Abstract

Objectives. We examined the association between pain-related activity difficulty (PRAD) in the past 30 days and health-related quality of life, health behaviors, disability indices, and major health impairments in the general US population.

Methods. We obtained data from 18 states in the 2002 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an ongoing, cross-sectional, state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey of noninstitutionalized adults aged 18 years or older.

Results. Nearly one quarter of people in the 18 states and the District of Columbia reported at least 1 day of PRAD in the past 30 days. PRAD was associated with obesity, smoking, physical inactivity, impaired general health, infrequent vitality, and frequent occurrences of physical distress, mental distress, depressive symptoms, sleep insufficiency, and anxiety symptoms. Moreover, a general dose–response relationship was noted between increased days of PRAD and increased prevalence of impaired health-related quality of life, disability indices, and health risk behaviors.

Conclusion. Pain negatively influences various domains of health, not only among clinical populations, but also in the general community, suggesting a critical need for the dissemination of targeted interventions to enhance recognition and treatment of pain among adult community-dwellers.

Pain has been defined as an unpleasant sensory or emotional experience associated with potential or actual tissue damage.1 Chronic pain affects about 90 million Americans2 and nearly half of the US population sees a physician primarily because of pain each year.3 Pain may manifest in a variety of ways including acute events (e.g., injury), chronic episodic conditions (e.g., migraine headaches), and chronic persistent problems (e.g., arthritis)4 and may be neurogenic or psychogenic in nature.5

Notably, people who live with persistent pain are 4 times more likely than those without pain to suffer from depression or anxiety and more than twice as likely to have difficulty working.6 Conditions associated with pain cost US companies approximately $61.2 billion per year, primarily because of impaired work performance.4 In addition, pain accounts for 20% of medical visits and 10% of prescription drug sales.7 In declaring 2001 to 2011 to be the “Decade of Pain Control and Research,” Congress provided much-needed recognition of this frequently chronic and potentially disabling condition.8,9

Pain is widely accepted as one of the most important determinants of quality of life because of its widespread adverse effects, including diminishing mental health and well-being and impairing the individual’s ability to perform daily activities.3 Although numerous studies have examined the association between pain and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in countries outside the United States and in clinical populations suffering from specific conditions, no studies were found examining associations between days of pain-related activity difficulty (PRAD), HRQOL, health behaviors, disability indices, and major impairments among US community-dwellers. To examine these associations, data were analyzed from the 2002 survey of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

METHODS

The BRFSS is an ongoing, state-based, cross-sectional, random-digit-dialed telephone survey of noninstitutionalized adults aged 18 years or older in the United States, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. It monitors the prevalence of key health- and safety-related behaviors and characteristics.10 Trained interviewers collect data on a monthly basis by means of an independent probability sample of households with telephones among the US population.10 Data from all states are pooled to produce national estimates.10 In 2002, trained interviewers administered standardized HRQOL questions in 18 states (Alabama, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Virginia, and Wisconsin) and the District of Columbia. BRFSS methods, including its weighting procedure, are described elsewhere.11

Survey participants’ responses to 8 HRQOL questions with demonstrated validity and reliability for population health surveillance12 were examined. Respondents were asked to rate their general health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. These responses were dichotomized into (1) excellent, very good, or good and (2) fair or poor. The remaining 7 questions asked respondents to estimate the frequency of various conditions during the previous 30 days: “How many days was your physical health, which includes physical illness or injury, not good?” (physical distress); “How many days was your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, not good?” (mental distress); “How many days did you feel sad, blue, or depressed?” (depressive symptoms); “How many days did you feel worried, tense, or anxious?” (anxiety symptoms); “How many days did you feel you did not get enough rest or sleep?” (sleep insufficiency); “How many days have you felt very healthy and full of energy?” (vitality); and “How many days did pain make it difficult to do your usual activities?” (PRAD). With the exception of the PRAD question, responses were dichotomized into 0 to 13 (infrequent) and 14 to 30 (frequent) unhealthy days in each domain, or, in the case of vitality, healthy days. This dichotomy has been used in previous research,13–15 with the term “frequent” representing the respondent’s status for a substantial portion of the month. PRAD days were categorized into 0 days (no PRAD), 1 to 13 days (infrequent PRAD), and 14 to 30 days (frequent PRAD). Specifically, this study examined the association of these 3 PRAD categories with the 7 other HRQOL measures.

The BRFSS also asks respondents questions about their smoking status, physical activity, height and weight, and alcohol consumption. A current smoker was defined as someone who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and who indicated they are presently a smoker. People were considered to be physically inactive if they did not participate in any leisure time physical activity or exercise during the previous 30 days. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. People were considered obese if their body mass index was ≥ 30 kg/m2. Men were considered heavy drinkers if they drank more than 2 drinks per day, while women were considered heavy drinkers if they drank more than 1 drink per day.16

The HRQOL module also contains a section on disability. To investigate the association between PRAD and disability, we examined the prevalence and odds of disability among the 3 levels of PRAD. To be included in this analysis, the respondent must first have answered “yes” or “no” to both of the following questions: “Are you limited in any way in any activities because of physical, mental, or emotional problems?” or “Do you have a health problem that requires you to use special equipment, such as a cane, a wheelchair, a special bed, or a special telephone?” People who responded “yes” to either question were considered to have a disability.17 Among those with a disability, an examination of the prevalence and odds of personal care and routine needs assistance by PRAD category was conducted.

In addition, among those with a disability, we assessed the prevalence of PRAD by reported primary impairment or health problem. For this subanalysis, respondents with a disability were asked: “What is your major impairment or health problem?” Discrete categories to which the interviewer assigned participants’ responses include: arthritis/rheumatism, back/neck problems, fractures, bone/joint injury, walking problem, lung/ breathing problem, hearing problem, eye/vision problem, heart problem, stroke problem, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, depression/anxiety/ emotional problem, and other impairments/ problem. Respondents could indicate only 1 primary impairment.

Of the 84 904 respondents in the 18 states and the District of Columbia, 5098 (6.0%) were excluded because of missing information for study variables (1457 because of missing sociodemographic information, 3641 because of missing PRAD data), yielding data from 79 806 respondents available for analysis. For the disability subanalysis, a total of 79 356 respondents provided sufficient information to determine disability status. Of these, 14 814 were considered to have a disability. A primary impairment or health problem was reported by 14 252 of these respondents.

SUDAAN software (version 9; Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) was used in the analyses to account for the complex sample design and to calculate prevalence estimates, standard errors, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), unadjusted odds ratios, and adjusted odds ratios. All statistical inferences were based on a significance level of P < .05. Unconditional logistic regression analysis was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios and conditional marginals. All adjusted models contained gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and employment status.

RESULTS

Nearly one quarter of people in the 18 states and the District of Columbia reported at least 1 day of PRAD in the past 30 days; 15.6% (95% CI = 15.1, 16.1) reported infrequent PRAD, and 9.3% (95% CI = 9.0, 9.7) reported frequent PRAD. Associations between PRAD days and sociodemographic characteristics are listed in Table 1 ▶. People aged 18 to 24 years were less likely to report frequent PRAD than those aged 25 years or older. Moreover, women were significantly more likely to report frequent PRAD than men, whereas White non-His-panic respondents were more likely to report frequent PRAD compared with Black non-Hispanic or Hispanic respondents. Additionally, people with less than a high-school education were more likely to report frequent PRAD than those with greater than a high-school education, whereas those previously married were significantly more likely to report frequent PRAD than those currently married. Finally, people who were unemployed, unable to work, retired, or a student or homemaker were significantly more likely to report frequent PRAD than those currently employed.

TABLE 1—

Prevalence and Adjusted Odds of Pain-Related Activity Difficulty (PRAD), by Selected Sociodemographic Characteristics: 2002

| No PRAD days (0 days in past 30) | Infrequent PRAD (1–13 days in past 30) | Frequent PRAD (14–30 days in past 30) | ||||

| Characteristic | % (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| 18–24 | 79.8 (77.9, 81.6) | 1.0 | 16.8 (15.1, 18.6) | 1.0 | 3.4 (2.7, 4.4) | 1.0 |

| 25–34 | 79.8 (78.4, 81.1) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) | 15.8 (14.6, 17.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | 4.4 (3.8, 5.1) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.2) |

| 35–44 | 74.7 (73.4, 76.0) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8) | 16.6 (15.6, 17.8) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 8.7 (7.8, 9.6) | 3.0 (2.2, 4.0) |

| 45–54 | 70.6 (69.1, 72.0) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 17.1 (16.0, 18.3) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.4) | 12.3 (11.3, 13.5) | 3.9 (2.9, 5.4) |

| 55–64 | 72.3 (70.7, 73.8) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.9) | 14.6 (13.3, 15.9) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 13.2 (12.1, 14.3) | 3.4 (2.5, 4.6) |

| 65–74 | 73.8 (72.0, 75.6) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 12.3 (11.1, 13.7) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.9) | 13.8 (12.5, 15.3) | 3.2 (2.3, 4.5) |

| ≥ 75 | 72.9 (70.7, 75.0) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 11.6 (10.3, 13.1) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.8) | 15.5 (13.7, 17.5) | 3.3 (2.3, 4.6) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 77.4 (76.5, 78.3) | 1.0 | 14.6 (13.9, 15.4) | 1.0 | 8.0 (7.5, 8.6) | 1.0 |

| Women | 72.9 (72.1, 73.7) | 0.8 (0.8, 0.9)d | 16.5 (15.9, 17.2) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | 10.6 (10.0, 11.2) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non- Hispanic | 74.2 (73.6, 74.8) | 1.0 | 15.9 (15.4, 16.4) | 1.0 | 9.9 (9.5, 10.3) | 1.0 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 76.4 (74.1, 78.4) | 1.3 (1.2, 1.5) | 15.1 (13.5, 17.0) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 8.5 (7.2, 10.1) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8) |

| Hispanic | 77.8 (75.2, 80.2) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.5) | 14.9 (13.0, 17.0) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 7.4 (5.8, 9.3) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) |

| Other b | 76.8 (74.1, 79.3) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.3) | 14.8(12.6, 17.2) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 8.4 (7.0, 10.1) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) |

| Education | ||||||

| < High-school graduate | 71.8 (69.6, 73.9) | 1.0 | 13.1 (11.7, 14.7) | 1.0 | 15.1 (13.4, 16.9) | 1.0 |

| High-school graduate | 74.0 (72.9, 75.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 15.5 (14.6, 16.4) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | 10.5 (9.9, 11.2) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) |

| > High-school graduate | 76.3 (75.6, 77.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | 16.2 (15.5, 16.9) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | 7.5 (7.0, 7.9) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Currently married | 76.7 (76.0, 77.5) | 1.0 | 14.6 (14.0, 15.3) | 1.0 | 8.7 (8.2, 9.2) | 1.0 |

| Previously marriedc | 68.2 (66.9, 69.5) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.8)d | 16.2 (15.2, 17.2) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | 15.6 (14.6, 16.7) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.4) |

| Never marriedc | 76.3 (74.8, 77.7) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 17.6 (16.4, 18.9) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.4) | 6.1 (5.4, 7.0) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 79.0 (78.3, 79.7) | 1.0 | 15.7 (15.1, 16.4) | 1.0 | 5.3 (5.0, 5.7) | 1.0 |

| Unemployed | 70.3 (67.2, 73.2) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 17.8 (15.5, 20.5) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | 11.9 (9.9, 14.2) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.1) |

| Unable to work | 26.6 (23.5, 30.0) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.1)d | 17.8 (15.3, 20.5) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 55.7 (52.0, 59.3) | 17.5 (14.7, 20.7) |

| Retired | 73.1 (71.7, 74.4) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8) | 13.2 (12.2, 14.3) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | 13.7 (12.7, 14.8) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.5) |

| Student/homemaker | 75.7 (73.9, 77.4) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 16.5 (15.0, 18.1) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.2) | 7.8 (6.9, 8.9) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.1) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted odds ratio.

aAdjusted by gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and employment status.

bAsian, non-Hispanic; Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic; American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic; other race, non-Hispanic; multirace, non-Hispanic.

cPreviously married includes those divorced, widowed, or separated; never married includes those never married and members of unmarried couples.

dPoint estimate is the same as either the upper or lower bound of the confidence interval because of rounding.

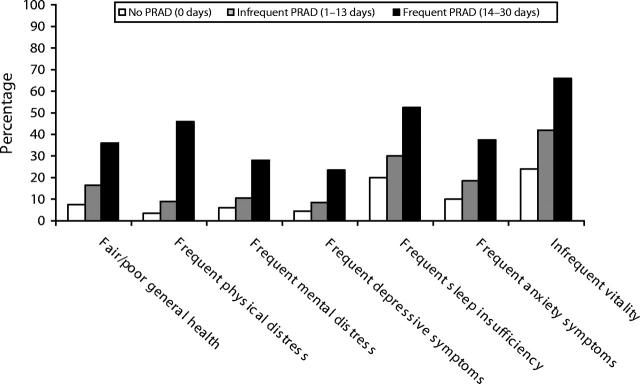

Chi-square tests revealed a significant relationship between PRAD and age, gender, education, employment status, marital status (P < .001), and race/ethnicity (P = .01). After adjustment for these covariates, we found a general dose–response relationship between increased PRAD days and increased prevalence of impaired HRQOL (Figure 1 ▶). For example, 7.6% (SE = 0.2) of people with no PRAD days in the past 30 days reported fair or poor general health, whereas 16.6% (SE = 0.7) of those with infrequent PRAD and 36.0% (SE = 1.2) of those with frequent PRAD reported fair or poor general health. This pattern was true for frequent physical distress (3.3% [SE = 0.2], 8.9% [SE = 0.7], and 45.8% [SE = 2.0]), frequent mental distress (6.2% [SE = 0.3], 10.3% [SE = 0.8], and 28.1% [SE = 1.8]), frequent depressive symptoms (4.6% [SE = 0.2], 8.5% [SE = 0.5], and 23.6% [SE = 1.1]), frequent sleep insufficiency (20.0% [SE = 0.3], 29.9% [SE = 0.8], and 52.6% [SE = 1.3]), frequent anxiety symptoms (10.1% [SE = 0.3], 18.4% [SE = 0.7], and 37.3% [SE = 1.2]), and infrequent vitality (23.9% [SE = 0.4], 42.0% [SE = 0.9], and 66.0% [SE = 1.2]).

FIGURE 1—

Adjusted prevalences of health-related quality of life indicators among US adults, by PRAD days in the past 30 days: 2002.

Note. PRAD = pain-related activity difficulty. Conditional marginals adjusted by gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and employment status.

Prevalence of smoking and obesity significantly increased as PRAD days increased (Table 2 ▶). Additionally, women reporting infrequent PRAD were significantly more likely to drink heavily than those with no PRAD days (adjusted odds ratio = 1.3); however, those reporting frequent PRAD were significantly less likely to drink heavily than those with infrequent PRAD (adjusted odds ratio = 0.5) and were equally as likely to drink heavily as those with no PRAD. Finally, people reporting frequent PRAD were significantly less likely than those reporting no PRAD or infrequent PRAD to be physically active (adjusted odds ratio = 2.0).

TABLE 2—

Prevalence, Unadjusted, and Adjusted Odds Ratios of Health Risk Behaviors and Obesity, by Pain-Related Activity Difficulty (PRAD): 2002

| Characteristic | No PRAD (95% CI) (0 days in past 30) | Infrequent PRAD (95% CI) (1–13 days in past 30) | Frequent PRAD (95% CI) (14–30 days of past 30) |

| Smoking | |||

| Percentage | 20.3 (19.7, 21.0) | 26.5 (25.0, 28.1) | 31.4 (29.5, 33.5) |

| OR | 1.0 | 1.4 (1.3, 1.6) | 1.8 (1.6, 2.0) |

| AORa | 1.0 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.5) | 1.7 (1.6, 1.9) |

| Heavy drinking (men) | |||

| Percentage | 6.6 (6.1, 7.3) | 7.4 (6.0, 9.1) | 6.8 (5.2, 8.8) |

| OR | 1.0 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) |

| AORb | 1.0 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) |

| Heavy drinking (women) | |||

| Percentage | 4.6 (4.2, 5.0) | 6.3 (5.2, 7.7) | 2.8 (2.1, 3.6) |

| OR | 1.0 | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) |

| AORb | 1.0 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.7) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) |

| Physical inactivity | |||

| Percentage | 21.8 (21.1, 22.5) | 22.2 (20.8, 23.6) | 43.1 (41.0, 45.3) |

| OR | 1.0 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 2.7 (2.5, 3.0) |

| AORa | 1.0 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 2.0 (1.8, 2.2) |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 | |||

| Percentage | 18.5 (17.9, 19.1) | 25.1 (23.6, 26.7) | 33.2 (31.2, 35.3) |

| OR | 1.0 | 1.5 (1.4, 1.6) | 2.2 (2.0, 2.4) |

| AORa | 1.0 | 1.5 (1.3, 1.6) | 1.9 (1.7, 2.1) |

Note. CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio; AOR=adjusted odds ratio.

aAdjusted by gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and employment status.

bAdjusted by age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and employment status.

The prevalence of disability increased as PRAD days increased; 8.1% (95% CI = 7.7, 8.5) for no PRAD days, 31.3% (95% CI = 29.6, 33.0) for infrequent PRAD days, and 68.6% (95% CI = 66.6, 70.6) for frequent PRAD days (Table 3 ▶). Adults reporting frequent PRAD were 16.7 times more likely to report a disability than those reporting no PRAD. Among adults with a disability and frequent PRAD, 20.0% required help with personal care activities, and 48.5% required help with routine needs such as household chores and shopping.

TABLE 3—

Prevalence, Unadjusted, and Adjusted Odds of Various Indices of Disability by Pain-Related Activity Difficulty (PRAD), 2002

| No PRAD (95% CI) (0 days in past 30) | Infrequent PRAD (95% CI) (1–13 days in past 30) | Frequent PRAD (95% CI) (14–30 days in past 30) | |

| Limitations because of physical, mental, or emotional problems | |||

| Percentage | 7.2 (6.8, 7.6) | 29.2 (27.6, 30.9) | 65.7 (63.6, 67.7) |

| OR | 1.0 | 5.3 (4.8, 5.9) | 24.7 (22.2, 27.5) |

| AORa | 1.0 | 5.4 (4.9, 6.0) | 16.0 (14.2, 18.0) |

| Use of special equipment | |||

| Percentage | 2.0 (1.8, 2.2) | 7.2 (6.3, 8.2) | 26.4 (24.5, 28.3) |

| OR | 1.0 | 3.9 (3.2, 4.6) | 17.9 (15.5, 20.7) |

| AORa | 1.0 | 4.1 (3.4, 4.9) | 9.9 (8.4, 11.7) |

| Disability b | |||

| Percentage | 8.1 (7.7, 8.5) | 31.3 (29.6, 33.0) | 68.6 (66.6, 70.6) |

| OR | 1.0 | 5.2 (4.7, 5.7) | 25.0 (22.4, 27.8) |

| AORa | 1.0 | 5.5 (5.0, 6.1) | 16.7 (14.7, 18.8) |

| Among people who reported disability | |||

| Requires help with personal care (e.g., eating, bathing, dressing, getting around the house) | |||

| Percentage | 4.0 (3.2, 4.9) | 7.8 (6.1, 10.0) | 20.0 (17.8, 22.4) |

| OR | 1.0 | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) | 4.3 (3.5, 5.4) |

| AORa | 1.0 | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) | 3.2 (2.6, 3.9) |

| Requires help with routine needs (e.g., household chores, shopping) | |||

| Percentage | 15.9 (14.1, 18.0) | 24.3 (21.4, 27.3) | 48.5 (45.8, 51.2) |

| OR | 1.0 | 1.6 (1.3, 2.0) | 4.6 (3.9, 5.4) |

| AORa | 1.0 | 1.8 (1.4, 2.2) | 3.4 (2.9, 4.1) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; AOR = adjusted odds ratio.

aAdjusted by gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and employment status.

b The respondent must have provided a response (yes, no) to the question regarding limitations because of physical, mental, or emotional problems and the question regarding use of special equipment to be included. Persons were considered to have a disability if they responded “yes” to at least 1 of the questions.

Table 4 ▶ displays the distribution of PRAD days among respondents reporting disability by primary impairment or health problem. With the exception of hearing problems, eye/vision problems, and lung/breathing problems, at least 50% of respondents with each disabling condition examined reported at least 1 day of PRAD in the past 30 days, and 20% or more of respondents with each condition reported frequent PRAD. More specifically, over 40% of those reporting back or neck problems, arthritis or rheumatism, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer reported frequent PRAD, whereas between 30% and 40% of respondents reporting disability related to walking problems, fractures or bone/joint injuries, strokes, heart problems, and depression, anxiety, or emotional problems reported frequent PRAD.

TABLE 4—

Prevalence of Pain-Related Activity Difficulty (PRAD) Among Persons Reporting Disabilityaby Primary Impairment or Health Problem: 2002

| n | No PRAD (0 days in past 30), % (95% CI) | Infrequent PRAD (1–13 days in past 30), % (95% CI) | Frequent PRAD (14–30 days of past 30), % (95% CI) | |

| Arthritis/rheumatism | 2234 | 23.4 (19.8, 27.5) | 31.5 (27.3, 36.1) | 45.1 (40.6, 49.6) |

| Back/neck problems | 2376 | 20.8 (18.1, 23.8) | 29.3 (25.7, 33.2) | 49.9 (46.0, 53.9) |

| Fractures, bone/joint injuries | 1155 | 28.7 (24.5, 33.3) | 34.3 (28.9, 40.0) | 37.0 (31.7, 42.7) |

| Walking problems | 1263 | 40.3 (34.8, 46.0) | 22.1 (17.5, 27.6) | 37.6 (31.8, 43.8) |

| Lung/breathing problems | 931 | 50.2 (44.1, 56.2) | 27.2 (21.9, 33.3) | 22.6 (18.5, 27.3) |

| Hearing problems | 130 | 82.5 (70.0, 90.6) | 9.5 (5.4, 16.3) | NAb |

| Eye/vision problems | 338 | 65.3 (55.0, 74.3) | 15.2 (9.3, 23.9) | 19.5 (12.8, 28.6) |

| Heart problems | 1188 | 46.9 (41.5, 52.5) | 22.9 (18.3, 28.3) | 30.2 (25.5, 35.2) |

| Stroke problems | 284 | 46.8 (36.0, 57.8) | 21.2 (13.2, 32.3) | 32.1 (23.6, 41.9) |

| Hypertension | 233 | 37.7 (27.2, 49.4) | 18.8 (11.7, 28.7) | 43.6 (31.2, 56.8) |

| Diabetes | 417 | 31.2 (23.6, 40.0) | 23.9 (16.5, 33.2) | 44.9 (36.5, 53.7) |

| Cancer | 274 | 35.0 (25.0, 46.5) | 21.5 (14.7, 30.3) | 43.6 (33.8, 53.9) |

| Depression/anxiety/emotional problems | 659 | 44.7 (37.0, 52.5) | 25.6 (19.3, 33.2) | 29.7 (22.6, 37.9) |

| Other impairment/problem | 2770 | 40.1 (36.6, 43.7) | 29.0 (25.8, 32.5) | 30.9 (27.9, 34.1) |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

aRespondent answered “yes” to at least one of the following questions: “Are you limited in any way in any activities because of physical, mental, or emotional problems?” or “Do you have a health problem that requires you to use special equipment, such as a cane, a wheelchair, a special bed, or a special telephone?” Additionally, both questions must contain a response (yes, no).

bRelative standard error > 30.

DISCUSSION

We found a general dose–response relationship between PRAD days and increased prevalence of impaired HRQOL, health risk behaviors, and disability indices. Our study corroborates the results of previous research indicating that pain is strongly related to impaired quality of life, both physically and mentally,18 in addition to being associated with low overall self-rated health and sleep impairment.19–21 Not only does PRAD have a significant impact on many domains of life, a sizable portion of the population is affected; approximately 1 of 5 men and 1 of 4 women in the 18 states and the District of Columbia reported at least 1 PRAD day in the past 30 days.

Notably, this study also indicates that people with disability who selected their primary impairment or health problem to be depression, anxiety, or emotional problems reported frequent PRAD at rates comparable to people reporting disability caused by cardiovascular conditions, such as heart problems and strokes. This psychological link to pain is important because research has suggested that psychological factors and coping skills may influence susceptibility to chronic pain and pain control.22–26 Notably, psychological factors may be more important than many physiological variables in the development of pain, particularly in people with back and neck pain.24 Previous research also suggests that psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression, can potentially decrease pain thresholds and increase functional impairment.27 Additionally, pain may increase the somatic symptoms of depression (fatigue, insomnia) in addition to affecting the duration and probability of recurrence of depressive illness.28

As has been reported previously in clinical samples and population studies conducted outside of the United States, pain was associated with female gender, unemployment, divorce, low educational attainment, and increased age.29–40 Given that the US population is rapidly aging,41 the association between age and pain is particularly noteworthy. Additionally, consistent with research conducted by Portenoy et al.34, which indicates that Whites experience pain for a longer duration but with less intensity than Black non-Hispanics or Hispanics, this study suggests that White non-Hispanic respondents were significantly more likely to report frequent PRAD than Black non-Hispanic or Hispanic respondents.

Notably, our results also indicate that the prevalence of frequent PRAD decreases with education, whereas infrequent PRAD is associated with higher educational attainment. It could be speculated that the inverse relationship between frequent PRAD and education may be linked to increased likelihood of having employment that may require physical exertion, an inability to seek medical care for pain management, or conversely, an inability to achieve advanced education as a result of pain-related disability. The increase of infrequent PRAD days with increased education may be attributable to sporadic pain sources such as tension headaches or stress-related musculoskeletal syndromes, which may be more prevalent among those with higher education because of job stress. Additionally, those who were unemployed, unable to work, retired, or homemakers or students were significantly more likely to report frequent PRAD than those currently employed. Notably those who were unable to work were 17.5 times more likely to report frequent PRAD than those employed. This finding, in combination with the high prevalence of disability among those with frequent PRAD (68.6%), emphasizes the significant association between frequency of pain and disability. Unfortunately, because of the cross-sectional design, we cannot determine the temporal sequence of PRAD with either work status or educational attainment. Future longitudinal studies are needed to investigate these aspects appropriately.

A significant association between PRAD days and behavioral risk factors such as smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity was also observed. Results of recent studies have suggested a possible relationship between cigarette smoking and back pain and various neurological, cardiovascular, and pulmonary disorders.42–44 In addition, studies indicate that physical inactivity and obesity are linked to sleep apnea, back pain, osteoarthritis, and gallstones as well as cancers of the colon, breast, uterus, and prostate–many of which are associated with pain.45 Reducing these risk behaviors may influence the quantity and intensity of pain for some people. For example, among adults with osteoarthritis, increasing physical activity has been shown to reduce pain in the long term. Subsequently, physical function improves and the risk of disability declines as people with osteoarthritis become more active.46–48

Chronic widespread pain in the community generally has a fair prognosis,33,49,50 with 1 US population-based study indicating a 32.5% recovery rate over an 8-year period.49 In this study, at least 45% of disabled respondents who reported back or neck problems or arthritis and rheumatism as their major impairment also reported frequent PRAD, despite the availability of evidence-based interventions reported to significantly reduce pain among people with these conditions. Various pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, including medications (muscle relaxants and non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs), therapeutic exercise programs, “back schools,” and spinal manipulative therapy, can successfully reduce pain among patients with back and neck pain.51 Among people with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions, self-management education and physical activity programs have yielded 20% to 25% reductions in pain in addition to improving mental health and physical functioning.52

There are several limitations to this study. First, because BRFSS is a telephone survey, it may disproportionately exclude people of low socioeconomic status, a population known to have a lower HRQOL and higher mortality rates than the general population.53 Second, after examining the sociodemographic characteristics of persons included in the analysis versus those excluded (including those in the 18 states and the District of Columbia who were missing data and those in the remaining states and territories), this analysis may not be entirely representative of the US population. Third, people with severely impaired physical or mental health might not be able to complete the survey and thus, may have been underrepresented. Fourth, these data are self-reported and were not validated by physical or psychiatric examination. However, as pain is a subjective experience, data assessing pain can only be gathered via self-report. Fifth, as the respondent could only select one primary impairment or health problem, an analysis of other potential pain-related comorbid conditions was not possible. Additionally, as the PRAD question was referenced to the past 30 days and does not contain information on its previous course, assessment of chronic pain was not possible. Finally, because the data were cross-sectional, examining potential causal relationships between PRAD days and HRQOL measures, health behaviors, and major impairments were not possible.

The results of this study indicate that PRAD is common in the general community and strongly associated with impaired HRQOL, adverse health behaviors, and disability indices—each of which may complicate efforts to treat the underlying precipitant of pain. Furthermore, in an analysis of people with disability, those reporting that their major impairment or health problem was depression, anxiety, or emotional problems were as likely to report frequent PRAD as those reporting cardiovascular conditions. These results are particularly noteworthy because they were obtained in a population-based survey and not from patients seeking clinical evaluation or treatment, suggesting a critical need for the dissemination of targeted interventions to reduce pain. The development of public health initiatives—targeting diverse constituencies and varied diseases and conditions—could be vital in increasing recognition of both the public health and clinical importance of pain and fostering interventions that improved pain control.

Acknowledgments

We thank the state Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System coordinators for their participation in data collection for this analysis and the Behavior Surveillance Branch staff for their assistance in developing the database.

Human Participant Protection This study has been approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention internal review board (protocol 2988) as meeting the criteria for appropriate consent in survey research.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors T. W. Strine originated the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the article. J. M. Hootman provided subject area expertise in the fields of pain and arthritis. D. P. Chapman provided editorial expertise. C. A. Okoro provided analytic expertise. L. S. Balluz provided eidtorial support for the project and helped in the acquisition of data.

References

- 1.IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain terms: a list of definitions and notes on usage. Pain. 1979;6: 249–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Study links chronic pain to signals in the brain. Tuesday, January 7, 2003. Available at: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/news_and_events/news_articles/news_article_chronic_pain.htm. Accessed August 16, 2005.

- 3.Katz N. The impact of pain management on quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2002;24(1 suppl): S38–S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost because of common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA. 2003;290:2443–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NINDS chronic pain information page. Available at: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/chronic_pain/chronic_pain.htm. Accessed August 16, 2005.

- 6.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization Study in primary care. JAMA. 1998;280:147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Max MB. How to move pain and symptoms research from the margin to the mainstream. J Pain. 2003;4:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Pain Society. In the news: decade of pain control and research: now is the time to do something about America’s pain crisis. Available at: http://www.ampainsoc.org/decadeofpain/news/092403.htm. Accessed August 16, 2005.

- 9.American Pain Society.Decade of pain control and research. Available at: http://www.ampainsoc.org/decadeofpain. Accessed August 16, 2005.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System User’s Guide. Atlanta, Ga: US. Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/pubrfdat.htm#users. Accessed August 16, 2005.

- 11.Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment: recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(RR-9):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Kobau R. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s healthy days measures—population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2003;1:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strine TW, Chapman DP, Kobau R, Balluz L, Mokdad A. Depression, anxiety, and physical impairments and quality of life in the US. noninstitutionalized population. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1408–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strine TW, Chapman DP. Associations of frequent sleep insufficiency with health-related quality of life and health behaviors. Sleep Med. 2005;6:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strine TW, Okoro CA, Balluz L, et al. Health-related quality of life and health risk behaviors among smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The dietary guidelines for Americans, 2000. 5th ed. US Department of Agriculture and the US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.usda.gov/cnpp/dietary_guidelines.html. Accessed August 16, 2005.

- 17.Okoro CA, Hootman JM, Strine TW, Balluz LS, Mokdad AH. Disability, arthritis, and body weight among adults aged 45 and older. Obes Res. 2004;12: 854–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergman S, Jacobsson LT, Herrström P, Petersson IF. Health status as measured by SF-36 reflects changes and predicts outcome in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a 3-year follow up study in the general population. Pain. 2004;108:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mäntyselkä PT, Turunen JH, Ahonen RS, Kumpusalo EA. Chronic pain and poor self-related health. JAMA. 2003;290:2435–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday L, Cleeland C. Impact of pain on self-rated health in the community-dwelling older adults. Pain. 2002;95:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson KC II, Mannes A. Persistent pain management for improved quality of life. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(5 suppl 1):S30–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo X, Edwards CL, Richardson W, Hey L. Relationships of clinical, psychologic, and individual factors with the functional status of neck pain patients. Value Health. 2004;7:61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillette RD. Behavioral factors in the management of back pain. Am Fam Phys. 1996;53:1313–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linton SJ. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine. 2000;25:1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercado AC, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Côté P. Coping with neck and low back pain in the general population. Health Psycho. 2000;19:333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McWilliams LA, Goodwin RD, Cox BJ. Depression and anxiety associated with three pain conditions: results from a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2004;111:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epker J, Block AR. Presurgical psychological screening in back pain patients: a review. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohayon MM. Specific characteristics of the pain/ depression association in the general population. J Clin Psychiatr. 2004;65(suppl 12):5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerdle B, Bjork J, Henriksson C, Bengtsson A. Prevalence of current and chronic pain and their influences upon work and healthcare-seeking: a population study. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1399–1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rustøen T, Wahl AK, Hanestad BR, Lerdal A. Paul S, Miaskowski C. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain in the general Norwegian population. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksen J, Jensen MK, Sjøgren P, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK. Epidemiology of chronic nonmalignant pain in Denmark. Pain. 2003;106:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rustøen T, Wahl AK, Hanestad BR, Lerdal A, Paul S, Miaskowski C. Gender differences in chronic pain—findings from a population-based study of Norwegian adults. Pain Manag Nurs. 2004;5:105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eriksen J, Ekholm O, Sjøgren P, Rasmussen NK. Development of and recovery from long-term pain. A 6-year follow-up study of a cross-section of the adult Danish population. Pain. 2004;108:154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Portenoy RK, Ugarte C, Fuller I, Haas G. Population-based survey of pain in the United States: differences among white, African American, and Hispanic subjects. J Pain. 2004;5:317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Scherstén B. Impact of chronic pain on health care seeking, self care, and medication. Results from a population-based Swedish study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999; 53:503–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith BH, Elliott AM, Chambers WA, Smith WC, Hannaford PC, Penny K. The impact of chronic pain in the community. Fam Prac. 2001;18:292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, Wilkie R, Croft PR. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Stafford Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain. 2004;110:361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bassols A, Bosch F, Campillo M, Canellas M, Banos JE. An epidemiological comparison of pain complaints in the general population of Catalonia (Spain). Pain. 1999;83:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergh I, Steen G, Waern M, et al. Pain and its relation to cognitive function and depressive symptoms: a Swedish population study of 70-year-old men and women. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2003;26:903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miaskowski C. The impact of age on a patient’s perception of pain and ways it can be managed. Pain Manag Nurs. 2000;1(3 suppl 1):2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldberg MS, Scott SC, Mayo NE. A review of the association between cigarette smoking and the development of nonspecific back pain and related outcomes. Spine. 2000;25:995–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leboeuf-Yde C.Smoking and lower back pain: a systematic literature review of 41 journal articles reporting 47 epidemiologic studies. Spine. 1999;24:1463–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das SK. Harmful health effects of cigarette smoking. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253(1–2):159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rissanen A, Fogelholm M. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of other morbid conditions and impairments associated with obesity: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exer. 1999; 31(suppl 11):S635–S645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the role of exercise in the management of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee—the MOVE consensus. Rheumatol. 2005;44:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fransen M, McConnell S, Bell M. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2003. Oxford, England: Update Software. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Van Baar ME, Assendelft WJ, Dekker J, Oostendorp RA, Bijlsma JW. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(7):1361–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magni G, Marchetti M, Moreschi C, Merskey H, Luchini SR. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and depressive symptoms in the National Health Nutrition Examination. I. Epidemiologic follow-up study. Pain. 1993; 53:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacFarlane GJ, Thomas E, Papageorgiou AC, Schollum J, Croft PR, Silman AJ. The natural history of chronic pain in the community: a better prognosis than in the clinic? J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1617–1620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997;22:2128–2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brady TJ, Kruger J, Helmick CG, Callahan LF, Boutaugh ML. Intervention programs for arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30: 44–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franks P, Gold MR, Fiscella K. Sociodemographics, self-rated health, and mortality in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:2505–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]