Abstract

Nitroalkenes are a class of cell signaling mediators generated by NO and fatty acid-dependent redox reactions. Nitrated fatty acids such as 10- and 12-nitro-9,12-octadecadienoic acid (nitrolinoleic acid, LNO2) exhibit pluripotent antiinflammatory cell signaling properties. Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) is up-regulated as an adaptive response to inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress. LNO2 (1–10 μM) induced HO-1 mRNA and protein up to 70- and 15-fold, respectively, in human aortic endothelial cells. This induction of HO-1 occurred within clinical LNO2 concentration ranges, far exceeded responses to equimolar amounts of linoleic acid and oxidized linoleic acid, and rivaled that induced by hemin. Ex vivo incubation of rat aortic segments with 25 μM LNO2 resulted in a 40-fold induction of HO-1 protein that localized to endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Actinomycin D inhibited LNO2 induction of HO-1 in human aortic endothelial cells, and LNO2 activated a 4.5-kb human HO-1 promoter construct, indicating transcriptional regulation of the HO-1 gene. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) receptor antagonist GW9662 did not inhibit LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction, and a methyl ester derivative of LNO2 with diminished PPARγ binding capability also induced HO-1, affirming a PPARγ-independent mechanism. The NO scavengers 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide and oxymyoglobin partially reversed induction of HO-1 by LNO2, revealing that LNO2 regulates HO-1 expression by predominantly NO-independent mechanisms. In summary, the metabolic and inflammatory signaling actions of nitroalkenes can be transduced by robust HO-1 induction.

Keywords: nitrated lipids, reactive nitrogen species, vascular endothelial cells

NO displays diverse cell signaling actions, including modulation of oxidative stress, vascular relaxation, cell proliferation, neurotransmission, and inflammatory cell function (reviewed in ref. 1). Recently, it has been observed that reactions between NO-derived species, unsaturated fatty acids, and lipid oxidation intermediates yield fatty acid oxidation and nitration products (2, 3). Nitroalkene derivatives of all principal unsaturated fatty acids are present in human blood and urine and represent an abundant pool of bioactive oxides of nitrogen, with tissue levels of these species influenced by endogenous redox reactions and dietary intake of nitrated lipids. Nitrolinoleic acid (10- and 12-nitro-9,12-octadecadienoic acid, LNO2) is present in plasma and red blood cell membranes at concentrations of ≈500 nM (3). Nitroalkene fatty acid derivatives induce adaptive antiinflammatory responses by means of induction of cGMP-dependent and cGMP-independent cell signaling reactions that result in inhibition of platelet and neutrophil activation (4, 5), vessel relaxation (6), and activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-dependent gene expression (7).

Vascular tissues maintain viability during inflammation by eliciting adaptive and protective responses. Recent studies have shown that heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) plays a central role in vascular inflammatory signaling reactions and mediates a protective response in several inflammatory diseases, including atherosclerosis, acute renal failure, vascular restenosis, transplant rejection, and sepsis (reviewed in ref. 8). HO-1, a 32-kDa enzyme, is the rate-limiting step in the degradation of heme, yielding biliverdin, carbon monoxide, and iron (9). Biliverdin is subsequently converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase. All heme catabolites can contribute to integrative protective responses to oxidative stress (10). Specifically, HO activity reduces levels of prooxidative heme (11), with the iron released from heme catabolism rendered largely redox-inactive by ferritin sequestration. Ferritin is often coinduced with HO-1 and also displays cytoprotective functions (12). Heme degradation serves as the major endogenous source of carbon monoxide, a gas isoelectronic with NO that displays antiinflammatory, antiapoptotic, vasodilatory, and immune modulatory functions (13–15). The porphyrin metabolites biliverdin and bilirubin also scavenge reactive oxygen species (16, 17). Finally, HO-1 induction is associated with concomitant up-regulation of the cell-cycle regulatory protein p21, which mediates antiapoptotic signaling during oxidative injury (18). Biliverdin, bilirubin, and carbon monoxide, acting individually or in concert, exert protective effects in vitro and in vivo in animal models of inflammatory injury (19).

Because both nitroalkenes and HO-1 are emerging as key mediators of adaptive inflammatory responses, the impact of LNO2 on HO-1 gene expression was examined. Herein, the marked up-regulation of HO-1 gene expression by LNO2 in vascular cells is reported, with this induction occurring primarily at the transcriptional level. We conclude that LNO2 mediates the induction of HO-1 by means of PPARγ-independent and both NO-dependent and NO-independent mechanisms.

Results

LNO2 Induces HO-1 mRNA and Protein in Human Aortic Endothelial Cells (HAEC).

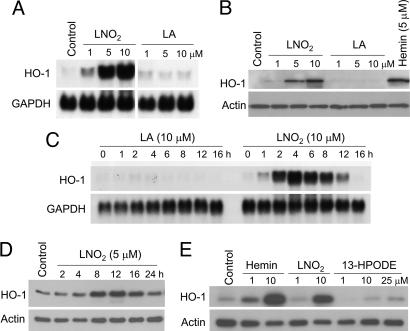

Incubation of HAEC with LNO2 (4 h) induced HO-1 mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A), with ≈8-, 50-, and 70-fold increases over basal HO-1 mRNA expression at 1, 5, and 10 μM LNO2, respectively. Western blot analysis showed that LNO2 induced HO-1 protein expression by 2-, 5-, and 15-fold 16 h after addition of 1, 5, and 10 μM LNO2, respectively (Fig. 1B). Induction of HO-1 was specifically due to the nitroalkene moiety of LNO2, because linoleic acid (LA) did not induce HO-1 expression (Fig. 1 A–C). Maximum induction of HO-1 mRNA occurred at 4 h with 10 μM LNO2, with a corresponding increase in maximal protein expression at 12 h (Fig. 1 C and D).

Fig. 1.

Induction of HO-1 mRNA and protein by LNO2. (A) HAEC were incubated with LNO2 or LA at the indicated concentrations for 4 h, and Northern blot analysis was performed as described in Methods. (B) HAEC were incubated with the indicated concentrations of LNO2, LA, or hemin (positive control) for 16 h. Western blotting was performed as described in Methods. (C) HAEC were incubated with LA or LNO2 for the indicated times, and Northern blot analysis was performed as above. (D) Western blot analysis for HAEC treated with LNO2 for the indicated times. (E) Western blot analysis for HAEC treated as noted for 16 h.

For endothelial cells, 13(S)-hydroperoxy-octadecadienoic acid (13-HPODE) is the most potent HO-1-inducing component of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (20). Cells treated with equimolar amounts of LNO2, hemin, and 13-HPODE revealed that LNO2-dependent HO-1 induction far surpassed that induced by 13-HPODE and rivaled that of hemin (Fig. 1E). Similar extents of HO-1 mRNA expression in response to these mediators also occurred (data not shown). Oxidized lipids, including 13-HPODE, induce HO-1 expression in HAEC by means of iron-dependent, deferoxamine (DFO)-inhibitable mechanisms (21, 22). HAEC pretreated with 5, 50, or 500 μM DFO for 16 h and then exposed to 5 μM LNO2 in the presence of DFO showed no impact of DFO toward LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction (data not shown). Treatment of cells with 1 and 10 μM ebselen, a glutathione peroxidase mimic and lipid peroxide scavenger, or 0.4, 4, and 40 μM butylated hydroxytoluene, an antioxidant, did not attenuate LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction (data not shown).

LNO2-Mediated HO-1 Induction Occurs at the Transcriptional Level and Not by Stabilization of HO-1 mRNA.

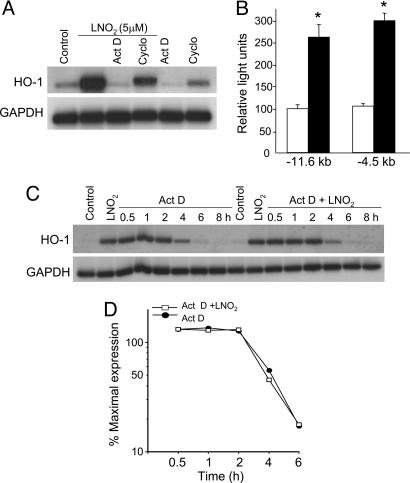

HO-1 expression of HAEC treated with 5 μM LNO2 was examined after a 30-min pretreatment with 4 μM actinomycin D (Act D), a transcriptional inhibitor, or 20 μM cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis. HO-1 mRNA expression was reduced to basal levels after treatment with Act D, supporting that LNO2 transcriptionally regulates HO-1 expression (Fig. 2A). Cycloheximide partially reduced LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction (≈40%), revealing that HO-1 induction by LNO2 depends on both de novo RNA synthesis and new protein synthesis. Transient transfection of −11.6- and −4.5-kb human HO-1 promoter constructs in HAEC showed significant reporter activation with LNO2 treatment, supporting a requirement of specific DNA sequences in the transcriptional regulation of LNO2-mediated HO-1 gene expression (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effect of Act D and cycloheximide (Cyclo) on HO-1 mRNA induction by LNO2. (A) HAEC were incubated for 4 h with the indicated stimuli, and HO-1 and GAPDH mRNA levels were determined by Northern blot analysis. (B) HAEC were transiently transfected with equimolar amounts of pHOGL3/11.6 or pHOGL3/4.5. Cells were exposed to vehicle control (open bars) or 5 μM LNO2 (filled bars) for 16 h, and luciferase assays were performed. Results are derived from five independent experiments (n = 6 per group; ∗, P < 0.001 vs. control). (C and D) LNO2-mediated HO-1 mRNA stability and half-life. HAEC were preincubated with 5 μM LNO2 for 4 h, washed, and exposed to 4 μM Act D in the absence (filled circle) or presence (open square) of additional LNO2. RNA was isolated at the indicated times for Northern blot analysis as described in Methods.

Whereas most stimuli activate HO-1 by transcriptional regulation, some inducers, including NO, also posttranscriptionally increase mRNA stability (23). To evaluate the contribution of message stability in LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction, HAEC were treated with 5 μM LNO2 for 4 h, washed, and treated with 4 μM Act D for 8 h in the presence or absence of additional LNO2 (5 μM). The half-life of HO-1 mRNA was ≈4 h in cells treated with Act D alone or Act D with additional LNO2 (Fig. 2 C and D), indicating that mRNA stability is not involved in LNO2-stimulated HO-1 gene expression.

HO-1 Induction by LNO2 Occurs by NO-Dependent and NO-Independent Mechanisms.

NO induces HO-1 gene expression in a variety of cell types (24–26). Because LNO2 decays to release NO in aqueous milieu (27), the contribution of NO to HO-1 induction was explored. HAEC were pretreated with the NO scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (cPTIO; 8, 80, and 800 μM) for 30 min, followed by treatment with 5 μM LNO2 for 4 h. The NO donor (Z)-1-{N-[3-aminopropyl]-N-[4-(3-aminopropylammonio)butyl]-amino}-diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (SNONOate; 500 μM) was used as a positive control for NO-mediated induction of HO-1. cPTIO (800 μM) completely reversed SNONOate induction of HO-1 mRNA, as expected (Fig. 3A). However, treatment of cells with cPTIO in the presence of LNO2 only partially reversed HO-1 transcript levels when compared with induction of HO-1 by LNO2 alone (Fig. 3 A and B). The effect of another NO scavenger, oxymyoglobin (1, 10, and 100 μM), was also examined. As shown in Fig. 3C, pretreatment with oxymyoglobin at concentrations of 10 and 100 μM induced only a modest (≈25%) decrease in LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction. These results support that LNO2-induced HO-1 expression occurs by both NO-dependent and NO-independent mechanisms. This finding was further corroborated by the effects of SNONOate and LNO2 on promoter constructs transfected into HAEC (Fig. 3D). LNO2 robustly activated a −4.5-kb human HO-1 promoter construct, whereas the NO donor did not significantly activate this construct. These results affirm that LNO2-mediated HO-1 gene expression is predominantly NO-independent.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the NO scavengers cPTIO and oxymyoglobin on HO-1 mRNA induction by LNO2. (A) HAEC were incubated with the indicated stimuli for 4 h, and HO-1 and GAPDH mRNA levels were determined by Northern blot analysis. (B) Dose–response with cPTIO in HAEC stimulated with or without LNO2. (C) Effect of oxymyoglobin on LNO2-mediated HO-1 expression. (D) Differential activation of the −4.5-kb human HO-1 promoter. HAEC were transiently transfected with pHOGL3/4.5 as described in Methods. Cells were exposed to vehicle control, 5 μM hemin, 5 μM LNO2, or 25 μM 13-HPODE for 16 h. Cells were treated with 500 μM SNONOate for 1 h, washed, and incubated in 1% FBS-containing medium for 15 h. Luciferase assays were performed for all conditions. Results are derived from five independent experiments (n = 6 per group; ∗, P < 0.01 vs. control, SNONOate, and 13-HPODE). (E) Effect of LNO2 decay products on HO-1 gene expression. HAEC were treated for 4 h with 5 μM freshly synthesized LNO2 or 5 μM LNO2 decayed for 24 h in 100 mM KPi buffer (pH 7.4) plus 100 μM diethylenetriaminepentaacetate. HO-1 and GAPDH mRNA levels were determined by Northern blot analysis. (F) Mass spectrometric detection of LNO2 decay. LNO2 (3 μM) was incubated in 100 mM KPi, at given time points an aliquot was extracted, and the remaining LNO2 was quantitated by means of LC-mass spectrometry.

LNO2 reacts with water when solvated in neutral aqueous milieu to yield nitrohydroxy derivatives (27). To evaluate whether this or other LNO2 decay products influence HO-1 gene expression, 50 μM LNO2 was first added to 100 mM KPi/100 μM diethylenetriaminepentaacetate (pH 7.4) for 24 h. HAEC were then treated with decay products from 5 μM LNO2 in culture medium for 4 h. HO-1 message in samples treated with decayed LNO2 at 24 h was decreased (≈45%) when compared with cells treated with native LNO2 (Fig. 3E). Mass spectrometric analysis of 24-h-decayed LNO2 confirmed loss of the parent ion with ≈20% of residual LNO2 remaining in the samples (Fig. 3F).

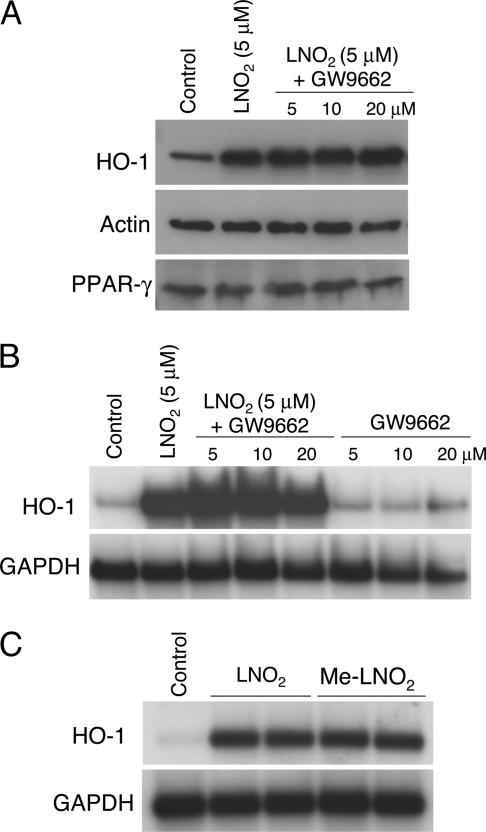

LNO2 Induces HO-1 by PPARγ-Independent Mechanisms.

LNO2 is a potent endogenous ligand for PPARγ and, to a lesser extent, PPARα and PPARδ (7). Previously it was proposed that PPARγ agonists like 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 contribute to induction of HO-1 gene expression (28). To explore whether LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction is PPARγ-dependent, the presence of PPARγ receptors in HAEC was first confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4A), and then HAEC were treated with the PPARγ receptor antagonist GW9662 (5, 10, and 20 μM) and LNO2 (5 μM). GW9662 had no effect on LNO2-mediated HO-1 mRNA and protein expression and, in contrast, modestly enhanced HO-1 mRNA induction (Fig. 4 A and B). A methyl derivative of LNO2 (Me-LNO2), competent to release NO and retaining electrophilic reactivity but lacking a capacity to interact with critical motifs responsible for high-affinity PPARγ ligand binding (unpublished observations), induced HO-1 mRNA expression to a similar degree as LNO2, further supporting that endothelial LNO2-mediated HO-1 gene expression is PPARγ-independent (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Role of PPARγ in LNO2-mediated induction of HO-1. (A) HAEC were treated with the PPARγ antagonist GW9662 for 30 min followed by 5 μM LNO2 for 16 h. HO-1, actin, and PPARγ protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis. (B) HAEC were treated with a PPARγ antagonist GW9662 for 30 min followed by 5 μM LNO2 for 4 h. Control samples were treated with GW9662 for 4 h in the absence of LNO2. HO-1 and GAPDH mRNA levels were determined by Northern blot analysis. (C) HAEC were treated with vehicle control or 5 μM concentrations of native nitroalkene (LNO2) or a nitroalkene methyl ester (Me-LNO2) for 4 h. HO-1 and GAPDH mRNA levels were determined by Northern blot analysis.

LNO2 Induces HO-1 Expression in the Vasculature.

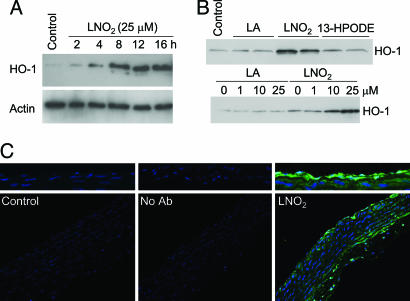

Freshly isolated rat aortic segments incubated with 25 μM LNO2 showed maximal HO-1 protein expression at 12 and 16 h, exceeding levels of HO-1 expression induced by equimolar concentrations of 13-HPODE (Fig. 5A and B). The induction was dose-dependent, and native LA alone did not induce HO-1 (Fig. 5B). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that HO-1 induction was localized to aortic endothelial and smooth muscle cells (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Induction of HO-1 in rat aortic endothelial and smooth muscle cells. (A) Freshly isolated rat aortic segments were treated with vehicle control or LNO2 for 2, 4, 8, 12, or 16 h. (B) Aortic segments were treated with 25 μM LA, LNO2, or 13-HPODE for 16 h (Upper) and 0, 1, 10, and 25 μM LA or LNO2 for 16 h (Lower). Segments were homogenized and assayed for HO-1 or actin by Western blotting as described in Methods. (C) Aortic segments were treated with vehicle control or LNO2 for 16 h, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and mounted to slides. Immunofluorescence detection of HO-1 protein (green) and DAPI nuclear staining was performed on sections with nonimmune rabbit IgG as a negative control (Center). (Upper) Higher magnification of the endothelial layer is shown.

Discussion

There is an expanding appreciation that NO-derived species direct the oxidation, nitrosation, and nitration of diverse biomolecules, yielding products with altered structural and functional properties (29). In the context of cell signaling, NO-derived species regulate protein kinase and phosphatase activities, structural protein function, redox-sensitive transcription factors, mitochondrial respiratory and apoptotic function, and, in general, net cellular redox status (30). Recently we observed that NO-dependent oxidative inflammatory reactions yield fatty acid nitration products that display cell signaling capabilities (2, 4). These fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives, the most clinically abundant bioactive oxides of nitrogen, are unique in that they exhibit pluripotent cell signaling properties (31). These species act in part by serving as hydrophobically regulated NO donors and potent endogenous PPAR ligands (7, 27). The chemical properties of nitroalkenes that facilitate their unique cell signaling actions include (i) the strong electrophilic nature of the β carbon adjacent to the alkenyl nitro bond, (ii) an ability to readily undergo Nef-like acid-base reactions to release NO, (iii) their ability to partition into both hydrophobic and hydrophilic compartments, and (iv) a strong affinity for the PPAR ligand binding pocket.

LNO2 induces HO-1 mRNA and protein in HAEC by means of mechanisms distinct from those of oxidized LA (Fig. 3D). This induction of HO-1 was regulated primarily at the transcriptional level and does not involve mRNA stabilization (Fig. 2). Promoter studies showed that HO-1 induction requires sequences distinct from those required for NO donor- and oxidized lipid-mediated induction (Fig. 3D). LNO2 also induces HO-1 expression in a PPARγ-independent fashion in endothelial cells (Fig. 4). To our knowledge, these data are the first to demonstrate that fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives activate the gene expression of a critical cell inflammatory signaling and oxidative defense enzyme, HO-1.

Proinflammatory stimuli, including oxidized low-density lipoprotein, cytokines, and NO induce HO-1 gene expression (20, 21, 23–26). Of note, the mechanism of HO-1 induction by LNO2 appears to be distinct from these other stimuli and may also account for some component of the HO-1-inducing actions of these stimuli, in as much as these stimuli can include or induce fatty acid nitration products. This finding is corroborated by data showing (i) marked induction of HO-1 by LNO2 to an extent that far exceeds that induced by equimolar concentrations of oxidized lipid derivatives (Fig. 1E), (ii) induction of HO-1 that occurs even in the presence of the NO scavengers cPTIO and oxymyoglobin (Fig. 3A–C), (iii) persistence of HO-1 induction by LNO2 after decay and release of NO by the parent molecule (Fig. 3E), (iv) differential responses of the −4.5-kb human HO-1 promoter to LNO2 compared with 13-HPODE (Fig. 3D), and (v) differential activation of the HO-1 promoter by LNO2 and the NO donor SNONOate (Fig. 3D). These data support that HO-1 induction by LNO2 occurs by predominantly NO-independent mechanisms and support the presence of different transcriptional response elements for nitrated versus oxidized LA. The observation that LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction is only partially NO-dependent is provocative, because the aqueous decay of LNO2 yields NO, an alternative stimulus for HO-1 induction.

Fatty acids such as 13-HPODE, lysophosphatidic acid, and 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 are weak ligands for the nuclear hormone receptor PPARγ that do not act within physiological concentration ranges (7, 32). 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 is reported to induce HO-1 in several cell types by mainly PPARγ-independent mechanisms (28, 33). LNO2 is a robust PPARγ ligand that acts at physiological concentrations and rivals thiazolidinedione PPARγ agonists for potency in activating PPARγ-driven reporter gene expression, macrophage CD-36 expression, adipocyte differentiation, and glucose uptake (7). Herein LNO2 induced full HO-1 expression even in the presence of the PPARγ receptor antagonist GW9662. The non-PPARγ-activating methyl derivative of LNO2 also retains HO-1 inducibility, supporting a PPARγ-independent pathway for LNO2-mediated HO-1 induction in endothelial cells. Furthermore, the −11.6-kb human HO-1 promoter does not contain any consensus PPARγ response elements (AGGTCAnAGGTCA) (search performed using vector nti software, Invitrogen) that would be expected in promoters of PPAR-dependent target genes. Further studies to delineate the specific LNO2-responsive element in the human HO-1 promoter, as well as the upstream signaling pathways that mediate HO-1 gene expression by LNO2, remain of interest.

Activation of HO-1 by LNO2 has relevance to inflammatory injury, specifically with respect to vascular disorders. In this regard, several recent studies have shown that expression of HO-1 beneficially limits atherosclerosis and vascular restenosis (34, 35). Plasma concentrations of free LNO2 in normal healthy humans is ≈500 nM (3), and in this study concentrations of LNO2 as low as 1 μM were associated with HO-1 induction. Increased levels of 18:2 nitration products (nitrolinoleate and cholesteryl nitrolinoleate) are present in plasma from hyperlipidemic patients compared with normolipidemic patients (36, 37). Using stable isotope dilution LC-mass spectrometry, current data indicate significantly increased levels of nitroalkenes in a variety of inflammatory conditions and animal models of inflammation (unpublished observations). This increased extent of fatty acid nitration is not unexpected, because the NO-dependent redox reactions induced by inflammatory stimuli are a byproduct of both the increased expression and uncoupled electron transfer activity of NO synthases and increased rates of production of reactive oxygen species by a variety of cellular oxidases and oxygenases. One consequence of this convergence of reactive species is an increase in rates of formation of various lipid radical intermediates and oxides of nitrogen (e.g., peroxynitrite and nitrogen dioxide) that support nitration of unsaturated fatty acids (2).

In summary, we show that LNO2 is a potent inducer of HO-1 gene expression, a central defensive enzyme in tissue antiinflammatory responses to vascular injury. At present, nitroalkenes are appreciated to mediate multiple adaptive inflammatory signaling actions that influence the differentiated functions of platelets, neutrophils, macrophages, smooth muscle cells, and now endothelium (5–7, 38). Considering the promising vascular protective effects of HO-1 expression, the present observations reveal that induction of HO-1 expression represents a key cell signaling action of inflammatory-derived lipid nitroalkene derivatives.

Methods

Reagents.

Tissue culture media, serum, and supplements were from Clonetics (Walkersville, MD). Hemin, LA, Act D, cycloheximide, diethylaminoethyl-dextran, and horse heart myoglobin were from Sigma. cPTIO and spermine NONOate (SNONOate) were from EMD Biosciences (San Diego). Purified 13-HPODE, ebselen, and butylated hydroxytoluene were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Anti-HO-1 antibody (SPA-896) was from Stressgen Biotechnologies (Vancouver, Canada), anti-human PPARγ antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and anti-actin antibody was from Sigma. For the preparation of oxymyoglobin, metmyoglobin was reduced by using sodium dithionite, desalted by exclusion chromatography on a Sephadex PD-10 column, and further oxygenated by equilibration with 100% oxygen as described (27).

Synthesis of LNO2 and Methyl Ester Derivative of LNO2.

Purification and quantitation of LNO2 was as described (3). LNO2 was derivatized to a methyl ester (Me-LNO2) by adding 1 ml of boron trifluoride/methanol (Pierce) to 30 μmol LNO2 for 6 min at 50°C. The reaction mixture was extracted by using the Bligh and Dyer method (39) and purified by using thin layer chromatography. Me-LNO2 concentration was calculated by chemiluminescent nitrogen detection (3).

Cell Culture.

Primary cultures of HAEC (Clonetics) were passaged as described (22) in endothelial basal medium containing 10% FBS, 6 μg/ml bovine brain extract, 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 50 μg/ml gentamycin, and 50 μg/ml amphotericin B. Studies were performed on confluent monolayers of HAEC over a range of five to seven passages. All cells were grown at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2. For all induction experiments, cells were incubated in 1% FBS-containing medium. Control cells were treated with the lipid vehicle methanol at concentrations used for fatty acid derivatives (<0.1% vol/vol).

Northern and Western Blot Analysis.

RNA and protein were extracted from cultured cells and analyzed as described (20). Purified RNA (3 μg per lane) was electrophoresed, blotted onto a nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia), and probed for human HO-1 or GAPDH. Autoradiographs were scanned on a Hewlett–Packard Scanjet 4C by using photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), and densitometry was performed by using nih scion image 4.02 software (Scion, Frederick, MD). Whole-cell protein was lysed in RIPA buffer and quantitated by using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), and 15 μg of total protein was electrophoresed on a 12% Tris-Glycine SDS/PAGE gel. Freshly isolated rat aortic rings (1 mm) were treated with control (methanol) or 25 μM LNO2 for 2, 4, 8, 12, or 16 h and lysed by homogenization in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors. After transfer to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore) HO-1 and actin were detected by using 1:5,000 dilutions of primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. Protein was visualized by using the ECL chemiluminescent detection system (Amersham Pharmacia).

Plasmid Constructs and Transient Transfection Analysis.

pHOGL3/11.6 and pHOGL3/4.5 luciferase expression plasmids containing −11.6 and −4.5 kb, respectively, of the human HO-1 promoter were constructed as described (22, 40). Transient transfections with equimolar amounts of the plasmids were performed using the diethylaminoethyl-dextran method and a batch transfection protocol (40). Lysates were assayed for luciferase activity by using a luciferase assay kit (Promega).

Immunofluorescence.

Freshly isolated rat aortic rings from Sprague–Dawley rats were treated with either methanol (control) or 25 μM LNO2, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and mounted on slides. Immunohistochemistry was performed on sections by using anti-HO-1 (SPA 895, Stressgen Biotechnologies) as primary antibody (1:1,000 dilution) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) (1:200 dilution). Nonimmune rabbit IgG was used as a negative control. Slides were viewed under a Leica microscope, and images were captured by using simple pci software (Compix, Cranberry Township, PA).

LNO2 Decay and Mass Spectrometry.

LNO2 (3 μM) was decayed in 100 mM phosphate buffer containing 100 μM diethylenetriaminepentaacetate (pH 7.4) at room temperature. At given times, an aliquot was removed, [13 C]LNO2 internal standard was added, and lipids were extracted (39). The organic phase was dried down and resuspended in methanol, and the remaining LNO2 was quantitated by means of LC-tandem mass spectrometry (4000 Q trap, Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex) as described (3).

Data Analysis.

Results are from at least two to three independent experiments, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM. For the luciferase data, analyses were performed by using ANOVA and the Student–Newman–Keuls test. All results are considered significant at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL068157 (to A.A.), T32 HL07457 (to P.R.S.B.), and HL58115, HL64937, and HL077100 (to B.A.F.); an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship (to F.J.S.); and a Parker B. Francis fellowship (to K.E.I.).

Abbreviations

- 13-HPODE

13(S)-hydroperoxy-octadecadienoic acid

- Act D

actinomycin D

- cPTIO

2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide

- DFO

deferoxamine

- HAEC

human aortic endothelial cells

- HO-1

heme oxygenase 1

- LA

linoleic acid

- LNO2

nitrolinoleic acid

- Me-LNO2

LNO2 methyl ester

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- SNONOate

(Z)-1-{N-[3-aminopropyl]-N-[4-(3-aminopropylammonio)butyl]-amino}-diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Ignarro L. J. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2002;53:503–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Donnell V. B., Eiserich J. P., Chumley P. H., Jablonsky M. J., Krishna N. R., Kirk M., Barnes S., Darley-Usmar V. M., Freeman B. A. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999;12:83–92. doi: 10.1021/tx980207u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker P. R., Schopfer F. J., Sweeney S., Freeman B. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11577–11582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402587101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Donnell V. B., Freeman B. A. Circ. Res. 2001;88:12–21. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coles B., Bloodsworth A., Eiserich J. P., Coffey M. J., McLoughlin R. M., Giddings J. C., Lewis M. J., Haslam R. J., Freeman B. A., O’Donnell V. B. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:5832–5840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim D. G., Sweeney S., Bloodsworth A., White C. R., Chumley P. H., Krishna N. R., Schopfer F., O’Donnell V. B., Eiserich J. P., Freeman B. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:15941–15946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232409599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schopfer F. J., Lin Y., Baker P. R., Cui T., Garcia-Barrio M., Zhang J., Chen K., Chen Y. E., Freeman B. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2340–2345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408384102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham N. G., Kappas A. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2005;39:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maines M. D. Annu Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997;37:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sassa S. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2004;6:819–824. doi: 10.1089/ars.2004.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeney V., Balla J., Yachie A., Varga Z., Vercellotti G. M., Eaton J. W., Balla G. Blood. 2002;100:879–887. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balla G., Jacob H. S., Balla J., Rosenberg M., Nath K., Apple F., Eaton J. W., Vercellotti G. M. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:18148–18153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brusko T. M., Wasserfall C. H., Agarwal A., Kapturczak M. H., Atkinson M. A. J. Immunol. 2005;174:5181–5186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durante W. Vasc. Med. 2002;7:195–202. doi: 10.1191/1358863x02vm424ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryter S. W., Morse D., Choi A. M. Sci. STKE. 2004:RE6. doi: 10.1126/stke.2302004re6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foresti R., Green C. J., Motterlini R. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 2004:177–192. doi: 10.1042/bss0710177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stocker R., Yamamoto Y., McDonagh A. F., Glazer A. N., Ames B. N. Science. 1987;235:1043–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.3029864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inguaggiato P., Gonzalez-Michaca L., Croatt A. J., Haggard J. J., Alam J., Nath K. A. Kidney Int. 2001;60:2181–2191. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakao A., Neto J. S., Kanno S., Stolz D. B., Kimizuka K., Liu F., Bach F. H., Billiar T. R., Choi A. M., Otterbein L. E., Murase N. Am. J. Transplant. 2005;5:282–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal A., Shiraishi F., Visner G. A., Nick H. S. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1998;9:1990–1997. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9111990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal A., Balla J., Balla G., Croatt A. J., Vercellotti G. M., Nath K. A. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:F814–F823. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.4.F814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill-Kapturczak N., Voakes C., Garcia J., Visner G., Nick H. S., Agarwal A. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:1416–1422. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000081656.76378.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouton C., Demple B. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32688–32693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.42.32688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang M., Croatt A. J., Nath K. A. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279:F728–F735. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.4.F728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motterlini R., Foresti R., Intaglietta M., Winslow R. M. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:H107–H114. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durante W., Kroll M. H., Christodoulides N., Peyton K. J., Schafer A. I. Circ. Res. 1997;80:557–564. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schopfer F. J., Baker P. R., Giles G., Chumley P., Batthyany C., Crawford J., Patel R. P., Hogg N., Branchaud B. P., Lancaster J. R., Jr, Freeman B. A. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:19289–19297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarez-Maqueda M., El Bekay R., Alba G., Monteseirin J., Chacon P., Vega A., Martin-Nieto J., Bedoya F. J., Pintado E., Sobrino F. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21929–21937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenacre S. A., Ischiropoulos H. Free Radical Res. 2001;34:541–581. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiva S., Moellering D., Ramachandran A., Levonen A. L., Landar A., Venkatraman A., Ceaser E., Ulasova E., Crawford J. H., Brookes P. S., et al. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 2004:107–120. doi: 10.1042/bss0710107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalyanaraman B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11527–11528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404309101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marx N., Duez H., Fruchart J. C., Staels B. Circ. Res. 2004;94:1168–1178. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127122.22685.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J. D., Tsai S. H., Lin S. Y., Ho Y. S., Hung L. F., Pan S., Ho F. M., Lin C. M., Liang Y. C. Life Sci. 2004;74:2451–2463. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duckers H. J., Boehm M., True A. L., Yet S. F., San H., Park J. L., Clinton Webb R., Lee M. E., Nabel G. J., Nabel E. G. Nat. Med. 2001;7:693–698. doi: 10.1038/89068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishikawa K., Sugawara D., Wang X., Suzuki K., Itabe H., Maruyama Y., Lusis A. J. Circ. Res. 2001;88:506–512. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.5.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lima E. S., Di Mascio P., Rubbo H., Abdalla D. S. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10717–10722. doi: 10.1021/bi025504j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lima E. S., Di Mascio P., Abdalla D. S. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:1660–1666. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200467-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubbo H., Radi R., Anselmi D., Kirk M., Barnes S., Butler J., Eiserich J. P., Freeman B. A. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:10812–10818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill-Kapturczak N., Sikorski E., Voakes C., Garcia J., Nick H. S., Agarwal A. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;285:F515–F523. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00137.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]