Abstract

Objectives. We examined the prevalence, characteristics, and responsibilities of young adults aged 18 to 25 years who are caregivers for ill, elderly, or disabled family members or friends.

Methods. We analyzed 2 previously published national studies (from 1998 and 2004) of adult caregivers.

Results. Young adult caregivers make up between 12% and 18% of the total number of adult caregivers. Over half are male, and the average age is 21. Most young adults are caring for a female relative, most often a grandmother. Young adult caregivers identified a variety of unmet needs, including obtaining medical help, information, and help making end-of-life decisions.

Conclusions. Analysis of these 2 surveys broadens our understanding of the spectrum of family caregivers by focusing on caregivers between the ages of 18 and 25 years. The high proportion of young men raises questions about the appropriateness of current support services, which are typically used by older women. Concerted efforts are essential to ensure that young adults who become caregivers are not deterred from pursuing educational and career goals.

Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, family caregiving, an age-old practice, became a major research, programmatic, and policy topic in the United States. Studies have focused primarily on adult children caring for elderly parents and older spousal caregivers, who make up the majority of the millions of adults who provide care. They are also the most likely to come to the attention of health care and social service providers.

Even as subpopulations are studied (e.g., by ethnicity, disease category, or relationship to the care recipient), one group, young adult caregivers aged 18 to 25 years, has been almost totally ignored. Even in the United Kingdom, where child caregivers, called “carers,” up to age 18 are counted in the census and are served through a variety of programs, young adults are only now beginning to be recognized. Becker1 estimates that there are almost 200 000 young adult caregivers aged 18 to 24 years in England and Wales.

This neglected group is important, because young adults are at a critical developmental stage. They have passed the turbulence of early and mid-adolescence, but most have not yet solidified life plans and choices; for many, education extends into their 20s, and marriage and childbearing typically occur at older ages. Arnett2 calls ages 18 to 25 the years of “emerging adulthood . . . a distinct period” of frequent changes, distinguished by “relative independence from social roles and normative expectations . . . the most volitional years of life” (emphasis in original).

Beyond memoirs and other retrospective accounts, we do not know how family caregiving—with its complex web of responsibilities, close relationships, burdens, and rewards—affects young adults or how these impacts, both positive and negative, differ by gender, ethnicity, relationship, and other factors. This article is a first step in describing the population, laying the groundwork for future studies.

Literature Review

The family caregiving literature is vast and growing, but only a few articles specifically address young adult caregivers. Shifren3 and Shifren and Kachorek4 reported on 24 individuals aged 21 to 58 years who had been caregivers while under the age of 21. The participants, recruited mainly through advertisements in caregiving organization newsletters, reported more positive than negative mental health, although 42% had high depressive scores. Dellmann-Jenkins et al.5 interviewed 47 individuals aged 18 to 40 years who were caring for a parent or grandparent. These participants, recruited mainly from social service and health care providers, reported both positive outcomes (e.g., long-lasting memories, acquiring a sense of self-respect, and preventing nursing home placement) and negative ones (e.g., less time for themselves, difficulty with marriage and dating partners, and job problems, including an inability to relocate). When asked what formal services would be most helpful, they cited emotional support from others of the same age.

METHODS

With such a paucity of data, very little can be said with confidence about this population. Yet, the population exists, as we initially learned through focus groups, conferences, and other encounters. We did not seek out young adult caregivers; they found us, typically asking about services for people their own age.

To begin to understand the prevalence and parameters of young adult caregiving, we analyzed data on caregivers aged 18 to 25 years from 2 national surveys of adult caregivers: one conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health, the United Hospital Fund, and the Visiting Nurse Service of New York (hereafter Harvard/UHF/VNS study)6 and the second by the National Alliance for Caregiving and the Association for the Advancement of Retired Persons (hereafter NAC/AARP study).7

Both were random, digit-dialed telephone surveys with similar screening methods and similar sample size (Harvard/UHF/VNS, 1002; NAC/AARP, 1247). Both used a broad definition of caregiving; the Harvard/UHF/VNS definition, for example, was: “Anybody who provides unpaid or arranges for paid or unpaid help to a relative or friend because they have an illness or disability that leaves them unable to do some things for themselves or because they are getting older.”

Some limitations should be noted at the outset. All surveys of this type are subject to sampling error, estimated in these surveys as ±2.8% to 3%. Nonsampling errors, such as nonresponse bias, coverage error, item response bias, and question order were minimized by the survey organizations through extensive pretesting and interviewer training. Although both surveys covered roughly the same ground, some questions were asked in different ways. Recent immigrant families were probably underrepresented; it is possible that young adults in households where they are the primary English speaker are more likely to be caregivers or have different patterns of caregiving than those in more established groups.

We emphasize that neither survey was designed specifically to gather data about this age group. Furthermore, although some of the findings about gender, race/ethnicity, and primary/nonprimary caregivers are intriguing, the numbers are small, and additional analysis is needed to determine whether any differences are significant. Finally, an extensive analysis of this group compared with other age groups is beyond the scope of this article, although we note a few general findings where appropriate.

RESULTS

Although, in most respects, data from the 2 surveys are comparable, there are 2 respects in which they differ and that warrant additional study. The Harvard/UHF/VNS study found a prevalence of 18% (n = 184), whereas the NAC/AARP study found 12% (n = 150). The percentage of young adult caregivers is similar, in fact, to the percentage of caregivers aged 65 years and older (13%) in the Harvard/UHF/VNS study. A recent survey of more than 16000 bank employees found that 12% of those reporting caregiving responsibilities for an ill child, parent, or other relative (10.6% of the total) were under the age of 25 years.8

Extrapolated to the US population in the years the surveys were conducted, there are from 3.9 million (2003) to 5.2 million (1998) young adult caregivers. Using 2000 US Census data, the estimates are 3.6 million to 5.5 million.9

The second major difference is that the Harvard/UHF/VNS study found a higher percentage of male caregivers (74.5%) than the NAC/AARP study (51%). Note that these are weighted data; the unweighted Harvard/UHF/VNS data are 57.3% males and 42.7% females, which are closer to the NAC/AARP results. Even this lower figure may be surprising, because, in the older age groups, women predominate, and caregiving is still typically treated as a woman’s concern. Among even younger caregivers (children aged 8 to 18 years), in a national survey, boys and girls were equally represented,10 and 1 small study among children in grades 6 to 12 found a high percentage of boys represented.11

The average age of the caregivers in both surveys was just over 21 years, and both were representative in terms of race/ethnicity (e.g., 15% Hispanic and 14% to 16% Black). (In each case in this and the following statistics, the Harvard/UHF/VNS study is cited first.) Educational levels varied somewhat. Although about a third (29.3% and 32%) reported some college experience, an overall a higher percentage of the NAC/AARP sample had graduated from college (18.9% vs 6.4%), whereas the Harvard/UHF/VNS sample had a higher percentage of high school-only graduates (47% vs 34.8%). In both samples, just under a half (49.9% and 44.4%) were employed full-time, and more than one fourth (28.1% and 28.5%) were students. Although most young adult caregivers reported being in excellent, very good, or good health, 8.4% in the Harvard/UHF/VNS study and 4.3% in the NAC/AARP study reported fair or poor health (Table I ▶).

TABLE 1—

Demographic Composition of Young Adult (18 to 25 Years) Caregivers in the United States

| Harvard/UHF/VNS, 1998 (n = 84) | NAC/AARP, 2004 (n = 50) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 74.5% | 50.8% |

| Female | 25.5 | 49.2 |

| Age | ||

| 18 | 13.8 | 15.6 |

| 19 | 10.8 | 11.5 |

| 20 | 16.8 | 9.9 |

| 21 | 18.4 | 12.8 |

| 22 | 13.5 | 18.6 |

| 23 | 10.9 | 6.8 |

| 24 | 7.8 | 15.9 |

| 25 | 7.8 | 9.0 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 13.6 | 16.4 |

| Hispanic | 14.7 | 14.5 |

| White/other | 71.7 | 69.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 11.2 | 24.8 |

| Widowed | 2.5 | n/a |

| Divorced | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| Separated | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| Single | 84.0 | 60.4 |

| Living with partner | n/a | 11.5 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 16.8 | 9.1 |

| High School graduate/GED | 47.5 | 34.8 |

| Some college | 29.3 | 32.0 |

| Technical school | n/a | 0.6 |

| College graduate | 6.4 | 18.9 |

| Graduate school/graduate work | n/a | 4.5 |

| Employment | ||

| Full time | 49.9 | 44.4 |

| Part time | 12.6 | 14.7 |

| Unemployed | 5.0 | 12.1 |

| Student | 28.1 | 28.5 |

| Other | 4.3 | 0.3 |

| Income, $ | ||

| < 20 000 (UHF) vs 15 000 (NAC) | 45.9 | 19.3 |

| 20–35 000 (UHF) vs 15–29 000 (NAC) | 23.7 | 30.5 |

| 35–75 000 (UHF) vs 30–75 000 (NAC) | 15.9 | 26.9 |

| > 75 000 | 14.5 | 16.3 |

| Caregiver health status | ||

| Excellent | 46.2 | 32.7 |

| Very good | 31.7 | 36.8 |

| Good | 13.8 | 26.0 |

| Fair | 5.9 | 3.1 |

| Poor | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Lives with recipient | 25.6 | 18.5 |

Notes. Harvard/UHF/VNS = Harvard School of Public Health/United Hospital Fund/Visiting Nurse Service of New York; NAC/AARP = National Alliance for Caregiving and Association for the Advancement of Retired Persons; GED = graduate equivalency diploma.

In both surveys, young adults were caring for a female (65.8% and 59.4%), more often a grandmother (42.2% and 24.1%) than a mother (7.4% and 15.4%). Young adults were, in general, caring for someone 2 generations older, whereas adults aged 26 to 64 years were caring for their parents’ generation, and caregivers aged 65 years and older were caring for spouses and other relatives of their own generation. There are, of course, exceptions; some young adults care for siblings, parents, partners, or friends.

The care recipients had many health problems. Close to half (44.6%) in the Harvard/UHF/VNS study had been hospitalized in the previous year, and about a third (32.1%) in the NAC/AARP study were disabled, 14.6% were “sick,” and 17.8% were frail.

In most cases, the young adult was not the primary caregiver (described as the person who “provides most of the care recipient’s care”). Caregivers in older age groups, particularly those aged 65 years and older, were more likely to be primary caregivers than were young adults. About three quarters of the young adults in each survey reported that another person provided most of the care; however, a substantial minority (23.5% in the Harvard/UHF/VNS survey and 15.7% in the NAC/AARP survey) reported that they provided most of the care. An additional 8.4% in the NAC/AARP survey reported that they split the care. Very few in either survey reported the presence of paid help.

Many of the young adult caregivers in both studies had been caregiving for a long time: 38.7% and 28% for 1 to 4 years; 19.2% and 14.5% for 5 to 9 years, and 8.7% and 5.5% for 10 years or more. Although the surveys captured a point in time, many of these young adults had started caregiving as young teenagers or children. Over a third in the Harvard/UHF/VNS study provide 8 to 20 hours of care a week, and 25.4% in the NAC/AARP study provided 9 to 20 hours of care. (The average for all adults in the Harvard/UHF/VNS study was 20.5 hours per week.) Similar percentages (23.6% and 20.7% provided 21 or more hours of care per week—more than the equivalent of a half-time job.

Young adult caregivers perform the same tasks as older caregivers, although they are less likely than older caregivers to do the most intimate kinds of personal care. In both surveys almost all the young caregivers (98.2% and 99.8%) reported providing help with instrumental activities of daily living. The most common tasks were shopping, housework, transportation, and meal preparation, although more than half (53.2%) in the NAC/AARP study reported managing finances, and 16.5% said that they arranged services. In the Harvard/UHF/VNS survey, 11.7% reported that they managed finances, and 8.3% said that they arranged government services.

About half (53.1% and 50.4%) reported providing activities of daily living (ADL) care, such as bathing, toileting, feeding, and dressing. The most common ADLs reported were helping the care recipient to get out of bed (about 39%), dressing (27%), and toileting (23.3%, per the NAC/AARP study). In both surveys, caregivers reported that the care recipient needed assistance in taking medications, which could be pills, injections, or other regimens (26.8% and 37.5%).

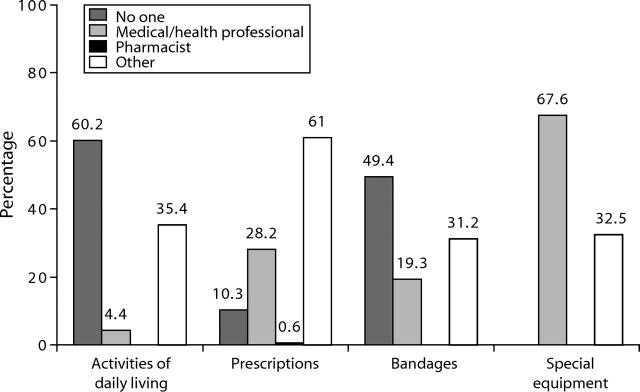

The Harvard/UHF/VNS survey asked about instruction for caregiving tasks. More than 60% reported that no one had given them any instructions on ADL care, although bathing and transferring an ill or disabled person requires special skills and can be risky for both the caregiver and care recipient. Almost half reported no training in bandages or wound care, and 10% reported no instruction on managing medications. It is striking that even where instruction was provided, it was by “other,” meaning friends, neighbors, and other informal sources, not the health providers in charge of the care recipient’s care (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Sources of care information from the NAC/AARP study.

Both surveys used the level of intensity scale developed by the NAC for its 1997 survey.12 This measure designates a level of care from 1 (least intensive) to 5 (most intensive), on the basis of a combination of hours of care and numbers of ADLs and instrumental activities of daily living performed. Just under a third (29.5% and 28.9%) were at level 1; another quarter (27.8% and 23.4%) were at the levels 4 and 5, the latter equivalent to nursing home care. The majority were at levels 2 and 3, providing moderately intensive levels of care.

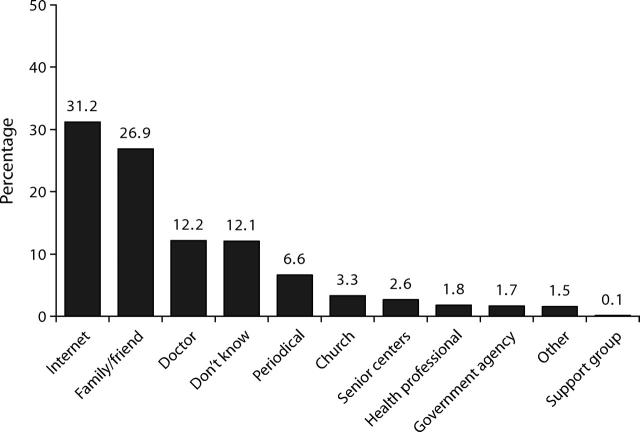

The NAC/AARP survey asked several questions about obtaining information. Almost a third (31.2%) of the young adults reported that the internet was an important source of information, with family and friends second (26.9%). Only 12.2% reported that a doctor provided information, 1.8% another health professional, and 1.7% a government agency (Figure 2 ▶).

FIGURE 2—

Help with instructions from the Harvard/UHF/VNS study.

Despite their considerable time and effort, substantial proportions of young adult caregivers in the NAC/AARP study reported, on a scale of 1 to 5, that they did not experience significant financial hardship (62.7%), physical strain (42.7%), or emotional stress (31.3%). Most of the other responses were clustered around the second and third levels, whereas small but notable percentages reported the highest level of strain, with emotional stress (13.3%) the most common. When asked about specific impacts, however, more than a third (36.4%) reported that they had less time for family and friends, and 43.1% gave up hobbies and social activities because of caregiving.

Like their older counterparts, young adults have a variety of coping strategies, as reported in the NAC/AARP study, including prayer (57.4%), talking to family and friends (54.1%), and using the internet (34.5%). About 40% exercise, and only 2.8% reported taking medication; 13.2% sought professional or spiritual counseling. Although prayer is the most common coping strategy, only 3.3% reported that they found their church to be a source of caregiving information.

Young adult caregivers identified a number of unmet needs. In the Harvard/UHF/VNS survey, 16.8% said that they had difficulty obtaining medical help for the care recipient, whereas 72.1% said that they had difficulty obtaining nonmedical help, defined as home care aides or other assistance; 11.1% reported problems in both areas.

The NAC/AARP respondents had a wider range of options to report: 31.5% reported they needed help or information about keeping the care recipient safe, and 15.1% were concerned about managing behavior, both suggestive of difficulties with dementia patients. Almost equal percentages (17.6% and 15.9%, respectively) needed help with talking to physicians and making end-of-life decisions. About a third (31.4%) wanted more time for themselves, and 22.9% needed help in managing stress.

DISCUSSION

This analysis of two surveys broadens our understanding of the spectrum of family caregivers by demonstrating that a substantial proportion are between the ages of 18 and 25 years, not usually considered a target population for caregiver services. Furthermore, many of these caregivers are young men, which refutes the prevalent gender stereotype but also raises serious questions about whether the types of support services that have traditionally targeted older women are appropriate for them.

Clearly, more work is needed to learn more about the needs and concerns of young adult caregivers. Surveys designed for the total adult caregiver population do not capture the particular features of young adulthood that are most significant. Qualitative studies are also needed to understand caregiving as it is occurring, not just in retrospect. Additional research design should include many more pertinent questions about the impact of caregiving on educational plans, employment experiences, social life, and other factors. Caregiving as a young adult may open up career possibilities in the health and social service professions. On the other hand, higher education, which is associated with higher income, may be less accessible to young adult caregivers. Additional studies should also compare young adult caregivers with their noncaregiving peers.

A few services already exist, which may provide some models for others. For example, the Alzheimer’s Association chapters in Delaware Valley County (based in Marlton, NJ ) and New York City conduct support groups for young adults caring for a parent with early onset disease. Other disease organizations may already have or can organize similar efforts. The internet and e-mail offer many possibilities for an age group that has grown up with computers.

More targeted outreach and information are necessary to reach this group. Religious organizations often have special programs for different age groups; if there are not enough young adult caregivers in a single congregation, leaders might collaborate with other groups to create joint programs.

A broad-based effort is also required. A group of representatives of health care, social service, and other organizations concerned with education and employment should be convened to create a research, practice, and policy agenda. Young adult caregivers should be involved at all stages.

The young adults who are caregivers now are, we suggest, only the first wave of the future. With social changes, such as delayed childbearing and smaller families, aging parents will have to look to children still in their formative years for help. The 2.4 million grandparents raising 1 or more grandchildren now will need help when these youngsters are in their 20s. We speculate that, in the future, care recipients will be even older than they are now, and caregivers will be even younger. What this may mean for a youth-oriented but aging society is an open question.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the assistance of Ewa Wojas, who provided help with the data extraction. We also thank Craig Hill for guidance on the survey methodology.

Human Participant Protection This article is on the basis of national randomized telephone surveys that did not obtain identifiable information and did not require Institutional Review Board approval.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors C. Levine and D. Gould originated the study and supervised all aspects of its implementation. D. Halper and G. G. Hunt assisted with the study and analysis. A. Hart synthesized the analyses. J. Lautz assisted with data retrieval. All authors reviewed drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Becker S. Carers. Research Matters. Children and Young People [special issue]. Sutton, UK: Community Care Magazine; 2004:5–10.

- 2.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shifren K. Early caregiving and adult depression: good news for young caregivers. Gerontologist. 2001; 41:188–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shifren K, Kachorek LV. Does early cargiving matter? The effects on young caregivers’ adult mental health. Int J Behav Dev. 2003;27:338–346. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellmann-Jenkins M, Blankemeyer M, Pinkard O. Young adult children and grandchildren in primary caregiver roles to older relatives and their service needs. Family Relations. 2000;49:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donelan K, Hill CA, Hoffman C, et al. Challenged to care: Informal caregivers in a changing health system. Health Affairs. 2002;21:222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Alliance for Caregiving/AARP. Caregiving in the US. Available at: http://www.caregiving.org. Accessed August 19, 2005.

- 8.Burton WN, Chen C-Y, Conti DJ, Pransky G, Edington DW. Caregiving for ill dependents and its association with employee health risks and productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;10:1048–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Census Bureau. Archives. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/index.html. Accessed September 6, 2005.

- 10.National Alliance for Caregiving and United Hospital Fund. Young Caregivers in the US. September 2005. Available at: http://www.uhfnyc.org. Accessed September 16, 2005.

- 11.Siskowski CT. From Their Eyes . . . Family Health Situations Influence Students’ Learning and Lives in Palm Beach County, Grades 6–12. West Palm Beach, Florida. Available at: http://www.boca-respite.org/children.doc. Accessed August 19, 2005.

- 12.National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. Family Caregiving in the US: Findings from a National Survey, 1997.