Abstract

The involucrin gene encodes a protein of terminally differentiated keratinocytes. Its segment of repeats, which represents up to 80% of the coding region, is highly polymorphic in mouse strains derived from wild progenitors. Polymorphism includes nucleotide substitutions, but is most strikingly due to the recent addition of a variable number of repeats at a precise location within the segment of repeats. Each mouse taxon examined showed consistent and distinctive patterns of evolution of its variable region: very rapid changes in most M. m. domesticus alleles, slow changes in M. m. musculus, and complete arrest in M. spretus. We conclude that changes in the variable region are controlled by the genetic background. One of the M. m. domesticus alleles (DIK-L), which is of M. m. musculus origin, has undergone a recent repeat duplication typical of M. m. domesticus. This suggests that the genetic background controls repeat duplications through trans-acting factors. Because the repeat pattern differs in closely related murine taxa, involucrin reveals with greater sensitivity than random nucleotide substitutions the evolutionary relations of the mouse and probably of all murids.

INVOLUCRIN is a specific protein of terminally differentiated keratinocytes; it is a substrate of the keratinocyte transglutaminase and a precursor of the crosslinked envelope (Rice and Green 1979). In all mammalian involucrin genes examined, about two-thirds of the coding region is composed of a segment of short tandem repeats, but the segment of repeats of anthropoid primates differs from that of nonanthropoid mammals. In the transition from nonanthropoid to anthropoid primates, the segment of repeats of nonanthropoid mammals was deleted and replaced by a new segment of repeats, located downstream in the coding region (Tseng and Green 1988; Green and Djian 1992). Only the tarsioids possess repeats at both locations (Djian and Green 1991). The anthropoid segment of repeats was progressively expanded during subsequent anthropoid evolution by addition of repeats, always close to the 5′-end of the segment, which therefore expanded in a 3′-to-5′ direction (Djian and Green 1989). Because repeat addition continues in present-day humans, involucrin is polymorphic with respect to size in the human population. However, because the differences in size are small, polymorphism cannot be detected by electrophoretic analysis of the protein, but only by restriction fragment analysis of the genes (Simon et al. 1991; Urquhart and Gill 1993; Djian et al. 1995).

The involucrin gene has been sequenced in a large number of nonanthropoid mammals, including the mouse and the rat (Tseng and Green 1988, 1990; Phillips et al. 1990, 1997; Djian and Green 1991; Djian et al. 1993). In contrast to the anthropoid segment of repeats, that of nonanthropoid mammals generally revealed little polymorphism due to recent additions of repeats (Tseng and Green 1988; Phillips et al. 1997). However, sequencing of involucrin alleles of random-bred Swiss mice revealed the existence of extensive size polymorphism, due to differences in the number of repeats in different alleles. Remarkably, these differences resulted from addition of repeats targeted to only one of two classes of alleles. The absence of recombination between any of the alleles examined supported the operation of an intra-allelic mechanism of repeat addition (Delhomme and Djian 2000).

We have now sequenced involucrin alleles of mouse strains derived from wild progenitors. The involucrins of these mice are highly polymorphic with respect to size. As the nature of polymorphic alleles is different in different mouse taxa, we postulate that the process of repeat addition is controlled by the genetic background. We present evidence in favor of the operation of trans-acting factors in the control of the process of repeat addition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Southern blots:

We examined the segments of repeats of 16 strains, each descended from different wild progenitors (Table 1). Inbred strains were provided by the Unité de Génétique des Mammifères (Institut Pasteur, Paris) and random-bred strains by the Conservatoire de la Souris Sauvage (CNRS-Université de Montpellier II). A description of the mouse strains used in this study and a list of bibliographical references can be found at http://www.univ-montp2.fr/~genetix/souris.htm and http://www.cnrs-orleans.fr/~webcdta/ListeSouris.html. Genomic DNA was prepared from liver with a genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and digested with AvaII, which cuts on both sides of the segment of repeats (see Delhomme and Djian 2000, Figure 4). Digested DNA (10 μg) was then submitted to electrophoresis through a 1% agarose gel, transferred to charged nylon, and hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe consisting of most of the mouse involucrin segment of repeats. The resolution of the agarose gel allowed us to determine the number of repeats in the AvaII fragment and to identify mice that were heterozygous for the size of this fragment.

TABLE 1.

Wild-derived mice examined for involucrin

| Taxon | Strain | Origin | Breeding | No. alleles sequenced |

No. of repeats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. m. domesticus | DEB | Spain (Barcelona) | Random | 1 | 29 |

| DIK | Israel (Keshet) | Random | 2 | 31/33 | |

| 22MO | Tunisia (Monastir) | Random | 1 | 41 | |

| WLA | France (Toulouse) | Inbred | 1 | 20 | |

| WMP | Tunisia (Monastir) | Inbred | 1 | 28 | |

| M. m. musculus | DHA | India (Delhi) | Random | 2 | 29/29a |

| MAI | Austria (Illmitz) | Inbred | 1 | 30 | |

| MAM | Armenia (Megri) | Random | 2 | 28/28b | |

| MBT | Bulgaria (Gal Toshevo) | Inbred | 1 | 30 | |

| MPR | Pakistan (Rawalpindi) | Random | 2 | 28/30 | |

| PWK | Czech Republic (Prague) | Inbred | 1 | 19 | |

| TEH | Iran (Teheran) | Random | 1 | 30 | |

| M. m. castaneus | CTP | Thailand (Pathumthani) | Random | 2 | 29/31 |

| M. spretus | SEB | Spain (Barcelona) | Random | 1 | 28 |

| SEG | Spain (Granada) | Inbred | 1 | 28 | |

| STF | Tunisia (Fonduk Djedid) | Inbred | 1 | 28 |

PCR:

Genomic DNA (250 ng) was used for amplification by PCR. The sequence of the upstream primer, starting at codon 64, was 5′-T GTG AAG GAT CTG CCT GAT and that of the downstream primer corresponding to codons 16–9 after the segment of repeats was 5′-G GCT TTT TGG TCC TTG ATA A (Djian et al. 1993; Delhomme and Djian 2000). The PCR product was the result of 30 cycles of amplification (95° for 1 min, 55° for 1 min, and 72° for 2 min) in the presence of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using a PE480 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT). PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) by A/T cloning (Kovalic et al. 1991). For each amplified fragment, a group of six plasmid clones was prepared, and each clone was digested with PstI, which excises a fragment containing the segment of repeats, thus allowing the identification of the clones corresponding to each allele in heterozygous mice.

Nucleotide sequencing:

Nested deletions were generated by progressively digesting each cloned PCR fragment with exonuclease III (Erase a Base System, Promega). Cycle sequencing was performed on a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR system 2400 in the presence of fluorescent dideoxynucleotides. Thermocycling conditions were 30 cycles at 96° for 30 sec, 50° for 15 sec, and 60° for 4 min. Electrophoresis and detection of fluorescent peaks were carried out on an automatic sequencer (ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer). The sequence was determined using the SeqEd v1.0.3 software. Several clones were sequenced for each allele. Sizes deduced from sequencing always corresponded to those determined by agarose gel electrophoresis. The alignment of repeats and the phylogenetic analysis were performed by eye.

RESULTS

The segment of repeats of mouse involucrin alleles:

The coding region of the mouse involucrin gene contains a segment of repeats, which begins with codon 82 and is followed by 73 codons, not including the stop codon (Djian et al. 1993). The segment of repeats was sequenced in 21 alleles found in 16 mouse strains derived from wild progenitors belonging to the taxa Mus musculus domesticus, M. m. musculus, M. m. castaneus, and M. spretus (Table 1). These sequences were compared to those of the six laboratory mouse alleles, which had been previously examined (Delhomme and Djian 2000). As in the Swiss mice, polymorphism due to a variable number of repeats was largely confined to a single location between repeats M and N of the segment of repeats, which could therefore be divided into 5′ constant, variable, and 3′ constant regions (Figure 1). Figure 2 is a summary of the alignment of the repeats of all murine involucrin alleles.

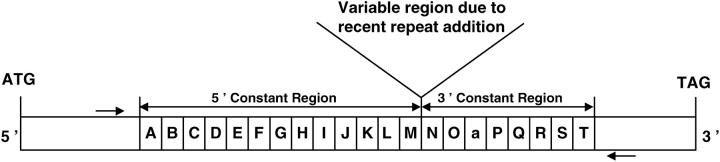

Figure 1.—

Coding region of the mouse involucrin gene. Two-thirds to four-fifths of the coding region is composed of a segment of 19–41 repeats of 13–16 codons. This segment consists of 5′ and 3′ constant regions shared by all mouse alleles and the rat and a variable region, which differs in the various mouse alleles. Repeats shared by the mouse and the rat are indicated by uppercase letters. One repeat, shared by all mouse alleles but not found in the rat, is designated “a” (Delhomme and Djian 2000). Arrows represent primers used in the PCR amplification of the segment of repeats.

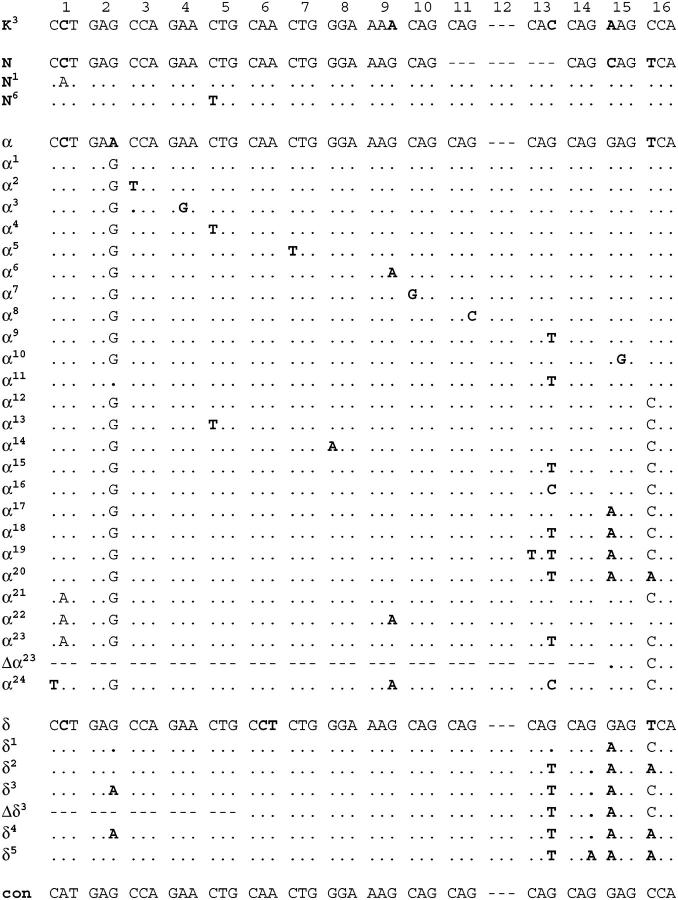

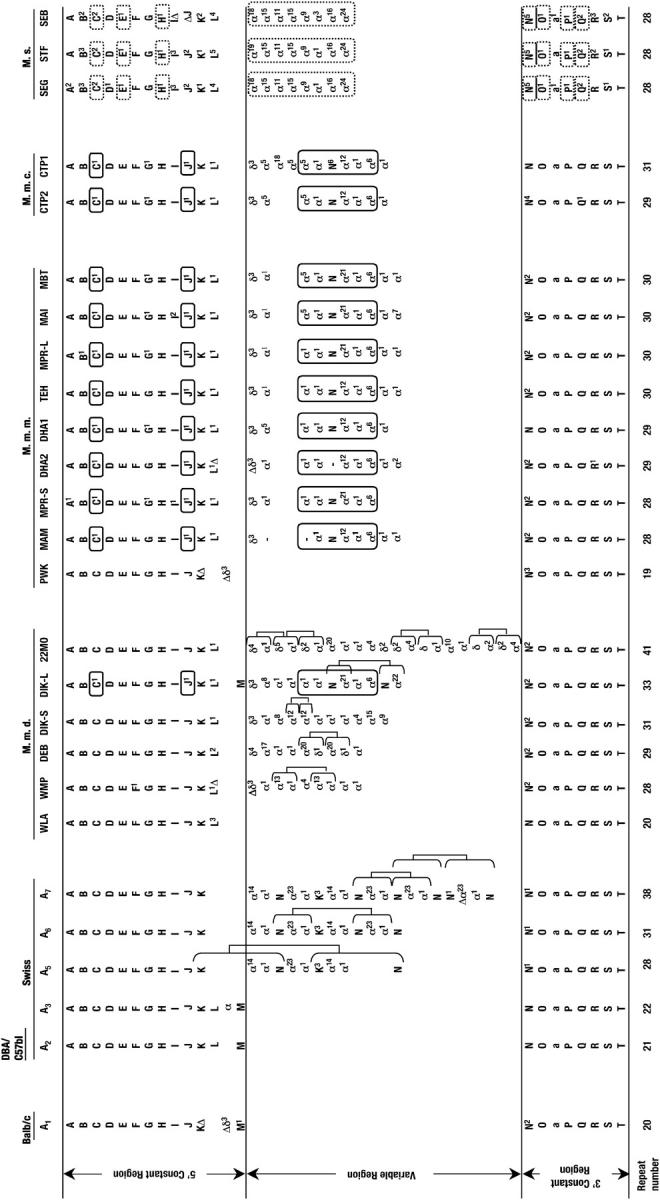

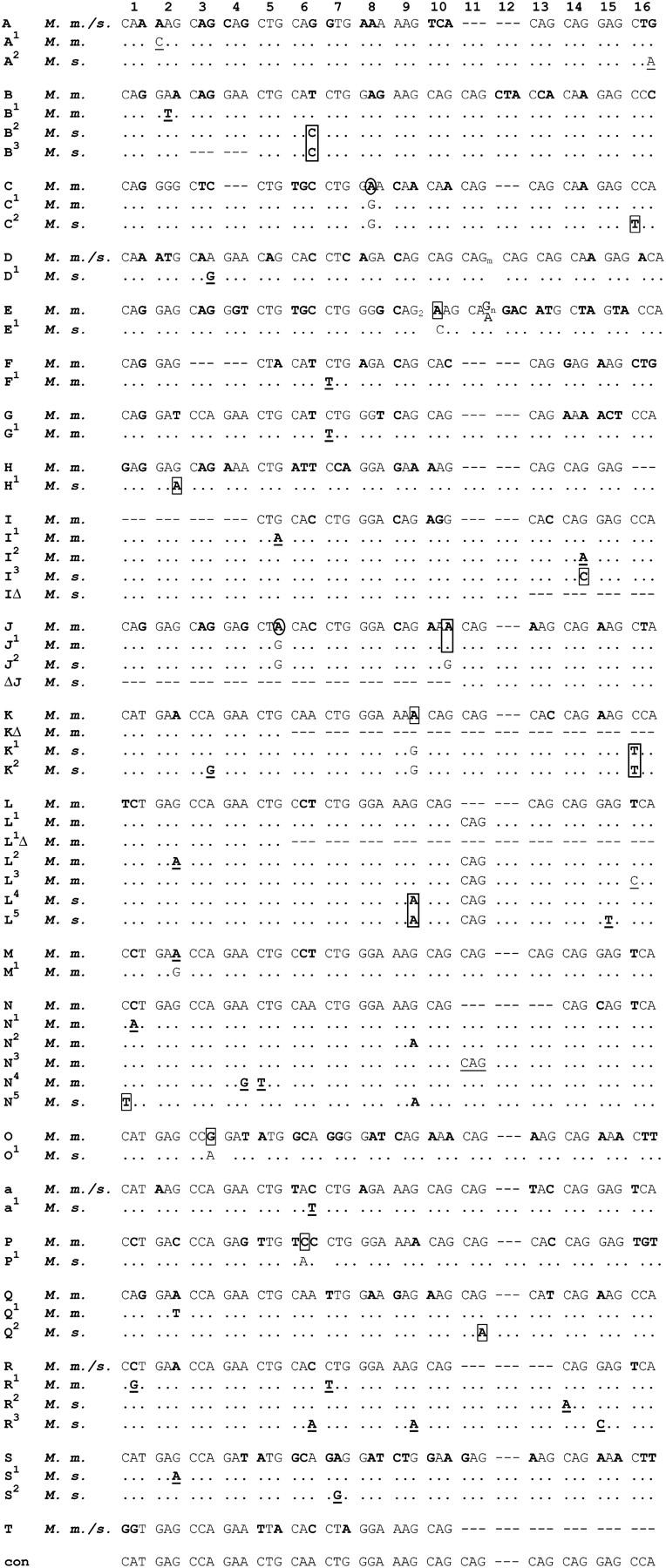

Figure 2.—

Summary of alignment of repeats of mouse involucrin alleles. The segment of repeats is preceded by 81 nonrepeated codons and is followed by 73 nonrepeated codons. Repeats in the constant region are designated by uppercase letters as in Figure 1. Uppercase letters with a superscript indicate variant repeats found in only some alleles; their sequences are shown in Figure 3. Variant repeats specific to M. m. musculus and M. spretus are surrounded by solid-line and dotted-line frames, respectively. Recently added repeats are located in the variable region within two horizontal thin lines. These recent repeats are mostly of α and δ type. The numerous variant α- and δ-repeats are also marked by a superscript and their nucleotide sequences are shown in Figure 4. Some of the duplications that generated repeats of the variable region in the Swiss and M. m. domesticus mice could be traced. An ααNααα block typical of the M. m. musculus alleles is surrounded by a solid-line frame. The ααNααα block is also found in the DIK-L allele of M. m. domesticus. A block of eight α-repeats specific to M. spretus is surrounded by a dotted-line frame. The total number of repeats is given for each allele. KΔ/Δδ3 in A1 and PWK and L1Δ/Δδ3 in WMP and DHA2 were counted as a single repeat.

Nucleotide polymorphism in the constant region:

The constant region contains 21 repeats, 20 of which are shared by nearly all the mouse alleles examined and by the rat. Repeats of the constant region can be aligned in the murids because they contain large numbers of distinguishing marker nucleotides (Djian et al. 1993). Occasional nucleotide substitutions or codon insertions/deletions were present in the repeats of some alleles but not others. These mutations generated variant repeats that differed at one or several positions from the canonical sequences defined earlier for each repeat of the A2 allele (Djian et al. 1993; Delhomme and Djian 2000). The sequences of all canonical and variant repeats are shown in Figure 3. A total of 44 variant repeats were found. Since there are 21 canonical repeats, an average of about two repeats bear nucleotide substitutions for each repeat. Excluding repeat M, which is present in only a few alleles, the frequency of variant repeats tended to increase for repeats bordering on the variable region: seven L repeats and six N repeats bear nucleotide substitutions or deletions/insertions (Figures 2 and 3). The increased frequency of mutations in the repeats located in the vicinity of the variable region must be related to the frequent repeat additions that occur in the variable region.

Figure 3.—

The nucleotide sequence of the repeats of the constant region. Repeats are designated by letters, as in Figure 1. The mouse species in which each repeat is found is shown (M. m., M. musculus; M. s., M. spretus; M. m./s., both M. musculus and M. spretus). For each repeat, the canonical sequence defined earlier in the A2 allele is shown in full (Djian et al. 1993); variant repeats differing from the canonical sequence are indicated with a superscript and only their divergent nucleotides are written. Marker nucleotides differing from the murid consensus (con) are in boldface type. Marker nucleotides shared by all M. m. alleles alone or by all M. s. alleles alone are boxed. Two marker nucleotides that distinguish the C and J repeats typical of M. m. domesticus from the C1 and J1 repeats typical of M. m. musculus are circled. Unshared marker nucleotides are underlined; as shown in Figure 2, the corresponding variant repeats are found in some strains, but not in others.

Repeat addition in the variable region:

All repeats of the variable region of wild-derived mice could be divided into four types: K, N, α, and δ (Figure 4). The origin of repeats α and δ could not be traced since they were not obvious duplicates of more ancient repeats. In the variable region, individual repeats of different strains of mice could be identified by their repeat types and by their marker nucleotides (those that diverge from their repeat consensus); this makes it possible to establish whether repeats of two alleles were added in a common ancestor or were added independently. One K repeat, three N repeats, 26 α-repeats, and seven δ-repeats were found in the 22 alleles examined (Figure 4).

Figure 4.—

The nucleotide sequence of repeats of the variable region. Repeats of the variable region can be divided into four types: K, N, α and δ. Repeats K and N are also found in the constant region, whereas α and δ are virtually specific to the variable region. All α-repeats possess a CAA codon at position 6, while δ-repeats possess CCT at the same position. Variant α- and δ-repeats are indicated by a superscript and only their specific nucleotides are written. Nucleotides differing from the murid consensus are in boldface type. We had previously designated the repeats that compose the variable region of the expanding alleles of Swiss mice as K′, L2, M2, N, β and γ (Delhomme and Djian 2000). In view of the nomenclature adopted for the repeats of wild-derived mice, and of the clear similarity of these repeats with those of Swiss mice, we changed the designation of the repeats of the variable region of Swiss mice: K′, L2, and β became K3, α14, and α23, respectively, while M2 and γ both became α1.

M. m. domesticus:

Five mice, each belonging to a different strain, were examined; a total of six M. m. domesticus alleles were sequenced because the DIK mouse was heterozygous with respect to repeat number. These alleles were highly polymorphic in size. The smallest allele (WLA) contained 20 repeats and no variable region, whereas the largest allele (22MO) contained 41 repeats, of which 21 belonged to the variable region. The repeat number has more than doubled between WLA and 22MO, and the size of the protein has increased from 450 to 765 residues.

Some of the duplications could be traced because duplicated repeats shared specific marker nucleotides. In wild-derived M. m. domesticus, duplications were always of either a single repeat or at most a pair of repeats, never of blocks of 3–4 repeats, as in Swiss mice. Duplications have largely occurred independently in the various strains. For instance, the pattern α13α1 is specific to WMP and must therefore have been generated in WMP after its separation from the other M. m. domesticus strains; α13α1 was then duplicated in the lineage leading to WMP. The same applies to the duplication of α20δ1 in DEB, of α12 in DIK-S, and of δ2α4 in 22MO (Figure 2).

Although duplicated repeats (paralogs) were sometimes identical, they often showed some level of divergence. The expansion of the 22MO allele largely resulted from repeated duplications of a 2-repeat block composed of a type-δ and a type-α repeat. Of the seven δα blocks present in the variable region of 22MO, six are divergent (δ4α1, δ5α1, δ2α1, δ2α4, δα1, and δα2). The variable region of DIK-S was almost entirely formed by repeated duplications of single type-α repeats. Of these 10 repeats, 6 have diverged (α1, α8, α12, α4, α15, and α9). There is not a single nucleotide divergence between the 20 orthologous repeats (A–L, N–T, and a) of DIK-S and 22MO. Therefore these alleles must have diverged recently. Yet, there are numerous divergences between the even more recently generated paralogous repeats of each of the variable regions of the two alleles. This shows that an unusually high frequency of nucleotide substitutions is associated with repeat duplications.

DIK-L stands out among the M. m. domesticus alleles because its 5′ constant region contains a C1 and a J1 repeat typical of M. m. musculus alleles, instead of the C and J repeats typical of M. m. domesticus alleles, and because its variable region contains the pattern α1α1 Nα21α1α6, which is typical of the M. m. musculus alleles (see below). We may conclude that DIK-L is of M. m. musculus origin and was introduced in the M. m. domesticus population by late admixture. The DIK-L allele has then undergone a duplication of a block of two repeats (Nα21 → Nα22). Duplications of two-repeat blocks are frequent in M. m. domesticus, but are never observed in M. m. musculus. Duplications of N repeats are frequent in expanding alleles of Swiss mice (Figure 2), which are also of M. m. domesticus origin (see below). Therefore the most recent duplication in the DIK-L allele is characteristic of M. m. domesticus.

M. m. musculus:

Alleles MAM, MPR-S, DHA2, DHA1, TEH, MPR-L, MAI, and MBT are closely related and represent the typical M. m. musculus alleles. These alleles share a number of distinguishing features: little size polymorphism with a total number of repeats between 28 and 30 and the presence of variant C1 and J1 repeats in the 5′ constant region and of a block of six repeats with the pattern ααNααα in the variable region. The first repeat of the ααNααα block is generally α1 but sometimes α5, the fourth repeat either α12 or α21, the last repeat always α6, and all other repeats, α1. Variability results from the presence of 0–1α repeats immediately upstream and 0–2α repeats immediately downstream of the ααNααα block. Two groups can be distinguished among the M. m. musculus alleles according to whether the fourth repeat of their ααNααα blocks is α12 (MAM, DHA2, DHA1, and TEH) or α21 (MPR-L, MPR-S, MAI, and MBT). MAI and MBT are closely related since they uniquely share a distinctive α5 repeat at the beginning of their ααNααα blocks.

PWK is the shortest involucrin allele so far identified with only 19 repeats and no variable region. Its 5′ constant region contains a C and a J repeat instead of the C1 and J1 repeats typical of the M. m. musculus alleles. PWK is likely to be of M. m. domesticus origin.

M. m. castaneus:

Two alleles of the CTP strain of M. m. castaneus were sequenced. CTP2 and CTP1 contain 29 and 31 repeats, respectively. The two M. m. castaneus alleles are obviously of M. m. musculus type: their 5′ constant region contains C1 and J1 repeats and their variable region possesses an ααNααα block (α5α1Nα12 α1α6). The two CTP alleles appear to be more closely related to DHA1 than to the other M. m. musculus alleles. CTP2 is identical to DHA1, except for the presence of an α5-repeat in its ααNααα block, instead of α1, and for a substitution in the N repeat of the 3′ constant region.

M. spretus:

The nucleotide sequence of three M. spretus alleles (SEG, STF, and SEB), each derived from a different strain, was determined. There was extensive repeat sharing among the constant regions of the M. spretus alleles: seven shared variant repeats were specific to M. spretus (Figure 2). Extensive sharing of variant repeats shows that the common lineages leading to M. spretus and to M. musculus have extensively diverged. The split between these two lineages must therefore be relatively ancient. Each M. spretus strain also contained a relatively large number of unshared variant repeats. For instance, SEB possessed five unshared variant repeats: B2, IΔ/ΔJ, K2, R3, and S2 (Figure 2). We conclude that the lineage leading to SEB has been separated from the other M. spretus lineages for a period of time sufficient to generate five variant repeats.

In contrast to the constant region, the variable region of M. spretus, which is composed of eight α-repeats, showed only two nucleotide substitutions in the three alleles examined (Figure 2). M. spretus is therefore in the paradoxical situation of possessing a variable region that is virtually constant and a constant region that shows some level of variability.

Laboratory mice:

We had previously reported the sequences of six alleles found in four strains of laboratory mice, three of which were inbred (BALB/c, C57bl, and DBA) and one of which was random bred (Swiss). These alleles were divided into nonexpanding (A1–A3) and expanding (A5–A7) alleles. A1 was found in BALB/c only; A2 in C57bl, DBA, and Swiss; and A3 and A5–A7 in random-bred Swiss only. A2 and A3 were closely related; A5–A7 were also closely related, but distinct from either A1 or A2–A3 (see Delhomme and Djian 2000, Figure 8).

None of the alleles of the laboratory mice examined were found in mice derived from wild progenitors. A1 is related to the M. m. musculus PWK allele, with which it uniquely shares a KΔ/Δδ3 repeat at the 3′-end of the constant region. However, A1 possesses an M repeat that is lacking in PWK. A2 and A3 appear to be related to the M. m. domesticus WLA allele, but both possess an M repeat, which is absent from WLA. The 5′ constant region of laboratory alleles resembles that of M. m. domesticus since they all share a C and a J repeat typical of M. m. domesticus. The variable region of A5–A7 resembles that of M. m. domesticus in that it has undergone recent expansion. Expansion of A5–A7 has resulted from duplications of blocks of 3–4 repeats, some of which include a K repeat, whereas the variable regions of the M. m. domesticus alleles were generated by duplications of 1–2 repeats and do not contain K repeats.

From comparison of the sequence of the alleles of laboratory mice, we had previously concluded that repeat M was part of the ancestral mouse allele. However, since repeat M is absent from virtually all wild-derived alleles (Figure 2), we no longer believe that it was present in the ancestral mouse allele, which would therefore have been composed of 20 repeats and not 21, as previously postulated (Delhomme and Djian 2000).

Evolution of mouse involucrin alleles:

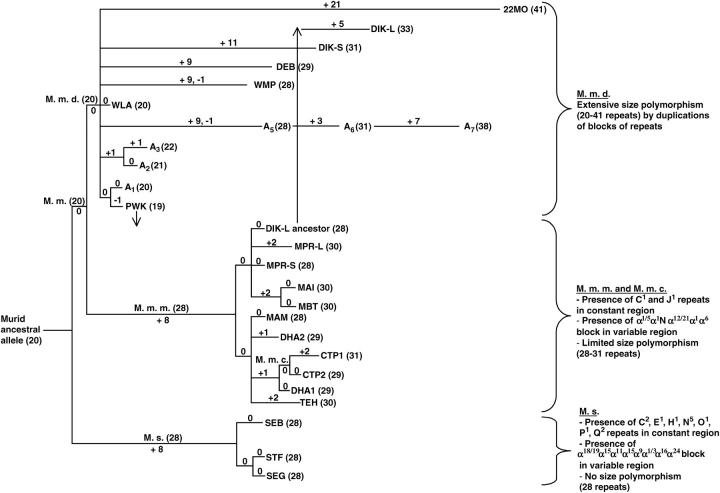

A tree summarizing the origin of the mouse involucrin alleles is shown in Figure 5. The evolutionary tree is based on the repeats of the constant and variable regions. The following evolution can be postulated:

The ancestor of mouse alleles consisted of the 20 repeats of the constant region, which are shared by all murids (A–L, N–T, and a).

The lineage leading to M. spretus diverged from the common lineage leading to M. m. musculus and M. m. domesticus. Such a divergence is supported by the presence of numerous marker nucleotides that coincide in the constant regions of either M. spretus or M. musculus alone (synapomorphies). These shared divergences explain the presence of seven variant repeats typical of the M. spretus constant region (C2, E1, H1, N5, O1, P1, and Q2).

In the common M. spretus lineage, the whole variable region was created by repeated duplications of an α-repeat. These duplications were associated with nucleotide substitutions that diversified the α-repeats of the variable region, of which seven are found in M. spretus alone (α18, α19, α11, α9, α3, α16, and α24; Figure 2).

The three M. spretus strains then diverged from each other, and in all three strains, repeat additions were arrested. Because of this pattern of evolution, there is no size polymorphism of involucrin in M. spretus.

In contrast to M. spretus, the common M. musculus ancestor did not add any repeats before it diverged into M. m. domesticus and M. m. musculus.

Most of the variable region of M. m. musculus, including the ααNααα block framed in Figure 2, was generated in the common M. musculus lineage. Only a few repeats were added or deleted in the M. musculus strains after their divergence from each other. Therefore M. m. musculus shows limited size polymorphism.

In M. m. domesticus, most repeat additions occurred after the divergence of the various lineages from each other, as shown by the presence of specific patterns of duplications in each M. m. domesticus strain. Because of these recent repeat additions, there is extensive size polymorphism in M. m. domesticus.

Figure 5.—

Postulated evolution of the segment of repeats in the involucrin gene of the mouse. The common precursor is likely to have contained 20 repeats of the constant region. A plus sign indicates repeat additions and a minus sign indicates repeat deletions, virtually all of which occurred in the variable region. Numbers in boldface type along the branches of the tree indicate the number of repeats added or deleted to each lineage. Numbers within parentheses show the number of repeats in each allele. Arrows show admixture of the DIK-L ancestor, which is of M. m. musculus origin, into M. m. domesticus and of PWK, which is of M. m. domesticus origin, into M. m. musculus. The points of closer similarity among the three major lineages are summarized. The points of closer similarity among minor lineages can be found in the results.

DISCUSSION

The process of repeat addition is genetically determined by trans-acting factors:

Polymorphism of mouse involucrin has resulted from additions of a varying number of repeats at a specific location between repeats M and N (the variable region). An occasional repeat has been added outside of the variable region, but this was a very rare event and it was always close to the variable region (for instance, repeat α in allele A3 or Δδ3 in A1 and PWK). In the rat, new repeats have also been added between repeats M and N (Djian et al. 1993). The site of new repeat addition is therefore identical in all murids.

Addition of repeats has proceeded differently in each mouse group. This is best illustrated by a comparison of the expanding alleles of M. m. domesticus with the alleles of M. spretus. The constant region of the M. m. domesticus alleles is very homogeneous, presumably because these alleles are of very recent origin. In contrast the variable region is highly polymorphic because it has undergone recent expansion independently in each lineage. Although the M. spretus alleles are of ancient origin, as shown by the numerous divergences of their constant regions, their variable regions are virtually identical. This shows that (1) repeat additions have stopped in the three M. spretus lineages and (2) a mechanism preventing or correcting any nucleotide substitution and specifically targeted to the variable region has operated in M. spretus alone (Figures 2 and 5). These examples show that repeat duplications and nucleotide substitutions in the variable region are controlled by the genetic background in which the involucrin alleles are placed. No such control operates on the constant region.

DIK-L represents a case of admixture of a M. m. musculus allele in M. m. domesticus. When placed in the M. m. domesticus background, DIK-L underwent duplication of a block of two repeats as did other M. m. domesticus alleles, but unlike any M. m. musculus allele (Figure 2). This suggests that when the ancestor of the DIK-L alleles was introduced in the M. m. domesticus subspecies, its process of repeat addition came under the control of trans-acting factors specific to M. m. domesticus.

Nucleotide substitutions and repeat additions:

In M. m. domesticus, the process of repeat addition is associated with a high frequency of nucleotide substitutions. The variable region of 22MO contains 7 δα blocks, which must have been generated by recent duplications of an ancestral δα block. No two of the seven δα blocks are identical. In contrast, no recent nucleotide substitutions are present in the constant region of 22MO, which is identical to that of other M. m. domesticus alleles, such as DIK-S and WLA. The high frequency of substitutions in the variable region explains why it contains so many variant δ and α repeats, whereas so few variant repeats are found in the constant regions of the M. musculus alleles (Figures 3 and 4). This high frequency of nucleotide substitutions further contributes to the rapid divergence of the variable regions.

Repeat addition in the variable region is likely to result from out-of-register pairing between two alleles, which could occur by strand slippage during replication or meiotic recombination. Mispairing could create loops that would be filled in by the DNA polymerases associated with mismatch repair systems, thus leading to repeat additions. If the fidelity of these DNA polymerases were lower than that of the DNA polymerase used in standard DNA replication, a high frequency of substitutions would be associated with repeat additions. A number of low-fidelity polymerases that can synthesize DNA across otherwise replication-blocking DNA structures have been recently described (Ohmori et al. 2001). The operation of such DNA polymerases could explain the high frequency of nucleotide substitutions observed in the variable region of the murine involucrin gene. A high frequency of nucleotide substitutions in microsatellites has also been observed (Djian et al. 1996; Brohede and Ellegren 1999).

From previous analysis of the segment of repeats of the rat and of laboratory mice, there was clear evidence of a process in which a substitution at a nucleotide position in one repeat had spread to the corresponding position in neighboring repeats. This was ascribed to gene conversion since the flanking markers were not recombined. Gene conversion was restricted to the constant region and was suppressed in the variable region of the expanding alleles of laboratory mice (Djian et al. 1993; Delhomme and Djian 2000). A similar suppression is observed in the rapidly expanding variable region of the M. m. domesticus strains derived from wild progenitors. In contrast, the variable region of M. spretus, in which no repeats have been recently added, shows evidence of gene conversion. For instance, a T nucleotide located at position 13 has spread to repeats α18, α15, α11, and α9 (Figures 2 and 4).

The involucrin genes of laboratory mice in relation to M. m. domesticus:

We had previously reported the sequences of DBA, C57bl, BALB/c, and Swiss involucrin alleles (Delhomme and Djian 2000). Comparison of these alleles with those of the strains derived from wild progenitors shows that the involucrin alleles of laboratory mice are closely related to M. m. domesticus alleles. However, none of the alleles of laboratory mice was found among the M. m. domesticus wild alleles. Laboratory mice have been separated from wild mice for <100 years, but during this time laboratory mice have been expanded to a very large population. The expanding alleles of Swiss mice show recent duplications of blocks of repeats (Delhomme and Djian 2000). It is conceivable that rapidly evolving genes, such as the involucrin gene, could have undergone appreciable evolutionary changes in the laboratory mice. Sequencing of the involucrin gene from frozen samples of early Swiss mice, if such samples were available, would permit us to determine whether this is the case.

DBA, C57bl, and random-bred Swiss share the A2 allele (Figure 2). These three mouse strains have independent origins: DBA in 1909 from W. E. Castle at Harvard, C57bl in 1921 from a dealer in Massachusetts, and Swiss before 1920 from the Institut Pasteur in Paris (Lynch 1969; Nishioka 1995). The A2 allele was not found in the strains derived from wild mice that we examined and must therefore be infrequent in wild mice. Either the A2 allele was frequent in some fancy mice that pet dealers exchanged and from which the laboratory strains were all derived or some mixing of the three laboratory strains occurred early in their history.

Utility of the involucrin gene as a phylogenetic marker of the mouse:

The genus Mus is composed of ∼40 species. Considerable effort has been devoted to establishing the phylogeny of this genus, because a number of mouse species are used in comparative studies. Comparisons of homologous nucleotide sequences require large data sets and have often yielded conflicting phylogenetic trees, particularly for closely related mouse subspecies. This is because nucleotide substitutions occur rather infrequently and are mostly random. The rapid addition of repeats in some mouse subspecies and the genetic control of the additions render the involucrin gene a very sensitive phylogenetic marker. For instance, it is immediately obvious from examination of the variable regions of the M. musculus mice in Figure 2 that M. m. castaneus is more closely related to M. m. musculus than to M. m. domesticus. Lundrigan et al. (2002) reached a similar conclusion after studying the complete sequences of six genes; five of the six genes yielded a trichotomy for these three mouse subspecies. Other studies based on RFLPs and mitochondrial DNA sequences have alternatively placed M. m. castaneus as a sister group of M. m. domesticus (Santos et al. 1993; Suzuki and Kurihara 1994) or M. m. musculus (Tucker et al. 1989; Prager et al. 1996).

The origins and dispersals of Pacific peoples have been studied recently using the mitochondrial DNA phylogenies of the Pacific rat, a commensal of humans (Matisoo-Smith and Robins 2004). Although polymorphism of rat involucrin has never been demonstrated, we suspect that such polymorphism exists, since a group of closely related repeats is found between repeats M and N of the single rat involucrin allele sequenced (Djian et al. 1993). Since closely related repeats are likely to be of recent origin, their presence suggests that the process of repeat addition might be active in present-day rats. Rat involucrin could then be useful in studies such as that of Matisoo-Smith and Robins (2004). Since M. musculus is also a commensal species, whose spread is thought to have been largely human mediated (Gündüz et al. 2000), polymorphism of M. musculus involucrin could provide information on the history of colonization by humans. Involucrin should be a useful nuclear marker for phylogenetic studies in which mitochondrial DNA variations are currently used.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jean-Louis Guénet and Isabelle Lanctin (Unité de Génétique des Mammifères, Institut Pasteur) for providing specimens of inbred strains derived from wild mice. We thank François Bonhomme and Annie Orth [Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Université de Montpellier] for random-bred strains. These investigations were aided by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession nos. AY898707, AY898708, AY898709, AY898710, AY898711, AY898712, AY898713, AY898714, AY898715, AY898716, AY898717, AY898718, AY898719, AY898720, AY898721, AY898722, AY898723, AY898724, AY898725, AY898726.

References

- Brohede, J., and H. Ellegren, 1999. Microsatellite evolution: polarity of substitutions within repeats and neutrality of flanking sequences. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 266: 825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhomme, B., and P. Djian, 2000. Expansion of mouse involucrin by intra-allelic repeat addition. Gene 252: 195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djian, P., and H. Green, 1989. Vectorial expansion of the involucrin gene and the relatedness of the hominoids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86: 8447–8451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djian, P., and H. Green, 1991. Involucrin gene of tarsioids and other primates: alternatives in evolution of the segment of repeats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 5321–5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djian, P., M. Phillips, K. Easley, E. Huang, M. Simon et al., 1993. The involucrin genes of the mouse and the rat: study of their shared repeats. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10: 1136–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djian, P., B. Delhomme and H. Green, 1995. Origin of the polymorphism of the involucrin gene in Asians. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 56: 1367–1372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djian, P., J. M. Hancock and H. S. Chana, 1996. Codon repeats in genes associated with human disease: fewer repeats in the genes of nonhuman primates and nucleotide substitutions concentrated at the site of reiteration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 417–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, H., and P. Djian, 1992. Consecutive actions of different gene-altering mechanisms in the evolution of involucrin. Mol. Biol. Evol. 9: 977–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gündüz, I., C. Tez, V. Malikov, A. Vaziri, A. V. Polyakov et al., 2000. Mitochondrial DNA and chromosomal studies of wild mice (Mus) from Turkey and Iran. Heredity 84: 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalic, D., J.-H. Kwak and B. Weisblum, 1991. General method for direct cloning of DNA fragments generated by the polymerase chain reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 19: 4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundrigan, B. L., S. A. Jansa and P. K. Tucker, 2002. Phylogenetic relationships in the genus Mus, based on paternally, maternally, and biparentally inherited characters. Syst. Biol. 51: 410–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, C. J., 1969. The so-called Swiss mouse. Lab. Anim. Care 19: 214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matisoo-Smith, E., and J. H. Robins, 2004. Origins and dispersals of Pacific peoples: evidence from mtDNA phylogenies of the Pacific rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 9167–9172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka, Y., 1995. The origin of common laboratory mice. Genome 38: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori, H., E. C. Friedberg, R. P. P. Fuchs, M. F. Goodman, F. Hanaoka et al., 2001. The Y family of DNA polymerases. Mol. Cell 8: 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M., P. Djian and H. Green, 1990. The involucrin gene of the Galago: existence of a correction process acting on its segment of repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 265: 7804–7807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M., R. H. Rice, P. Djian and H. Green, 1997. The involucrin gene of the tree shrew: recent repeat additions and the relocation of cysteine codons. Gene 187: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prager, E. M., H. Tichy and R. D. Sage, 1996. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in the eastern house mouse, Mus musculus: comparison with other house mice and report of a 75-bp tandem repeat. Genetics 143: 427–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, R. H., and H. Green, 1979. Presence in human epidermal cells of a soluble protein precursor of the cross-linked envelope: activation of the cross-linking by calcium ions. Cell 18: 681–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J. Y., Y. Cole and A. Pellicer, 1993. Phylogenetic relationships among laboratory and wild-origin Mus musculus strains on the basis of genomic DNA RFLPs. Mamm. Genome 4: 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, M., M. Phillips and H. Green, 1991. Polymorphism due to variable number of repeats in the human involucrin gene. Genomics 9: 576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H., and Y. Kurihara, 1994 Genetic variation of ribosomal RNA in the house mouse, Mus musculus, pp. 107–119 in Genetics in Wild Mice: Its Application to Biomedical Research, edited by K. Moriwaki, T. Shiroishi and H. Yonekawa. Japan Science Society Press, Tokyo.

- Tseng, H., and H. Green, 1988. Remodeling of the involucrin gene during primate evolution. Cell 54: 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, H., and H. Green, 1990. The involucrin genes of pig and dog: comparison of their segments of repeats with those of prosimians and higher primates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 7: 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, P. K., B. K. Lee and E. M. Eicher, 1989. Y chromosome evolution in the subgenus Mus (genus Mus). Genetics 122: 169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, A., and P. Gill, 1993. Tandem-repeat internal mapping (TRIM) of the involucrin gene: repeat number and repeat-pattern polymorphism within a coding region in human populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 53: 279–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]