Abstract

The evolution of international health has typically been assessed from the standpoint of central institutions (international health organizations, foundations, and development agencies) or of one-way diffusion and influence from developed to developing countries.

To deepen understanding of how the international health agenda is shaped, I examined the little-known case of Uruguay and its pioneering role in advancing and institutionalizing child health as an international priority between 1890 and 1950.

The emergence of Uruguay as a node of international health may be explained through the country’s early gauging of its public health progress, its borrowing and adaptation of methods developed overseas, and its broadcasting of its own innovations and shortcomings.

THE HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL health has typically been examined from the perspective of metropolitan institutions such as the World Health Organization, the International Red Cross, and the Rockefeller Foundation.1–5 While some works trace the interactions of these agencies with far-flung actors, the motives, ideas, and operations of international health are invariably portrayed as centrally determined, then diffused around the world. To broaden this account of the development of the international health agenda, I examine the little-known case of Uruguay and its pioneering role in advancing child health as an international priority between 1890 and 1940.

Uruguay became involved in international health at least in part to search for solutions to its intractable infant mortality problem, and it ended up offering local approaches—including a children’s code of rights—that had global appeal. As the home of the International American Institute for the Protection of Childhood (Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia, or IIPI), the first permanent organization of its kind, founded in 1927, Montevideo became a node of international health which—though lacking the political cachet of Washington, DC, or Geneva, Switzerland—helped shape a worldwide children’s health agenda.

The transformation of Uruguay’s domestic debates into an influential institute can be observed through the international networks of Uruguayan doctors and child health advocates, the opportunities and interests that gave rise to the IIPI, and its repercussions, including Uruguay’s Children’s Code. My analysis, unlike a conventional history, highlights the emergence of a significant initiative from a peripheral location through the interplay of local political and social conditions with widely shared health priorities.

THE URUGUAYAN WAY

Despite its small size and its distance from the centers of power, Uruguay became engaged with international health developments beginning in the late 19th century. Founded in 1830 following a longstanding conflict between Spain/Argentina and Portugal/Brazil over possession of its territory, Uruguay enjoyed relative stability and a cattle-based economy after its civil wars subsided in 1851. Its high levels of urbanization and school attendance, tiny indigenous population, secular government, uniform and accessible geography, and mild, Mediterranean-like climate differentiated Uruguay from most of its neighbors. The country was peopled largely by Spanish and Italian immigrants, with a small elite of French ancestry and a few descendants of African slaves. Uruguay’s approximately 1 million residents (one third of whom lived in the capital, according to the1908 census)6 shared a self-effacing longing for Europe while developing their own brand of state protectionism.

Uruguay differed from most Latin American countries in that the Catholic Church and the landed elites were relatively weak forces as the modern state began to take shape in the late 19th century. Moreover, the country’s sparse institutional infrastructure in the social arena left room for state growth.7,8 The rapid expansion of public education for both sexes that started in the 1870s—making Uruguay the region’s leader in literacy, with 54% literacy in 19009—presaged the welfare state, which emerged in full force under the reformist Colorado Party administrations of President José Batlle y Ordóñez (1903–1907 and 1911–1915). Enabled by relative prosperity and the sidelining of the opposition Blanco Party, Batlle’s first administration opened a wide-ranging dialogue on issues such as universal suffrage, maternal benefits, and working conditions. Concretely, it established retirement and other benefits for the civil service.10

A severe economic crisis in 1913 accelerated the implementation of various Batllista policies—including an 8-hour workday and exemption from taxes on essential goods—that seemed to prefigure Keynesian approaches to mitigating the social and economic inequalities provoked by capitalism. Indeed, Batlle conceived of a protective state that offered compensation for injustices suffered by various segments of the population. His ambitious agenda of centralization and redistribution included old-age pensions, worker protections, state monopoly of finance and other sectors, and public assistance for women, children, and the poor.11,12 That progress in enacting reforms was slow—in part because the reforms yielded contradictory results, such as lower wages13–15—did not cause the country to be viewed as a failed experiment. Instead this stepwise approach elicited attention: a variety of voices engaged in decades of lively debate, domestically and internationally, over the effectiveness of the Batllista state and of its particular features, such as those improving child health and welfare.

Uruguay’s place in the globalizing health system was at once peculiar and typical. Like Central and Eastern European countries at the time, Uruguay shared many of the modern state-building and cultural values of Western Europe but had a still largely rural economy. Like other Latin American countries, Uruguay was not tied to a single international mandate, instead interacting with a changing panorama of public health examples.

Mid–19th-century European concerns with preventing the spread of epidemic diseases—and the economic consequences of the resulting trade interruptions—were echoed in a series of meetings held in Montevideo and Rio de Janeiro starting in 1873 aimed at standardizing quarantine measures and maritime sanitation. The meat- and hide-exporting economies of Argentina and Uruguay were particularly intent on guarding against yellow fever from Brazil, since most ships entering the Río de la Plata after leaving Brazil stopped in both Buenos Aires and Montevideo. The 1887 sanitary convention signed by Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay—the first of its kind to be ratified in the Americas—detailed quarantine periods for ships bearing cholera, yellow fever, and plague and was in effect for 5 years before it broke apart. A 1904 successor convention included reciprocal notification. These treaties presaged pan-American efforts to prevent infectious outbreaks originating from immigrant and commercial vessels.16

GAUGING INFANT MORTALITY

In the late 19th century, Uruguay began to consider social policy an important underpinning of public health. Initially it was French legislation—maternity leave, welfare provisions, mandatory breastfeeding for abandoned infants, milk hygiene, and other puericultural (from Adolphe Pinard’s notion of the scientific cultivaiton of childhood and the improvement of child health and welfare through better conditions of childrearing) measures—that was most influential. In the 1930s many Uruguayan social policy-makers and doctors admired the Soviet health system. By the 1950s, Uruguayan public health was increasingly influenced by the technical and biomedical approach of the United States. Uruguay was never “passively derivative”17 of these models, instead selecting features from abroad and melding them with the ideas, reality, and politics at home.

A particular mark of Uruguay’s early participation in international health discussions was the founding of the Civil Registry in 1879, mandating the regular collection of birth and death records. Most of the nations that developed comprehensive vital statistics systems before 1900 were major powers concerned with population health as a sign of economic vitality. Rapidly industrializing England, France, and Germany, for example, monitored the survival of children as an indicator of workforce and military readiness and imperial strength.18,19 Though it had little industry and no pretense to empire-building, Uruguay had plenty of livestock to count: its first statistical annual, published for the 1873 World Exhibition in Vienna, was sponsored by the Uruguayan Agricultural Association.20

The European connections of the Uruguayan elites also propelled data collection. The country’s statistical annuals were self-consciously modeled after Parisian volumes,21 second half of the 19th century: more than 40 medical periodicals were founded, numerous hospitals and clinics were organized, and the country’s first friendly society (providing mutual aid for unemployment and medical care) was established in 1854. The University of the Republic’s Faculty of Medicine was founded in 1875, and by the time its state-of-the-art research facility was built in 1911, there were several dozen graduates per year.22,23

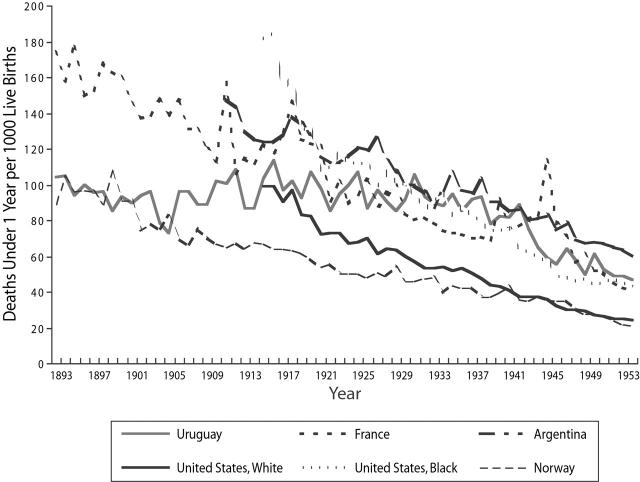

Statistical annuals compiling cause-specific mortality data were first published in 1885,24 with infant deaths added in 1893. This allowed health experts to follow the country’s uneven but sure decline in infant mortality from 104 deaths per 1000 live births in 1893 to 72 per 1000 in 1905. Over the next 35 years infant mortality stagnated, fluctuating between 85 and 113 deaths and averaging 95 deaths per 1000 live births. Only after 1940 did infant mortality resume its decline. Although other countries reported higher levels of infant mortality than Uruguay at particular points in time, virtually every other setting experienced continuous—if sometimes bumpy—declines25–27 (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

International comparisons of infant mortality rate,1893–1953.

Uruguay was thus unusual on several counts: in establishing a functioning civil registry early on, in achieving lower infant mortality rates than several European countries, and in experiencing a prolonged stagnation in infant mortality rates. The country’s early successes and its subsequent setbacks with infant mortality impelled health experts to identify the underpinnings of local circumstances and to search for international approaches that might prove helpful.

URUGUAYAN PUBLIC HEALTH ABROAD AND AT HOME

In 1895, approximately a decade after Uruguay’s civil registry achieved regular coverage, public health powers were consolidated under the National Council of Hygiene. Uruguay now had information, centralized authority, and a cadre of medical and public health experts keen to participate in international health developments. This group of experts documented Uruguayan health and mortality domestically and comparatively; advised policymakers; ran health and welfare institutions; saw patients in clinical settings; and participated in international congresses, publications, and other scientific activities.28,29

An early member of this group was Joaquin de Salterain (1856–1926), whose career illustrates the back-and-forth between international and Uruguayan developments in health. Of French and Spanish parentage, de Salterain was among the first graduates of Uruguay’s Faculty of Medicine in 1884 and won a government scholarship to go to Paris for specialized training in ophthalmology. Rather than narrowing his focus, his fellowship widened it, and on his return to Uruguay he became involved in a range of health activities. De Salterain was a constituting member of the National Council of Hygiene, and in the mid-1890s he began to publish detailed analyses of Montevideo’s mortality statistics.30,31 De Salterain headed Montevideo’s Department of Public Health and was a program director in the Pereira Rossell Children’s Hospital (founded in 1905) and the Dámaso Larrañaga children’s asylum (established in 1818). His work helped set the stage for Uruguay’s role abroad, but he was perhaps most effective at using his international interchanges to leverage increased attention and resources at home.

From the 1890s on, Uruguayans participated in virtually every international congress related to public health and social welfare. They published their own presentations in either Uruguayan or international journals and typically issued analytic summaries of the conference discussions in Uruguay’s Boletín del Consejo Nacional de Higiene (Bulletin of the National Council of Hygiene). Medical elites from throughout the Americas received advanced training in Europe during this period, making contacts, attending congresses, joining scientific networks, and pressing their own governments to expand activities. But few countries, particularly small countries, achieved as consistent an international presence as did Uruguay. Most countries sent 1 representative to the 1900 Paris conference at which the International Classification of Diseases was first revised; Uruguay sent 2.32 Similarly, the 7-person delegation Uruguay sent to Washington, DC, for the 15th International Congress on Hygiene and Demography in 1912 was larger than that of all but a handful of countries.33 That this attendance was at state expense—at a time when the National Council of Hygiene relied on a largely volunteer labor force—implies that politicians and bureaucrats believed Uruguay’s health learning would take place internationally.

Uruguay’s reorganization and expansion of social welfare fit with this notion of selectively adapting foreign developments. In 1907 Uruguay was among the first countries outside Europe and its colonies to found a milk station (gota de leche) based on the French model (goutte de lait) to distribute pasteurized milk and provide medical attention to needy mothers and their infants.34 By 1927, 33 milk stations had been established throughout the country, arguably covering the largest proportion of mothers and infants in the world. This number was exceeded only in France.

The 1910 nationalization of Uruguay’s charity institutions into the Asistencia Pública Nacional was likewise self-consciously patterned on France’s Assistance Publique, then expanded into one of the most far-reaching social assistance programs in the world.35 Uruguay also maintained Anglo-America–style private aid agencies (typically run by women), some of which received government grants to deliver services.36–38 The full legalization of divorce (including divorce unilaterally initiated by women) in 191339—giving the country one of the world’s most liberal divorce laws—was further evidence of Uruguay’s “borrow and change” social policy approach.

THINKING COMPARATIVELY, CONTRIBUTING INTERNATIONALLY

Uruguayans were clearly adept at participating in international health networks and adapting foreign innovations to serve local needs. Equally striking is how Uruguay’s self-publicized problems catapulted the country to regional and international attention.

In the late 19th century European countries began to conduct mortality comparisons, a practice Uruguay fully adopted. De Salterain observed in 1896 that Uruguay’s mortality rate was dropping steadily and that Montevideo’s rate was lower than those of Paris, London, St Petersburg, and Buenos Aires. De Salterain boasted, “What other explanation could there be for such pleasing results than the progress of our public welfare institutions, health administration, and hygiene education?”40

Other colleagues followed suit, especially after the infant mortality rate emerged as an international indicator around 1900.41 In 1913, Julio Bauzá, the doctor heading Montevideo’s milk stations, went so far as to argue that little attention needed to be paid to infant mortality because Uruguay’s rates were so much lower than those of Chile, France, Russia, and Germany. He affirmed, “The truth is we are in an enviable position for a myriad of European and American countries.”42

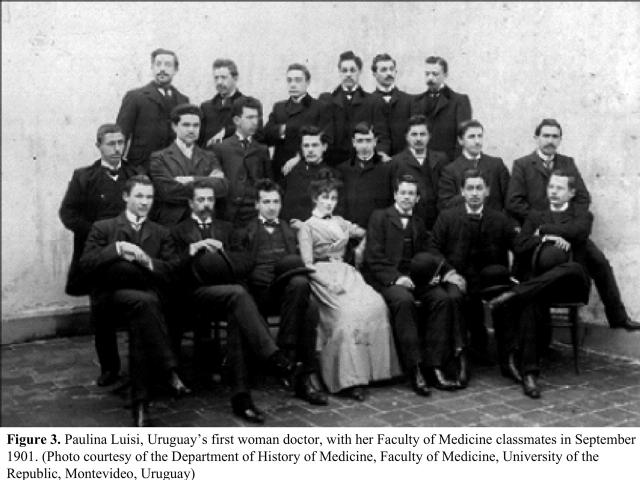

These early comparative analyses were aimed mostly at domestic audiences, but local experts soon recognized that Uruguay’s well-documented mortality patterns had relevance far beyond the country’s borders. Luis Morquio (1867–1935), the founding father of Uruguayan pediatrics and a leading authority on both medical and social aspects of child health, was the most prominent translator of the local experience to the international scene. In 1895, upon returning to Montevideo from training in Paris, he became medical director of the external services of the Orphanage and Foundling Home. There he oversaw an extraordinarily low—for the time—mortality rate of 7% of children, which he attributed to careful attention to infant feeding, including weekly visits to his clinic by wet-nurses and their charges.43,44

Morquio was presenting his analyses of Uruguay’s experience to Latin American medical congresses by 1904 and to European audiences soon after. If Morquio agreed that Uruguay’s infant mortality rates—rates favored, he believed, by environmental cleanliness, low population density, and high levels of breastfeeding45—deserved some international appreciation, he did not dwell on success, arguing that half of the infant deaths were avoidable46 (Figure 2 ▶).

FIGURE 2—

Stamp commemorating the 100 years since Dr. Luis Morquio became the Chair of Pediatrics at the Faculty of Medicine at Uruguay’s University of the Republic. Bottom right corner includes the statue of Morquio with a child that stands along one of Montevideo’s main boulevards. The stamp was designed by Daniel Pereyra. (Courtesy Administración Nacional de Correos, Uruguay.)

Morquio’s moderation proved perceptive. As of 1915 Uruguay’s infant mortality record, although still better than most European levels, was stationary, if not worsening. This was particularly troubling given that the national birth rate was steadily declining.47 Morquio—who by this time had served as the medical director of the largest children’s asylum, chief of the pediatric clinic in the main public hospital, and a professor of clinical pediatrics—believed that some of the international measures adopted by Uruguayan health authorities had unintended consequences. He worried that milk stations discouraged breast-feeding by offering free or subsidized milk, and that this milk was often contaminated.48

Thereafter, numerous doctors chimed in on sometimes acerbic debates over the role of public health institutions, social and economic conditions, illegitimacy, abandonment, sanitation, climate, and cultural factors in Uruguay’s stagnating infant mortality.49 Such discussions were not unique to Uruguay, but they were unusual in the international attention they generated. Uruguayan authors were extremely prolific on this question, publishing more than 1000 journal articles related to child and infant health between 1900 and 1940 (estimate based on a bibliographic database compiled by A.-E.B.).

Morquio himself was a major contributor to Uruguay’s international renown, writing an average of 9 articles per year between 1900 and 1935. Almost half of his output appeared in foreign publications, including Archives de Médecine des Enfants (France), La Nipiología (Italy), Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases (United States), and the Archivos Latino Americanos de Pediatría, which he cofounded.50 Most of his articles focused on specific childhood medical problems, giving him credibility in the worlds of medicine and research as well as public health. Morquio became widely known for his 1917 book on gastrointestinal problems of infants, which was published in several languages and bridged his various interests. Numerous pieces he published in Uruguay were reissued by international journals. In 1928, for example, a talk he gave in Montevideo on infant mortality was reprinted in the Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana,51 which introduced it by emphasizing its “universal relevance.”

Almost as soon as they began to be compiled, Uruguay’s infant mortality statistics were viewed simultaneously in national and international terms. Scrutinized through comparative lenses, Uruguay initially deemed itself a success story. Conversely, as the problem of infant mortality stagnation unfolded domestically, the repercussions went far beyond the national realm.

URUGUAY’S HEALTH INTERNATIONALISM

By the 1920s the international health landscape consisted of a handful of permanent agencies, based principally in Europe and North America, with limited but growing prestige. In December 1902 the Union of the American Republics (precursor to the Organization of American States) sponsored the International Sanitary Convention in Washington, DC, at which the International Sanitary Bureau was founded. The International Sanitary Bureau, renamed the Pan American Sanitary Bureau (PASB) in 1923, was the world’s first international health agency.52

Operating out of the US Public Health Service under the directorship of the US surgeon general until the mid-1940s, the PASB worked on treaties and commercial concerns related to epidemic diseases, with quadrennial congresses creating an important venue for public health exchange among the region’s professionals. In 1907 the PASB established an International Sanitary Office in Montevideo for the collection of health statistics from South American countries, but the precariously funded office disappeared within a decade. The PASB’s sixth conference in Montevideo in 1920, at which US Surgeon General Hugh Cumming became director, marked a renewal of activity. The PASB’s widely distributed Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana was founded in 1922, the Pan American Sanitary Code was passed in 1924, and cooperative activities with member countries were also initiated in the 1920s.53,54

Another key agency involved in international health was the New York–based Rockefeller Foundation, founded in 1913. The foundation’s International Health Board launched a series of campaigns against hookworm, yellow fever, and malaria in Latin America and throughout the world, as well as establishing schools of public health in Europe, the Americas, and beyond.55,56 Interestingly, Uruguay was virtually the only country in the region untouched by the Rockefeller Foundation (perhaps because it no longer experienced any of the foundation’s showcase diseases), leaving the country all the more inclined to pursue public health approaches broadly.

In Europe it took more than half a century to transcend imperialist jealousies in order to establish a uniform system of disease notification and maritime sanitation. The culmination of 11 international sanitary conferences held since 1851, the Office International d’Hygiène Publique was founded in Paris in 1907 to hold periodic conferences, regulate quarantine agreements, and conduct studies on epidemic diseases. It also served as the international repository for health statistics before this responsibility was assumed by the World Health Organization in 1948.

The devastation of World War I lent new urgency to international health organizations. In 1921 the Geneva-based League of Nations founded an epidemic commission to control outbreaks of typhus, cholera, smallpox, and other diseases in Eastern and Southern Europe. The head of the epidemic commission, the Polish hygienist Ludwik Rajchman, ably transformed it into the League of Nations Health Organization (LNHO) in 1923. The LNHO helped war-torn nations reorganize their health bureaucracies and pursued an ambitious program of surveillance, research, standardization, professionalization, and technical aid. Under Rajchman (who later helped found UNICEF), the LNHO expressed a special concern for the health and welfare of children, working closely with the war relief agency Save the Children (founded in Britain in 1919, with an international counterpart established in Geneva in 1920).1,57

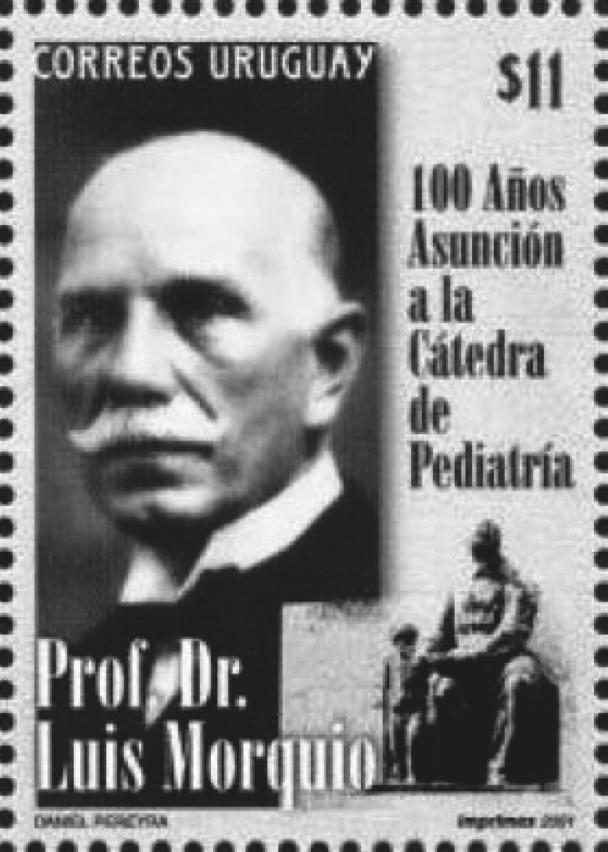

Uruguay became involved with the LNHO in the early 1920s, most notably through Paulina Luisi, the country’s first woman doctor and its leading liberal feminist.58–60 Active in regional feminist, scientific, and child welfare circles, Luisi soon leapt to prominence on the international scene. She was the only Latin American woman delegate to the first League of Nations Assembly, participating in various treaty, disarmament, and labor conferences. In 1924 she became an expert delegate on the League of Nations advisory commission on white slavery, and for 10 years she was one of only 2 Latin American delegates on the Committee for the Protection of Childhood (the other being an IIPI representative). Luisi forcefully advocated increased Latin American perspectives in the League of Nations’ work for children, including surveys of needs and policies as well as greater representation in governing bodies61–64 (Figure 3 ▶).

FIGURE 3—

Paulina Luisi, Uruguay’s first female doctor, with her Faculty of Medicine classmates in September 1901. (Photo courtesy of the Department of History of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay.)

THE BIRTH OF THE IIPI

Another key dimension of international organizing in this period consisted of periodic congresses, mostly held in Europe, devoted to questions of hygiene, demography, statistics, and child welfare.41 Two international associations for childhood protection were conceived in Brussels in 1907 and 1913, but their institutionalization was aborted and their activities were absorbed by League of Nations committees in the 1920s.

In the Americas, meanwhile, Pan American Child Congresses were launched in Buenos Aires in 1916, serving as a vibrant forum for Latin American reformers, feminists, physicians, lawyers, and social workers devoted to improving the health and welfare of poor and working-class women and children. The 8 hemispheric meetings held before World War II influenced the passage of dozens of laws delineating rights in such areas as adoption, infant health, state assistance, and child labor.65 Although the first Pan American Child Congress was organized by “maternalist feminists” who viewed the lot of children as inextricably linked to the rights of women as mothers,60,66 control over the Latin American child welfare movement was soon seized by male professionals, as evidenced by the preponderance of male presenters at the successful second congress, held in Montevideo in 1919. Even presider Paulina Luisi was upstaged by Luis Morquio’s high profile.67

It was at this congress that Morquio called for an international institute for childhood protection to be based in Montevideo, a proposal enthusiastically sanctioned by the Uruguayan government through a 1924 decree and approved by the fourth Pan American Child Congress, held in Santiago later that year.68 But the founding of the IIPI awaited an outside impetus, which—apparently thanks to Luisi—came in the guise of LNHO sponsorship of a conference held in June 1927 in Montevideo.

This conference, the South American Conference on Infant Mortality, was the first League of Nations conference of any kind to be held in Latin America. Attended by both Rajchman and the LNHO’s president, Danish bacteriologist Thorvald Madsen, the conference was a prestigious forum for Morquio and other experts in infant health and welfare.69 Through the IIPI, the LNHO backed a set of infant mortality surveys in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay similar to surveys it had sponsored in Europe.70,71 The results, presented at the Sixth Pan American Child Congress in Lima in 1930, demonstrated the need for improvements in vital statistics, centralization of services, and a range of public health, social assistance, economic, and educational measures to reduce infant mortality.72–74

The IIPI itself was launched by 10 participating countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Ecuador, Peru, the United States, Uruguay, and Venezuela; by 1949 the founders were joined by all other countries in the region), each with 1 official delegate. After 1936 the IIPI requested 2 representatives from each country—one technical and based in the home country, the other resident in Montevideo (a diplomat, for example). In the early years, most IIPI operating funds were provided by the Uruguayan government, with intermittent support from other member countries.

The IIPI’s charge was to collect and disseminate research, policy, and practical information pertaining to the care and protection of infants, children, and mothers. It sought to “[Latin] Americanize” the study of childhood so that the region was understood as distinct from and not just derivative or reflective of Europe.75 At the same time, the IIPI ensured that the region’s problems, research, and policies entered into international discussions. The IIPI’s widely circulated Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia, its library, its health education materials, and the child congresses it sponsored rapidly established its strong reputation and generated a large network of collaborators throughout Latin America and the world.76

In its first decade, the IIPI was governed by a group of distinguished physicians. Gregorio Aráoz Alfaro of Argentina served as president for the first 25 years of IIPI’s existence, with Uruguayan Víctor Escardó y Anaya as secretary. Morquio was the IIPI’s first director; after his death in 1935 his compatriot Roberto Berro held the position until 1956. In addition to editing the Boletín and working with the international advisory board, the director oversaw a small permanent staff who ran the Institute’s library and archive; collected laws, statistics, and reports on child protection from member countries and beyond; and sent information to correspondents around the world.76,77

The IIPI navigated complicated waters between independence and patronage. It was a consulting agency to both the League of Nations and the Panamerican Union until World War II, and in 1949 it was integrated into the Organization of American States. (The IIPI is now known as the Instituto Internacional del Niño, or International Institute of the Child.) The LNHO had hoped that its role in the IIPI would give it a foothold in various South American research and educational instititions,69 but tight resources in Geneva meant that the LNHO could do little more than encourage activities at the IIPI. (A lingering question is why the LNHO rather than the PASB provided the organizing spark for the IIPI, and whether the PASB’s territoriality—based as it was in US isolationist politics and a Monroe Doctrinism applied to health—helped derail the LNHO’s ambitious plans in Latin America.)

The IIPI propelled Uruguay to international attention. In 1930 Morquio was named to the presidency of Save the Children in Geneva, providing a worldwide platform for the policies and practices he and other Uruguayans had developed. The Pan American Child Congresses continued to meet until 1942, offering a key venue for exchange of ideas and learning during a period of fertile social policy activity throughout the region.65

Perhaps most visibly, the IIPI’s Boletín, founded shortly after the 1927 conference, brought considerable acclaim to Uruguay. Unique in its scope, the IIPI’s Boletín—published quarterly in English, French, and Spanish—covered topics ranging from the organization of children’s social services to summer camps, school health, sports, education, health campaigns, marginalized children, and the causes of infant or child mortality. It was one of the most international journals of its day: of the 1000 authors published in the journal’s first 2 decades, approximately one fifth were from Europe and North America and four fifths from throughout Latin America. Slightly more than one third of the authors were Uruguayan. A small number of Uruguayan pieces profiled child welfare systems in other countries, but for the most part Uruguayans used the IIPI’s Boletín to highlight domestic problems and achievements in infant, child, and maternal welfare.

URUGUAY’S CHILDREN’S CODE

As the Uruguayan public health community grappled with the continued stagnation of its infant mortality rates, it became clear that increasingly specialized medical approaches were insufficiently integrated with social provisions for child health. This realization offered a chance for IIPI influences to be expressed through local developments, but in 1933 Uruguay’s liberal era came to a sudden end with the dictatorship–cum–conservative-populist government of Gabriel Terra. Rather than impede integrated child welfare policy, however, Terra’s efforts to rationalize and centralize power reinforced the country’s widely supported protectionism78,79: the IIPI served as a social policy umbrella under which new initiatives were researched and debated.

In 1933 Morquio, Bauzá and other colleagues were invited by the just-founded Ministry of Child Protection—the first of its kind in the world—to form a legislative advisory commission to organize the various programs and agencies involved in infant and child welfare in Uruguay. Under the leadership of Roberto Berro, a disciple of de Salterain and Morquio and an advocate of “childhood social medicine,”80 the commission did not limit itself to the administrative process of merging overlapping agencies. Instead, it called on the country to adopt a children’s code spelling out children’s rights to health, welfare, education, legal protections, and decent living conditions and creating specific institutions to run and oversee child and maternal aid programs.

Following a lively debate in Uruguay’s national Assembly, the unanimous recognition by foreign delegates to the Seventh Pan American Conference in 1933 that such a code would put Uruguay “in the vanguard,” and expressions of broad professional and popular support, the Uruguayan parliament approved the Children’s Code in 1934. With passage of the code, the Uruguayan government explicitly recognized the importance of integrating medical approaches to the improvement of child health with social approaches, including better housing, sanitation, road-paving, schools, and family allowances81 (Figure 4 ▶).

FIGURE 4—

Annotated version of Uruguay’s Children’s Code.

To enable its interdisciplinary work and avoid turf battles with other ministries, the Ministry of Child Protection was refashioned into the Consejo del Niño (Children’s Council) under the Ministry of Public Education. Although the Consejo was headed by a series of doctors, it was purposely separated from the new Ministry of Public Health (established in 1934) to emphasize its social, rather than medical, approach to child well-being. The Consejo organized its services by age group (prenatal, infant, child, and adolescent divisions) and jurisdiction (education, law, social services, and school health divisions), establishing offices throughout the country and absorbing a series of kindergartens, orphanages, asylums, homes, camps, and reform institutions. With this purview, the Consejo reached virtually every Uruguayan child, at minimum through school health exams and, for poor and working-class children, through extensive coordinated services.82,83

The relationship between the IIPI and the Consejo was very close, with ongoing exchange of staff and ideas. Berro, for example, directed the Consejo before becoming head of the IIPI; Bauzá was an IIPI representative before becoming a division head and then director of the Consejo. Descriptions and assessments of Consejo projects were frequently published in the IIPI’s Boletín, probably bringing Consejo activities to greater international attention than the children’s services of any other country.84,85

Although several other countries had previously enacted children’s codes—and Save the Children founder Eglantyne Jebb’s Declaration of the Rights of the Child had been adopted by the League of Nations in 1924—these efforts were more symbolic than substantive. It was Uruguay—with its well-developed welfare state, close links to the IIPI, anxiety about infant mortality, and international profile—that offered an implementable model of children’s rights in a particular national setting. Through the IIPI, the PASB, the LNHO, and other networks, Uruguay’s experience became widely known and discussed, particularly as its infant mortality rates finally began to improve in the late 1930s. Countries with active social medicine movements, such as late-1930s Chile under the leadership of Minister of Health Salvador Allende,86 built upon and strengthened Uruguay’s efforts. The IIPI and PASB jointly issued the Pan American Children’s Code in 1948, and in 1989 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child, both of which drew extensively on the Uruguayan code.

Uruguay’s Children’s Code was the effort of decades of activism on the part of several generations of Uruguayan public health and social welfare advocates whose domestic work enjoyed international recognition. It was the interaction between Uruguay’s international leadership and the protectionist Batllista state that, despite its flaws and slow pace, provided a laboratory of legislation and practice in the area of children’s well-being.

CONCLUSIONS

As this examination of the founding and activities of the IIPI demonstrates, the institutional panorama of international health included more than the “usual suspects” among metropolitan organizations. With existing agencies in place in the United States and Europe, Uruguay did not seem a propitious locale for a new international health office. But the country used its strengths—a stable welfare state, well-placed professionals, leadership in child health—and its weaknesses—small size, remoteness, persistent infant mortality problems—to secure a place on the world stage. A key additional ingredient for establishing the IIPI in Uruguay was the legitimacy provided by the country’s ties to another international agency—the League of Nations. In obtaining the League’s support, the cosmopolitan physicians who anchored Uruguay’s international engagement in public health benefited from the essential legwork of the “maternalist feminists” who had launched the Pan American Child Congresses.

It might be suggested that Uruguay was able to carve out a niche in international health that was of little moment to the larger community. But given the LNHO’s early interest in the IIPI, the extensive worldwide concern with maternal and child health that was manifested during this period,19 and the international attention that was later paid to children’s health through such organizations as UNICEF,87 this thesis holds little water. Still, in 1927 children did not top the list of concerns of the PASB, which would have been the IIPI’s logical patron. With several PASB conferences in the 1920s (including the 1920 Montevideo meeting), there was ample opportunity for sponsorship. But the PASB spent its first decades focused on the interruption of commerce caused by epidemic diseases, even as the delegates to its conferences requested attention to other health priorities.88 Making faraway Montevideo into “the Geneva of South America” does not seem to have irked PASB Director Cumming: the PASB was officially supportive of the IIPI,89 though Cumming failed to mention the IIPI in several key overviews of health cooperation that he published.90

Once the IIPI was established, maternal and child health took on a higher profile at the PASB, particularly in its Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. Child well-being finally reached the PASB’s agenda at its ninth conference, held in Buenos Aires (together with the Latin American Eugenics and Homiculture Congress) (“Homiculture” is a Cuban-coined term expanding Pinard’s concept of puericulture to include cultivation of the child from prebirth to adulthood.) in 1934, shortly after the passage of Uruguay’s Children’s Code. The PASB supported the position articulated by the IIPI’s Berro, which fostered “positive” eugenics as embracing a “broad, non-coercive public health and social welfare approach directed toward the child” in contrast to the United States’s focus on heredity and sterilization.91 Given the IIPI’s activities and its very existence—bolstered by the advocacy of several member countries—the PASB could no longer overlook maternal and child health.

The IIPI’s modus operandi differed significantly from that of other international health agencies. Rather than evolving into a regional outpost of the LNHO or the PASB, it maintained cordial relations free of “parental” constraints. Owing to the combination of fortunate timing, Uruguayan government support, and the regional backing of child health Pan-Americanists, the IIPI remained unencumbered by imperial or industrial interests. It drew its agenda from the concerns of health experts, feminists, and child advocates grounded in local problems in settings where child health policies were intertwined with burgeoning protectionism. The “Uruguay round” of international health suggests that the field is shaped by more than center–periphery logic.

Acknowledgments

Partial funding for the writing of this paper was provided by the Global Health Trust’s Joint Learning Initiative on Human Resources for Health and Development and the Canada Research Chairs program. The initial research was funded by the National Institute on Aging (grant 16813-01) and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (grant 37962-02).

I am grateful to Gregory Kim for carrying out the analysis of the Boletín of the IIPI. My thanks to Sandra Burgues, Fernando Mañé Garzón, Raquel Pollero, Wanda Cabella, and Nikolai Krementsov for their helpful comments and suggestions, as well as to the “Public Health Then and Now” editors and the anonymous reviewers.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Weindling P. International Health Organisations and Movements, 1918–1939. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

- 2.Packard R. “No other logical choice”: global malaria eradication and the politics of international health in the postwar era. Parassitologia. 1998;40:217–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqi J. World Health and World Politics: The World Health Organization and the UN System. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press; 1995.

- 4.Hutchinson JF. Champions of Charity: War and the Rise of the Red Cross. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press; 1996.

- 5.Farley J. To Cast Out Disease: A History of the International Health Division of Rockefeller Foundation (1913–1951). New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004.

- 6.Anuario Estadístico del Uruguay. Censo General de la República en 1908. Montevideo, Uruguay: Imprenta Juan Dornaleche; 1911.

- 7.Panizza F. Late institutionalisation and eary modernisation: the emergence of Uruguay’s liberal democratic political order. J Latin Am Stud. 1997;29:667–691. [Google Scholar]

- 8.López-Alves F. State Formation and Democracy in Latin America, 1810–1900. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2000.

- 9.Engerman SL, Haber S, Sokoloff KL. Inequality, institutions, and differential paths of growth among New World economies. In: Menard C, ed. Institutions, Contracts, and Organizations. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2000.

- 10.Nahum B. La Epoca Batllista, 1905–1929. In: Historia Uruguaya. Montevideo, Uruguay: Ediciones de la Banda Oriental; 1994:140.

- 11.Vanger MI. The Model Country: José Batlle y Ordeñez of Uruguay, 1907–1915. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England; 1980.

- 12.Pelúas D. José Batlle y Ordóñez : el hombre. Montevideo, Uruguay: Editorial Fin de Siglo; 2001.

- 13.Barrán JP, Nahum B. Crisis y radicalización 1913–1916. In: Batlle, los Estancieros y el Imperio Británico. Montevideo, Uruguay: Ediciones de la Banda Oriental; 1985:257.

- 14.Bértola L. Ensayos de historia económica: Uruguay y la región en la economía mundial, 1870–1990. Montevideo, Uruguay: Ediciones Trilce; 2000.

- 15.Filgueira F. A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay: Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State. Notre Dame, Ind: Kellogg Institute for International Studies; 1995. Democracy and Social Policy Series, Working Paper No. 5.

- 16.Moll A. The Pan American Sanitary Bureau: its origin, development and achievements: a review of inter-American cooperation in public health, medicine, and allied fields. Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. 1940; 19:1219–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peard JG. Race, Place, and Medicine: The Idea of the Tropics in Nineteenth-Century Brazilian Medicine. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1999.

- 18.Koven S, Michel S. Mothers of a New World: Maternalist Politics and the Origins of Welfare States. New York, NY: Routledge; 1993.

- 19.Fildes V, Marks L, Marland H. Women and Children First: International Maternal and Infant Welfare, 1870–1945. London, United Kingdom: Routledge; 1992.

- 20.Vaillant A. La República Oriental del Uruguay en la Esposición de Viena. Montevideo, Uruguay: Imprenta a vapor de La Tribuna; 1873.

- 21.Rial J. Población y Desarrollo de un Pequeño País: Uruguay, 1830–1930. Montevideo, Uruguay: Centro de Informaciones y Estudios del Uruguay; 1983.

- 22.Mañé Garzón F, Burgues Roca S. Publicaciones Médicas Uruguayas de los Siglos XVIII y XIX. Montevideo, Uruguay: Universidad de la República, Facultad de Medicina, Oficina del Libro AEM; 1996.

- 23.Buño W. Nómina de egresados de la Facultad de Medicine de Montevideo entre 1881 y 1965. Apartado de Sesiones de la Sociedad Uruguaya de Historia de la Medicina. 1992;IX (1987–88).

- 24.Dirección de Estadística General. Anuario Estadístico de la República Oriental del Uruguay. Año 1884. Libro I del Anuario y XV de las Publicaciones de esta Dirección. Montevideo, Uruguay: Tipografía Oriental; 1885.

- 25.Ramiro Fariñas D, Sanz Gimeno A. Cambios estructurales en la mortalidad infantil y juvenil española. Boletín de la Asociación de Demografía Histórica. 1999;17:49–87. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolleswinkel–van den Bosch JH, Poppel FW, Looman CW, Mackenbach JP. Determinants of infant and early childhood mortality levels and their decline in the Netherlands in the late nineteenth century. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corsini CA, Viazzo PP. The Decline of Infant and Child Mortality: The European Experience 1750–1990. Cambridge, Mass: Kluwer Law International; 1997.

- 28.Catálogo de la Exposición Internacional de Higiene. Enero–Abril de 1907. Montevideo, Uruguay: Talleres Gráficos A. Barreiro y Ramos; 1907:39.

- 29.El Uruguay en el V Congreso Médico Latino-Americano (VI Pan-Americano) y Exposición Internacional de Higiene anexa. Lima, Noviembre de 1915. Boletín del Consejo Nacional de Higiene. 1913;8:515–524. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soiza Larrosa A. La mortalidad de la ciudad de Montevideo durante el año 1893, por el Dr. Joaquín de Salterain, miembro del Consejo de Higiene Pública. Del retrospecto de El Siglo. Sesiones de la Sociedad Uruguaya de Historia de la Medicina. 1987;5:188–191. [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Salterain J. Boletín demográfico de la ciudad de Montevideo. Revista Médica del Uruguay. 1899;2:41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertillon J. Nomenclature des Maladies (Statistiques de Morbidité—Statistiques des Causes de décès). Commission Internationale Chargée de Reviser les Nomenclatures Nosologiques. Paris, France: Imprimerie Typographique de l’Ecole d’Alembert; 1900.

- 33.Transactions of the Fifteenth International Congress of Hygiene and Demography. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1912.

- 34.Rollet C. Le modèle de la goutte de lait dans le monde: diffusion et variantes. In: Les Biberons du Docteur Dufour. Fécamp, France: Musées Municipaux de Fécamp; 1997:111–117.

- 35.Becerro de Bengoa M. Los problemas de la asistencia pública. Segundo Congreso Médico Nacional. Montevideo, Uruguay: Imprenta El Siglo Ilustrado; 1921.

- 36.Ehrick C. Affectionate mothers and the colossal machine: feminism, social assistance and the state in Uruguay, 1910–1932. The Americas. 2001;58: 121–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asistencia Pública Nacional. Acta 312 (asunto: Sociedad Bonne Garde solicita una subvención). Boletín de la Asistencia Pública Nacional. 1918;8:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 38.El Año de los Niños. Montevideo: Asociación Uruguaya de Protección a la Infancia; 1925.

- 39.Cabella W. La evolución del divorcio en Uruguay (1950–1995). Notas de Población. 1998;XXVI.

- 40.de Salterain J. La mortalidad en la ciudad de Montevideo durante el año de 1895. Año III del Retrospectivo de “El Siglo.” Montevideo, Uruguay: Museo Histórico Nacional, Casa de Lavalleja, Archivo y Biblioteca Pablo Blanco Acevedo; 1896.

- 41.Rollet C. La santé et la protection de l’enfant vues à travers les congrès internationaux (1880–1920). Annales de Démographie Historique. 2001:97–116.

- 42.Bauzá J. Mortalidad infantil en la República del Uruguay en el decenio 1901–1910. Revista Médica del Uruguay. 1913;16:45–81. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morquio L. Cuatro años del servicio externo del Asilo de Expósitos y Huérfanos. Revista Médica del Uruguay. 1900;3.

- 44.Escardó y Anaya V. Biografía del Profesor Luis Morquio. Archivos de Pediatría del Uruguay. 1935;6:250–276. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morquio L. La mortalidad infantil de Montevideo. In: Tercer Congreso Médico Latinoamericano, Montevideo 1907. Montevideo, Uruguay: Imprenta El Siglo Ilustrado; 1907:547–585.

- 46.Morquio L. Causas de la Mortalidad de la Primera Infancia y Medios de Reducirla. Informe Presentado al 2do Congreso Médico Latino-Americano Celebrado en Buenos Aires en Abril de 1904. Montevideo, Uruguay: Imprenta El Siglo Ilustrado; 1904.

- 47.Primer Congreso Médico Nacional: Sección de Pediatría, presidida por el Dr. Luis Morquio. Revista Médica del Uruguay. 1916;19:666–678. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morquio L. Protección a la primera infancia. Primer Congreso Médico Nacional. Montevideo, Uruguay: Imprenta El Siglo Ilustrado; 1916.

- 49.Birn A-E, Pollero R, Cabella W. No se debe llorar sobre leche derramada: el pensamiento epidemiológico y la mortalidad infantil en Uruguay, 1900–1940. Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina. 2003;14:35–65. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Escardó y Anaya V. Bibliografía del Profesor Morquio. Montevideo, Uruguay: Instituto de Pediatría y Puericultura “Profesor Luis Morquio”; 1938.

- 51.Morquio L. La mortalidad infantil en Uruguay. Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. 1928;7: 1466–1475. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Transactions of the First General International Sanitary Convention of the American Republics, Held at the New Willard Hotel, Washington, D.C., December 2, 3, and 4, 1902, Under the Auspices of the Governing Board of the International Union of the American Republics. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1902.

- 53.Bustamante M. Los primeros cincuenta años de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. 1952;33: 471–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moll A. The Pan American Sanitary Bureau: its origin, development and achievements: a review of inter-American cooperation in public health, medicine, and allied fields (continued). Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. 1941;20:375–380. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cueto M. Missionaries of Science: The Rockefeller Foundation and Latin America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1994.

- 56.Fosdick R. The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1952.

- 57.Balinska M. Une Vie pour L’humanitaire: Ludwik Rajchman (1881–1965). Paris, France: Editions la Découverte; 1995.

- 58.Ehrick C. Madrinas and missionaries: Uruguay and the Pan-American women’s movement. Gender Hist. 1998; 10:406–424. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sapriza G. Memorias de Rebeldía: Siete Historias de Vida. Montevideo, Uruguay: Punto Sur Editores; 1998.

- 60.Lavrin A. Women, Feminism, and Social Change in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1995.

- 61.Scarzanella E. Proteger a las madres y los niños: el internacionalismo humanitario de la Sociedad de las Naciones y las delegadas sudamericanas. In: Potthast B, Scarzanella E, eds. Mujeres y Naciones en América Latina: Problemas de Inclusión y Exclusión. Madrid, Spain: Iberoamericana Editorial Vervuert; 2001.

- 62.Luisi P. Otra voz clamando en el desierto (Proxenetismo y reglamentación). Montevideo, Uruguay: CISA; 1948:1.

- 63.Rooke PT, Schnell RL. “Uncramping child life”: international children’s organisations, 1914–1939. In: Weindling P, ed. International Health Organisations and Movements, 1918–1939. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1995:176–202.

- 64.Miller C. The Social Section and Advisory Committee on Social Questions of the League of Nations. In: Weindling P, ed. International Health Organisations and Movements, 1918–1939. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1995:154–175.

- 65.Guy D. The Pan American Child Congresses, 1916 to 1942: Pan Americanism, child reform, and the welfare state in Latin America. J Family Hist. 1998;23:272–291. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller F. Latin American Women and the Search for Social Justice. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England; 1991.

- 67.Guy DJ. The politics of Pan-American cooperation: maternalist feminism and the child rights movement, 1913–1960. Gender Hist. 1998;10: 449–469. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antecedentes Publicados por la Comisión Honoraria. Montevideo, Uruguay: Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia; 1925:21.

- 69.Madsen T. Report by the president of the Health Committee on his technical mission to Certain South American Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: League of Nations Archives, Assemblée 8, 1927, Decs 39–133; September 16, 1927.

- 70.Scarzanella E. “Los pibes” en el Palacio de Ginebra: las investigaciones de la Sociedad de las Naciones sobre la infancia latinoamericana (1925–1939). Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe. 2003;14.

- 71.Madsen T. Report on the work of the Conference of Health Experts on Infant Welfare held at Montevideo from June 7th to 11th, 1927. Geneva, Switzerland: League of Nations Archives, Assemblée 8, 1927, Decs 39–133; September 16, 1927.

- 72.Debré R, Olsen EW. Société des Nations, Organisation d’Hygiène. Les enquêtes entreprises en Amérique du Sud sur la mortalité infantile. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1931;4: 581–605. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morquio L. Société des Nations, Organisation d’Hygiène. Conférence d’experts hygiénistes en matière de protection de la première enfance. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1931;4:535–580. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aráoz Alfaro G. Société des Nations, Organisation d’hygiène. Experts hygiénistes en matière de protection de la 1ère enfance. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1931;4:373–425. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fournié E. Séptima Conferencia Internacional Americana, Capítulo V: problemas sociales. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1934;7:229–249. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Escardó y Anaya V. Veniticinco anos del Consejo Directivo y de la Dirección General. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1952;26:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morquio L. Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia: noticia presentada al VI congreso panamericano del niño. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1930;4:215–229. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Caetano G. Prólogo. In: El Uruguay de los Años Treinta: Enfoques y Problemas. Montevideo, Uruguay: Ediciones de la Banda Oriental; 1994:7–15.

- 79.Caetano G, Jacob R. El Nacimiento del Terrismo, 1930–1933. Montevideo, Uruguay: Ediciones de la Banda Oriental; 1989.

- 80.Berro R. La medicina social de la infancia. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1936;9:594–609. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tomé E. Código del Niño. Anotado con todas las leyes, decretos y acordadas vigentes y con la jurisprudencia nacional. In: Colección de Manuales de Derecho y Legislación. Montevideo, Uruguay: Claudio García Editor; 1938.

- 82.Consejo del Niño. Consejo del Niño, Su Organización y Funcionamiento 1934–1936. Montevideo, Uruguay: Imprenta de Monteverde & Cia; 1937?:81.

- 83.Guía Informativa de las Funciones que Desarrolla el Consejo del Niño. Montevideo, Uruguay: Consejo del Niño; 1950.

- 84.Quesada Pacheco R. Informe sobre la Obra de Protección a la Infancia realizada por el Consejo del Niño del Uruguay. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1937;11:261–283. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bauzá JA. Acción futura del Consejo del Niño. Boletín del Instituto Internacional Americano de Protección a la Infancia. 1943;17:291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Illanes MA. En el Nombre del Pueblo, del Estado y de la Ciencia . . . : Historia Social de la Salud Pública, Chile 1880–1973. Santiago, Chile: Colectivo de Atención Primaria; 1993.

- 87.Gillespie J. International organizations and the problem of child health, 1945–1960. Dynamis. 2003;23: 115–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Birn A-E. No more surprising than a broken pitcher? Maternal and child health in the early years of the Pan American Sanitary Bureau. Can Bull Med Hist. 2002;19:17–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moll A. Las obras sanitarias de protección a la infancia en las Américas. Boletín de la Organización Sanitaria Panamericana. 1935;14:1040–1055. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cumming HS. Development of international cooperation among the health authorities of the American republics. Am J Public Health. 1938;28: 1193–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stepan N. The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1991.