Abstract

The community action model is a 5-step, community-driven model designed to build communities’ capacity to address health disparities through mobilization. Fundamental to the model is a critical analysis identifying the underlying social, economic, and environmental forces that create health and social inequities in a community. The goal is to provide communities with the framework necessary to acquire the skills and resources to plan, implement, and evaluate health-related actions and policies.

The model was developed in the context of tobacco-related health disparities. Concrete policy outcomes demonstrate the model’s potential application to a wide variety of grassroots policy development efforts.

Researchers have documented that socioeconomic status is an indicator of health status, and there is mounting evidence that the gap between rich and poor contributes to health disparities.1–3 Because race and ethnicity are major determinants of socioeconomic status, residents of communities of color are more likely to be in poor health and to die early owing to disparities in health. Tobacco-related illness is no exception: cigarette smoking is a major cause of disease and death among African American, Asian American/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Hispanic/Latino communities, with lung cancer being the leading cause of death in each case.4

Asthma, one of the most widespread chronic conditions in the United States, is especially prevalent in low-income communities in which there are high rates of tobacco use.5 The synergistic effects of tobacco smoke and mold can cause or exacerbate asthma, particularly among children.6 In addition, minority children are more likely to be exposed to hazards such as environmental tobacco smoke, mold, pests, and lead because of the dilapidated conditions often found in low-income housing.7 Exposure to these agents may play a part in the higher and disproportionate rates of asthma-related diseases seen among African Americans and Latinos.5

A key feature of the state of California’s tobacco control program has been to “to expose the tobacco industry as a very powerful, deceptive, and dangerous enemy of the public’s health.”8(p8) In fact, the tobacco industry has exposed itself through the cache of documents released to the public as a result of recent litigation, documents that illustrate a long history of deceit, deception, and duplicity in the way the industry does business.9 Through manipulative and targeted advertising, disinformation campaigns refuting the health consequences of smoking, and political lobbying, the tobacco industry has grown and prospered over the years,10 and, as the industry has prospered, the number of people who die as a result of tobacco-related diseases has increased.

It is vital that any analysis of health disparities in tobacco-related illnesses be conducted in the context of the global economic structures that promote these disparities. Health disparities in tobacco-related illnesses can be addressed by integrating an analysis of the tobacco industry with an assessment of inequities in housing; corporate food production; and elements of the global economy such as privatization (transforming public entities such as health care providers into private, for-profit entities), deregulation (eliminating laws and regulations that, in many cases, protect health and the environment), and free trade (free movement of products and services across borders).

Transnational tobacco companies use the tools of the global economy to engage in aggressive marketing and promotion targeted at communities of color, women, young people, the lesbian/gay/transgender community, and communities of low socioeconomic status.11 The result is higher tobacco use prevalence rates in these communities and subsequent disproportionate rates of tobacco-related diseases.

There are strong similarities between the promotional and marketing activities engaged in by the tobacco industry and those employed by food corporations to advertise unhealthy foods, especially to children.12 Kraft and Nabisco, subsidiaries of Philip Morris/Altria, combined to represent the second largest corporate food producer in the world.13 These food corporations, like their parent tobacco company, aggressively promote their products and benefit from market-based trade agreements. The success of their marketing strategies can contribute to both greater food insecurity (a community’s inability to access nutritious, affordable, and culturally appropriate food) and childhood obesity as people consume more commercial, packaged food products and less fresh, homemade food. Such companies are increasingly under attack for contributing to the epidemic of childhood obesity in the United States, so much so that Kraft announced in July 2003 that it would discontinue advertising aimed toward children and develop more nutritious products.14

Obesity appears to disproportionately affect communities of color.15 In some low-income neighborhoods, advocates have found that the 3 most accessible products in stores are alcohol, cigarettes, and junk food.16 Local tobacco control projects are combining efforts to combat tobacco promotion with grassroots organizing efforts designed to counter the food insecurity that has resulted from the large market penetration of tobacco company food subsidiary products in these low-income neighborhoods.

THE COMMUNITY ACTION MODEL

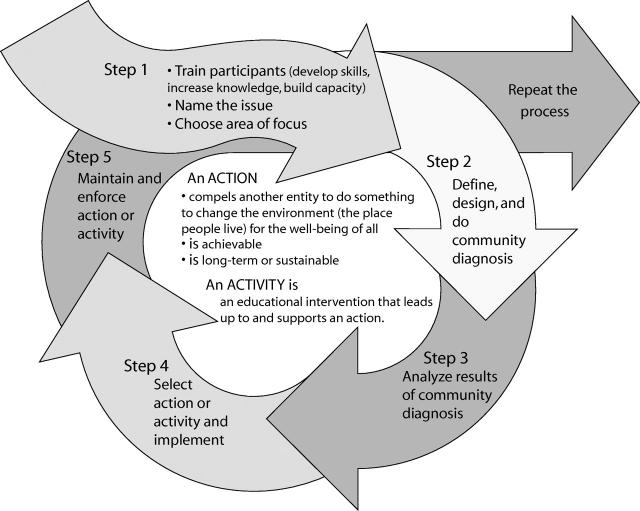

The community action model is a 5-step process (Figure 1 ▶) designed to address the social determinants of tobacco-related health disparities through grassroots policy development. In California, the San Francisco Tobacco Free Project (SFTFP) is part of the Community Health Promotion and Prevention section of the San Francisco Department of Public Health and is responsible for developing and implementing a comprehensive tobacco control plan for San Francisco. The SFTFP has implemented the model since 1996 through funding community-based organizations (CBOs) in San Francisco that, in turn, work with community advocates (community members). The community action model has been successfully implemented with community members to address social determinants of tobacco-related health disparities. The 5 steps of the model have been applied to address social determinants of other health disparities as well and are designed to move toward environmental change in the form of a policy or change in organizational practices.

FIGURE 1—

The 5 steps of the community action model process.

The community action model is based on the theory of Paulo Freire, a Brazilian educationalist who integrated educational practice with liberation from oppressive conditions. Freire’s work emphasized dialogue, praxis, the grounding of education in lived experiences, and heightening people’s consciousness to enhance the belief that they have the power to transform reality, specifically with respect to addressing oppression.17 The community action model involves participatory action research approaches and is asset based (i.e., it builds on the strengths of a community to create change from within). Its intent is to create change by building community capacity, working in collaboration with communities, and providing a framework for residents to acquire the skills and resources necessary to assess the health conditions of their community and then plan, implement, and evaluate actions designed to improve those conditions.

The goals of the model are twofold. The first goal is promoting environmental change by moving away from projects that focus solely on changing individual lifestyles and behaviors to mobilizing community members and agencies to eliminate characteristics of the community that promote economic and environmental inequalities. The second goal is to assist people in acquiring the skills needed to do it themselves: as mentioned, the community action model provides a framework for community members to acquire the skills and resources they need to assess and improve the community’s health.

Inequities in social systems—whether one speaks of politics, health care, economics, or justice—contribute to health disparities. However, public health solutions frequently focus on persuading people to change their “unhealthy” behaviors or to make “healthier” lifestyle decisions. Unfortunately, this approach places the onus on the individual and does not challenge the social structures that shape many of our choices and decisions.18 People cannot improve their health through individual behavior change alone; rather, any solution must focus on environmental change.18 The community action model is designed to increase the capacity of communities and organizations to address the social determinants of health at the environmental change level.

INTERVENTION COMPONENTS

The community action model involves a 5-step process (described in the sections to follow and illustrated in Figure 1 ▶): (1) skill-based training, in which community advocates select an area of focus; (2) action research, in which advocates define, design, and conduct a community diagnosis; (3) analysis, in which advocates assess the results of the community diagnosis and prepare findings; (4) policy development, in which advocates select, plan, and implement an environmental change action and educational activities intended to support it; and (5) implementation, in which advocates seek to ensure that the policy outcome is enforced and maintained. The SFTFP has developed a curriculum in English, Spanish, and Chinese and the curriculum includes specific activities designed to assist advocates in implementing the aforementioned steps.19

The community action model is designed to have a lasting impact by developing the capacity of both individuals and organizations to address disparities in health by creating environmental change through policy enactment. The Tobacco-Free College Campus Project is one example of the successful implementation of the model. The goal of this project was to educate the San Francisco State University (SFSU) campus community about the tobacco industry and its harmful practices and to mobilize the community to support tobacco-free policies on the campus, and it successfully advocated adoption of administrative policies to permanently end financial ties between the college and tobacco corporations.

Step 1

Step 1 of the community action model involves organizing a group of 5 to 15 community members, either youth or adults, to serve as advocates. As part of this step, health educators provide these advocates with skill-based training in their particular project area. This initial training allows advocates to have a clear and concrete understanding of the community action process, along with specific activities included in the community action model curriculum, helping them identify and focus on a specific area of work. Also during step 1, advocates engage in dialogue about concerns and issues they want to address and choose a focus area that has meaning to their community.

A key component of step 1 is “naming the issue,” whereby advocates use “codes” to critically analyze and identify the underlying social, economic, and environmental forces creating the health and social inequalities that need to be addressed. This is a crucial step in that no solution to dismantle inequalities can be reached without the full involvement and leadership of the communities most affected.

For example, a core group of SFSU student advocates were recruited and trained to carry out and lead the tobacco-free education and policy advocacy campaign. To ensure that these student advocates were prepared to meet the demands of the project, they completed extensive training during the project’s first year, learning about tobacco control issues and policies. They were given articles to read and research assignments to complete. Areas covered included tobacco advertising; tobacco stock divestment; tobacco economics and profits; marketing aimed at people of color, youth, and residents of foreign countries; environmental tobacco smoke; tobacco litigation; subsidiary products; tobacco and campaign finance; tobacco and individual health; tobacco and international trade/global economy; tobacco and agriculture/pesticides; and tobacco smuggling.

Step 2

Step 2 of the community action model involves advocates in defining, designing, and implementing a community diagnosis (“action research”) to determine the root causes of a community issue and outline the resources necessary to overcome it. This step is key in that health educators and program evaluators work closely with advocates to design and implement tools that can be used to assess the extent of the health issue or issues affecting the community. Advocates outline the types of research they will conduct and then design the tools needed. For example, they may interview key leaders, conduct surveys, and research existing records. The community action model curriculum provides worksheets and examples of how to carry out this step in the “designing your diagnosis plan” activity.

The first task for the SFSU advocates was to conduct a diagnosis of the tobacco environment in regard to their campus community. They used key informant interviews and surveys to collect information from each campus as part of the community diagnosis. Each advocate group documented the following data: (1) current tobacco-related campus policies, (2) types of decisionmaking bodies and processes, (3) extent of tobacco availability, (4) extent of tobacco sponsorship at college events, and (5) amount of tobacco stock in the university’s investment portfolios.

Step 3

Step 3 involves analyzing the results of the diagnosis and preparing findings. At this point, advocates learn how to input and analyze data and acquire the skills they need to present their findings in simple yet visually compelling formats. This step encourages advocates’ “ownership” of the results they have discovered in regard to their focus area. During this step, advocates also learn how to use the statistics they have uncovered in making presentations to student groups (e.g., La Raza Student Association, Black Student Union), policymakers, and the media.

SFSU student advocates learned, through a verbal statement from the Chief Executive Officer of the SFSU Foundation, that the foundation had no money invested in tobacco and then received a letter from the foundation’s investment manager, Mellon Private Asset Management, confirming that statement. However, the students discovered that the SFSU Foundation had no written policy prohibiting investment in tobacco stocks.

Step 4

Step 4 involves advocates in selecting, planning, and implementing an “action” or “activity” to address their issue of concern. Here advocates use the findings of their analysis to determine solutions to the issues they have chosen to address. The “action” defined represents the desired policy outcome for the project, and it should meet 3 criteria: (1) it should be achievable, (2) it should have the potential for sustainability, and (3) it should compel members of groups, agencies, or organizations to change their community for the well-being of all.

“Activities,” on the other hand, are defined as the educational and organizational interventions that lead up to and support the outcome. If a project has a short time line and no resources, advocates might identify an action (to accomplish with future funding and resources) and then dedicate existing time and resources to activities related to that action. In this step, advocates develop and implement an action plan that may be in the form of outreach, media advocacy, development of a model policy, or advocating for a policy. The community action model curriculum includes an “actions for health” activity that helps groups delineate the difference between a short-term solution based on individual behaviors and a longer, more sustainable environmental change outcome.

SFSU student advocates created a grass-roots coalition of students, student organizations, faculty departments, and community advocacy groups to work for policies that would end financial ties between SFSU and the tobacco industry. They labeled this coalition “Together Against Campus Tobacco Investment Campaign,” or TACTIC. TACTIC went on to successfully advocate for the SFSU Foundation board of directors to pass (unanimously) a written policy permanently prohibiting investment in tobacco companies.

Step 5

Step 5 focuses on enforcing and maintaining the action identified to ensure that the advocates’ efforts will be maintained over the long term and enforced by the appropriate bodies. As with the other steps, the community action model provides information on how to conduct enforcement activities (e.g., polls and compliance surveys). For example, after the SFSU Foundation board of directors unanimously approved the policy to permanently prohibit investment in tobacco companies, the student advocates worked toward persuading the foundation to adopt a transparency policy that would make public its investments as a way to ensure that the policy was enforced.

EVALUATION OF THE COMMUNITY ACTION MODEL

The success of an action, as defined by the community action model, hinges on policy development, which involves a political process beyond the control of advocates. Thus, rather than simply assessing whether or not an action was successfully completed, the community action model evaluation methodology assesses both the implementation of the project and its results. As a consequence, one of the goals of the evaluation is to determine whether the community action model process was followed and whether an action was identified that met the defined criteria.

The evaluation examines 4 questions: (1) Was the community action process completed? (2) Did the action selected meet the defined criteria? (3) Did the advocates’ capacity increase? and (4) Did the capacity of the involved agency or agencies increase? These questions are measured through a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods such as observation, written reports (project leaders are required to submit a rationale for choosing their action), interviews, and pre- and postintervention surveys. The model has been successful in increasing the capacity of both advocates and CBO staff and in successfully completing a number of health-related actions. In addition, brief case studies have been formulated for various tobacco-related community action model projects to document the processes involved and lessons learned.

Between 1995 and 2004, 37 projects were funded in 6 funding cycles. Thirty of these projects implemented a plan focusing on the accomplishment of an action meeting the 3 criteria described earlier, and 28 successfully accomplished the action itself. Successful outcomes of community action model projects are listed in Table 1 ▶. Future evaluation methodologies are being planned to address long-term sustainability and to allow comparisons of elements leading to success and capacity in agencies and elsewhere.

TABLE 1—

Past Actions Successfully Accomplished With the Community Action Model

|

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

As described, the community action model is based on capacity building and community organizing strategies and is designed to make issues relevant to the community. There are a number of challenges facing the implementation of a model rooted in community organizing. First, although the paradigm of public health is shifting, the primary focus remains on people changing their “unhealthy” behaviors or making “healthier” lifestyle decisions. As a result, many CBOs have traditionally received grants from funding sources that focus on behavior change models. These CBOs tend to lack the infrastructure necessary to coordinate a community-driven advocacy campaign based on action research and focusing on policy development. Second, lack of resources is a continual challenge, in that change at the environmental level requires sustained funding over time and is labor intensive, thereby limiting the number of projects that can be funded.

Finally, categorical funding often requires the community action model to have a predetermined area of focus that, depending on the situation, may make it more difficult to ensure that an issue is relevant to the community in question. For example, the SFTFP receives funding from Proposition 99, the California State tobacco tax, and the master settlement agreement reached between the tobacco companies and the state attorneys general. This funding structure requires that tobacco control be the focus of the community action model projects that receive funding, but tobacco control may or may not be of greatest concern to a particular community.

CHANGES IN IMPLEMENTATION

Although the philosophy behind the community action model has not changed, there have been changes in the implementation of the model itself to address some of the factors that present challenges to the work involved. These changes have included clearly defining the action criteria, amending the funding and application process, altering the way in which the model is operationalized, and supplementing the training and consultation component.

Defining an Action

In early projects, actions included conducting health fairs, making presentations, and coordinating awareness-raising events; thus, a number of these projects focused on individual behavior change. This led to the need to alter the definition of an action so that it would meet the 3 criteria described earlier—achievability; potential for sustainability; and potential to persuade groups, agencies, or organizations to make policy changes—in terms of focusing on environmental change.

Streamlining the Funding and Application Process

Alterations in the community action model funding process were made in an attempt to fund organizations more focused on assisting communities in effecting environmental change. SFTFP staff identified 3 criteria that would maximize an organization’s ability to successfully implement the community action model. First, the organization must be community based; second, it must demonstrate a history of or interest in activism; and, third, it must have the infrastructure to support the staff necessary to implement a project focused on system change. These criteria were integrated into the application and evaluation standards used to score applicants. The application specifically indicated that the funded CBO would be required to implement the community action model, select an action meeting the model’s criteria, and implement a community plan to work toward successful completion of the action. The request for funding application included a list of potential actions that met the model’s criteria as a way to illustrate the types of projects that funded CBOs might work on.

In addition, many CBOs that were not directly service based were identified and included in the outreach mailing lists. Because activist-oriented CBOs tend to be relatively small, often making it difficult for them to meet the requirements of a city government contract, the SFTFP funded a sponsor organization with the infrastructure necessary to meet such requirements. This enabled smaller CBOs to subcontract on larger contracts. Also, this structure allowed SFTFP staff to streamline the application process. The original application was lengthy and bureaucratic, while more recent applications have been reduced to 4 to 6 pages.

Operationalizing the Community Action Model

As just mentioned, activist CBOs tend to be small and to have little infrastructure with which to administer city contracts. In response, SFTFP staff developed simple work plans, budgets, and budget revision and invoice processes to alleviate some of the administrative burden of implementing the model. There were other requirements as well, including a budget for the project coordinator, stipends for community advocates, and budgets covering incentives for program participants. For example, projects could use their budgets to purchase computers and pay for Internet access.

Supplementing the Training and Technical Assistance Component

Changes in technical assistance and training were made to address the challenge of working with groups that may be oriented toward individual behavior change and to develop strategies to ensure that the issue or issues addressed are relevant to the community in question. For example, the 5 steps of the community action process were reinforced in an interactive curriculum and integrated in each funded CBO’s work plan. SFTFP staff developed and provided training sessions that walked project staff and supervisors through the 5-step process. These sessions are continually adapted and streamlined, and the original 5-day training session has been reduced to a 3-hour orientation session supplemented with skill-specific training on an as-needed basis.

In addition, all funded project staff attend regular meetings to collectively brainstorm and collaborate, and regular meetings are held between specific funded project staff and SFTFP staff. This process greatly enhances ongoing collaboration and the potential for project success. Separate training aimed at agencies funded to implement the community action model is also provided; these sessions address, along with other elements, how to set up the necessary infrastructure, provide administrative support (e.g., budgets, work plans, staffing), and determine compensation for advocates (e.g., stipends or incentives).

SFTFP project liaison staff meet regularly with agency staff to solve problems, brainstorm, and share resources. In addition, training materials integrate an analysis of the root causes of and solutions to the health issue addressed, including, in the case of tobacco, the role of the transnational tobacco companies and the elements of the corporate-led global economy. Funded community action model projects partner with CBOs in countries with fewer resources, participate in “exchange” meetings, and collaborate on joint environmental change actions.

Media advocacy is a powerful strategy in any community organizing effort. However, many small CBOs do not have the necessary resources or technical expertise to implement successful media advocacy campaigns. In response, SFTFP hired a public relations and advertising firm to provide technical assistance and consultation to the funded projects. Although SFTFP continues to support media advocacy efforts, SFTFP staff realized that a “one-size-fits-all” media contractor was impossible to find. In lieu of a single contract, SFTFP now provides media funds to each project and allows project staff to identify a culturally competent media consultant.

The diagnosis or action research component is another central facet of the community action model. To build the capacity of CBOs to design appropriate diagnosis plans, SFTFP funds an evaluation contractor to provide technical assistance and consultation to these organizations. SFTFP staff and evaluators may not have in-depth knowledge of a particular community’s issues and concerns; thus, ongoing collaboration is essential and must involve mutual information sharing and respect for the community-driven aspect of the process. During the diagnosis phase (step 2), the evaluator works closely with advocates as they define, design, and implement the research.

CONCLUSIONS

Collaboration is central to the implementation of the community action model, given that solutions to health disparities must be identified in partnership with the community. As described earlier, the SFTFP provides technical assistance and training to the staff members and advocates who are implementing the model. As a result, there is continual tension between the community-driven elements of the model and the technical assistance and support provided to facilitate the ability of both staff and advocates to acquire the skills to build their capacity to pursue environmental change policies.

CBO staff and advocates make the links between a variety of issues of concern to them. The SFTFP staff liaisons, evaluation contractor, and media consultants provide ongoing technical assistance and training. This approach allows for collaboration and linkages between the funding focus—tobacco control—and other issues of concern to particular communities such as immigrant rights, housing issues, environmental justice, and food security. For example, 1 project focusing on food security issues in a low-income community of color in San Francisco is advocating for a “good neighbor” corner store policy that would promote inner-city residents’ access to healthy alternatives to tobacco subsidiary food products.

The SFTFP implements a variety of strategies and activities that lead to successful completion of the 5 steps of the community action model. As part of the requirements associated with funding, CBOs must complete the entire 5-step process, including selection of an action and completion of a plan to achieve it. The design of the model, along with intensive technical assistance, training, and consultation on the part of SFTFP staff, the evaluation contractor, and media contractors, is intended to facilitate this process. These funding requirements are included in the memorandum of understanding, work plan, deliverables, and so forth. Also, because the community action model is designed to be community driven and community owned, the completed project has more meaning to community members.

The community action model is intended to have a lasting impact in developing both individuals’ and organizations’ capacity to continue social justice work by creating environmental policy change. Because health disparities are rooted in social inequities, empowering the most affected members of the community to acquire the skills needed to change social structures and inequities through environmental change will assist in addressing such disparities. Although the model has focused, by necessity, on tobacco-related issues, the skills and capacities developed are transferable to other issues that affect communities and prevent their residents from being healthy.

In the case of tobacco control in California, the shift from focusing on smoking cessation programs to focusing on norm change is complete. Health educators involved in the implementation of the community action model are currently addressing a number of other challenges that will help to advance learning and action related to social determinants of health. Projects sponsored by the San Francisco Department of Public Health that address violence prevention, infant mortality, pedestrian safety, and substance abuse are integrating the model into their work plans. To further facilitate the transferability of the community action model to these health issues, a “facilitator guide” has been developed.

In addition, the curriculum continues to be revised to be increasingly “user friendly.” Health educators and advocates meet regularly to determine how to best implement each step of the process, develop appropriate activities to use with advocates, and establish lists of potential actions in each issue area. The community action model continues to evolve toward a more manageable and simplified program model such that some of the instructors at a local San Francisco community college now use it in semester-long classes in which students work in teams and implement the 5 steps in short time periods with no resources.

Acknowledgments

The San Francisco Tobacco Free Project is sponsored through funds from California Proposition 99 and the tobacco master settlement agreement.

This article was based on a paper presented at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Forum “Social Determinants of Health Disparities: Learning From Doing,” held in Atlanta, Ga, October 2003.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors All of the authors contributed equally to writing the article.

References

- 1.Anderson RT, Sorlie P, Backlund E, et al. Mortality effects of community socioeconomic status. Epidemiology. 1997;8:42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haan M, Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Poverty and health: prospective evidence from the Alameda County study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125:989–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49:15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among US Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1998.

- 5.Asthma: A Concern for Minority Populations. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health; 2001.

- 6.Etzel R. How environmental exposures influence the development and exacerbation of asthma. Pediatrics. 2003;112:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aligne C, Auinger P, Byrd R, et al. Risk factors for pediatric asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000; 162:873–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Model for Change: The California Experience. Sacramento, Calif: California Department of Health Services; 1998.

- 9.Trust Us, We’re the Tobacco Industry. Washington, DC: Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids; 2001.

- 10.Hammond R. Addicted to Profit: Big Tobacco’s Expanding Global Reach. Washington, DC: Essential Action; 1998.

- 11.Chopra M, Darnton-Hill I. Tobacco and obesity epidemics: not so different after all? BMJ. 2004;328:558–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Story M, French S. Food advertising and marketing directed at children and adolescents in the US. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2004;1:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts WA Jr. The “big” gets bigger: Kraft Foods Inc. has a successful year. Prepared Foods. September 2001:12, 37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins M. Kraft to go lean, starve appetite for obesity suits. Washington Times. July 2, 2003:A1.

- 15.Koplan J, Liverman C, Kraak V, eds. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2004.

- 16.Carpio C. LEJ/Youth Envision Good Neighbor Project: Diagnosis Findings. San Francisco, Calif: BayView Hunter’s Point; 2003.

- 17.Smith MK. Paulo Freire. Available at: http://www.infed.org/thinkers/et-freir.htm. Accessed January 11, 2005.

- 18.Caira NM, Lachenmayr S, Sheinfeld J, et al. The health educator’s role in advocacy and policy: principles, processes, programs, and partnerships. Health Promot Pract. 2003;4:303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.San Francisco Tobacco Free Project. Available at: http://sftfc.globalink.org. Accessed February 8, 2005.