Abstract

Objectives: In 1994, the US Public Health Service launched the “Back to Sleep” campaign, promoting the supine sleep position to prevent sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Studies of SIDS in the United States have generally found socioeconomic and race disparities. Our objective was to see whether the “Back to Sleep” campaign, which involves an effective, easy, and free intervention, has reduced social class inequalities in SIDS.

Methods: We conducted a population-based case-cohort study during 2 periods, 1989 to 1991 and 1996 to 1998, using the US Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Sets. Case group was infants who died of SIDS in infancy (N = 21 126); control group was a 10% random sample of infants who lived through the first year and all infants who died of other causes (N=2241218). Social class was measured by mother’s education level.

Results: There was no evidence that inequalities in SIDS were reduced after the Back to Sleep campaign. In fact, odds ratios for SIDS associated with lower social class increased between 1989–1991 and 1996–1998. The race disparity in SIDS increased after the Back to Sleep campaign.

Conclusions: The introduction of an inexpensive, easy, public health intervention has not reduced social inequalities in SIDS; in fact, the gap has widened. Although the risk of SIDS has been reduced for all social class groups, women who are more educated have experienced the greatest decline.

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the leading cause of postneonatal infant mortality in the United States.1 During the 1990s, there was a dramatic decline in these deaths after the recognition of a causal role for infant sleep position and the implementation of public health policy initiatives to promote supine sleep position. The American Academy of Pediatrics agreed and adopted recommendations on sleep position in 1992,2 followed in 1994 by the launch of the United States Public Health Service “Back to Sleep” campaign.3 Consequently, the SIDS rate dropped from 1.3 per 1000 live births in 1990 to 0.7 per 1000 live births in 1998.4

Social inequalities have been a noted feature of the epidemiology of SIDS for several decades. Non-White ethnicity, single parenthood, teenage pregnancy, and low educational attainment and poverty have been consistently noted as risk factors.5–8 Racial and ethnic disparities in SIDS have been pronounced in the United States, reflecting these socioeconomic inequalities. During the 1980s, Black infants were twice as likely to die as White infants, and Native American infants had a mortality risk 3.5 times greater.9

In this study, we examined social inequalities in risk of SIDS before and after the introduction of the Back to Sleep campaign. If effective new preventive and treatment regimens are taken up inequitably, then they could actually increase any disparities that previously existed in health conditions. Disparities have been observed in receipt of recent advances in primary and secondary prevention. For example, there is evidence that patients with less education and/or lower income are less likely to receive intensive cardiac procedures.10–13 Among persons with diabetes, low socioeconomic status is associated with lack of compliance with regimens to achieve close glucose control,14–16 and among persons with HIV, highly active antiretroviral therapy is less likely to be prescribed to the less educated.17 However, these examples are all complicated and/or expensive treatments. In contrast, a public health preventive intervention that is easily adopted, easily disseminated, and free, such as the Back to Sleep campaign, could reduce inequalities in this largely preventable condition. We proposed 2 alternative hypotheses: (1) that the Back to Sleep campaign would increase social inequalities in SIDS or (2) that social inequalities in SIDS would decrease, and we examined social disparities in risk of SIDS before and after the introduction of the campaign.

MATERIALS

The US Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set

The US National Center for Health Statistics has established a research data set of linked birth and death certificates for all infants born in the United States and those who die in the first year. We used the cohort-format data sets for years 1989 to 1991 and years 1996 to 1998 to represent, respectively, the periods before and after the introduction of the US Public Health Service’s Back to Sleep campaign in June 1994.

Case and Control Groups

We restricted our study to singleton infants without congenital abnormalities or abnormal conditions. The case group (N = 21126) was all infant deaths caused by SIDS, coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.18,19 The control group was all non-SIDS deaths (N = 79 638) and a 10% random sample of infants who survived the first year (N = 2161580). We compared the SIDS case group with each control series to examine the specificity for SIDS of any cohort effects or effects of maternal social class.

Social Class

Mother’s highest level of educational attainment was used as a measure of social class. Mothers were categorized as having either: (1) no education or only elementary education (0–8 years), (2) some high school (9–11 years), (3) graduated high school (12 years), (4) some college education (13–15 years), or (5) graduated from college or beyond (16+ years). College graduation is the reference category for all analyses of education effects.

Statistical Methods

We compared risk of SIDS before and after the Back to Sleep campaign for all mothers and infants and compared rates of SIDS by mother’s education between infants born to non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic women. We used logistic regression to examine the independent and joint effects of education and precampaign and postcampaign cohort status on risk of SIDS. We also examined 3-way interactions between education, cohort status, and race/ethnicity. We then adjusted these models for the following potential confounding variables: region of usual residence of the mother at time of birth; infant sex; mother’s age, nativity (US vs foreign-born), and marital status; mother’s race/ethnicity, parity, gestational age, and birthweight at delivery; 5-minute Apgar score; and mother’s tobacco use during pregnancy. All analyses were weighted to reflect the fact that the comparison group of infants who survived the first year was a 10% sample of this cohort.

Missing Data

Linkage of infant deaths to birth certificates is nearly complete; for example, in 1996, 98% of infant deaths were linked with their corresponding birth records. Some records had missing information on maternal education (4.1%), maternal nativity (0.3%), parity (0.6%), infant gestation (1.3%) and birth-weight (0.2%), 5-minute Apgar score (23.9%), maternal tobacco use during pregnancy (25.8%), information about congenital abnormalities (8.7%), and abnormal conditions (20.8%). None of these records was eliminated from the analyses; rather, we created categorical variables to indicate missing information. There was a statistically significant higher risk of SIDS (P< .05) among infants with missing information about mother’s education (odds ratio [OR] = 1.34), parity (OR = 1.63), gestational age (OR = 1.31), birthweight (OR = 1.67), abnormal conditions (OR = 1.06), and mother’s tobacco use (OR = 1.07).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Descriptive characteristics of mothers and infants for both periods together are shown in Table 1 ▶. The precampaign cohort born in 1989 to 1991 consisted of 13830 infants who died from SIDS, 46829 infants who died of causes other than SIDS, and 1119121 live infants. Mothers of SIDS case subjects in this cohort had a mean education of 11.5 years, compared with 11.8 years for mothers of infants who died of causes other than SIDS and 12.4 years for mothers of live infants. The postcampaign cohort born in 1996 to 1998 consisted of 7296 infants who died from SIDS, 32 809 infants who died of causes other than SIDS, and 1 042 459 live infants. Mothers of infants who died from SIDS in this later cohort had a mean education of 11.7 years, compared with 12.0 years for mothers of infants who died of causes other than SIDS and 12.7 years for mothers of live infants.

TABLE 1—

Maternal and Infant Characteristics of SIDS Case Subjects, Control Subjects Who Died of Non-SIDS Causes, and Live Control Subjects

| SIDS Case Subjects a | Live Control Subjects b | Control Subjects Dead from Non-SIDS Causes c | |

| Education | |||

| Elementary school | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Some high school | 32 | 16 | 23 |

| High school | 35 | 34 | 35 |

| Some college | 14 | 20 | 16 |

| College graduate | 7 | 19 | 11 |

| Age | 23.8 (5.6) | 26.7 (5.9) | 25.7 (6.3) |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 11 | 18 | 19 |

| Midwest | 27 | 22 | 20 |

| South | 36 | 35 | 39 |

| West | 25 | 25 | 22 |

| Nativity | |||

| Born in United States | 92 | 82 | 81 |

| Born outside United States | 8 | 18 | 16 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 58 | 63 | 45 |

| Black | 28 | 15 | 35 |

| Hispanic | 10 | 17 | 16 |

| Other | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Married | 48 | 70 | 50 |

| Parity | |||

| 1 | 30 | 41 | 40 |

| 2 | 34 | 32 | 28 |

| ≥ 3 | 36 | 26 | 30 |

| Tobacco use during pregnancy | 30 | 12 | 14 |

| Female sex | 40 | 49 | 44 |

| Gestation, wk | 38.6 (3.1) | 39.2 (2.3) | 31.6 (7.9) |

| Preterm delivery (> 37 weeks’ gestation) | 18 | 8 | 56 |

| Birthweight, g | 3115 (632) | 3382 (535) | 1893 (1291) |

| Very low birthweight (< 1500 g) | 2 | 0 | 45 |

| Low birthweight (< 2500 g) | 12 | 4 | 12 |

| 5-minute Apgar score | 8.9 (0.7) | 9.0 (0.6) | 5.7 (3.5) |

Note. Values in table are mean and SD for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables

a Total N = 21 126; 1989–1991: N = 13 830; 1996–1998: N = 7296.

b Total N = 2 161 580; 1989–1991: N = 1 050,124; 1996–1998: N = 1 027 144.

c Total N = 79 638; 1989–1991: N = 46 829; 1996–1998: N = 32 809.

The Effect of the Back to Sleep Campaign on SIDS

In unadjusted analyses, infants born in the postcampaign 1996-to-1998 cohort were significantly less likely to die of SIDS (P< .001) than infants born from 1989 to 1991 (OR = 0.57; 95% CI = 0.55, 0.58. For white mothers, the OR was 0.58 (95% CI = 0.56, 0.60). This decline was more pronounced (P< .05) for infants born to Hispanic women (OR = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.47, 0.56) and less pronounced (P< .01) for infants born to Black women (OR = 0.63; 95% CI = 0.60, 0.66). Thus, the race disparity increased after the Back to Sleep campaign.

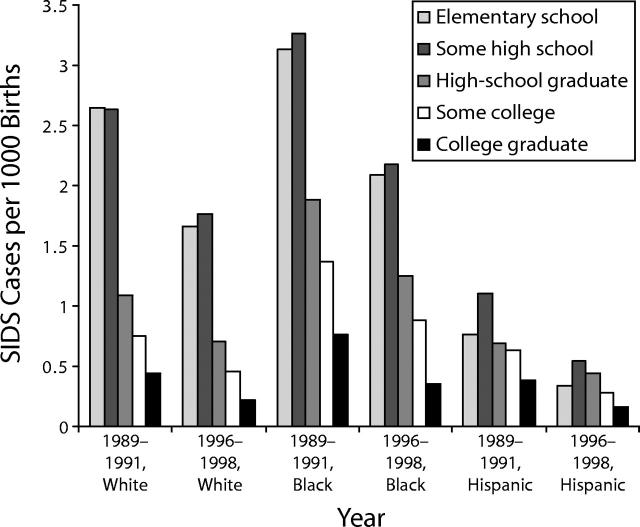

Figure 1 ▶ shows rates of SIDS per 1000 live births by mother’s race/ethnicity and highest educational achievement in the 1989-to-1991 and the 1996-to-1998 birth cohorts. Rates declined within each education and race/ethnicity category. Across all educational groups, and in both periods, infants born to Black mothers were at higher risk of death than those born to White mothers, and infants born to Hispanic mothers were at lower risk of death than those born to White mothers.

FIGURE 1—

Rates of SIDS per 1000 live births by mother’s race/ethnicity and social class in the before and after Back to Sleep birth cohorts.

Precampaign and Postcampaign Social Class Disparities

Table 2 ▶ shows the odds ratios for the effects of different categories of maternal education on SIDS risk in the precampaign and postcampaign cohorts. Risk of SIDS is estimated in relation to 2 comparison groups: infants who survived the first year and infants who died of causes other than SIDS. Odds ratios are estimated in both unadjusted models (model 1) and models adjusted for maternal and infant characteristics (model 2). Because preliminary analyses did not identify significant 3-way interactions between maternal education, cohort, and race/ethnicity, which would have suggested that cohort changes in the effect of maternal education on SIDS risk varied by race/ethnicity, we report results for all race/ethnic groups combined.

TABLE 2—

Effect of Mother’s Education on Risk of SIDS in the Precampaign and Postcampaign Birth Cohorts

| Risk of SIDS Death vs. Infant Surviving First Year | Risk of SIDS Death vs. Infant Death from Other Cause | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||||

| 1989–1991 | 1996–1998 | P | 1989–1991 | 1996–1998 | P | |

| Model 1 (unadjusted) | ||||||

| College graduate or beyond (reference category) | 1.00 (. . . ) | 1.00 (. . . ) | . . . | 1.00 (. . . ) | 1.00 (. . . ) | . . . |

| Some college | 1.77 (1.64, 1.92) | 2.16 (1.95, 2.40) | .003 | 1.31 (1.20, 1.43) | 1.45 (1.30, 1.62) | .161 |

| Completed high school | 2.56 (2.38, 2.75) | 3.29 (3.00, 3.61) | < .001 | 1.44 (1.33, 1.56) | 1.66 (1.51, 1.84) | .029 |

| Some high school | 5.15 (4.79, 5.53) | 6.30 (5.74, 6.91) | < .001 | 2.03 (1.87, 2.20) | 2.43 (2.20, 2.69) | .006 |

| No education/elementary school only | 2.99 (2.73, 3.27) | 3.16 (2.79, 3.58) | .474 | 1.35 (1.22, 1.49) | 1.48 (1.30, 1.70) | .259 |

| Model 2 (adjusted) | ||||||

| College graduate or beyond (reference category) | 1.00 (. . . ) | 1.00 (. . . ) | . . . | 1.00 (. . . ) | 1.00 (. . . ) | . . . |

| Some college | 1.08 (0.99, 1.17) | 1.27 (1.14, 1.41) | .015 | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | 1.15 (1.02, 1.33) | .282 |

| Completed high school | 1.14 (1.06, 1.23) | 1.43 (1.30, 1.57) | < .001 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) | 1.13 (1.01, 1.26) | .098 |

| Some high school | 1.45 (1.34, 1.58) | 1.86 (1.68, 2.05) | < .001 | 1.07 (0.97, 1.18) | 1.19 (1.06, 1.34) | .139 |

| No education/elementary school only | 1.52 (1.37, 1.68) | 1.74 (1.53, 1.99) | .078 | 0.98 (0.87, 1.11) | 0.99 (0.85, 1.16) | .914 |

Note. OR = odds ratios; CI = confidence ratio. P is the significance level of the test of differences in the ORs. ORs for model 2 were adjusted for: region of residence; infant sex; mother’s age, nativity, marital status, race/ethnicity, tobacco use during pregnancy, and parity; gestational age; birthweight; and 5-minute Apgar score.

Three trends are notable in this table. First, the risk of SIDS among women with no education or only elementary education does not fit expectations of increased risk among women of lower social class. Because education to age 16 is compulsory in the United States, women with no or only elementary education are a small and heterogeneous group that includes foreign-born women as well as some women with severe health or cognition problems; it is not surprising that relationships between education and health are anomalous in this category. It is also possible that this finding is explained in part by the well-known paradox that some ethnic minority groups in the United States have much better reproductive health than expected given their socioeconomic status.20

Second, with the exception of the anomalous group of women with only elementary or no education, within each period, lower levels of maternal education were associated with higher risk of SIDS versus an infant surviving the first year. This is also true for the risk of SIDS versus non-SIDS death in the unadjusted model. However, after adjusting for maternal and infant risk characteristics, such as low birthweight and parity, there is little evidence of a social gradient in risk of SIDS compared with any other cause of death in the 1989-to-1991 cohort. In the 1996-to-1998 cohort, there is evidence of an education effect on risk of SIDS versus non-SIDS deaths: infants whose mothers have less than a college education are at greater risk of dying from SIDS than from any other cause.

Third, education differentials for risk of SIDS increase rather than decline in the later period. In fact, for all educational categories in both unadjusted and adjusted models, odds ratios for educational attainment relative to college graduates are higher in 1996 to 1998 than in 1989 to 1991. The increases in odds ratios are statistically significant in all of the comparisons to surviving infants (except for the anomalous lowest category of education). For example, compared with college graduates, high school graduates’ risk of having an infant die of SIDS was 14% higher in 1989 to 1991 and 43% higher in 1996 to 1998. The increase in risk was statistically significant (P< .001).

DISCUSSION

In this case-cohort study, we found that social class inequalities in SIDS (measured by maternal education) did not narrow after the Back to Sleep campaign compared with the precampaign era. Although absolute risk of SIDS was reduced for all social class groups, a widening social class inequality was evident; women with more education have experienced a greater decline than women with less education.

The strengths of our study include the fact that it is population-based, including all SIDS deaths in the US for the 2 study periods, and a random sample of non-SIDS deaths and live infants, allowing direct estimation of population rates of SIDS over time and in each social class group. Our study is also large enough to allow precise estimation of interaction effects between social class and birth cohort. The high degree of linkage in the US Linked Birth-Death Data Sets is also a strength.

Nevertheless, our study has some limitations. First, around 4% of records had missing information on mother’s education and these infants had an increased risk of SIDS. It seems likely that mothers with low social class will be missing education information more often than mothers with high social class; therefore, our estimates of the effects of lesser educational attainment, as well as our estimates of social class inequalities, are conservative. Second, although we were able to adjust for a wide range of potential confounders, we were lacking information on some strong risk factors for SIDS, such as breast-feeding, and had incomplete information on others, such as mother’s tobacco use during pregnancy. Although our intention was to describe changes in social inequality in SIDS risk, information on breast-feeding and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, among other factors, would be useful in explaining the continuing and widening social class inequalities that we present. It is also possible that changes in society other than the Back to Sleep campaign, such as welfare reform and economic changes, might have had an impact. However, we report widening social inequalities in SIDS deaths but not in infant deaths from other causes, which strengthens our interpretation that the campaign, rather than any broader social processes, has led to the increased gap. Third, we used mother’s education as a proxy for social class, which may not accurately reflect the socioeconomic context of the households in which women live.21–24 However, in a Belgian study, low maternal education, but not paternal occupational status, was associated with parents reporting a higher number of SIDS-related risk behaviors.25

Before the epidemiological studies establishing an association between infant sleep position and SIDS were published in the early 1990s (for example,26–28), little was known about risk factors for SIDS that could help parents or clinicians effectively reduce risk.29 The long-standing social gradient in SIDS risk was probably due, in part, to increased exposure to breast-feeding and decreased exposure to tobacco smoke among infants in higher social class groups. Home monitoring systems, used to detect periods of apnea and bradycardia in infants believed to be at high risk of SIDS, were more frequently used for White infants than for those in minority racial/ethnic groups30 (perhaps because of disparities in ability to pay or discriminatory attitudes about parents’ ability to comply with monitoring), but were, in any case, ineffective at preventing SIDS.31 The epidemiological evidence that reducing the population prevalence of prone infant sleep position could dramatically lower SIDS rates offered a seemingly ideal intervention for a public health campaign: simple and free. In theory, public health interventions with these qualities ought to lead to a reduction in health inequalities in that there would seem to be few barriers to universal uptake of the intervention. Mothers can be advised at delivery about infant sleep position, whether or not they receive antenatal care or postnatal medical care for their infant. Clinicians can provide written and verbal information about infant sleep position in a myriad of different clinical settings. Mass media outlets can be used to publicize the public health message. Despite these features of the Back to Sleep campaign, however, social class inequalities in SIDS have grown since its introduction.

There are 2 possible, and not mutually exclusive, explanations for this phenomenon: (1) either the information about infant sleep position is not being disseminated as fully to women in low social class groups or (2) women in low social class groups are receiving appropriate advice but not heeding it.

There is some evidence that information about the protective effects of supine infant sleep position is not equally disseminated to all social class groups. In a study based in Louisville, Ky, researchers compared the advice given to mothers who received pediatric care for their children in a private practice clinic serving mostly White middle- and upper-income families and that given to families who received care at a clinic serving mostly inner-city, low-income African Americans.32 Whereas 72% of the private practice families reported receiving advice about sleep positions, only 48% of the families served by the inner-city clinic reported receiving such advice. In the National Infant Sleep Position Study, conducted between 1994 and 1998, 21% of night-time caregivers of infants reported not receiving advice from any source to place their infants in a supine position to sleep.33 In the 1997 to 1998 period, 3 to 4 years after the initiation of the Back to Sleep campaign, 40.7% of care-givers still reported receiving no advice on sleep position from a physician. In the Chicago Infant Mortality Study, prone sleep position was recommended to a higher proportion of Black mothers than mothers of other race/ethnicity.34

Despite receiving recommendations about infant sleep position, some parents and nighttime caregivers continue to place infants in a prone or side-lying position, rather than supine. In the Louisville study cited above, nearly three quarters of families attending the private clinic followed the advice they were given on infant sleep position, whereas only 54% of the inner-city families reported following the advice they were given.32 In the National Infant Sleep Position Study, most caregivers (86%) who reported placing their infants in a prone sleep position had actually received advice from some source to place the infant supine.33 Caregivers most likely to place their infants prone were mothers of low social class and mothers with more than 1 child. Black mothers, younger mothers, mothers with more than 1 child, and those who lived in a southern or mid-Atlantic state were most likely to place their infants prone. Similar findings were reported in a Belgian study.25 Little empirical evidence is available to help illuminate the cultural barriers to acceptance of supine sleep position among families of low social class, although there is much speculation about the role of the advice of family and friends. We were unable to identify any qualitative studies of choices around infant sleeping environment in low social class or ethnic minority groups in the United States, although such studies have been conducted in middle class and ethnic minority groups in Australia and New Zealand.35,36 More research is needed to understand how night-time caregivers in high-risk groups come to make decisions about infant sleep position, particularly when they have been advised to the contrary.

It is also possible that the widened social class gap in SIDS after the introduction of the Back to Sleep campaign reflects social inequalities in known and unknown risk factors for SIDS that were previously somewhat masked by the widespread prevalence of prone sleep. In the United Kingdom, Macfarlane et al.37 have drawn attention to the fact that interactions between socioeconomic status and risk factors for SIDS have not been fully explored. Enhanced efforts to promote supine sleep, as well as breast-feeding, the avoidance of soft bedding, and exposure to tobacco, among families of low social class are clearly a necessity.

The US public health goals for the nation, Healthy People 2010, place special emphasis on the reduction of health inequalities.38 Our study illustrates persistence and even growth in inequalities, suggesting the importance of institutional and cultural barriers, despite the availability of a free, easy, and effective behavioral intervention.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors K. Pickett and D. Lauderdale originated the research question. Y. Luo conducted the data analysis. All of the authors contributed to the interpretation of results and writing of the article.

Human Participant Protection This study was reviewed by the University of Chicago institutional review board and deemed exempt.

References

- 1.Anderson RN, Smith BL. Deaths: leading causes for 2001. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003;52:1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics AAP Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS. Positioning and SIDS [published erratum appears in Pediatrics. 1992;90:264]. Pediatrics. 1992;89:1120–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willinger M, Hoffman HJ, Hartford RB. Infant sleep position and risk for sudden infant death syndrome: report of meeting held January 13 and 14, 1994, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. Pediatrics. 1994;93:814–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 1998. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2000. [PubMed]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sudden infant death syndrome—United States, 1980–1988. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41:515–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sudden infant death syndrome—United States, 1983–1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:859–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman HJ, Damus K, Hillman L, Krongrad E. Risk factors for SIDS. Results of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development SIDS Cooperative Epidemiological Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;533:13–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman HJ, Hillman LS. Epidemiology of the sudden infant death syndrome: maternal, neonatal, and postneonatal risk factors. Clin Perinatol. 1992;19:717–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudden infant death syndrome as a cause of premature mortality—United States, 1984 and 1985. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:644–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hetemaa T, Keskimaki I, Salomaa V, Mahonen M, Manderbacka K, Koskinen S. Socioeconomic inequities in invasive cardiac procedures after first myocardial infarction in Finland in 1995. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philbin EF, McCullough PA, DiSalvo TG, Dec GW, Jenkins PL, Weaver WD. Socioeconomic status is an important determinant of the use of invasive procedures after acute myocardial infarction in New York State. Circulation. 2000;102(19 Suppl 3):III107—III115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen JJ, Wan TT, Perlin JB. An exploration of the complex relationship of socioecologic factors in the treatment and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in disadvantaged populations. Health Serv Res. 2001; 36:711–732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alter DA, Naylor CD, Austin P, Tu JV. Effects of socioeconomic status on access to intensive cardiac procedures and on mortality after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1359–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd CE, Wing RR, Orchard TJ, Becker DJ. Psychosocial correlates of glycemic control: the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications (EDC) Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1993;21:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaturvedi N, Stephenson JM, Fuller JH. The relationship between socioeconomic status and diabetes control and complications in the EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auslander WF, Thompson S, Dreitzer D, White NH, Santiago JV. Disparity in glycemic control and adherence between African-American and Caucasian youths with diabetes. Family and community contexts. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1569–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassetti S, Battegay M, Furrer H, et al. Why is highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) not prescribed or discontinued? Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willinger M, James LS, Catz C. Defining the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): deliberations of an expert panel convened by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatr Pathol. 1991;11:677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1980. DHHS publication PHS 80–1260.

- 20.Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberatos P, Link BG, Kelsey JL. The measurement of social class in epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:87–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee PR, Moss N, Krieger N. Measuring social inequalities in health. Report on the Conference of the National Institutes of Health. Public Health Rep. 1995; 110:302–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krieger N, Fee E. Man-made medicine and women’s health: the biopolitics of sex/gender and race/ethnicity. Int J Health Serv. 1994;24:265–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger N. Women and social class: a methodological study comparing individual, household, and census measures as predictors of black/white differences in reproductive history. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahn A, Bauche P, Groswasser J, Dramaix M, Scaillet S. Maternal education and risk factors for sudden death in infants. Working Group of the Groupe Belge de Pediatres Francophones. Eur J Pediatrics. 2001;160:505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dwyer T, Ponsonby AL, Newman NM, Gibbons LE. Prospective cohort study of prone sleeping position and sudden infant death syndrome. Lancet. 1991;337:1244–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engelberts AC, de Jonge GA, Kostense PJ. An analysis of trends in the incidence of sudden infant death in The Netherlands 1969–89. J Paediatr Child Health. 1991;27:329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell EA, Brunt JM, Everard C. Reduction in mortality from sudden infant death syndrome in New Zealand: 1986–92. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70:291–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunteroth WG. Crib Death: The Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Armonk, NY: Futura; 1995.

- 30.Malloy MH, Hoffman HJ. Home apnea monitoring and sudden infant death syndrome. Prevent Med. 1996; 25:645–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apnea, sudden infant death syndrome, and home monitoring. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):914–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray BJ, Metcalf SC, Franco SM, Mitchell CK. Infant sleep position instruction and parental practice: comparison of a private pediatric office and an inner-city clinic. Pediatrics. 1997;99:E12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willinger M, Ko CW, Hoffman HJ, Kessler RC, Corwin MJ. Factors associated with caregivers’ choice of infant sleep position, 1994–1998: the National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA. 2000;283:2135–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hauck FR, Moore CM, Herman SM, et al. The contribution of prone sleeping position to the racial disparity in sudden infant death syndrome: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110:772–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowe J. A room of their own: the social landscape of infant sleep. Nurs Inq. 2003;10:184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tipene-Leach D, Abel S, Finau SA, Park J, Lenna M. Maori infant care practices: implications for health messages, infant care services and SIDS prevention in Maori communities. Pac Health Dialog. 2000;7:29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macfarlane A. Sudden infant death syndrome. More attention should have been paid to socioeconomic factors. BMJ. 1996;313:1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/