Abstract

Objective. We sought to examine the accessibility of health clubs to persons with mobility disabilities and visual impairments.

Methods. We assessed 35 health clubs and fitness facilities as part of a national field trial of a new instrument, Accessibility Instruments Measuring Fitness and Recreation Environments (AIMFREE), designed to assess accessibility of fitness facilities in the following domains: (1) built environment, (2) equipment, (3) swimming pools, (4) information, (5) facility policies, and (6) professional behavior.

Results. All facilities had a low to moderate level of accessibility. Some of the deficiencies concerned specific Americans with Disabilities Act guidelines pertaining to the built environment, whereas other deficiency areas were related to aspects of the facilities’ equipment, information, policies, and professional staff.

Conclusions. Persons with mobility disabilities and visual impairments have difficulty accessing various areas of fitness facilities and health clubs. AIMFREE is an important tool for increasing awareness of these accessibility barriers for people with disabilities.

An estimated 54 million Americans have disabilities, or approximately one out of every five individuals.1 Incidence of disability is likely to be higher in older populations.2 Relative to the general population, people with disabilities are more likely to be sedentary,3–7 have greater health problems,8–11 and have more physical activity barriers.12–16 The Healthy People 2010 report7 notes that significantly more people with disabilities reported having no leisure-time physical activity (56% among persons with disabilities vs 36% among nondisabled individuals). These patterns of low physical activity raise serious concerns regarding the health status of people with disabilities, particularly as they enter their later years, when the effects of the natural aging process are compounded by years of sedentary living, thereby resulting in further decline in health and physical fitness.17

The chapter of Healthy People 2010 entitled Disability and Secondary Conditions18 suggests that the significantly lower rate of participation among people with disabilities may be related to environmental barriers, including architectural barriers, organizational policies and practices, discrimination, and social attitudes, and recommends that public health agencies begin to evaluate which environmental factors enhance or impede participation. Although members of the general population obtain most of their physical activity in outdoor settings such as neighborhood streets, shopping malls, parks, and walking/ jogging paths,19–23 access to walking for people with mobility disabilities who have difficulty walking (because of, e.g., arthritis, extreme obesity, or balance impairments), cannot walk (because of, e.g., some form of paralysis), or have limited or no vision is often restricted by these inaccessible environments. Some streets do not have safe curb cuts; sidewalks are damaged and thus create a higher risk of falling; walkways or walking paths are too narrow for a wheelchair user and partner to walk side-by-side; many communities do not have sidewalks; or the terrain has too steep a grade or slope. Other problems with outdoor environments include unsafe neighborhoods, poor weather causing slippery or impassable sidewalks, insufficient number of benches along a trail for people who need frequent rest periods, poorly designated signage, no accessible bathrooms along a trail or path, and no handicapped parking spaces in close proximity to a trail.14

Given the high level of inaccessibility of outdoor physical activity environments pertaining to individuals with mobility disabilities and visual impairments, health clubs may present a viable alternative for participating in physical activity. To date, there has been little empirical research on the accessibility of fitness facilities/health clubs for people with disabilities. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the accessibility of a national sample of fitness facilities/health clubs.

METHODS

We developed an instrument that measures environmental accessibility of fitness and recreation settings for people with mobility disabilities and visual impairments. We refer to this instrument as Accessibility Instruments Measuring Fitness and Recreation Environments (AIMFREE).24 AIMFREE consists of 6 sub-scales related to accessibility of (1) built environment, (2) equipment, (3) information, (4) policies, (5) swimming pools, and (6) professional behavior (attitudes and knowledge). The instrument was developed from the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) guidelines for the built environment, and the remaining sections were developed from extensive national focus group research involving persons with disabilities, fitness and recreation professionals, architects, engineers, and city and park district managers.14 Sample items from the instrument appear in Table 1 ▶. The AIMFREE instrument has been found to have good test-retest and interrater reliability.24 A detailed discussion of the instrument’s development, reliability, and validity of the instrument has been published in a previous paper.24

TABLE 1—

Description of the AIMFREE Subscales

| Subscales | Sample Items |

| Built environment | Bathroom: Is there an unobstructed turning radius of at least 60 in in front of restroom doors? Is the sink counter 34 in or less above the floor?Elevator: Is there a visual signal on each floor indicating which elevator is approaching? |

| Information | Do room identification signs have raised characters or symbols? Do televisions and multimedia employ opened/closed captioning? |

| Equipment | Does the facility provide exercise equipment that does not require transfer from wheelchair to machine? Are buttons on the equipment raised from the panel surface? |

| Policies | Is the accessibility of the facility periodically reviewed? Can a consumer’s personal assistant be allowed to enter the facility without incurring additional charges? |

| Professional behavior | Do staff members make eye contact when speaking to consumers? Do staff members ask consumers whether they need assistance before attempting to help them? |

| Swimming pool | Are pool lift controls accessible from the deck level? Does the pool have a ledge to hold onto when entering the water? |

Evaluators

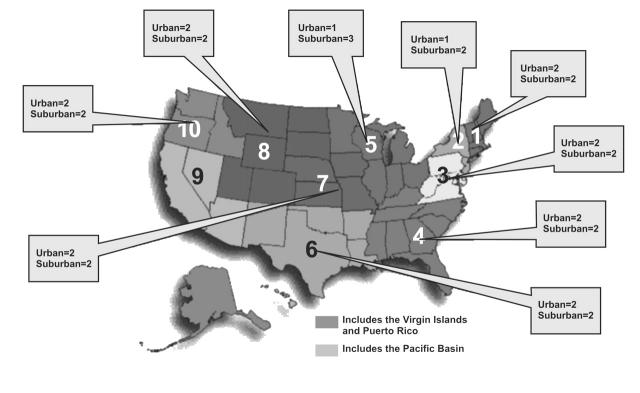

Thirty-five fitness and recreation professionals (10 males, 25 females) were recruited for this study through contacts with the ADA Disability, Business, and Technical Assistance Centers (DBTACs) located in 9 of 10 regions across the United States, as illustrated in Figure 1 ▶. The 10 regions represent catchment areas of the DBTACs of the ADA. These regions included the following: New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont), Northeast (New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands), Mid-Atlantic (Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia), Southeast (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee), Great Lakes (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin), Great Plains (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska), Rocky Mountains (Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming), Southwest (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas), and Northwest (Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington). At least one rater in each region, called the “gold-trained rater,” was selected and trained by the present investigators in the use of the AIMFREE instrument. Gold-trained raters (two men, eight women) participated in a two-day training session in Chicago to learn how to use the instrument. Persons serving as gold-trained raters were professionals in the areas of fitness, recreation, or rehabilitation and had experience related to working with persons with disabilities. Additional fitness and recreation staff were then recruited and trained by each gold-trained rater within each geographic region to perform assessments of participating facilities.

FIGURE 1—

Distribution of facilities serving as test sites by DBTAC region and the number of facilities within each region by community type (urban vs rural).

Facilities

A convenience sample of 35 facilities (19 in urban areas, 16 in suburban areas) was selected from 9 of the 10 geographic regions. An additional 24 facilities were contacted but declined to participate in the study. A trained rater within each of the nine regions was asked to recruit four facilities to serve as test sites. In order to obtain permission from four facilities, trained raters were instructed to identify 8 to 10 facilities in their region. All fitness facilities in the study contained a swimming pool and an exercise equipment area and had at least one staff member who agreed to participate in the study. Because of the time and cost involved in traveling to these areas, facilities in rural regions were not sampled. The 35 assessed facilities included 16 for-profit facilities (privately owned and operated) and 19 nonprofit facilities, which included 5 community centers, 4 recreation centers, 3 wellness centers, 2 rehabilitation-based facilities, 2 aquatic centers, 2 college-based facilities, and 1 hospital-based center.

Procedures

A trained professional evaluator (gold-trained rater), and one to two staff members recruited by the gold-trained rater, evaluated the facilities. Each gold-trained rater assessed all facilities within his or her region. Additionally, a facility staff member assessed each facility a second time. Each facility was assessed twice: once by the trained rater and once by a staff member. Ratings from each rater were averaged to create a single composite score. On most of the AIMFREE subscales, raters were required to answer items on the basis of direct observation of the facility. The Policies subscale required that the rater obtain information from staff located at the facility.

Data Analysis

Each of the subscales comprising the AIMFREE instrument was submitted to Rasch analysis.24 The Rasch measurement model is a modern psychometric analytic technique developed explicitly to interpret multichoice surveys. We chose the Rasch model for three reasons. First, Rasch scores are easily computed. Second, Rasch scores are based on observed criteria and are therefore empirically derived and not imposed. Third, a facility’s level of accessibility can be directly compared with the scale’s items and their estimated level of difficulty. This ability to make direct comparisons between facilities and items allows users to identify “next steps” (i.e., failed items just above the facility’s level of accessibility) for incrementally improving a facility’s accessibility.

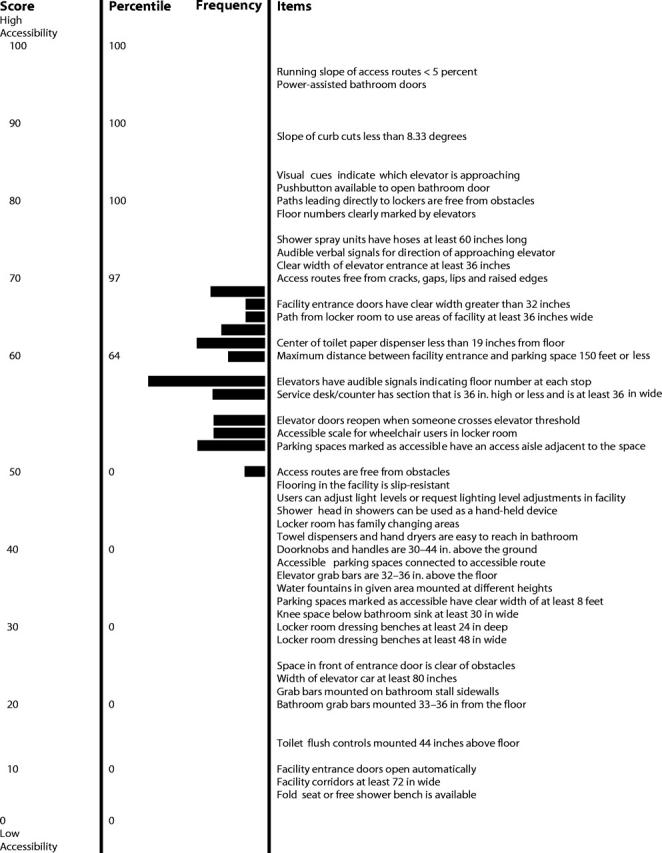

Under Rasch model expectations, a facility with higher accessibility always has a higher probability of having an accessibility feature than a facility with lower accessibility. Likewise, a more “difficult” item (i.e., accessibility feature) always has a lower probability of being present in a facility than a less difficult item, regardless of the accessibility level of the facility. As an illustration of the relationship between item difficulty and facility accessibility from the Rasch perspective, many facilities have corridors that are 72 inches wide or wider and therefore this accessibility feature is relatively easy to endorse (Figure 2 ▶). By contrast, relatively few facilities have power-assisted bathroom doors; therefore, this item is relatively difficult to endorse (Figure 2 ▶). A facility with a high level of accessibility would be more likely to possess both of these accessibility features compared with a facility with low accessibility. The placement of items according to their level of difficulty and the placement of facilities according to their level of accessibility is graphically illustrated by the variable map in Figure 2 ▶. Rather than estimating the accessibility level on the basis of the percentage of endorsed or passed items, both item difficulty calibrations and facility accessibility levels are placed on an equal-interval logit (log odds ratio) scale. This provides a greater precision of measurement and more accurate comparisons of facilities and items. Furthermore, the placement of facility accessibility and item difficulty on a common scale allows direct comparison of facilities and items.

FIGURE 2—

Item and facility map for the AIMFREE built environment subscale. Frequency refers to the number of facilities (horizontal bars, no scale); the corresponding accessibility level score is shown in the left-hand column.

Rasch scores from each subscale were linearly transformed into a scale of 0 to 100, with a mean score of 50, using procedures outlined by Schumacker.25 A score > 50 indicates above-average levels of accessibility, whereas a score < 50 indicates below-average levels of accessibility. In addition, percentile rankings corresponding to scale scores are also presented. By employing the Rasch model and using variable maps, we can observe the relationship between facility accessibility and the probability of the facility possessing various accessibility features.

RESULTS

Accessibility was assessed in 6 areas: Built Environment, Equipment, Swimming Pool, Information, Policies, and Professional Behavior. Figure 2 ▶ presents the item and facility map for the AIMFREE Built Environment composite scale, and Table 2 ▶ presents abbreviated item maps with selected items for the remaining subscales: Equipment, Swimming Pool, Information, Policies, and Professional Behavior.

TABLE 2—

Selected Items With Associated Accessibility Percentile Ranks for 5 AIMFREE Subscales.

| Accessibility Percentile | Equipment | Swimming Pool | Information | Policies | Professional Behavior |

| 96–100 | Wheelchair ergometer | Transfer wall | Audible cues indicate location in facility | Disability determines member fees | |

| 91–95 | Seats on equipment ≥ 18 in wide | Information in pictogram format | Information in Braille provided on request | Talk directly to personal assistant | |

| 86–90 | Arm/leg ergometer | Pool ramp slope < 8.33 degrees | Images of persons with disabilities in facility brochures | Membership fee prorated based on percentage of facility that is accessible | |

| 81–85 | Zero-depth entry | Information in large print format | |||

| 76–80 | Clear space by equipment 36 × 48 in | Wet/dry ramp | Information in large print provided on request | ||

| 71–75 | Pool ramp landings level | ||||

| 66–70 | Equipment used from a wheelchair | Therapeutic pool | Marquees, bulletin boards in alternative format | Person(s) with disabilities serve on advisory board | |

| 61–66 | Warning texture around pool perimeter | ||||

| 56–60 | Bowflex Versatrainer | Pool lift descends 18–20 in below water | Provide list of assistive device manufacturers upon request | ||

| 51–55 | |||||

| 46–50 | Armcrank ergometer | Pool lift | Brochures indicate persons with disabilities welcome to the facility | Advertise accessible services | |

| 41–45 | |||||

| 36–40 | Alternative format on cardio equipment | ||||

| 31–35 | Television with open/closed captioning | Train new staff on how to assist persons with disabilities in making transfers from their wheelchair | Staff provided good ideas on improving fitness | ||

| 26–30 | Accessible resistance machines | Tread width of steps into pool ≥ 7 in | Raised letters/symbols on room signs | Lifeguards available in pool area | |

| 21–25 | Steps extend 18–20 in. below water | Sign text in all capital letters | |||

| 16–20 | Lowest weight setting suitable for low strength | Lifeguards available | Door signs on latch side of door | Formal process for handling accessibility complaints | |

| 11–15 | Pool depth markers clearly visible | Designated employee to oversee ADA compliance | Staff asked if help was needed before providing assistance. | ||

| 6–10 | 60 × 60 in clear space by each pool entry point | Signs: light text on dark background | Personal assistants can enter facility without charge | Staff members uncomfortable with persons with disabilities | |

| 0–5 | Cardio equipment buttons easily readable; Low mph treadmill | Pool lanes ≥ 36 in wide | Signs have glare-free surface | Service animals allowed in facility | Staff made eye contact when speaking to consumers. |

The composite scale illustrated in Figure 2 ▶ includes items from several AIMFREE sub-scales, including Parking Areas, Bathrooms, Locker Room, Elevator, Access Routes, and Water Fountains. Facilities fell within a rather narrow range of accessibility level, with most facilities achieving scores between 50 and 70. The mean level of accessibility for facilities sampled was 58.5, slightly higher than the average level of difficulty for the instrument, which was set at 50. The majority of facilities in the study were likely ( > 50% probability) to have (1) slip-resistant flooring, (2) adjustable lighting levels, (3) hand-held shower heads in facility showers, (4) family changing rooms, (5) accessible routes connecting the facility to accessible parking spaces, (6) locker room dressing benches of suitable size, (7) grab bars in elevators and bathroom stalls, (8) fold seats or shower benches in shower areas, and (9) automatic entrance doors. Facilities were also likely to have accessibility features consistent with ADA Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) pertaining to elevators, bathrooms, entrance doors, water fountains, and parking areas, such as elevator cars being 80 inches wide and toilet flush controls being mounted 44 inches above the floor (bottom of Figure 2 ▶). In contrast, most facilities were unlikely (< 50% probability) to have access routes and curb cuts with a running slope below the ADA recommended limits (5% grade for access routes and 8.33% grade for curb cuts). Facilities were also unlikely to provide power-assisted or pushbutton-operated doors; visual and audible signals in elevators; access routes free from cracks, gaps, and raised edges; hand-held showerhead units; and obstacle-free paths to lockers.

A number of structural improvements would be necessary for improving a facility’s accessibility from the mean score of 58.5 to a score of 75. Structural changes would have to be made to elevators so that verbal cues regarding current floor and elevator direction are given to assist visually impaired individuals. Facility and elevator entrances would require greater clear width to facilitate wheelchair access. Access routes would require resurfacing to eliminate cracks, gaps, lips, and raised edges, which can pose a hazard to someone with limited balance and/or who uses a cane for mobility. Other changes include ensuring that floor numbers are clearly visible by elevators and that paths to lockers are free from obstacles.

Table 2 ▶ presents abbreviated item maps for the Equipment, Swimming Pool, Information, Policies, and Professional Behavior scales, which are described in separate sections below.

Equipment

Examination of the arrangement of items according to their estimated level of difficulty for the AIMFREE Equipment subscale indicates that exercise equipment specifically adapted or designed for persons with disabilities was less prevalent in facilities sampled compared with general purpose equipment. For example, although most facilities were highly likely (95%) to provide low-speed treadmills, only facilities at the 90th percentile or above were likely to provide a wheelchair or arm ergometer. Having adequate space for transfer from wheelchair to exercise machine was also an issue for most facilities; <25% of facilities provided adequate clear space adjacent to exercise equipment. Conversely, most of the facilities sampled were found to meet accessibility criteria, reflected in items related to basic access of the equipment area as well as basic features of exercise equipment, including easily readable displays and buttons on cardio equipment, and weight settings on strength machines light enough for individuals with low strength. Other frequently endorsed items (not listed in Table 2 ▶) included the ability to adjust seat height on exercise machines, the ability to change weight settings on machines without having to get off of the machine, pushbuttons that open doors leading to the equipment area, doors with sufficient clear width to facilitate wheelchair access, and paths in exercise equipment areas being made of a nonslip surface.

Swimming Pools

Similar to the Equipment subscale, the ordering of items on the basis of estimated difficulty level for the Swimming Pool subscale progresses from more general (more frequently endorsed) accessibility features to more disability-specific (less frequently endorsed) items. Although nearly all facilities sampled had clearly visible pool depth markers and adequate clear space adjacent to pool entry points, specific accessibility features, such as transfer walls and zero-depth entry, were considerably less common. This finding, however, may reflect a preference for other types of devices that facilitate pool entry, such as wet/dry ramps and pool lifts, which were found in approximately 25 and 50% of facilities surveyed, respectively.

Information

The AIMFREE Information subscale covers a broad range of information-related access issues, from aspects of facility signage to the provision of alternative formats and inclusion of persons with disabilities in facility brochure text and images. Approximately 70% of the facilities sampled complied with ADAAG guidelines concerning signage, including criteria regarding text size and font, text color and capitalization, and sign placement and inclusion of alternate formats (raised letters, pictograms) on room-identification signs. Facilities were less responsive to accessibility problems related to other sources of information, including brochures, marquees, bulletin boards, and television/multimedia. Less than one third of the facilities were likely to provide information on marquees and bulletin boards in one or more alternative formats. Only facilities at or above the 85th percentile were likely to include images of persons with disabilities in facility brochures. In addition, < 10% of facilities (i.e., facilities above the 90th percentile) were likely to provide audible cues as a means of indicating one’s present location in the facility.

Policies

As shown in Table 2 ▶, nearly all of the facilities allowed service animals in the facility and also allowed personal assistants to enter the facility without incurring additional charges. More than one half of the facilities reported providing training to new staff members on how to assist individuals in transferring from wheelchairs to exercise equipment or swimming pools. Having a formal procedure to handle accessibility-related complaints and a staff person overseeing ADA compliance were also common. However, facilities were less likely to include persons with disabilities on advisory boards. Approximately one half of the facilities advertised their accessible services. The more difficult items on the Policies subscale, accessibility criteria met by < 25% of the facilities, concerned the availability of information in various alternative formats (e.g., large print or Braille) and the adjustment or prorating of membership fees for persons with disabilities. The arrangement of items in the Policies sub-scale suggests that the policies more difficult to implement reflected underlying economic issues. For example, advertising accessible services and providing facility information in alternative formats was not done because of the extra cost.

Professional Behavior

Unlike the other AIMFREE subscales in which items generally covered the entire range of accessibility scores, all but one of the items on the Professional Behavior sub-scale were quite easy to pass (Table 2 ▶). Consequently, accessibility scores on this subscale were generally in the above-average range of the instrument. It should be noted, however, that professionals completing the instrument observed facility staff over a relatively short period of time, which would make the observation of low base-rate behaviors more difficult to assess, and staff members were aware that they were being evaluated, which may have caused them to modify their behavior in an effort to be seen in a positive light. Facility staff members were found to demonstrate positive behaviors when interacting with persons with disabilities. More than 65% of facilities in the study had staff members who were perceived as providing good ideas to persons with disabilities on how to improve fitness. Staff members in > 85% of the facilities were likely to ask consumers with disabilities if they needed help before providing assistance. Staff members in virtually all of the facilities were found to make eye contact while speaking to consumers with disabilities.

Additional examination of responses on the Professional Behavior subscale revealed a combination of positive and negative responses. Despite the relatively high scores on this subscale, some negative responses were recorded. Although a personal assistant did not accompany most persons with disabilities who participated in the study, in cases in which a personal assistant was present, facility staff members were found in several instances to talk directly to the personal assistant rather than to the disabled person. Professionals observing facility staff generally answered “yes” to the question “Did staff members appear uncomfortable or impatient when helping consumers?”

DISCUSSION

The results of this descriptive-exploratory study identified various areas of fitness facilities and health clubs that may be difficult to access by persons with mobility disabilities and visual impairments. Although the facilities in the present study may not represent the entire cross section of facilities in the United States with respect to accessibility level, the present findings are consistent with earlier research that reported a moderate to high degree of inaccessibility of various fitness facilities located in Kansas and Western Oregon.12,26

Some of the deficiencies evidenced in the facilities sampled concerned specific ADAAG guidelines pertaining to the built environment, whereas other barriers were related to aspects of the facilities’ equipment, information, policies, and professional staff. These findings underscore the importance of a multidimensional assessment approach that goes beyond the assessment of only the built environment. Some of the most difficult items pertained to the availability of adaptive exercise equipment, power-assisted doors, audible cues in elevators, and provision of information in alternate formats, all of which are associated with added costs. This is particularly true in cases in which structural changes are required to existing structures, such as improving access to an elevator system. However, cost issues were not the only barriers to making improvements in facility access. Although staff members working in health clubs appeared to respond favorably to questions related to professional behavior towards persons with disabilities, it is difficult to ascertain whether these responses would parallel actual experiences of working directly with persons with disabilities. Nonetheless, some items on the professional behavior subscale seemed to indicate the presence of negative attitudes, such as staff members feeling uncomfortable with persons with disabilities and directing their interactions to personal assistants rather than to the person with a disability.

It is important for owners and managers of fitness centers and health clubs to be aware of their facility’s level of accessibility.9,16,27 Barriers to outdoor physical activity environments for people with disabilities magnify the importance of providing accessible and disability-friendly indoor exercise settings. Previous research has reported that the condition of sidewalks and the number of known walking/ jogging paths and bicycling routes have been found to be associated with increased physical activity behavior among the general population.23 For people who have mobility or visual disabilities involving paralysis or weakness, balance impairments, limited/no vision or joint pain, walking as a primary mode of exercise or performing other forms of outdoor physical activity (e.g., yard work, gardening, and cycling) is not always possible. Therefore, indoor fitness facilities and health clubs may be the only viable choice for some individuals in terms of increasing their level of physical activity.

The ADA provides the legal foundation for ensuring the accessibility of community areas for people with disabilities, including both publicly and privately owned fitness and recreation facilities. For example, these facilities are obligated to provide accessible parking, access routes, and bathrooms. However, the present Americans with Disabilities Act Guidelines lack enforceable requirements concerning other areas and features of health clubs, including locker rooms, exercise equipment areas, swimming pools, fitness center policies and procedures, and programs. To address this concern, the US Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board has recently finalized a set of guidelines for the accessibility of various types of fitness and recreational venues.28 It is anticipated that these guidelines will be fully integrated into the ADAAG guidelines as enforceable regulations within the next 2–4 years and will be a starting point for fitness centers and health clubs to devote more attention to the needs of individuals with disabilities.

Additional data are needed to provide a more precise picture of the level of accessibility of health clubs and fitness centers and to provide accurate normative information for future benchmarking. Future efforts toward this end may help to improve access to health clubs for people with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Division of Human Development and Disability (grant R04/ CCR518810), and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (grant H133E020715).

Human Participant Protection The study was approved by the Office for the Protection of Research Subjects, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors J. H. Rimmer developed the conceptual framework and design of the study. B. Riley conducted the statistical analyses. E. Wang assisted in the design and analysis of the study. A. Rauworth directed and organized data collection.

References

- 1.McNeil JM. Americans with disabilities 1994–1995. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics, and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census; 1997. Current population reports 1999: Series P70;61: 3–6.

- 2.Raina P, Dukeshire S, Lindsay J, Chambers LW. Chronic conditions and disabilities among seniors: an analysis of population-based health and activity limitation surveys. Ann Epidemiol. 1998;8:402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heath G, Fentem P. Physical activity among persons with disabilities: a public health perspective. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1997;25:195–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rimmer J, Braddock D. Physical activity, disability and cardiovascular health. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1997.

- 5.Rimmer J, Rubin S, Braddock D, Hedman G. Physical activity patterns in African-American women with physical disabilities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999; 31:613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuifbergen AK, Roberts GJ. Health promotion practices of women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1997;78(suppl 5):S3–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US. Department of Health and Social Services, Healthy People 2010, Volume II, Conference Edition. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed April 10, 2002.

- 8.Coyle CP, Santiago M, Shank JW, Ma GX, Boyd R. Secondary conditions and women with physical disabilities: a descriptive study. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000;81: 1380–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lollar DJ, ed. Preventing Secondary Conditions Associated with Spina Bifida or Cerebral Palsy: Proceedings and Recommendations of a Symposium. Washington, DC: Spina Bifida Association of America; 1994.

- 10.Turk MA, Scandale J, Rosenbaum PF, Weber PJ. The health of women with cerebral palsy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2001;12:153–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilber N, Mitra M, Walker DK, Allen DA, Meyers AR, Tupper P. Disability as a public health issue: findings and reflections from the Massachusetts survey of secondary conditions. Milbank Q. 2002;80:393–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardinal BJ, Spaziani MD. ADA compliance and the accessibility of physical activity facilities in western Oregon. Am J Health Promot. 2003;17:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nary DE, Froehlich AK, White GW. Accessibility of fitness facilities for persons with disabilities using wheelchairs. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2000;6:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rimmer J, Riley BB, Wang E, Rauworth AE, Jukowksi J. Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities: barriers and facilitators. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rimmer J, Rubin S, Braddock D. Barriers to exercise in African-American women with physical disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thierry J. Promoting the health and wellness of women with disabilities. J Womens Health. 1998;7: 505–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rejeski J, Focht B. Aging and physical disability: on integrating group and individual counseling with the promotion of physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2002; 30:166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Healthy People 2010 working draft. Chapter 6: Disability and Secondary conditions. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1999.

- 19.Brownson RC, Baker EA, Houseman RA, Brennan LK, Bacak SJ. Environmental and policy determinants of physical activity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1995–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humpel N, Owen N, Leslie E. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical activity: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:188–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owen N, Leslie E, Salmon J, Fotheringham NJ. Environmental determinants of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallis J, Kraft K, Linton LS. How the environment shapes physical activity: a transdisciplinary research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharpe PA, Granner ML, Huto B, Ainsworth BE. Association of environmental factors to meeting physical activity recommendations in two South Carolina counties. Am J Health Promot. 2004;18:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimmer J, Riley BB, Wang E, Rauworth AE. An instrument that measures the accessibility of fitness and recreation environments for persons with disabilities—AIMFREE. Disabil Rehabil. 26;1087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Schumacker RE. Rasch measurement using dichotomous scoring. J Appl Meas. 2004;5:328–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Figoni SF, McClain L, Bell AA, Degan J, Norbury N, Rettele R. Accessibility of physical fitness facilities in the Kansas City metropolitan area. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 1998;5:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick D. Rethinking prevention for people with disabilities. Part I: A conceptual model for promoting health. Am J Health Promot. 1997;11:257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Access Board. Accessibility guidelines for recreation facilities: an overview. Available at: http://www.access-board.gov/recreation/final.htm. Accessed August 9, 2004.