Abstract

The American system of prisons and prisoners—described by its critics as the prison–industrial complex—has grown rapidly since 1970. Increasingly punitive sentencing guidelines and the privatization of prison-related industries and services account for much of this growth.

Those who enter and leave this system are increasingly Black or Latino, poorly educated, lacking vocational skills, struggling with drugs and alcohol, and disabled. Few correctional facilities mitigate the educational and/or skills deficiencies of their inmates, and most inmates will return home to communities that are ill equipped to house or rehabilitate them.

A more humanistic and community-centered approach to incarceration and rehabilitation may yield more beneficial results for individuals, communities, and, ultimately, society.

Capitalism needs and must have the prison to protect itself from the [lower class] criminals it has created.

Eugene Debs (1920)

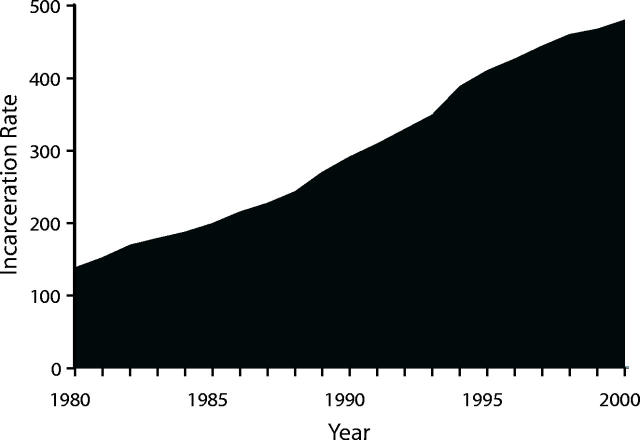

THE PRISON POPULATION IN the United States has grown significantly during the last half of the 20th century (Figure 1 ▶). Its growth is largely the result of changes in sentencing guidelines, a more punitive approach to crime reduction, and the privatization of prison-related industries and services. The prison population had fewer than 200 000 inmates in 1972; by midyear 2004, the number of inmates in US prisons had increased to almost 1 410 404,1 and an additional 713 990 inmates were held in local jails. As of 2004, 1 of every 138 Americans was incarcerated in prison or jail. 6.9 million persons are currently incarcerated or on probation or parole, an increase of more than 275% since 1980.1

FIGURE 1—

US incarceration rate per 100 000 people, by year.

Source. US Department of Justice.43

These trends have distinct consequences for public health, particularly in communities that report significant racial disparities in health. For example, US prisons increasingly house inmates who have mental disorders: it is estimated that 1 in 6 US prisoners has a mental illness.2 The incidence of serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder, is 2 to 4 times higher among prisoners than among those in the general population.3

The prevalence of infectious disease is on average 4 to 10 times greater among prisoners than among the rest of the US population, and the prevalence of chronic disease is even greater.4 In 1996, 1.3 million inmates who were released from prison had hepatitis C, 155 000 had hepatitis B, 12 000 had tuberculosis, 98 000 had HIV, and 39 000 had AIDS.5 The rapid spread of tuberculosis and HIV infection among inmates during the 1990s coincided with patterns of mass incarceration in the United States. In 1989, New York City jails and prisons were the source of 80% of all cases of a multidrug-resistant form of tuberculosis reported in the United States. By 1991, New York City’s Rikers Island facility had one of the highest rates of tuberculosis in the nation, which was largely caused by a lethal combination of prison overcrowding, lack of ventilation, and inadequate medical care.5,6

There also has been an increase in HIV prevalence among prisoners during the past decade, with the rate of infection peaking at a rate that was nearly 13 times that of the nonprison population. Women are disproportionately affected: at the end of 2002, 3% of the nation’s female state-level prison inmates were HIV positive compared with 1.9% of incarcerated males. Also in 2002, the overall rate of confirmed AIDS cases among the prison population (.48%) was nearly 3.5 times the rate among the US general population (.14%).7 Each year, many people are released from jails and prisons back into communities without knowing their HIV serostatus. Because prisons and jails often house significant concentrations of persons who have HIV/AIDS and individuals who are at great risk for acquiring HIV and/or hepatitis C via injection drug use and sexual activity, these institutions also may be venues for the transmission of infectious diseases to other prisoners and to the residents of the communities where they will return upon their release.

After their release, many ex-inmates enter open society as poorly educated individuals; they lack both vocational skills and a history of employment. Many struggle with drug and alcohol abuse and physical and/or mental disabilities.8 Ideally, the prison system would have taken on the challenge of rehabilitating inmates and improving their health. However, most prisons lack programs for educating inmates, improving their job skills, or treating problems with substance abuse. Hence, institutions and programs in the community are forced to manage the unmet problems of returning inmates.

Retributive Drug Policies

The availability and the use of illicit drugs during the last half of the 20th century account for many of the changes in prison populations and sentencing policies. During the 1960s, there was a wave of heroin abuse in many urban neighborhoods. This was followed by increases in cocaine use during the 1970s and the crack cocaine epidemic during the late 1980s. These drug epidemics contributed significantly to the prison populations of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Drug policies have had a severe impact on the federal prison system, with drug-related offenses comprising 74% of the increase in prison populations between 1985 and 1995.9 In 2000, 81% of those sentenced to state prisons were convicted of nonviolent crimes, including drug offenses (35%) and property offenses (28%).1

Lack of Opportunities Compounded by Stigma

Once released from prison, ex-offenders—the majority of whom were convicted of nonviolent offenses—face new challenges. They are “largely uneducated, unskilled, and usually without solid family supports—and now they have the added stigma of a prison record and the distrust and fear that it inevitably elicits.”8(p3) Moreover, many newly released ex-offenders return to urban core areas where they are likely to be exposed to drug sales, drug use, and other criminal activities. In many of these communities, doing time has become a rite of passage that has made imprisonment seem like a commonplace life activity, particularly among young men. Our urban core areas contain a “growing number of men, mostly non-White, who become unskilled petty criminals because of no avenues to a viable, satisfying, conventional life.”8(p46)

As local and state governments decreased spending on public health, employment, and education programs for the poor, the monies allocated for the construction and maintenance of jails and prisons increased. During the 1990s, federal spending on employment and training programs was cut nearly in half, and spending on correctional facilities increased by 521%.10 The costs of the 25-year prison buildup, in both fiscal and human terms, have been substantial, with corrections spending now approaching $60 billion a year nationally.11 By contrast, programs designed to increase the employment, housing, education, and healthcare opportunities for the urban poor have not enjoyed similar levels of funding. Arguably, adequate funding for these programs might have had a greater impact on crime and fewer negative effects on the community than massive extended incarceration of community residents.12 Consequently, the nation’s prisons are now responsible for a very large number of individuals who, in other years, would have been clients of social service agencies, students participating in educational programs, or patients in mental health facilities.

Longer prison terms with more punitive outcomes do not produce safer and healthier communities and often hinder successful reintegration of returning inmates. Less costly and more productive alternatives to incarceration have proven to be more effective sanctions, especially when dealing with nonvio-lent offenses.13 The process of imprisonment has a negative impact on the individual, the individual’s family, and the community at large.

Racial and Class Bias in the Criminal Justice System

The high rates of incarceration among people of color in the United States may contribute significantly to racial disparities in health, particularly given the high rates of mental illness and infectious disease in the nation’s jails and prisons. At the end of the 20th century, race/ethnicity, crime, and the criminal justice system were strongly associated with each other (Table 1 ▶). Nationally, 50% of all prison inmates are Black and 17% are Hispanic, proportions that differ significantly from their proportions within the general population. In 1926, Black offenders represented 21% of prison inmates; by 1954, Blacks represented 30% of inmates in state or federal prisons, and by 1988, Blacks represented half of all prison admissions.5 At midyear 2003, among males aged 25 to 29 years, 1 in 8 (12.8%) were Black, 1 in 27 (3.7%) were His-panic, and 1 in 63 (1.6%) were White.1

TABLE 1—

General Population Compared With Prison Population, by Race/Ethnicity: 2000

| General Population, % | Prison Population, % | |

| White | 70 | 35 |

| Black | 12 | 47 |

| Hispanic | 13 | 16 |

| Asian | 4 | 1 |

| Native American | 1 | 1 |

Source. US Department of Justice.44

The mass incarceration of people of color represents, as Wacquant suggests, an important shift in the nation’s struggles with the question of race and poverty. “The glaring and growing ‘disproportionality’ in incarceration that has afflicted African-Americans over the past three decades can be understood as the result of the ‘extra-penological’ functions that the prison system has come to shoulder in the wake of the crisis of the ghetto and of the continuing stigma that afflicts the descendants of slaves by virtue of their membership in a group constitutively deprived of ethnic honour.”14(p42) Additionally, there is a strong association between social class and incarceration; approximately 80% of people admitted to prison in 2002 could not afford an attorney.15 A 1991 survey of state inmates conducted by the US Department of Justice found that 65% of prisoners had not completed high school, 53% earned less than $10 000 during the year before their incarceration, and nearly 50% were either unemployed or were working part-time before their arrest.5 Hence, “Many states are not meeting their constitutional, ethical, and professional obligations to provide fair and equal treatment to poor people accused of crimes.”16(p19)

Displacement Through Imprisonment

Adaptation to modern prison life has a distinct impact on the psychological health of many incarcerated people.17 The harshness of the prison environment affects many inmates physically and emotionally and further exacerbates the psychosocial conditions of inmates who have pre-existing mental illnesses.18 The daily routine of prison life may be one of boredom and idleness compounded by problems of overcrowding. Penal institutions are often not well maintained and frequently have limited educational and recreational facilities. Numerous human rights violations—staff brutality, unhealthy and unsafe living conditions, and lack of adequate healthcare—have been documented throughout US prisons.19

The Black and Latino inner-city residents who enter the correctional system are often displaced from their communities and transferred to remote locations, which shifts political and economic capital from inner-city communities to predominantly White, exurban communities. Once there, inmates are counted in the national census as residents of those communities, a practice that results in increased federal aid and grants for the prison communities and decreased subsidies for the urban areas. Additionally, because prisoners earn little or no money, their presence in the census reduces average income rates, which makes prison communities eligible for federal housing funds. Also, census figures are used to redraw political boundaries; therefore, the prisoners’ presence helps boost the political clout of prison communities.20 Thus, communities whose residents are living in poverty and who are poorly educated are doubly deprived when the loss of their residents produces substantial economic and political gain for communities far away. The burden created by this loss of political representation and potential funding is exacerbated by further resource constraints that are created when inmates return to their communities, where the resources to meet inmates’ medical, educational, social, and economic needs are often lacking.

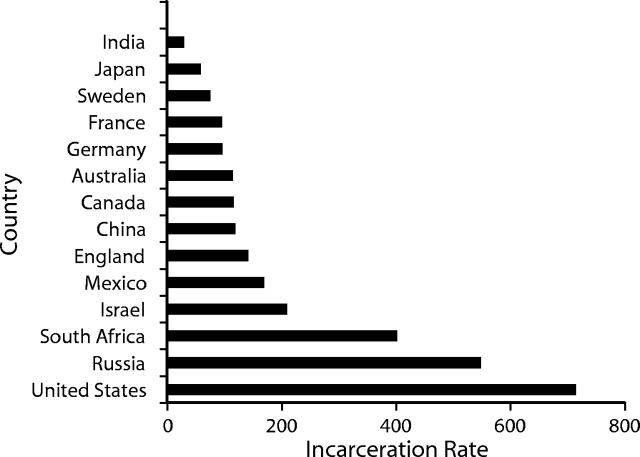

Paul Street coined the term “correctional Keynesianism” to describe the increase in construction of new prisons that are supported in large measure by increases in revenues associated with having more prisoners and greater profits from their labor. Additionally, more than 600 000 prison and jail guards and other personnel represent a potentially powerful political opposition to any scaling down of the system.20 More than half of the prisons in use today were constructed during the last 20 years.5 The rate of incarceration in the United States in 2003 was 714 inmates per 100 000 population, the highest reported rate in the world (Figure 2 ▶). Despite the fact that Canadian and Western European policymakers prefer prevention and rehabilitation through more social democratic processes, the US prison industrial complex has been transferred elsewhere as a model worthy of copying. The prison privatization movement has been exported to Australia and the United Kingdom mainly through lobbying by some international companies, a trend that raises significant issues about the ethics of imprisoning human beings in order to generate profits.9

FIGURE 2—

Comparative international rates of incarceration (numbers of people in prison per 100,000 population), 2003.

Source. International Centre for Prison Studies.21

OBSTACLES HINDERING THE REENTRY PROCESS

The US Department of Justice estimated that nearly 635 000 people were released from prison in 2002. It also estimated that 95% of the 1.4 million current prison inmates will eventually be released.22 Numerous challenges face ex-offenders and the communities that they reenter. Those ex-offenders who lack assistance from family, friends, or community-based organizations have a greater incentive to participate in criminal activity for survival and have an increased chance of being admitted to hospitals or psychiatric wards.20 Work and treatment program participation both in prison and out of prison have declined significantly during the past decade, and various legal and practical impediments limit the success of inmates who try to adapt and adjust to life after prison. The scarcity of rehabilitative programs is largely the result of (1) public antipathy to these programs, (2) the belief that these programs do not work, (3) the overall popularity of punitive measures associated with the public’s fear of crime, and (4) restrictions and misallo-cations of prison budgets. In New York, only 6% of the state’s corrections budget was spent on prisoner rehabilitation in 2000,23 despite the fact that “the relationship between participating in prison programs and reduced recidivism has been repeatedly documented.”4(p6)

Significantly, the parole system has become largely supervisory and offers few supportive services or links to healthcare, even during the earliest stages of reentry when the risk for recidivism is highest. A “new parole model should commit to a community-centered approach to parole supervision and should . . . deliver intensive treatment to substance abusers, and establish intermediate sanctions for parole violators.”4(p193)

Invisible Punishment

It is increasingly difficult for ex-offenders to return home to their communities. In most states, prisoners have their voting rights revoked while in prison, and they face a range of political and legal obstacles once they reenter open society. Other criminal sanctions that significantly reduce the rights and privileges of citizenship and legal residency comprise an “invisible punishment” with far-reaching consequences.24 Fourteen states permanently deny convicted felons the right to vote, 19 states allow the termination of parental rights, 29 states establish a felony conviction as grounds for divorce, and 25 states restrict the rights of ex-offenders to hold political office. Lawful permanent residents who are convicted of a felony risk being deported. Moreover, there is widespread refusal of federal benefits, including denial of access to student loans, revocation of drivers’ licenses, and bans on welfare, food stamp, and public housing eligibility.18

The returning prisoner’s search for permanent, sustainable housing is a daunting challenge—one that portends success or failure for the entire reintegration process. . . . Housing is the linchpin that holds the reintegration process together. Without a stable residence, continuity in substance abuse and mental health treatment is compromised. Employment is often contingent upon a fixed living arrangement. And, in the end, a polity that does not concern itself with the housing needs of returning prisoners finds that it has done so at the expense of its own public safety.25(p2)

Despite the fact that the quality and accessibility of housing has an impact on health, very little is known about the housing arrangements of former prisoners.26,27 The Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that 12% of US prisoners were homeless immediately before their incarceration.22 In 2002, Time magazine reported, “30% to 50% of big-city parolees are homeless.”28 In January 2004, New York City’s Department of Homeless Services reported that more than 30% of single adults who entered shelters were recently released from correctional institutions.29

Many of these individuals continually cycle between incarceration and shelters. For example, prisoners who serve time in upstate New York are far removed from their return destination in New York City and consequently do not have the opportunity to locate and secure housing before they are released. Some parole conditions limit the parolee’s ability to live apart from others who are participating in criminal activity. Such restrictions may preclude living with family and friends who offer shelter, which further depletes housing options. Moreover, federal regulations allow the Public Housing Authority to prohibit admission to individuals who have engaged in criminal activity.30 These restrictions, combined with the fact that the inventory of public housing continues to shrink, mean that parolees are seldom allowed to live in public housing. Lack of housing tenure has an impact on recidivism rates, and some criminologists suggest that there are greater consequences because parolees’ state of homelessness may ultimately have an impact on the community’s overall crime rate.31 Moreover, this situation creates a sense of displacement for many ex-inmates, who report feelings of alienation and despair that further disconnects them, and those who are marginalized, from any collectivist framework that fosters a sense of community and well-being.32

NEIGHBORHOOD EFFECTS AND SOCIAL CONSEQUENCES

The social characteristics of neighborhoods, for example, the rates of those living at the poverty level or below, and residential instability influence both perceived and actual levels of crime, public safety, and public health. W. J. Wilson cited evidence that when communities are forced to accommodate more ex-inmates than their social networks and systems can support, community norms begin to change, disorder and incivility increase, citizens move out of the area, and crime and violence rates rise.33 Some theorists contend that crime often becomes worse when people are afraid to go out on streets defaced by graffiti or frequented by transients and loitering youths. James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling described this phenomenon by demonstrating an association between crime rates and the number of broken windows in the community that remain unrepaired. These broken windows may indicate a lack of interest in maintaining clean, safe neighborhoods, and it may be the neighborhoods that have high rates of broken windows that are most likely to have high rates of graffiti, panhandling, poor health outcomes, and, ultimately, crime.26,34

Returning prisoners affect and are affected by this deterioration of community life. For example, a transfer of moral authority may occur in which “street smart” young men, for whom drugs and crime are a way of life, are vested with great power and influence. Those paradigms of power and oppression associated with the prison apparatus are brought to the street where “family caretakers and role models disappear or decline in influence, and as unemployment and poverty become more persistent, the community, particularly its children, become vulnerable to a variety of social ills including crime, drugs, family disorganization, generalized demoralization and unemployment.”29(p4) Furthermore, the experiential association between the structural violence of inequality and the overt violence on the street has a negative impact on both individual and collective-health outcomes.

Public safety is a top concern in communities where there are high rates of crime.35 Therefore, it is not immediately obvious that communities want all offenders to return to the places they lived before their incarceration. The key to mitigating these public perceptions is including community members in the rehabilitation process that must begin when an ex-inmate enters (or reenters) a community. Civic organizations, religious entities, health clinics, and community-based organizations all must play a role in assisting an ex-offender’s reintegration into open society and in quelling many common misconceptions about the reentry process.

Both informal and formal social control mechanisms may serve as avenues toward reducing recidivism. “Ideally, formal criminal justice sanctions should act as presses to increase social bonds to conventional institutions (e.g., work, family, school).”4(p202) Informal social controls form the structure of interpersonal bonds that link individuals to social institutions, and adult social ties are important to the degree that they create obligations and restraints that impose significant penalties for criminal deviance.36

Prisoner reentry has an impact on the production and the circulation of social capital, which can be defined in 2 ways. First, social capital depends on the degree to which an individual is embedded in social networks that can bring about the rewards and benefits that can enhance his or her life. In this instance, social capital may be viewed as a precursor to securing other forms of capital, such as information, money, or social standing. Second, social capital has been identified as the package of norms and sanctions maintained by groups so that positive or desired outcomes occur for all members, especially those outcomes that no single member could achieve on his or her own. In addition, reentry also influences the health of returning inmates and their home communities, and the collective efficacy, i.e., the capacity of community residents to make decisions and then act together to solve the problems associated with neighborhood life. Significant numbers of returning prisoners will have an “impact on families and other neighborhood collectives and institutions, in neighborhoods that experience concentrated levels of reentry.”37(p183) Coercive mobility, which is the dual process of incarceration and reentry, disrupts the social networks that are the basis of informal social control. Concentrated levels of coercive mobility can lead to diminished levels of collective efficacy and social capital, which are inexorably associated with creating a social foundation for good public health.38 Some core urban areas deserve special attention because communities that receive a massively disproportionate share of the reentry population are ill-equipped to receive them.39 Efforts to bolster and support community organizations, health clinics, and social service agencies are necessary so that these communities can better absorb inmates during the reentry process.

Although considering incarceration and reentry as a neighborhood phenomenon is relatively new, it is difficult to estimate how and to what degree residential instability leads to decreased community stability and how increased incarceration rates among community members lead to decreased levels of collective efficacy.40,41 There is no single pattern of reintegration, because each distinct neighborhood faces a unique set of challenges that depend on the population count, demographic distributions, and health needs of residents who have been incarcerated.

Freudenberg suggested that a public health agenda for action consist of the following 4 goals: improve health and social services for inmates, emphasize community reintegration for released inmates, support research and evaluation, and support alternatives to incarceration.42

CONCLUSION

The imprisonment and reentry system is in need of major reform at various levels. The current correction system is arguably iatrogenic, i.e., it is a system that causes more problems than it solves.8 A more humanistic approach to incarceration and rehabilitation that is community centered and that seeks to increase the collective efficacy of neighborhoods may well yield more beneficial results for individuals, communities, and ultimately, society as a whole. Public health professionals can play a role throughout the incarceration and reentry process by working toward healthier outcomes for both ex-offenders and the communities to which they return.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Mindy Thompson Fullilove and Mary North-ridge for their guidance and support. We also thank the good people of the Fortune Society for their vision and their commitment to social justice.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was necessary.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors The authors jointly originated and wrote the article.

References

- 1.The Sentencing Project. Facts about prisons and prisoners; November 2004. Available at: http://www.sen-tencingproject.org/pubs_02.cfm. Accessed January 1, 2005.

- 2.Human Rights Watch. Ill-equipped: US prisons and offenders with mental illness; September 2003. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/usa1003. Accessed January 1, 2005.

- 3.Hammett T, Roberts C, Kennedy S. Health-related issues in prisoner reentry. Crime Delinquency. 2000;47:390–409. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urban Institute. The public health dimensions of prisoner reentry: addressing the health needs and risks of returning prisoners and their families. Meeting Summary: the National Reentry Roundtable Meeting; December 11–12, 2002, Los Angeles, Calif.

- 5.Butterfield F. Infections in newly released inmates are rising concern. New York Times. January 28, 2003:A6.

- 6.Farmer P. Cruel and unusual: drug-resistant tuberculosis as punishment. In: Stern V, Jones R, eds. Sentenced to Die? The Problem of TB in Prisons in East and Central Europe and Central Asia. London, UK: Penal Reform International; 1999:53–74.

- 7.US Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. HIV in prisons and jails. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/abstract/hivpj02.htm. Accessed January 1, 2005.

- 8.Petersilia Joan. Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- 9.Mauer M. Race to Incarcerate. New York, NY: WW Norton and Company; 1999.

- 10.National Conference of State Legislatures. NCLS News. Medicaid, pharmaceuticals, top health priorities states say. December 12, 2002. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/programs/press/2002/pr021212.htm. Accessed April 1, 2005.

- 11.Bauer L. Justice Expenditure and Employment in the United States. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2002.

- 12.Cole D. The paradox of race and crime: a comment on Randall Kennedy’s politics of distinction.” Georgetown Law J. 1995;83: 2568–2569. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissman M, Wolf E. Revising federal sentencing policy: some consequences of expanding eligibility for alternative sanctions. Crime Delinquency. 1996;42:192–205. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wacquant L. From slavery to mass incarceration: rethinking the race question in the United States. New Left Review. 2003;13:40–61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winslow G. Capital crimes. In: Herivel T, Wright P, eds. Prison Nation: The Warehousing of America’s poor. New York, NY: Routledge; 2003:41–57.

- 16.Bright S. The accused get what the system doesn’t pay for. In: Herivel T, Wright P, eds. Prison Nation: The Warehousing of America’s Poor. New York, NY: Routledge; 2003:6–23.

- 17.Travis J, Waul M. Prisoners Once Removed: The Impact of Incarceration and Reentry on Children, Families, and Communities. Washington DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003.

- 18.Haney C. The Psychological Impact of Incarceration: Implications for Post-Prison Adjustment. Washington DC: Urban Institute Press; 2002.

- 19.Human Rights Watch. Prisoners. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/prisons. Accessed January 1, 2005.

- 20.Elsner A. Gates of Injustice. New York, NY: Financial Times Prentice Hall; 2004.

- 21.International Centre for Prison Studies. World prison population list; Febru-ary 2005. Available at: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/depsta/rel/icps/world-prison-population-list-2005.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2005.

- 22.US Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pandp.htm. Accessed January 1, 2005.

- 23.Ostreicher L. When prisoners come home. Gotham Gazette. January 2003. Available at: http://www.gothamgazette.com/article/20030117/15/187. Accessed January 1, 2005.

- 24.Travis J. Invisible punishment: an instrument of social exclusion. In: Mauer M, Chesney-Lind M, eds, Invisible Punishment: The Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment. New York, NY: The New Press; 2002:15–37.

- 25.Bradley K, Oliver RB, Richardson N, Slayter E. . No Place Like Home: Housing and the Ex-Prisoner. Boston, MA: Community Resources for Justice; 2001.

- 26.Fullilove M, Fullilove R. What’s housing got to do with it? Am J Public Health. 2000;90:183–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moloughney B. Housing and Population Health: The State of Current Research Knowledge. Toronto, ON: Cana-dian Population Health Initiative; 2004.

- 28.Ripley A. Outside the gates. TIME. January 21, 2002:66–72.

- 29.NYC Department of Homeless Services. Summary of DOC/DHS Data Match. Draft of data analysis submitted for review as part of the NYC DOC and DHS Planning Initiative, January 22, 2004.

- 30.Legal Action Center. After prison: roadblocks to reentry. A report on state legal barriers facing people with criminal records. Available at: http://www.lac.org/lac/main.php?view=profile&subaction1=NY. Accessed January 1, 2005.

- 31.Anderson E. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence and the Moral Life of the Inner City. New York, NY: Norton; 1999.

- 32.Fullilove M. Psychiatric implications of displacement: contributions from the psychology of place. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1516–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson WJ The Truly Disadvantaged. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press; 1987.

- 34.Mackenzie D L. Sentencing and corrections in the 21st century: setting the stage for the future. National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 2000. Available at: www.ncjrs.org/pdffiles1/nij/189106-2.pdf. Accessed January 1, 2005.

- 35.Anderson A, Milligan S. Social Capital and Community Building. Cleve-land OH: Case Western Reserve University; 2001.

- 36.Laub J, Sampson R. Understanding Desistance from Crime. Crime Justice. 2001;28:1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose T, Clear T. Incarceration, Reentry and Social Capital: Social Networks in the Balance. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2002.

- 38.Fullilove M. Promoting social cohesion to improve health. J Am Med Women’s Assoc. 1998:53:72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.La Vigne N, Mamalian C, Travis J, Visher C. A Portrait of Prisoner Re-Entry in Illinois. Washington DC: Urban Institute; 2003.

- 40.Sampson R, Raudenbush R. Systematic Social observations of public spaces: a new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol. 1999;105: 603–651. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fullilove M. Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts Amer-ica, and What We Can Do About It. New York, NY: One World/Ballantine Books; 2004.

- 42.Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health. 2001;78:214–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.US Bureau of the Census. Bulletin: Prisoners in 2000. Washington, DC; US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2001. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed April 1, 2005.

- 44.Incarceration Rate. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/glance/tables/incrttab.htm. Accessed April 1, 2005.