Abstract

The National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal (NSNR) is a central component of British policy to reduce health disparities. This program seeks to improve local socioeconomic and physical environments through the intensive regeneration of disadvantaged communities. We describe the challenges facing evaluators tasked with assessing the impacts of 1 component of the NSNR—the New Deal for Communities initiative—and explore techniques that may be adopted in the evaluation process.

The commitment to reduce health inequalities has been a key feature of British policy development since 1997, and action has not been limited to the National Health Service, the UK system of national medical services. A string of policy documents recognizing the role of the wider socioeconomic environments in determining health1–5 have identified 4 areas where action may have the greatest impact: supporting families, mothers, and children; engaging communities and individuals in addressing health inequalities; preventing illness and providing effective treatment; and addressing the underlying determinants of health.

The National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal (NSNR) is 1 of the major policy programs.6,7 Integral to the NSNR is the concept of addressing issues of deprivation and social inequalities by developing healthy communities and neighborhoods. Specifically, community members are encouraged to work with professional, statutory, and volunteer organizations to develop a program that works toward reducing crime and unemployment as well as improving education, housing, and community health and well-being.

A key element of the NSNR is the New Deal for Communities (NDC) initiative, an area-based regeneration initiative targeted at 39 of the most deprived communities in England.8 The NDC initiative supports the intensive regeneration of neighborhoods through the creation of NDC partnerships between local residents, community and volunteer organizations, local authorities, businesses, and government agencies. Each community is eligible to receive approximately £50 million (US $90 million) between 1999 and 2008 to develop program activities that address the NSNR’s key issues, including those related to health and health disparities.

The NDC initiative offers a unique opportunity for research into how health improvement and the reduction of health inequalities may be brought about by reinvigorating local economies, helping people compete for jobs, tackling antisocial behavior and crime, and reorienting existing service delivery programs. At a national level, both the Neighbourhood Renewal Unit and the Department of Health have commissioned substantial evaluations of the NDC initiative; the former evaluation focused on all aspects of program performance and the latter primarily on an analysis of the social determinants of patterns and trends in health disparities.9 This brief presents basic components and challenges of an assessment of how the NDC initiative may impact health within the West Midlands region of England.

METHODS

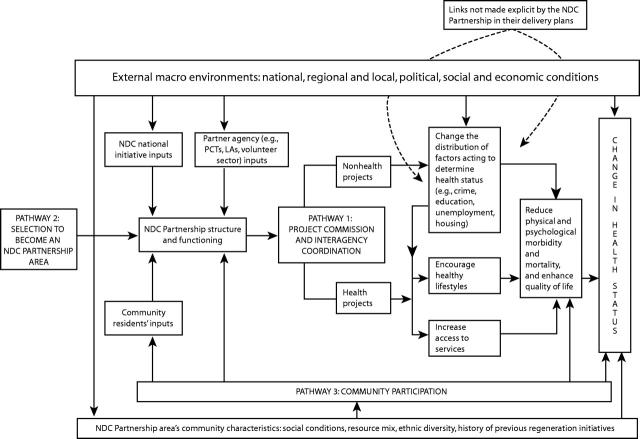

We developed a model to identify key processes in the analysis of how the NDC initiative may impact health.10 Figure 1 ▶ illustrates the ways in which these processes represent an embryonic “theory of change” for achieving health gains in NDC communities.

FIGURE 1—

Pathways through which the New Deal for Communities affects health and facilitates change in health status (adapted from Parry et al.10).

Note. NDC = New Deal for Communities; PCT = primary care trust; LA = local authority. Dotted lines indicate the unrealized potential of projects’ non-health capacity to affect health.

RESULTS

Figure 1 ▶ illustrates the 3 key processes, or pathways of change, we identified. First, the commissioning of projects within the “health” and “nonhealth” domains has the potential to bring about health improvements to targeted populations—the former through modifications to health care service delivery or via health-promoting activities, for example, and the latter by changing the distribution of social determinants of health (pathway 1). Second, the process of identifying, defining, and selecting neighborhoods eligible to participate in the NDC initiative has the potential to impact the health and well-being of residents, both negatively via stigmatization and positively through recognition and thus legitimization of need (pathway 2). Finally, the bottom-up and participatory nature of the NDC initiative may be considered an intervention in its own right through its potential to build or strengthen social networks and organizational capacity among participating groups (pathway 3). Because NDC neighborhoods are not isolated from the wider macro socioeconomic environment, significant external changes in the wider context within which these communities operate must also be factored into the equation.

DISCUSSION

In classical epidemiological theory, the ability to predict the impacts of any intervention is critically dependent upon a synthesis of all available existing evidence to produce a likely effect estimate, followed by the application of this estimate to the affected population. The evaluation of the impact of a multifaceted policy program such as the NDC initiative is obviously more complicated.

Here, the interventions comprise a variety of interrelated programs and projects enacted within a dynamic, open population. In addition, the delivery of programs with similar objectives—for example, efforts to improve educational attainment among youngsters from deprived backgrounds—may vary substantially between NDC sites. Thus, alternative theory-driven evaluation strategies are required. Theoretically, the potential impact of each program and project commissioned by an NDC Partnership can be assessed by reference to the existing evidence; for example, what do previous studies tell us about the impact of before-school programs such as “breakfast clubs” on children’s engagement in learning activities during the day? Here, evidence tends to refer primarily to the experimental literature, and there are substantial drives11–13 to develop such evidence databases.

Evidence may also include relevant knowledge and experiences of local people and others involved in the NDC initiative.14 Such evidence can be made explicit and incorporated into the analytical framework through approaches such as the theories-of-change framework.15,16 This requires participants involved in a change process to articulate theories of how and why they think the actions they are taking will lead to the outcomes they aim to achieve. The articulation of such theories identifies the assumed pathways of change. This articulation, in turn, starts to define the type of data to be collected in order to establish whether those pathways are being followed and whether expected short- and medium-term outcomes are observed.

We do not want to suggest that there are not very real difficulties in conceptualizing and measuring outcomes of different kinds. The key point we wish to emphasize is the importance of grounding the assessment of the health impacts of complex community initiatives such as the NDC initiative in theory-based evaluation that takes into account the context within which the program is operationalized. Moreover, such theorizing may also increase the likelihood of identifying potential unintended effects of the NDC initiative that might impact adversely on residents’ health—for example, local renewal activities could push out low-income families as rents are increased. However, even strong advocates of theory-based evaluation recognize that, on their own, such approaches have limited capacity to predict all that could happen absent the intervention.

Consequently, some researchers are seeking to integrate theory-based program evaluation into more traditional quasi-experimental study designs with the use of control groups.17 The adoption of such a study design may, in part, assist with factoring in external changes in the wider context within which NDC communities operate. In the West Midlands, we are using a mixed-method approach to evaluate the health impacts of the NDC initiative by adopting a quasi-experimental design whereby trends in health indicators (e.g., accident rates, hospital admission statistics) measured in the NDC areas and a series of control populations will be compared over time. Additionally, qualitative data gathered from informal discussions with NDC staff, focus groups with local residents, photographic records, interviews with health care professionals working in the NDC areas, and analyses of local, regional, and national print media are used to understand why germane changes and trends may be emerging.

This work is still at an early stage, but we hope it will shed further light on how urban regeneration might improve health and reduce health inequalities. Findings from this work will be reported in future publications as they become available.

Acknowledgments

The evaluation of the health impacts of the New Deal for Communities initiative in the West Midlands is funded by the NHS Executive (West Midlands) of the Department of Health.

Human Participant Protection The protocol for the health impacts evaluation described in this brief was approved by the West Midlands multicentre research ethics committee (Reference MT/NM/MREC/02/7/65).

Peer Reviewed

Contributors J. Parry is principal investigator on this project. Both authors jointly originated and wrote the brief.

References

- 1.Department of Health. Tackling Health Inequalities: A Programme for Action. London, England: Department of Health Publications; 2003.

- 2.Acheson D. Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health: Report. London, England: The Stationary Office; 1998.

- 3.Department of Health. Tackling Health Inequalities: Consultation on a Plan for Delivery. London, England: Department of Health Publications; 2001.

- 4.Department of Health. Tackling Health Inequalities: The Results of the Consultation Exercise. London, England: Department of Health Publications; 2002.

- 5.Department of Health. Tackling Health Inequalities: Summary of the 2002 Cross-Cutting Review. London, England: Department of Health; 2002.

- 6.Social Exclusion Unit. Bringing Britain Together: A National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal. London, England: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Social Exclusion Unit; 1998.

- 7.Social Exclusion Unit. A New Commitment to Neighbourhood Renewal: National Strategy Action Plan. London, England: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Social Exclusion Unit; 2001.

- 8.Neighbourhood Renewal Office. Our Programmes: New Deal for Communities. Available at: http://www.neighbourhood.gov.uk/ndcomms.asp. Accessed December 18, 2004.

- 9.NDC National Evaluation. NDC National Evaluation Web site. Available at: http://ndcevaluation.adc.shu.ac.uk/ndcevaluation/Home.asp. Accessed December 18, 2004.

- 10.Parry J, Laburn-Peart K, Orford J, Dalton S. Mechanisms by which area-based regeneration programmes might impact on community health: a case study of the New Deal for Communities Initiative. Public Health. 2004;118:497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boruch RE, Petrosino A, Chalmers I. The Campbell Collaboration: A Proposal for Systematic, Multi-National and Continuous Reviews of Evidence. Background paper presented at: Exploratory Meeting for the Campbell Collaboration; July 15–16, 1999; London, England. Available at: http://www.campbellcollaboration.org.

- 12.Health Development Agency. Evidence and guidance. Available at: http://www.hda-online.org.uk/html/research/index.html. Accessed December 18, 2004.

- 13.Economic and Social Research Council. “The Evidence Network” (ESRC Network for Evidence-Based Policy and Practice) Web site. Available at: http://www.evidencenetwork.org/home.asp. Accessed December 18, 2004.

- 14.Popay J, Williams G, Thomas C, Gatrell A. Theo-rising inequalities in health: the place of lay knowledge. Sociol Health Illn. 1998;20(5):619–644. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connell JP, Kubisch AC, Schorr LB, Weiss C, eds. New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives. Volume 1: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute; 1995.

- 16.Fulbright-Anderson K, Kubisch AC, Connell JP, eds. New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives. Volume 2: Theory, Measurement, and Analysis. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute; 1998.

- 17.Weitzman BC, Silver D, Dillman K-N. Integrating a comparison group design into a theory of change evaluation: the case of the urban health initiative. Am J Eval. 2002;23(4):371–385. [Google Scholar]