Abstract

Objective. We examined the timeliness of vaccine administration among children aged 24 to 35 months for each state of the United States and the District of Columbia.

Methods. We analyzed the timeliness of vaccinations in the 2000–2002 National Immunization Survey. We used a modified Bonferroni adjustment to compare a reference state with all other states.

Results. Receipt of all vaccinations as recommended ranged from 2% (Mississippi) to 26% (Massachusetts), with western states having less timeliness than eastern states.

Conclusions. Vaccination coverage measures usually focus on the number of vaccinations accumulated by specified ages. Our analysis of timeliness of administration shows that children rarely receive all vaccinations as recommended. State health departments can use timeliness of vaccinations along with other measures to determine children’s susceptibility to vaccine-preventable diseases and to evaluate the quality of vaccination programs. States can use the modified Bonferroni comparison to appropriately compare their results with other states.

In the United States, the childhood immunization schedule recommends that children receive approximately 15 vaccinations by 19 months of age, and it specifies ages for administration of each vaccine dose.1 These ages were selected to maximize protection as early as possible while minimizing potential risks.1

Each year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes state-specific vaccination coverage rates.2–4 State health departments use this information to assess the level of susceptibility of children residing in their state to vaccine-preventable diseases and to evaluate their vaccination programs. These vaccination rates typically focus on the number of vaccinations accumulated by the time of evaluation, which is conducted at age 19 to 35 months. With the exception of varicella, for which doses are included only if given after 12 months of age, these reports do not consider whether the vaccinations were given at appropriate ages. Children who are fully vaccinated at the time of the interview may have received some vaccinations too early for the vaccines to be effective, or they may have been undervaccinated during much of their first 2 years, when children are most susceptible to severe illness and complications from many vaccine-preventable diseases.

In 2002, a national-level study found that although 73% of children received all vaccinations in the standard 4:3:1:3:3 series by age 19 to 35 months,2 only 13% of children received all of these vaccinations at the recommended ages.5 Similar information at a state-specific level will enable state vaccination program administrators to evaluate timeliness of vaccinations for children and to compare the state’s rates of timely vaccination with that of other states. Our study examined state-level timeliness of vaccine administration, and we present a statistically appropriate method for comparing rates of 1 state with all other states.

METHODS

National Immunization Survey

Data on vaccination coverage among children aged 19 to 35 months in the United States are obtained annually from the National Immunization Survey (NIS). The NIS uses random-digit-dialing methods to survey households with age-eligible children; this is followed by a mail survey to the children’s vaccination providers to validate vaccination histories (subjects provide verbal consent). To increase sample sizes for each state, we combined data from the 2000, 2001, and 2002 surveys.

NIS data were analyzed on the basis of children in households interviewed (Council of American Survey Research Organizations response rates: 78.7% in 2000, 76.1% in 2001, and 74.2% in 2002) who have adequate vaccination history from their vaccination provider(s) (67.4% in 2000, 70.4% in 2001, and 67.6% in 2002). We further restricted our analysis to the 70% of children sampled who were at least 2 years of age at the time of the interview to assess vaccinations obtained during the first 2 years of life. In total, we analyzed data for 47 672 children aged 24 to 35 months (545–3160 children in each state and the District of Columbia). The NIS uses a variety of weighting strategies to reduce bias and to ensure that children included in the analysis are representative of all children in the United States. These strategies include (1) poststratification so that totals match Vital Statistics estimates for each state with respect to maternal education, race/ethnicity, and age group of the child6,7; (2) accounting for households without telephones by weighting those with interruption in telephone service8; and (3) using response propensities to adjust for vaccination provider nonresponse.9 Details of the NIS methods, including institutional review board approval for analysis of NIS data, are reported elsewhere.6,7

Outcome Measures

Vaccination doses recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Family Physicians during the period that children in our study were younger than 2 years old (1997–2002) included 4 doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular or whole-cell pertussis vaccine (DTP), 3 doses of polio-virus vaccine, 1 dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine (MMR), 3 or 4 doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine (Hib), 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine, and 1 dose of varicella vaccine.10 When we combined data from multiple survey years, we assumed that there were no important secular trends; data from the combined years were treated as a random sample from some larger population. Because coverage levels for most vaccinations are relatively stable over time,4 this is a reasonable assumption. However, varicella coverage is noticeably increasing over time; thus, we excluded varicella from this analysis. Additionally, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and influenza vaccine have recently been added to the early-childhood vaccination schedule.10–12 Because these recommendations did not apply to all children during the study period, they were not included in our analysis. We evaluated all the other recommended doses listed above and the combined series of these doses, which is called the 4:3:1:3:3 series.

We analyzed receipt of vaccine doses in accordance with the schedule approved by the ACIP, which includes recommended ages for routine administration (Table 1 ▶). Age recommendations listed on the schedule in months and weeks were converted to days. Because the number of days in a month varies, we considered each recommended age range as beginning at the fewest number of days and ending at the greatest number of days that comprised the given number of months. For example, the recommended age of 2 months equated to an age range of 59 through 91 days. This broad interpretation of the recommendations may have slightly overestimated the number of children who were vaccinated at the recommended ages.

TABLE 1—

Recommended and Minimum Ages for Early Childhood Vaccinationsa

| Vaccination Dose | Recommended Age for Routine Administration | Minimum Acceptable Ageb | Minimum Acceptable Intervalc |

| Hepatitis B | |||

| 1 | 0–2 months | Birth | |

| 2 | 1–4 months | 4 weeks | 4 weeks |

| 3 | 6–18 months | 6 months | 8 weeks |

| DTPd | |||

| 1 | 2 months | 6 weeks | |

| 2 | 4 months | 10 weeks | 4 weeks |

| 3 | 6 months | 14 weeks | 4 weeks |

| 4 | 15–18 months | 12 months | 4 months |

| Haemophilus influenzae type b | |||

| 1 | 2 months | 6 weeks | |

| 2 | 4 months | 10 weeks | 4 weeks |

| 3e | 6 months | 14 weeks | 4 weeks |

| 4 | 12–15 months | 12 months | 8 weeks |

| Poliovirus | |||

| 1 | 2 months | 6 weeks | |

| 2 | 4 months | 10 weeks | 4 weeks |

| 3 | 6–18 months | 14 weeks | 4 weeks |

| Measles-Mumps-Rubella | |||

| 1 | 12–15 months | 12 months | |

| Varicella | |||

| 1 | 12–18 months | 12 months | |

aApproved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

bDoses given within 4 days before the minimum age for all vaccines are considered acceptable.

cMinimum acceptable interval since previous dose in the series. Doses given within 4 days before the minimum interval are considered acceptable.

dDiphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular or whole-cell pertussis vaccine.

eIn most cases, 4 doses of Hib are recommended; however, the 6-month dose is not needed if haemophilus b conjugate (PRP-OMP) (PedvaxHIB or ComVax [Merck]) is used for the 2- and 4-month doses.

In addition to receipt of vaccines as recommended, we evaluated a more lenient timeliness estimate that was based on minimum ages at which doses are considered valid and minimum acceptable intervals between doses of multidose vaccines (Table 1 ▶). The ACIP acknowledges that vaccines administered before the recommended ages, but after minimum acceptable ages, may not be optimal but will likely lead to adequate protection. To assist providers in determining whether doses administered early should be readministered, the ACIP defined a 4-day grace period before the specified minimum age or interval. Vaccinations administered during this grace period also are considered acceptable; those administered before this grace period should be repeated.1 For our analysis, children were considered to have been vaccinated with acceptable timeliness if they received all doses in the 4:3:1:3:3 series within 4 days before the minimum acceptable age through the routinely recommended age ranges.

Several additional measures are useful when describing timeliness of vaccinations. We examined the percentages of children in each state who received at least 1 vaccine dose after the recommended age range but before 24 months (late), had not received all recommended vaccines before 24 months of age (never), and had received at least 1 vaccine dose too early to be considered valid (i.e., more than 4 days before the minimum acceptable age or the minimum acceptable interval between doses) (invalid ).

Necessity of the 6-month dose of Hib depends on the manufacturer of the doses given at 2 and 4 months.13 Because the NIS does not collect manufacturer information, we made lenient assumptions regarding the need for the 6-month dose.5 Briefly, children who received 4 doses were assumed to be following the 4-dose schedule, and those who received fewer than 3 doses were assumed to be following the 3-dose schedule. An evaluation of children who received 3 doses was made on the basis of the timing of the third dose.

Statistical Analysis

Percentage estimates and associated standard errors were calculated with SUDAAN software, version 8.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC). For regional comparisons, multiple logistic regression was used to adjust for characteristics of the child, mother, and vaccination providers. For maps, states were grouped into quartiles on the basis of the point estimates of the percentage of children who received all vaccinations in the 4:3:1:3:3 series as recommended.

One of our goals was to enable each state to compare its results with other states. We used a modified Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons as described by Almond et al., which was developed to optimize comparisons between a reference state and all other states.14 A full Bonferroni adjustment allows comparisons between all 1275 pairs of states and thus produces extremely wide confidence bounds. However, from the point of view of any given state or the District of Columbia, only 50 comparisons are of interest. In our analysis, a reference state was fixed; comparisons were made between it and each of the other states and the District of Columbia. The reference state’s result is represented by a shaded bar, defined by

|

(1) |

and other states are represented by bars defined by

|

(2) |

where xref is the point estimate for the reference state, xi is the point estimate for state i, sref is the standard error for the reference state, and si is the standard error for state i (Figure 1 ▶). The constant 3.3 is the upper (1–0.025/50)th percentile of a standard normal distribution; this was chosen so that the probability of at least 1 Type I error among the 50 comparisons was, at most, 0.05. Details of this method have been published elsewhere.14

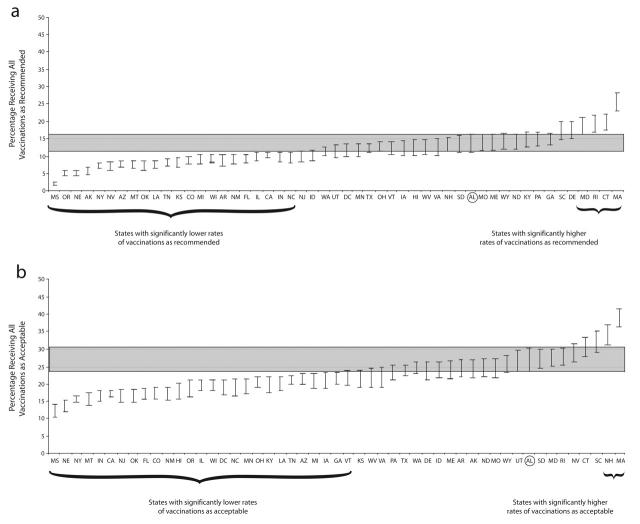

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of children in each state, with confidence intervals presented as error bars, receiving all vaccinations (a) as recommended and (b) as acceptable. Alabama was the reference state; its confidence bar is shaded across the graphs.

Note. Sample was US children aged 24–35 months in the 2000–2002 National Immunization Survey. Recommended vaccinations were 4 doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular or whole-cell pertussis vaccine, 3 doses of poliovirus vaccine, 1 dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, 3 or 4 doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, and 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine, per the guidelines of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Acceptable vaccinations were received from 4 days before the minimum acceptable age through the routinely recommended age.

For comparison states, the resulting bars are not confidence intervals and have no meaning alone. Indeed, the bars can only be interpreted in terms of comparing a given state’s unshaded bar with the reference state’s shaded bar. The bars (both shaded and unshaded) are defined so that a statistically significant difference between the reference state and any other state, at the α = 0.05 level, is achieved if the state’s unshaded bar does not overlap the reference state’s shaded bar. Because the equation used to calculate the bar width for the selected reference state differs from that used for the comparison states, and because the lengths of all the confidence bars are dependent on the standard error of the reference state, individualized analyses must be conducted for each reference state of interest. For illustrative purposes, we show Alabama (the first state in alphabetical order) as the reference state. A complete set of graphs, with each state as the reference, can be obtained from http://www.cdc.gov/nip or from the corresponding author.

RESULTS

The percentages of children who received all vaccinations as recommended varied widely by state, from only 2% in Mississippi to 26% in Massachusetts (Table 2 ▶). Antigen-specific timeliness also varied considerably by state. The percentages of children who were vaccinated as recommended were generally higher for antigen-specific series that required fewer doses than for those that required more doses. The percentages of children who received the single dose of MMR as recommended ranged from 64% in Montana to 84% in Hawaii, while receipt of all 4 doses of DTP as recommended ranged from only 17% in Mississippi to 43% in Massachusetts. The range for all Hib doses was 11% in Mississippi to 45% in Massachusetts, the range for all 3 poliovirus vaccine doses was 38% in Alaska to 58% in Rhode Island, and the range for all 3 Hepatitis B vaccine doses was 49% in Vermont to 82% in Rhode Island.

TABLE 2—

Estimated Percentages of Children Aged 24–35 Months Who Received Timely Vaccinations by State: National Immunization Survey, United States, 2000–2002.

| All Doses As Recommendeda | All Doses Acceptableb | At Least 1 Dose | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4 DTPc | 3 Poliod | MMRe | 3 HepBf | 3–4 Hibg | 4:3:1:3:3h | 4:3:1:3:3 | Latei | Never j | Invalidk | ||||||||||||

| State | Unweighted Sample Size | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE |

| Alabama | 1164 | 32.4 | (1.8) | 52.2 | (2.0) | 75.7 | (1.7) | 70.1 | (1.8) | 29.4 | (1.8) | 13.6 | (1.3) | 26.9 | (1.8) | 60.3 | (2.0) | 33.3 | (1.9) | 4.5 | (0.8) |

| Alaska | 581 | 17.0 | (1.7) | 38.2 | (2.2) | 67.1 | (2.1) | 66.7 | (2.1) | 18.0 | (1.6) | 5.9 | (1.0) | 24.1 | (1.9) | 60.8 | (2.2) | 39.2 | (2.2) | 8.4 | (1.2) |

| Arizona | 1238 | 20.4 | (1.3) | 44.5 | (1.6) | 72.5 | (1.5) | 64.5 | (1.6) | 19.8 | (1.3) | 7.9 | (0.9) | 21.2 | (1.3) | 59.9 | (1.6) | 46.7 | (1.6) | 13.0 | (1.0) |

| Arkansas | 693 | 18.3 | (1.7) | 49.5 | (2.2) | 74.8 | (1.9) | 69.2 | (2.0) | 25.5 | (2.0) | 8.7 | (1.2) | 24.2 | (1.8) | 60.8 | (2.1) | 43.8 | (2.2) | 6.0 | (1.0) |

| California | 2457 | 29.8 | (1.3) | 50.0 | (1.4) | 79.4 | (1.2) | 67.2 | (1.4) | 18.1 | (1.1) | 9.9 | (0.9) | 17.3 | (1.0) | 61.8 | (1.4) | 45.1 | (1.4) | 9.5 | (0.8) |

| Colorado | 683 | 26.4 | (1.8) | 50.9 | (2.1) | 71.8 | (1.9) | 61.9 | (2.1) | 21.4 | (1.7) | 8.7 | (1.1) | 17.4 | (1.5) | 56.3 | (2.1) | 53.0 | (2.1) | 13.0 | (1.4) |

| Connecticut | 614 | 38.3 | (2.1) | 50.3 | (2.2) | 80.3 | (1.8) | 64.1 | (2.2) | 31.6 | (2.0) | 19.7 | (1.7) | 30.7 | (2.0) | 62.5 | (2.1) | 24.8 | (2.0) | 7.3 | (1.1) |

| Delaware | 612 | 39.7 | (2.2) | 54.5 | (2.2) | 75.2 | (1.9) | 71.4 | (2.0) | 26.5 | (1.9) | 17.3 | (1.6) | 23.4 | (1.8) | 62.0 | (2.1) | 36.1 | (2.1) | 8.1 | (1.2) |

| DC | 577 | 27.8 | (2.0) | 41.3 | (2.4) | 69.6 | (2.4) | 62.3 | (2.4) | 21.6 | (1.9) | 11.4 | (1.3) | 18.3 | (1.7) | 71.0 | (2.1) | 41.9 | (2.5) | 13.8 | (1.9) |

| Florida | 1712 | 26.0 | (1.6) | 43.6 | (1.8) | 71.8 | (1.6) | 60.4 | (1.8) | 21.0 | (1.5) | 9.3 | (1.1) | 17.0 | (1.4) | 68.7 | (1.7) | 41.7 | (1.8) | 11.0 | (1.1) |

| Georgia | 1254 | 38.7 | (1.9) | 55.3 | (1.9) | 74.3 | (1.7) | 72.2 | (1.7) | 23.4 | (1.6) | 14.8 | (1.3) | 21.3 | (1.5) | 57.4 | (1.9) | 41.6 | (1.9) | 9.1 | (1.0) |

| Hawaii | 579 | 39.7 | (2.3) | 56.1 | (2.4) | 83.8 | (1.7) | 68.6 | (2.3) | 21.4 | (1.9) | 12.1 | (1.5) | 17.7 | (1.7) | 56.5 | (2.3) | 48.9 | (2.3) | 5.4 | (1.0) |

| Idaho | 682 | 20.0 | (1.6) | 46.2 | (2.0) | 64.9 | (2.0) | 66.9 | (1.9) | 24.5 | (1.7) | 10.3 | (1.2) | 23.9 | (1.7) | 59.1 | (2.0) | 35.5 | (2.0) | 10.0 | (1.2) |

| Illinois | 1258 | 31.4 | (1.6) | 45.3 | (1.7) | 73.4 | (1.6) | 65.6 | (1.7) | 19.3 | (1.3) | 9.6 | (1.0) | 19.0 | (1.4) | 64.8 | (1.6) | 42.9 | (1.7) | 8.6 | (0.9) |

| Indiana | 1151 | 27.1 | (1.7) | 43.5 | (1.9) | 65.3 | (1.9) | 67.0 | (1.9) | 15.2 | (1.3) | 9.7 | (1.1) | 16.5 | (1.3) | 65.9 | (1.8) | 43.7 | (1.9) | 10.7 | (1.2) |

| Iowa | 596 | 33.3 | (2.1) | 51.7 | (2.2) | 69.3 | (2.1) | 73.1 | (2.0) | 18.7 | (1.7) | 12.2 | (1.4) | 20.8 | (1.8) | 56.4 | (2.2) | 46.2 | (2.2) | 9.0 | (1.3) |

| Kansas | 588 | 21.0 | (1.8) | 48.9 | (2.4) | 73.7 | (2.1) | 66.5 | (2.3) | 24.7 | (2.1) | 8.2 | (1.1) | 21.5 | (1.8) | 58.6 | (2.3) | 45.0 | (2.4) | 10.8 | (1.4) |

| Kentucky | 629 | 34.7 | (2.1) | 53.5 | (2.3) | 68.3 | (2.1) | 69.4 | (2.2) | 21.8 | (1.8) | 14.7 | (1.5) | 19.8 | (1.7) | 61.7 | (2.2) | 40.9 | (2.2) | 9.2 | (1.5) |

| Louisiana | 1191 | 20.2 | (1.6) | 46.3 | (2.0) | 67.8 | (1.9) | 67.2 | (1.9) | 23.4 | (1.7) | 7.4 | (1.1) | 19.9 | (1.6) | 62.7 | (2.0) | 45.0 | (2.1) | 10.4 | (1.3) |

| Maine | 608 | 38.2 | (2.1) | 57.0 | (2.2) | 75.2 | (2.0) | 68.8 | (2.0) | 26.0 | (1.9) | 13.9 | (1.5) | 23.9 | (1.8) | 52.7 | (2.2) | 45.7 | (2.2) | 7.5 | (1.2) |

| Maryland | 1197 | 40.4 | (2.0) | 56.9 | (2.0) | 77.9 | (1.7) | 67.2 | (2.0) | 34.1 | (1.9) | 18.5 | (1.5) | 27.3 | (1.8) | 59.7 | (2.0) | 33.6 | (1.9) | 8.8 | (1.1) |

| Massachusetts | 1235 | 42.6 | (1.9) | 55.7 | (1.9) | 80.7 | (1.6) | 71.1 | (1.8) | 44.6 | (1.9) | 25.5 | (1.7) | 39.0 | (1.9) | 50.3 | (2.0) | 23.5 | (1.7) | 4.9 | (0.8) |

| Michigan | 1187 | 23.1 | (1.6) | 46.4 | (2.0) | 71.7 | (1.8) | 64.9 | (1.9) | 21.9 | (1.6) | 9.0 | (1.1) | 20.8 | (1.6) | 65.2 | (1.9) | 38.6 | (2.0) | 8.2 | (1.1) |

| Minnesota | 638 | 37.2 | (2.1) | 55.5 | (2.2) | 73.5 | (2.0) | 73.1 | (2.0) | 20.7 | (1.7) | 11.0 | (1.3) | 18.7 | (1.6) | 51.5 | (2.2) | 55.0 | (2.2) | 8.8 | (1.3) |

| Mississippi | 581 | 16.5 | (1.7) | 45.7 | (2.4) | 69.4 | (2.3) | 66.8 | (2.3) | 11.0 | (1.5) | 1.9 | (0.6) | 12.1 | (1.5) | 58.6 | (2.3) | 65.1 | (2.3) | 8.8 | (1.3) |

| Missouri | 566 | 30.0 | (2.1) | 45.2 | (2.3) | 77.0 | (2.0) | 67.5 | (2.2) | 23.8 | (1.9) | 13.6 | (1.5) | 24.1 | (1.9) | 59.7 | (2.2) | 38.3 | (2.3) | 6.7 | (1.3) |

| Montana | 629 | 27.8 | (1.9) | 46.9 | (2.2) | 63.7 | (2.3) | 68.1 | (2.2) | 15.4 | (1.5) | 7.4 | (1.1) | 15.6 | (1.5) | 58.1 | (2.2) | 53.8 | (2.3) | 9.6 | (1.3) |

| Nebraska | 626 | 28.9 | (2.0) | 48.4 | (2.2) | 70.7 | (2.0) | 71.6 | (2.0) | 12.0 | (1.4) | 4.9 | (0.9) | 13.3 | (1.4) | 50.6 | (2.2) | 60.8 | (2.1) | 7.2 | (1.1) |

| Nevada | 620 | 18.2 | (1.7) | 45.3 | (2.2) | 70.7 | (2.1) | 64.8 | (2.1) | 27.0 | (1.9) | 6.9 | (1.1) | 28.2 | (1.9) | 55.9 | (2.2) | 36.9 | (2.2) | 8.8 | (1.3) |

| New Hampshire | 658 | 31.8 | (2.0) | 52.3 | (2.2) | 80.7 | (1.7) | 69.4 | (2.0) | 29.2 | (1.9) | 13.3 | (1.4) | 34.0 | (2.0) | 53.7 | (2.1) | 27.8 | (1.9) | 5.3 | (1.0) |

| New Jersey | 1252 | 29.9 | (1.9) | 42.0 | (2.1) | 68.3 | (2.0) | 59.7 | (2.1) | 22.1 | (1.7) | 9.7 | (1.2) | 16.3 | (1.5) | 73.4 | (1.8) | 36.1 | (2.1) | 9.4 | (1.4) |

| New Mexico | 636 | 26.1 | (1.9) | 45.9 | (2.2) | 75.0 | (2.0) | 62.5 | (2.2) | 18.5 | (1.7) | 9.1 | (1.2) | 17.0 | (1.6) | 60.2 | (2.2) | 52.5 | (2.2) | 12.1 | (1.6) |

| New York | 1175 | 27.5 | (1.4) | 39.4 | (1.6) | 75.8 | (1.5) | 64.8 | (1.6) | 16.4 | (1.2) | 7.3 | (0.8) | 15.5 | (1.1) | 67.4 | (1.5) | 44.5 | (1.7) | 10.3 | (1.0) |

| North Carolina | 601 | 33.9 | (2.2) | 56.3 | (2.4) | 83.7 | (1.8) | 66.4 | (2.3) | 19.7 | (1.8) | 9.4 | (1.2) | 18.7 | (1.7) | 57.6 | (2.3) | 51.0 | (2.4) | 4.9 | (0.9) |

| North Dakota | 662 | 33.8 | (2.0) | 51.1 | (2.2) | 67.0 | (2.1) | 71.1 | (2.1) | 23.0 | (1.7) | 14.2 | (1.4) | 24.4 | (1.8) | 54.3 | (2.2) | 41.2 | (2.2) | 6.8 | (1.0) |

| Ohio | 1861 | 27.9 | (1.5) | 43.6 | (1.7) | 70.0 | (1.6) | 64.9 | (1.6) | 22.8 | (1.4) | 12.5 | (1.1) | 20.5 | (1.3) | 65.5 | (1.6) | 41.8 | (1.7) | 8.2 | (0.9) |

| Oklahoma | 619 | 26.8 | (2.0) | 42.9 | (2.2) | 69.8 | (2.1) | 58.1 | (2.3) | 16.9 | (1.6) | 7.4 | (1.2) | 16.5 | (1.6) | 63.2 | (2.1) | 51.1 | (2.3) | 13.3 | (1.5) |

| Oregon | 615 | 22.0 | (1.7) | 43.4 | (2.2) | 67.5 | (2.1) | 63.6 | (2.1) | 19.0 | (1.7) | 4.9 | (0.9) | 18.6 | (1.7) | 63.4 | (2.1) | 41.1 | (2.2) | 10.9 | (1.4) |

| Pennsylvania | 1133 | 36.6 | (1.9) | 48.6 | (2.0) | 73.7 | (1.8) | 72.6 | (1.8) | 23.7 | (1.7) | 14.5 | (1.4) | 23.0 | (1.7) | 62.1 | (1.9) | 40.5 | (2.0) | 6.7 | (0.9) |

| Rhode Island | 689 | 40.5 | (2.0) | 57.6 | (2.1) | 81.5 | (1.6) | 81.6 | (1.6) | 29.3 | (1.8) | 19.2 | (1.5) | 27.4 | (1.8) | 50.6 | (2.1) | 41.5 | (2.1) | 7.9 | (1.0) |

| South Carolina | 613 | 32.3 | (2.1) | 56.2 | (2.2) | 76.3 | (2.0) | 71.3 | (2.1) | 35.5 | (2.1) | 17.2 | (1.6) | 32.2 | (2.1) | 57.3 | (2.2) | 28.2 | (2.1) | 5.3 | (0.9) |

| South Dakota | 588 | 26.8 | (2.0) | 44.3 | (2.3) | 66.4 | (2.2) | 65.2 | (2.3) | 22.1 | (1.8) | 13.4 | (1.5) | 27.1 | (2.0) | 61.3 | (2.2) | 29.3 | (2.2) | 7.0 | (1.3) |

| Tennessee | 1827 | 25.3 | (1.5) | 49.5 | (1.7) | 72.1 | (1.5) | 66.0 | (1.6) | 21.7 | (1.4) | 7.9 | (0.9) | 21.0 | (1.4) | 58.3 | (1.7) | 41.8 | (1.7) | 8.9 | (1.0) |

| Texas | 3160 | 25.6 | (1.4) | 51.3 | (1.6) | 74.1 | (1.5) | 64.2 | (1.5) | 27.1 | (1.4) | 12.3 | (1.1) | 23.9 | (1.3) | 58.3 | (1.6) | 43.4 | (1.6) | 8.4 | (0.8) |

| Utah | 616 | 25.2 | (1.9) | 50.2 | (2.2) | 78.1 | (1.8) | 65.7 | (2.1) | 24.6 | (1.9) | 11.2 | (1.4) | 26.7 | (2.0) | 54.6 | (2.2) | 41.1 | (2.2) | 8.0 | (1.2) |

| Vermont | 670 | 38.7 | (2.0) | 57.3 | (2.1) | 80.2 | (1.7) | 49.4 | (2.1) | 34.9 | (2.0) | 12.1 | (1.3) | 21.6 | (1.7) | 70.1 | (1.9) | 28.0 | (1.9) | 5.9 | (1.0) |

| Virginia | 545 | 33.2 | (2.3) | 47.2 | (2.4) | 68.0 | (2.3) | 65.6 | (2.3) | 23.2 | (2.0) | 12.6 | (1.6) | 21.9 | (2.0) | 60.0 | (2.4) | 41.5 | (2.4) | 7.5 | (1.2) |

| Washington | 1212 | 27.6 | (1.5) | 49.4 | (1.7) | 72.2 | (1.5) | 63.8 | (1.6) | 27.3 | (1.5) | 11.2 | (1.0) | 24.4 | (1.4) | 55.9 | (1.7) | 42.7 | (1.7) | 8.0 | (0.9) |

| West Virginia | 574 | 31.9 | (2.2) | 51.4 | (2.3) | 74.5 | (2.0) | 62.4 | (2.2) | 29.0 | (2.1) | 12.4 | (1.5) | 21.2 | (1.8) | 64.0 | (2.2) | 32.6 | (2.2) | 6.3 | (1.1) |

| Wisconsin | 1189 | 28.6 | (1.6) | 47.6 | (1.8) | 74.1 | (1.5) | 66.5 | (1.7) | 21.1 | (1.4) | 9.0 | (1.0) | 19.2 | (1.4) | 60.9 | (1.7) | 44.7 | (1.8) | 8.6 | (0.9) |

| Wyoming | 631 | 30.3 | (2.0) | 49.5 | (2.2) | 70.1 | (2.0) | 63.4 | (2.2) | 26.8 | (1.9) | 14.1 | (1.5) | 25.5 | (1.8) | 59.3 | (2.2) | 32.3 | (2.1) | 8.7 | (1.2) |

| Total | 47 672 | 29.3 | (0.3) | 48.3 | (0.4) | 74.1 | (0.3) | 66.2 | (0.4) | 22.4 | (0.3) | 11.0 | (0.2) | 20.7 | (0.3) | 61.5 | (0.4) | 42.5 | (0.4) | 8.8 | (0.2) |

aRecommended age for routine administration approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

b Within 4 days before the minimum acceptable age through the routinely recommended age.

c4 doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular or whole-cell pertussis vaccine.

d3 doses of poliovirus vaccine.

e1 dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine.

f 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine.

g3–4 doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, as appropriate.

h4 doses of DTP, 3 doses of poliovirus vaccine, 1 dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, 3 doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, and 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine.

i Children received at least 1 vaccine dose after the recommended age range but before 24 months of age.

j Children had not received all recommended vaccines before 24 months of age.

kChildren received at least 1 vaccine dose too early to be considered valid (i.e., more than 4 days before the minimum acceptable age or the minimum acceptable interval between doses of multi-dose vaccines).

The more lenient definition of acceptable timeliness for the 4:3:1:3:3 series produced higher estimates, with a range of 12% in Mississippi to 39% in Massachusetts (Table 2 ▶). There was considerable variation among states in the percentages of children who received at least 1 vaccine dose late but before 24 months of age (50% in Massachusetts to 73% in New Jersey). The percentages of children who were missing at least 1 dose in the 4:3:1:3:3 series at 24 months of age (i.e., children who were not completely vaccinated by 24 months) ranged from 24% in Massachusetts to 65% in Mississippi. Finally, the percentages of children who received at least 1 invalidly early dose ranged from 5% in Alabama to 14% in the District of Columbia.

State-specific receipt of the 4:3:1:3:3 series of vaccinations as recommended and as acceptable is shown in Figure 1 ▶. Because the difference in measurement standards had more effect on some states than others, the order of states is different in the 2 graphs. Alabama is the reference state, and its confidence bar is shaded across the graphs. Those states on the left with confidence bars that do not overlap Alabama’s have statistically significantly lower rates of children who received all vaccinations as recommended (22 states) or considered to be acceptable (26 states). Similarly, those states on the right with confidence bars that do not overlap Alabama’s have statistically higher rates of children who received all vaccinations as recommended (4 states) or considered to be acceptable (2 states). The states whose confidence bars overlap the shaded area (24 states for receipt as recommended, 22 states for receipt considered to be acceptable) were not statistically different from Alabama at the α = 0.05 level. These graphs are appropriate only for comparing Alabama with another state or states; comparisons between other pairs of states require individualized graphs, with the state of interest as the reference state.

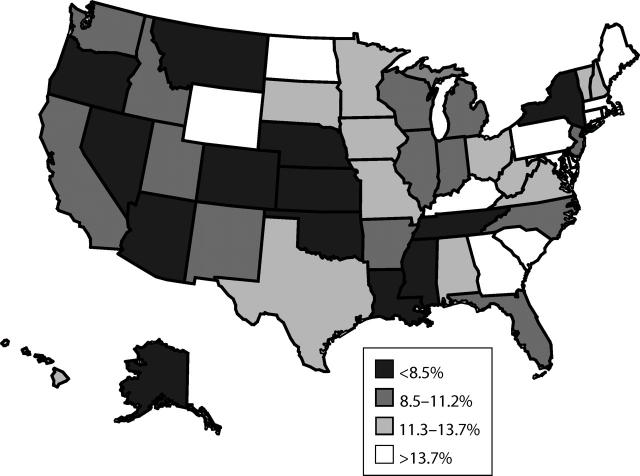

Census region estimates of timeliness were lower in the western (10%) and midwestern (10%) regions than in the northeastern (13%) and southern (12%) regions. After we controlled for demographic factors (race/ethnicity of the child; household poverty status, number of children, and Metropolitan Statistical Area status; mother’s marital status, age, and educational level; and number and type of vaccination providers), the western region still had significantly lower vaccination timeliness than the northeastern region (OR = 0.8; P< .001). Maps of state-specific timeliness estimates show that, with some exceptions, western states tended to have lower rates of children who received all vaccinations as recommended than did eastern states (Figure 2 ▶). In fact, 9 of the 19 states in the western half of the country were in the lowest quartile compared with 4 of the 32 states in the eastern half, and only 2 of the 19 western states were in the highest quartile compared with 10 of the 32 eastern states.

FIGURE 2—

States by quartiles of percentage of children receiving all vaccinations as recommended.

Note. Sample was US children aged 24–35 months in the 2000–2002 National Immunization Survey. Recommended vaccinations were 4 doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular or whole-cell pertussis vaccine, 3 doses of poliovirus vaccine, 1 dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, 3 or 4 doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, and 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine, per the guidelines of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

DISCUSSION

Public health program administrators and vaccination providers must give greater priority to ensuring children receive all vaccinations as recommended. In addition to traditional vaccination coverage estimates and disease surveillance, providers of vaccination programs can monitor timeliness of vaccination to ensure that children remain fully vaccinated and optimally protected at all times throughout early childhood. Such multifaceted examination of immunization administration is more sensitive to the nature of underimmunization than simple assessment of the number of doses accumulated by age 19 to 35 months.

We found that state-specific rates for timeliness of the 4:3:1:3:3 series were as low as 2% for receipt of all vaccinations as recommended and only 12% when acceptable early vaccinations were included. Even in the most timely states, 74% (recommended) and 61% (acceptable) of children had at least 1 inappropriately timed vaccination. These results confirm that much work remains for state vaccination programs to promote the vaccination of children in accordance with published national recommendations.

Public Health Importance

State-specific vaccination coverage rates published annually by the CDC usually focus on the number of vaccinations administered by a given age rather than whether vaccinations were given at the recommended times. Risk of disease because of a delay in vaccine administration varies and depends on the vaccine, disease circulation, transmissibility, likelihood of importation, and severity of outcome. Although vaccine-preventable disease incidence is generally low in the United States,15 vaccination timeliness is important for several reasons. First, inappropriately timed vaccinations may be less effective. The safety and efficacy of early and late vaccination have been evaluated for some vaccines but are not known in all cases and may vary by dose. Second, timely vaccinations protect children as early as possible and prevent disease outbreaks. This is particularly important for diseases that are continuously circulating, such as pertussis, and for diseases that have the potential to cause large outbreaks, such as measles. Third, delayed or inappropriately timed vaccinations have administrative, programmatic, and cost implications. Doses that are given too early to be considered valid must be repeated, which results in unnecessary risk for adverse reaction and increased costs. We found that in some states as many as 14% of children received an invalid dose. Administratively, assessing vaccination status during health care visits becomes increasingly complex when children have fallen behind schedule or have received invalid doses.

The information on antigen-specific timeliness presented in our article will allow states to determine the level of susceptibility for specific diseases of interest and pinpoint weaknesses in their vaccination programs. For example, although Vermont and North Dakota had relatively high levels of timeliness for the 4:3:1:3:3 series, Vermont had low timeliness for the 3-dose Hepatitis B vaccine series, and North Dakota had low timeliness for the MMR vaccine. Such information at state levels is particularly important because outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases are likely to affect geographical clusters of susceptible individuals.

Appropriate Use of State-Specific Information

State monitoring of early childhood vaccination is a long-standing component of protecting public health. Localized low coverage and important differences between states can be obscured by high national coverage. Because vaccine-preventable diseases tend to cluster geographically, state-specific vaccination information offers a better opportunity for preventing outbreaks than national results do. Additionally, many vaccination activities and policies are implemented at the state level.

Comparing a state’s vaccination timeliness with that of other states may facilitate more productive policy decisions and interventions, because the need for an intervention and model vaccination programs can be more reliably defined. However, simply assessing the rank order of point estimates may obscure the fact that several programs are performing at approximately the same high or low levels. The uncertainty associated with a state’s rank must be accounted for, just as the uncertainty of a point estimate is quantified by a confidence interval.16 Our figures allow appropriate determination of a range for the reference state’s rank. For example, although Alabama’s point estimate for timely vaccination was the 14th highest among all states, it did not differ statistically from the 15 states below it and the 9 states above it; confidence bars for all 24 of these states fell within the shaded bar. Thus, we can say with 95% confidence that Alabama’s rank for timely vaccination coverage was between 5th and 29th.

Moreover, examining a rank order list for overlap of confidence intervals may lead to mistaken conclusions about differences among states because of 2 factors: (1) when 2 confidence intervals overlap, the difference may or may not be significant,17 and (2) when comparing each state with the other states and the District of Columbia, simply constructing 50 95% confidence intervals does not account for the many comparisons that can be made. Even when there are no differences between states, naïve use of 95% confidence intervals will likely result in 2 or 3 apparent differences between the state of interest and the other states. These 2 factors have opposite effects: the first will lead to too few states being identified as different from the state of interest, and the latter will lead to identification of too many states. The combined direction of bias depends on the circumstances. In our analysis, a naïve direct comparison of confidence intervals would have been more conservative, leading to the identification of 13 states with lower percentages and 3 states with higher percentages of children who received all vaccinations as recommended compared with 22 lower percentages and 4 higher percentages in our analysis. The method we used is more complicated than traditional confidence intervals, but it allows appropriate comparison of a reference state with all other states by properly adjusting for the multiple comparisons being made.

Conclusions

Ensuring timely vaccinations requires a proactive approach to vaccination interventions. For example, reminder/recall systems are highly effective for improving vaccination coverage.18 To encourage timeliness, focusing on the “reminder” component (contacting clients to remind them of upcoming vaccinations or already scheduled visits to receive vaccinations), would be more beneficial than focusing on “recall” (contacting patients after they have fallen behind). Additionally, physicians must stress the importance of timely vaccination, make every effort to ensure that vaccination visits are scheduled at appropriate ages, and fully utilize every opportunity for vaccination. States can use the information about vaccination timeliness presented here, along with other routine vaccination measures, to (1) more fully understand and monitor the strengths and weaknesses of their vaccination programs, (2) prioritize needs, and (3) develop appropriate public health strategies.

Acknowledgments

This research and the National Immunization Survey were conducted through funding and approval by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services (grant 200-1999-07001).

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors E. T. Luman originated the study, completed the analyses, and led the writing. L. E. Barker provided statistical and epidemiological consultation and supervision. All the authors originated ideas, interpreted findings, and reviewed drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National, state, and urban area vaccination coverage levels among children aged 19–35 months—United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50: 637–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker L, Luman E, Zhao Z, et al. National, state, and urban area vaccination coverage levels among children aged 19–35 months—United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:664–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker L, Darling N, McCauley M, Santoli J. National, state, and urban area vaccination coverage levels among children aged 19–35 months—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003; 52:728–732.12904739 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luman ET, McCauley MM, Stokley S, Chu SY, Pickering LK. Timeliness of childhood immunizations. Pediatrics. 2002;110:935–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith PJ, Battaglia MP, Huggins VJ, et al. Overview of the sampling design and statistical methods used in the National Immunization Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(suppl 4):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zell E, Ezzati-Rice TM, Battaglia M, Wright R. National Immunization Survey: the methodology of a vaccination surveillance system. Public Health Rep. 2000; 115:65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankel MR, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC, et al. Adjustments for non-telephone bias in random-digit-dialling surveys. Stat Med. 2003;22:1611–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith PJ, Rao JNK, Battaglia MP, Barker LE, Khare M. Methodology of the National Immunization Survey: 1994–2002. Vital and Health Stat 2. 2005; Mar(138):1–55. [PubMed]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedule—United States, July–December 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:Q1–Q4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53: 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: recommended childhood immunization schedule—United States, 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almond RG, Lewis C, Tukey JW, Yan D. Displays for comparing a given state to many others. Am Statistician. 2000;54:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: final 2003 reports of notifiable diseases. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53: 687–696. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker LE, Smith PJ, Gerzoff RB, Luman ET, McCauley MM, Strine TW. Ranking states’ immunization coverage: an example from the National Immunization Survey. Stat Med. 2005;24:605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schenker N, Gentleman JF. On judging the significance of differences by examining the overlap between confidence intervals. Am Statistician. 2001;55: 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szilagyi P, Bordley C, Chelminski A, Kraus R, Margolis P, Rodewald L. Interventions aimed at improving immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD003941. [DOI] [PubMed]