Abstract

In exploring the history of involuntary sterilization in California, I connect the approximately 20 000 operations performed on patients in state institutions between 1909 and 1979 to the federally funded procedures carried out at a Los Angeles County hospital in the early 1970s.

Highlighting the confluence of factors that facilitated widespread sterilization abuse in the early 1970s, I trace prosterilization arguments predicated on the protection of public health.

This historical overview raises important questions about the legacy of eugenics in contemporary California and relates the past to recent developments in health care delivery and genetic screening.

THE YEAR WAS 1979 AND THE place was the state capitol in Sacramento, Calif. Assemblyman Art Torres, chairman of the Health Committee, introduced a bill to the legislature to repeal the state’s sterilization law. First passed in the same chambers 70 years earlier and modified several times over the decades, this statute had sanctioned over 20 000 nonconsensual sterilizations on patients in state-run homes and hospitals, or one third of the more than 60 000 such procedures in the United States in the 20th century. In a letter to Governor Edmund G. Brown urging his signature, Torres asserted that the law was “outdated” and that the criteria used to authorize a sterilization order, specifically the clauses referring to a “marked departure from normal mentality” and to the genetic origins of mental disease, had “no meaning in modern medical terminology.”1 Backed by the Department of Developmental Services and the California Association for the Retarded, this bill was unanimously approved in the State Assembly and Senate, in committee and on the floor.2

On the surface, this vignette might seem to encapsulate little more than the purging of an antiquated law, enacted infrequently since the 1950s, from the legislative annals. Torres, however, had learned that California’s sterilization law was still on the books only when several residents of his predominantly Latino Los Angeles district sued the Women’s Hospital at the University of Southern California/Los Angeles County General Hospital (hereafter called County General) for nonconsensual sterilizations in 1975.3 The plaintiffs in this class-action suit, Madrigal v Quilligan, were working-class Mexican-origin women who had been coerced into postpartum tubal ligations minutes or hours after undergoing cesarean deliveries. In contrast to the operations carried out at state institutions beginning in 1909, these procedures were financed by federal agencies that began to disperse funds in conjunction with the family planning initiatives of the War on Poverty, launched by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964.

For the most part, Madrigal v Quilligan has been understood in light of the thousands of unwanted sterilizations reported in the United States from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s. And certainly, the experiences of the Mexican-origin women who suffered at the scalpels of County General physicians mirror those of the African American, Puerto Rican, and Native American women who came forth with comparable stories during the same years. Yet Madrigal v Quilligan should also be analyzed longitudinally, as a concluding link in the history of forced sterilization in modern California. Just as this case highlights the confluence of factors that facilitated sterilization abuse in the early 1970s, it also illuminates the longevity and potency of prosterilization arguments predicated on the protection of the public’s health and resources.

Madrigal v Quilligan demonstrates shifts over the past century in terms of the rationale employed to authorize compulsory sterilizations and the uneven transition from state coercion to patient choice in matters pertaining to procreation and reproductive health. To offer historical insight into these complex patterns and better comprehend the fraught politics of reproductive control, I explore the intersections of race, sex, immigration, sterilization, and health policy by tracing the chronology and context of involuntary sterilization in modern California. I conclude by suggesting some of the implications of this history for contemporary public health programs.

JUSTIFYING STERILIZATION: FROM DEFECTIVE HEREDITY TO OVERPOPULATION

When Indiana passed the country’s first sterilization law in 1907, it was motivated by the eugenic family studies of supposedly defective lineages, such as the Jukes and the Kallikaks, that were very much in vogue at the turn of the century.4 More broadly, such legislation was part of a wave of Progressive Era public health activism that encompassed pure food, vaccination, and occupational safety acts. In 1909, driven by the desire to apply science to social problems, California passed the third sterilization bill in the nation.5 Envisioned by F. W. Hatch, the secretary of the State Commission in Lunacy [sic] (renamed the Department of Institutions in 1921), this legislation granted the medical superintendents of asylums and prisons the authority to “asexualize” a patient or inmate if such action would improve his or her “physical, mental, or moral condition.”6

The law was expanded in 1913 and 1917, when clauses were added to shield physicians against legal retaliation and to foreground a eugenic, rather than penal, rationale for surgery.7 The 1917 amendment, for example, reworded the description of a diagnosis warranting surgery from “hereditary insanity or incurable chronic mania or dementia” to a “mental disease which may have been inherited and is likely to be transmitted to descendants.”8 It also targeted inmates afflicted with “various grades of feeblemindedness” and “perversion or marked departures from normal mentality or from disease of a syphilitic nature.”9 Performed sporadically at the beginning, operations began to climb in the late 1910s, and by 1921, a total of 2248 people—over 80% of all cases nationwide—had been sterilized in California, mostly at the Sonoma and Stockton facilities.10

Home to an extensive eugenics movement that crisscrossed the domains of agriculture, education, medicine, and government, California was propitious terrain for the emergence of a far-reaching sterilization regimen. Eugenic ideas were espoused by influential professionals, such as Stanford University Chancellor David Starr Jordan, the Santa Rosa “plant wizard” Luther Burbank, and the Los Angeles politician Dr John R. Haynes. In 1924, Charles M. Goethe, a Sacramento businessman, collaborated with University of California zoologist Samuel J. Holmes to found the Eugenics Section of the San Francisco–based Commonwealth Club of California.

Several years later, the agriculturalist and philanthropist Ezra S. Gosney, in consultation with the Eugenics Record Office (located in Cold Spring Harbor, NY), underwrote the Human Betterment Foundation to foment sterilization education and legislation. Gosney eventually selected Paul Popenoe, a date palm cultivator and social hygienist, to conduct a detailed study of sterilization. After collecting data and interviewing patients and staff at state homes and hospitals, he and Gosney coauthored Sterilization for Human Betterment: A Summary of Results of 6000 Operations in California, 1909–1929, which touted the immense value of reproductive surgery and rallied sterilization crusaders across the United States and Europe.11 This mission was furthered by the activities of the Eugenics Society of Northern California, the California Division of the American Eugenics Society, and the American Institute of Family Relations. In addition to these organizations, California’s sterilization system was buoyed by the administration and involvement of the Department of Institutions, which managed state homes and hospitals, several of which were run by ardent superintendents who devised novel surgical techniques.

Because of the state’s multi-faceted eugenics movement and the fact that it appreciably outpaced in absolute terms the other 32 states that passed sterilization laws at some point in the 20th century, California stands out when compared with the rest of the country. California carried out more than twice as many sterilizations as either of its nearest rivals, Virginia (approximately 8000) and North Carolina (approximately 7600). Furthermore, in many states, such as New Jersey and Iowa, sterilization laws were declared unconstitutional, judged to be “cruel and unusual punishment” or in violation of equal protection and due process.12 In contrast, California’s statute—although reworked over the years—remained in effect without interruption from initial passage until repeal.

One of the reasons for this longevity was that, from the outset, California defined sterilization not as a punishment but as a prophylactic measure that could simultaneously defend the public health, preserve precious fiscal resources, and mitigate the menace of the “unfit” and “feebleminded.” California’s prescience was acknowledged in 1927, when the most powerful judiciary in the land, the US Supreme Court, ruled affirmatively on the constitutionality of Virginia’s sterilization statute in Buck v Bell, countenancing sterilization on behalf of the collective health of the citizenry.13 Shaped by the legal struggles over states’ rights to vaccinate that had played out in the 19th century, and drawing from Jacobson v Massachusetts (1905), which had ruled that maintaining the public health outweighed individual rights when it came to smallpox immunization, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in his Buck v Bell opinion: “It is better for the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. Three generations of imbeciles are enough [italics added].”14

If utilitarian pursuit of the common good required mandatory vaccination to inoculate against communicable diseases, it also necessitated “immunizing” the hereditarily defective in order to prevent the spread of bad genes. Once seen as integral to health prophylaxis and as a cost-saving recourse, sterilization programs intensified at a clipped pace across the country in the 1930s.15 By 1932, twenty-seven states had laws on the books and procedures nationwide reached over 3900.16 Not only did operations increase markedly during this decade, but some states, such as Georgia and South Carolina, passed legislation for the first time.17

In California, at least into the 1950s, compulsory sterilization was consistently described as a public health strategy that could breed out undesirable defects from the populace and fortify the state as a whole. Convinced of its efficacy, sterilization proponents pushed for implementation of the law beyond the walls of state institutions. For example, in his Los Angeles Times Sunday magazine column “Social Eugenics” (which ran from 1936 to 1941), Fred Hogue claimed that “in this country we have wiped out the mosquito carriers of yellow fever and are in a fair way to extinguish the malaria carriers: but the human breeders of the hereditary physical and mental unfit are only in exceptional cases placed under restraint.”18 To rectify this situation, Hogue recommended broader intervention and argued that eugenic practices, above all sterilization, were essential to “the protection of the public health” and “the health security of the citizens of every State.”19 second edition of their popular textbook Applied Eugenics, Popenoe and colleague Roswell H. Johnson underscored that “if persons whose offspring will be dysgenic are so lacking in intelligence, in foresight, or in self-control that they do not control themselves, the state must control them. Sterilization is the answer.”20

Rooted in this logic and shored up by Buck v Bell, sterilizations rose dramatically in California in the 1930s, peaking at 848 in 1939 and 818 in 1941. By 1942, over 15 000 operations had been performed in the state, most since 1925.21 Even when per capita comparisons are made with states with much smaller populations, California’s rates were always clustered at the top. Not until the 1940s, when California claimed about 60% of all operations nationwide, did a few states, such as Delaware, North Carolina, and Virginia, begin to consistently overtake California in either per capita or annual terms.22

Although, for a variety of reasons, it will be next to impossible ever to determine with any accuracy the total number of sterilizations, not to mention the statistical and demographic trends, some patterns are discernible.23 In his exhaustive survey of state hospitals and homes in the late 1920s, and in a follow-up study about a decade later, Popenoe found that the foreign-born were disproportionately affected, constituting 39% of men and 31% of women sterilized.24 Of these, immigrants from Scandinavia, Britain, Italy, Russia, Poland, and Germany were most represented.25 These records also reveal that African Americans and Mexicans were operated on at rates that exceeded their population. Although in the 1920 census they made up about 4% of the state population, Mexican men and Mexican women, respectively, comprised 7% and 8% of those sterilized. Without the forced repatriations of hundreds of Mexicans from state facilities, orchestrated by the Deportation Office of the Department of Institutions, it very likely that this figure would have been higher.26 More striking, at the Norwalk State Hospital, in southern California, where a total of 380 Mexicans constituted 7.8% of admissions from 1921 to 1930, they were sterilized at rates of 11% for females and 13% for males.27

In addition, whereas African Americans constituted just over 1% of California’s population, they accounted for 4% of total sterilizations.28 While the age of those sterilized varied according to sex, institution, and marital status, the bulk were in the 20-to 40-year age bracket, with a mean age of commitment of about 30 years for men and 28 years for women; sterilization typically occurred less than 12 months after admission.29 Furthermore, unnamed patient records from the 1920s document hundreds of individuals in their late teens and early 20s sterilized for dementia praecox (schizophrenia), epilepsy, manic depression, psychosis, feeblemindedness, or mental deficiency. A notable percentage of these young patients were typed as masturbators or incest perpetrators if male and as promiscuous—even nymphomaniacal—or having borne a child out of wedlock if female.30

As scholars have shown, California’s sterilization program was propelled by deep-seated preoccupations about gender norms and female sexuality.31 Especially after the procedure of salpingectomy became faster and less medically risky in the 1920s, the sterilization of women and young girls categorized as immoral, loose, or unfit for motherhood intensified. This trend is captured by the changing ratio between sterilizations carried out at institutions for the mentally ill and those performed at institutions for the feebleminded. Initially, most operations took place at the former, affecting more men than women; by the late 1930s, this pattern reversed itself and the gender ratio approached parity. Additionally, Popenoe categorized most sterilized women as homemakers and most men as manual laborers, not as white-collar professionals, indicating that most of those sterilized were either working class or lower middle class.32

The final substantial year for California’s sterilization program was 1951, with 255 operations performed. The following year, the number dropped considerably to 51, undoubtedly because of a revision to the statute inserting administrative requirements for physicians and safeguards for patients.33 This amendment, and another 1953 bill, deleted any references to syphilis (long since understood as microbial, not genetic, in etiology) and sexual perversion; instituted more demanding processes of notice, hearing, and appeal; and removed the terms “idiots” and “fools” from the law.34 By turning what had been a mere formality into a more taxing ordeal, these modifications deterred many physicians from requesting sterilization orders.35 Nevertheless, surgeries continued sporadically at every state institution into the 1970s.

In part, this legal modification reflected a shift in the criteria employed to sanction reproductive surgery, as an emphasis on parenting skills and welfare dependency began to supplant hereditary fitness and putative innate mental capacity as the determinants of an individual’s social and biological drain on society. By this time, many eugenicists had conceded that earlier attempts to stamp out hereditary traits defined as recessive or latent, including alcoholism, immorality, and the catchall “feeblemindedness,” had been proven futile by the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium principle, which demonstrated that the overwhelming tendency of gene frequencies and ratios was to remain constant from one generation to the next. Thus, targeted interventions, such as sterilization, could not breed out defects; even if viable, they would show results only after thousands of years of regulated procreation.36 More and more, eugenicists traded in “unit characters” for polygenic inheritance and genetic predispositions. Accompanying this realignment was a heightened interest in the manipulation and management of human heredity through population control, which postwar eugenicists and their allies pursued through groups such as the Population Council, Population Reference Bureau, and Planned Parenthood.

On the basis of a revamped rationale of bad parenthood and population burden, sterilizations increased in the 1950s and 1960s in southern states such as North Carolina and Virginia.37 Concurrently, sterilization often regained a punitive edge and, preponderantly aimed at African American and poor women, began to be wielded by state courts and legislatures as a punishment for bearing illegitimate children or as extortion to ensure ongoing receipt of family assistance.38 By the 1960s, the protracted history of state sterilization programs in the United States, and the consolidation of a rationale for reproductive surgery that was linked to fears of overpopulation, welfare dependency, and illegitimacy, set the stage for a new era of sterilization abuse. In California, which never explicitly endorsed a punitive model, the state program was fairly quiescent by the mid-1950s. However, when federal backing for reproductive surgery began to be distributed in the late 1960s, the eugenic refrains of previous decades resurfaced. The reproductive tendencies of working-class Mexican-origin women were reviled in accordance with long-standing ideas of public health protection, along with more recent claims that these fecund female immigrants were worsening an already severe overpopulation problem.

MADRIGAL V QUILLIGAN

A series of overlapping factors created the milieu for widespread sterilization abuse in the United States from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s. This period saw the confluence of the gains of mainstream feminism with regard to reproductive rights, an unprecedented federal commitment to family planning and community health, and the popularity of the platform of zero population growth, which was endorsed by immigration restrictionists and environmentalists and put into practice on the operating table by some zealous physicians.

On the one hand, there was increased availability of and access to birth control, including abortion. For example, by 1970, North Carolina, Virginia, Oregon, and Georgia had passed voluntary sterilization laws and Washington, DC and New York had legalized abortion.39 Quite simply, more women were using birth control, especially after the intrauterine device (IUD) and the birth control pill came on the market in the 1960s. Voluntary sterilization rates rose in tandem so that, in 1973, the same year abortion was decriminalized by the US Supreme Court in Roe v Wade, sterilization was the most used method of birth control by Americans in the 30- to 44-year age bracket.40 On the other hand, in 1969 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists dropped its age-parity stipulation, which required that a woman’s age, multiplied by the number of her children, equal 120 in order to qualify for voluntary sterilization. The following year, it retracted the proviso that a woman needed to consult 2 doctors and a psychiatrist before surgery.41

Federal funding for birth control and family planning also rose markedly in the late 1960s, most decisively with the passage of the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act in 1970 and the creation of the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). Among its many duties related to coordinating the War on Poverty’s programs, the OEO was commissioned with introducing contraception and related education programs to millions of underserved women. In 1965, about 450 000 women had access to family planning projects; by 1975, this number had jumped to 3.8 million.42 In 1971, after some initial hesitation, the OEO incorporated sterilization into its medical armamentarium. At the same time, Medicaid was permitted to reimburse up to 90% for an operation.43 Factoring in the sterilizations backed by Medicaid and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) before the OEO’s decision, between the late 1960s and 1974, when federal guidelines were formalized, approximately 100 000 sterilizations were carried out annually.44

In theory, the advent of family planning resources and reproductive health clinics could provide millions of American women and men with heretofore scarce or nonexistent medical services. However, the increasing access to contraception overwhelmingly benefited middle-class White women.45 Against the injunction to define themselves primarily as breeders, mainstream feminists framed their struggle for reproductive and sexual autonomy in terms of the right to obtain birth control, above all abortion, elevating its federal legalization to their utmost goal.46 While many minority and working-class women also clamored for greater reproductive control, they often found themselves combating the reverse equation, namely, that they were destructive overbreeders whose procreative tendencies needed to be managed.47 Given that the family planning model was underpinned by the principles of population control and the ideal of 2 to 3 children per couple, a substantial influx of resources into birth control services and the absence of standardized consent protocols made the environment ripe for coercion.

One of the most well-known cases of sterilization abuse was that of the Relf sisters, aged 12 and 14, who were sterilized without consent in 1973 in Alabama in OEO-financed operations overseen by the Montgomery Community Action Committee. When the Southern Poverty Law Center sued on their behalf, it was revealed that their mother, who could not read, had unwittingly approved the procedures. Believing she was authorizing birth control for her daughters in the form of Depo-Provera injections, she signed an “X” on what was actually a sterilization release.48

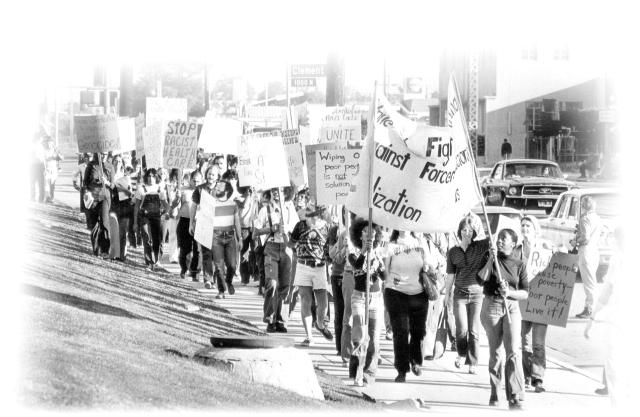

Figure 2.

Protest in Los Angeles against coerced sterilizations at the Women’s Hospital of the University of Southern California–Los Angeles County General Hospital, 1974. With permission of the Los Angeles Times.

By the time the Relfs held a press conference in 1973, African American and Native American women from across the South and Southwest were coming forth with parallel allegations.49 When Relf v Weinberger was heard in federal district court, Judge Gerhard Gesell concluded that “an indefinite number of poor people have been improperly coerced into accepting a sterilization operation under the threat that variously supported welfare benefits would be withdrawn unless they submitted,” and added that “the dividing line between family planning and eugenics is murky.”50 Gesell estimated that over the past several years, 100 000 to 150 000 low-income women had been sterilized under federal programs.51

Unlike many of the African American women who filed suit in the South, the plaintiffs in Madrigal v Quilligan were neither welfare recipients nor on trial for illegitimacy. Instead, they were working-class migrant women sterilized in a county hospital where obstetric residents were pressured to meet a quota of tubal ligations and where the physicians at the top of the chain of command were partisan to racially slanted ideas about population control. In 1973, appalled by the unethical behavior he witnessed during his residency at County General, Dr Bernard Rosenfeld coauthored a report on sterilization abuse across the nation. At County General, he recorded the following dramatic increases during the period from July 1968 to July 1970: a 742% increase in elective hysterectomies, a 470% increase in elective tubal ligations, and a 151% increase in postdelivery tubal ligations.52 Rosenfeld described a situation in which there was “little evidence of informed consent by the patient,” where doctors were “selling” sterilizations “in a manner not unlike many other deceptive marketing practices.”53 According to Rosenfeld, County General obstetricians instructed residents to strong-arm vulnerable patients into accepting tubal ligations, often packaging the operation as a chance to gain needed surgical training.54

Cognizant of what was transpiring at County General, Mexican American women in Los Angeles began to organize and investigate, eventually locating 140 women who claimed they had been forcibly sterilized in medically unnecessary surgeries.55 As with Puerto Ricans on the East Coast, the sterilization cases galvanized Mexican American feminists, who distinguished themselves both from White feminists, whose quest for abortion rights often made them oblivious to reproductive abuse, and Mexican American nationalists, who frequently cast birth control as either superfluous to race and class or, more stridently, as treason against the perpetuation of the ethnic family and nation.56 Mexican American feminists mobilized demonstrations against County General and formed the Committee to Stop Forced Sterilization, which linked sterilization to federal antipoverty programs, the greed of big international corporations, and the oppression of poor people worldwide.57

Madrigal v Quilligan, which ultimately pitted 10 sterilized women against obstetricians at County General, began in May 1978. The plaintiffs charged that their civil and constitutional rights to bear children had been violated, and that between 1971 and 1974 they had been victims of unwanted operations: coerced into signing consent forms hours or minutes before or after labor, not told that the procedure was irreversible, or simply sterilized without giving any consent.58 Antonia Hernández and Charles Nabarette of the Los Angeles Center for Law and Justice represented the plaintiffs, all of whom were low-income monolingual Spanish speakers who had emigrated to California in their teens from rural areas in Mexico in search of economic opportunity or to join relatives.

Although they varied by age, occupation, and number of children, their stories were strikingly similar. All of them had been approached about sterilization after having been in labor for several hours and had endured difficult childbirths, eventually performed by cesarean delivery.59 Their lawyers averred “these women were in such a state of mind that any consent which they may have signed was not informed,” and that in 3 cases, no consent was obtained.60 Rebecca Figueroa was falsely given the impression that she was submitting to a reversible procedure. Elena Orozco was told that her hernia would be repaired only if she agreed to be sterilized, which she refused repeatedly, “until almost the very last minute when she was taken to be delivered.”61 At no point after being admitted to County General in 1973 did Guadalupe Acosta sign a consent form.62 Dolores Madrigal did so after a medical assistant told her that her husband had already offered his signature, something that was patently untrue. Their accusations were supported by the affidavits of 7 additional women, one of whom stated that a County General doctor told her after her cesarean delivery that “I had too many children” and that “having future children would be dangerous for me.”63

Despite corroborating testimony about sterilization abuse at County General, the judge decided for the defendants, whom he determined had acted in good faith and intended no harm. Only one key witness, Karen Benker, spoke out against the doctors. Then a medical student and technician, Benker related an entrenched system of forced sterilization based on stereotypes of Mexicans as hyperbreeders and Mexican women as welfare mothers in waiting. She recalled conversations in which Dr Edward James Quilligan, the lead defendant and head of Obstetrics and Gynecology at County General since 1969, stated, “poor minority women in L. A. County were having too many babies; that it was a strain on society; and that it was good that they be sterilized.”64 She also testified that he boasted about a federal grant for over $2 billion dollars he intended to use to show, in his words, “how low we can cut the birth rate of the Negro and Mexican populations in Los Angeles County.”65 According to Benker, sterilizations were particularly pushed on women with 2 or more children who underwent cesarean deliveries. Facing the animosity of the judge, Benker’s voice was marginalized and drowned out against the other, mostly male, experts heard on the stand.

Hernández and Nabarette waived the option of a jury trial, placing adjudication in the sole hands of Judge Jesse Curtis. Although Curtis acknowledged that the women had “suffered severe emotional and physical stress because of these operations,” he refused to blame County General physicians for what he called “a breakdown in communication between the patients and the doctors.”66 He found “no evidence of concerted or conspiratorial action” and, furthermore, was persuaded by the defendants’ contentions that they “would not perform the operation unless they were certain in their own mind that the patient understood the nature of the operation and was requesting the procedure.” 67 Although Curtis did not sanction neo-Malthusian theories, he stated that it was not objectionable for an obstetrician to think that a tubal ligation could improve a perceived overpopulation problem, as long as the physician did not try to “overpower the will of his patients.”68 Curtis depicted the suit as a “clash of cultures,” and, relying on a simplistic interpretation of Mexican culture, suggested that if the plaintiffs had not been naturally inclined toward such large families, their postpartum sterilizations would have never congealed into a legal case.

Even though the plaintiffs lost, Madrigal v Quilligan did have major consequences for the formulation of sterilization stipulations—most importantly, securing a clause that consent forms be bilingual.69 Now under many watchful eyes, County General began to comply with federal guidelines, including a 72-hour waiting period between consent and operation, a near moratorium on sterilization of persons younger than 21 years of age, and a signed statement of consent preceded by a clear explanation that welfare benefits would not be terminated if the patient declined the procedure. These guidelines officially took effect in 1974, although persistent violations and inconsistencies in hospitals across the country spurred over 50 organizations to meet in Washington, DC in 1977 to push for stricter enforcement and oversight by HEW.70

Madrigal v Quilligan was one aspect of the federally funded sterilization abuse that unfolded in the United States between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s. Nonetheless, the language used to disparage these women, indeed to deprive them of their human rights, had a much older origin. As early as the 1920s, California eugenicists such as Goethe, Jordan, and Holmes asseverated that Mexicans were irresponsible breeders who flooded over the border in “hordes” and undeservingly sapped fiscal resources. In 1935, for example, Goethe wrote to Harry H. Laughlin, superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office, “It is this high birthrate that makes Mexican peon immigration such a menace. Peons multiply like rabbits.”71

In editorials, pamphlets, and personal correspondence, prominent eugenicists foregrounded the “Mexican problem” as a danger to the state’s public and fiscal health. Moreover, during the Great Depression, Popenoe began to reconceptualize this as a “problem” not just of defective heredity but misguided parenthood. In a 1934 study tracking 504 households that had received public aid, many of which were “producing children steadily at public expense,” Popenoe and a colleague reported that of all the groups, Mexicans had the largest family size, a mean of 5.20 living children.72 These kinds of parents, however, rarely produced children of “superior quality”; much more common were “eugenically inferior” offspring. Popenoe recommended that every new charity case be given contraceptive instructions and materials, and that, “beyond this, sterilization at public expense [should] be provided for selected patients who desire it.”73

The Madrigal v Quilligan sterilizations were not directed by the Department of Institutions, but they cannot be extracted from the chronology of involuntary sterilization in California, particularly since they occurred in Los Angeles, which, after the dissolution of the Eugenics Section of the Commonwealth Club of California in 1935, overtook San Francisco as the Pacific West’s eugenic epicenter. Los Angeles was home to some of the country’s most dynamic eugenic organizations, which included physicians affiliated with the University of Southern California hospital system. Whether in operations in state institutions or federally funded county hospitals, most of those sterilized were the foreign born, the working class, and young women deemed “unfit” to procreate or parent.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CALIFORNIA’S PUBLIC HEALTH PROGRAMS

The legacy of involuntary sterilization lingers in California. It is no coincidence, for instance, that the Golden State was home to Proposition 187, which was passed by a majority of votes in 1994 and strove to drastically restrict health, educational, and social services to “illegal aliens.” Its intent and rhetoric strongly resembled that iterated by California eugenicists and the Department of the Institutions in the early 20th century in terms of who deserved access to health services during pregnancy (in this permutation, denial rather than the imposition of reproductive control), who was allowed to reproduce on American soil, and who should be deported. Discursively unoriginal, it targeted Mexicans, who were portrayed as infectious hyperbreeders, alien invaders, and vampires threatening to bankrupt the state. Because of its negation of basic rights to an entire class of individuals, Proposition 187 was swiftly contested in the courts and ruled unconstitutional in 1998.74

If Proposition 187 demonstrates the perduring eugenic and fiscal logic of public health prophylaxis, then California’s innovative prenatal testing program reveals the difficult ethical questions raised by contemporary instances of public health genetics. In 1986, California was first state to pass a law requiring that all pregnant mothers be offered MSAFP (maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein) screening to assess the likelihood of Down syndrome, spina bifida, and neural tube defects. Rather than making such testing compulsory, this law mandates that genetic counselors inform patients of the availability of MSAFP. As studies show, however, given societal pressure to use extant medical technologies in order to do the “best” for one’s children, many women accede to prenatal testing even if, for linguistic or cultural reasons, the implications of testing or positive diagnosis are unclear.75

Focusing on California, 2 medical anthropologists have described scenarios in which Mexican-origin women are, usually inadvertently, receiving incomplete or distorted information about genetic screening and its meanings.76 This situation is exacerbated by a dearth of minority and bilingual genetic counselors trained and prepared to translate complex scientific and technical information to diverse patient populations.77 However, it is also related to genetic professionals’ desire to distance themselves from the coercive practices associated with eugenics, a psychological technique defined as “non-directiveness.” 78 Even if motivated by noble intentions, attaining such neutrality is not only unrealizable, given that social values are embedded in medical institutions and decisions, but often frustrates patients, especially those from newly arrived immigrant groups who expect expert advice from genetic practitioners.79

With California at the forefront, the demographics of the United States are changing, and it is likely that within a century Whites will no longer constitute the nation’s racial/ethnic majority. At the same time, genetic and reproductive technologies are proliferating and, although not necessarily offering therapy or cure, will generate information about the probabilities of genetic diseases that, in turn, will need to be communicated in a culturally sensitive manner. This is a great challenge for the 21st century; as a crucial component of tomorrow’s public and reproductive health, it can be ethically enhanced by awareness of the ways in which history weighs on contemporary biomedicine and society.

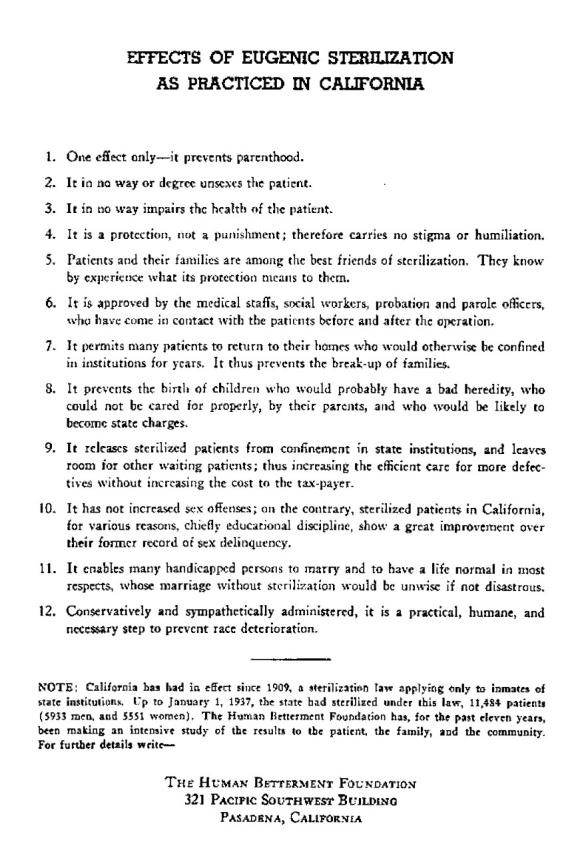

Figure 1.

“Effects of Eugenic Sterilization as Practiced in California,” leaflet disseminated by the Human Betterment Foundation, Pasadena, Calif, from the late 1920s to the early 1940s.

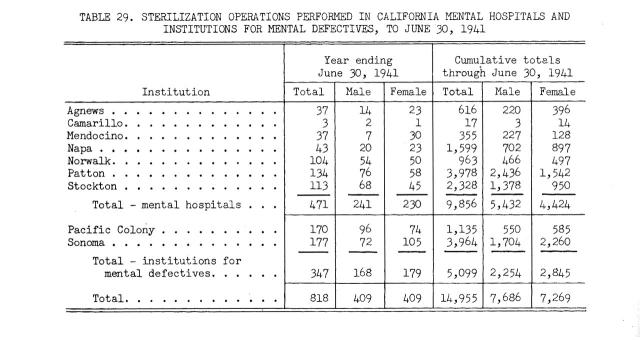

Table 1.

“Sterilization Operations Performed in California Mental Hospitals and Institutions for Mental Defectives, to June 30, 1941,” in the Statistical Report of the Department of Institutions of the State of California (Sacramento: California State Printing Office, 1941).

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at the Spirit of 1848 History session at the 131st Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; November 16–19, 2003; San Francisco, Calif; it also draws from my forthcoming book Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (University of California Press).

I am grateful to Anne-Emanuelle Birn, Natalia Molina, Howard Markel, Gabriela Arredondo, Elizabeth Fee, and 3 anonymous reviewers for their incisive comments and suggestions.

Peer Reviewed

Endnotes

- 1.Art Torres to Edmund G. Brown, Jr., September 7, 1979, Legislative History, Assembly Bill 1204, Microfilm 3:3 (57), California State Archives (CSA).

- 2.“Enrolled Bill Report,” August 31, 1979, Legislative History, Assembly Bill 1204, Microfilm 3:3 (57), CSA; California’s Compulsory Sterilization Policies, 1909–1979, Lisa M. Matocq, ed. (Sacramento, Calif: Senate Publications; December 2003).

- 3.Author’s interview with Art Torres, November 17, 2003, San Francisco, Calif.

- 4.These studies often focused on poor rural White families. See Nicole Hahn Rafter, White Trash: The Eugenic Family Studies, 1877–1919 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988).

- 5.Several weeks before California, the state of Washington passed the second sterilization law in the country. See Harry H. Laughlin, Eugenical Sterilization in the United States (Chicago: Psychopathic Laboratory of the Municipal Court, 1922).

- 6.Cited in Laughlin, Eugenical Sterilization, 17; on Hatch, see Joel Braslow, Mental Ills and Bodily Cures: Psychiatric Treatment in the First Half of the Twentieth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

- 7.See “Sterilization in California Institutions,” Sixth Biennial Report of the Department of Institutions for the Year Ending June 30, 1932 (Sacramento: California State Printing Office [CSPO], 1932), 146–147.

- 8.Laughlin, Eugenical Sterilization, 18–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Ibid, 19; also see F. O. Butler, “Sterilization Procedure and Its Success in California Institutions,” Third Biennial Report of the Department of Institutions of the State of California, Two Years Ending June 30, 1926 (Sacramento: CSPO, 1926), 92–97. The “sexual perversion” aspect of the law was amended and clarified with a 1923 statute that applied to those “convicted of carnal abuse of a female under the age of ten years.”

- 10.Braslow, Mental Ills, 56.

- 11.Ezra S. Gosney and Paul Popenoe, Sterilization for Human Betterment: A Summary of Results of 6,000 Operations in California, 1909–1929 (New York: MacMillan, 1929). This was followed 9 years later by Twenty-Eight Years of Sterilization in California (Pasadena, 1938).

- 12.Philip R. Reilly, The Surgical Solution: A History of Involuntary Sterilization in the United States (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), chap. 4. Many of these rulings were delivered in the 1910s and prompted state legislatures to reword and resubmit successful sterilization statutes.

- 13.See Paul A. Lombardo, “Three Generations, No Imbeciles: New Light on Buck v. Bell,” New York University Law Review 60 (1985): 30–62; on sterilization in Virginia, also see Gregory Michael Dorr, “Segregation’s Science: The American Eugenics Movement and Virginia, 1900–1980,” PhD Dissertation, University of Virginia, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quoted in Stephen J. Gould, “Carrie Buck’s Daughter,” Constitutional Commentary 2 (2) (1985): 333; on Buck v. Bell, also see Paul A. Lombardo, “Involuntary Sterilization in Virginia: From Buck v. Bell to Poe v. Lynchburg,” Developments in Mental Health Law 3 (3) (1983): 13–21; Lombardo, “Medicine, Eugenics, and the Supreme Court: From Coercive Sterilization to Reproductive Freedom,” The Journal of Contemporary Health and Law Policy 13 (1996): 1–25; also see Lawrence O. Gostin, Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 15.See Molly Ladd-Taylor, “Saving Babies and Sterilizing Mothers: Eugenics and Welfare Politics in the Interwar United States,” Social Politics 4 (1997): 136–153. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reilly, Surgical Solution, 97–101.

- 17.See Edward J. Larson, Sex, Race, and Science: Eugenics in the Deep South (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995). [PubMed]

- 18.Fred Hogue, “Social Eugenics,” Los Angeles Times, July 5, 1936, 29.

- 19.Fred Hogue, “Social Eugenics,” Los Angeles Times Sunday Magazine, March 9, 1941, 27.

- 20.Paul Popenoe and Roswell Hill Johnson, Applied Eugenics, 2nd ed. (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1933), 160–161.

- 21.Statistical Report of the Department of Institutions of the State of California, Year Ending June 30, 1942 (Sacramento: CSPO, 1943), 98; California’s Compulsory Sterilization Policies; Statistical Report of the Department of Institutions of the State of California, Year Ending June 30, 1935 (Sacramento: CSPO, 1936).

- 22.Figures derived from “US Maps Showing the States Having Sterilization Laws in 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940,” Publication No. 5 (Princeton: Birthright, Inc., nd) in California’s Compulsory Sterilization Policies; Clarence J. Gamble, “Preventive Sterilization in 1948,” Journal of the American Medical Association 141 (11) (1949): 773; Gamble, “Sterilization of the Mentally Deficient Under State Laws,” American Journal of Mental Deficiency 51 (2) (1946): 164–169. Delaware was the only state that outpaced California in per capita terms in the 1930s, with a rate ranging between about 80 and 100 sterilizations per 100 000 individuals.15391482 [Google Scholar]

- 23.There are 4 key reasons for the immense difficulty of accurately calculating sterilization statistics and demographic trends: (1) incomplete archival access, including issues related to patient confidentiality; (2) insufficient clarity regarding the question of whether or not the official statistics include numerous “sent for sterilization only” cases, usually involving young women, not formally committed to state institutions but interned for the sole purpose of reproductive surgery; (3) exclusion in the official statistics of sterilizations in state prisons, 600 of which had been performed in San Quentin alone by 1941; (4) formidable numbers of “voluntary” sterilizations, primarily of women, who, at their own behest or that of relatives or a physician, procured the operation in a private setting. Undoubtedly, some women sought out sterilization as a form of permanent birth control, but the fact that obstetricians affiliated with California eugenics organizations carried out some of these operations raises questions about the extent to which they were voluntary, and, indeed, how to define voluntary or elective at this point in time.

- 24.See Gosney and Popenoe, Twenty-Eight Years of Sterilization in California.

- 25.“Nationality,” Box 28, Folder 8, Papers of Ezra S. Gosney and the Human Betterment Foundation (ESGHBF), Institute Archives (IA), California Institute of Technology (CIT).

- 26.Ibid. Percentages based on 1920 census figures. See “Table E-7. White Population of Mexican Origin, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States: 1910 to 1930,” available at www.census.gov/documents/population, accessed May 10, 2004. California’s total population was 3 264 711, of which Mexicans constituted 121 176.

- 27.“Norwalk Sterilizations,” place of birth worksheet for females, Box 30, Folder 12; “Norwalk Sterilizations,” place of birth worksheet for males, Box 30, Folder 13, ESGHBF, CIT, IA. Numbers and percentages derived from the Biennial Reports of the Department of Institutions from 1922 to 1930 (Sacramento: CSPO).

- 28.Excerpt of “Nationality,” Box 28, Folder 8, ESGHBF, CIT, IA.

- 29.See rough draft of “Twenty-Eight Years of Human Sterilization,” Box 28, Folder 8, ESGHBF, IA, CIT.

- 30.See unnamed patient records in Boxes 39–43, ESGHBF, IA, CIT. Also see Mike Anton, “Forced Sterilization Once Seen as a Path to a Better World,” Los Angeles Times, July 16, 2003, A1.14971391

- 31.For an excellent analysis of gender and sterilization in California, especially at the Sonoma facility, see Wendy Kline, Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics From the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

- 32.See Alexandra Minna Stern, “The Darker Side of the Golden State: Eugenic Sterilization in California,” in California’s Compulsory Sterilization Policies.

- 33.“Background Paper” and “Sterilization Operations in California State Hospitals, April 26, 1909 through June 30, 1960,” in California’s Compulsory Sterilization Policies.

- 34.See Legislative History, Senate Bill 750, Microfilm 3:2(4); “Legislative Memorandum,” April 4, 1953, Legislative History, Assembly Bill 2683, Microfilm Reel 3:2 (10); Frank F. Tallman to Honorable Earl Warren, March 31, 1953, Legislative History, Assembly Bill 2683, Microfilm Reel 3:2(10), CSA.

- 35.See “Background Paper,” in California’s Compulsory Sterilization Policies.

- 36.See Elof Axel Carlson, The Unfit: A History of a Bad Idea (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2001); Diane B. Paul, Controlling Human Heredity: 1865 to the Present (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1995).

- 37.See Johanna Schoen, Choice and Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

- 38.See Julius Paul, “The Return of Punitive Sterilization Proposals: Current Attacks on Illegitimacy and the AFDC Program,” Law & Society Review 3 (1) (1968): 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- 39.See Schoen, Choice and Coercion, chap. 2 and 3; Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867–1973 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

- 40.See Elena R. Gutiérrez, “Policing ‘Pregnant Pilgrims’: Situating the Sterilization Abuse of Mexican-Origin Women in Los Angeles County,” in Women, Health, and Nation: Canada and the United States since 1945, ed. Georgina Feldberg, Molly Ladd-Taylor, Alison Li, and Kathryn McPherson (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 379–403 (citation from p. 381).

- 41.See Thomas M. Shapiro, Population Control Politics: Women, Sterilization, and Reproductive Choice (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1985), 87.

- 42.Ibid, 113.

- 43.Gutiérrez, “Policing ‘Pregnant Pilgrims,’ ” 381.

- 44.Shapiro, Population Control Politics, 115.

- 45.See Linda Gordon, Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right: Birth Control in America, 2nd ed. (New York: Penguin Books, 1990).

- 46.On abortion and mainstream feminism, see Ruth Rosen, The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America (New York: Viking, 2000).

- 47.See Gordon, Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right.

- 48.See Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race, & Class (New York: Vintage Books, 1981), chap. 12; Jack Slater, “Sterilization: Newest Threat to the Poor,” Ebony (October 1973): 150–156. [PubMed]

- 49.Ibid; Shapiro, Population Control Politics; Nancy Ordover, American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

- 50.Quoted in Shapiro, Population Control Politics, 5.

- 51.Ibid, 5.

- 52.A Health Research Group Study on Surgical Sterilization: Present Abuses and Proposed Regulations (Washington, DC: Health Research Group; 1973), 1.

- 53.Ibid, 2.

- 54.Ibid, 7.

- 55.See Diane Ainsworth, “Mother No More,” Reader: Los Angeles’ Free Weekly, January 26, 1979, 4.

- 56.See Virginia Espino, “ ‘Women Sterilized as They Give Birth’: Forced Sterilization and the Chicana Resistance in the 1970s,” in Las Obreras: Chicana Politics of Work and Family, ed. Vicki L. Ruiz and Chon Noreiga (Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Publications, 2000), 65–82; also see Vicki L. Ruiz, From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), chap. 5.

- 57.Committee to Stop Forced Sterilization, “Stop Forced Sterilization Now!” (Los Angeles, n.d.), 3.

- 58.Also see Claudia Dreifus, “Sterilizing the Poor,” in Seizing Our Bodies: The Politics of Women’s Health, ed. C. Dreifus (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 105–120; Adelaida R. Del Castillo, “Sterilization: An Overview,” and Carlos G. Vélez-Ibañez, “Se Me Acabó La Canción: An Ethnography of Non-Consenting Sterilizations Among Mexican American Women in Los Angeles,” in Mexican American Women in the United States: Struggles Past and Present, ed. Madgalena Mora and Adelaida R. Del Castillo (Los Angeles: University of California Chicano Studies Research Center Publications, Occasional Paper No. 2, 1980), 65–70, 71–94.

- 59.“Madrigral v. Quilligan,” No. CV 74–2057-JWC, Report’s Transcript of Proceedings, Tuesday, May 30, 1978, SA 230–240, Papers of Carlos G. Vélez-Ibañez (CGVI), Sterilization Archive (SA), Item 5, Chicano Studies Research Library (CSL), University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA).

- 60.Ibid, 12.

- 61.Ibid, 19.

- 62.Ibid, 12.

- 63.Affidavit of DG, SA 110, CGVI, SA, 5, CSL, UCLA.

- 64.“Madrigral v. Quilligan,” No. CV 74–2057-JWC, Report’s Transcript of Proceedings, Tuesday, May 30, 1978, SA 230–240, CGVI, SA, 5, CSL, UCLA, p. 802.

- 65.Ibid, 797.

- 66.Quoted in “Plaintiffs Lose Suit Over 10 Sterilizations,” Los Angeles Times, July 1, 1978, clipping in CGVI, SA, 5, CSL, UCLA; Elena Rebéca Gutiérrez, The Racial Politics of Reproduction: The Social Construction of Mexican-Origin Women’s Fertility, PhD dissertation, University of Michigan, 1999, p. 212.

- 67.Quoted in Gutiérrez, “The Racial Politics of Reproduction,” 213; quoted in Ainsworth, “Mother No More,” 5.

- 68.Ibid, 208.

- 69.See Gutiérrez, “Policing Pregnant Pilgrims,” 393.

- 70.Shapiro, Population Control Politics, 137; Sterilization Abuse: A Task for the Women’s Movement (Chicago Committee to End Sterilization Abuse, January 1977); Daniel W. Sigelman, Sterilization Abuse of the Nation’s Poor Under Medicaid and Other Federal Programs (Washington, DC: Health Research Group, 1981).

- 71.Charles M. Goethe, press release, March 21, 1935, C-4–6, Papers of Harry H. Laughlin (HHL), Special Collections (SC), Truman State University (TSU).

- 72.Paul Popenoe and Ellen Morton Williams, “Fecundity of Families Dependent on Public Charity,” American Journal of Sociology 40 (2) (1934): 214–220, quote from p. 214, Box 1, Folder 6, ESGHBF, IA, CIT. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ibid, 220.

- 74.See Kent A. Ono and John M. Sloop, Shifting Borders: Rhetoric, Immigration, and California’s Proposition 187 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002); Jonathan Xavier Inda, “Biopower, Reproduction, and the Migrant Woman’s Body,” in In Decolonial Voices: Chicana and Chicano Cultural Studies in the 21st Century, ed. Arturo J. Aldama and Naomi Quiñonez (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), 98–112; Dorothy Nelkin and Mark Michaels, “Biological Categories and Border Controls: The Revival of Eugenics in Anti-Immigration Rhetoric,” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 18: (5–6) (1998): 35–63.

- 75.See Nancy Press and Carol H. Browner, “Why Women Say Yes to Prenatal Diagnosis,” Social Science and Medicine 45 (7) (1997): 979–989; Barbara Katz Rothman, The Tentative Pregnancy: Prenatal Diagnosis and the Future of Motherhood (New York: Penguin, 1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carol H. Browner, H. Mabel Preloran, Maria Christina Casado, Harold N. Bass, and Ann P. Walker, “Genetic Counseling Gone Awry: Miscommunication Between Prenatal Genetic Service Providers and Mexican-Origin Clients,” Social Science and Medicine 56. (2003): 1933–1946. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.See Boston Information Solutions, “National Society of Genetic Counselors, Inc. Professional Status Survey 2002,” December 2002, available at http://www.nsgc.org/pdf/PSS_2002_2_22.pdf, accessed July 20, 2004.

- 78.See Jon Weil, “Psychosocial Genetic Counseling in the Post-Nondirective Era: A Point of View,” Journal of Genetic Counseling 12 (3) (2003): 199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.See Ilana Mittman, William R. Crombleholme, James R. Green, and Mitchell S. Golbus, “Reproductive Genetic Counseling to Asian-Pacific and Latin American Immigrants,” Journal of Genetic Counseling 7 (1) (1998): 49–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]