversion tract endpoint was proximal to the 32-bp polymorphic site. The proximal conversion tract endpoints of four A1′ alleles derived from NCOs mapped proximal to the 32-bp polymorphic site. The 1059 bp proximal to this polymorphism are identical between the two a1 alleles. No a1-specific RFLPs were detected between a1-mum2 and a1::rdt that mapped between the 32-bp polymorphism and php10080 when the 1.0-kb SacI/EcoRI fragment from the a1-mum2 subclone pSC1.0 was used as a hybridization probe in a DNA gel blot experiment involving genomic DNA (data not shown). As a result, the proximal endpoints of these four conversion tracts could not be determined with higher precision.

A negative PCR result using primers QZ1543 and XX907 demonstrated that the proximal endpoint of an NCO was distal to the 32-bp polymorphic site. The proximal endpoints of four NCO A1′ alleles mapped distal to the 32-bp polymorphism. To map these proximal endpoints to higher resolution, the corresponding A1′ alleles were PCR amplified using primers XX907 and QZ1003 (Figure 2A). By comparing the sequences of the resulting 0.9-kb PCR product to the a1 parental alleles used to generate the A1′ alleles, the proximal endpoints were mapped at the highest possible resolution afforded by the sequence polymorphisms present between the parental alleles. The proximal endpoints of all four of these conversion tracts mapped to interval XXIII (Figure 2C). Although three of the conversion tracts are indistinguishable, they must have arisen via independent events because they were recovered from separate female parents in crosses 1 and 2.

Lengths of conversion tracts:

Because the positions of both the distal and the proximal endpoints of four conversion events were established, it was possible to calculate the sizes of the conversion tracts associated with each of the resulting A1′ alleles. As depicted in Figure 2C, three of the four conversion tracts were between 621 and 1318 bp in length. The fourth is between 31 and 683 bp. For the remaining four conversion events, although their distal endpoints were mapped at the highest possible precision, it was not possible to map their proximal endpoints because of a lack of polymorphisms between the parental a1 alleles (a1-mum2 and a1::rdt). Therefore, the absolute sizes of these four conversion tracts could not be determined. However, on the basis of the positions of the corresponding distal endpoints, the lengths of these conversion tracts must be in excess of 534 bp (1 allele), 1124 bp (1 allele), 1320 bp (1 allele), and 1603 bp (1 allele).

DISCUSSION

Physical characterization of NCO conversion tracts:

The average lengths of meiotic conversion tracts at the rosy locus of Drosophila melanogaster (Hilliker et al. 1994) and the rp49 locus of D. subobscura (Betran et al. 1997) are 352 and 122 bp, respectively. In contrast, the average tract lengths associated with Drosophila P-element excision were somewhat larger, i.e., ∼1400 bp (Gloor et al. 1991; Preston and Engels 1996). In yeast, the average meiotic conversion tract lengths range from 0.4 to 1.6 kb in a 9-kb interval (Borts and Haber 1989). Even so, longer conversion tracts of 9 and 12 kb have also been observed in yeast (Borts et al. 2000). Conversion tracts >5 kb have also been observed in Neurospora (Yeadon and Catcheside 1998). Few plant conversion tracts have been characterized. In maize, two a1 conversion tracts were in excess of 621 and 815 bp (Xu et al. 1995) and two bz1 conversion tracts were between 965 and 1165 bp and between 1.1 and 1.5 kb (Dooner and Martinez-Ferez 1997b). The conversion tracts of two NCO-like events isolated from the maize Kn1-O tandem duplication (Mathern and Hake 1997) are 1.7 and 3 kb. Yao et al. (2002) identified two putative NCOs from the maize a1-sh2 interval that have conversion tracts that are at least 17 kb.

The eight conversion tracts characterized in this study (crosses 1 and 2) ranged in size from >31 bp to >1603 bp. These NCO events resulted from conversion of the rdt insertion and its surrounding sequences and were therefore initiated by DSBs on the a1::rdt-containing chromosome. Conversion tracts on the a1::rdt-containing chromosome that extended 5′ of the Mu1 insertion site would not have been recovered.

The single revertant allele isolated from a1-mum2 in this study exhibited 100% identity to the wild-type progenitor of a1-mum2 (i.e., A1-LC). This revertant may therefore have arisen via a class VI NCO event (Figure 1) within the interval 51 bp upstream and 165 bp downstream of the Mu1 insertion site that lacks polymorphisms between the parental alleles of crosses 1 and 2. This would be consistent with the finding that in mice and yeast, gene conversion tracts can be <100 bp (Sweetser et al. 1994; Elliott et al. 1998; Palmer et al. 2003).

Factors affecting CO/NCO ratios:

In yeast heterozygotes, the presence of only a few nucleotide polymorphisms can drastically affect the frequencies at which COs (Borts and Haber 1987; Borts et al. 1990) and NCOs (Chen and Jinks-Robertson 1999; Nickoloff et al. 1999) are recovered. For example, 0.09% heterology between alleles at the MAT loci in yeast reduced COs by twofold and increased the rate of NCOs by threefold (Borts et al. 1990). Similarly, in the maize bz1 gene, the degree of sequence similarity between the parental alleles affects the CO/NCO ratio (Dooner 2002). In Dooner's study the CO/NCO ratio observed between bz1 “heteroalleles” was >20. In the current study, the CO/NCO ratio observed in plants that lacked MuDR was 1.8. This dramatic difference in the CO/NCO ratio between the two studies cannot be attributed to differences in the degree of DNA sequence polymorphism, because Dooner's heteroalleles exhibited approximately the same degree of DNA sequence polymorphism (1.5%) as the parental a1 alleles used in the current study (1.8%). Instead, the ∼10-fold difference in the CO/NCO ratios between the two studies could be a consequence of locus-specific differences in the relative rates of conversions and crossovers or differences caused by genetic background. Although it is not possible to exclude locus-specific effects, this study does establish that CO/NCO ratios can be influenced by the differences in genetic background. Specifically, this study establishes that MuDR affects CO/NCO ratios. For example, the CO/NCO ratios differ by more than threefold between crosses 1 and 2 (compare CO/NCO ratios, Table 2) for which the genetic backgrounds are identical except for the absence (cross 1) or presence (cross 2) of MuDR. We cannot exclude the possibility that the relative impacts of MuDR on rates of COs and NCOs may differ depending upon the level of sequence heterology present in a heterozygote. For example, it is possible that in heterozygotes exhibiting a degree of heterology lower than that present in crosses 1 and 2, MuDR might increase the rate of NCOs. This, however, seems unlikely given that reversions of Mu-induced alleles of all loci studied are quite rare in diverse genetic backgrounds, which would be expected to exhibit varying levels of heterology at the target loci.

MuDR increases the rate of COs at a1:

According to the most widely accepted recombination models (Szostak et al. 1983; Sun et al. 1991; Allers and Lichten 2001), which are well supported by data from yeast, meiotic recombination is initiated by DSBs and the subsequent repair and resolution of these DSBs results in COs or NCOs. Although in plants the mechanisms underlying meiotic recombination are not as well understood, it is thought that they are at least similar to those that occur in yeast. Support for this view comes from the isolation of plant homologs of many of the yeast genes involved in DSB processing and meiotic recombination (reviewed in Bhatt et al. 2001; Schwarzacher 2003). Also, agents that introduce DSBs into plant chromosomes increase rates of mitotic recombination and intrachromosomal recombination.

It has not yet, however, been determined in plants whether the stimulation of DNA breaks increases the rate of homologous meiotic recombination. To address this question, recombinants were isolated from a1-mum2/a1::rdt heterozygotes that carried or did not carry MuDR. MuDR encodes a transposase (Chomet et al. 1991; Hershberger et al. 1991; Qin et al. 1991; Hsia and Schnable 1996) required for the transposition of Mu elements. This transposition must involve some type of DNA breaks. The recovery of chromosomes that contain deletions of sequences adjacent to Mu elements and internally deleted Mu elements is consistent with the existence of MuDR-catalyzed DNA breaks in the vicinity of Mu elements (Levy et al. 1989; Levy and Walbot 1991; Lisch et al. 1995; Hsia and Schnable 1996; Asakura et al. 2002; Kim and Walbot 2003). Because the mechanism by which MuDR catalyzes transposition has not been determined, these MuDR-generated breaks could be either DSBs or single-strand nicks. It has long been assumed that these breaks were DSBs, but recent evidence suggests that single-strand nicks can stimulate homologous recombination in the V(D)J regions of immunoglobulin genes (Lee et al. 2004). Hence, MuDR-generated single-strand nicks could affect recombination directly or could be converted into DSBs during DNA replication (Kuzminov 2001). Alternatively, MuDR may directly catalyze DSB formation.

Regardless of the mechanism by which MuDR generates DNA breaks, crosses harboring MuDR would be expected to have an increased rate of breaks in the vicinity of the Mu1 insertion in the a1-mum2 allele. At least three processes could repair MuDR-induced DNA breaks at a1-mum2. These include COs between the two homologs (class III and IV events, Figure 1); conversion of the Mu1-containing homolog, using as template the homolog that does not contain Mu1 (class VI NCO events, Figure 1); or DSB repair, using as template the sister chromatid. This latter process would not generate recombinant chromosomes and would in fact regenerate the parental a1-mum2 allele or either internal or adjacent deletions of Mu1 if gap repair is interrupted (Lisch et al. 1995; Hsia and Schnable 1996; Asakura et al. 2002; Kim and Walbot 2003).

MuDR is required for the transposition of Mu transposons, a process that requires the introduction of DNA breaks. According to accepted recombination models, COs are also initiated by DNA breaks. Hence, we interpret our observation that plants that carry MuDR exhibit four times more class III COs (Figure 1) than do plants that do not carry MuDR (Table 2) to indicate that during meiosis at least some MuDR-induced DNA breaks are repaired via the CO pathway. Hence, our results strongly suggest that DNA breaks stimulate meiotic COs in plants.

Although MuDR stimulates meiotic COs, the Ac transposon does not (Dooner and Martinez-Ferez 1997a). This suggests that Ac-induced DSBs are separated temporally or spatially from meiotic recombination (Dooner and Martinez-Ferez 1997a) or that Ac-induced DSBs are repaired by another pathway, for example via the formation of hairpins followed by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) repair at sites of microhomology (Weil and Kunze 2000; Yu et al. 2004).

We cannot rule out the possibility that the increased rates of CO observed in this study are not a direct consequence of an increased rate of breaks at Mu1 but are instead a consequence of potential changes in the chromatin architecture at a1-mum2 that occur in the presence of MuDR. Even if the transposase per se is not generating breaks at the Mu1 insertion site, the transposase must at least be creating a local environment that is more conducive to the formation of endogenous DNA breaks. If this alternative model is correct, a MuDR-encoded transposase that can bind to Mu terminal inverted repeats, but that cannot catalyze transposition, should increase the rate of recombination in the vicinity of a Mu insertion. Regardless of whether the breaks are caused directly or indirectly by MuDR, it is clear that MuDR stimulates the formation of DNA breaks at the a1-mum2 allele, resulting in increased rates of meiotic CO.

Does MuDR affect the rate of gene conversion?

There are two classes of NCOs (classes V and VI, Figure 1). Although MuDR increased the rate of COs it did not increase the rate of class V NCOs in the a1-mum2/a1::rdt heterozygote. This is as expected because MuDR would not be predicted to interact with a1::rdt. In contrast, the existence of somatic excision events in MuDR-containing stocks demonstrates that MuDR interacts (directly or indirectly) with Mu insertions. Even so, germinal reverants of Mu-insertion alleles (including class VI NCOs) are rare (reviewed in Bennetzen 1996; Lisch 2002; Walbot and Rudenko 2002); the frequencies of germinal revertants from the bronze locus are 8 × 10−5 (Brown et al. 1989b) and between 4.9 × 10−6 and 2.3 × 10−3 (Schnable et al. 1989). Consistent with these results, we and others (Lisch et al. 1995) have shown that the rate of class VI NCOs at a1-mum2 is low. It is puzzling that in this heterozygote, although MuDR increases the rate of CO fourfold, the rate of class VI NCOs is low in the presence of MuDR.

In yeast, several meiotic mutants that affect SEI and DHJ formation drastically reduce the frequency of COs but not NCOs. This suggests that recombination outcomes (CO vs. NCO repair) are determined prior to stable strand exchange (i.e., SEI; Borner et al. 2004). If this is also true in plants, the MuDR-generated breaks might be designated prior to strand exchange to be repaired by the CO pathway. In V(D)J site-specific recombination, the RAG recombinases act as molecular shepherds that allow repair of the RAG-generated DSB by the NHEJ machinery and not other repair pathways (Lee et al. 2004). Similarly, during meiosis the MuDR transposase and/or protein(s) involved in the meiotic recombination machinery may remain bound to the MuDR-generated DNA breaks and thereby channel repairs to the CO pathway. It is also possible that some repairs of MuDR-induced DNA breaks could be channeled to pathways that were not detected in this study because they do not yield COs or germinal revertants (e.g., repair using the sister chromatid as template or NHEJ). The high somatic and low germinal reversion rates observed in the Mu system could be explained if these “molecular shepherds” differ between the mitotic and meiotic cellular programs.

MuDR does not affect the distribution of recombination breakpoints:

Insertion/deletion polymorphisms (IDPs) and transposon insertions suppress recombination in nearby regions of the bz1 locus (Dooner and Martinez-Ferez 1997b). By doing so these IDPs change the distribution of recombination breakpoints across the bz1 locus, creating apparent recombination hotspots. In contrast, the distribution of recombination breakpoints across the a1 gene is not affected by the Mu1 insertion at position −97 in a1-mum2 (Xu et al. 1995; Yao et al. 2002). Hence, the recombination hotspot reported by Xu et al. (1995) is not a consequence of the Mu1 insertion in one of the parental alleles used by that study.

Although the rates of CO at a1 increase fourfold in the presence of MuDR, the distribution of recombination breakpoints is not altered by MuDR; 19 of the 24 characterized breakpoints cluster in the 377-bp hotspot at the 5′ end of the a1 gene (Figure 2B) previously identified in stocks that lack MuDR (Xu et al. 1995). Hence, the COs that are apparently initiated by MuDR-induced breaks at the Mu1 insertion at −97 resolve at the same positions within a1 as do the COs that are initiated by the DSBs that form in the absence of MuDR. COs resolve in this same hotspot even in an A1 allele that does not contain a Mu1 insertion (Yao et al. 2002). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the DSBs that initiate recombination in nonmutant a1 alleles occur in the vicinity of position −97. Even though the relationship between the positions of DSB hotspots and recombination hotspots has not yet been studied in plants, the observation that most a1 recombinants mapped within 700 bp of the Mu1 insertion site is consistent with the observation that most recombination hotspots in budding yeast are located within 1 or 2 kb of a DSB hotspot (Smith 2001).

MuDR is active in meiotic cells:

Although the Mu transposase mudrA and mudrB transcripts are highly expressed in mature pollen and mudrB promoter::reporter constructs are expressed at levels 20-fold higher in pollen than in leaves (Raizada et al. 2001a), to date, there has not been conclusive evidence that the MuDR transposase is active and functions during meiosis. Instead, germinally transmissible Mu insertions could arise via late somatic excision in premeiotic cells (reviewed in Walbot and Rudenko 2002) or via postmeiotic transposition (Robertson and Stinard 1993). In contrast, by demonstrating that MuDR increases rates of meiotic recombination at a1-mum2 fourfold, the current study provides the first direct evidence that MuDR is active during meiosis.

Evolutionary implications:

This study extends our understanding of how transposons can alter recombination rates. The insertion of a nonautonomous transposon into a gene typically reduces the rate of intragenic recombination. For example, the insertion of a Mu1 transposon into the A1-LC allele (which generated a1-mum2) reduced the rate of recombination approximately twofold (Xu et al. 1995). In contrast and as revealed by this study, if a Mu-insertion allele is present in a genome that contains an active copy of MuDR, the rate of intragenic recombination can actually be higher (twofold in this case) than that of the original allele that lacked a transposon insertion. Because a variety of plant DNA transposons have an affinity for inserting into genes (Bureau et al. 1996; Raizada et al. 2001b; Jiang et al. 2004) and intragenic recombination can generate new alleles, their ability to alter rates of intragenic recombination could have significant evolutionary implications.

APPENDIX.

Positions of the recombination breakpoints associated with theA1′ alleles isolated from crosses 1 and 2

| Allelea | Cross | Position of breakpoint/5′ endpointb |

Position of 3′ endpoint |

Type of recombination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 94B 129 | 2 | NDc | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 131 | 2 | VII | XXIII | Gene conversion |

| 94B 132 | 2 | XXI | XXIII | Gene conversion |

| 94B 133 | 2 | V | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 135 | 2 | ND | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 136 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 139 | 2 | XIII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 140 | 2 | I | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 141 | 2 | I | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 142 | 2 | V | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 143 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 145 | 2 | ND | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 146 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 149 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 150 | 2 | V | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 151 | 2 | V | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 152 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 153 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 154 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 156 | 2 | I | 3′ of XXIII | Gene conversion |

| 94B 158 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 161 | 2 | V | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 164 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 166 | 2 | XIII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 168 | 2 | XXI | 3′ of XXIII | Gene conversion |

| 94B 169 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 170 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 173 | 2 | V | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 176 | 2 | V | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 177 | 2 | VII | XXIII | Gene conversion |

| 94B 179 | 2 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 185 | 2 | XIII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 188 | 1 | II | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 190 | 1 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 192 | 1 | VII | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 195 | 1 | VII | 3′ of XXIII | Gene conversion |

| 94B 198 | 1 | V | 3′ of XXIII | Gene conversion |

| 94B 199 | 1 | XV | NA | Crossover |

| 94B 200 | 1 | VII | XXIII | Gene conversion |

| 94B 202 | 1 | ND | NA | Crossover |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by competitive grants from the United States Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Program to P.S.S. and B.J.N. (9701407 and 9901579) and to P.S.S. (0101869 and 0300940). This is journal paper no. J-19273 of the Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station, Ames, Iowa, project nos. 3334, 3485, and 6502, supported by Hatch Act and State of Iowa funds.

References

- Allers, T., and M. Lichten, 2001. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell 106: 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura, N., C. Nakamura, T. Ishii, Y. Kasai and S. Yoshida, 2002. A transcriptionally active maize MuDR-like transposable element in rice and its relatives. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athma, P., and T. Peterson, 1991. Ac induces homologous recombination at the maize P locus. Genetics 128: 163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen, J. L., 1996. The Mutator transposable element system of maize. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 204: 195–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betran, E., J. Rozas, A. Navarro and A. Barbadilla, 1997. The estimation of the number and the length distribution of gene conversion tracts from population DNA sequence data. Genetics 146: 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, A. M., C. Canales and H. G. Dickinson, 2001. Plant meiosis: the means to 1N. Trends Plant Sci. 6: 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner, G. V., N. Kleckner and N. Hunter, 2004. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell 117: 29–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borts, R. H., and J. E. Haber, 1987. Meiotic recombination in yeast: alteration by multiple heterozygosities. Science 237: 1459–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borts, R. H., and J. E. Haber, 1989. Length and distribution of meiotic gene conversion tracts and crossovers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 123: 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borts, R. H., W. Y. Leung, W. Kramer, B. Kramer, M. Williamson et al., 1990. Mismatch repair-induced meiotic recombination requires the pms1 gene product. Genetics 124: 573–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borts, R. H., S. R. Chambers and M. F. Abdullah, 2000. The many faces of mismatch repair in meiosis. Mutat. Res. 451: 129–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. J., M. G. Mattes, C. O'Reilly and N. S. Shepherd, 1989. a Molecular characterization of rDt, a maize transposon of the “Dotted” controlling element system. Mol. Gen. Genet. 215: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W. E., D. S. Robertson and J. L. Bennetzen, 1989. b Molecular analysis of multiple Mutator-derived alleles of the Bronze locus of maize. Genetics 122: 439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, T. E., P. C. Ronald and S. R. Wessler, 1996. A computer-based systematic survey reveals the predominance of small inverted-repeat elements in wild-type rice genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 8524–8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W., and S. Jinks-Robertson, 1999. The role of the mismatch repair machinery in regulating mitotic and meiotic recombination between diverged sequences in yeast. Genetics 151: 1299–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiurazzi, M., A. Ray, J. F. Viret, R. Perera, X. H. Wang et al., 1996. Enhancement of somatic intrachromosomal homologous recombination in Arabidopsis by the HO endonuclease. Plant Cell 8: 2057–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomet, P., D. Lisch, K. J. Hardeman, V. L. Chandler and M. Freeling, 1991. Identification of a regulatory transposon that controls the Mutator transposable element system in maize. Genetics 129: 261–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, Q., M. Russell, D. E. Birch, J. Raymond and W. Bloch, 1992. Prevention of pre-PCR mis-priming and primer dimerization improves low-copy-number amplifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 20: 1717–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civardi, L., Y. Xia, K. J. Edwards, P. S. Schnable and B. J. Nikolau, 1994. The relationship between genetic and physical distances in the cloned a1-sh2 interval of the Zea mays L. genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 8268–8272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, I., and C. S. Newlon, 1994. Meiosis-specific formation of joint DNA molecules containing sequences from homologous chromosomes. Cell 76: 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Massy, B., and A. Nicolas, 1993. The control in cis of the position and the amount of the ARG4 meiotic double-strand break of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 12: 1459–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detloff, P., M. A. White and T. D. Petes, 1992. Analysis of a gene conversion gradient at the HIS4 locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132: 113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooner, H. K., 1986. Genetic fine structure of the bronze locus in maize. Genetics 113: 1021–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooner, H. K., 2002. Extensive interallelic polymorphisms drive meiotic recombination into a crossover pathway. Plant Cell 14: 1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooner, H. K., and I. M. Martinez-Ferez, 1997. a Germinal excisions of the maize transposon activator do not stimulate meiotic recombination or homology-dependent repair at the bz locus. Genetics 147: 1923–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooner, H. K., and I. M. Martinez-Ferez, 1997. b Recombination occurs uniformly within the bronze gene, a meiotic recombination hotspot in the maize genome. Plant Cell 9: 1633–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston, W. B., M. Alleman and J. L. Kermicle, 1995. Molecular organization and germinal instability of R-stippled maize. Genetics 141: 347–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, B., C. Richardson, J. Winderbaum, J. A. Nickoloff and M. Jasin, 1998. Gene conversion tracts from double-strand break repair in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q., F. Xu and T. D. Petes, 1995. Meiosis-specific double-strand DNA breaks at the HIS4 recombination hot spot in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: control in cis and trans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 1679–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Game, J. C., 1992. Pulsed-field gel analysis of the pattern of DNA double-strand breaks in the Saccharomyces genome during meiosis. Dev. Genet. 13: 485–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerton, J. L., J. DeRisi, R. Shroff, M. Lichten, P. O. Brown et al., 2000. Inaugural article: global mapping of meiotic recombination hotspots and coldspots in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 11383–11390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor, G. B., N. A. Nassif, D. M. Johnson-Schlitz, C. R. Preston and W. R. Engels, 1991. Targeted gene replacement in Drosophila via P element-induced gap repair. Science 253: 1110–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyon, C., and M. Lichten, 1993. Timing of molecular events in meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: stable heteroduplex DNA is formed late in meiotic prophase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger, R. J., C. A. Warren and V. Walbot, 1991. Mutator activity in maize correlates with the presence and expression of the Mu transposable element Mu9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 10198–10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliker, A. J., G. Harauz, A. G. Reaume, M. Gray, S. H. Clark et al., 1994. Meiotic gene conversion tract length distribution within the rosy locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 137: 1019–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, R., 1964. A mechanism for gene conversion in fungi. Genet. Res. 78: 282–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia, A. P., and P. S. Schnable, 1996. DNA sequence analyses support the role of interrupted gap repair in the origin of internal deletions of the maize transposon, MuDR. Genetics 142: 603–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, N., and N. Kleckner, 2001. The single-end invasion: an asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to double-Holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell 106: 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N., C. Feschotte, X. Zhang and S. R. Wessler, 2004. Using rice to understand the origin and amplification of miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs). Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7: 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. H., and V. Walbot, 2003. Deletion derivatives of the MuDR regulatory transposon of maize encode antisense transcripts but are not dominant-negative regulators of mutator activities. Plant Cell 15: 2430–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzminov, A., 2001. Single-strand interruptions in replicating chromosomes cause double-strand breaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 8241–8246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G. S., M. B. Neiditch, S. S. Salus and D. B. Roth, 2004. RAG proteins shepherd double-strand breaks to a specific pathway, suppressing error-prone repair, but RAG nicking initiates homologous recombination. Cell 117: 171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M., N. Sharopova, W. D. Beavis, D. Grant, M. Katt et al., 2002. Expanding the genetic map of maize with the intermated B73 × Mo17 (IBM) population. Plant Mol. Biol. 48: 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. A., and V. Walbot, 1991. Molecular analysis of the loss of somatic instability in the bz2::mu1 allele of maize. Mol. Gen. Genet. 229: 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. A., A. B. Britt, K. R. Luehrsen, V. L. Chandler, C. Warren et al., 1989. Developmental and genetic aspects of Mutator excision in maize. Dev. Genet. 10: 520–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., J. P. Bernot, C. Illingworth, W. Lison, K. M. Bernot et al., 2001. Gene conversion within regulatory sequences generates maize r alleles with altered gene expression. Genetics 159: 1727–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichten, M., and A. S. Goldman, 1995. Meiotic recombination hotspots. Annu. Rev. Genet. 29: 423–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichten, M., C. Goyon, N. P. Schultes, D. Treco, J. W. Szostak et al., 1990. Detection of heteroduplex DNA molecules among the products of Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87: 7653–7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisch, D., 2002. Mutator transposons. Trends Plant Sci. 7: 498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisch, D., P. Chomet and M. Freeling, 1995. Genetic characterization of the Mutator system in maize: behavior and regulation of Mu transposons in a minimal line. Genetics 139: 1777–1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., T. C. Wu and M. Lichten, 1995. The location and structure of double-strand DNA breaks induced during yeast meiosis: evidence for a covalently linked DNA-protein intermediate. EMBO J. 14: 4599–4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, B., J. Mathern and S. Hake, 1992. Active Mutator elements suppress the knotted phenotype and increase recombination at the Kn1-O tandem duplication. Genetics 132: 813–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathern, J., and S. Hake, 1997. Mu element-generated gene conversions in maize attenuate the dominant knotted phenotype. Genetics 147: 305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag, D. K., and T. D. Petes, 1993. Physical detection of heteroduplexes during meiotic recombination in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 2324–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton, C. R., A. Graham, L. E. Heptinstall, S. J. Powell, C. Summers et al., 1989. Analysis of any point mutation in DNA. The amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS). Nucleic Acids Res. 17: 2503–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff, J. A., D. B. Sweetser, J. A. Clikeman, G. J. Khalsa and S. L. Wheeler, 1999. Multiple heterologies increase mitotic double-strand break-induced allelic gene conversion tract lengths in yeast. Genetics 153: 665–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly, C., N. S. Shepherd, A. Pereira, Z. Schwarz-Sommer, I. Bertram et al., 1985. Molecular cloning of the a1 locus of Zea mays using the transposable elements En and Mu1. EMBO J. 4: 877–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, S., E. Schildkraut, R. Lazarin, J. Nguyen and J. A. Nickoloff, 2003. Gene conversion tracts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae can be extremely short and highly directional. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 1164–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, G. I., K. M. Kubo, T. Shroyer and V. L. Chandler, 1995. Sequences required for paramutation of the maize b gene map to a region containing the promoter and upstream sequences. Genetics 140: 1389–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston, C. R., and W. R. Engels, 1996. P-element-induced male recombination and gene conversion in Drosophila. Genetics 144: 1611–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta, H., and B. Hohn, 1996. From centiMorgans to base pairs: homologous recombination in plants. Trends Genet. 1: 340–348. [Google Scholar]

- Puchta, H., B. Dujon and B. Hohn, 1993. Homologous recombination in plant cells is enhanced by in vivo induction of double strand breaks into DNA by a site-specific endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 21: 5034–5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta, H., B. Dujon and B. Hohn, 1996. Two different but related mechanisms are used in plants for the repair of genomic double-strand breaks by homologous recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 5055–5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, M. M., D. S. Robertson and A. H. Ellingboe, 1991. Cloning of the Mutator transposable element MuA2, a putative regulator of somatic mutability of the a1-Mum2 allele in maize. Genetics 129: 845–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizada, M. N., M. I. Benito and V. Walbot, 2001. a The MuDR transposon terminal inverted repeat contains a complex plant promoter directing distinct somatic and germinal programs. Plant J. 25: 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizada, M. N., G. L. Nan and V. Walbot, 2001. b Somatic and germinal mobility of the RescueMu transposon in transgenic maize. Plant Cell 13: 1587–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, M. A., 1976. The repair of double-strand breaks in DNA; a model involving recombination. J. Theor. Biol. 59: 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, D. S., and P. S. Stinard, 1993. Evidence for Mu activity in the male and female gametophytes of maize. Maydica 38: 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Schnable, P. S., and P. A. Peterson, 1986. Distribution of genetically active Cy elements among diverse maize lines. Maydica 31: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Schnable, P. S., P. A. Peterson and H. Saedler, 1989. The bz-rcy allele of the Cy transposable element system of Zea mays contains a Mu-like element insertion. Mol. Gen. Genet. 217: 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable, P. S., A. P. Hsia and B. J. Nikolau, 1998. Genetic recombination in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultes, N. P., and J. W. Szostak, 1990. Decreasing gradients of gene conversion on both sides of the initiation site for meiotic recombination at the ARG4 locus in yeast. Genetics 126: 813–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha, A., and N. Kleckner, 1994. Identification of joint molecules that form frequently between homologs but rarely between sister chromatids during yeast meiosis. Cell 76: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha, A., and N. Kleckner, 1995. Identification of double Holliday junctions as intermediates in meiotic recombination. Cell 83: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzacher, T., 2003. Meiosis, recombination and chromosomes: a review of gene isolation and fluorescent in situ hybridization data in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 54: 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G. R., 2001. Homologous recombination near and far from DNA breaks: alternative roles and contrasting views. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35: 243–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinard, P. S., D. S. Robertson and P. S. Schnable, 1993. Genetic isolation, cloning, and analysis of a mutator-induced, dominant antimorph of the maize amylose extender1 locus. Plant Cell 5: 1555–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H., D. Treco, N. P. Schultes and J. W. Szostak, 1989. Double-strand breaks at an initiation site for meiotic gene conversion. Nature 338: 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H., D. Treco and J. W. Szostak, 1991. Extensive 3′-overhanging, single-stranded DNA associated with the meiosis-specific double-strand breaks at the ARG4 recombination initiation site. Cell 64: 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser, D. B., H. Hough, J. F. Whelden, M. Arbuckle and J. A. Nickoloff, 1994. Fine-resolution mapping of spontaneous and double-strand break-induced gene conversion tracts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals reversible mitotic conversion polarity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 3863–3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak, J. W., T. L. Orr-Weaver, R. J. Rothstein and F. W. Stahl, 1983. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell 33: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walbot, V., and G. N. Rudenko, 2002 MuDR/Mu transposable elements of maize, pp. 533–564 in Mobile DNA II, edited by N. L. Craig, R. Craigie, M. Gellert and A. M. Lambowitz. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Weil, C. F., and R. Kunze, 2000. Transposition of maize Ac/Ds transposable elements in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Genet. 26: 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J. H., K. Lusnak and S. Fogel, 1985. Mismatch-specific post-meiotic segregation frequency in yeast suggests a heteroduplex recombination intermediate. Nature 315: 350–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y. L., and T. Peterson, 2000. Intrachromosomal homologous recombination in Arabidopsis induced by a maize transposon. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y. L., X. Li and T. Peterson, 2000. Ac insertion site affects the frequency of transposon-induced homologous recombination at the maize p1 locus. Genetics 156: 2007–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X., A. P. Hsia, L. Zhang, B. J. Nikolau and P. S. Schnable, 1995. Meiotic recombination break points resolve at high rates at the 5′ end of a maize coding sequence. Plant Cell 7: 2151–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H., Q. Zhou, J. Li, H. Smith, M. Yandeau et al., 2002. Molecular characterization of meiotic recombination across the 140-kb multigenic a1-sh2 interval of maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 6157–6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeadon, P. J., and D. E. Catcheside, 1998. Long, interrupted conversion tracts initiated by cog in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 148: 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J., K. Marshall, M. Yamaguchi, J. E. Haber and C. F. Weil, 2004. Microhomology-dependent end joining and repair of transposon-induced DNA hairpins by host factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 1351–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenvirth, D., T. Arbel, A. Sherman, M. Goldway, S. Klein et al., 1992. Multiple sites for double-strand breaks in whole meiotic chromosomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 11: 3441–3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]