Abstract

Objectives. We conducted 5 surveys on consumer and provider perspectives on access to dental care for Ohio Head Start children to assess the need and appropriate strategies for action.

Methods. We collected information from Head Start children (open-mouth screenings), their parents or caregivers (questionnaire and telephone interviews), Head Start staff (interviews), and dentists (questionnaire). Geocoded addresses were also analyzed.

Results. Twenty-eight percent of Head Start children had at least 1 decayed tooth. For the 11% of parents whose children could not get desired dental care, cost of care or lack of insurance (34%) and dental office factors (20%) were primary factors. Only 7% of general dentists and 29% of pediatric dentists reported accepting children aged 0 through 5 years of age as Medicaid recipients without limitation. Head Start staff and dentists felt that poor appointment attendance negatively affected children’s receiving care, but parents/caregivers said finding accessible dentists was the major problem.

Conclusions. Many Ohio Head Start children do not receive dental care. Medicaid and patient age were primary dental office limitations that are partly offset by the role Head Start plays in ensuring dental care. Dentists, Head Start staff, and parents/caregivers have different perspectives on the problem of access to dental care.

Head Start programs have shown the challenges low-income families encounter when trying to meet the dental needs of their pre-school children. Today, Early Head Start and Head Start (EHS/HS) services extend to eligible infants and children aged 0 through 5 years of age, pregnant women, and their families when family income is below 185% of the federal poverty level.1 Although the primary target is low-income families below 100% of the federal poverty level or those receiving specific types of public assistance, up to 10% of slots can be used for children whose families exceed the low-income guidelines (over-income enrollees). Local Head Start programs determine eligibility priorities, including enrollment criteria for over-income enrollees. In addition, 10% of enrollment slots (regardless of income) are to be filled by children with disabilities.2 During much of the 1990s, Head Start programs and parents of Head Start children nationwide reported access to dental care as their number one health concern.3

Nationally, all Head Start programs operate under a set of performance standards requiring that the program staff determine, in collaboration with parents, each child’s oral health status within 90 days of that child’s entry into the program. Therefore, the staff must determine whether the child has a continuous accessible source of dental care (“dental home”) and, if not, staff must assist parents in finding a source of care where a dental professional will determine whether the child is up to date on the Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment program schedule of age-appropriate preventive and primary care services. If children have no dental home, the program staff must assist parents in scheduling dental appointments for the children and in arranging for further examination and dental treatment for children in need of dental care; the program has a plan in place for monitoring follow-up care for children identified as needing dental treatment.4

Most Head Start children are eligible for dental care through Medicaid and its Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment program or the State Children’s Health Insurance program. In Ohio, this State Children’s Health Insurance program is an eligibility extension of the Medicaid program (up to 200% of the federal poverty level) rather than separate from it. In 2002–2003, approximately two thirds (62%) of Ohio EHS/HS children were enrolled in Medicaid, yet the Head Start Program Information Report, an annual mandatory self-report by local EHS/HS programs, revealed that 45% of those in need of dental treatment were not receiving treatment.5

There are many different types of impediments that EHS/HS program staff encounter in order to get dental care for their enrolled children, some of which are beyond the programs’ control, such as the number of proximate dentists and Medicaid policy issues. Other obstacles, however, may be easier to overcome with persistence, education, and community partnerships involving the Head Start program. These hindrances include parental attitudes and behaviors about oral health and dental care, cultural beliefs and health practices, language differences, fears, educational levels, and negative attitudes that many dentists and their staffs have about treating low-income children covered by Medicaid.6,7

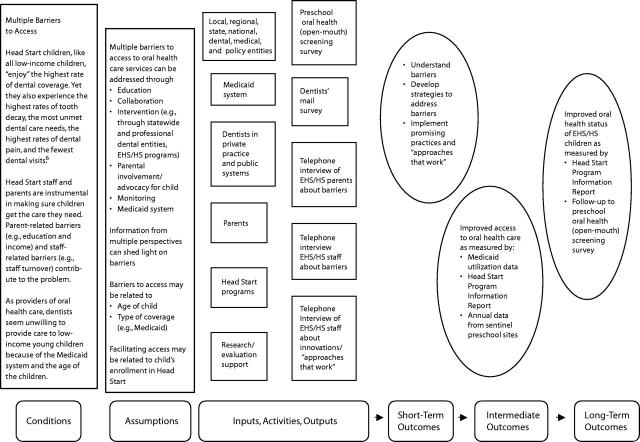

In 2002–2003, the Ohio Department of Health began a project to improve oral health and access to dental care for the state’s approximately 58 000 Head Start children. The department developed a logic model (Figure 1 ▶) to illustrate how access to dental care is a multifaceted concern involving parents, Head Start staff, and the dental care delivery system (mostly private practitioners).

FIGURE 1—

Logic model for access to dental care for Head Start children.

Note. EHS/HS = Early Head Start/Head Start.

We describe the findings of a series of 5 surveys designed to test the logic model’s assumptions and to better understand parental, Head Start staff, and dental care provider perspectives on the multifaceted problem of access to dental care for Head Start children. Two of the surveys have been described in greater detail elsewhere.8,9 In addition, we analyzed geocoded addresses to supplement information taken from the surveys.

METHODS

We collected information from 4 groups—Head Start children, their parents or caregivers, Head Start staff, and primary dental care providers—using the surveys described in the following sections.

Open-Mouth Screening Survey

We conducted oral screenings for 2555 children aged 3 through 5 years at 50 Ohio Head Start centers during the 2002–2003 school year with probability-proportional-to-size sampling. In addition, we analyzed parental responses to 6 access-oriented questions on the consent form. Data were weighted and analyzed with Stata software (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). A more detailed description of the survey methodology has been reported elsewhere.8

Mail Survey

We sent the mail survey to primary care dentists, that is, general and pediatric dentists, and safety net dental clinics (safety net clinics are those clinics for people who do not have a regular dentist but do know that their Medicaid card will be accepted or that they will not be turned away if they cannot afford services).

A random sample of 13% of the state’s 4984 general dentists and 72% of the 139 pediatric dentists received a pretested 22-question survey, mailed in late 2002. In addition, we sent a separate mailing to all Ohio safety net dental clinics, with the exception of those known to limit care to nonpediatric populations.

The safety net dental clinics surveyed were categorized into 3 groups:

Noninstitutional general practice, for example, local health departments and federally qualified health centers (SN-General)

Pediatric dentistry specialty practices, usually affiliated with teaching hospitals or dental schools (SN-Ped) (Clinics that had at least some care provided by pediatric dentists or residents, on a regular basis, were categorized as pediatric dentistry.)

General practice residency (GPR) and advanced education in general dentistry (AEGD) programs affiliated with hospitals or dental schools (SN-GPR/AEGD)

In the analysis, responses for general dentists in private practice were considered according to years since graduation and geographic character (e.g., urbanized, rural) of their practices. Greater detail on survey methods is available elsewhere.9

Comparison of Head Start With Dental Care Provider Locations

Although this was not a survey per se, we used geocoded data to compare the locations of practices of the state’s primary care dentists in the licensure database of the state dental board with the locations of safety net dental clinics and Head Start centers. To ensure that the addresses listed in the dental board’s database were offices rather than homes, we compared the list with an Ohio Dental Association membership renewal list. We reconciled discrepancies by researching on-line listings and making telephone calls to dental offices. We established the geographic character of private practice respondents with ArcView GIS, version 3.3 software (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, California). We used census definitions10 to categorize dentists into 4 mutually exclusive geographic classifications at the census tract level (Table 1 ▶).

TABLE 1—

Distribution of Survey Respondents, All Ohio General and Pediatric Dentists, Head Start Centers, and Safety Net Dental Clinics, by Geographic Character Classification: 2002–2003

| General Dentists | Pediatric Dentists | Head Start Centers | Safety Net Dental Clinicsc | |||

| Geographic Character Classificationa | Survey (n = 351),% | All Ohio General Dentists (n = 4860), %b | Survey (n = 58),% | All Ohio Pediatric Dentists (n = 131), %b | All (n = 835), % | All (n = 72), % |

| Urbanized area, central cityd | 25.4 | 27.2 | 20.6 | 21.4 | 44.3 | 58.4 |

| Urbanized area, not central citye | 50.7 | 51.3 | 67.2 | 67.9 | 18.1 | 9.7 |

| Urban cluster, not central city (rural, small city)f | 17.4 | 15.0 | 12.1 | 7.6 | 19.4 | 19.4 |

| Ruralg | 6.6 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 18.2 | 12.5 |

aPopulation calculated by census tract.

bLicensed dentists who were able to be geocoded.

cSafety net dental clinics providing services to children aged 0 through 5 years.

dCentral city = the largest place in a metropolitan statistical area or consolidated metropolitan statistical area; sometimes there is more than 1 central city per metropolitan statistical area or consolidated metropolitan statistical area. Central cities are essentially contained within urbanized areas.

eUrbanized area = urban nucleus of 50 000 or more people; population density of 1000/mi2; could have adjoining territory with 500/mi2.

fUrban cluster = population of 2500 to 50 000; built-up territory around small towns and cities.

gRural = all areas that are not urbanized areas/urban clusters; population < 2500; towns and villages.

Telephone Interview Surveys of Head Start Staff

After adjustment for duplicates, pilot test participants, and disconnected telephones, 82 of the 87 Ohio EHS/HS programs identified in the directory of the regional Head Start quality network contractor were contacted by telephone, and 60 interviews were completed. Depending on each Head Start health coordinator’s answers to 2 filter questions, the actual number of questions ranged from 6 to 16, most of which were open ended. The questions related to systems or approaches that worked to provide dental care.

A convenience sample of 15 of the 82 Head Start grantee or delegate agencies was drawn to represent EHS/HS programs by geographic locations in Ohio (i.e., north, south, east, west, and central). Grantee and delegate agencies generally have many Head Start centers, totaling 835 in Ohio. Health coordinators at the sample centers participated in a 13-item structured telephone interview survey about their perceptions of children’s oral health care needs and how those needs were met.

Telephone Interview Survey of Parents/Caregivers of Head Start Children

We asked the interviewed Head Start health coordinators to identify 3 to 5 families who had children in Head Start programs. We sent parents information about participation in an 11-item structured interview survey about dental care for their children and asked them to return written consent to be contacted for telephone interviews. The first parent to be reached by telephone from each of the 15 sites was included in the study.

RESULTS

The surveys confirmed and quantified some of the underlying conditions assumed by the Head Start Dental Care Access Logic Model and revealed some varied perspectives on other concerns, many of which are summarized in Table 2 ▶.

TABLE 2—

Comparison of Ohio Consumer and Provider Perspectives on Dental Care Access Concerns for Head Start (HS) Children: 2002–2003

| Access Concerns | Consumer Perspectives: HS Staff and HS Parents and Caregivers | Provider Perspectives: General Practice Dentists (GPs), Pediatric Dentists (PDs), and Safety Net Dental Clinic Dentists (SNDCs)a |

Access to dental care is a problem for low-income families

|

HS parents and caregivers:

|

Dentists strongly or somewhat agreed that low-income families have significant difficulty obtaining dental care:

|

| Dentist factors | ||

| Most general dentists won’t see young children | HS parents and caregivers (60%) and HS staff (67%) said it is more difficult to find dentist than a doctor (physician) to care for HS childrend,e HS staff cited problems with the dentists’ inability to treat young childrend |

34% of GPs reported seeing patients aged 0 through 2 years of age in the past year 91% of GPs reported seeing patients aged 3 through 5 years of age in the past year |

| Pediatric dentists and SNDC dentists are more likely to treat young children, HS children, and Medicaid patientse | 54% of HS parents or caregivers whose child had a dental visit reported visits to be with a PDe | 100% of PDs reported seeing patients aged 0 through 2 years of age and aged 3 through 5 years of age in the past year 65% of all SNDCs reported seeing patients aged 0 through 2 years of age in the past year 97% of all SNDCs reported seeing patients aged 3 through 5 years of age in the past year |

| Many general dentists who see young children are not willing to provide more than examinations or cleanings | 67% of HS staff strongly or somewhat agree it is difficult to find dentists to provide fillings or extractions for their childrend | Among specific dental services, GPs reported being least willing to provide complex restorative care (46% not willing before child is aged 4 years), extractions (39%), and simple restorative care (26%) 39% of GPs reported that they will only provide examinations and cleanings for HS children |

| Dentists do not accept Medicaid patients aged 0 through 5 years of age, especially new patients | HS parents or caregivers and HS staff often reported dentists’ unwillingness to accept Medicaid as a hindrance to accessing cared,e,f | 22% of all GPs accept Medicaid patients aged 0 through 5 years of age, but only 7% do so without limitations 69% of all PDs do same, 29% without limitations 94% of all SNDCs do same, 81% without limitations |

| Head Start parent/caregiver factors | ||

| HS parents or caregivers do not know how to access dental care | HS parents and caregivers disagreed that this was a concerne | … |

| HS parents or caregivers do not value dental care sufficiently | 67% of HS staff somewhat or strongly agreed that parents do not value oral health care for their childrend No HS parents or caregivers considered this an impediment to their children getting caree |

For Medicaid patients, dentists strongly or somewhat agreed that parents and caregivers do not sufficiently value dental care:

|

| HS parents or caregivers find it difficult to get to dental appointments (e.g., child care, transportation, leaving work) | HS parents and caregivers (40%) and HS staff (67%) identified difficulties in getting to dental appointments as impediments to getting dental cared,e | Dentists identified missed or late appointments as the most common problem that might limit their treatment of Medicaid patients:

|

| Head Start factors | ||

| HS staff help to get their program’s children into dental care | All interviewed HS staff reported assisting parents and caregivers to gain access to dental care for their childrend 40% of interviewed HS parents or caregivers reported receiving HS staff assistancee |

Some GPs (18%) and PDs (13%) said they were more willing to see Medicaid children if they were in HS |

| HS programs do not adequately prioritize oral health and dental care | 73% of HS staff somewhat or strongly disagreed that there was inadequate time to make dental care a priorityd 80% of HS staff felt that their program was able to meet oral health needs of children they served |

… |

aMail survey of Ohio general (n = 351) and pediatric (n = 58) dentists and safety net dental clinics (n = 72), 2002–2003.9

bOhio HS oral health screening survey, 2002–2003 (n = 2555).8

cQuestionnaire taken by parents and caregivers of HS children participating in HS oral health screening survey (n = 2435).8

d Telephone interview surveys of Ohio HS staff (perceptions [n = 15]; and approaches that have been effective in assuring access to dental care for EHS/HS children [n = 60]), 2002–2003.

e Telephone interview survey of Ohio HS parents or caregivers, 2002–2003 (n = 15).

fOnly 8% of parents and caregivers of Medicaid children who could not get needed care stated that the reason was an inability to find a dentist who accepted Medicaid.c

Unmet Dental Care Needs/Receipt of Dental Care

The findings of the oral health survey are described in greater detail elsewhere.8 Overall, 28% of the 3- to 5-year-old Head Start children screened had dental caries, and 12% of the 3-year-old children had evidence of early childhood caries. Parents who reported that their children could not get desired dental care were more likely to be uninsured and White.8

Head Start Parent/Caregiver Perceptions

Interviewed parents indicated that they encountered impediments when they tried to obtain dental care for their children, specifically the unavailability of dentists, particularly those who accepted Medicaid; the cost of dental care, when uninsured; problems getting to the appointment (e.g., work, child care, transportation); and long waiting times for appointments.

These factors were confirmed by the parent questionnaire for children screened in the open-mouth survey. The parents who reported that during the previous 12 months their children could not get desired dental care most often indicated that the main reason was cost of care or lack of insurance (34%) followed by factors relating to the dental office (20%), such as inconvenient hours, long waiting times, dentist availability, and difficulty getting an appointment.

Head Start Staff Perceptions

Head Start Program Staff who were interviewed reported helping parents sign up for Medicaid and access dental care for their children. The type of assistance included partnering with local providers or making arrangements for special clinics; having Head Start program staff take the child, with parental permission, to a dentist; facilitating the entire dental appointment process (e.g., preparing the child for the first visit, locating a dentist, making an appointment, and providing child care and transportation); locating dentists or providing a list of dentists who accept Medicaid; and paying for dental care.

Most Head Start parents interviewed reported that the program taught them how to take care of their child’s teeth, and almost half reported that the program helped them get dental care for their child.

Head Start staff agreed with parents that finding dentists who accept Medicaid, accept young children as patients in their offices, and provide more than examinations and cleanings are the primary hindrances to receiving dental care for their children. A number of respondents in rural counties said that some local dentists would do examinations and cleanings but would refer the children to children’s hospitals that generally were located a great distance away and had long wait times for children requiring sedation or general anesthesia for more complex care.

The approaches that Head Start health coordinators identified as most effective were those that were labor intensive and relied on partnerships and on building relationships with local dentists and dental clinics.

Dental Care Providers’ Proximity to Head Starts

Table 1 ▶ shows that although Ohio’s Head Start programs and safety net dental clinics are most often located in central city portions of urbanized areas, half of general dentists and two thirds of pediatric dental practices were in urbanized areas, not central city (roughly equivalent to suburban).

Dental Care Provider Perceptions

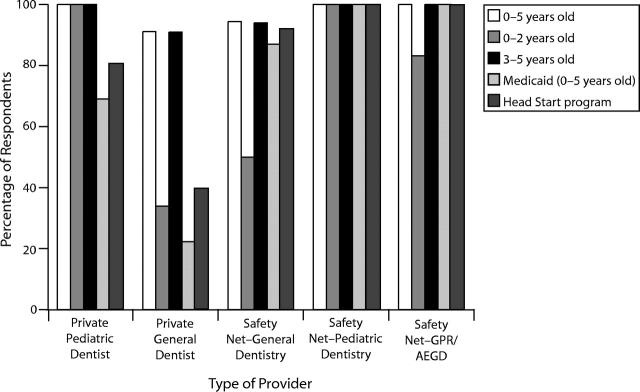

The adjusted response rate for the survey of private practice dentists was 63.2% and for safety net dental clinics was 100%. Figure 2 ▶ summarizes dentists’ treatment of young children, those whose care is paid for by Medicaid, and those enrolled in Head Start. Pediatric dentists, who represent less than 3% of Ohio dentists, generally are willing to provide almost all types of dental care to children, regardless of the child’s age. The safety net programs that have pediatric dentists or GPR/AEGD residents are most similar to private pediatric dentists in their willingness to treat young children, whereas the general safety net clinics are more like general dentists in this regard.9

FIGURE 2—

Ohio primary dental care providers’ treatment of young children during the preceding 12 months.

Source. Siegal and Marx.9 Note. GPR/AEGD = General Practice Residency/Advanced Education in General Dentistry program.

Pediatric dentists were approximately twice as likely as general dentists to have treated a Head Start child in the past 12 months. Essentially all the safety net clinics provided care to Head Start children. Although more than 90% of general dentists reported a willingness to provide diagnostic, preventive, and emergency care to 3-year-old children, fewer were willing to provide restorative care and extract teeth. More than one third of general dentistry sites (general dentists = 39%, SN-General = 36%) limited care for Head Start children to examinations, with or without referral.9 Pediatric dentists, with few exceptions, reported providing the majority of Head Start children with both examinations and restorative care, as did essentially all pediatric and GPR/AEGD safety net clinics.9

Dentists indicated a number of factors that limit their treatment of young children, the most common being the disruption that behavior problems cause in their offices. The greatest limitation on the pediatric dentistry safety nets and the GPR/AEGD safety net clinics was their capacity to accept any new patients.9

Table 2 ▶ indicates the small percentage of dentists (7% of general dentists and 29% of pediatric dentists) who reported accepting Medicaid patients without limitation. Although most dentists who treated Medicaid patients indicated more than 1 factor for limiting their entry into the practice, the single most common limitation for general dentists was to accept patients of record but not new patients (40%), and the most common limitation for pediatric dentists was that they only took referred patients (35%). Fifteen percent of pediatric dentists who treated Medicaid enrollees did not accept new Medicaid patients.9

The differences between Ohio general dentists based on years since graduation and on the geographic character of their practices were not dramatic.9

Enrollment in Head Start appears to make dentists in private practice somewhat more willing to see a young child whose care is paid for by Medicaid.9

DISCUSSION

Although impediments to dental care access for Head Start children have been described elsewhere,6 the Ohio surveys quantified the problems and compared perspectives of parents and caregivers, providers, and Head Start staff. Making significant inroads remains a challenge in the face of geographic disparity between consumers and providers, as well as the disparity of each faction’s perspectives on some of the underpinning dental care access concerns. It is clear that a large number of Ohio Head Start children are not having their dental care needs met. Our surveys tended to be about 10 percentage points higher than self-reported Ohio Program Information Report data5 for Medicaid eligibility, dental visits, and need for dental care. Although all surveyed groups shared the perception that access to dental care is a problem for low-income families, including those with children in Head Start, they did not all agree on the causes.

Although widely used, the term access to dental care lacks a standard definition. Many health professionals assume that linking children with a dental home will ensure the receipt of such care, resulting in good oral health.11–13 Even with our cross-sectional surveys and Head Start Program Information Report data, we could not measure the establishment of a dental home, because the current definition implies a continuous relationship between the child and the dental home.14 Our surveys, however, demonstrated that linkage to a dental office often does not meet the dental home definition.

It is not surprising that Head Start programs and safety net clinics tend to be located near low-income populations (e.g., central city portions of urbanized areas) whereas private dental offices are more likely to be in more suburban areas. Although this lack of proximity of dental offices may be another hindrance, it did not appear to be a primary issue and was not likely to be influenced by Head Start programs.

The greatest access-to-dental-care problem that Head Start children face is that Medicaid pays for the dental care of two thirds to three fourths of all children enrolled in Head Start. Most dentists who accepted Medicaid also limited their participation, most often closing their doors to new patients. Typical reasons that dentists offered for not treating Medicaid recipients can be grouped into 2 primary categories: administrative issues (e.g., low fees, slow payment, difficulty in getting questions answered) and client behaviors.15,16 The Ohio survey of dentists identified client behaviors (i.e., appointment keeping and timeliness) as the more significant reasons.

Enrollment in Head Start had a positive effect on Medicaid-eligible children visiting the dentist. Ohio’s Medicaid program reported that in the 2001–2002 fiscal year, 34% of 3- to 5-year-old children enrolled in Medicaid at some time during the year had a dental visit (the proportion increased to 42% for those enrolled for at least 11 months).17 The percentage of Medicaid-eligible Head Start children whose parents or caregivers reported a dental visit was roughly double that rate (85%). Furthermore, dentists reported a greater willingness to provide some services for children whose care was paid for by Medicaid if they were also in Head Start. Parents and staff confirmed that Head Start programs play an active role in ensuring that children have dental visits. Surprisingly, although parents and caregivers enrolled in EHS/HS programs and EHS/HS staff were quick to identify finding a dentist who accepted Medicaid as a problem, only 8% of surveyed parents and caregivers who said they could not get needed dental care for their Medicaid child identified locating a dentist who accepted Medicaid as the main problem.

The gap between referral to a dentist and establishment of a dental home also relates to many dentists’ lack of interest in providing comprehensive care for young children, at least in part because of the perceived disruption to their offices. This problem is much greater for children younger than 3 years, whom only one third of general dentists saw in their offices, mostly for examinations and emergency care. Pediatric dentists (whose work is dedicated to children) and safety net dental clinics (whose mission is largely to serve low-income and Medicaid populations) are more likely to provide care for Head Start children than general dentists, but numbers of both are too small to meet the need.

The challenge for Head Start programs is to win the hearts and minds of local primary care dentists, a feat that has been accomplished by some Head Start staff with some individual dentists but rarely has been accomplished systemwide. Although pediatric and general dentists share dissatisfaction with various aspects of the Medicaid program and patient behaviors, pediatric dentists were more than 3 times as likely as general dentists to treat Medicaid patients. Unfortunately, if Head Start programs are to meet performance standards, they will need considerable help from general dentists, who far outnumber pediatric dentists and safety net clinic dentists. This resource could be strengthened by getting more pediatric dentists to treat Medicaid children and more general safety net dental clinics to become comfortable in providing comprehensive care for young children.

Our surveys indicate that while Head Start staff understand the provider problems in providing dental care for children in their programs, they also see that the solution with the greatest potential impact—for many more general dentists to accept Medicaid—is a policy matter that they can only hope to influence. In the meantime, Head Start staff, then, are left with the slow and frustrating 1-dentist-at-a-time and 1-parent/caregiver-at-a-time approach. Although some Head Start programs have had significant success in developing individual dentist champions, doing so requires ongoing effort and becomes more difficult when there is the significant staff turnover that many Head Start programs experience.

The differences in perspectives highlighted in this article are fundamental to the resiliency of the frustrations experienced by providers, Head Start staff, and parents and caregivers. Although dentists and Head Start staff questioned parents’ commitment to the oral health of their children, the interviewed parents and caregivers did not. It is difficult to distinguish the extent to which broken appointments reflect a lack of caring rather than legitimate challenges that families encounter, such as getting time off work and arranging transportation for dental appointments. For example, a North Carolina study of caregivers for Medicaid-insured children reported that caregivers were often discouraged and exhausted from their attempts to obtain dental care for their children. Focus group participants identified significant impediments such as finding providers, obtaining convenient appointment times, and securing transportation, as well as additional hindrances in the dental office such as long waiting times and judgmental, disrespectful, and discriminatory behavior from staff and providers.18

The primary limitations of our surveys, as with all such surveys, are the extent to which the responses reflect the true attitudes and behaviors of the various target groups and the extent to which those surveyed were representative of the entire population. The latter limitation was of more concern because of the small convenience sample of Head Start staff and, potentially even greater, of the parents, who may have been identified by Head Start staff because of their relative reliability or willingness to provide feedback. Furthermore, the survey questions, several of which had been used in previous surveys, were not validated. Geocoding by census tract, rather than block groups characterized by median family income, may have obscured differences between dentists’ attitudes and practices and disparities between the locations of Head Start programs and dental care resources.

In conclusion, many Ohio Head Start children do not receive needed dental care. Dental offices that have limitations on accepting young patients and patients whose care is paid for by Medicaid is the primary difficulty that is only partly resolved by the positive role Head Start staff play in ensuring dental care. Dentists, Head Start staff, and parents and caregivers have different perspectives on the access problem.

Acknowledgments

Partial support for this project was provided by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services (grant 4H47MC00011–04).

The authors thank Donna M. Ruiz, University of Cincinnati Early Childhood Learning Community; Karen Ludwig, University of Cincinnati Evaluation Services Center; Deborah Anania Smith, University of Cincinnati Evaluation Services Center; Debbie Zorn, University of Cincinnati Evaluation Services Center; Jessica Metzger, University of Cincinnati; and Kenneth R. Plunkett, Ohio Department of Health.

Human Participant Protection The surveys described in this article were all approved by the institutional review board of the Ohio Department of Health.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors M.D. Siegal originated the series of surveys, oversaw the contracts for their implementation and analysis, worked on the interpretation of the findings, and wrote the article. M.L. Marx conducted the surveys, analyzed the data, and drafted portions of the article. S.L. Cole assisted with the development of the survey instruments, was the primary liaison with the contractor during the data collection phase, and assisted with the preparation of the article.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Head Start Bureau Web site. About Head Start. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/hsb/about/index.htm. Accessed June 3, 2003.

- 2.National Archives and Records Administration. Chapter XIII, Office of human development services, department of health and human services. Part 1305, Eligibility, recruitment, selection, enrollment, and attendance in Head Start (codified at 45 CFR §1305). Code of Federal Regulations. Available at: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_04/45cfr1305_04.html. Accessed May 10, 2005.

- 3.Brocato R. Head Start and Partners Forum on Oral Health. Head Start Bull. 2001;71:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Head Start Bureau Web page. Head Start Program Performance Standards and Other Regulations. Available at: www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/hsb/performance/index.htm. Accessed June 3, 2003.

- 5.Head Start Program Information Report. Washington, DC: Administration for Children and Families, Head Start Bureau; 2004. Report 2002–2003.

- 6.Edelstein BL. Access to dental care for Head Start enrollees. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60:221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt K, Cole S. Oral Health Tip Sheet for Head Start Staff: Working With Parent to Improve Access to Oral Health Care. Washington, DC: National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center; 2003. Available at: http://www.mchoralhealth.org/PDFs/HSOHTipPro.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2004.

- 8.Siegal MD, Yeager MS, Davis AM. Oral health status and access to dental care for Ohio Head Start children. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:519–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegal MD, Marx ML. Ohio dentists’ treatment of young children. J Am Dent Assoc. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.US Census Bureau. Census 2000 Geographic Terms and Concepts. Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/www/tiger/glossry2.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2003.

- 11.American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement. Oral risk assessment timing and establishment of the dental home. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1113–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Dental Association. ADA statement on early childhood caries (Trans 2000:454). Available at: http://www.ada.org/prof/resources/positions/statements/caries.asp. Accessed June 22, 2004.

- 13.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Clinical guideline on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance and oral treatment for children. Pediatr Dent. 2003:25(suppl 7):61–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the dental home. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25(suppl 7):12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.US General Accounting Office. Report to Congressional Requesters, September 2000. Oral health factors contributing to low use of dental services by low-income populations. GAO/HEHS-00–149. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/he00149.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2004.

- 16.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General. Children’s Dental Services Under Medicaid—Access and Utilization (OEI-09–93–00240; 04/96). Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-93-00240.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2004.

- 17.Office of Ohio Health Plans. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio Department of Job and Family Services; 2004.

- 18.Mofidi M, Rozier RG, King RS. Problems with access to dental care for Medicaid-insured children: what caregivers think. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]