Abstract

Objectives. We sought to provide estimates of disability prevalence for states and metropolitan areas in the United States.

Methods. We analyzed Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data from 2001 for all 50 states and the District of Columbia and 103 metropolitan areas. We performed stratified analyses by demographics for 20 metropolitan areas with the highest prevalence of disability.

Results. State disability estimates ranged from 10.5% in Hawaii to 25.9% in Arizona. Metropolitan disability estimates ranged from 10.2% in Honolulu, Hawaii to 27.1% in Tucson, Ariz. Regional metropolitan medians for disability (range, 17.0–19.7%) were similar across the Northeast, Midwest, and South and were highest in the West. In the 20 metropolitan areas with the highest disability estimates, the prevalence of disability generally increased with age and was higher for women and those with a high-school education or less.

Conclusions. State and metropolitan-area estimates may be used to guide state and local efforts to prevent, delay, or reduce disability and secondary conditions in persons with disabilities.

In 2000, disability affected an estimated 49.7 million persons in the United States,1 and direct medical costs for persons with disability were $260 billion in 1996.2 As the population ages and the prevalence of disability increases, annual disability-related costs to the US health care system can be expected to rise, with more than 56% paid by the US government.3

Development of health promotion policies and disease prevention programs relating to people with disability would be aided by public health surveillance, but the lack of a brief case definition of disability has hindered efforts to obtain state and local estimates of the prevalence of this problem. One of the national objectives of Healthy People 2010, published in 2000, is to “include in the core of all Healthy People 2010 surveillance instruments a standardized set of questions that identify ‘people with disabilities.’ ”4 In 2001, 2 core questions were added to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to identify people with disabilities in all of the states that use the survey—one relating to activity limitation and the other to special equipment.5–7 The BRFSS has a sufficiently large sample (more than 200 000) to allow analyses of disability data at the metropolitan level.

We used 2001 BRFSS data to examine disability in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and 103 metropolitan areas. The purposes of our study were to estimate the prevalence of disability at the state and metropolitan levels and to compare disability estimates by age, gender, race/ethnicity, and educational level for the 20 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) with the highest prevalence of disability.

METHODS

The BRFSS is a state-based surveillance system operated by state health departments in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Briefly, the surveillance system collects data on many of the behaviors and conditions that place adults (aged 18 years or more) at risk for chronic disease. Trained interviewers used an independent probability sample of households with telephones to collect data on a monthly basis among the noninstitutionalized US population. In 2001, BRFSS was conducted in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands (n = 212, 510). A detailed description of the survey methods is available elsewhere.8,9 All BRFSS questionnaires and data are available on the Internet at www.cdc.gov/brfss.

Disability Definition

Persons with a disability were defined as respondents who answered “yes” to 1 of 2 questions: “are you limited in any way in any activities because of physical, mental, or emotional problems?” and “do you now have any health problem that requires you to use special equipment, such as a cane, wheelchair, special bed, or special telephone?” Persons for whom responses to both questions were missing, “don’t know,” or “refused” were excluded from the analysis.

Metropolitan Areas

Self-reported county of residence was used to classify respondents as residents of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), primary MSAs (PMSAs), or New England county metropolitan areas (NECMAs) on the basis of standard definitions from the US Bureau of the Census.10 All counties within the MSA, PMSA, or NECMA were included for metropolitan areas that crossed state boundaries. Here, the term MSA refers to PMSAs, NECMAs, or MSAs. Data were reweighted to each MSA on the basis of age, gender, and race/ethnicity, a methodology similar to that used in weighting BRFSS state data.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS11 and SUDAAN.12 SUDAAN was used to account for the complex survey design and to determine the standard errors and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Estimates of disability prevalence in individual states were on the basis of data from all state respondents, including persons who lived within MSAs. State samples ranged from 1888 (District of Columbia) to 8628 (Massachusetts), and MSA samples ranged from 303 (Oakland, Calif) to 8694 (Boston–Worcester–Lawrence–Lowell–Brockton, Mass, NH). We did not age-adjust the data, because we wanted to provide actual disability estimates for each state and MSA.

To improve precision of the MSA estimates, analyses were limited to MSAs with a large-enough sample to be reweighted. Of 324 MSAs, 103 met our inclusion criteria. Data were available from MSAs in 47 states (Alaska, Montana, and New Hampshire are not represented) and the District of Columbia. MSAs were grouped by census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and regional median and range values for disability were calculated. For the 20 MSAs with the highest levels of disability, we conducted analyses of disability estimates stratified by age (18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years of age), gender, race/ethnicity (White, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic), and education level (high school or less; more than high school). Because of small numbers, analyses were conducted only for subpopulations with 50 or more respondents. For these 20 MSAs, we used 2-sample t tests for differences between estimates to assess differences between subgroups within each area. Because of the potential problem of multiple comparisons, differences were considered significant only when P < .01. To permit comparisons across these 20 areas, unconditional logistic regression analysis was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for potential confounders (age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity).

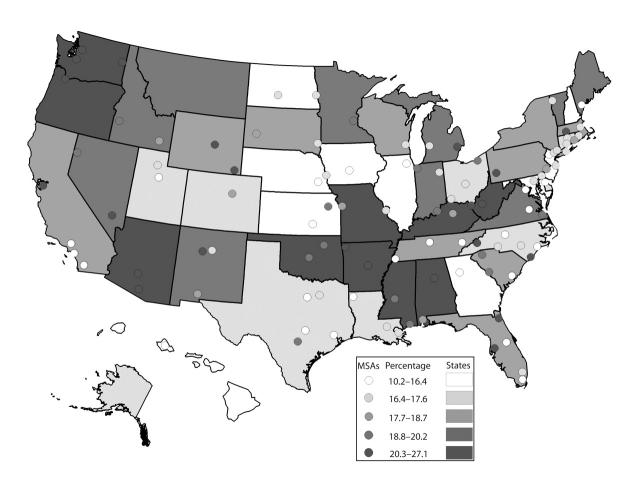

We developed a map to portray the prevalence of disability by state and MSA; cut points for both measures on the map were based on quintile ranges. ArcGIS 8.2 geographic information system software13 was used to create the map.

RESULTS

Estimates for the prevalence of disability for the 50 states and the District of Columbia are listed in Table 1 ▶ and mapped in Figure 1 ▶. State disability estimates ranged from 10.5% in Hawaii to 25.9% in Arizona (median, 18.0%). Seven states had disability estimates greater than 22% (Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Kentucky, Oregon, Washington, and West Virginia).

TABLE 1—

Unadjusted Prevalence of Disability Among Adults in the United States, by State: 2001

| Percentage Disabled (95% CI) | |

| Alabama | 22.1 (20.4, 23.8) |

| Alaska | 16.7 (14.8, 18.6) |

| Arizona | 25.9 (23.7, 28.1) |

| Arkansas | 22.0 (20.4, 23.7) |

| California | 17.8 (16.4, 19.2) |

| Colorado | 17.1 (15.3, 18.9) |

| Connecticut | 16.7 (15.7, 17.6) |

| Delaware | 16.6 (15.1, 18.2) |

| District of Columbia | 14.8 (12.9, 16.8) |

| Florida | 18.6 (17.3, 19.9) |

| Georgia | 15.5 (14.3, 16.7) |

| Hawaii | 10.5 (9.3, 11.7) |

| Idaho | 19.8 (18.5, 21.1) |

| Illinois | 16.2 (14.5, 18.0) |

| Indiana | 18.9 (17.6, 20.3) |

| Iowa | 15.9 (14.6, 17.2) |

| Kansas | 16.2 (15.0, 17.4) |

| Kentucky | 23.8 (22.5, 25.1) |

| Louisiana | 17.0 (15.9, 18.2) |

| Maine | 20.0 (18.3, 21.7) |

| Maryland | 15.9 (14.5, 17.3) |

| Massachusetts | 18.0 (17.0, 18.9) |

| Michigan | 19.6 (18.2, 21.0) |

| Minnesota | 19.0 (17.7, 20.4) |

| Mississippi | 21.0 (19.3, 22.6) |

| Missouri | 20.2 (18.6, 21.8) |

| Montana | 20.2 (18.3, 22.0) |

| Nebraska | 16.4 (15.0, 17.7) |

| Nevada | 20.0 (17.8, 22.2) |

| New Hampshire | 15.8 (14.6, 17.0) |

| New Jersey | 15.8 (14.6, 17.0) |

| New Mexico | 19.5 (18.0, 21.0) |

| New York | 17.8 (16.3, 19.2) |

| North Carolina | 17.1 (15.6, 18.5) |

| North Dakota | 15.5 (14.0, 17.0) |

| Ohio | 17.6 (16.1, 19.0) |

| Oklahoma | 21.2 (19.8, 22.7) |

| Oregon | 23.3 (21.5, 25.1) |

| Pennsylvania | 18.7 (17.3, 20.1) |

| Rhode Island | 17.0 (15.6, 18.3) |

| South Carolina | 17.8 (16.3, 19.3) |

| South Dakota | 18.2 (17.1, 19.4) |

| Tennessee | 17.8 (16.1, 19.4) |

| Texas | 16.6 (15.6, 17.7) |

| Utah | 17.3 (15.7, 18.8) |

| Vermont | 18.9 (17.6, 20.2) |

| Virginia | 18.7 (17.2, 20.3) |

| Washington | 22.7 (21.3, 24.1) |

| West Virginia | 25.7 (24.0, 27.3) |

| Wisconsin | 18.4 (16.9, 19.9) |

| Wyoming | 18.1 (16.6, 19.6) |

| Nationwide median | 18.0 |

| Range | 10.5–25.9 |

FIGURE 1—

Unadjusted prevalence of disability by state and metropolitan statistical area (MSA), 2001.

Estimates for the prevalence of disability for the 103 MSAs are listed in Table 2 ▶ and mapped in Figure 1 ▶. Regional medians for disability (range, 17.0–19.7%) were similar across the Northeast, Midwest, and South and highest in the West. Within the West, there was more than a 150% difference in the prevalence of disability (from 10.2% in Honolulu, Hawaii to 27.1% in Tucson, Ariz). Ten MSAs had disability estimates greater than 22%. The variation among the MSAs was generally higher than that among states.

TABLE 2—

Unadjusted Prevalence of Disability Among Adults in the United States, by Region and MSA: 2001

| Percentage Disabled (95% CI) | |

| Northeast | |

| Bergen–Passaic, NJ | 16.9 (13.8, 20.1) |

| Boston–Worcester–Lawrence– Lowell–Brockton, Mass, NH | 17.6 (16.6, 18.5) |

| Burlington, VT | 17.4 (15.1, 19.6) |

| Hartford, CT | 16.5 (14.9, 18.1) |

| Monmouth–Ocean, NJ | 16.6 (13.2, 20.1) |

| Nassau–Suffolk, NY | 16.9 (13.2, 20.6) |

| New Haven–Bridgeport–Stamford– Waterbury–Danbury, CT | 16.6 (15.0, 18.1) |

| New London–Norwich, CT | 18.5 (15.1, 21.9) |

| New York, NY | 17.0 (14.6, 19.4) |

| Newark, NJ | 14.6 (12.2, 16.9) |

| Philadelphia, Pa, NJ | 17.6 (15.4, 19.8) |

| Pittsburgh, Pa | 21.8 (18.1, 25.5) |

| Portland, Me | 16.3 (12.9, 19.8) |

| Providence–Warwick–Pawtucket, RI | 17.1 (15.6, 18.5) |

| Springfield, MA | 20.4 (17.2, 23.5) |

| Northeast median | 17.0 |

| Range | 14.6–21.8 |

| Midwest | |

| Bismarck, ND | 16.5 (12.4, 20.6) |

| Chicago, IL | 15.5 (13.3, 17.6) |

| Cincinnati, Ohio, Ky, Ind | 17.6 (14.8, 20.4) |

| Cleveland–Lorain–Elyria, Ohio | 19.1 (15.4, 22.8) |

| Columbus, Ohio | 16.5 (12.7, 20.2) |

| Des Moines, Iowa | 12.5 (9.8, 15.2) |

| Detroit, Mich | 20.4 (18.0, 22.8) |

| Fargo–Moorhead, ND, Minn | 17.5 (12.3, 22.6) |

| Fort Wayne, Ind | 17.6 (13.2, 21.9) |

| Gary, Ind | 19.3 (15.0, 23.6) |

| Grand Rapids–Muskegon– Holland, Mich | 17.4 (13.8, 21.1) |

| Kansas City, Mo, Kan | 18.2 (16.0, 20.4) |

| Lincoln, Neb | 13.0 (10.2, 15.8) |

| Milwaukee–Waukesha, Wis | 17.2 (14.4, 19.9) |

| Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minn, Wis | 18.9 (17.0, 20.7) |

| Omaha, Neb, Iowa | 17.3 (15.0, 19.5) |

| Rapid City, SD | 18.1 (14.6, 21.6) |

| St. Louis, Mo, Ill | 17.3 (14.2, 20.4) |

| Sioux Falls, SD | 17.4 (15.1, 19.7) |

| Topeka, Kan | 18.8 (14.1, 23.6) |

| Wichita, Kan | 15.6 (12.9, 18.2) |

| Midwest median | 17.4 |

| Range | 12.5–20.4 |

| South | |

| Asheville, NC | 20.5 (15.9, 25.2) |

| Atlanta, Ga | 12.7 (10.8, 14.6) |

| Augusta–Aiken, Ga, SC | 19.0 (14.2, 23.8) |

| Austin–San Marcos, Tex | 15.0 (11.1, 19.0) |

| Baltimore, Md | 17.5 (15.3, 19.7) |

| Baton Rouge, La | 17.1 (13.7, 20.4) |

| Biloxi–Gulfport–Pascagoula, Miss | 19.5 (14.9, 24.2) |

| Birmingham, Ala | 23.4 (19.5, 27.4) |

| Charleston–North Charleston, SC | 14.6 (11.0, 18.2) |

| Charleston, WVa | 23.7 (19.5, 27.9) |

| Charlotte–Gastonia– Rock Hill, NC, SC | 17.0 (13.5, 20.5) |

| Dallas, Tex | 17.1 (14.4, 19.9) |

| Dover, Del | 14.2 (12.0, 16.4) |

| Fayetteville, NC | 16.9 (12.7, 21.0) |

| Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers,Ark | 21.0 (16.1, 26.0) |

| Fort Lauderdale, Fla | 17.1 (12.8, 21.5) |

| Fort Worth–Arlington, Tex | 15.4 (11.8, 19.1) |

| Greensboro–Winston-Salem– High Point, NC | 14.8 (11.8, 17.8) |

| Greenville–Spartanburg– Anderson, SC | 19.0 (15.9, 22.1) |

| Houston, Tex | 13.0 (10.8, 15.1) |

| Huntington–Ashland,WVa, Ky, Ohio | 24.8 (20.3, 29.3) |

| Jackson, Miss | 18.8 (14.9, 22.6) |

| Jacksonville, Fla | 20.7 (16.2, 25.2) |

| Jacksonville, NC | 13.9 (10.1, 17.8) |

| Knoxville, Tenn | 15.4 (11.1, 19.6) |

| Lexington, Ky | 17.7 (13.7, 21.7) |

| Little Rock–North Little Rock, Ark | 21.0 (17.5, 24.6) |

| Louisville, Ky, Ind | 20.0 (16.6, 23.5) |

| Memphis, Tenn, Ark, Miss | 16.4 (12.6, 20.1) |

| Miami, Fla | 14.6 (11.1, 18.2) |

| Mobile, Ala | 17.7 (13.4, 22.0) |

| Nashville, Tenn | 16.3 (13.1, 19.6) |

| New Orleans, La | 16.9 (14.6, 19.2) |

| Norfolk–Virginia Beach– Newport News, Va, NC | 19.7 (15.9, 23.4) |

| Oklahoma City, Okla | 18.8 (15.7, 21.9) |

| Orlando, Fla | 15.9 (11.8, 19.9) |

| Richmond–Petersburg, Va | 16.4 (12.3, 20.4) |

| San Antonio, Tex | 18.8 (14.6, 23.0) |

| Shreveport–Bossier City, La | 15.2 (11.7, 18.7) |

| Tampa–St. Petersburg– Clearwater, Fla | 21.3 (17.6, 25.1) |

| Tulsa, Okla | 19.8 (16.3, 23.3) |

| Washington, DC, Md, Va, WVa | 14.4 (12.9, 16.0) |

| Wilmington–Newark, Del, Md | 17.2 (15.0, 19.3) |

| Wilmington, NC | 23.3 (16.3, 30.4) |

| South median | 17.1 |

| Range | 12.7–24.8 |

| West | |

| Albuquerque, NM | 20.3 (17.5, 23.0) |

| Boise City, Idaho | 19.7 (17.0, 22.4) |

| Casper, Wyo | 22.0 (17.4, 26.6) |

| Cheyenne, Wyo | 20.8 (16.4, 25.3) |

| Denver, Colo | 18.1 (15.4, 20.8) |

| Honolulu, Hawaii | 10.2 (8.7, 11.7) |

| Las Cruces, NM | 18.7 (14.1, 23.3) |

| Las Vegas, Nev, Ariz | 21.0 (18.3, 23.7) |

| Los Angeles–Long Beach, Calif | 15.9 (12.9, 18.9) |

| Oakland, Calif | 22.5 (16.9, 28.1) |

| Orange County, Calif | 14.2 (10.2, 18.1) |

| Phoenix–Mesa, Ariz | 25.6 (22.3, 28.8) |

| Pocatello, Idaho | 18.0 (13.5, 22.6) |

| Portland–Vancouver, Ore, Wash | 22.8 (20.3, 25.4) |

| Provo–Orem, Utah | 15.4 (11.3, 19.4) |

| Reno, Nev | 19.3 (16.4, 22.3) |

| Salt Lake City–Ogden, Utah | 16.9 (14.7, 19.0) |

| San Diego, Calif | 14.1 (10.2, 18.0) |

| Santa Fe, NM | 17.0 (12.9, 21.0) |

| Seattle–Bellevue–Everett, Wash | 21.4 (19.4, 23.5) |

| Spokane, Wash | 26.7 (21.3, 32.2) |

| Tacoma, Wash | 20.8 (16.7, 25.0) |

| Tucson, Ariz | 27.1 (23.4, 30.8) |

| West median | 19.7 |

| Range | 10.2–27.1 |

| Nationwide median | 17.5 |

| Nationwide range | 10.2–27.1 |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

The 20 MSAs with the highest disability estimates are listed in Table 3 ▶. Ten were in the West (Arizona, California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming), 9 were in the South (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia), and 1 was in the East (Pennsylvania). Not unexpectedly, 11 of these 13 states had disability estimates exceeding the nationwide median estimate (18%). Conversely, the 7 MSAs with the lowest prevalence of disability (San Diego, Calif; Atlanta, Ga; Honolulu, Hawaii; Des Moines, Iowa; Jacksonville, NC; Lincoln, Neb; and Houston, Tex) were located in states with estimates of disability below the nationwide median.

TABLE 3—

Unadjusted Prevalence of Disability (%) Among Adults in the United States, by Age, Gender, and Education, for the 20 MSAs with the Highest Levels of Disability: 2001

| Age (95% CI) | Gender (95% CI) | Education (95% | ||||||

| MSA | n | 18–44 Years | 45–64 Years | ≥65 Years | Men | Women | High School or Less | More than High School |

| Tucson, Ariz | 710 | 21.3 (16.2, 26.4)a | 32.9 (25.6, 40.2) | 35.6 (27.5, 43.7) | 29.1 (23.2, 34.9) | 25.2 (20.6, 29.8) | 26.8 (20.4, 33.2) | 27.5 (22.8, 32.1) |

| Spokane, Wash | 306 | 17.2 (10.6, 23.8)a | 30.6 (20.0, 41.1) | 46.9 (33.4, 60.4) | 19.1 (11.6, 26.6) | 33.7 (26.2, 41.3)b | 31.9 (21.7, 42.1) | 24.0 (17.8, 30.2) |

| Phoenix–Mesa, Ariz | 1016 | 20.4 (15.8, 25.1)a | 29.6 (23.8, 35.4) | 35.2 (27.6, 42.7) | 25.3 (20.6, 30.1) | 25.8 (21.4, 30.3) | 26.5 (20.7, 32.3) | 25.0 (21.2, 28.9) |

| Huntington–Ashland, WVa, Ky, Ohio | 707 | 18.7 (12.1, 25.3) | 29.8 (21.4, 38.1) | 31.7 (22.9, 40.6) | 25.7 (18.6, 32.7) | 24.0 (18.2, 29.8) | 27.8 (21.5, 34.0) | 21.2 (14.7, 27.7) |

| Charleston, WVa | 439 | 13.2 (8.3, 18.1)a | 29.1 (21.5, 36.7) | 39.3 (28.3, 50.3) | 21.7 (15.6, 27.7) | 25.5 (19.6, 31.4) | 28.9 (22.3, 35.4) | 18.6 (13.3, 23.9) |

| Birmingham, Ala | 557 | 13.3 (8.8, 17.7)a | 31.9 (24.2, 39.7) | 40.0 (29.7, 50.3) | 20.9 (14.8, 26.9) | 25.7 (20.6, 30.8) | 29.4 (22.9, 36.0) | 18.4 (13.6, 23.3)c |

| Wilmington, NC | 424 | 21.9 (10.3, 33.5) | 21.0 (11.3, 30.7) | 30.6 (14.3, 46.9) | 17.6 (8.3, 27.0) | 28.1 (18.0, 38.2) | 36.7 (23.7, 49.7) | 15.3 (7.6, 22.9)c |

| Portland–Vancouver, Ore, Wash | 1303 | 14.0 (11.1, 16.9)a | 27.2 (22.4, 31.9)a | 43.2 (35.7, 50.7) | 20.8 (17.1, 24.5) | 24.8 (21.4, 28.2) | 22.9 (18.5, 27.2) | 22.8 (19.8, 25.9) |

| Oakland, Calif | 299 | 19.5 (12.1, 26.9) | 22.9 (12.8, 33.0) | NA | 22.4 (13.4, 31.4) | 22.6 (15.8, 29.3) | 28.7 (16.3, 41.1) | 19.9 (14.0, 25.8) |

| Casper, Wyo | 404 | 18.1 (11.6, 24.6)a | 19.6 (11.9, 27.3) | 36.8 (25.6, 48.0) | 19.5 (13.0, 26.0) | 24.3 (17.9, 30.7) | 22.0 (14.9, 29.0) | 22.0 (15.9, 28.0) |

| Pittsburgh, Pa | 682 | 15.9 (10.3, 21.6) | 28.1 (21.6, 34.6) | 24.4 (17.5, 31.4) | 20.3 (15.0, 25.6) | 23.1 (18.0, 28.2) | 22.6 (17.5, 27.7) | 21.3 (16.0, 26.5) |

| Seattle–Bellevue–Everett, Wash | 1728 | 15.3 (12.8, 17.8)a | 24.5 (20.6, 28.4)a | 37.7 (31.3, 44.0) | 19.4 (16.4, 22.3) | 23.4 (20.5, 26.3) | 25.0 (20.6, 29.4) | 20.2 (17.8, 22.5) |

| Tampa–St. Petersburg–Clearwater,Fla | 627 | 11.2 (6.8, 15.5)a | 26.1 (19.1, 33.1) | 32.8 (24.2, 41.4) | 21.1 (15.2, 27.1) | 21.5 (16.9, 26.2) | 21.8 (16.4, 27.3) | 20.1 (15.1, 25.1) |

| Little Rock–North Little Rock, Ark | 615 | 11.7 (7.7, 15.6)a | 25.6 (18.8, 32.4)a | 43.5 (33.1, 53.9) | 22.7 (16.9, 28.5) | 19.5 (15.3, 23.8) | 26.9 (21.0, 32.8) | 16.5 (12.1, 20.8)c |

| Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers, Ark | 328 | 14.7 (8.8, 20.6) | 26.1 (16.2, 36.0) | 30.6 (18.0, 43.1) | 19.9 (12.6, 27.2) | 22.1 (15.4, 28.8) | 24.0 (15.5, 32.4) | 19.1 (13.1, 25.0) |

| Las Vegas, Nev, Ariz | 1146 | 13.8 (10.4, 17.2)a | 26.2 (21.0, 31.3) | 31.9 (25.0, 38.9) | 18.5 (14.8, 22.2) | 23.5 (19.6, 27.4) | 22.6 (18.1, 27.1) | 20.0 (16.6, 23.4) |

| Cheyenne, Wyo | 470 | 18.1 (11.4, 24.8) | 19.5 (13.1, 25.9) | 33.0 (21.5, 44.5) | 22.4 (15.1, 29.7) | 19.3 (14.1, 24.5) | 24.2 (16.2, 32.1) | 18.6 (13.6, 23.6) |

| Tacoma, Wash | 430 | 10.3 (6.2, 14.3)a | 27.1 (19.2, 35.1) | 45.8 (32.0, 59.7) | 17.6 (12.0, 23.2) | 24.1 (18.0, 30.1) | 20.0 (13.1, 26.8) | 21.3 (16.1, 26.5) |

| Jacksonville, Fla | 418 | 13.3 (8.3, 18.3)a | 26.6 (17.9, 35.3) | 32.9 (19.9, 46.0) | 20.1 (13.2, 27.0) | 21.2 (15.5, 27.0) | 21.4 (14.1, 28.8) | 20.2 (14.7, 25.7) |

| Asheville, NC | 426 | 13.4 (7.2, 19.6) | 28.6 (20.7, 36.5) | 23.2 (10.9, 35.5) | 16.5 (10.0, 23.1) | 24.0 (17.5, 30.6) | 29.0 (20.7, 37.3) | 13.1 (8.6, 17.6)c |

Note. CI = confidence interval; NA = not available because of insufficient sample size.

aP < .01 for comparison with persons aged 65 years or more.

bP < .01 for comparison with men.

cP < .01 for comparison with persons with a high-school education or less.

Disability varied by age among the 20 MSAs with the highest disability estimates. Compared with persons aged 65 years or more, estimates were significantly lower in 13 MSAs among those aged 18–44 years and in 3 areas among those aged 45–64 years. Among persons aged 65 years or more, estimates ranged from 23.2% in Asheville, NC, to 46.9% in Spokane, Wash. Among adults aged 45–64 years, estimates ranged from 19.5% in Cheyenne, Wyo, to 32.9% in Tucson, Ariz. Among adults aged 18–44 years, estimates ranged from 10.3% in Tacoma, Wash to 21.9% in Wilmington, NC. In contrast, there were few significant differences in disability estimates by gender or education. Disability estimates were higher for women in 16 of 20 areas, but the difference was significant in only 1 MSA (Spokane, Wash). Disability estimates were higher for persons with a high-school education or less in 17 of 20 MSAs, but the difference was significant in only 4 MSAs (Birmingham, Ala; Little Rock–North Little Rock, Ark; and Asheville and Wilmington, NC).

Comparisons of disability by race or ethnicity (not shown) were available for Black, non-Hispanic persons in 4 MSAs and for Hispanics in 6 MSAs. Estimates were significantly higher for White, non-Hispanic persons than Black, non-Hispanic persons in 1 area (Jacksonville, Fla, 24.7% vs 7.8%, respectively) and for White, non-Hispanic persons than Hispanics in 3 areas (Tucson, Ariz, 32.3% vs 14.6%, respectively; Las Vegas, Nev, Ariz, 22.8% vs 7.0%, respectively; Portland–Vancouver, Ore, Wash, 24.7% vs 8.9%, respectively).

After adjustment for confounders, we found significantly lower AORs for disability among persons aged 18–44 years in Tacoma, Wash (compared with Phoenix–Mesa and Tucson, Ariz; Wilmington, NC; and Pittsburgh, Pa); persons aged 45–64 years in Casper, Wyo (compared with Asheville, NC); and persons aged 65 years or more in Wilmington, NC (compared with Tacoma, Wash) (not shown). A significantly higher AOR for disability among women was found in Spokane, Wash, compared with Little Rock–North Little Rock, Ark, and among persons with high-school education or less in Asheville, NC, compared with Casper, Wyo. Among metropolitan areas with 50 or more Black, non-Hispanics or Hispanics, there were no significant differences in AORs for disability.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, ours was the first study to comprehensively examine disability estimates across state and metropolitan areas. We found median metropolitan estimates by region to be similar across the Northeast, Midwest, and South and highest in the West. Even so, there were important intraregional, interregional, and interstate differences. For example, in the West, there was more than a 150% difference in disability between Honolulu, Hawaii, and Tucson, Ariz. In North Carolina, Wilmington was among the MSAs with the highest prevalence of disability, but Jacksonville, Fla, was among the lowest.

We also found important differences between subpopulations. Lower estimates among persons aged 18–44 years were not surprising.1 Rates of disability were higher among older adults, who also have higher rates of chronic diseases.14 Nonetheless, in absolute terms, most disability occurs during the working years, which contributes to the high cost of disability.15 Arthritis or rheumatism, back or spine problems, and heart trouble/hardening of the arteries continue to be the leading causes of disability.2 For differences by gender and education, men and people with higher levels of education are generally less likely to be disabled.14,16,17

Results for our top MSAs were consistent with nationally representative data from the US Bureau of the Census, demonstrating higher disability estimates as people age and among persons with lower levels of educational attainment.1,18 The US Bureau of the Census data also demonstrated that disability estimates are higher for Black, non-Hispanic persons and Hispanics than White, non-Hispanic persons.1 We did not have similar findings in this regard. White, non-Hispanic persons had a significantly higher prevalence of disability than Black, non-Hispanic persons in Jacksonville, Fla, and higher estimates than Hispanics in Tuscon, Ariz; Las Vegas, Nev, Ariz; and Portland–Vancouver, Ore, Wash. However, we had only a limited number of MSAs with adequate sample to permit such comparisons.

Our study had several limitations. Because BRFSS excludes institutionalized persons and those without telephones as well as those unable to complete the survey because of hearing or speech impairments, lack of stamina, or an inability to answer the phone, our findings almost certainly underestimate the true prevalence of disability in the United States. The BRFSS represents self-reported data; such indicators of activity limitations and compensatory strategies have not been validated as measures of disability. Furthermore, the questions used to define disability in this analysis do not account for severity of disability.

Differences by MSAs may reflect variations by age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, income, and retirement patterns. Our estimates were for entire MSAs, but disability estimates are likely to vary within each MSA as well (eg, central cities vs suburbs). In addition, the precision of our estimates varied across subpopulations, because the number of respondents was small in many areas. Sample sizes varied widely because of differences in financial support of the BRFSS by the states.19 As a result, small MSAs in some states had large samples, whereas other states had larger MSAs with smaller samples, preventing us from including some areas because of insufficient sample size.

These limitations notwithstanding, the BRFSS offers important benefits for making state and metropolitan-level population estimates because of its standardized data collection protocols and methodologies, timeliness, flexibility, and cost savings. Our results demonstrate the diversity of needs within states and local areas and provide baseline data to guide additional analyses on state and metropolitan-level disability trends. This information is invaluable for assisting state and local health officials in program planning and evaluation for state and local programs designed to prevent disabilities and secondary conditions in persons with disabilities. Furthermore, this information assists in characterizing state and MSA-specific disability patterns by means of uniform surveillance and aids in planning for funding of disability services and health-promotion activities in addition to enhancing existing programs. Given the diversity of needs within states or even within a given community, state and local health officials should take an active role in developing and enhancing existing programs to promote healthy behaviors and prevent, delay, or reduce disability.

Acknowledgments

We thank the state Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System coordinators for their help in collecting the data used in this analysis; Henry E. Wells of the Research Triangle Institute; and members of the Behavior Surveillance Branch, Division of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Peer Reviewed

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributors C. A. Okoro originated and designed the study, completed the analyses, and led the writing. J. B. Holt assisted with the geographic mapping. L. S. Balluz, V. A. Campbell, and A. H. Mokdad helped interpret the findings. All authors helped to review drafts of this article.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

References

- 1.Waldrop J, Stern SM. Disability Status: 2000. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2003. Report No. C2KBR-17. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-17.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2004.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults—United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Congressional Budget Office. Projections of Expenditures for Long-Term Care Services for the Elderly. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 1999. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdoc.cfm?index=1123&type=1. Accessed May 25, 2004.

- 4.Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- 5.Lollar DJ, Crews JE. Redefining the role of public health in disability. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24: 195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy People with Disabilities. Atlanta, GA: National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities; 2002. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/factsheets/DH_hp2010.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2005.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State-specific prevalence of disability among adults—11 states and the District of Columbia, 1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:711–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH. Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment. Recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR–9):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtzman D. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. In: Blumenthal DS, DiClemente RJ, eds. Community-Based Health Research: Issues and Methods. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2004:115–131.

- 10.Metropolitan Areas Defined. Washington, DC: Office of Management and Budget; 1993. Report No. 1990 CPH-S-1–1.

- 11.SAS. 8.02 ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2001.

- 12.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN User’s Manual. 8.0 ed. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2001.

- 13.ArcGIS 8.2. 8.2 ed. Redlands, CA: Environmental Research Systems, Inc; 2002.

- 14.Freedman VA, Martin LG, Schoeni RF. Recent trends in disability and functioning among older adults in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002; 288:3137–3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Census Bureau. 11th Anniversary of Americans with Disabilities Act (July 26). Facts for Features. July 11, 2001. Report No. CB01-FF.10. Available at: http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/2001/cb01ff10.html. Accessed May 25, 2004.

- 16.Fries JF. Reducing disability in older age. JAMA. 2002;288:3164–3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostchega Y, Harris TB, Hirsch R, Parsons VL, Kington R. The prevalence of functional limitations and disability in older persons in the US: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1132–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNeil J. Americans with Disabilities: 1997. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2001. Report No. P70–73. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/p70-73.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2004.

- 19.Nelson D, Holtzman D, Waller M. Objectives and Design of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Dallas, TX: American Statistical Association; 1998: 214–218.