Abstract

The Brazilian National AIDS Program is widely recognized as the leading example of an integrated HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment program in a developing country. We critically analyze the Brazilian experience, distinguishing those elements that are unique to Brazil from the programmatic and policy decisions that can aid the development of similar programs in other low- and middle-income and developing countries.

Among the critical issues that are discussed are human rights and solidarity, the interface of politics and public health, sexuality and culture, the integration of prevention and treatment, the transition from an epidemic rooted among men who have sex with men to one that increasingly affects women, and special prevention and treatment programs for injection drug users.

For those concerned about the HIV/AIDS pandemic, we are living through the best of times and the worse of times. Since the 13th International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa, there has been growing international attention to the scope and nature of the catastrophe, increased political will in a number of countries, and a substantial, albeit insufficient, increase in available resources. At the same time, the epidemic continues to grow, reversing decades of development in a number of African countries and promoting the very economic and social conditions that facilitate its spread to yet another generation of young people.

A consensus formed at the Durban Conference was that a strategic approach to the HIV epidemic must integrate prevention with care, treatment, and mitigation. This was an implicit rejection of the dominant international paradigm that poor and developing countries must focus only on prevention. Because the demand for treatment has become such a contentious topic, advocates, policy-makers, and researchers have focused special attention on Brazil’s successful program for providing universal access to free antiretroviral therapy.1,2

Many national governments are now developing new, strategic AIDS plans that incorporate enhanced care and treatment for those infected with HIV. The challenge to develop such a program in the context of poorly developed health systems is profound, and there is an understandable and urgent need for direction. “Best practice” strategies have been one answer; however, while inspiring, they are often small-scale projects that focus on a single element of a comprehensive plan (treatment, care, prevention) with limited heuristic value for those charged with formulating an integrated national plan.3 There is also a temptation to decontextualize such programs and mechanically transplant them to radically different settings. Yet, the need to learn from others’ experiences so that mistakes can be minimized and scarce resources allocated correctly remains critical.

With this environment in mind, we present a critical analysis of the development of the Brazilian National AIDS Program (NAP), a widely recognized, leading example of the feasibility and effectiveness of an integrated approach to the epidemic in the setting of a middle-income country characterized by significant levels of social inequality. Even though United Nations indices of human development have consistently placed Brazil around 70th place, the impact of the Brazilian response to AIDS has been impressive: incidence rates of HIV are much lower than projected a decade ago, and mortality rates have fallen by 50% and inpatient hospitalization days by 70% to 80% over the past 7 years.4 While implementation of this program required the commitment of significant resources, it is now estimated that by 2001 an investment of US $232 million resulted in a total savings of US $1.1 billion.5

We do not believe that the Brazilian NAP can serve as a “model” that can be uncritically implemented in other countries; in fact, the most basic lesson from the Brazilian experience may well be that there is no homogeneous HIV/AIDS epidemic nor a prepackaged approach to dealing with it. The way in which a nation responds to the social, political, economic, and human stress (and distress) caused by HIV/AIDS will be shaped by that country’s unique history, culture, governmental institutions, and economic resources and the diverse social forces and institutions that get lumped together as “civil society.” However, we believe there is value in looking at Brazil as a case study, briefly examining the unique Brazilian context and then focusing on specific policy decisions that may be helpful to those grappling with their own national realities.

THE BRAZILIAN CONTEXT

As a consequence of the deep inequalities and regional differences that exist in Brazilian society, the spread of HIV infection has been complex, characterized by a number of diverse patterns in different regions of the country.6,7 In spite of regional differences, however, the Brazilian epidemic is currently characterized by 3 major, interrelated, epidemiological trends that are evident in all regions of the country, which are described by Brazilian researchers as (1) heterosexualization, (2) feminization, and (3) pauperization.8,9

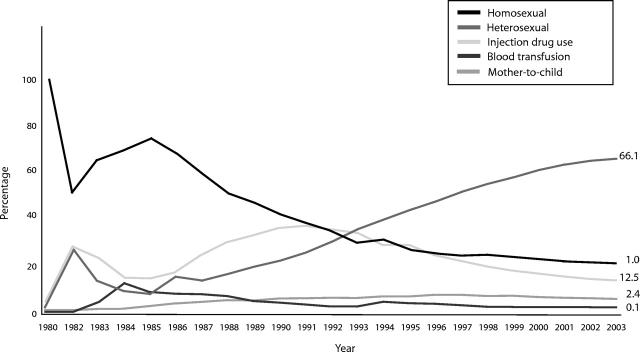

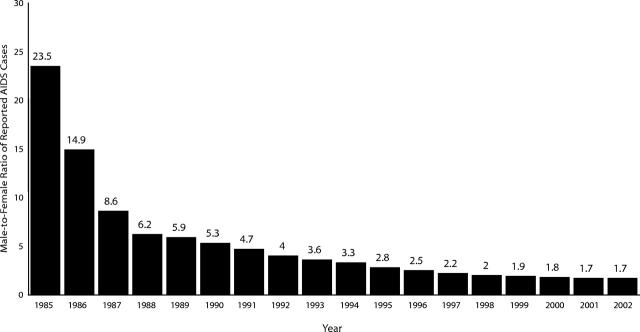

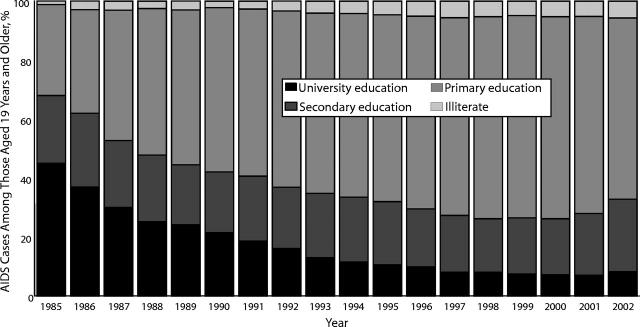

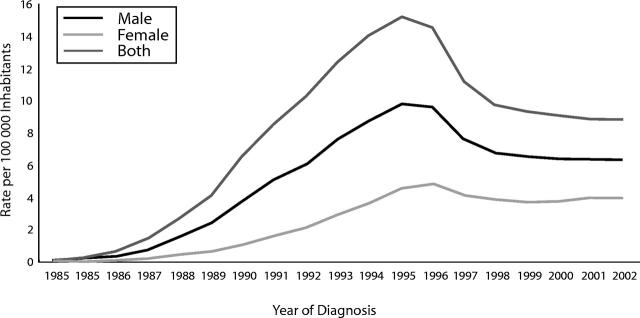

Although the epidemic began in Brazil in the early 1980s primarily through sexual transmission between men, heterosexual transmission has gradually become the major mode of HIV infection (Figure 1 ▶).6 Increased heterosexual transmission has resulted in substantial growth of HIV infection and AIDS cases among women, and the male-to-female ratio of reported cases has shifted from 23.5 to 1 in 1985 to 1.7 to 1 in 2002 (Figure 2 ▶).6 When level of education is used as a proxy for socioeconomic status, the increasing proportion of cases among people with lower education levels indicates a trend of pauperization in the epidemic (Figure 3 ▶).6 These patterns are important in revealing the key challenges that must still be overcome to control the epidemic.

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of AIDS cases by type of transmission and year of diagnosis: Brazil, 1980–2003.

Source. National AIDS Program, Brazilian Ministry of Health.

Note. Notified cases up to December 31, 2003.

FIGURE 2—

Gender ratio (male to female) of notified AIDS cases: Brazil, 1985–2002.

Source. National AIDS Program, Brazilian Ministry of Health.

FIGURE 3—

Percentage of AIDS cases among those aged 19 years and older, by level of education: Brazil, 1985–2002.

Source. National AIDS Program, Brazilian Ministry of Health.

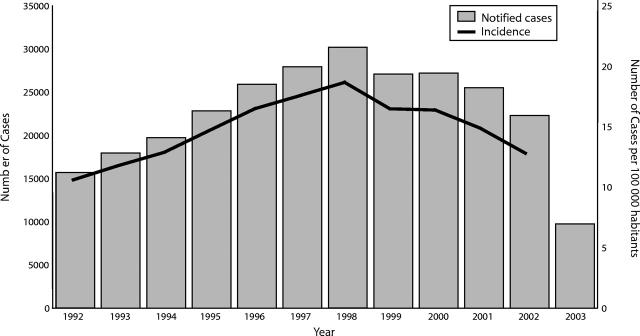

Nonetheless, the effectiveness of Brazil’s response to HIV/AIDS has been demonstrated through Brazil’s historical epidemiological profile, with a clear trend toward the stabilization of the epidemic over time.8 In 1990, the World Bank predicted that within 10 years there would be 1.2 million people infected with HIV in Brazil unless an effective, nationally based intervention was mounted.2 Fourteen years later, this scenario has yet to materialize. On the contrary, an estimated 600 000 people in Brazil are infected with HIV and 362 364 have AIDS.6 Incidence rates of HIV infection are much lower than projected a decade ago (Figure 4 ▶), and mortality rates have fallen by roughly 50% (Figure 5 ▶). Inpatient hospitalization days have been significantly reduced, resulting in lower hospital expenses owing to the investment in treatment access.1,2,4

FIGURE 4—

Number of AIDS cases and incidence rate, by year of diagnosis: Brazil, 1992–2003.

Source. National AIDS Program, Brazilian Ministry of Health.

Note. Notified cases up to December 31, 2003.

FIGURE 5—

AIDS mortality rate, by gender: Brazil, 1984–2002.

Source. National AIDS Program, Brazilian Ministry of Health.

Aspects of the Brazilian response to HIV/AIDS have been described and analyzed by a number of the outstanding activists, social scientists, and public health officials who helped shape that response. There is widespread agreement among these analysts that the Brazilian mobilization against HIV must be viewed in the context of the larger social mobilization of Brazilians confronting the military dictatorship and demanding democracy and a return to civilian rule.10–12

Citizenship, Solidarity, and Social Mobilization

Two key concepts that underlay the social mobilization for democracy (and that would, in turn, prove to be central to the Brazilian response to HIV/AIDS) were “citizenship” and “solidarity.” Citizenship defined the relationship between the Brazilian people and the state (through its democratic institutions); solidarity, and respect for human rights, defined the relationship among the people.10,13,14

In asserting their rights as citizens in the new constitution of 1988, Brazilians were demanding that the city, state, and national administrations enter into a dialog with civil society about the future of the country.15–17 This redemocratization movement built political parties, trade unions, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) throughout the country in the 1980s, culminating in a demand for elections for a new and free Congress. Democratic elections were initially held only at the municipal and state levels. The negotiation and promulgation of the new “democratic” constitution, passed in 1988, included the reinstitution of free national elections as of 1990.

One strong player in this national mobilization for democracy was the “sanitary reform movement,” a loose affiliation of health care workers, collective health academics,18 trade unions, Catholic and Christian churches, and new political parties, who demanded a public health system responsive to and controlled by the public and who defended the right to health as a fundamental human right to be guaranteed by the constitution. The sanitary reform movement19,20 was particularly strong in São Paulo state and city, and when opposition parties won the first state elections, members of that movement were appointed to senior positions in the health department. São Paulo was the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic, and the São Paulo State Health Department led the response to the emergence of the first reported cases of AIDS (in 1983). It later became the model for the National Unitary Health System, typically referred to by its acronym in Brazilian Portuguese, SUS (Sistema Único de Saúde).12,21,22

This mobilization process, in which many diverse social movements made up of Brazilian citizens came together in a common struggle for democracy, was the basis for a sense of social solidarity across many traditional societal divisions.10 This should not be idealized or romanticized: Brazil was and is a nation with great disparities of wealth, a long history of social discrimination based on skin color, and oppressive gender relationships, all of which had (and continue to have) a longstanding negative impact on the health of the Brazilian population.23,24 Despite these very real differences in power and prestige, however, social solidarity built up out of common suffering and the struggle for democracy and citizenship became a countervailing force to the stigma surrounding the emergence of HIV.14,24,25

What were the factors that effectively mitigated the worst aspects of the stigma surrounding both HIV and homosexuality? A critical number of gay men and human rights activists, as well as men and women infected or affected by HIV, openly confronted the stigma, demanding that the rights of people living with AIDS be respected by the government and by their fellow citizens. These developments were particularly important in São Paulo, where opposition to the military regime had been deeply rooted and where opposition political parties had come to power as soon as democratic elections had been restored. In 1983, in response to demands from gay activists, the São Paulo State Secretariat of Health founded the first governmental AIDS program in the country. In 1985, an alliance of gay men, human rights activists, and health professionals came together to form GAPA (the AIDS Prevention and Support Group), the first nongovernmental AIDS service organization, which became an important model for similar organizations in cities around the country.25–28 Similarly, in Rio de Janeiro (like São Paulo, an important center for political opposition), researchers, health professionals, and activists came together to form ABIA (the Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association) in 1986, and the Grupo Pela Vidda (the Group for Life), the first self-identified HIV-positive advocacy group in the country, was founded in 1989.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, a vibrant rebirth of civil society29 led to the formation of NGOs (described in Brazil as ONGs/AIDS or AIDS NGOs) in other key cities and states around the country. Working together with progressive state and municipal health departments, they would pressure the federal government to create a national AIDS program. These factors combined to create an early response to HIV that was based on solidarity and inclusion rather than stigma and exclusion, which in turn provided the foundation for the later development of the national response to AIDS, as discussed under the section heading “Culture.”13,24,25

The political crisis of military rule that precipitated the social mobilization of large numbers of Brazilians cannot be artificially recreated in other countries. Yet there may be important lessons for other countries in the Brazilian experience. The issue of political leadership is often put forward as critical to an effective response to HIV. While that may be true in Uganda and certain other frequently cited examples, political leadership is not necessarily synonymous with governmental leadership. The situation in Brazil (and this is true of many other countries) was that leadership emerged from civil society.13 This is not to downplay the critical role of government in confronting HIV; it was the sometimes tense dialog between civil society and the government in Brazil that resulted in an effective national response. One only has to examine the painful situation in South Africa over the past several years to understand the impact of a government that is unresponsive or too slow to answer and collaborate with civil society initiatives.30,31

Big State, Little State

Attempts to take lessons from the Brazilian experience and use them in developing national AIDS programs in sub-Saharan Africa must take into account the relative strength of the Brazilian public health care system. Its strength is not solely a function of Brazil’s economic standing as a middle-income country; South Africa’s per capita gross national product is also considered middle income by international standards. Brazil and South Africa share similarly high levels of economic polarization—both have a GINI Index of 59.32 In Brazil, as in any other country, political decisions as well as economic resources shape the health care system.

The SUS has unquestionably been a qualitative advance in the history of public health in Brazil.21 Its core principles of integrality (prevention and treatment), public accountability, and public funding distinguish it from early versions of governmental health systems and make it a proper vehicle for comprehensive management of HIV. While recognizing the unique aspects of the SUS, it is equally important to recognize that it emerged from a long tradition of advocacy for governmental responsibility for the health of the nation, albeit a tradition frequently marred by inefficiency, waste, and corruption.22

This social pact was challenged by the embrace of the macroeconomic policies of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank as a solution to problems such as inflation and the debt crisis. These policies, often called “the Washington Consensus,” encouraged foreign capital investment in finance and industry and prioritized fighting inflation through currency devaluation and restricted governmental expenditures on social services. Financing for the public health system was slashed, and the privatization of health services grew rapidly. It was in this context that the movement for redemocratization in Brazil made public health and the human right to health central demands on government (see the section “Health Care as a Human Right”).5,33

South Africa and most other sub-Saharan African countries have a much different political history. The progressive colonization of the continent by European powers was formalized in 1885. Colonial governments were primarily charged with maximizing extraction of raw materials and profits for the colonizing country; health care was largely limited to those interventions necessary to control epidemics that might affect Europeans and to do the minimum necessary to maintain a stable work force. This policy resulted in a stunted public health care system centered in large cities with the greatest European populations, and a health system for African workers in the extractive industries that was under the control of mining companies. Colonial governments (with the exception of some coastal West African countries) reserved administrative and professional positions in the health care system for Europeans and limited access to higher education for Africans. Perhaps the most extreme, but not unrepresentative, example was the Belgian Congo, which had a total of 8 university graduates at the time of independence in 1960.

Political decolonization in most of Africa occurred during the period 1960 to 1970 and was often accompanied by the emigration of the European administrators and physicians responsible for the health care system. A number of newly independent countries made attempts to develop primary health care systems in the decade after independence, but such efforts were often handicapped by insufficient funds and human resources. In other countries, the functions of the state apparatus were never reoriented to serve the needs of the citizenry.34–36

Attempts to strengthen public health systems during this period met strong opposition from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Rather than promote public health, structural adjustment programs forced governments to cut spending on health care and institute users’ fees in the public system. To make a reasonable salary, professionals in the public health system often sought work in the private health care system. The weak health systems that now plague efforts to control HIV in sub-Saharan Africa must be seen as the product of both colonial history and the “small government” model promoted by the Washington consensus.33,37

The AIDS epidemic may force African governments to make public health a priority. African heads of state meeting in Abuja, Nigeria, in 2001 pledged to increase spending on health to 15% of their national budgets. Not one has yet achieved that goal. Correspondingly, promises by the United States and its major European allies to eliminate debt repayment and increase development aid to 0.7% of gross national product have not been implemented.38

The lesson that one can reasonably draw from the Brazilian experience is that governments must acknowledge that health care is as much a central responsibility as national defense and that international agencies cannot merely lament weak health care systems but should take steps to change those macroeconomic policies that hamstring governmental efforts to strengthen those systems.

Health Care as a Human Right

Health care is recognized in the Brazilian constitution as a fundamental right of all citizens and a fundamental responsibility of the government. This status as a fundamental right creates an obligation on the part of the government to take all reasonable steps to actualize that right.

The Brazilian constitution created both a moral and a legal basis for the demand for comprehensive treatment for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). However, it must be recognized that, at least until the mid-1990s, the government itself rarely took the initiative to expand services for PLWHA.26 AIDS advocacy groups developed legal aid programs and brought a series of successful class action suits focused on specific programmatic issues (e.g., free viral-resistance testing, an expanded drug formulary) that have operationalized the constitutional right to health. These law suits, in turn, created a public venue where PLWHA can assert their rights as Brazilian citizens and function as protagonists in their own struggle for life.29,39

Many countries recognize health care as a human right, but in relatively few instances have legal strategies been as fruitful as in Brazil. The Treatment Action Campaign and the AIDS Law Project in South Africa have pursued a similar strategy in the South African courts with some success. Within Latin America and the Caribbean, a number of organizations representing PLWHA have demanded antiretroviral treatment in suits filed against their respective governments before the InterAmerican Court of Human Rights. This court has ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, but it has no direct authority to force governments to comply with its orders.40 What seems to distinguish the Brazilian situation from that of many other countries is that the Brazilian government acts in a timely and appropriate manner to implement court rulings.

Health care as a fundamental right has been operationalized in the SUS. The SUS was founded on and developed from 4 key principles: (1) universal access, (2) integral care, (3) social control, and (4) public funding.

Integral care was a core concept of the sanitary reform movement in Brazil before the debate about the need for linking treatment and prevention emerged within the international AIDS movement.41 Integrality recognizes that the governmental responsibility to health is not limited to the basic prevention measures (e.g., vaccines) found in maternal and child health programs. It asserts that prevention must be integrated with care and treatment. The right to health extends to those already ill and in need of treatment, and there is recognition that having people access the health system will improve the whole range of public health initiatives. Integrality also is based on a commitment to the human rights of those afflicted: a prevention-only approach to health violates those rights and the dignity of those in need of care, devalues their lives, and adds to the stigma that may accompany illness.42,43 This lesson was learned during the development of a plan for Hansen’s disease (leprosy) in São Paulo years before the first case of AIDS in Brazil.12

Social control refers to the direct role that civil society plays in setting the priorities for the SUS. Public health councils with elected community representatives exist at all levels of the SUS: municipal, state, and federal.44 Planning is the responsibility of the federal and state levels, while implementation is done through the municipalities. Over 120 000 people serve on these health councils, setting local programmatic and budgetary priorities within the overall national health plan.

Every 4 years, there is a structured debate at the local and state levels about national health planning; the SUS uses input from this debate to present a plan to a national health conference. This system of controle social or “social control” (as it is described by health activists and government officials alike) is still in the process of being constructed and can still be vulnerable to changing political priorities, as was the case during the Collor government in the early 1990s. Nonetheless, this process has been extended steadily over the course of the past decade, and it starkly contrasts with the bureaucratic nature of public health in many other countries.15 Involvement of PLWHA and other sectors of society is still contentious or only given lip service in many countries; however, such involvement existed in the state of São Paulo and in other regions of Brazil from the very beginning of the AIDS epidemic, eventually becoming the model for the NAP and the proactive response to HIV/AIDS within the SUS.

Centralization vs Decentralization

The balance between centralized functions such as planning, standards, and budgeting, and decentralized functions, primarily implementation, is a problem all national health systems confront. In most countries, the ministry of health initiates programs, issuing directives to state or provincial health departments responsible for regional planning. These regional ministries then direct local health departments to implement the programs. Financing, unfortunately, often does not follow the same direction as the directives.

The SUS and, particularly, the NAP have a different dynamic. As discussed in the section “Health Care as a Human Right,” members of the sanitary reform movement were appointed to a number of large municipal and state health departments in the late 1970s and began to reorganize public health along democratic principles. Dialog, responsiveness, and cooperation characterized the relationship between the health department and civil society groups. In 1983, when the first cases of AIDS were reported in São Paulo, the Brazilian government’s response to demands from gay rights groups was rapid and positive, and strong links were forged between the health department and NGOs.13,20 The program that emerged combined prevention, treatment, surveillance, and support for human rights. While treatment and surveillance remained governmental functions, NGOs increasingly took the lead in the prevention of HIV and the promotion of human rights. The São Paulo AIDS program became the model for other states and ultimately helped shape the NAP.13

The Brazilian response to AIDS thus emerged from the bottom up. It has been characterized by an active collaboration between government and NGOs, as well as by mobilization of activist political support and commitment within the machinery of the state itself, particularly on the part of local service providers in the public health system. While the dynamic between centralization and decentralization within the NAP has fluctuated over time, there remains room for local initiatives, and the alliance with NGOs remains strong.

Equally important, through a succession of different presidential administrations, is that the Brazilian AIDS Program has managed to sustain a consistent commitment to strengthening previously marginalized communities, to defending their rights, and to articulating respect for diversity as a key component of official government policy. Organizations representing sex workers; drug users; gay and lesbian, bisexual, and transgender populations; PLWHA; and other groups affected by the epidemic have received significant funding from the government.25 Support has been provided for more than a decade now for legal aid work carried out by NGOs working on behalf of PLWHA.29 Projects have been funded for lesbian organizations, independent of the relatively low epidemiological risk of HIV infection in this population, precisely because strengthening sexual rights has been understood as central to a broader effective response to the epidemic. Even the annual Gay Pride Parade in São Paulo, which has grown in recent years to draw up to 1 million people from all over the country, has received regular financial support from the Brazilian Ministry of Health. In short, the battle against stigma and discrimination has been understood as central to the response to HIV and AIDS, and it has been waged consistently through the development of partnerships between government and civil society.45

The experience in most other countries differs from that of Brazil. Centralization is dominant in most health ministries, and it is not uncommon for regional and municipal departments to be responsible for implementing programs without receiving funding to deliver the services. It is less common for governments to welcome the input and involvement of NGOs, although a nominal NGO presence is required by almost all international funding agencies. Even fewer governments accept their responsibility to promote and defend the human rights of PLWHA; on the contrary, governments often contribute to civil and human rights abuses through criminalization of risk behaviors (sodomy laws, drug laws, prostitution) and punitive policies toward PLWHA in prisons.

Culture

The commitment to human rights and the early emphasis placed on solidarity as central to the response to HIV/AIDS in Brazil, while articulated as a response to the military authoritarian regime and social inequality, also is clearly deeply rooted in a long-standing emphasis on solidarity in Brazilian culture. Principles of solidarity and reciprocity have long been understood as central to the moral economy of the poor in Brazilian society.46 Solidarity among family members and neighbors is a key element of the survival strategies traditionally employed by poor people with little access to services and social welfare benefits in Brazil. These same principles have been extremely important to critical societal institutions, such as the Catholic Church and the Brazilian state apparatus.47,48 This same principle of solidarity has clearly resonated in response to the plight of PLWHA.

Just as moral principles of solidarity in Brazilian culture have been central to the foundation of a national response to HIV and AIDS, sexuality and sexual expression are also an integral part of Brazilian culture and have facilitated the development of an effective response to the epidemic.10,45,49 Certainly there is more than 1 discourse about sexuality in Brazil—some sectors of the religious community may make moral judgments, just as some in the medical professions may reduce sexuality to decontextualized risk behaviors—but there is a capacity for HIV prevention programs to address sexuality more openly than in most other countries.14 It is notable that condom sales and distribution have risen dramatically in the general population, and there are data that suggest that condom use among HIV-positive people has increased as well.50 Openness about sexuality and the diversity of gender and sexual identities have helped to break down the stigma surrounding both homosexuality and HIV.

Nowhere is the importance of sexual culture in Brazil as clear as in the ways in which prevention programs have been able to address sexuality, focusing on condom promotion while also combating stigma and discrimination. The public service announcements sponsored by the NAP have been among the most explicit of any governmental information campaign in the world. Condom use has been promoted relentlessly, female as well as male condoms have been widely distributed by the Brazilian government, and studies of sexual behavior have demonstrated significant increases in the adoption of condom use across population groups (especially among young people).50 Public information campaigns also have focused on the need to combat stigma and support sexual diversity, with 1 recent campaign focusing on the need for parents to accept and support children who are homosexual. These mass media approaches have been accompanied by significant levels of government support for community-based prevention programs among men who have sex with men, sex workers, young people, and other populations perceived to be at elevated risk of HIV infection.

Just as Brazil has confronted the international community around issues of treatment access, it has also resisted international pressure with regard to prevention programs. While the Brazilian NAP has acknowledged that reducing the number of sexual partners can decrease an individual’s risk of infection, it has also recognized that many people, especially women, are not always able to control the multiple relations of their primary partners. The NAP has therefore been firm in putting condom use at the center of its program.51 This position has caused tension with some international agencies, such as USAID, which came close to closing its AIDS prevention activities in Brazil because of the Brazilian refusal to adopt USAID’s “ABC” (Abstinence, Be faithful, Condoms) prevention strategy, a strategy that explicitly prioritizes both abstinence and fidelity over and above an emphasis on promoting condom use.52–54

Culture cannot be reduced to “best practices” and transferred from one social reality to another. In many countries, AIDS prevention efforts have been blocked by societal and governmental leaders claiming that discussion of sexuality is antithetical to traditional culture. This position assumes that culture is static, unresponsive to changing conditions or focused intervention. The Brazilian experience, as well as that of Uganda, Senegal, and a number of other countries, disproves that generalization.55,56

Harm Reduction

Finally, building on many of the same principles discussed earlier, Brazil’s response to injection drug users provides another key example of the important ways in which the government’s approach has differed from the responses of other governments and yet has still achieved positive results. Injection drug use was limited in Brazil prior to the 1980s; however, as international drug control efforts in the highland Andean region intensified over the course of that decade, Brazil’s largely uncontrolled border became an attractive route for drug trafficking. Subsequently, rates of HIV infection linked to injection drug use began to rise. By the mid-1990s, almost 30% of HIV infections in the country were estimated to be the result of needle sharing and related sexual transmission.57

In Brazil, as elsewhere, the initial response of the public health system was constrained by criminal justice authorities who sought to interpret the issue as the province of the justice system rather than the public health system. Early attempts to implement needle exchange programs in the city of Santos and the state of São Paulo were met with extreme resistance, including threats to imprison public health officials promoting needle exchange programs. By the early 1990s, however, a process of negotiation had begun that involved representatives of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Justice, with behind-the-scenes support from a number of United Nations agencies. The result was the establishment of a task force to develop a national policy to respond to HIV and injection drug use. As part of the more general program of prevention initiatives developed for support from the World Bank, a set of pilot needle exchange and harm reduction programs were established and implemented in key cities across the country.1

In 1998, the state of São Paulo passed legislation authorizing the health department to buy and distribute sterile needles and syringes. The success of this publicly sponsored program led to similar legislation in other states, culminating in modifications to the Brazilian Law on Drugs that authorized the Ministry of Health to implement national harm reduction programs. Input from injection drug users has helped shape these programs. Whether as a direct result of these policies and programs or not, the percentage of AIDS cases linked to injection drug use had declined to 11% in 2003.6

It was a longer and more difficult process to build a public and governmental consensus that drug use should be addressed as a public health rather than criminal justice problem. As with other aspects of the NAP, certain themes and processes underlie that change: local initiatives at the municipal and state levels shaped the national program, a strong emphasis on human rights was the context for reaching out to an extremely marginalized population, free and universal HIV treatment was an incentive for injection drug users to access and stay in care, and active input from the target group itself helped create an effective program.1

PROGRAMMATIC LESSONS

While national and local context will fundamentally shape a country’s response to its AIDS epidemic, there are programmatic elements that public health planners must address in all countries. A critical analysis of the Brazilian approach, both its strengths and weaknesses, may give insights helpful to others.

Prevention

The SUS, for all its accomplishments, has not been the primary vehicle for HIV prevention efforts in Brazil. From the earliest days of the epidemic, civil society organizations (CSOs), in alliance with local governmental AIDS programs, have led the development and implementation of most prevention programs. The national government was slow to respond throughout the 1980s, and CSOs, primarily the newly formed AIDS NGOs, emerged as the most vocal and active critics of the federal government’s HIV policies. It was only as redemocratization proceeded and key personnel from some of the progressive state and municipal public health departments were brought into the Federal Health Ministry that collaborations at the national level developed.58 The lessons from the local initiatives based on nondiscrimination and solidarity began to shape the NAP.13

Perhaps the most crucial development in HIV control efforts in Brazil emerged from the prolonged (1992–1994) negotiation between Brazil and the World Bank over the terms of a large loan to help finance its response to the HIV epidemic. The successful negotiation of the US $160 million loan required active collaboration across many governmental ministries, active participation of CSOs through the NAP, and support from a wide range of political parties; it also required US $90 million in matching funds from the Brazilian Treasury. (Throughout this process, Brazil refused to conform to the World Bank demands that it halt the free distribution of azidothymidine, or AZT, a program it had started several years before.) The total program of US $250 million over 5 years financed a large-scale control effort capable of a major impact throughout much of the country.25,59

There are important lessons to be drawn from the experience of the first World Bank loan, as well as 2 subsequent loans.

Broad-based political support.

Key individuals in government committed to an aggressive response to HIV were politically adept enough to use the loan negotiation process to build support for the HIV control program across a wide range of governmental and nongovernmental sectors. Control of HIV became a national priority, even if implementation efforts largely remained within the Ministry of Health.

Adequate funding.

A large-scale prevention program capable of a major impact on the epidemic requires equally large-scale funding. As in many other areas of AIDS programming, half-hearted and inadequately funded programs are destined to fail.

Human resources.

Not only financial resources, but also human resources have been essential. There was a successful training program for human resources in and out of government, which had begun even before the World Bank loans but was intensified and expanded dramatically after the loans. There is an emphasis on health educators and a particular focus on peer educators, who serve as a natural link between the most vulnerable communities and the health system.

CSO involvement.

CSOs were involved throughout the process and helped shape a prevention program that funded a wide range of NGO-led initiatives. While there is some concern that governmental funding of NGOs compromises their willingness and capacity to criticize the government, there is little question that it has made it possible to reach many of the most vulnerable people in Brazil.43

HIV control efforts in Brazil are decentralized and multifaceted, but there are some significant generalizations, both positive and negative, about the prevention program. For example, the mass media (press, radio, television) has played a positive role in control efforts. Generally, stigma and stereotyping have been avoided, and there is an openness about sexuality and condom use that is not present in many other countries. However, the prevention program has not succeeded in stopping increasing rates of HIV infection among the poorest strata of society, particularly poor women. HIV prevention programs have not yet been integrated into other aspects of women’s health programs, such as family planning, treatment of sexually transmitted infections, and routine gynecological care. Programs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission have inadequate coverage for pregnant women despite the availability of testing and treatment.60 Perhaps most important, at least in terms of long-term sustainability, while the overall NAP addresses prevention, care, and treatment, the SUS has continued to view its primary responsibility as care and treatment. Prevention efforts have still not been fully integrated with care and treatment at the programmatic level in the SUS, and there is still not an effective interface between the SUS and the CSOs involved in prevention efforts.

Treatment

The Brazilian program of free, universal access to antiretroviral treatment has had a dramatic impact on morbidity and mortality from AIDS in Brazil and has gained considerable international recognition for its efforts. Since the Durban International AIDS Conference, the Brazilian government has offered free technical assistance to other countries developing similar programs. The following sections provide a few lessons that may be of value to other countries.

Integration of treatment and prevention.

The integration of care and treatment was fundamental to the Brazilian program even before the development of effective antiretroviral treatment. When AZT became available in the late 1980s, the state of São Paulo made small quantities available at no cost. The promise of treatment gave an incentive for more at-risk individuals to be tested and gave doctors an incentive to report AIDS cases, thus improving surveillance and prevention programs. The success of the São Paulo free drug program led to its adoption by other states and ultimately by the federal government. While AZT monotherapy was of limited value, it did create the principle that PLWHA have the right to free treatment.25,41

Universal access.

That Brazil’s treatment program is free has received considerable attention, but less publicized is the fact that it is universal. Universal distribution, in contrast to free medication solely in the public health sector, created many more points of access to treatment and allowed more rapid scale-up. Quite intentionally, it also eliminated the financial incentive for such corrupt practices as theft from central supplies or resale of medication by individuals. Free and universal distribution became a proactive solution to the potential development of a domestic black market for antiretrovirals.

Local manufacture.

The Brazilian program of universal, free access is financially viable in large measure because of Brazil’s capacity for local manufacture of pharmaceuticals. Local manufacture, particularly but not exclusively of generics, creates systemic downward pressure on patented drug prices and, importantly, avoids the currency fluctuations that make it extremely difficult for importing countries to project drug costs effectively. The domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity strengthens the government’s hand in its negotiations with the multinational pharmaceutical companies by enabling the government to issue a compulsory license if companies abuse their patent monopoly by pricing the drug out of the range of the Brazilian market.

Capacity to use complex therapies.

The Brazilian program is proof that health care systems outside the wealthy countries can effectively use complex therapies such as anti-retroviral treatment. Although less tangible than the manufacture of generic drugs, using complex therapies is as important a lesson for other countries with weak health care systems. The Brazilian treatment program was initiated as a vertical program guided by the NAP with its own administration, staff, logistical systems, and budget. This has resulted in ongoing difficulties in creating horizontal linkages within the SUS, but realistically it was the only way to rapidly establish and scale up the program. One of the major challenges in the last 4 to 5 years has been to decentralize this program within the SUS and at the state and municipal levels—a challenge that is accentuated owing to the continental size of the country.61

Creating international alliances.

The Brazilian government has acted proactively and strategically to protect the NAP from international pressures. As mentioned previously, Brazil firmly resisted World Bank demands that it drop its free distribution of AZT as a condition of the first loan agreement; it subsequently resisted threats from the United States to challenge Brazil’s generic manufacture of some antiretrovirals before the World Trade Organization. The NAP has also resisted pressure to change its open approach to the prevention of sexual transmission. Brazil has allied itself with other developing and poor countries to create a global consensus more favorable to health initiatives; these countries have led efforts to challenge the restrictive interpretation of the TRIPS (Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property) agreement, succeeded in having the United Nations Human Rights Commission declare access to treatment part of the human right to health, and helped forge a bloc of nations that made the right to treatment a prominent part of the Consensus Statement from the UN General Assembly Special Session on AIDS.

Like Brazil’s prevention record, Brazil’s success in integrating care and treatment into a unified approach to the control and mitigation of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is thus impressive. No one, not even the greatest supporters of the Brazilian program, would suggest that these achievements have come easily or that there is not still much important work to be done to strengthen existing programs and to ensure their sustainability over time. Political tensions that sometimes threaten to disrupt service provision are still all too common, particularly when different political parties or factions control municipal, state, and national health programs in Brazil’s federalist system of government.24 Logistics in relation to the distribution of medications is still often uneven, sometimes requiring aggressive interventions on the part of CSOs as well as the NAP.58 At least thus far, however, these challenges have been met with consistent success, in large part through partnership and collaboration between the Brazilian government and civil society. Brazil’s response to HIV and AIDS at every level has increasingly emerged as a model program that other health programs in Brazil seek to emulate and that other countries look to for inspiration as they seek to develop their own unique responses to the challenges posed by the epidemic.

Conclusions

Controlling the HIV/AIDS pandemic will likely be the greatest challenge to public health in the 21st century. HIV is a minuscule bit of RNA, but this viral event causes a profoundly human phenomenon. Modifying intimate experiences, changing established social relationships, and challenging global inequalities are all part of the response to HIV.

Brazil has done all of these things with some success; insights into the process can hopefully be of some value to all of us grappling with these concerns. There is a final lesson from Brazil that is worthy of notice: the NAP has become a source of national pride for the Brazilian people. It is “owned” by the government, civil society, the media, and, most importantly, people living with HIV. Solidarity and pride, it seems, may be the most effective counter to stigma. To control HIV, we must first admit that the problem belongs to all of us.

Acknowledgments

This article draws on data collected with support from the National Science Foundation (grant 1025–0440; principal investigator, R. Parker) and analyses developed with support from the Ford Foundation (grant BCS-9910339; principal investigator, R. Parker). Additional support for writing and analysis was provided through the International Core of the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (supported by center grant P30 MH43520 from the National Institute of Mental Health; principal investigator and center director, A. A. Ehrhardt; international core director, R. Parker).

Peer Reviewed

Contributors A. Berkman and R. Parker developed the initial draft of this article. All other authors helped to further refine the ideas and contributed to drafts of the article.

References

- 1.National Coordination for STD and AIDS. The Brazilian Response to HIV/AIDS. Brasília, Brazil: Ministry of Health; 2000.

- 2.Parker R, Passarrelli CA, Terto V, Pimenta C, Berkman A, Muñoz-Laboy M. The Brazilian response to HIV/AIDS: assessing its transferability. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27:140–142. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health of Brazil, National Coordination for STD and AIDS. Drugs and AIDS. The Brazilian Response to HIV/AIDS: Best Practices. Brasilia, Brazil: Ministry of Health; 2000:116–130.

- 4.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2004: changing history. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2004/en/report04_en.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2004.

- 5.Antonio de Ávila Vitória M. The experience of providing universal access to ARV drugs in Brazil. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27:247–264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coordenação Nacional de DST/AIDS. Boletim Epidemiológico AIDS, Ano XVIII. No. 01–01a–26a semanas epidemiológicas. Brasília, Brazil: Ministério da Saúde; January–June 2004.

- 7.Epidemiological Fact Sheets on HIV/AIDS and Sexually-Transmitted Infections, 2004, Update: Brazil. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2004.

- 8.Barreira D. Números e Tendências Atuais da Epidemia do HIV e AIDS. Brasília, Brazil: Ministério da Saúde; July 2004.

- 9.Parker R, Rochel de Camargo K Jr. Pobreza e HIV/AIDS: aspectos antropológicos e sociológicos. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2000;16(suppl 1):89–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniel H, Parker R. Sexuality, Politics and AIDS in Brazil: In Another World? London, England: Falmer Press; 1993.

- 11.Parker R. Introdução. In: Parker R, ed. Políticas, Instituições e AIDS: Enfrentando a Epidemia no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 1997:7–15.

- 12.Teixeira PR. Políticas públicas em AIDS. In: Parker R, ed. Políticas, Instituições e AIDS: Enfrentando a Epidemia no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 1997:43–68.

- 13.Galvão J. AIDS e activismo: o surgimento e a construção de novas formas de solidariedade. In: Parker R, Bastos C, Galvão J, Stalin Pedrosa J, eds. A AIDS No Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 1994:341–350.

- 14.Paiva V. Beyond magic solutions: prevention of HIV and AIDS as a process of psychosocial emancipation. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27: 192–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weyland K. Social movements and the state: the politics of health reform in Brazil. World Dev. 1995; 23(10):1699–1712. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weyland K. Obstacles to social reform in Brazil’s new democracy. Comp Polit. 1996;29(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weyland K. The Brazilian state in the new democracy. J Interamerican Stud World Aff. 1997;39(4): 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waitzkin H, Iriart C, Estrada A, Lamadrid S. Social medicine in Latin America: productivity and dangers facing the major national groups. Lancet. 2001; 358:315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paiva V, Ayres JR, Buchalla CM, Hearst N. Building partnerships to respond to HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2002;16(suppl 3):76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arretche M. Decentralização das Políticas Sociais no Estado de São Paulo. São Paulo, Brazil: Edições Fundap; 1998.

- 21.Monteiro de Andrade LO. SUS Passo a Passo: Normas, Gestão e Financiamento. São Paulo, Brazil: Editora Hucitec Ltda; 2001.

- 22.Elias PE, Cohn A. Health reform in Brazil: lessons to consider. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:44–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastos FI. A Feminização da Epidemia de AIDS no Brasil: Determinantes Estruturais e Alternativas de Enfrentamento. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 2001. Coleção ABIA: Saúde Sexual e Reprodutiva publication no. 3.

- 24.Parker R. Building the foundations for the response to HIV/AIDS in Brazil: the development of HIV/AIDS policy, 1982–1996. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27:143–183. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galvão J. AIDS no Brasil. São Paulo, Brazil: Editora 34; 2000.

- 26.Galvão J. As respostas das organizações não-governamentais brasileiras frente à epidemia de HIV/AIDS. In: Parker R, ed. Políticas, Instituições e AIDS: Enfrentando a Epidemia no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 1997:67–108.

- 27.Paiva V. Em tempos de AIDS. São Paulo, Brazil: Summus; 1992.

- 28.Parker R. Políticas, Instituições e AIDS: Enfrentando a Epidemia no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Zahar/ABIA; 1997.

- 29.Ventura M. Strategies to promote and guarantee the rights of people living with HIV/AIDS. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27:239–246. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heywood M. Current developments: preventing mother-to-child transmission in South Africa. S Afr J Health. 2003;19:278–315. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnett T, Whiteside A. AIDS in the Twenty-First Century: Disease and Globalization. New York, NY: Pal-grave Macmillian; 2002.

- 32.World Bank. World development indicators, GINI Index. 2004. Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/data/wdi2004. Accessed October 10, 2004.

- 33.Araújo de Mattos R, Terto V Jr, Parker R. World Bank strategies and the response to AIDS in Brazil. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27:215–246. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mamdani M. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1996.

- 35.Young C. The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 1994.

- 36.Amin S. Underdevelopment and dependence in black Africa: origins and contemporary forms. J Modern Afr Stud. 1972;10(4):503–524. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng L, Kostner M, Young C. Democratization and Structural Adjustment in Africa in the 1990s. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 1991.

- 38.Smith M. False hope or new start? The Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, TB and Malaria. Oxfam Briefing Paper, 2002. Available at: http://www.oxfam.org/eng/pdfs/pp0206_false_hope_or_new_start.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2005.

- 39.Raupp Rios R. Legal responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Brazil. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27:228–238. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latin American and Caribbean Council of AIDS Service Organizations (LACCASO). Report on Access to Comprehensive Care, Antiretroviral Treatment (ARVs) and Human Rights of People Living With HIV/AIDS in Latin America. Washington, DC: Inter-American Commission on Human Rights; October 2002.

- 41.Pinheiro R, Araújo de Mattos R. Os Sentidos da Integralidade: Na Atenção e no Cuidado à Saúde. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: UERJ; 2001.

- 42.Pinheiro R, Araújo de Mattos R. Construção da Integralidade: Cotidiano, Saberes e Práticas em Saúde. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: UERJ; 2003.

- 43.Passarelli CA, Terto V Jr. Non-governmental organizations and access to anti-retroviral treatments in Brazil. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate. 2003;27: 252–264. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arretche M. Graus de decentralização na municipalização do atendimento básico. In: Arretche M, ed. Estado Federativo e Políticas Sociais: Determinantes de Decentralização. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Revan; 2000: 197–239.

- 45.Parker R. Na Contramão da AIDS: Sexualidade, Intervenção, Politica. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 2000.

- 46.Zaluar AM. Exclusion and public policies: theoretical dilemmas and political alternatives. Revista Basileira de Ciências Sociais. 2000;1:25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaluar AM. Condomínio do Diabo. São Paulo, Brazil: Editora Brasiliense; 1996.

- 48.Fonseca C. Mãe é uma só? Reflexões em torno de alguns casos brasileiros. Psicologia USP. 2002;13(2): 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parker R. Bodies, Pleasures and Passions: Sexual Culture in Contemporary Brazil. Boston, Mass: Beacon Press; 1991.

- 50.Berquó E . Comportamento Sexual da População Brasileira e Percepções do HIV/AIDS. Brasília, Brazil: Ministério da Saúde; 2000.

- 51.Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Loan in the Amount of US $165 Million. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1998. Report 18338-BR.

- 52.US–Brazil Joint Venture on HIV/AIDS in Luso-phone Africa. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/06/20030620-14.html. Accessed June 20, 2003.

- 53.Girard F. Global Implications of US Domestic and International Policies on Sexuality. New York, NY: International Working Group on Sexuality and Social Policy; June 2004. Working paper no. 1.

- 54.Agência nacional de AIDS. Estados Unidos cancelam grande programa de combate à AIDS no Brasil. Available at: http://www.agenciaaids.com.br. Accessed September 2003.

- 55.Stoneburner RL, Low-Beer D. Population-level HIV decline and behavioral risk avoidance in Uganda. Science. 2004;304:714–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosenfield A, Figdor E. Where is the M in MTCT? The broader issues in mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:703–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Castilho EA, Chequer P. Epidemiologia do HIV/AIDS no Brasil. In: Parker R, ed. Políticas, Instituições e AIDS: Enfrentando a Epidemia no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 1997:17–42.

- 58.Passarelli CA, Parker R, Pimenta C, Terto V Jr. AIDS e Desenvolvimento: Interfaces e Políticas Públicas. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 2003.

- 59.World Bank. Acordo de Empréstimo (Projeto de Controle da AIDS e das DST) entre a República Federativa do Brasil e o Banco Mundial, 16 March 1994. Brasília, Brazil: Brazilian Ministry of Health; 1994.

- 60.Barbosa RM, Di Giacomo do Lago T. AIDS e direitos reprodutivos: para além da transmissão vertical. In: Parker R, ed. Políticas, instituições e AIDS: Enfrentando a Epidemia no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ABIA; 1997:163–175.

- 61.Westphal MF. Gestão de Serviços De Saúde: Decentralização, Municipalização do SUS. São Paulo, Brazil: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo; 2001.