Abstract

Repeated measurements and mixed-effects models were used to analyze the effects of an intensive long-term street-level police intervention on syringe exchange program use. Utilization data for 9 months before and after the beginning of the intervention were analyzed. Use fell across all categories and time periods studied, with significant declines in use among total participants, male participants, and Black participants. Declines in use among Black and male participants were much more pronounced than decreases among White and female participants.

Of the 1127 AIDS cases reported to the Philadelphia, Pa, Department of Health during 2001, approximately 39% were attributed to injection drug use, a higher percentage than for any other risk factor and 19% higher than the national average.1,2 Syringe exchange programs have been associated with decreased incidence of blood-borne disease infection and risky syringe-related behaviors among injection drug users (IDUs).3–6 A legal syringe exchange program has operated in Philadelphia since 1992.7 For most of the population served by the syringe exchange program, it is the only accessible source for sterile syringes.

On May 1, 2002, Philadelphia launched an intensive long-term street-level policing initiative that deployed uniformed officers to occupy targeted city corners around the clock to disrupt open-air drug markets. The police department targeted these corners because of the amount and severity of drug violence present.8 Many of these targeted corners were near syringe exchange program sites, and many clients likely passed by these corners while traveling to the syringe exchange program. The syringe exchange program did not change locations, times, or staffing patterns during the study period (C. Cook, MSS, MLSP, written communication, January 23, 2003).

The operation represents a change in police tactics from previous antidrug initiatives, by decreasing arrests in favor of “deterrence and dispersal” tactics to disrupt drug markets and by maintaining a persistent heavy police presence.8 Narcotics arrests substantially decreased after the operation began, despite greatly increased police activity.8 However, many instances of police harassment of syringe exchange program users have been reported by exchange staff since the operation began, and on at least 1 occasion, a syringe exchange program user was arrested for possessing syringes procured at the syringe exchange program. Plans are to continue this long-term operation as long as funding continues.

Research has long shown that IDUs are sensitive to police activity while making decisions about injection.9–11 Concern about arrest or search may lead to failure to seek and carry sterile syringes, as well as more rapid and less hygienic injection, and may deter uptake of health and preventive services.12–17 Differences in exposure to street-level drug policing may contribute to sharp differences in the rate of injection-related HIV in Black and White people in the United States.18

METHODS

Data were drawn from Philadelphia’s syringe exchange program, which collects use and demographic information from all participants. Aggregate changes in syringe exchange program use were examined for periods of 3 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months before and after the initiation of the police intervention, as measured by number of participants appearing, number of syringes dispensed, and number of Black and male participants appearing. For comparison, these procedures also were performed on prior year data for all periods studied.

We then used a mixed-effects model for each response.19 This model used the 6-week mean response around each of the time points. Comparison of the 9-month periods before and after the initiation of the intervention required the use of linear and quadratic time effects and their interactions with the 2-level period factor. These models were summarized by considering contrasts between corresponding time points from the before and after periods. In these analyses, a P value of .05 or lower was considered significant.

RESULTS

Syringe exchange program use—as measured by aggregate totals—declined across all measurement categories and time periods studied following the policing intervention. During all periods measured, use by Black individuals declined at more than twice the rate of White individuals, and use by males declined at or near twice the rate of females. By contrast, utilization trends in the prior year periods were nearly stable (Table 1 ▶).

TABLE 1—

Change in Philadelphia Syringe Exchange Program Use Measures Before and After Police Intervention

| Total Visits | Black Visits | White Visits | Male Visits | Female Visits | |

| Comparison period | |||||

| 3 wks before vs 3 wks after | |||||

| Total change | −340 | −196 | −117 | −286 | −35 |

| Mean change | −113 | −65 | −39 | −95 | −12 |

| % Change | −23.60 | −33.40 | −16.41 | −26.21 | −11.59 |

| 3 mos before vs 3 mos after | |||||

| Total change | −896 | −639 | −305 | −1071 | −148 |

| Mean change | −69 | −49 | −23 | −82 | −11 |

| % Change | −14.30 | −25.24 | −9.67 | −21.83 | −10.86 |

| 6 mos before vs 6 mos after | |||||

| Total change | −1759 | −1285 | −557 | −2292 | −341 |

| Mean change | −68 | −49 | −21 | −88 | −13 |

| % Change | −13.73 | −24.56 | −8.74 | −22.27 | −11.61 |

| 9 mos before vs 9 mos after | |||||

| Total change | −3539 | −2428 | −1276 | −3119 | −559 |

| Mean change | −91 | −62 | −33 | −80 | −14 |

| % Change | −18.10 | −30.10 | −13.02 | −21.09 | −13.03 |

| Previous year period | |||||

| 3 wks before vs 3 wks after | |||||

| Total change | 40 | 16 | 12 | 48 | −6 |

| Mean change | 13 | 5 | 4 | 6 | −2 |

| % Change | 2.87 | 2.75 | 1.70 | 4.70 | 1.06 |

| 3 mos before vs 3 mos after | |||||

| Total change | 110 | 141 | −33 | 99 | 23 |

| Mean change | 8 | 11 | −3 | 7 | 2 |

| % Change | 1.92 | 6.20 | −3.64 | 2.30 | 1.70 |

| 6 mos before vs 6 mos after | |||||

| Total change | 474 | −9 | 307 | 338 | 109 |

| Mean change | 18 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 4 |

| % Change | 4.00 | −0.17 | 5.26 | 3.63 | 4.03 |

| 9 mos before vs 9 mos after | |||||

| Total change | 1347 | −346 | 586 | 677 | 164 |

| Mean change | 34 | −9 | 16 | 17 | 4 |

| % Change | 7.39 | −4.07 | 6.78 | 3.76 | 3.86 |

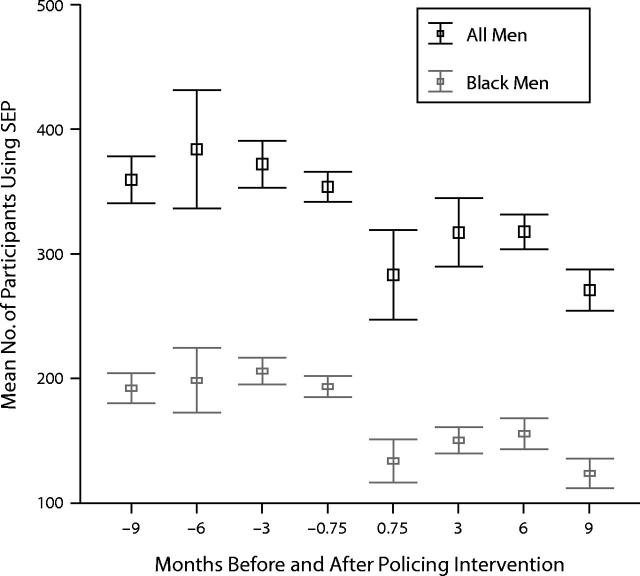

The mixed-effects model found significant (P < .001) declines in total visits, Black visits, and male visits at 3, 6, and 9 months post-implementation. Three-week comparisons were significant for number of visits by Black participants (P = .003) and by males (P = .02). Figure 1 ▶ shows the observed 6-week means around each time point for these categories.

FIGURE 1—

Syringe exchange program (SEP) use of selected groups: 6-week means around studied time points. Error bars show SE.

DISCUSSION

By most accounts, the policing intervention successfully reduced the prevalence of open drug sales on the targeted corners.20–22 Our findings suggested that this benefit came with a cost: the operation was significantly associated with a reduction in the use of Philadelphia’s syringe exchange programs, especially among Black and male participants. Such a reduction in syringe exchange program use can be expected to lead to increased sharing and reusing of syringes, with an attendant increase in blood-borne infectious disease incidence among IDUs who formerly used syringe exchange programs.23

The operation relied on greatly increased police presence, rather than arrests, to disrupt settled patterns of drug sale and use. Decreasing arrests as a tool for controlling drug abuse has been suggested as an important step in developing a public health approach to the drug problem.24 However, our findings suggested that police practices other than arrests also can increase risks for IDUs.

The disproportionate decline in the number of Black individuals and males presenting to syringe exchange programs heightens concern that law enforcement practices contributed to inequalities in access to HIV prevention resources between Black and White individuals, perhaps by focusing deterrence efforts on Black males. This is especially worrisome because Black individuals are more likely than the general population both to be affected by law enforcement activity and to contract HIV.1,25–29

Data identifying the specific corners at which officers were posted were not available, which made it impossible to test for a spatial relation between operation sites and syringe exchange program use.

Efforts to reduce the health consequences of drug use need not conflict with the goals of reducing street crime and enhancing public order.30–34 Integration of law enforcement and harm reduction activities has been effected elsewhere with positive results.35–39 Any large-scale police operation has the potential to unsettle drug users and disrupt their uptake of services. However, negative effects could be reduced by better cooperation and coordination of efforts among public health, substance abuse, and police agencies.40 For example, the launching of the Philadelphia operation could have been linked to an intensive outreach effort to enroll IDUs in drug treatment, and the police could have been instructed to avoid interference with syringe exchange program users or to refer IDUs to the syringe exchange program. Integrating policing and health planning also highlights important choices about the use of scarce government resources: the annual cost of the policing operation is 57 times the syringe exchange programs’ yearly city funding allocation (C. Cook, MSS, MLSP, written communication, January 23, 2003).41

Acknowledgments

Work on this project was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant UO1AI48014-04). Burris’s work was supported in part by the Substance Abuse Policy Research Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Note. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation or the Substance Abuse Policy Research Program.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors C. Davis designed the study, conducted research and wrote the original brief. S. Burris originated the concept for the study, originated and conceptualized ideas and contributed substantially to the brief. J. Becher conducted statistical analyses and contributed to the brief. K. Lynch conducted statistical analyses. D. Metzger oversaw the study, helped to conceptualize ideas, and reviewed drafts of the brief.

References

- 1.AIDS Activities Coordinating Office Epidemiology Unit. AIDS Surveillance Quarterly Update. Philadelphia, Pa: City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health; December 31, 2001.

- 2.HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2001. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. Report 13(2).

- 3.Gibson DR, Flynn NM, Perales D. Effectiveness of syringe exchange programs in reducing HIV risk behavior and HIV seroconversion among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2001;15:1329–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drucker E, Lurie P, Wodak A, Alcabes P. Measuring harm reduction: the effects of needle and syringe exchange programs and methadone maintenance on the ecology of HIV. AIDS. 1998;12(suppl A):S217–S230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ksobiech K. A meta-analysis of needle sharing, lending, and borrowing behaviors of needle exchange program attenders. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15: 257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Des Jarlais D, Grund J, Zadoretzky C, et al. HIV risk behaviour among participants of syringe exchange programmes in central/eastern Europe and Russia. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Executive Order No. 04-92 of the Hon. Edward G. Rendell, Mayor of Philadelphia. July 27, 1992.

- 8.Street J. Mayor’s Report on City Services. Philadelphia, Pa: Mayor’s Office; 2002.

- 9.Bluthenthal R. Drug paraphernalia and injection-related infectious disease risk among drug injectors. J Drug Issues. 1999;29:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhodes T, Mikhailova L, Sarang A, et al. Situational factors influencing drug injecting, risk reduction and syringe exchange in Togliatti City, Russian Federation: a qualitative study of micro risk environment. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:39–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross T. Using and dealing on Calle 19: a high risk community in central Bogota. Int J Drug Policy. 2002; 13:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rich JD, Strong L, Towe CW, McKenzie M. Obstacles to needle exchange participation in Rhode Island. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:396–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aitken C, Moore D, Higgs P, Kelsall J, Kerger M. The impact of a police crackdown on a street drug scene: evidence from the street. Int J Drug Policy. 2002; 13:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maher L, Dixon D. Policing and public health: law enforcement and harm minimisation in a street-level drug market. Br J Criminol. 1999;39:488–511. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koester S. Copping, running and paraphernalia laws: contextual and needle risk behavior among injection drug users in Denver. Hum Organ. 1994;53: 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bluthenthal R, Kral A, Erringer E, Kahn J. Collateral damage in the war on drugs: HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 1999;10: 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grund JP, Heckathorn DD, Broadhead RS, Anthony DL. In eastern Connecticut, IDUs purchase syringes from pharmacies but don’t carry syringes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10: 104–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burris S, Kawachi I, Sarat A. Integrating law and social epidemiology. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30: 510–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1996.

- 20.Gorenstein N. Police costs soar with antidrug plan. Philadelphia Inquirer. July 20, 2002;sect A:01.

- 21.Flander S. As Philadelphia’s streets get safer, drug dealers take up delivery. Centre Daily Times. November 22, 2002. Available at: http://www.centredaily.com. Accessed October 22, 2003.

- 22.Gale D. Safe street? Philadelphia City Paper. May 1, 2003. Available at: http://citypaper.net/articles/2003-05-01/hallmon.shtml. Accessed October 28, 2003.

- 23.Broadhead RS, van Hulst Y, Heckathorn DD. The impact of a needle exchange’s closure. Public Health Rep. 1999;114:439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burris S, Blankenship K, Donoghoe M, et al. Addressing the “risk environment” for injection drug users: the mysterious case of the missing cop. Milbank Q. 2004;82:125–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrison P, Beck A. Prisoners in 2002. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; July 2002.

- 26.Hagan J, Peterson R. Criminal Inequality in America: Patterns and Consequences. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press; 1995.

- 27.Snyder HN. Juvenile Arrests 1998. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1999.

- 28.Fagan J, Davies G. Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urban Law J. 2000;28:457–504. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tonry M. Malign Neglect: Race, Crime and Punishment in America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995.

- 30.Marx MA, Crape B, Brookmeyer RS, et al. Trends in crime and the introduction of a needle exchange program. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1933–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Final Report of the Evaluation of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injection Centre. Sydney, Australia: MSIC Evaluation Committee; 2003.

- 32.Watters JK, Estilo MJ, Clark GL, Lorvick J. Syringe and needle exchange as HIV/AIDS prevention for injection drug users. JAMA. 1994;271:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guydish J, Bucardo J, Young M, Woods W, Grinstead O, Clark W. Evaluating needle exchange: are there negative effects? AIDS. 1993;7:871–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institutes of Health. Interventions to prevent HIV risk behaviors. NIH Consens Statement. 1997; 15(2):1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Midford R, Acres J, Lenton S, Loxley W, Boots K. Cops, drugs and the community: establishing consultative harm reduction structures in two Western Australian locations. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacob J, Stover H. The transfer of harm-reduction strategies into prisons: needle exchange programmes in two German prisons. Int J Drug Policy. 2000;11: 325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh M. A harm reduction programme for injecting drug users in Nepal. AIDS STD Health Promot Exch. 1997(2):3–6. [PubMed]

- 38.Juniartha IW. Bali police chief supports methadone program. Jakarta Post. July 24, 2003. Available at: http://www.thejakartapost.com/detailnational.asp?fileid=20030724.D03&irec=6. Accessed July 26, 2003.

- 39.Engelsman EL. Dutch policy on the management of drug-related problems. Br J Addict. 1989;84: 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lough G. Law enforcement and harm reduction: mutually exclusive or mutually compatible? Int J Drug Policy. 1998;9:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Twyman A. $58 Million sought to cover police costs of Safe Streets plan. Philadelphia Inquirer. December 5, 2002:B-03.