Abstract

The growing use of social science constructs in public health invites reflection on how public health researchers translate, that is, appropriate and reshape, constructs from the social sciences. To assess how 1 recently popular construct has been translated into public health research, we conducted a citation network and content analysis of public health articles on the topic of social capital.

The analyses document empirically how public health researchers have privileged communitarian definitions of social capital and marginalized network definitions in their citation practices. Such practices limit the way public health researchers measure social capital’s effects on health. The application of social science constructs requires that public health scholars be sensitive to how their own citation habits shape research and knowledge.

Recent reports suggest that the integration of social science constructs into public health research will continue to increase in the coming years.1 While concepts such as socioeconomic status and culture have long been a part of the public health vernacular, one of the more recent newcomers has been social capital. Since Kawachi and colleagues’ 1997 essay “Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Mortality,”2 there has been a proliferation of articles devoted to the application and perceived utility of the concept of social capital in population health research. Definitions of social capital range from communitarian definitions, which focus on “features of social organization such as civic participation and trust in others,”2 to network definitions, which focus on social relationships and access to resources.

We present the results and conclusions of a citation network analysis and a citation content analysis conducted on the translation of the concept of social capital into public health research. We use the term “translation” rather than “integration” purposefully to refer to the semiotic processes associated with the movement of ideas and concepts across academic boundaries and the structures of authority that emerge through these migratory processes.3 Whereas integration or transfer suggests that ideas remain intact as they cross from the social sciences to public health, the notion of translation suggests that ideas may be reshaped as they cross boundaries and become embedded in different institutional contexts and intellectual paradigms.

With the promise that social science holds for health research come important challenges.4 One such challenge is for public health professionals and researchers to remain critically reflective about the processes by which social science is translated into the public health mainstream. How do public health researchers translate social science concepts into research and practice? How does this translation affect the meaning and application of those concepts? One means by which public health researchers might remain critical of their application of social science constructs is to reflect on one of the most basic of academic activities—citation practices. The academic practices of researchers require that researchers know the research and literature in which they specialize. They draw upon that literature as they write journal articles or grant applications, or promote their programs and activities to colleagues, policy-makers, and the public more generally.

Although skeptical of certain articles in the field or perhaps even the literature more generally, scholars are required to exhibit knowledge of that literature, particularly those articles considered seminal. However, what constitutes the “field” or an area of specialization is not simply an amorphous collection of articles. Instead, it is a collection of articles with a particular structure, a structure that emerges from the citation practices of the scholars who engage in that field. It is a structure that elevates the prominence and visibility of certain theoretical and methodological approaches while marginalizing others. In short, citation practices constitute a “knowledge–construction” process that shapes the way we think about and engage with our research. Analyses of these practices have revealed the cognitive structure of research fields, the prominence of certain articles and scholars, and the developmental history of disciplines and areas of specialization.5–7

The analysis of the citation practices surrounding the translation of social capital into public health requires us to think about public health research, practice, and knowledge in a manner in which we may not be accustomed. Rather than viewing research as an objective, apolitical endeavor, our analysis underscores the ways in which intellectual authorities and hierarchies emerge through seemingly mundane and everyday activities, such as writing and citing articles. While there are political implications that can be gathered from such an analysis, our intention is not to deconstruct public health knowledge but to demonstrate the practices by which that knowledge becomes shaped, and the implications that these shapes have for the way in which public health translates and applies social science in health research.

With the exception of Navarro’s general critique of what he refers to as the “communitarian approach” to social capital8 and Fassin’s discussion of the conceptual limitations of social capital in epidemiology,9 little has been written about the actual processes and academic practices surrounding public health’s translation of social capital. The continued relevance and growth of public health as a field, however, requires a willingness to reflect critically on how translation processes transpire and how public health knowledge emerges from various types of social practices and institutions. In so doing, a deeper understanding of how social contexts affect health might be fostered.

WHY SOCIAL CAPITAL?

To understand the translation of social science into public health, we reviewed the literature on social capital and health. Although the exact origins of the concept are disputed, social capital was first developed within the social sciences to refer to an individual’s reliance on and use of interpersonal relationships to access resources or achieve certain socially desired ends. As with economic capital, one could invest in social capital and use it to increase one’s social position in a community or society.10 In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the concept became revitalized through the work of Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, and Robert Putnam, each of whom approached social capital from a different perspective.11

Bourdieu examined the complex interplay of economic capital, cultural capital, and social capital, emphasizing the interchangeability of these different forms of capital and their unequal distribution among individuals and groups in society.11–14 Coleman’s rational choice alternative concentrates on social capital, positing network closure (i.e., the degree to which actors in a network are connected) as a mechanism that accounts for social capital effects.11,13,15,16 While important differences exist between the works of the sociologists Coleman and Bourdieu, each approaches the study of social capital in terms of the resources found or accessed through a person’s social relationships.11,13

Whereas Coleman and Bourdieu provide an avenue to what might be considered “network” approaches to social capital, the work of the political scientist Robert Putnam has been associated with what is referred to as the communitarian approach.8 Within that approach, social capital is seen as “the features of social life—networks, norms, and trust—that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions.”17 Although Putnam included the notion of networks in his definition, he did not provide the type of structural analysis offered by Bourdieu and Coleman. Instead, Putnam’s analysis focused solely at the group or community level, tending to equate social capital with the degree of civic engagement or amount of trust in a community.13

Compared with its history in the social sciences, the concept of social capital appeared only recently in health studies. There was, however, a remarkable zeal around its early use in the public health mainstream. The concept first appeared in the title of a public health article in the September 1997 issue of the American Journal of Public Health. In “Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Mortality,”2 Kawachi and colleagues propose that social capital might operate as a mediating variable between income inequality and mortality. In other words, high levels of social capital lessen the impact of income inequality on the health of populations. Two months later, in the November issue of the American Prospect, a magazine with a broader audience, Kawachi, Kennedy, and Lochner associate social capital with public health in the title to their article, “Long Live Community: Social Capital as Public Health.”18

The appearance of social capital in public health literature has sparked considerable debate around a number of concerns. Debates focus on such questions as (1) does the concept of social capital adequately answer questions of power and intracommunity inequalities,19–23 (2) is social capital a more accurate predictor of variations in health outcomes than economic and income-related factors,23–26 (3) which methods and measures might best capture the concept of social health,25–27 and (4) which geographic level of analysis (e.g., national, state, or community) provides the most utility for public health research.28–30 Although these are important points of debate in their own right, what has largely gone unnoticed is how public health has reshaped the concept of social capital to fit within the intellectual paradigms of public health.

The fact that there appears to be no clear consensus in the social and political sciences on what social capital is, how it should be measured, or how it is to be understood stands in stark contrast to the apparent consensus found in the public health literature on social capital. The relative absence of public health research using network approaches to measure social capital raises important questions about the marginalization of alternative conceptualizations of social science constructs as they become translated into public health. Through an empirical analysis of the citation practices of public health researchers, we demonstrate how those practices have reduced social capital to its communitarian guise. In so doing, our goals are to increase the visibility of alternative approaches and reinvigorate the study and relevance of social capital for public health research.

METHODS

Citation Analyses

To examine the processes surrounding the translation of social capital into public health, we undertook a citation network analysis and a citation content analysis of public health articles on social capital. The citation network analysis allows us to describe the structure of the literature on social capital, revealing those articles that have been more prominent and influential. The citation content analysis allows us to track how those articles cite the work of Putnam, Coleman, and Bourdieu. A citation may be seen as a “concept symbol” that represents an author’s orientation to a larger school of thought or approach to a topic.31 The citation analyses allow us to view the structure of the public health literature that has emerged from current citation practices and show how this emergent structure elevates certain perspectives and approaches while marginalizing others.

Specification of the Article Population

Before beginning the citation analyses, we had to specify the boundaries around both public health literature and the articles within that literature that focus on social capital. We restricted our analysis to the PubMed database, which contains over 30000 journals and includes access to MEDLINE, the US National Library of Medicine’s bibliographic database. The MEDLINE database covers the fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, the health care system, and the preclinical sciences and contains over 12 million citations dating back to the mid-1960s. Although coverage is worldwide, most records are from English-language sources.32

The search was conducted in January and February 2003 and was restricted to articles with “social capital” in their titles, because social capital is probably the most central topic covered in those articles.33 The search revealed 87 articles published between January 1997 and December 2002. After eliminating non–English-language articles and articles unrelated to social capital,34 the original population of 87 articles was reduced to 65 articles. These 65 articles comprised the “social capital” article population. (This list of articles is available upon request from the corresponding author.)

For each article in the sample, we documented basic attribute data: number of authors/ coauthors, authors with more than one article in the population, and number of articles by teams of authors.

In addition, the 65 articles were classified into 1 of 3 types: reviews, empirical pieces, or commentaries. On the basis of previously established definitions,35 an empirical piece was an article involving analysis of data, observation, or experience (including measurement development); a review was a general survey, critical evaluation, or revised study of material previously examined; and a commentary was a systematic series of explanations or interpretations of the literature (distinguished from a review in that it did not survey the literature).

Network Analysis

After classifying each article, we examined each article’s references to determine if any of the other 64 articles in the population were cited. The citation network was based on the citation ties found to exist among the 65 articles. Because our primary focus was on the structure of the article network and the influence of particular articles, our analysis does not correct for autocitation. Following the collection and input of the citation network data, centrality scores for each article were determined and a main path analysis of the network data was conducted.

Centrality.

Centrality scores were determined for each article. Centrality measures the visibility or prominence of actors in a network at a specific moment in time.36,37 For this analysis, centrality provides a cross-sectional look at the state of the literature as of the end of 2002. In a network containing directed ties (e.g., “cites” or “is cited by”), a distinction can be made between in-degree and out-degree centrality. In-degree centrality measures the prominence of certain articles in terms of being cited, while out-degree centrality measures the prominence of articles in terms of citing other articles. Our analysis focused on the more prominent articles as measured through in-degree centrality—that is, those articles that are more central in terms of being cited by other articles. We calculated Freeman in-degree centrality scores for each article by using the network analysis software package UCINET (Analytic Technologies, Harvard, Mass).

Main path.

A main path network analysis was conducted on the citation data to map the development of the “social capital” public health literature over time.34 The main path through a citation network is the path with the highest traversal counts.5,7,38 Traversal counts measure the number of times that a tie or link between articles is involved in connecting other articles in a citation network.39 The main path analysis determines all possible search paths through the network, starting with an origin article and continuing through to endpoint articles, and it calculates the traversal counts of each link in the network.34,39 Unlike the analysis of centrality, which is time sensitive, the main path analysis provides a longitudinal perspective on how a research field has evolved according to its citation patterns. The main path analysis was conducted with the software package PAJEK (available from Vladimir Batagelj at: http://vlado.fmf.uni-lj.si/pub/networks/pajek/default.htm).40

Citation Content Analysis

In addition to the citation network analysis, a citation content analysis was conducted on the 65 articles to examine how frequently the work of Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, and Robert Putnam was cited and the category of these citations. The content analysis began with a simple count of the number of times each author was cited in each article. We then examined the citation style. We used a factorial design to randomly assign 33 (51%) of the 65 articles to each author of this study. This ensured that each article was read and coded independently at least twice. We coded the articles on the basis of how the article’s author(s) cited the work of Bourdieu, Coleman, and Putnam. Citations of these scholars could fall into 1 of 3 categories: (1) substantive, (2) supplementary, or (3) passing. The coding scheme was developed on the basis of previous work in the field of citation analysis.41

Substantive citations were viewed as those meeting 2 criteria: (1) having additional comment and (2) being integral to the way that the author(s) of the article conceptualize or measure social capital, regardless of whether we viewed the citation as an accurate reflection of Bourdieu’s, Coleman’s, or Putnam’s work. Supplementary citations were seen as those in which Bourdieu, Coleman, or Putnam were referred to with additional comment, but without the citation being integral to the conceptualization or measurement of social capital. Passing citations were viewed as those failing to meet both criteria 1 and 2.

If one of these scholars was cited more than once, the code assigned was on the basis of the most intensive manner in which the scholar was cited. For example, if an article cited Putnam 6 times—4 times in passing, once in a supplementary manner, and once substantively—we classified that article’s citation of Putnam as being substantive. If that same article also cited Coleman twice but both times only in passing, then we classified that article’s citation of Coleman as passing. Initially, we were in agreement in 74% of the cases, with a κ score of 0.54, meaning fair to good agreement beyond chance. Differences in interpretation were mainly between substantive or supplementary uses of Coleman or Putnam. Such differences occurred primarily in commentaries and revolved around whether those scholars were integral to the author’s remarks on social capital. Where there was disagreement between pairs of raters, the final code assigned to an article’s citation of Putnam, Coleman, or Bourdieu was on the basis of consensus among all 4 authors of this study.

Integrated Network and Content Analysis

Following the coding of citations and classification of articles, the individual citation networks for Putnam, Coleman, and Bourdieu were constructed on the basis of those articles in which they were each cited substantively. Their individual substantive-citation networks were examined along the following dimensions: (1) network size, (2) the presence of highly central articles in the network, (3) the presence of articles found on the main path of literature development, and (4) the density or degree of connectivity among the articles. Highly central articles were defined as those articles with centrality scores at least twice the average centrality score. Density is a proportional measure of the number of ties present in a network over the number of all ties possible in a network.

RESULTS

There were a total of 126 authors and coauthors of the 65 articles included in the citation network, an average of 1.94 authors per article. The authorship frequency data reveal that the literature is dominated by a relatively few number of authors who mainly come from social epidemiology backgrounds. Of the 126 authors, 18 have published more than one article as either first author or coauthor. There are 8 authors who have been first author of more than one article. Taken together, those 8 authors are listed on the bylines of 19 of the 65 articles (29%). Baum, Kawachi, and Veenstra were each lead author of 3 articles, and together they are listed on the bylines of 14% of the articles. Two pairs of authors have published more than 2 articles together: Lynch and Muntaner with 3 and Kawachi and Kennedy with 6.

Of the 65 articles, 39 were empirical pieces, 4 were reviews, and 22 were commentaries. Putnam’s work was the most frequently cited work in the 65 articles, followed by Richard Wilkinson’s Unhealthy Societies,42 which is cited 18 times. Portes’s 1998 article, “Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology,” printed in the Annual Review of Sociology,13 despite having an important impact on the development of the concept in sociology, is cited only 8 times in the 59 articles published after 1998.

Citation Network Analysis

Centrality.

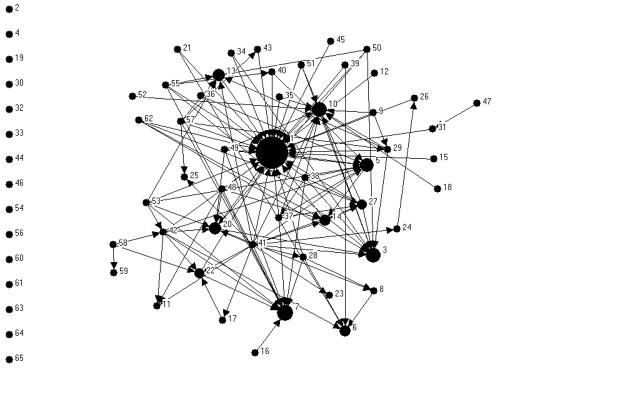

Figure 1 ▶ presents the citation network for the 65 articles in the study. There were 15 articles isolated from the rest of the citation network, which means that those articles did not cite and were not cited by any other articles in the citation network. The mean centrality score for the entire network is 1.9, which implies, roughly speaking, that each article in the population was cited on average by 2 other articles. Highly central articles were thus considered to be those with a centrality score greater than or equal to 4. The most prominent article in the network is “Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Mortality,”2 with an in-degree centrality score of 34, almost 3 times higher than the second most prominent article in the network (Table 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Citation network for the 65 articles in the study.

Note. Circles represent articles; the larger the circle, the higher the article’s in-degree centrality score. Arrows represent citations to other articles. Isolated articles (n = 15) appear on the left side of the figure.

TABLE 1—

Eleven Most Frequently Cited Articles on Social Capital in the Primary Citation Population

| Rank | Article | In-Degree Score |

| 1 | (1) “Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Mortality” (Kawachi et al., 1997)2 | 34 |

| 2 | (7) “Social Capital: Is It Good for your Health? Issues for a Public Health Agenda” (Baum, 1999)19 | 12 |

| 3 | (3) “Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Firearm Violent Crime” (Kennedy et al., 1998)44 | 11 |

| 4 | (10) “Social Capital and Self-Rated Health: A Contextual Analysis” (Kawachi, Kennedy, and Glass, 1999)46 | 11 |

| 5 | (5) “Social Capital and Health: Implications for Public Health and Epidemiology” (Lomas, 1998)43 | 8 |

| 6 | (13) “Social Capital: A Guide to Its Measurement” (Lochner, Kawachi, and Kennedy, 1999)25 | 6 |

| 7 | (20) “Social Capital and Health Promotion: A Review” (Hawe and Shiell, 2000)20 | 6 |

| 8 | (6) “Children Who Prosper in Unfavorable Environments: The Relationship to Social Capital” (Runyan et al, 1998)45 | 5 |

| 9 | (14) “Home Is Where the Governing Is: Social Capital and Regional Health Governance” (Veenstra and Lomas, 1999)26 | 5 |

| 10 | (22) “Social Capital—Is It a Good Investment Strategy for Public Health?” (Lynch et al., 2000)21 | 4 |

| 11 | (27) “Social Capital, SES and Health: An Individual-Level Analysis” (Veenstra, 2000)47 | 4 |

Note. Numbers preceding citations are identification numbers of the circles (representing articles) in the network diagram (see Figure 1 ▶). Most-frequently-cited articles are articles with an in-degree centrality score of 4 or above.

Main path.

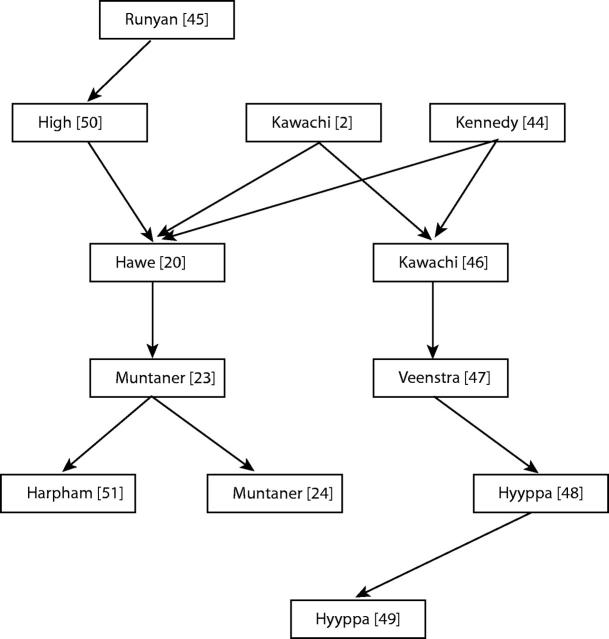

Figure 2 ▶ shows the main path of development of the “social capital” literature in public health. The analysis shows 3 roots to the literature and 2 branches along which it has developed. The 3 roots or original sources for the literature are Kawachi et al., “Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Mortality”2; Kennedy et al., “Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Firearm Violent Crime”44; and Runyan et al., “Children Who Prosper in Unfavorable Environments: The Relationship to Social Capital.”45

FIGURE 2—

Main path of the development of literature on social capital, 1997 to 2002.

Note. Boxes show first author of each article and its citation number in the References section of this article.

Articles on both branches of the main path consist primarily of empirical pieces, and most cite Putnam in a substantive manner. However, there are 2 differences worth noting about the 2 branches. First, the right branch consists entirely of empirical pieces while the left branch holds a review article and a commentary. Second, the right branch cites Putnam and Coleman in either a substantive or supplementary manner with only 1 passing citation of Bourdieu, while the left branch has 2 articles that cite Bourdieu substantively. These 2 articles are also the review and commentary pieces.

Citation Content Analysis

Table 2 ▶ presents the results of the citation content analysis. Our analysis of the citation frequency of Bourdieu, Coleman, and Putnam revealed that Robert Putnam was the most frequently cited and the most often cited in a substantive fashion. James Coleman ranked second in both those categories, while Pierre Bourdieu was the least frequently cited and the least often cited in a substantive fashion. Once cited, Putnam’s work was almost 5 times more likely to be used in a substantive rather than in a passing manner.

TABLE 2—

Citation Content Analysis of Articles Citing the Works of Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, and Robert Putnam

| Total No. of Citations | Total No. of Articles in Which Cited | No. of Articles Classified as Substantive Citations | No. of Articles Classified as Supplementary Citations | No. of Articles Classified as Passing Citations | |

| Bourdieu | 25 | 14 | 7 | 1 | 6 |

| Coleman | 70 | 30 | 11 | 3 | 16 |

| Putnam | 190 | 48 | 36 | 4 | 8 |

The differential application of Putnam, Coleman, and Bourdieu is also apparent in how these scholars were cited in empirical pieces, reviews, and commentaries. Putnam was cited substantively in 23 empirical pieces, 4 reviews, and 9 commentaries. Coleman was cited substantively in 7 empirical pieces, 2 reviews, and 2 commentaries. Bourdieu was cited substantively in 3 empirical pieces, 2 reviews, and 2 commentaries. Putnam was thus the most influential scholar of the three on the basis of an empirical application of the concept of social capital to health research.

Integrated Citation Network and Citation Content Analysis

The individual citation networks of Putnam, Coleman, and Bourdieu were based on the articles in which each was cited substantively. They differed along 4 dimensions. In terms of network size (i.e., the number of articles that cited the scholar in a substantive manner), Putnam had 36 articles, Coleman 11, and Bourdieu 7. Along the second dimension—the presence of highly central articles in the network—Putnam had 7 articles, Coleman 2, and Bourdieu 1. In terms of articles found on the main path, Putnam again had the highest number with 8, while Coleman and Bourdieu each had 2. Neither of the articles belonging to Bourdieu’s substantive network that were located on the main path developed a network approach in an empirical manner.

Along the final dimension—the density or degree of connectivity among the articles—Putnam’s network was the densest, with a density of 0.1222. Coleman’s substantive citation network had a density of 0.0900. Bourdieu’s network, by contrast, was completely disconnected (density = 0). Unlike those referring to Putnam and Coleman, the articles referring to Bourdieu in a substantive manner did not cite or develop the work of other articles using Bourdieu in the same manner as did articles citing Putnam and Coleman.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that a small number of articles dominate the public health literature on social capital. While the average article centrality score is 1.9, there are 11 articles with twice the average centrality score. The most prominent article—the 1997 paper by Kawachi and colleagues—has a centrality score of almost 17 times the average. Rather than the citation structure reflecting a high degree of interconnectivity among the articles and the development of a range of perspectives, scholars are citing and relying on this one article as the main authority in the field. The literature has developed as either a further elaboration of the approach to social capital presented in the 1997 article or in specific reaction to its characterization of social capital.

The analysis also reveals the impact of Robert Putnam on the way in which social capital has been translated into public health research. The way in which public health researchers have thought about and engaged social capital is one in which the communitarian approach has had a preponderant influence. The hegemony of the communitarian approach can be seen not only in the content of the public health literature (i.e., the frequent and substantive use of Robert Putnam) but also in its structure (i.e., the centrality and main path position of those articles that use Putnam substantively). In contrast, network approaches as represented in citations of Coleman and Bourdieu have become both marginalized and fragmented. For example, our analysis reveals not only that Bourdieu is infrequently cited but that there is only 1 highly central article that cites him in a substantive manner and only 2 articles (neither an empirical piece) that are on the developmental path of the literature. In addition, articles that have used Bourdieu substantively remain disconnected from one another. One of the consequences of such fragmentation is that there is no development or growth in the application and use of network perspectives within the public health literature. Coleman’s work has been more influential than that of Bourdieu, but neither has had the influence of Putnam’s work in shaping the way public health engages with the concept of social capital.

In his work on the nature of scientific knowledge, Latour refers to the power and strength of citations in constituting scientific “facts.” An article that fails to cite other articles, or is not frequently cited by them, is more vulnerable to criticism than is an article that cites, or is cited in a supportive manner by, a large number of articles. To criticize a well-cited article requires scholars to engage with all the other studies to which that article is connected.3 Articles that are more central in the literature tend to appear more authoritative and less vulnerable to criticism than those that are more marginal. Regardless of an article’s intrinsic merits, its authority emerges through the way that it is connected to other articles in the field.

The fact that the conceptualization and measurement of social capital in public health has been based so heavily on the work of Robert Putnam has implications for the way in which the concept evolves in the public health domain. For example, reviews and articles on social capital and health have questioned the utility of the concept for health research, stressing not only the mixed results of studies examining the relationship between social capital and health but also the concept’s weaknesses in resolving inequalities and power.19,21,23,24,52 While such criticisms may be well-founded, they may be misplaced: a case of blaming the concept when it is the way that the concept has been translated and operationalized in public health. Indeed, when seen from a network perspective that emphasizes social ties and an individual’s access to resources through those relationships,12,13,53 the concept of social capital highlights topics concerning the unequal distribution of power and of access to valued social resources. One of the problems that critics of social capital in public health must confront is the difficulty in moving beyond its most visible “communitarian” formulation in order to advance these alternative approaches.

What has emerged from the translation of social capital into public health is a conceptualization that largely ignores network approaches. The marginalization of alternative approaches has meant that the various debates surrounding social capital’s relevance for health research have failed to consider the concept in its rich complexity and depth. This has led to a premature disenchantment with the concept and its utility for health research. For example, one of the debates in the social sciences surrounding social capital is whether social capital should best be understood as an individual-level or a community-level variable.13 Within public health, however, there is no such debate: social capital is seen as the property of neighborhoods and, more specifically, as a collective asset or public good.2 Without a debate on the most appropriate level or method of analysis, we may inaccurately conclude that the concept is ill-equipped to resolve inequalities in health among individuals, communities, and populations.

Our analysis of the citation practices surrounding the translation of social capital in public health shows how a particular conceptualization has emerged through those practices. The analysis reveals a structure to the literature that promotes and legitimizes certain approaches while marginalizing others; one that makes visible certain scholars, journals, and institutions while obscuring others; and one that shapes the way we think about and measure social capital.

The implications of such an analysis for current public health practice are numerous. First, it reminds us that knowledge is socially constituted. Our understanding of the effects of social capital on health is a product of the manner in which the concept is being translated into public health. To emphasize the social production of knowledge, however, is not to deconstruct public health research or the effects of social processes on individual or population health. Instead, it is meant to demonstrate the complexities of research by showing how the way we come to think about and use concepts are shaped in part by the disciplines and fields in which we are located. Second, by integrating network and content analysis methods, we have shown how networks act as important contexts that structure the position of actors in a population and have demonstrated the continued relevance of using network methods to examine the emergence of structures of authority and influence in society.

In mapping out how network approaches to social capital have been marginalized in public health, we seek to reinvigorate the concept of social capital and highlight the concept of social networks for studying the effects of social contexts on health. The marginality of network approaches is not because of their lack of relevance or validity but because of the disproportionate weight and authority given to communitarian approaches. Communitarian approaches conform well to public health’s tendency to envision social contexts in terms of bounded places, and such approaches to social capital have served to reinforce that vision. Although convenient in terms of current data availability, the defining of social contexts on the basis of census geography makes the analysis of social processes and dynamics difficult.54–56 (There are additional empirical burdens associated with the inclusion of network items in national surveys, but the inclusion of such items is both feasible and beneficial.57) Rather than assuming the presence or absence of “community” based on political-administrative criteria, one of the benefits of network approaches is that they leave open as an empirical question whether a specific social aggregate is a community or not.58–60

Thinking about social capital in terms of networks thus reorients our perspectives toward the structure of social relationships and highlights the influence of nonspatial contexts on individual and population-level health. Research using network approaches has shown networks to be important contexts influencing health outcomes and has successfully examined concerns regarding the asymmetric distribution of power, influence, and access to resources.61 Researchers may choose to circumscribe certain networks by using spatial markers (e.g., individuals within certain villages or towns) to examine networks within particular places.62–64 Nevertheless, such an approach views social contexts primarily in network terms and then secondarily in terms of the geographical areas in which they are embedded.

There is a complexity and depth to the concept of social capital and social networks that has yet to be fully explored and exhausted in public health research. The development of alternative approaches calls for scholars to interact with the whole range of controversies in a field and to be increasingly conscious of how citation practices influence the way in which knowledge develops. To accurately and effectively translate such controversies into public health research implies that we must first be aware of these controversies, which may require that we search beyond commonly used public health bibliographic databases and indices. It is an endeavor that asks researchers and practitioners to be sensitive to the ways in which public health translates social science into research and practice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through funding from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research in the form of a postdoctoral fellowship (to S. Moore) and senior scholarships (to A. Shiell and P. Hawe).

We thank Almaymoon Mawji for his assistance in collecting and assembling the citation articles.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors S. Moore originated the study and led the analyses and writing. A. Shiell, P. Hawe, and V.A. Haines assisted with the study and the analyses. All authors helped to conceptualize ideas, interpret findings, and review drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Bachrach CA, Abeles RP. Social science and health research: growth at the National Institutes of Health. Am J Public Health. 2004;1:22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, Prothow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1491–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latour B. Science in Action. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1987.

- 4.Williams HA, Jones C, Alilio M, et al. The contribution of social science research to malaria prevention and control. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80: 251–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hummon N, Doreian P, Freeman L. Analyzing the Structure of the centrality-productivity literature created between 1948 and 1979. Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization. 1990;11:459–480. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Small H. Cited documents as concept symbols. Soc Stud Sci. 1978;8:327–340. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hummon N, Carley K. Social networks as normal science. Soc Networks. 1993;15:71–106. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro V. A critique of social capital. Int J Health Serv. 2002;32:423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fassin D. Social capital, from sociology to epidemiology: critical analysis of a transfer across disciplines. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2003;51:403–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitten N. Network analysis in Ecuador and Nova Scotia: some critical remarks. Can Rev Sociol Anthropol. 1970;7(4):269–280. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuller T, Baron S, Field J. Social capital: a review and critique. In: Baron S, Field J, Schuller T, eds. Social Capital: Critical Perspectives. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2000:1–38.

- 12.Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson JG, ed. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York, NY: Greenwood; 1985: 241–258.

- 13.Portes A. Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociol. 1998;24: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calhoun C. 1993. Habitus, field, and capital: the question of historical specificity. In: Calhoun C, Postone M, LiPuma E, eds. Bourdieu: Critical Perspectives. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press; 1993:61–88.

- 15.Coleman J. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman J. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1990.

- 17.Putnam R. Making Democracy Work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1993.

- 18.Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Lochner, K. Long live community: social capital as public health. Am Prospect. 1997;35:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baum F. Social capital: is it good for your health? Issues for a public health agenda. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:195–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawe P, Shiell A. Social capital and health promotion: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:871–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch J, Due P, Muntaner C, Smith GD. Social capital—is it a good investment strategy for public health? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54: 404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore S, Daniel M, Linnan L, Campbell M, Benedict S, Meier A. After Hurricane Floyd passed: investigating the social determinants of disaster preparedness and recovery. Fam Community Health. 2004;27: 204–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muntaner C, Lynch J, Smith GD. Social capital, disorganized communities, and the third way: understanding the retreat from structural inequalities in epidemiology and public health. Int J Health Serv. 2001; 31:213–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muntaner C, Lynch JW, Hillemeier M, et al. Economic inequality, working-class power, social capital, and cause-specific mortality in wealthy countries. Int J Health Serv. 2002;32:629–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lochner K, Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Social capital: a guide to its measurement. Health Place. 1999;5(4): 259–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veenstra G, Lomas J. Home is where the governing is: social capital and regional health governance. Health Place. 1999;5(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cattell V. Poor people, poor places, and poor health: the mediating role of social networks and social capital. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(10):1501–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altschuler A, Somkin C, Adler N. Local services and amenities, neighborhood social capital, and health. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1219–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browning CR, Cagney KA. Neighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self-rated health in an urban setting. J Health Soc Behav. 2002; 43:383–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klinenberg E. Dying alone: the social production of urban isolation. Ethnography. 2001;2:501–531. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen B. Referring schools of thought: an example of symbolic citations. Soc Stud Sci. 1997;27:937–949. [Google Scholar]

- 32.NCBI PubMed Overview. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/overview.html. Accessed January 2003.

- 33.Whittaker J, Courtial JP, Law J. Creativity and conformity in science: titles, keywords and co-word analysis. Soc Stud Sci. 1989;19:473–496. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore S, Shiell A. “Social capital” in public health research. University of Calgary Centre for Health and Policy Studies Working Papers. Available at: http://www.chaps.ucalgary.ca/papers.htm. Accessed September 2004.

- 35.MacInko J, Starfield B. The utility of social capital in research on health determinants. Milbank Q. 2001; 79:387–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman L. Centrality in social networks. Soc Networks. 1979;1:215–239. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hawe P, Webster C, Shiell A. A glossary of terms for navigating the field of social network analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:971–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hummon N, Doreian P. Connectivity in a citation network: the development of DNA theory. Soc Networks. 1989;11:39–63. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hummon N, Doreian P. Computational methods for social network analysis. Soc Networks. 1990;12: 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batagelj V, Mrvar A, Zaversnik M. Network analysis of texts. Working paper. Available at: http://vlado.fmf.uni-lj.si/pub/networks/pajek. Accessed January 2003.

- 41.Chubin DE, Moitra S. Content analysis of references: adjunct or alternative to citation counting? Soc Stud Sci. 1975;5:423–441. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkinson R. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. New York, NY: Routledge; 1996.

- 43.Lomas J. Social capital and health: implications for public health and epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47: 1181–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kennedy B, Kawachi I, Prothrow-Stith D, et al. Social capital, income inequality, and firearm violent crime. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Runyan DK, Hunter WM, Socolar RR, et al. Children who prosper in unfavorable environments: the relationship to social capital. Pediatrics. 1998;101:12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Glass R. Social capital and self-rated health: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1187–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veenstra G. Social capital, SES and health: an individual-level analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50: 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hyyppa MT, Maki J. Individual-level relationships between social capital and self-rated health in a bilingual community. Prev Med. 2001;32:148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyyppa MT, Maki J. Why do Swedish-speaking Finns have longer active life? An area for social capital research. Health Promot Int. 2001;16:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.High P, Hopmann M, LaGasse L, et al. Child centered literacy orientation: a form of social capital? Pediatrics. 1999;103:e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harpham T, Grant E, Thomas E. Measuring social capital within health surveys: key issues. Health Policy Plann. 2002;17:106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pearce N, Davey-Smith G. Is social capital the key to inequalities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93: 122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin N. Social Capital: Theory and Research. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 2001.

- 54.Tienda M. Poor people and poor places: deciphering neighborhood effects on poverty outcomes. In: Haber J, ed. Macro-Micro Linkages in Sociology. New-bury Park, Calif: Sage; 1991.

- 55.Grannis R. The importance of trivial streets: tertiary street networks and geographic patterns of residential segregation. Am J Sociol. 1998;103:1530–1564. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sampson R, Morenoff J, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;28: 443–478. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burt R. Network items and the general social survey. Soc Networks. 1984;6:293–339. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bender T. Community and Social Change in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1978.

- 59.Wellman B. The community question: the intimate networks of East Yorkers. Am J Sociol. 1979;84: 1201–1231. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berkman L, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman T. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levy J, Pescosolido B, eds. Social Networks and Health. New York, NY: Elsevier Science; 2002.

- 62.Kapferer B. Strategy and Transaction in an African Factory. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press; 1972.

- 63.Boissevain J. Hal-Farrug: A Village in Malta. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1979.

- 64.Hirdes J, Scott K. Social relations in a chronic care hospital: a whole network study of patients, family and employees. Soc Networks. 1998;20:119–13w. [Google Scholar]