Abstract

Advertising has a dual function for British public health. Control or prohibition of mass advertising detrimental to health is a central objective for public health in Britain. Use of mass advertising has also been a more general public health strategy, such as during the initial government responses to HIV/AIDS in the 1980s.

We trace the initial significance of mass advertising in public health in Britain in the postwar decades up to the 1970s, identifying smoking as the key issue that helped to define this new approach. This approach drew from road safety and drink driving models, US advertising theory, relocation of health education within the central government, the arrival of mass consumption, and the rise of the “new public health” agenda.

ADVERTISING IS A KEY SITE of engagement for contemporary British public health. Control of advertising deemed detrimental to population health is an important strategy, as recently demonstrated by the success of efforts designed to prohibit tobacco advertising.1,2 Mass advertising has a paradoxical dual function in public health; while a central cause for concern, it is also a central resource, a strategy used by public health interests and governments. Health campaigns use striking visual and verbal imagery and the full resources of the mass media. In the 1980s, the British Conservative government was prominent for its use of mass media initiatives, most notably its AIDS campaigns, especially the national campaign of early 1987.3,4 The 1980s campaigns focusing on the privatization of state utilities, such as British Gas and British Telecom, also relied on mass advertising. By 1990, the government had become the largest advertiser in the United Kingdom.5

We focus on developments taking place in the United Kingdom to argue that a mass media style of health education had its origin in the redefinition of smoking as a health issue in the period from the 1950s to the 1970s. Redefining smoking was also part of a broader move within public health: the rise of a new ideology that stressed individual responsibility for healthy “lifestyles” and behaviors. The health agenda that grew out of this redefinition involved particular stress on visual techniques of mass persuasion. Its roots lay in American influence, the emergence of mass consumption in the aftermath of wartime restrictions on consumer goods and promotions, and structural changes in responsibility for health, that is, the central–local tension that has characterized much of British health policy.

HEALTH PROPAGANDA FROM THE FIRST THROUGH THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Before World War II, the British government had come to recognize the value of publicity but was reluctant to assume the responsibility of using publicity as a means of dispensing information. In 1919, the newly established Ministry of Health had been given responsibility for dissemination of information about health. Sir George Newman, the ministry’s chief medical officer, recognized that better health would be established through mass education, but publicity was not accepted as a legitimate responsibility of central government until the late 1930s.6 The ministry’s approach depended in part on funding voluntary organizations such as the Central Council for Health Education (CCHE) and working through local government rather than taking action centrally, a tension that has continued to mark efforts to the present day. Commercial methods were discussed, but little use was made of them. This approach subsequently changed, and greater centralization was introduced with the establishment of the Ministry of Information during World War II. However, tensions remained. The early wartime Ministry of Information has been criticized by historians for its “clumsy” and “condescending” publicity arrangements.7 Most of its officials were civil servants who had little experience in terms of publicity work.8

THE 1950S: LOW-KEY AND LOCALIZED

By the time the British Medical Journal published details on the connection between smoking and lung cancer in 1950, responsibility for health education had shifted back to the local level. The initial response to the “discovery” of the connection between smoking and lung cancer in the United Kingdom was low key,9 but this was not simply the result of procrastination. There were certainly links between His Majesty’s Treasury’s reliance on tobacco revenue and the tobacco industry, and the latter funded research through the umbrella of the Medical Research Council.10 But this period of negotiation was also one of “paradigm shift”: the growing acceptability of the epidemiological rather than the biomedical, laboratory-based mode of proof.11,12 It was a period of conflict between different statistical traditions, between the United Kingdom’s dominant genetic and hereditarian tradition and the new approach that emphasized relative risk.13,14 Civil servants in the Ministry of Health debated what form of proof they were dealing with. Was it really conclusive? What forms of health education would be appropriate? A Ministry of Health statement in May 1956 explained why central publicity would not be the correct approach.

The considerations on publicity concerning smoking and lung cancer differ slightly from those on cancer publicity generally in that the special point—that people might give up smoking—is not a matter of reporting symptoms. It does however concern an individual decision which involves others to a very much smaller extent than the subjects of past central public health campaigns.15

Smoking, the ministry argued, was not a “disease” in the same way as cancer or, indeed, infectious disease. It might lead to disease, but not for many years. The notion of long-term “risk” was not part of public health in the 1950s. The publicity approach would involve asking people to curtail a habit that was, at this stage, deeply embedded in everyday culture. It might also raise public fear about cancer, which the ministry had been concerned with damping down. Unfounded cancer phobia might generate a demand for services at a time when National Health Service costs were becoming a political issue.16,17 Publicity would also mean funding the main health education body, the CCHE, which the ministry did not want. After the war, funding responsibility had reverted to the local authorities and away from the central government. The central government had no wish to resume financial responsibility, as discussions at the time make clear.18 Thus, there were practical, structural, and theoretical reasons for the lack of action seen.

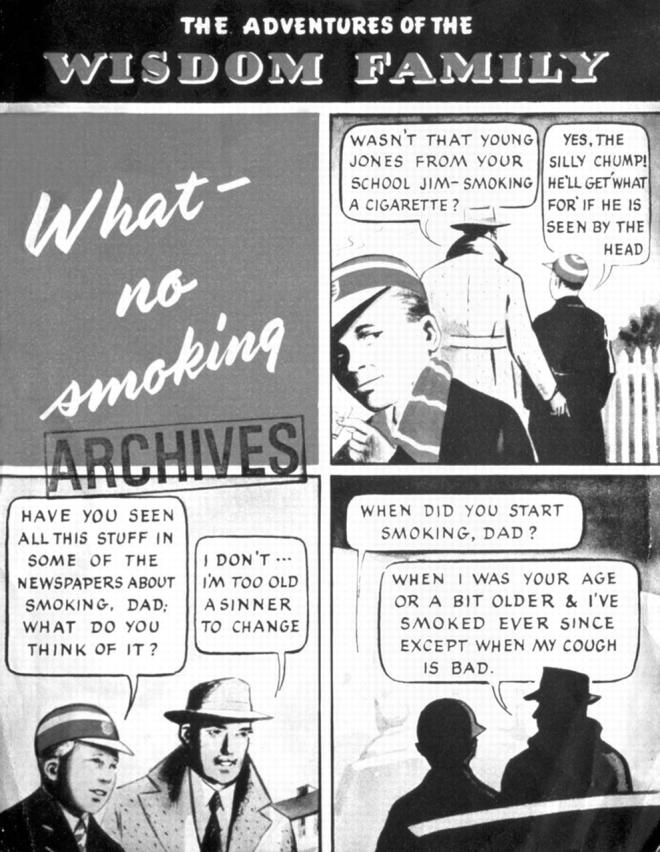

The message that came across in the public education of this period was equivocal. A 1957 pamphlet issued by the CCHE dealt with the adventures of the fictional Wisdom family under the title “What—No Smoking?” In this comic strip, a boy and his mother draw the attention of the smoking father to the risks he is running. Worried, the father goes to see his general practitioner, Dr. Brain, who presents the facts. One in every 300 smokers contracts lung cancer. If he gives up, he is 3 times as likely to get it; if he continues, he is 7 times as likely. Dr. Brain’s advice is measured and calm: “it still does not sound as if the risk is very great, so there’s no need to get in a panic, whatever you decide to do.”19 The idea of outlining specific courses of action to take was anathema to a society that associated “propaganda” with wartime central direction and with earlier Nazi propaganda. Health education placed its faith in the citizenship and responsibility of its recipients.

The scientific message about smoking had not “hardened” at this stage, which could be described as a period of dissent and negotiation before diffusion of an ostensibly stable consensus suitable for public dissemination.20 In the late 1950s, publicity on smoking was the responsibility of the local authorities and of the medical officer of health, the local government public health official. There was no lack of interest. For example, of the 127 representatives of English local authorities who replied to a Ministry of Health circular sent to them in 1958, 118 endorsed the need for local action, and only 9 did not.21 However, with the exception of Edinburgh, only modest action campaigns were initiated. The attitude and personality of the local medical officer of health appeared to have influenced local action as much as anything else. Reports on local responses showed that these reactions varied widely, ranging from a prompt response to situations in which the relevant committee discussed anti-smoking publicity in a cloud of cigarette smoke or the director of education was a heavy smoker and it was recorded that there would be no health education in schools.22

Figure 1.

Pamphlet issued by the Central Council for Health Education in 1957: “What—No Smoking?”

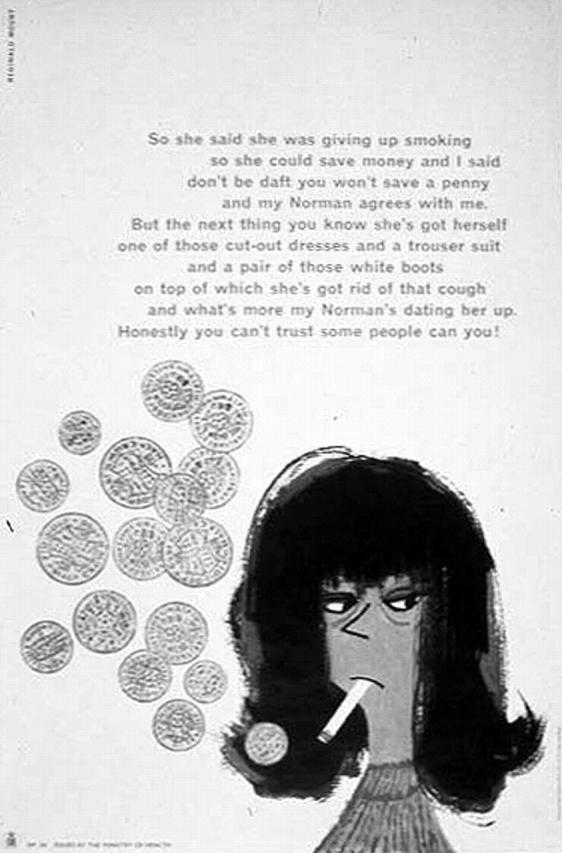

Figure 2.

Poster prepared by Reginald Mount for the Central Office of Information in the 1960s.

THE 1960S: BEGINNINGS OF CHANGE

Within the Ministry of Health, there were the beginnings of a change in stance. An internal paper from the spring of 1960 commented presciently on possible future directions.

It now seems apparent that local health authorities are not likely to be the most effective major agencies for conveying to the adult population information on smoking and lung cancer. Newspapers, magazines, radio and television are the main instruments for informing the public and these naturally look for their sources of news on this subject either to Government announcements or to scientific papers written by researchers in the field.23

Publication of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) 1962 report Smoking and Health led initially to only small signs of change. An advisory group on publicity was set up in the Ministry of Health, and a circular was issued to local authorities offering free publicity. Posters showing coffins and graphs of rising death rates were prominent, and there were also a pair of posters showing a teenage boy and a teenage girl hesitating before they started smoking. A range of materials were produced by other organizations such as the British Temperance Society. A record, “No Smoking,” was produced by Transatlantic Records (“A Scottish psychologist outlines colloquially and effectively the dangers of smoking”).24 The economic dimension of smoking also came increasingly to the fore.

So she said she was giving up smoking as she could save money and I said don’t be daft you won’t save a penny and my Norman agrees with me. But the next thing you know she’s got herself one of these cut out dresses and a trouser suit and [a] pair of those white boots on top of which she’s got rid of that cough and what’s more my Norman’s dating her up. Honestly you can’t trust some people can you!25

The CCHE conducted a “van” campaign in 1962–1963 that disseminated antismoking propaganda throughout the country.26 Four nonsmoking male graduates were recruited to disseminate the message, and they found readier acceptance in schools than in youth clubs or factories. “The girls enjoyed it, they were such charming young men!” wrote the head of one school in 1963. There were reports of a lecture delivered to 3000 schoolchildren in September 1962 at the new Gallery Evangelical Centre in London’s Regent Street. But the focus was still on local authorities, and some medical officers of health took up the cause enthusiastically.

However, the Devon education committee refused to allow leaflets supported by pop stars Cliff Richard and Frankie Vaughan to be distributed in schools. These leaflets were in “beatnik language,” objected a teachers’ representative, and quite contrary to what was being taught. The following is a sample of some of the language reported:

Always puffin’ a fag—squares, Never snuffin’ the habit—squares, Drop it, doll, be smart, be sharp! Cool cats wise, And cats remain, Non-smokers, doll, in this campaign.27

The 1960s began to bring a change in tempo, toward a mass media–focused, slicker advertising agency product pretested through market research. At the same time, the nature and content of the message changed: away from neutral information presentation and reduction of risk toward more direct advice and an absolutist line. This shift was initially evident outside the health field as such. A nationwide Ministry of Transport campaign over the Christmas period in 1964, mounted by the government’s Central Office of Information, sought to change public attitudes toward drinking and driving, informing people of associated dangers and penalties. This short-lived (6 weeks) media blitz involved the use of press, television, and poster advertising and was supported by research on public attitudes and responses before, during, and after the campaign.28 Drunk driving was, in a certain sense, a blueprint for the later smoking and public health media model, and one can trace a process of “policy seepage” as well as one of “policy transfer” from the United States. Here, an initiative developed in one government department, transport, influenced the model subsequently developed in another, health.

Key milestones in the 1960s were the 1962 RCP report, the 1964 Cohen report on health education, and the replacement of the CCHE by the Health Education Council (HEC) in 1968–1969. The 1962 RCP report placed great emphasis on the media presentation of its conclusions in a deliberate move to appear “modern” and to lay out possible policy initiatives to the government.29 Unlike previous reports published by the RCP, it was aimed at the public rather than the medical profession. Production of the report was part of a wider reorientation of medicine and the college itself in the 1960s, a reorientation that saw moves to make RCP’s role more relevant and less distant from society. The secretary of the committee, Dr Charles Fletcher, was well known as a pioneer in media presentation of medicine, and Dr Jerry Morris, another committee member, also placed great emphasis on the importance of discussions of health in the media.30,31 In 2000, at his 90th birthday conference at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, leading epidemiologist Sir Michael Marmot remarked that “Jerry has always told me I should watch more television rather than less.”32

The RCP hired a public relations consultant to manage the report’s launch and held one of its first press conferences.33 The role of the media and of advertising was also given some prominence in the report’s actual content, which recommended restricting rather than banning advertising.34 The government set up a Cabinet committee after the report had been issued, and this committee also discussed mass media campaigns. The role of the media began to seep into the government agenda on smoking. The tobacco industry agreed to a voluntary ban on television cigarette advertising that could appeal to young people, a ban on television advertising before 9 PM, and restrictions on press and poster advertising.35 These developments indicated a new focus on the national media as well as on local action.36

The 1964 Cohen committee took the new tendencies further.37 This committee’s origin lay in lobbying from health educators who sought greater national organization and coordination.38 These educators formed the Institute of Health Education in 1962 and provided evidence to the Cohen committee, claiming that health education techniques represented a synthesis of methods used in “formal education, advertising and PR.”39 The advertising and public relations sections of commercial organizations were presented as a model of effective action and expenditure throughout the committee’s report. The image was one of up-to-date, media-savvy professionals who knew their market. The 1960s were a boom time for advertising and market research in the United Kingdom. Membership in the Market Research Society grew from 23 to 2000 in the years between 1947 and 1972.40 These activities had been curtailed during the war and hampered by the rationing of goods and newsprint into the 1950s. With the birth of commercial television in 1955 and the end of rationing in 1956, Britain entered an era of mass consumption.

“Drunk driving was, in a certain sense, a blueprint for the later smoking and public health media model, and one can trace a process of “policy seepage” as well as one of “policy transfer” from the United States.”

The Cohen committee itself had a strong media membership. Its deputy chair came from the Consumers Association and from a BBC background, while there was also an advertising agency representative and the health editor of Woman magazine. The report advocated dropping the traditional health education focus, which had been on individual advice to mothers regarding specific actions such as vaccination and immunization. The committee members believed that a greater focus was needed on areas associated with human relationships, such as sex education, mental health, the risks of smoking and being overweight, and the need for physical exercise—difficult areas that require “self-discipline.”

A strong emphasis on individual risk avoidance mingled moral and medical imperatives. The belief was that diseases such as chronic bronchitis could be prevented if individuals would modify habits such as smoking and if the government would accelerate its health-promoting campaigns. What was needed was a greater degree of central publicity involving the use of habit-changing campaigns and social surveys as well as efforts to strengthen the new profession of health educators. The models came from American social psychology. The new breed of educators were to be trained in journalism, publicity, the behavioral sciences, and teaching methods. Health education would involve both imparting knowledge and inculcating self-discipline: part of the role of the new health educator was that of a salesperson, persuading people to take appropriate action. Simply knowing about the risks of cigarette smoking was not enough; the Cohen committee labeled tobacco advertising “propaganda,” and the advertising had to be countered in the same way as propaganda.41 This stance was a major change from the even-handed response of the health education profession in the 1950s. Persuasion was now the key.

The Cohen report emphasized the role of the mass media in health education: one television program could reach 5 million people, whereas it would take 250 000 group discussions of 20 people each to do the same. The report led to the establishment of the central government–funded HEC in 1968, which was then reconstituted in the early 1970s.42 By the late 1960s, the impact of these changes had altered the marketing campaign’s approach. In October 1969, a major antismoking poster campaign was launched. There was research input, pretesting, and market evaluation. The campaign was pretested with a statistically selected group of subjects and based on Ministry of Health research published in 1967. An advertising agency was used, and the “look” of the advertisements was quite different from before.

THE 1970S: MEDIA PERSUASION

Expenditures almost doubled on the HEC’s smoking campaign in the early 1970s after a further RCP report in 1971, Smoking and Health Now, and a reconstitution of the HEC itself. Television campaigns and press advertising were areas of growth. £413 899 was spent in 1972–1973 and £702 292 in 1973–1974.43 Research also became more important in the design and evaluation of campaigns. Quantitative sociologist Ann Cartwright had evaluated a campaign carried out in Edinburgh in 1959, and another evaluation had been conducted by sociologist Margot Jeffreys in Hertfordshire in the early 1960s. In the 1960s, this style of research expanded. There was research conducted by the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys on smoking, along with surveys conducted by educationalist John Bynner (on smoking among boys) and public health researcher Walter Holland (on the impact of health education on schoolchildren).44 The social survey found a role in health education through the smoking issue.

The advertising agency Saatchi and Saatchi mounted the new-style advertising campaign for the HEC. Saatchi’s campaign emerged from the reconfiguration of advertising in the United Kingdom in the 1960s and under the influence of developments taking place in the United States. Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders was published in 1957, and Charles Saatchi visited the United States in the early 1960s.45,46 Saatchi recalled how the press advertising people dominated the UK advertising scene, with little knowledge of the possibility of television. The new-style agencies changed the image of advertising and began calling in academics to help; the result was a more professional scientific approach that also typically involved a combination of humor and hard sell. Cigarette advertisements, such as the Gold Box Benson and Hedges advertisements created by the Collett Dickinson and Pearce agency, were among the first to use this approach.

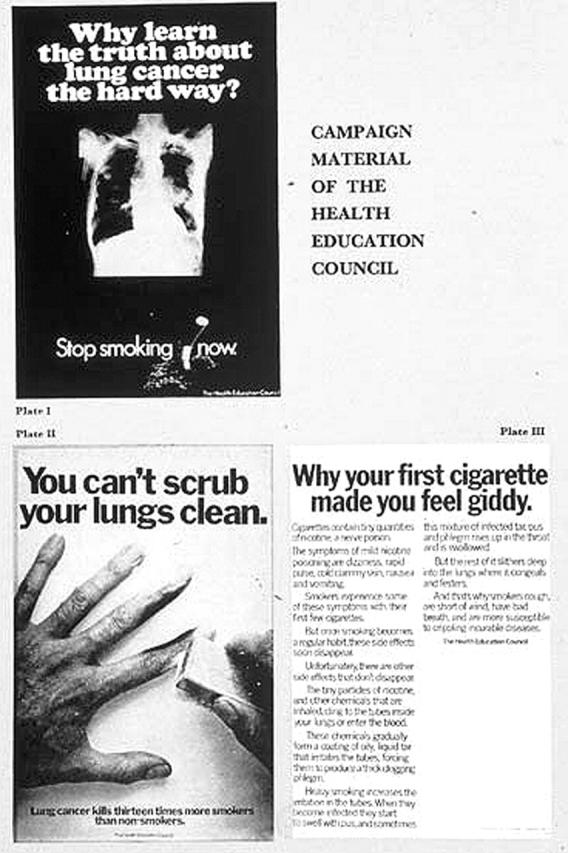

The HEC account was Saatchi’s first big break, and it marked the importation of the new advertising style into the ranks of the public health opposition. At first, the work was confined to posters and brochures, but later came full-scale advertising. Saatchi produced a number of advertisements early in 1970 with such content as “The tar and discharge that collect in the lungs of the average smoker” and “You can’t scrub your lungs clean.” These images generated an anti-aesthetic around smoking; visible effects, such as unsightly nicotine stains on fingers, provided a visual cue to deeper, more significant damage. The rest of the media started to become interested. The Sun newspaper wrote about the anti-smoking campaign, noting how dynamic and brutally effective the copywriting was. Earlier hesitations about generating public fears concerning cancer were swept aside. Graphic images of diseased lungs were featured in posters such as one asking “Why learn the truth about lung cancer the hard way?”

In 1970, the Saatchi brothers formed the Saatchi and Saatchi agency, and Charles Saatchi brought the HEC account with him. For the first time, the anti-smoking campaign was extended to television. Advertisements in 1971 showed smokers crossing London’s Waterloo Bridge intercut with film of lemmings throwing themselves off a cliff. A voice-over said: “There’s a strange Arctic rodent called a lemming which every year throws itself off a cliff. It’s as though it wanted to die. Every year in Britain thousands of men and women smoke cigarettes. It’s as though they want to die.”47

There began to be a change of focus to target women, pregnant women especially. In 1957, the fact that education would have to be directed to men, as the main group of smokers, was considered by the Ministry of Health to be another reason not to make smoking the subject of a major campaign; it just did not fit the public health and health education stereotype.48 Women reemerged in the 1970s as a major focus of health education regarding smoking, as part of the focus on individual behavior that reproduced public health’s concern for women as social hygiene 70 years earlier and added new concerns about reproduction in the “pill era.”49

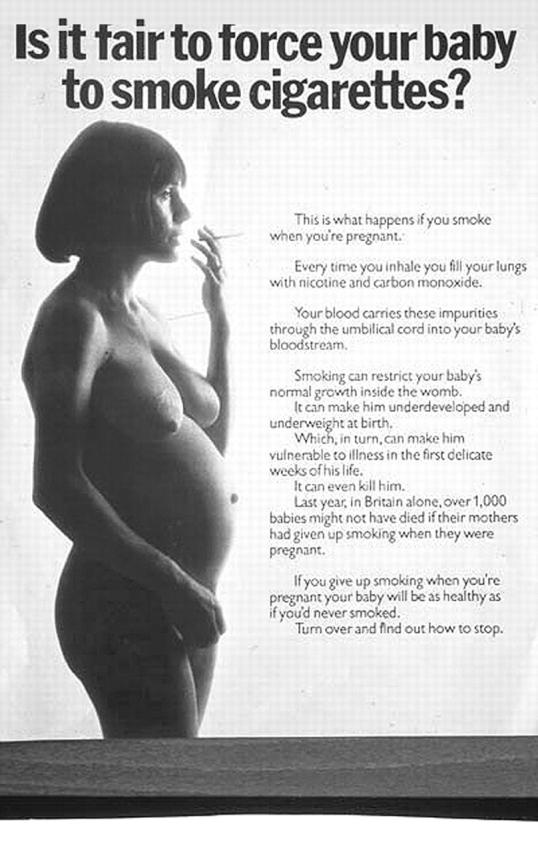

The most striking image from a campaign run in 1973–1974 was one of a naked, pregnant, smoking woman. “Is it fair to force your baby to smoke cigarettes?” the poster asked. There was a clothed version of the woman, but evaluations of this version led to the conclusion that it was less effective as a campaign tool.50 The HEC’s main preparatory research for the campaign had been based on a clothed model and had not used the nude option. Alistair Mackie, head of the HEC, later explained that the nude emerged out of a conversation he had with his chief medical officer: “I can remember thinking in a crude way what a tremendous topic this was for public relations work.”51 Public images of female nudity were not common in the advertising culture of the time, and a nude image of a pregnant woman had obvious shock value. The poster enhances this impact through its portrayal of the woman as serene, unconcerned, or possibly simply unaware. Indeed, if the image is reduced and we see the head and shoulders only, the smoking woman would not be out of place in a cigarette advertisement.

The campaign cost £160 000 and consumed nearly two thirds of the HEC’s antismoking budget for the year. Two further campaigns were planned, and more than 20% of the HEC’s anti-smoking budget was to be allocated to smoking in pregnancy. Some critics disputed the resulting effects. Surveys commissioned by the HEC before and after the first campaign showed that the percentage of pregnant women who smoked fell from 39% to 29%. This reduction seemed significant, but the research was flawed because it had not compared pregnant women who watched the advertisements with a control group of pregnant women who did not.

Figure 3.

(Left) Advertisements produced by Saatchi’s for the Health Education Council in 1970. (Right) The naked smoking mother poster produced by Saatchi’s in the 1970s.

Similar HEC research on later campaigns showed no overall impact and revealed that 15% of women stopped smoking spontaneously anyway when they became pregnant.52 Women were the focus, but there was no doubt that the at-risk fetus was male. According to the HEC press release for the second pregnancy campaign, “Mums-to-be will be told that smoking can restrict the baby’s growth, make him under-developed and underweight at birth and even kill him” [italics added].53 There was also a focus on preventing teenagers from initiating tobacco use. The pregnant woman campaign paralleled Saatchi’s campaign for the HEC on contraception, wherein a picture of a doleful pregnant man was captioned “Would you be more careful if it was you that got pregnant?” In the 1970s, the smoking problem was defined in accordance with women in their reproductive role, although there was little evidence that this was in fact the major issue. Smoking was failing to decrease among women and young girls in general, not just pregnant women.54

Even though the subject matter was traditional in its “women as mothers” emphasis, the style and nature of these advertisements, along with their use of television as well as traditional poster campaigns, were departures. The message of the advertisements also took a new, harder line. The 1950s Wisdom leaflet left it up to the individual to decide. Others advised a harm reduction approach through switching to safer forms of tobacco use such as smoking pipes and cigars. By the end of the 1970s, the HEC had begun to promote a definite style of behavior change. In 1978, the council responded to a report produced by the government’s Independent Scientific Committee on Smoking and Health. The committee’s report focused on product modification and lower-risk (sometimes called “safer”) cigarettes. The council’s advertisement on the topic stated that switching to a substitute cigarette was like jumping from the 36th rather than the 39th floor of a building. This graphic illustration of risk signaled the end of the more liberal policy line that had been followed since the 1950s.55

This change in the health education “view” can be linked to 2 developments, one smoking specific and the other related to overall changes in public health ideology and practice. So far as smoking was concerned, the 1970s had been occupied at the governmental level with moves to work with industry to develop tobacco substitutes or remove the harmful components of tobacco and produce a “safer cigarette.” The publication of the 1978 report led to a barrage of criticism; seasoned smoking researchers argued that its proposals for reduced tar and nicotine cigarettes could lead to “compensatory smoking,” with the smoker inhaling more harmful products rather than fewer such products. The harm reduction agenda for smoking was under threat.56

The wider public health agenda was also changing by the end of the 1970s. Smoking formed part of this redefinition and, in fact, epitomized it. At the international level, documents such as the Lalonde report (1974) had stimulated new thinking about public health, while in the United Kingdom this agenda was underlined by the government’s publication of Prevention and Health: Everybody’s Business at the end of the 1970s.57 “Everybody’s business” implied individual and community responsibility rather than the previous emphasis on the role of state intervention or clinical facilities and services. In the United Kingdom, this came not long after the removal of medical public health practitioners (medical officers of health) from their local authority bases and into clinical health services.58 The old local health education model, dominated by the medical officer of health, was undermined at the structural level at the same time as the ideology of public health itself was changing.

Despite the Cohen committee’s emphasis on the new breed of health educators, there were initially few at the local level, approximately 50 in the mid-1960s.59 The new policy agendas—emphasizing smoking but also a host of other health issues (such as diet and heart disease)—were typically underpinned by epidemiological research and social surveys and focused on behavior change, on the culpable role of industry, and on the use of taxation or other economic incentives as a health tool. Above all, there was a media agenda with a dual focus.

Advertising was a key site of engagement with the industrial “opposition.” The media began to suffuse a new style of health activism. Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), established in 1971, exemplified this approach. This led to some initial problems for the new organization. In its launch leaflet, ASH had envisaged that it would itself undertake an advertising campaign. Its goal was to drop the “black widow” approach of the road accident campaigns, which had aimed to shock drivers into responsible behavior. Instead, it envisaged marketing social acceptability. Financial and material incentives were to be encouraged, with group therapy along the lines of Weight Watchers and a focus on children and young people. “Primarily the campaign will attempt to take the social cachet that surrounds smoking and turn it on its head.”60

However, the ASH proposals ruffled feathers, because the ideas outlined infringed on the territory of the HEC. The HEC was annoyed at the overlap with its role. ASH subsequently defined its public role around effective media “spin” in a way that did not involve so much of a direct marketing role.61 But the fact that both it and the HEC had reached similar conclusions about health marketing in the early 1970s is a striking illustration of the overall change toward media persuasion during that period.

“Hidden persuasion” was used, from the feminist perspective, to characterize women as “victims” of mass advertising. In The Lady-killers: Why Smoking Is a Feminist Issue, an influential public health text of the early 1980s, ASH Deputy Director Bobbie Jacobson characterized women as the passive “dupes” of mass media messages about smoking.62 This implied a role for the media that drew on the Frankfurt school of media sociology, which had stressed the role of citizens as receptors of the influence of mass media.63

In the United Kingdom, American commercial techniques of education and persuasion exerted an impact on public health professionals, in terms of their location and role, at a time of structural change. In France and Switzerland, too, the role of psychological and mass media models grew in importance; France also set up a centralized agency in the late 1970s.64 In Switzerland, the route initially came via advertising in the occupational health field and through road safety; in Britain, too, road safety seems to have been the precursor. The mass media were “modern,” and thus, in regard to public health in the United Kingdom, they were part of its modernizing project.65

Their use was also part of a redefined consumerism linked to developments in health advertising. As mentioned, the Consumers Association was represented on the Cohen committee, and it was this association that published the first report in 1971 on tobacco labeling. Stacey has argued that the health consumer as a concept originated in the 1970s.66 Three decades later, mass communication remains a widely used strategy. Social marketing in health promotion attests to the importance of consumerism and persuasion in health. For the tobacco field, advertising retains its symbolic status, and controversy over “effect” has had little impact on that.

Research into the effectiveness of mass communication strategies in health promotion has discounted older “injection” models of media effect and concluded that production of behavior change is unproven. However, media coverage can define the framework of a public agenda.67 Recent UK policy commentary has criticized the concentration on mass advertising techniques as of little proven impact, although they retain political utility.68 In commercial advertising, the pendulum is now swinging toward individual, personalized advice, and it remains to be seen whether health promotion marketing will follow suit.69 Understanding the historical rationale for the emergence of mass advertising in public health during the 1970s could help inform reassessments of strategies in the present.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Wellcome Trust, which funded the historical work on which this article is based.

Our thanks are due to Wendy MacDowall of the Sexual Health Programme, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who provided advice on current views of “media persuasion” in health promotion.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors Virginia Berridge carried out the research on smoking and wrote the article. Kelly Loughlin commented on the article and wrote new material based on her research on mass media health education.

Endnotes

- 1.“Campaigners Hail Tobacco Ad Ban,” Guardian, February 14, 2003.

- 2.Control or prohibition of candy advertising during children’s television programs is currently under discussion. See “Curb on Junk Food Adverts to Combat Child Obesity,” Guardian, December 1, 2003.

- 3.They employed “shock–horror” tactics (e.g., “AIDS, Don’t Die of Ignorance”) and made extensive use of television; advertising agencies and market research companies were involved as well. See V. Berridge, AIDS in the U.K.: The Making of Policy, 1981–1994 (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1996).

- 4.An anti-heroin campaign mounted in 1985–1986 had been a precursor of the later AIDS campaign. It proved controversial with researchers, who argued that mass media might be counterproductive and that the market research campaign evaluation had not been rigorous. See N. Dorn, “Media Campaigns,” Druglink 1 (1986): 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams K., Get Me a Murder A Day! A History of Mass Communication in Britain (London: Arnold, 1998), 255.

- 6.Grant M., Propaganda and the Role of the State in Inter-War Britain (Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1994).

- 7.Grant M., Propaganda, 245.

- 8.Taylor P. M., The Projection of Britain (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 291–292; P. M. Taylor, “Techniques of Persuasion: Basic Ground Rules of British Propaganda During the Second World War,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 1 (1980): 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster C., “Tobacco Smoking Addiction: A Challenge to the National Health Service,” British Journal of Addiction 79 (1984): 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berridge V., “Science and Policy: The Case of Post War British Smoking Policy,” in Ashes to Ashes: The History of Smoking and Health, eds. S. Lock, L. Reynolds, and E. M. Tansey (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1998), 143–163. [PubMed]

- 11.Burnham J., “American Physicians and Tobacco Use: Two Surgeons General, 1929 and 1964,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 63 (1989): 1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandt A., “The Cigarette, Risk and American Culture,” Daedalus Fall (1990): 155–176.

- 13.Berlivet L., “Association or Causation? The Debate on the Scientific Status of Risk Factor Epidemiology, 1947–c.1965,” in Making Health Policy: Networks in Research and Policy Since 1945, ed. V. Berridge (Amsterdam: Rodopi, forthcoming). [PubMed]

- 14.Parascandola M., “Cigarettes and the US Public Health Service in the 1950s,” American Journal of Public Health 91 (2001): 196–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Tobacco smoking and cancer of the lung. Brief for adjournment debate March 1, 1957. MH55/2220.

- 16.Cantor D., “Representing ‘the Public’: Medicine, Charity and Emotion in Twentieth-Century Britain,” in Medicine, Health and the Public Sphere in Britain, 1600–2000, ed. S. Sturdy (London: Routledge, 2002), 145–168.

- 17.Webster C., “Tobacco Smoking Addiction, 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Public health propaganda; smoking and lung cancer: publicity policy, 1957–1960. MH55/2203.

- 19.Health Education Authority leaflet archive. “The Adventures of the Wisdom Family: ‘What—No Smoking?’ ” Central Council for Health Education leaflet, 1957.

- 20.On the processes through which public statements about scientific advice are provided to nonscientific audiences, see S. Hilgartner, Science on Stage: Expert Advice as Public Drama (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000).

- 21.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Summary of local health authority replies to circular 17/58. MH 55/2225.

- 22.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Publicity-action taken by local authorities 1957–8. MH55/2228.

- 23.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Paper to Mr Galbraith on smoking and lung cancer. March 15, 1960. MH55/2226.

- 24.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Correspondence re proposal for two mobile units. MH 82/205.

- 25.Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine. Iconographic Collection. A young woman smoking, with silver coins representing the expense of buying cigarettes. Color lithograph, London: Central Office of Information, n.d. One of a pair of posters with a similar poster of a man. Photo no. L24904.

- 26.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Files on the mobile unit campaign. MH 82/205–82/209.

- 27.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Smoking and health campaign policy. Daily Mail report. February 22, 1963. MH 151/18.

- 28.The research was carried out by the Road Research Laboratory and the campaign organized by the Advertising Division of the Central Office of Information, which drew on the services of commercial advertising companies. See F. Clark, The Central Office of Information (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1970).

- 29.Royal College of Physicians. Committee to report on smoking and atmospheric pollution. Minutes of fourth meeting. March 17, 1960.

- 30.Booth C. C., “Smoking and the Gold Headed Cane,” in Balancing Act: Essays to Honour Stephen Lock, ed. C. Booth (London: Keynes Press, 1991).

- 31.Loughlin K., “ ‘Your Life in Their Hands’: The Context of a Medical-Media Controversy,” Media History 6 (2000): 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Transcript of witness seminar for 90th birthday of Jerry Morris, July 21, 2000, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/history (accessed April 12, 2005). See also V. Berridge, “Jerry Morris,” overview for special issue of International Journal of Epidemiology 30 (2001): 1141–1145; K. Loughlin, “Epidemiology, Social Medicine and Public Health: A Celebration of the 90th Birthday of Professor J. N. Morris,” International Journal of Epidemiology 30 (2001): 1198–1199.11689537 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Interview with public relations consultant conducted by Virginia Berridge, 1995.

- 34.Royal College of Physicians, Smoking and Health (London: Pitman, 1962).

- 35.Agreement on these restrictions was reached through the Office of the Postmaster General, which was charged with regulating television advertising.

- 36.By the 1960s, television had joined the press as a key media player in Britain. The one BBC channel in the 1950s was joined by a commercial channel in 1955. The BBC gained a second noncommercial channel in 1963. In 1958, income from television advertising exceeded that from the press for the first time. See K. Williams, Get Me a Murder a Day!, 217–219.

- 37.Ministry of Health, Central Health Services Council, Scottish Health Services Council. Health Education: Report of a Joint Committee of the Central and Scottish Health Services Councils (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1964).

- 38.Blythe G. M., A History of the Central Council for Health Education, 1927–1968 (unpublished Master of Literature thesis, Oxford University, 1987).

- 39.Health Education, 95.

- 40.Williams, Get Me a Murder a Day!, 217.

- 41.Health Education, 14, 46.6443896

- 42.The World War II and postwar history of health education up to the 1980s is surveyed in R. Smith, The National Politics of Alcohol Education: A Review (Bristol: School of Advanced Urban Studies, 1987), 1–21. See also G. M. Blythe, A History of the Central Council.

- 43.HEC smoking and health campaign activities, c.1975. Typescript document in HEA information center collection.

- 44.Walter Holland, interview conducted by M. A. Miller. Oxford Brookes University/Royal College of Physicians video interviews, May–December 1996; Walter Holland, interview conducted by V. Berridge, March 1997; J. M. Bynner, Medical Students’ Attitudes Towards Smoking: A Report on a Survey Carried Out for the Ministry of Health (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1967); J. M. Bynner, The Young Smoker: A Study of Smoking Among School Boys Carried Out for the Ministry of Health (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1969).

- 45.Packard V., The Hidden Persuaders (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1957).

- 46.Fendley A., Commercial Break: The Inside Story of Saatchi and Saatchi (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1995).

- 47.Quote from Fendley, Commercial Break, 35.

- 48.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. Publicity: statement by the MRC and Ministry of Health, 1955–58. April 1, 1957. MH55/2220.

- 49.As discussed in J. Lewis, The Politics of Motherhood: Child and Maternal Welfare in England, 1900–1939 (London: Croom Helm, 1980). See also L. Marks, Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), chap. 8.

- 50.Evidence by Department of Health witnesses presented to the Select Committee on Preventive Medicine, 1976, in First Report from the Expenditure Committee: 1976–77 Session (London, 1977), 2137–2138.

- 51.Jacobson B., The Ladykillers: Why Smoking Is a Feminist Issue (London: Pluto Press, 1981), 72.

- 52.ASH archive, Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine. William Norman collection, SA/ASH Box 77, R. 14. Alister Mackie file. Anti-Smoking in Pregnancy Campaign: Pre and Post Campaign Study (Communication Research, 1974, 1975). Also cited in B. Jacobson, The Ladykillers.

- 53.ASH archive, Wellcome library. William Norman collection, SA/ASH Box 77, R. 19. Alistair Mackie file.

- 54.Berridge V., “Constructing women and smoking as a public health problem in Britain, 1950–1990s,” Gender and History 13 (2001): 328–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Health Education Council. Annual report, 1977–1978.

- 56.Berridge V., “Science and Policy.” See also V. Berridge and P. Starns, “The ‘Invisible Industrialist’ and Public Health: The Rise and Fall of ‘Safer Smoking’ in the 1970s,” in Medicine, the Market and the Mass Media: Producing Health in the Twentieth Century, eds. V. Berridge and K. Loughlin (London: Routledge, forthcoming).

- 57.Petersen A. and D. Lupton, The New Public Health: Health and Self in the Age of Risk (London: Sage, 1996).

- 58.Lewis J., What Price Community Medicine? The Philosophy, Practice and Politics of Public Health Since 1919 (Brighton: Wheatsheaf, 1986).

- 59.Blythe M., “A Century of Health Education,” Health and Hygiene 7 (1986): 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Archives. Ministry of Health papers. MH 154/169. Letter from John Dunwoody to Julia Dawkins. January 5, 1971.

- 61.Berridge V., “New Social Movement or Government Funded Voluntary Sector? ASH (Action on Smoking and Health) Science and Anti Tobacco Activism in the 1970s,” in The Practice of Reform in Health, Medicine and Science, 1500–2000, eds. M. Pelling and S. Mandelbrote (London: Ashgate, forthcoming).

- 62.Jacobson, The Ladykillers.

- 63.Curran J. and J. Seaton, Power Without Responsibility: The Press and Broadcasting in Britain. 4th ed. (London: Routledge, 1991).

- 64.On French health education, see L. Berlivet, “Uneasy Prevention: The Problematic Modernization of Health Education in France After 1975,” in Medicine, the Market and the Mass Media: Producing Health in the Twentieth Century, eds. V. Berridge and K. Loughlin (London: Routledge, forthcoming); on Switzerland, see M. Lengwiler, “Between War Propaganda and Advertising: The Visual Style of Accident Prevention as a Precursor to Post War Health Education in Switzerland,” in Medicine, the Market and the Mass Media.

- 65.Royal College of Physicians. Minutes of the Committee on Smoking and Atmospheric Pollution, fifth meeting, January 4, 1961. “It was agreed that the report should include a section on the use of advertising against smoking[;] modern methods should be employed to combat modern methods.”

- 66.Stacey M., “The Health Service Consumer: A Sociological Misconception,” Sociological Review Monographs 22 (1976): 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.For a recent discussion of the effects of the mass media, see D. Reid, “How Effective Is Health Education via Mass Communications?,” Health Education Journal 55 (1996): 332–344; S. Ellis and A. Grey, Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs): A Review of Reviews Into the Effectiveness of Non-Clinical Interventions (London: Health Development Agency, 2004); K. Wellings and W. MacDowall, “Evaluating Mass Media Approaches,” in Evaluating Health Promotion: Practice and Methods, eds. M. Thorogood and Y. Coombes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- 68.See, for example, G. Edwards, P. Anderson, T. F. Babor, et al., Alcohol Policy and the Public Good (Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 1994), 172–175.

- 69.The alcohol industry is currently experimenting with personal recommendation as a marketing technique, whereby promoters befriend and advise partygoers on what drink to buy.