Abstract

Music has long been a uniting force among workers. Music can improve team spirit and provide an enjoyable diversion, but it is most useful in expressing the true feelings of a sometimes desperate community.

Over time, a variety of musical media have emerged to match the prevailing conditions at work: the folk songs of 19th-century handloom weavers, the songs of industrial Britain’s trade union members, the workers’ radio programs of the 1940s.

Associations have arisen to encourage and coordinate musical activities among workers, and public awareness of the hazards of some occupations has been promoted through music.

Music has a power unlike anything else. It is present in all cultures and societies, through happiness and hardship. Music crosses all boundaries and unites members of every walk of life, but none more than workers. Music in the workplace is likely to have been present in the earliest societies. It can be beneficial for alleviating the monotony of repetitive labor. There is no clearer illustration of this than the classic scene from the Walt Disney movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in which that loveable septet sings “Whistle While You Work.”

Sundstrom summarizes the limited research available that examines the benefits of music in the workplace.1 Music motivates workers, and many workers find music enjoyable. It decreases boredom and leads to increased productivity, perhaps partially because people work in time with the beat. There is some evidence that music is associated with a decrease in errors in manufacturing.1 Music is said to improve perfomance by increasing psychological arousal, and vigilance.2–5 Finally, making or listening to music can increase psychological well-being, so although music may not be directly responsible for preventing accidents it can certainly have beneficial effects on mental health and mood.6

The history of occupational health includes many horrific stories that highlight the dangers of bygone practices. Workers sometimes found themselves trapped in the rapidly spinning leather straps of Victorian factories. Small children lost digits trying to extract objects blocking the machinery’s cogs. Miners breathed in stone dust and later developed silicosis.7–9 Over time, many safety features have been designed to minimize health hazards and accidents in the work-place. Nevertheless, workers’ psychological state is always a consideration, and this is where music fits into the history of occupational health.

MUSIC AS PASTIME

Some European composers are celebrated for drawing upon the folk music of their countries, such as the 19th-century Czech Bedr ich Smetana and the early 20th-century Hungarian Béla Bartók. However, before the Industrial Revolution other genres of music were just as common as folk music in rural communities. Elbourne notes that in some English communities not only was folk music popular, but so were religious hymns and music by Handel.11 The performers of such works were often laborers, including handloom weavers in Lancashire.11 These early 19th-century weavers were always “singing away to the click of the shuttle”11(p14) and even developed “a rather saucy type of song.”11(p6) Child laborers, who were endeavoring to finish their work before the Christmas holiday, would sing hymns and carols “incessant during the day” to prevent themselves from falling asleep.11(p14)

In the days before the dark clouds of the Industrial Revolution descended, laborers could work from home and pursue their musical hobbies too.10 Some even “made music a special study.”11(p15) The workers would meet in each others’ homes or public houses to sing solo or in groups. Furthermore, “[t]hese worthy men made a large sacrifice of time and labour in the cultivation of music, principally for the love of music.”11(p15)

SONGS FOR THE WORKERS’ UNIONS

Singing in factories would soon end, as the noise of the Industrial Revolution’s machines drowned out the human voice. As Sundstrom notes, some of the quieter industries did try to boost morale by hiring women to sing among the workers.1 Other industries hired company orchestras and formed glee clubs so that the workers could at least enjoy some positive experiences.1

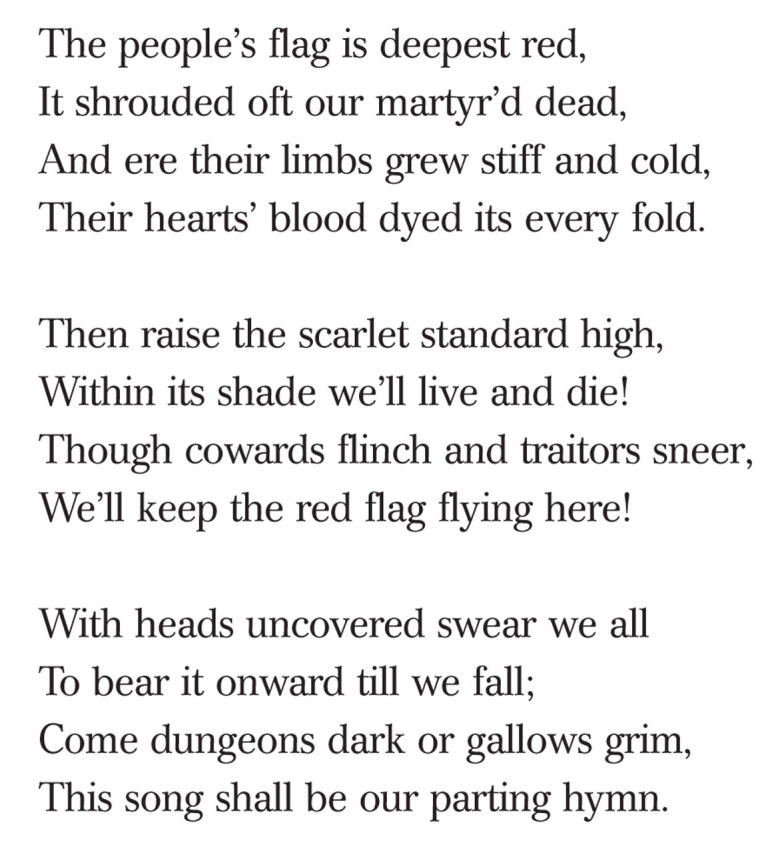

Some trade union songs have been traced to the 19th century, particularly those of agricultural workers. Such songs as “Stand Like the Brave” encouraged laborers “to join the Union and fight for better conditions.”12(p8) The great London dock strike of 1889 was a successful cry from the unskilled laborers who had struggled to retain secure jobs alongside their more skilled counterparts. Subsequently, trade unions spread and broadened their support, indiscriminately, for all groups of workers.10 Many songs grew in response to this flourishing trade union movement, including “The Red Flag.”

The railway industry also developed a satirical repertoire. Ward, for example, says that the “isolation and loneliness [and] long hours” of railway workers allowed “periods for reflection” and the “high risk of death and mutilation” among railway workers prompted a body of song to rival that of miners and weavers.13(p13) He also mentions the high rates of accidents and deaths suffered by railroad guards, shunters, and way men, which resulted in such song themes as “Don’t say you heard it from me,” “Only one killed,” and “Done to death.”13(p15) There was, not surprisingly, much political censorship of these songs, which were highly critical of the railway companies. For the workers themselves, it was often the case that “to sing meant the sack.”13(p15)

MUSICAL ORGANIZATIONS

Music at work seems to have become less common as industries grew. This decline must have been the impetus for the foundation of labor bands and choirs who no doubt rehearsed during their leisure time. In some cases, these groups were highly successful. Perhaps most popular were the colliery brass bands, which often performed in concerts and competitions and achieved extraordinary levels of excellence. Unions and associations arose to organize these ensembles.

The Workers’ Music Association (WMA), founded in 1936, was initially formed to coordinate the musical activity of workers who were members of some 44 choirs and 5 orchestras in the London Choral Union and Cooperative.14,15 The WMA itself was rooted in communism; many in this group, including its founder and longtime president, composer Alan Bush (1900–1995), were members of the British Communist Party.15 However, this political leaning was probably a reflection of the times; the Soviet Union had entered the war, and a sense of “friendship was fostered” by the fact that the Soviet Union “was an ally against Fascism.”15 Consequently, the British developed a fresh interest in Russian music.15

The WMA successfully promoted Soviet culture through songs, concerts, lectures, and publications.15 Many booklets of songs, in fact quite “a respectable library of propaganda music,”14(p4) were published for the use of the WMA’s choirs and the public (Figure 1 ▶). Best sellers included Popular Soviet Songs (selling more than 20 000 copies) and Red Army Songs, both published during World War II, as well as the Pocket Song Book (1948) and The Shuttle and Cage (1954).14

FIGURE 1—

“The Red Flag,” a socialist British labor anthem that reflects on the solidarity of this movement during adversity, was inspired by the great London dock strike of 1889 and has remained popular to this day.12

Source. 48 Songs: Community Singing.16

In 1940, the WMA founded the Topic Record Club to distribute records of popular workers’ songs (including those of new Soviet composers) to its members each month.14 WMA members also formed their own musical ensembles, performing concerts to benefit the war effort, trade union members, other war workers, and the armed forces.14 Direct participation in music-making usually provides a higher level of satisfaction than simply listening to music. Therefore making music is an effective way to allay one’s worries and fears, lessen the burden of responsibility, and achieve a sense of refreshment before returning to the “real world.”

The value of the WMA did not end with World War II. In 1960 and 1961, the variety of trades and professions attracted to the WMA was diverse, including “[e]ngineers, miners, teachers, medical students, electricians, clerks, printers . . . and a euphonium-playing plumber.”17(p8) The WMA exists to this day, although much of its work now focuses on promoting musical education among the public.

THE NEW MEDIUM: RADIO

During World War II, the radio was essential for instantly disseminating information. It was often the harbinger of doom, but it was also a source of comfort for many. On June 23, 1940, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) first transmitted a radio program that would run for 27 years: “Music While You Work.” It was a twice daily, half-hour program of music “meant specially for factory workers to listen to as they work.”18(p3) Many people can still recall the famous theme song of this program, “Calling All Workers.”

The BBC explained its dramatic rescheduling of programming in the article “Radio in Wartime: Should It Be Grave or Gay?”18 The BBC realized that radio had grown in popularity because new listeners tuned in particularly for the news.18 Therefore, such programs as racing results and sporting commentaries were discontinued in order to be sensitive to “the prevailing mood of the nation.”18(p3) Because “some say that they are giving long hours to war-work and they look to radio for amusement and diversion to refresh them and help them to carry on,”18(p3) the BBC scheduled Music While You Work at midmorning and midafternoon, where one might expect a dip in concentration.19

No recording of any early episode of Music While You Work remains in the archives, but the schedules suggest that a wide variety of music would have catered to most tastes. The program featured dance bands playing popular, high-spirited music of the time.20 The very first program featured the Organolists, who played the organ, drums, and piano.21 Some cheaper, yet no doubt popular, programming alternatives included “music of the films, on record.”18(p16)

Geiger and his orchestra, comprising a cello, violins, bass, and Hungarian cimbalon, were frequent contributors,22 performing love songs, folk dances, and waltzes by Strauss.23 This lively combination helped workers get through their shifts.

The bands were instructed to play medleys rather than individual tunes, in order to keep the workers’ attention.20 Furthermore, the musicians were to keep pace with the “rhythms of the workbench” so that production would not slow down.20(p23) In 1942, the song “Deep in the Heart of Texas” was banned from the program because it contained a participatory handclapping section that tempted laborers to stop work and join in.20

Music While You Work probably minimized the occurrence of accidents by improving alertness and team interaction. The minister of labor, in 1940, wrote that the program also “made the hours pass more quickly and resulted in increased production.”24(p60) In fact, some participating factories during the war noted a 20% increase in production.24 This trend was soon recognized by others. In the late 1950s the company Muzak was formed; it provided music to be played in offices to “subtly stimulate employees during times when they otherwise worked slowly.”1(p170)

MUSIC FOR PUBLICITY

During the 1950s and 1960s, 8 radio documentaries were produced by Charles Parker, former WMA member and BBC employee. The documentaries include many tape-recorded accounts from workmen of the time, as well as some renditions of traditional workers’ folk songs.25 Many of the program’s themes were set to music by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger, who “were at the forefront of the British folksong revival.”25 In fact, MacColl and Seeger regularly recorded folk music for Topic—the WMA’s own record label—which has been called “the significant disseminator for a growing folk network.”15 Together, Parker, MacColl, and Seeger created a new genre termed the “radio ballad.”25

One of these productions, Big Hewer, was transmitted on the BBC Home Service on August 18, 1961.25 This documentary told the story of Britain’s coalminers’ experiences. One section begins with the words “Coal is a thing that’s cost life to get,” and from then on the listener is presented with many accounts of ill health and death in the coal mines: “You’re eating coal, you’re breathing coal,” “reduced to nothing . . . no lungs to breathe,” “he’s worked in the pits since he was . . . twelve year old . . . he’s got inside his lungs a good tombstone, of solid coal-dust.”26 The documentary continues in this fashion, highlighting issues such as compensation and safety in the hope of remedying the appalling conditions. The workers also speak of new machinery, better conditions, and better pay.

In contrast to the traditional folk music of workers, Big Hewer’s aim was to educate the public about issues that, at the time, were as remote to the researchers themselves as to the public. MacColl writes that for Parker, meeting the miners was a “shattering experience.”27 Parker “confessed to feeling utterly uneducated in the presence of [the] miners” and his Panglossian “view that everything is all right in the best of all possible worlds” was soon dashed.27 The radio ballad summed up the stark reality of the coal miner’s life, but it also demonstrated the sense of unity and pride among these workers.

CONCLUSION

The associations between music and work are interesting and important. The folk tradition within the workplace was drowned out by the noise of the Industrial Revolution. When workers could no longer sing at work, they formed union ensembles and performed during their leisure time. During World War II, music was piped into the workplace to keep up morale and enhance production.1,18,20 Later in the 20th century, music took on a new role, becoming a medium through which the public could be educated and informed about the conditions of workers.25

Music in the workplace has increased efficiency, lifted spirits, and even bound society together. Music still does all of this, and it is one force that can help carry us forward into the future.

Acknowledgments

I thank Robert Arnott, director, and particularly Jonathan Reinarz, Wellcome research fellow, at the Centre for the History of Medicine, University of Birmingham Medical School, for their encouragement and critiques of earlier versions of this article. I am grateful to the staff at the Birmingham City Archives in the Birmingham Central Library for allowing me access to the Charles Parker Archive. Finally, many thanks to John Jordan, conductor and archivist at the Workers’ Music Association, for kindly providing me with copies of some interesting material that relates to the archive.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Sundstrom E. Music. In: Work Places: The Psychology of the Physical Environment in Offices and Factories. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1986:167–178.

- 2.Zimny GH and Weidenfeller EW. Effects of music upon GSR and heart-rate. Am J Psychol. 1963;73:311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davenport WG. Arousal theory and vigilance: schedules for background stimulation. J Gen Psychol. 1974;91(4): 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox JG and Embrey ED. Music—an aid to productivity. Appl Ergonomics. 1972;3(4):202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies DR, Lang L, and Shackleton VJ. The effects of music and task difficulty on performance at a visual vigilance task. Br J Psychol. 1973;64(3): 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terry GR. Office Management and Control. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin; 1975:451.

- 7.Engels F. The Condition of the Working Class in England. London: Penguin Books; 1987:182.

- 8.Select Report of the Commissioners on the Employment of Children (Trades & Manufactures). 1843; P.P. vol. XIII: 195–199.

- 9.Hunter D. The Diseases of Occupations (6th ed.). London: Hodder and Stoughton; 1978:963–964,982.

- 10.London Metropolitan Archives. The Great Dock Strike, 1889. Information leaflet No 19.1999. Available at: http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/NR/rdonlyres/C27142E4-DEFC-4161-AE95-F4B45716E7D4/0/LH_LMA_dockstrike.PDF. Accessed May 20, 2005.

- 11.Elbourne RP. “Singing away to the click of the shuttle”: musical life in the handloom weaving communities of Lancashire. Local Historian. 1976;12(1): 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller J. More on workers’ songs. Music and Life. January 1962:6–10. Located at: Charles Parker Archive, Birmingham City Archives, Central Library, Birmingham, United Kingdom. CPA/1/8/5.

- 13.Ward J. Songs of protest and railway industrial songs. Music and Life. January 1975:13–15. Located at: Charles Parker Archive, Birmingham City Archives, Central Library, Birmingham, United Kingdom. CPA/1/8/5.

- 14.Sahnow W. WMA: Twenty One Years. London, United Kingdom: Workers’ Music Association; 1957:4–6.

- 15.Brocken M. The Battle of the Field: the political context of the hagiography of the second British folk revival. Available at: http://www.mustrad.u-net.com/topic.htm. Accessed May 9, 2005.

- 16.Connell J. The Red Flag. In: 48 Songs: Community Singing. London, United Kingdom: Workers’ Music Association; 1960–1963:8. Located at: Charles Parker Archive, Birmingham City Archives, Central Library, Birmingham, United Kingdom. CPA/1/8/5.

- 17.Music Their Holiday: The Story of the W. M. A. Summer School. London, United Kingdom: Workers’ Music Association; 1960–1961:8. Located at: Charles Parker Archive, Birmingham City Archives, Central Library, Birmingham, United Kingdom. CPA/1/8/5.

- 18.Radio in wartime: should it be grave or gay? Radio Times: J British Broadcasting Corporation. 1940; 67(873):3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.For the forces: Wednesday June 26. Radio Times: J British Broadcasting Corporation. 1940;67(873):16. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnard S. On the Radio: Music Radio in Britain. Milton Keynes, United Kingdom: Open University Press; 1989:23.

- 21.For the forces: Sunday June 23. Radio Times: J British Broadcasting Corporation. 1940;67(873):7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Home service: Thursday July 4. Radio Times: J British Broadcasting Corporation. 1940;68(874):24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Home service: Monday June 24. Radio Times: J British Broadcasting Corporation. 1940;67(873):12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds W. A note on “Music While You Work.” In: BBC Yearbook 1945. London, United Kingdom: British Broadcasting Corporation; 1945:60.

- 25.Aston L. The Radio-Ballads 1957–1964 [sleeve notes]. In: MacColl E, Parker C, Seeger P. The Big Hewer: a Radio-Ballad About Britain’s Coal Miners [compact disc]. London: Topic Records; 1966. TSCD 804.

- 26.MacColl E, Parker C, Seeger P. The Big Hewer: a Radio-Ballad About Britain’s Coal Miners [compact disc]. London: Topic Records; 1966. TSCD 804.

- 27.MacColl E. The Big Hewer: a Radio-Ballad about Britain’s Coal Miners [sleeve notes]. In: MacColl E, Parker C, Seeger P. The Big Hewer: a Radio-Ballad about Britain’s Coal Miners [compact disc]. London: Topic Records; 1966. TSCD 804.