Abstract

The drawings of Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli, a prisoner confined in a Pennsylvania “close-security” or “supermaximum” prison, tell a story—one that graphically portrays the devastating effects of a prison on the mental health of its inmates.

FOR A NUMBER OF YEARS, Todd has sent his drawings to Bonnie Kerness of the American Friends Service Committee; it was through her that I first saw them and eventually corresponded with Todd about using them to illustrate my ethnographic work on prisons. In this article, I use Todd’s drawings to make 3 points about confinement in US supermaximum prisons: (1) it plays a role in producing or exacerbating mental illness in prison; (2) it affects the psychology and self-perception of prisoners, whether or not they can be described as mentally ill; and (3) it raises broader questions about the larger or “collateral” effects of the US prison complex. I draw on my ethnographic work in Washington State prisons and on interviews that I and my colleagues conducted from 1999 to 2002 as part of a collaborative effort by the University of Washington and the Washington Department of Corrections to address issues of prison mental health.1

CONFINEMENT IN SUPERMAXIMUM PRISONS

Prisoners like Todd are held in fortresslike facilities under a regime of complete isolation. Confined in single, sometimes windowless, cells for 23 or more hours a day, they are completely dependent on the prison staff who walk the tiers, pushing meals, mail, and toilet paper through ports in the heavy doors of the cells. Inmates are taken out—cuffed, often shackled, and under guard—only for showers or brief exercise in solitary yards. This extreme form of confinement goes beyond the “segregation” that has always been a necessary aspect of imprisonment. Prison officials and the media often refer to prisoners in supermaximum facilities as the “worst of the worst,” but although some of these inmates have committed serious crimes, it is primarily behavior in prison rather than criminal history that determines placement. In addition, not all supermaximum prisoners are being punished for serious misbehavior within the prison. Some may be under protective custody or in preventive detention, while others may have committed a number of relatively minor infractions against prison rules.

Exact figures on supermaximum confinement are not available, but we know that the United States has more than 60 such facilities housing a total of well over 20 000 people.2 These facilities, which had been constructed during the expansion of the US prison complex that began in the early 1980s, share the punitive and individualistic philosophy that accompanied that expansion. Behavior in prison, like crime itself, has increasingly come to be understood primarily as a matter of individual choice divorced from its social context. Thus, for example, a supermaximum prisoner deprived of all but the most minimal options is offered the “choice” of returning a meal tray or keeping it in his cell as a gesture of defiance. Defiant behavior is then cited as proof that this form of confinement is necessary.

Many factors, including political pressure for harsh sentencing, the effect of enemployment on rural economics, population pressure inside prison systems, and the internal architectural and staffing features of general-population units, influence the construction and use of supermaximum facilities across the country. Local administrators often have few options for reducing tension among prisoners, rewarding good behavior, or placing disruptive or mentally ill prisoners. These issues, however, are seldom part of public debate about prisons and prison spending. Supermaximum prisons are generally off-limits to the public, and the claim that they house the “worst of the worst” is rarely questioned in the press. Yet although supermaximum inmates are a small percentage of the total prison population, these facilities constitute a pragmatically and philosophically important aspect of the prison system as a whole. We can also see, in the very existence of this intense form of isolation, a concentration of some of the most important negative effects of the entire prison complex.

DECOMPENSATION

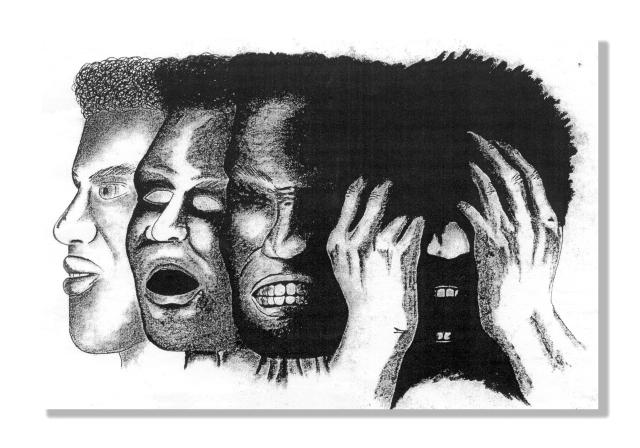

Todd based his drawing Decompensation on his observation of prisoners held for years under supermaximum confinement (Image 1 ▶). It depicts what prisoners call “breaking”—that is, losing one’s mind under extreme conditions of deprivation and isolation. Leena Kurki and Norval Morris, describing the Tamms supermaximum facility in Illinois, write that “these are harsh conditions for anyone, but . . . they are formidably harsh . . . for the mentally ill and those teetering on the brink of mental illness.”3(p401) Some supermaximum prisoners describe experiences of anxiety, rage, dissociation, and psychosis. One man who had been in and out of isolation for several years said, “Sometimes I see things that is on the wall. . . . Sometimes I hear voices. . . . There is nobody to talk to . . . and vent my frustration and, as a result, sometimes I am violent. Pound on the walls. Yell and scream.” Speaking of the possibility of transferring to a mental health facility, he said, “I wanted to die and I wanted some help.”1

IMAGE 1—

Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli, Decompensation.

There are 2 senses, not sharply distinguishable, in which a prisoner in supermaximum confinement may “break.” First, the deinstitutionalization of psychiatric hospitals, changes in sentencing, and other outside pressures have resulted in increasing numbers of incarcerated individuals with serious mental illness. A 1989 study of Washington State inmates indicated that 10% to 15% of the state’s prison population was mentally ill.4 This use of the prison as an “asylum of last resort”5 means that mentally ill individuals find themselves in the “general population” units where most prisoners live. The crowded conditions, frightening interactions with other inmates, and multitude of prison rules are overwhelming for many prisoners, but even more so for those whose judgment and perception are impaired.

Although Washington State provides medium and maximum security psychiatric facilities, the number of mentally ill inmates far exceeds available beds. One consequence is that some disturbed prisoners—often those with multiple mental and physical problems—are held in supermaximum units. While some of these inmates may be sent to specialized treatment units when they deteriorate further, others are considered too dangerous—or perhaps too “manipulative”—for treatment. We found that 20% to 25% of supermaximum inmates showed strong evidence of mental illness.6

Even without a prior clinical condition, however, a prisoner may “break” under supermaximum confinement. Critical accounts of supermaximum prisons emphasize the negative effects of solitary confinement on the mental condition of many prisoners who experience extreme states of rage, depression, or psychosis. For example, social psychologist Hans Toch noted that “The most extreme punitive confinement—supermaximum isolation—most heavily taxes limited coping competence, and leads, literally, to points of no return . . . prison cells become filled with prisoners who have withdrawn from painful reality and quietly hallucinate. Their symptoms, their torpor, incoherent mumbling, restless sleep, and waking nightmares are difficult . . . for casual observers to spot, and noncasual observers are unwelcome in punitive segregation facilities.”7(pxii) Even when symptoms are obvious to staff, they may be influenced by a lack of resources, the pervasive emphasis on inmate “manipulation,” and distrust of social or psychological explanations of behavior. Staff who hold a strong belief in individual “choice” and who are charged with treating all inmates “equally” may not regard their withdrawn, angry, or delusional charges as needing attention.

CAPTURING THE MIND

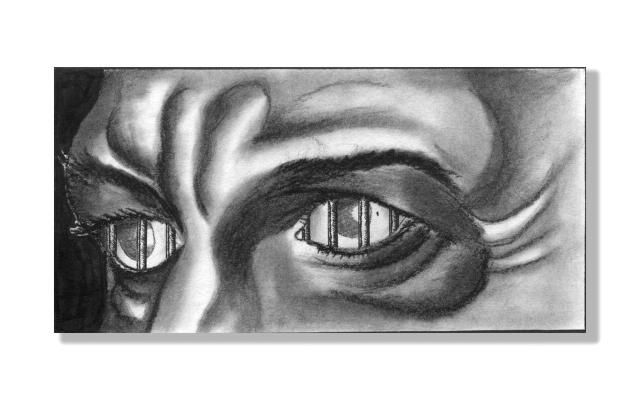

In another of Todd’s drawings, we see a pair of eyes striped with prison bars (Image 2 ▶). As he wrote in a letter, “The drawing with the eyes represents how prison makes you view things.” An axiom of imprisonment since the beginning of the modern era has been that it works on the mind by means of the body, bringing about penitence or “teaching a lesson” by changing how the prisoner “views things.” Some prisoners do, indeed, experience positive changes. Some, like Todd, also find ways to question the social numbing and psychological deterioration they see around them. But Todd’s drawing suggests that a more negative outcome is also possible: the internalization of prison bars and—by implication—of the logic and culture of the prison in the mind of the prisoner.

IMAGE 2—

Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli, untitled drawing.

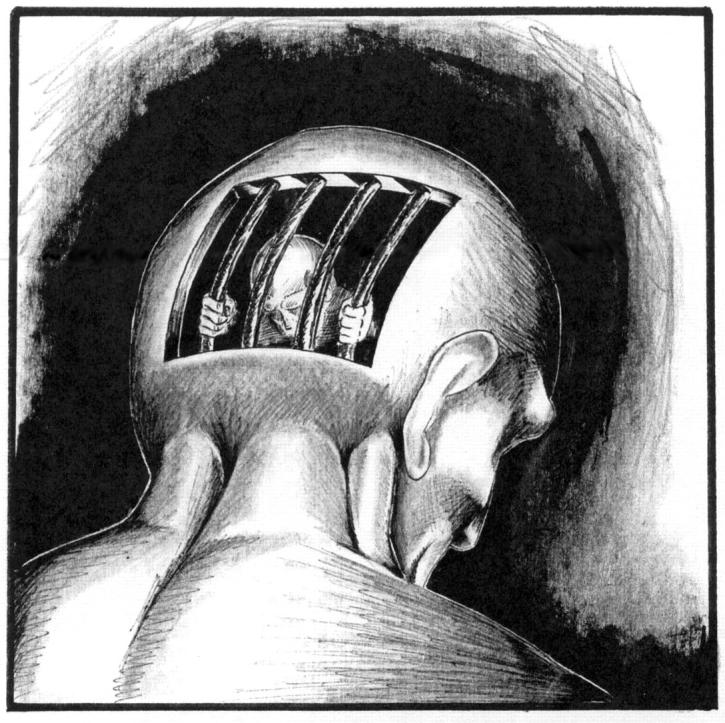

In a second drawing on this theme, entitled Captive, a barred head confines a prisoner who is clearly the same person (Image 3 ▶). Todd wrote that this represents “both the imprisoned body and the mind. . . . Captive was supposed to be symbolic of the ‘mental blocks’ or limitations that people have [making] them unable to think beyond given boundaries.” Prison systems aim to “make people unable to think beyond given boundaries,” Todd wrote, in the sense that they see limit-setting and the imposition of boundaries as their primary job. For example, inmates should not be able to think realistically of escape. They are to align their own boundaries with those of the prison and turn their thoughts to self-improvement.

IMAGE 3—

Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli, Captive.

All inmates find themselves having to come to terms with these boundaries, but most do so in the context of interaction with others and—at least to some extent—with the outside world. Supermaximum prisoners, however, held for long periods with almost no human interaction, may develop distorted personal boundaries that make it difficult for them to be in contact with others. They may become increasingly incapable of social life; as psychologist Craig Haney points out, the extreme dependency fostered by this form of confinement can result in an inability to initiate action or to exercise normal self-management in social situations.8,9 Furthermore, even those prisoners who do not appear to deteriorate in supermaximum confinement—who, in prison parlance, “maintain”—may nevertheless suffer damaging psychological effects. In interviews, some prisoners spoke of compulsive and sometimes violent ruminations; one man said that “All day long I was thinking about chopping people up, chopping their families up, and stuff like that.” Isolation, dependency, and impersonal management were described by prisoners as contributing to their rage.

COLLATERAL DAMAGE

In the drawing Collateral Damage, we see the silhouette of an imprisoned man who appears to be trying to hug a child through the bars, while the child, too, opens his arms (Image 4 ▶). While the drawing’s immediate meaning is that the incarceration of parents also harms children, it can also be understood in a larger, more symbolic sense. Many consequences of prison expansion are a form of “collateral damage,” including the spread of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C, damage to communities through the incarceration of generations of young people, and the lifetime effects of incarceration on those who have served their sentences. Marc Mauer and Media Chesney-Lind wrote that “Rather than investigating the circumstances of families or communities that enhance social solidarity and communicate shared values, a criminal-justice centered policy applies a reactive, and increasingly punitive, approach to the resolution of social conflict.”10 The result is not only that massive incarceration has consequences for prisoners, families, and communities, but that it consumes the resources, energy, and—not insignificantly—creative thinking that might be devoted to other solutions.

IMAGE 4—

Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli, Collateral Damage.

In the case of supermaximum imprisonment, the consequences extend first to the families of prisoners, whose visits may be tightly restricted and who are allowed to see their imprisoned family members only through the thick plastic window of a visiting booth. Some long-term prisoners say that they do not want their families to see them under these circumstances—a point suggested in Todd’s drawing by the shaded figure of the father—and gradually cut off contact. Consequences also extend to the staff of these prisons, many from rural towns, who learn a numbingly mechanistic, impersonal, and potentially brutalizing form of work. Some prison workers are able to resist these effects, but many develop a punitive attitude that eventually affects their families and communities. In addition, communities are affected by the release of prisoners who may have lost whatever social skills and self-control they had when they went to prison, and who in some cases may be psychologically damaged beyond repair.

Todd’s drawings can also tell us a larger story. To what extent are these pictures of the pathological effects of the prison also about “us”—even those of us who have no obvious contact with the institutions themselves? These drawings suggest that perhaps, in a country that supports the world’s largest prison system,11 prisons have indeed become embedded in our collective mind. The massive presence of prison as a solution to social problems shapes the boundaries of what we think is possible, narrowing options not only for the incarcerated and their families and communities but also for those of us who imagine ourselves far away from life on the “inside.”

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli, Bonnie Kerness, David Allen, David Lovell, Kristen Cloyes, Cheryl Cooke, the Washington State Department of Corrections, and the prisoners who participated in the University of Washington/Department of Corrections Mental Health Collaboration.

References

- 1.Rhodes LA. Total Confinement: Madness and Reason in the Maximum Security Prison. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2004.

- 2.National Institute of Corrections. Supermax Housing: A Survey of Current Practice. Longmont, Colo: US Dept of Justice; 1997.

- 3.Kurki L, Morris N. The purposes, practices and problems of supermax prisons. In: Tonry M, ed. Crime and Justice: A Review of Research. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press; 2001: 385–424.

- 4.Kemelka R, Trupin E, Chiles JA. The mentally ill in prison: a review. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989; 40:481–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamb HR, Weinberger LE. Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 1998; 49(4):483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovell D, Cloyes C, Allen DG, Rhodes LA. Who lives in supermaximum custody? A Washington State study. Fed Probat. 2000;61:3:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toch H. Forward. In: Kupers T. Prison Madness: The Mental Health Crisis Behind Bars and What We Must Do About It. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1999:ix–xiv.

- 8.Haney C. “Infamous punishment”: the psychological consequences of isolation. Natl Prison Project J. 2003(spring): 2–21.

- 9.Haney C. Mental health issues in long-term solitary and “supermax” confinement. Crime Delinqu. 2003;49(1): 124–156. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauer M, Chesney-Lind M. Introduction. In: Mauer M, Chesney Lind M, eds. Invisible Punishment The Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment. New York, NY: New Press; 2002:1–12.

- 11.US Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2003. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/prisons.htm. Accessed July 18, 2005.