Abstract

We examined the requirement of λ recombination functions for marker rescue of cryptic prophage genes within the Escherichia coli chromosome. We infected lysogenic host cells with λimm434 phages and selected for recombinant immλ phages that had exchanged the imm434 region of the infecting phage for the heterologous 2.6-kb immλ region from the prophage. Phage-encoded activity, provided by either Red or NinR functions, was required for the substitution. Red− phages with ΔNinR, internal NinR deletions of rap-ninH, or orf-ninC were 117-, 12-, and 5-fold reduced for immλ rescue in a Rec+ host, suggesting the participation of several NinR activities. RecA was essential for NinR-dependent immλ rescue, but had slight influence on Red-dependent rescue. The host recombination activities RecBCD, RecJ, and RecQ participated in NinR-dependent recombination while they served to inhibit Red-mediated immλ rescue. The opposite effects of several host functions toward NinR- and Red-dependent immλ rescue explains why the independent pathways were not additive in a Rec+ host and why the NinR-dependent pathway appeared dominant. We measured the influence of the host recombination functions and DnaB on the appearance of oriλ-dependent replication initiation and whether oriλ replication initiation was required for immλ marker rescue.

MARKER rescue recombination to produce gene substitutions involves exchanges within regions of homology straddling a marker of interest. Strong modern evidence for the shuffling of phage gene modules in nature is provided by the stx phages and prophages of Escherichia coli, which share the genome organization of bacteriophage λ (Brüssow et al. 2004). Early λ workers identified phage-prophage marker rescue, where an infecting λ was capable of rescuing a gene present on a homologous cryptic prophage in a lysogenic cell. Signer and Weil (1968) used a spot test involving the rescue of an h (unspecified host range) marker from rec+ cells with a cryptic λ prophage (deleted for a large portion of prophage, including the imm region) that was infected by λhλ, and λh recombinants were selected on host cells that were resistant to infection by λhλ but sensitive to λh. Using this assay, Signer and Weil (1968) were able to screen hydroxylamine-treated infecting phage for deficiency in marker rescue. Several mutants with reduced ability to rescue prophage markers were subsequently mapped as recombination-defective red mutants. Echols and Gingery (1968) recovered λsus+ recombinants that were formed by marker rescue between an infecting λsus phage and a defective prophage in a lysogen. Both studies concluded that Red functions of λ were required for phage-prophage marker rescue in E. coli hosts defective for the host recA function. The λ Red-dependent recombination activity (reviewed by Stahl 1998; Kuzminov 1999; Court et al. 2002) depends upon the expression of λ genes exo and bet (or Redα, Redβ; combined, Red) along with gam. Red-dependent recombination is initiated by double-strand breaks, and when marked Red+ λ phages infect cells blocked for DNA replication, the λ × λ exchanges are focused near the cos ends, the only site of an initiating double-strand break (Tarkowski et al. 2002). Murphy and co-workers (Murphy 1998; Murphy et al. 2000) constructed an E. coli strain in which the cellular recBCD genes (Smith 2001) were replaced with exo-bet and placed under lac promoter control. They found that the λ activities supported recombination between the cellular chromosome and linear DNA fragments at an elevated level. Recombination in these ΔrecBCD cells, lacking Gam, depended upon Exo and Beta, was greatly reduced in recA mutants, and required host recombination genes recQ, recO, recR, recF, and ruvC, but not recJ or recG (Murphy 1998; Poteete et al. 1999; Murphy et al. 2000; Poteete and Fenton 2000). The λ Red functions can facilitate chromosomal engineering, i.e., substituting or disrupting genes in an E. coli chromosome or plasmid (Yu et al. 2000; Court et al. 2002). In the absence of E. coli methyl-directed mismatch repair activity, the inheritance of markers from single-strand DNA oligonucleotides required only the Bet function (Constantino and Court 2003).

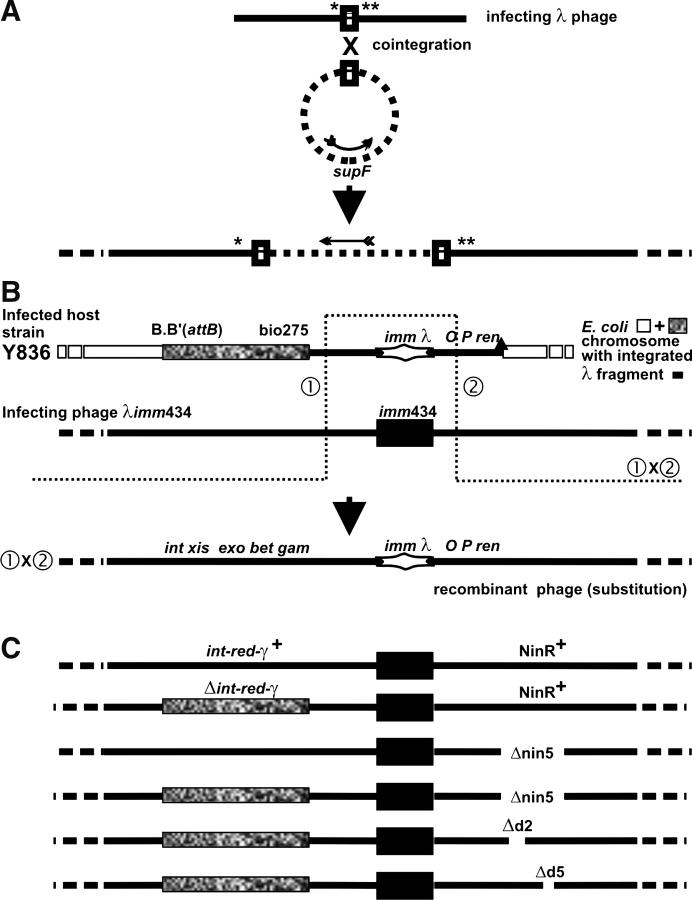

The co-integration of a plasmid into a phage, each sharing limited DNA homology, is shown as a single reciprocal crossover addition reaction (Figure 1A). King and Richardson (1986) and Shen and Huang (1986) found that packaged plasmid-phage co-integrates were formed by homologous recombination proceeding predominantly via the E. coli RecBCD pathway (reviewed by Kowalczykowski et al. 1994; Stahl 1998; Kuzminov 1999) when cells were infected with λ int− red− or Δint-gam phages sharing limited DNA sequence homology with a small plasmid carried within the cell. Hollifield et al. (1987) found that the formation of phage-plasmid co-integrates by Δint-gam phage Charon 4A (Blattner et al. 1977) depended on an encoded phage function mapping between λ genes P and Q within the NinR (Kröger and Hobom 1982) interval, defined by deletion Δnin5 and including the genes ren (Toothman and Herskowitz 1980) and nine open reading frames designated ninA–ninI (Daniels et al. 1983). They identified the rap function (recombination adept with plasmid) that mapped to orf204 (ninG gene) as being required for RecBCD pathway-mediated formation of phage-plasmid co-integrates. Even though Charon 4A was Δnin5, it encoded a similar determinant to rap that mapped within phage Φ80-derived sequences included in the cloning vector. The rap product (Hollifield et al. 1987; Stahl et al. 1995; Tarkowski et al. 2002) represents a branch-specific endonuclease that targets recombination intermediates generated in vivo and in vitro (Sharples et al. 1998, 1999). It can function as a genuine Holliday junction resolvase when presented with DNA substrates containing sufficient homology at the crossover (Sharples et al. 2004) and can substitute for the E. coli RuvC Holliday junction resolvase in λ Red recombination (Poteete et al. 2002). Yet another λ recombination function removed by Δnin5 was localized by Sawitzke and Stahl (1992) to orf146 (ninB gene) and termed orf because it could complement single mutations in the host genes recO, recR, and recF in recBC sbcB sbcC cells and thus function in RecF-dependent pathway crossovers between two co-infecting phages. Orf, with a monomer molecular mass of 16.6 kDa, was found to have pleiotropic effects on recombination, replication, and repair in E. coli. Orf suppresses the mutant phenotype not only of recF, recO, and recR, but also of ruvAB and ruvC (Poteete and Fenton 2000; Poteete et al. 2002; Poteete 2004).

Figure 1.—

(A) Homologous recombination between common sequence (rectangle) in phage and plasmid forming a phage-plasmid co-integrate structure (see text). Shen and Huang (1986) and Hollifield et al. (1987) used infecting phages that carried amber mutations in both λ genes A and B and were deleted for recombination functions int-xis-exo-bet-gam and the genes within the NinRλ region, which were substituted by another set of genes from NinΦ80. (B) Phage-prophage marker rescue of the immλ genes from a cryptic prophage (lacking a cos site) within the bacterial chromosome by an infecting imm434 phage. The open rectangles are DNA strands of a circular E. coli chromosome; solid lines are λDNA, as infecting phage or as cryptic prophage within E. coli chromosome; the solid rectangle is imm434; the stretched diamond structure is immλ; the stippled rectangle is bio275 substitution of E. coli DNA for the λ prophage genes int-cIII in the Y836 chromosome (and in infecting phages in C); the solid triangle on map of Y836 represents the Δ431 deletion removing rightward of λ prophage genes and adjacent chromosomal genes. The actual λ bases that were deleted or substituted are described in materials and methods. The drawing is to scale, except that the sizes of the imm434 and immλ intervals were made equal when imm434 was smaller by ∼1.2 kb. (C) Maps of infecting phages used in Tables 2–5. The deletion nin5 on infecting phage encroached on the interval of λ base homology to the right of the imm434 marker (B) between the cryptic prophage and the infecting phage, reducing it from ∼2519 (or 2565) bp (with Δ431 endpoint) to ∼2257 bp. The bio275 substitution on the infecting phage increased base homology to the left of the imm434 marker: the 2281-bp λ homology was unchanged, but homology was increased by the size of the bio275 substitution (see Hayes et al. 1990) carried on both prophage and infecting Δint-red-gam phage.

The intercrossing between two phage genomes is routinely drawn as a single splice reaction. Motamedi et al. (1999) demonstrated efficient homologous recombination between co-infecting int-gam-defective ΔNinR phages in rec+ hosts, showing that the host could provide needed recombination functions for phage-phage recombination and that the Red or NinR phage activities were not required. This observation supported a prior report by Stahl et al. (1995) that Rap function had no effect on the frequency of recombination between co-infecting phages sharing DNA homology, i.e., λ × λ exchange in an infected cell. In Red-mediated λ × λ crosses occurring when λDNA replication was blocked, Tarkowski et al. (2002) showed that the NinR products Orf and Rap influenced end focusing at double-strand breaks, but that Δnin5 had little or no effect on the outcome of such crosses in a recA− host.

This study was undertaken on the basis of observations from a rapid marker rescue test (functional immunity assay: Hayes and Hayes 1986; Hayes 1991) in which cells with a cryptic immλ prophage were stabbed to a fresh overlay plate containing cells lysogenized with λimm434 plus added free λimm434cI phage. Marker exchange between the cryptic prophage and the infecting λimm434cI phage (Figure 1B) yielded λimmλ recombinant phage that were revealed by a lysis spot (up to a 0.5-cm radius) surrounding the stabbed colony formed in the cell lawn of the λimm434 lysogen. The formation of immλ recombinant phages arose even when the stabbed cells (with cryptic immλ prophage) carried a null mutation in the key host recombination functions recA (trace lysis), recB, recD, recG, recJ, and ruvC or were double null mutants recA recD, recD recF, and recF recJ. In these crosses, the ∼1.4-kb imm434 DNA interval on the infecting phage (Figure 1C) was substituted by rescue of the heterologous ∼2.6-kb immλ DNA interval (which included the additional genes rexA-rexB) present in the cryptic λ prophage (K. Asai and S. Hayes, unpublished results). We examined whether rescue of the immλ region depended solely upon gene products encoded by the infecting phage. We found that λ's Red or its NinR each function in the absence of the other to support immλ exchange. The host requirements for the Red- or Nin-mediated immλ rescue differed significantly. The two systems were partially competitive, rather than additive, when both were expressed. We monitored the influence of DnaB and host recombination functions on DNA replication from oriλ to assess the participation of prophage replication initiation in immλ rescue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria:

E. coli strains are shown in Table 1. Strain Y836 (infected host drawn in Figure 1B) carries a cryptic prophage, is SA500 F− his87 relA1 strA181 (λbio275 cI[Ts]857 Δ431), and was made from Y832 (Hayes and Hayes 1986) derived from SA431 (Adhya et al. 1968; Stevens et al. 1971), which is a derivative of SA302 [AM3100 strr his87 (λcI[Ts]857)], itself a λ-lysogen of SA500 F− his87 relA1 strA181 (Hayes 1991). The cI repressor (CI) in these strains, in addition to being temperature sensitive (Ts), carries an Ind mutation (Hayes and Hayes 1986). Y836 was made by replacing the genes int-cIII (Daniels et al. 1983) in Y832/SA431 with bio275 DNA (Figure 1B) from the transducing phage λbio275 (Hayes and Hayes 1986; Hayes et al. 1990). Both strains Y836 and Y832/SA431 are deleted for the NinR functions (Kröger and Hobom 1982; Daniels et al. 1983; Cheng et al. 1995) by Δ431, where the left endpoint of Δ431 is between 40,764 and 40,810 bp λDNA (Hayes 1991) within orf146 (ninB). The variants of Y836 were made by P1vir transduction of appropriate markers. The recA character of the donor alleles and the recA transductants was demonstrated by showing that Fec− λ-phage, e.g., those defective for exo-bet-gam, as λΔint-red-gam imm434 (λbio275imm434), did not form plaques on these recA hosts. In contrast, the recD recA variant permitted efficient plating by Fec− λ phage (Amundsen et al. 1986). The grpD55 marker (Saito and Uchida 1978) that was moved into Y836 from W3350 grpD55 malF::Tn10 was genetically mapped to dnaB (Bull and Hayes 1996) and shown by sequence analysis (M. Horbay and S. Hayes, unpublished results) to be an allele of dnaB.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains

| Bacterial strain | Relevant genotype | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| W3350A (= W3350) | F−lac3350 galK2 IN(rrnD-rrnE) | Hayes and Hayes (1986) |

| W3350(λimm434-T) | Strong imm434 CI activity | Hayes and Hayes (1986) |

| TC600 | thr1 leuB6 fhuA21 lacY1 glnV44 | Bachmann (1987) (from C600) |

| e14− glpR200 thi1 supE | ||

| N100 | recA | S. Hayes collection |

| SA500 | F−his87 relA1 strA181 tsx83(?) | Hayes (1991) (see text) |

| SA431 | SA500(λcI[Ts]857 Δorf146-chlA) | Adhya et al. (1968); Stevens et al. (1971) |

| SA439 | SA500(λcI[Ts]857 ΔP-chlA) | Adhya et al. (1968); Stevens et al. (1971) |

| Y832 | SA500(λcI[Ts]857Δ431=orf146-chlA) | Hayes (1991); Hayes et al. (1990) |

| Y836 | SA500(λbio275 cI[Ts]857 Δ431 | Hayes and Hayes (1986); Hayes et al. (1990) |

| B832 | C600 arg::Tn5 nusAhy302 | F. W. Stahl |

| recD1009 suII | ||

| FC40 (= SMR624) | Δ(srlR-recA)::Tn10 | Harris et al. (1994); S. M. Rosenberg via H. Bull |

| SMR692 | recD6001::miniTn10-kan | Harris et al. (1994); S. M. Rosenberg via H. Bull |

| FWS-A354 (= SMR1) | recB21 argA::Tn10 sbcA | Stahl et al. (1980); S. M. Rosenberg via H. Bull |

| SZ635/Szigety | 594 r−m+ruvC53 eda51::Tn10 | Sharples et al. (1990); S. M. Rosenberg via H. Bull |

| DPB271 | MG1655 recD1903::miniTn10 | Biek and Cohen (1986); S. M. Rosenberg via H. Bull |

| MVM401 | recF400::Tn5 sulA::Mud1 cam | Madiraju and Clark (1991) |

| N2731/SMR600 | recG258::miniTn10-kan | Lloyd and Buckman (1991); S. M. Rosenberg via H. Bull |

| JC12-123/FWS-A548 | AB1157 recJ284::Tn10 | Lovett and Clark (1985); S. M. Rosenberg via H. Bull |

| W3350 grpD55 | grpD55 (allele of dnaB) |

Bull and Hayes (1996); M. Horbay and S. Hayes, unpublished results) |

| malF3089::Tn10 | ||

| SMR572 | C600 Δ(srlR-recA)::Tn10 [pRP42] | S. M. Rosenberg via H. Bull |

| Y836[pCI+] | AmpRimmλ CI+ high copy | M. Horbay, this laboratory |

| TC600[pRP42] | AmpRimm434 CI+ | K. Asai, this laboratory |

| W3350[pRP42] | AmpRimm434 CI+ | K. Asai, this laboratory |

| N100[pRP42] | AmpRimm434 CI+ | A. Chu, this laboratory |

| Y836 grpD55 | grpD55 (allele of dnaB) malF::Tn10 | K. Asai, this laboratory |

| Y836 ΔrecA | recA (ΔsrlR-recA306::Tn10) | K. Asai, this laboratory |

| Y836 recB | recB21 argA::Tn10 | K. Asai, this laboratory |

| Y836 ruvC | ruvC53 eda51::Tn10 | K. Asai, this laboratory |

| Y836 recD | recD1903:: miniTn10 | K. Asai, this laboratory |

| Y836 ΔrecA recD | recA (ΔsrlR-recA306::Tn10) | K. Asai, this laboratory |

| recD6001::miniTn10-kan | ||

| Y836 recD recF | recD1903::miniTn10 recF400::kan | K. Asai/N. Pastershank, this laboratory |

| Y836 recF | recF400::Tn5 | N. Pastershank, this laboratory |

| Y836 recF recJ | recF400::Tn5 recJ284::Tn10 | N. Pastershank, this laboratory |

| Y836 recJ | recJ284::Tn10 | N. Pastershank, this laboratory |

| Y836 recG | recG258::miniTn10-kan | K. Asai, this laboratory |

Plasmids:

pCH1 includes λ bases 34,449–41,732 (Hayes et al. 1997). pHB30nl42-9 (abbreviated pCI+) was derived from pHB30 (Bull 1995), which includes pBR322 (bases 375–4286) and λcI[Ts]857 (bases 34,499–34,696, 36,965–38,103, and 38,814–40,806; see Figure 2B). pCI+ was a cI[Ts]857 to cI+ (λ 37,742 T to C) revertant (isolated and sequenced by M. Horbay) of pHB30. It expresses sufficiently high levels of CI repressor to prevent the plating of λcI mutants and λvir (data not shown). pRP42 is AmpR ColE1 and was from M. Ptashne via SMR/HB (Table 1) and expresses the imm434 CI+ repressor. Cells with pRP42 infected at 39° with λcI72 yielded no λimm434 recombinants (frequency <1 × 10−8) when scored on TC600(λ) lysogens. Plasmids pTP914 and pTP915 were from A. R. Poteete. Plasmid pTP914 (Poteete et al. 2002) is AatII-galK (N-terminal end) pmac (TTTACA:-35; TATAAT:-10; RBS) rap SacI KanR from Tn903-galK (N-terminal end) BamHI pBR322:ori-bla, where the ApaI-pmac-rap-SacI interval was cloned into pTP838 (Murphy et al. 2000), and in pTP915 gfp replaces rap. Poteete et al. (2002) reported that the Rap+ phenotype in pTP914 was unaffected by the presence or absence of the lac inducer IPTG, suggesting a basal level of expression of rap from pmac.

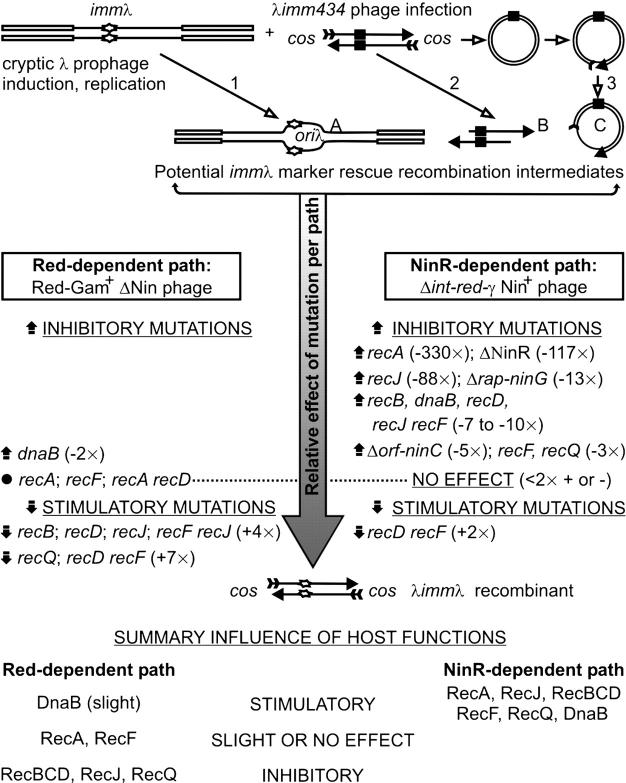

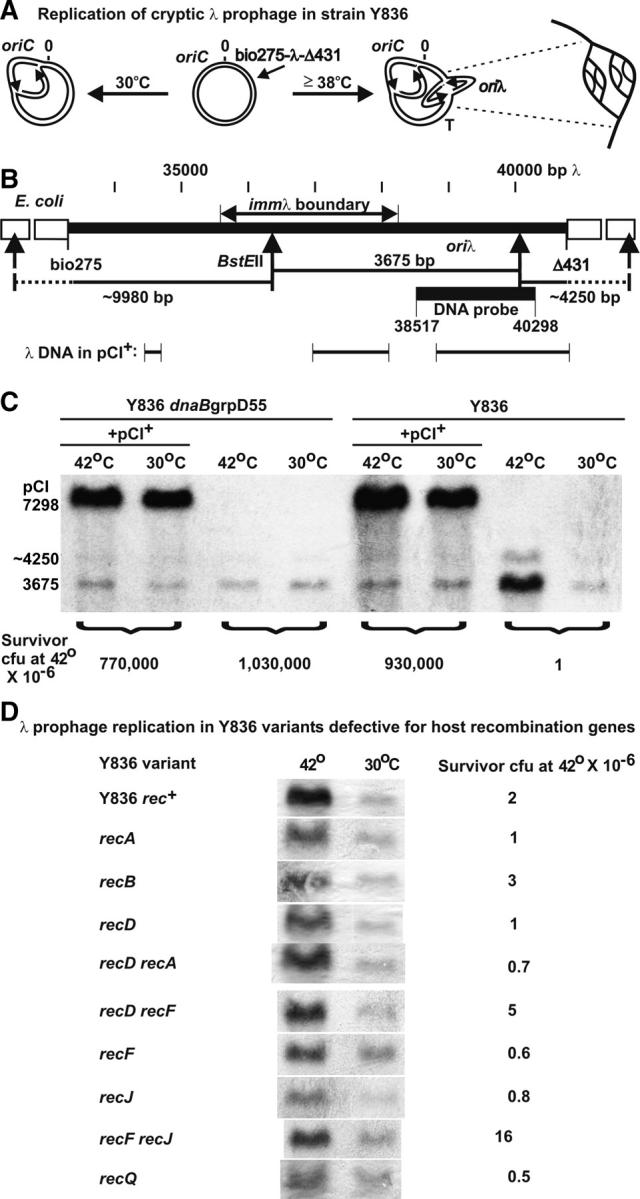

Figure 2.—

Assay for prophage replication initiation from oriλ. (A) The nonexcisable cryptic λ fragment inserted (short arrow) within the E. coli chromosome remains repressed at 30° where the prophage repressor is active. Shifting cells to ≥38° inactivates the CI857 repressor for λ prophage transcription and replication initiation from oriλ. Multiple λ bidirectional replication initiation events from oriλ generate the onion-skin replication structure drawn at right. (B) λDNA (thick solid line) fragment within the E. coli chromosome (open boxes), BstEII restriction sites within λ and the E. coli chromosome showing bands generated by cleavage (Hayes et al. 1990), and the region amplified to prepare a DNA probe. (C) Assay for replication initiation from oriλ upon shifting culture cells to 42° to induce the cryptic prophage. Cells with plasmid pCI+ are not derepressed for λ transcription or oriλ replication at 42°, permitting a comparison between any chromosomal increase for cells shifted for 1 hr at 42° with oriλ replication initiation arising from the derepressed cryptic prophage in Y836 cells without the plasmid that were shifted for 1 hr to 42°. (See text for discussion of survivor CFU at 42°.) (D) The influence of host recombination defects on λDNA synthesis initiated from oriλ.

Phages:

λΔnin5 (Hayes and Hayes 1986) was used for introducing the nin5 deletion into the imm434 phages. λimm434 is λimm434 cI as described in Hayes et al. (1998) (lysate 668a). λimm434 Δnin5 was made by crossing λΔnin5 × λbio275 imm434 Δnin5. λbio275 imm434 Δnin5 was prepared by crossing λΔnin5 × λbio275 imm434 cIBG[Ts]. λbio275 imm434 cIBG[Ts] was prepared by crossing λimm434 cIBG[Ts] (Hayes et al. 1998) × λbio275. (Thus, all of the imm434 phages, except λimm434 cI, were cIBG[Ts] and formed clear plaques at 37°.) λcI[Ts]857 Δd2 (stock MMS1892) and λcI[Ts]857 Δd5 (stock MMS1891) were from F. W. Stahl. λimm434 Δd2 was prepared by crossing λbio275 imm434 Δnin5 × λcI[Ts]857 Δd2. λimm434 Δd5 was prepared by crossing λbio275 imm434 Δnin5 × λcI[Ts]857 Δd5. λbio275 imm434 Δd2 was prepared by crossing λbio275 imm434 Δnin5 × λimm434 Δd2. λbio275 imm434 Δd5 was prepared by crossing λbio275 imm434 Δnin5 × λimm434 Δd5. The phages employed for marker rescue assays are diagrammed in Figure 1C. The nusA strain distinguishes phages with Δnin5, which are able to form plaques on it, from phages that cannot, i.e., λ wild type or phages with Δd2 or Δd5 (F. W. Stahl, personal communication). In the experiments reported here, the int-xis-hin-exo-bet-gam-kil gene interval (representing λ bases 27,731–∼33,303; Daniels et al. 1983) on some λimm434 infecting phages, or within the cryptic immλ prophage in strain Y836, was replaced (“Δint-red-gam”) with bio275 E. coli chromosomal DNA present on specialized transducing phage λbio275. Fec− phages with bio275 gene replacements do not form plaques on recA hosts. Phage λimm434 (Kaiser and Jacob 1957) carries a substitution of nonhomologous phage 434 DNA for a 2.66-kb immλ DNA region (35,584–38,245 bp λ) present in phage λ and in the cryptic λ prophage (Daniels et al. 1983). Each imm region encodes the respective immunity-specific genes cI and cro and the promoters pL and pR, except the immλ also includes genes rexA-rexB (1.28 kb not present in imm434). Phages designated ΔNinR carry the nin5 deletion of DNA bases 40,503–43,307, including ren-ninA–ninI (Daniels et al. 1983; Hollifield et al. 1987); Δd2 removes λDNA bases 40,943–41,810, including the C-terminal half of orf (ninB) and most of ninC from the N-terminal end, and Δd5 removes λDNA bases 42,925–43,183, including the C-terminal end of rap (ninG) and most of ninH from the N-terminal end (Hollifield et al. 1987).

Assay for replication initiation from induced cryptic λ prophage:

Single-colony isolates of strain Y836 and 13 variants were inoculated into tryptone broth (TB; 10 g Bacto tryptone, 5 g NaCl/liter) and grown overnight to saturation. Duplicate 20-ml subcultutures made from 1/100 culture dilutions were prepared and grown in a shaking water bath at 30° to midlog (A575 ∼ 0.35) in fresh TB. Cell aliquots were diluted in buffer (0.01 m NaCl and 0.01 m Tris HCL, pH 7.8) and spread on TB agar plates incubated at 30° and 42° for 48 hr to determine cell titer and cell viability (frequency of survivor clones) upon induction of the cryptic prophage. One of the duplicate subcultures at midlog was induced for expression of the genes on the cryptic λ prophage by shaking the culture for 15 sec at 60° and then placing it in a shaking 42° water bath for an additional 60 min. The parallel 30° culture was grown for an additional 60 min at 30°. At the end of the 60-min growth period, DNA was prepared from the 30° and 42° culture cells using the QIAGEN (Chatsworth, CA) DNAeasy kit that can process 2 × 109 cells. A culture volume equivalent to 2 × 109 cells was processed per DNA sample per filter. Duplicate DNA preparations were prepared for each culture sample at 30° and 42°. The duplicate DNA samples were combined, an aliquot was diluted 1/10 in TE* buffer (0.01 m Tris HCl, pH 7.6 or 8.0, 0.001 m Na2EDTA), and the DNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometer. Aliquots of the DNA estimated at 6.0 μg were ethanol precipitated and the pellets resuspended in 16 μl TE* for use in Southern blot analysis. A digoxigenin-dUTP (Dig)-labeled λDNA probe was prepared by amplifying pCH1 plasmid DNA (300 ng) using PCR primers L22 (λ bases 5′-38517–38534) and R24 (λ bases 5′-40298–40281) and the Dig Hy Prime DNA labeling detection kit (Roche Applied Science). The DNA probe band (Figure 2B) from the PCR was purified by electrophoresis on a 0.7% agarose gel, extracted using the QIAGEN gel extraction procedure, eluted, and concentrated to 2.0 μg/32 μl. The extracted band was converted to a hybridization probe using the Dig-labeling procedure. The DNA probe concentration was estimated from spot coloration on a filter to be ∼25 ng/μl. Each DNA preparation (2 μg), from cultures of Y836 and variants, was digested with BstEII at 60° and run on a 0.7% agarose gel, with 1 μg of λcI72 DNA digested with BstEII per gel as a control for band size. The gels were processed for blotting to GeneScreen Plus (DuPont, Wilmington, DE) filter paper. The Southern blots were hybridized using the Dig-labeled DNA probe at a concentration of 25 ng/ml of hybridization solution and bands were visualized using antidigoxigenin-AP according to the Dig Hy Prime labeling/detection protocol.

Marker rescue assays for immλ recombinants:

The recombination event involved the rescue of a 2.6-kb nonhomologous region of prophage DNA that is flanked by homologous regions of ∼2 kb shared by both the prophage and the infecting phage. The infections were slightly varied from the procedure in Hayes et al. (1998). Phage of 5 × 108 were mixed with ∼1 × 108 cells, placed in an air incubator at 39° for 15 min, diluted 0.01 into TB, and shaken 90 min at the indicated infection temperature. The lysate was clarified and plated onto sensitive cells to assay total phage and onto imm434 cells to assay for immλ recombinants. All cultures were made from a fresh colony on a TB agar plate (TB + 11 g Bacto agar per liter) or plate containing the antibiotic(s) corresponding to the strain's resistance marker(s). The averaged results and standard errors are for multiple independent assays. The practical cutoff for marker rescue of immλ in the crosses was set to ≤1 × 10−5, considered a background value even when no immλ recombinant PFU were obtained. Recombinant immλ phages were detected by plaque formation on W3350 or TC600 host cells lysogenized by λimm434-T or transformed by plasmid pRP42. The immλ rescue frequency was determined by dividing the titer of the recombinants by the total phage titer for the clarified 90-min lysate obtained on sensitive TC600 cells.

RESULTS

Requirement of phage genes for immλ marker rescue:

We examined the phage requirement for rescuing immλ from the cryptic prophage in strain Y836 (Figure 1B) using λimm434 infecting phages (Figure 1C). Phage Δint-red-gam ΔNinR (Table 2, line Y836, column 5) essentially failed to support immλ marker rescue at 30° or 39°. Thus, phage-encoded activity is needed for gene swapping, and the E. coli recombination functions provided in the absence of the phage activities do not suffice. We term the phage-dependent acquisition of heterologous genes the kleptomania (KM) phenotype, since functions are acquired or replaced without selective necessity. The Int-Red-Gam+ functions, provided by λimm434 Δnin5 phage, or the NinR+ functions, provided by λbio275 imm434, independently supported rescue of immλ from the cryptic prophage (Table 2). This shows that λ encodes two distinct genetic mechanisms for the KM phenotype. Marker rescue of immλ was favored by the NinR+ functions acting alone and was 117-fold higher at 39° than the basal level observed with Δint-red-gam ΔNinR phage infection.

TABLE 2.

Marker rescue ofimmλ from cryptic prophage

| Infecting imm434 phagesa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected host strains | Red+ NinR+ | Red+ ΔNinR | Δint-red-gam NinR+ | Δint-red-gam ΔNinR |

| Y836b | 202 (37) | 139 (28) | 352 (92) | 3 (<1) |

| Y836 grpD55 | 22 (9) | 59 (1) | 44 (13) | 2 (1) |

| Y836 recA | 43 (6) | 102 (47) | ≤1 (<1) | ≤1 (<1) |

| Y836 recB | 24 (1) | 527 (332) | 35 (5) | 2 (<1) |

| Y836 recD | 128 (23) | 549 (245) | 50 (14) | ≤1 (<1) |

| Y836 recD recA | 197 (38) | 189 (50) | ≤1 (<1) | ≤1 (<1) |

| Y836 recD recF | 1283 (71) | 988 (154) | 683 (255) | 26 (4) |

| Y836 recF | 259 (32) | 135 (25) | 132 (23) | ≤1 (<1) |

| Y836 recF recJ | 582 (48) | 587 (82) | 38 (12) | 8 (6) |

| Y836 recJ | 763 (55) | 508 (117) | 4 (4) | ≤1 (<1) |

| Y836 recQ | 347 (37) | 928 (99) | 130 (23) | 12 (7) |

Frequency of immλ marker rescue from cryptic prophage in host (×10−5) for infections carried out at 39°. Standard error is shown in parentheses.

Designations used: Red+ NinR+, λimm434; Δint-red-gam ΔNinR, λbio275 imm434 Δnin5; Δint-red-gam NinR+, λbio275 imm434; and Red+ ΔNinR, λimm434 Δnin5.

Frequency of immλ marker rescue from cryptic prophage in Y836 (×10−5) for infections carried out at 30° for phages: Red+ NinR+, 7(3); Red+ ΔNinR, 19(2); Δint-red-gam NinR+, 39(20), and Δint-red-gam ΔNinR, 2(1).

NinR activities in Rec+ hosts:

The possibility that multiple NinR functions participate in NinR+-dependent immλ rescue was tested by infections with Δint-red-gam phages deleted within NinR for orf-ninC or for rap-ninH. Deletion of the NinR region by Δnin5 reduced immλ rescue by 117-fold (Table 2), whereas deletions of orf-ninC or of rap-ninH yielded 5-fold and 12-fold reductions (Table 3), suggesting the participation of the deleted functions, as well as that of unaccounted NinR activities, in immλ rescue. The very inhibitory effect of Δnin5 on marker rescue is probably not explained by its encroachment on the rightward recombination interval, i.e., shortening it ∼10% (Figure 1, B and C).

TABLE 3.

Influence of NinR region mutations Δd2 and Δd5onimmλ marker rescue

| Infecting Δint-red-gam imm434 phages

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Infected host strains | Δorf-ninC [Δd2]a | Δrap-ninH [Δd5]b |

| Y836 | 73 (10) | 28 (4) |

| Y836 recA | ≤1 (<1) | ≤1 (<1) |

| Y836 recB | 80 (16) | 21 (2) |

| Y836 recD | 83 (6) | 62 (10) |

| Y836 recD recA | ≤1 (<1) | ≤1 (<1) |

| Y836 recD recF | 2 (1) | 14 (2) |

| Y836 recF | 49 (3) | 51 (9) |

| Y836 recF recJ | 60 (6) | 15 (1) |

| Y836 recJ | 110 (16) | 35 (12) |

| Y836 recQ | 95 (7) | 37 (4) |

Frequency of immλ marker rescue from cryptic prophage in host (×10−5) for infections carried out at 39°. Standard error is shown in parentheses.

Phage λbio275 imm434 Δd2.

Phage λbio275 imm434 Δd5.

Y836 cells containing a pBR322-derived multicopy plasmid expressing rap (pTP914), or a gfp control (pTP915), were infected to determine if Rap made by the plasmid could complement for the λ functions removed by Δnin5, Δd5, Δd2, and even Δint-red-gam (Table 4). Adding the Gfp plasmid pTP915 to Y836 cells increased the background level for immλ rescue by phage Δint-red-gam ΔNinR by 4-fold and the Rap plasmid pTP914 increased the background >10-fold [i.e., background 3 in Y836, 12 in Y836(pTP915), and 32 in Y836(pTP914) cells]. The presence of Rap provided by pTP914 did not substitute for all of the functions removed by ΔNinR [i.e., comparing Y836(pTR914) infections by Δint-red-gam NinR+ and Δint-red-gam ΔNinR phages]; however, immλ rescue was complemented ∼8-fold [i.e., comparing Δint-red-gam Δrap-ninH infections of Y836(pTP914) and Y836(pTP915)]. Clearly, more than one NinR activity must be removed to incapacitate NinR-dependent immλ rescue, and Rap expression alone is insufficient to complement fully Δnin5 phages for the loss of NinR+-dependent immλ marker rescue. These findings further support a proposal that the NinR region encodes several functions that aid immλ rescue in an otherwise Rec+ host.

TABLE 4.

Rap participation andimmλ marker rescue

| Infected host strains

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Infecting imm434 phages | Y836a | Y836 [pTP914 Rap+]b | Y836 [pTP915 Gfp]b |

| Red+ ΔNinR | 139 (28) | 145 (15) | 155 (15) |

| Δint-red-gam NinR+ | 352 (92)c | 394 (43) | 267 (38) |

| Δint-red-gam ΔNinR | 3 (<1) | 32 (3) | 12 (2) |

| Δint-red-gam Δrap-ninH [Δd5] | 28 (4) | 86 (3) | 11 (2) |

| Δint-red-gam Δorf-ninC [Δd2] | 73 (10) | 132 (1) | 33 (9) |

Frequency of immλ marker rescue from cryptic prophage in host (×10−5).

The results shown each represent an average for two independent infection reactions conducted in parallel.

The result shown was for an average of seven independent determinations at different times.

Host and phage functions influencing phage-prophage marker rescue at 39°:

The influence of host recombination functions on the KM phenotype was examined. Do the mechanisms for immλ rescue involve the same key host recombination activities? We show that, in the absence of Red activity, the NinR-dependent immλ rescue activity: (i) was reduced by >300-fold and 88-fold, respectively, by mutations in the host genes recA and recJ; (ii) was reduced 7- to 10-fold by inactivation of the host genes recB or recD and by the modification (mutation grpD55) of dnaB; (iii) was reduced 2- to 3-fold by inactivation of recF and recQ. We also show that (iv) a recF defect can partially suppress the loss of recJ; (v) a recF defect suppresses and stimulates NinR-dependent recombination in the absence of recD, whereas each separate mutation was inhibitory; and (vi) as noted above, immλ rescue moderately, or partially, required NinR activities encoded within rap-ninH and orf-ninC. In contrast, in absence of NinR activity, the Red+ system activity: (i) appeared independent of defects in the host genes recA and recF; (ii) was stimulated 4-fold by defects in the host genes recB, recD, recJ, and by recF recJ double mutations; (iii) was stimulated 7-fold by defects in recQ and by recD recF double mutations; and (iv) was reduced (∼2-fold) by the grpD55 allele of dnaB.

The distinct requirements for the host functions strongly suggest that individual Red-dependent or NinR-dependent mechanisms support immλ rescue. The RecBCD complex activity was inhibitory to the Red-dependent activity, since immλ rescue was significantly stimulated in Red+ΔNinR phage infections of hosts defective for recB or recD (Table 2). In contrast, it was stimulatory to NinR recombination (recB− and recD− mutations were inhibitory). Similarly, RecQ activity stimulates NinR-dependent rescue (recQ− is inhibitory) and inhibits Red-dependent rescue (recQ− is stimulatory). RecJ powerfully stimulated NinR-dependent immλ rescue (recJ− was strongly inhibitory) but inhibited Red-dependent rescue (recJ− is stimulatory). RecF appears to have a slight stimulatory effect on NinR-dependent immλ rescue, but no effect on Red-dependent immλ rescue. The inhibitory effects of RecBCD and RecJ on Red-dependent immλ rescue appear to be independent since the increased level of immλ rescue was the same in recJ, recJ recF, recD, and recB mutants, also suggesting that the inhibitory effect of RecJ was independent of Recf. The inhibitory effect of RecBCD on Red-mediated immλ rescue increased in the absence of Recf.

NinR activities in Rec− hosts:

The influence of host mutations on immλ marker rescue by Δint-red-gam phages deleted for part of the NinR region was examined (Table 3). We observed two unanticipated results: (1) The deletion of orf-ninC or of rap-ninH suppressed the requirement of recJ for NinR+-dependent immλ rescue by 27- and 9-fold, respectively (i.e., compared to Δint-red-gam NinR+ infection of Y836 recJ, Table 2), and (2) there was a dramatic loss in immλ rescue in a recD recF host for infections by Δint-red-gam Δd2 or Δd5 compared to a Δint-red-gam NinR+ infection (Table 2), and the levels were even lower than those for the Δint-red-gam ΔNinR infection. We noted earlier that RecF was not required for Red activity, but in the absence of RecD, proved somewhat inhibitory to both Red- and NinR-dependent immλ rescue. Was the level of RecF inhibition magnified by removal of the orf-ninC or rap-ninH genes within NinR? (Δd2 and Δd5 do not reduce the size of the recombining interval as both lie to the right of the interval between immλ and Δ431; see Figure 1.)

Prophage replication initiation from oriλ stimulates immλ rescue by infecting imm434 phage:

λ prophage replication initiation and gene expression are repressed by the prophage CI857 repressor in strain Y836 and its variants for cells grown at 30°. However, upon shifting the cells to ≥38°, the repressor is thermally denatured and transcription initiates from the λ promoters pL and pR, the early genes N and cro-cII-O-P are expressed, and bidirectional replication is initiated from oriλ within gene O (Figure 2A). Hayes (1979) observed an increase of 5–6 λDNA copies by 20 min after shifting cells with a nonexcising cryptic prophage λcI857ΔQ-Jb from 30° to 42°. Subsequently, C. Hayes and S. Hayes (unpublished results) found that oriλ-dependent replication forks induced in Y836 escaped bidirectionally into the contiguous E. coli chromosome, e.g., replicating the adjacent gal operon 15–20 kb left of attL, but stalled <200 kb from oriλ.

The initiation of oriλ replication in strain Y836 from the Δint-red-gam-kil prophage is shown by comparing DNA amplification of the 3675-bp BstEII fragment (Figure 2C), including oriλ, from thermally induced and noninduced cultures. Replication from oriλ escapes rightward as seen by amplification of the ∼4250-bp BstEII fragment (Hayes et al. 1990), which is mainly E. coli DNA. The addition of a multicopy pCI+ plasmid (7298-bp band, Figure 2C), expressing wild-type CI+ repressor, prevented oriλ replication initiation, i.e., amplification of the 3675-bp prophage fragment.

The initiation of divergent λ replication forks from the derepressed cryptic prophage in Y836 was accompanied by cell killing (Hayes et al. 1990), with the frequency of mutant survivor cells appearing at <10−5. Figure 2, C and D (separate assays and gels), shows survivor frequencies of Y836 CFU at 1 or 2 × 10−6, respectively. The addition of the pCI+ plasmid to Y836 cells prevented the loss in cell viability seen when the cells were shifted to 39° (Table 5) or 42° (Figure 2C) due to CI+ inhibition of λ prophage induction.

TABLE 5.

CI+ limitsimmλ rescue in Y836 at 39° following λimm434 infection

| Cell viability TB + Amp/TBa |

Recombination frequency (×10−5)c |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host Y836[pCI+]a | 30° | 39° | Colonies with plasmid loss at 39°b | 30° | 39° |

| Experiment 1 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0/220 | <0.3 | 0.5 |

| Experiment 2 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 0/220 | <0.1 | 1.4 |

Plasmid pCI+ is multicopy and expresses the cI+ gene encoding CI repressor of λ (see materials and methods).

Single colonies of Y836[pCI+] were prepared on TB + Ampicillin (100 μg/ml) agar plates, and a single colony was used to inoculate a culture of TB + Amp (100 μg/ml). Cell aliquots were infected and inoculated into TB (Experiment 1) or TB + Amp (100 μg/ml) (Experiment 2) for 90 min and the recombination frequency was determined. The same cell culture was subsequently plated on TB and on TB + Amp plates and incubated at 30° or 39°; the cell titer on TB + Amp plates was divided by the cell titer on TB plates. The growth of culture cells on TB plates does not require that cells maintain plasmid.

Single colonies on TB plates incubated at 39° were stabbed to TB + Amp and TB plates, respectively, for measuring the proportion of Y836 cells that had lost pCI+. In Experiment 1, all colonies from two dilution plates were picked.

The frequency of immλ recombinants from the crosses were determined by dividing the PFU titer on TC600[pRP42] cells by the PFU titer on TC600 cells.

The immλ rescue from Y836 cells infected at 39° by imm434 Red+ or NinR+ phages was seven- to ninefold higher than that for the parallel infections carried out at 30°, where the prophage genes are repressed (Table 2, 30° infection results in footnote “c”). We sought to determine if the increased frequency for immλ rescue was temperature specific or if it was influenced by transcription and oriλ replication initiation from the induced cryptic prophage. In Table 5 we show that (i) the plasmid loss from Y836[pCI+] cells grown at 39° was <0.5% (i.e., <1/220 colonies) per experiment, greatly limiting the possibility for immλ rescue from cells with induced prophages that had lost pCI+; (ii) the frequency of immλ recombinants formed at 39°, where both the Red+ and NinR+ recombination functions are expressed from λimm434 (which is insensitive to the CIλ repressor), was 212-fold below that for the infection of Y836 cells (without plasmid) by λimm434 at 39°; and (iii) Y836[pCI+] cells were 7-fold more inhibitory for immλ rescue at 39° than wereY836 cells infected at 30° (Table 5 and footnote c in Table 2). We conclude that oriλ-dependent replication initiation, or simply the derepression of λ gene expression, stimulates immλ rescue. Relevant to these observations, (i) the formation of λimm434 progeny phage particles released from the infected Y836[pCI+] cells was not reduced by pCI+, and (ii) viable immλ recombinants were not formed upon infecting W3350[pCI+] cells (data not shown). (Note that while pCI+ includes a small portion of λDNA within sieB left of immλ and the stretch O[C-terminal half]-P-ren right of immλ, it is deleted for the gene sequences sieB-N-pL-rexB-rexA and cro-cII-O (Figure 2B) so that any potential immλ recombinants rescued by λimm434 infection would be defective for growth.)

Replication initiation at oriλ requires an interaction between the λ P gene product and the host DnaB helicase (Mallory et al. 1990). Bull and Hayes (1996) transduced the mutation grpD55 from the original isolate (Saito and Uchida 1978) into W3350 and mapped it to dnaB. The grpD55 allele in the original isolate and in the allele moved into W3350 were sequenced and found to have identical dual missense mutations within dnaB (M. Horbay and S. Hayes, unpublished results). λ forms plaques (at high efficiency) on E. coli W3350 dnaBgrpD55 cells at 30° but not at the restrictive temperature of ≥39° (Bull and Hayes 1996), suggesting that the P:DnaB interaction required for oriλ replication breaks down at ≥39°. However, the dnaBgrpD55 allele does not significantly interfere with E. coli replication, since the cells can form a lawn on plates incubated at 39°–42°. The influence of dnaBgrpD55 on oriλ replication initiation in Y836 was examined. The dnaB allele strongly prevented oriλ replication initiation from the 3675-bp prophage fragment and suppressed cell killing by the induced λ prophage (Figure 2C).

The formation of immλ recombinants from infections of Y836 dnaBgrpD55 cells at 39° was reduced by nine-, eight-, and twofold in Red+ NinR+, Δint-red-gam NinR+, and Red+ ΔNinR phage infections (Table 2). We conclude that NinR-dependent immλ marker rescue is notably stimulated by replication initiation from the cryptic λ prophage fragment, whereas Red-dependent immλ rescue is much less dependent upon this event, suggesting again that λ encodes two mechanistically distinct recombination activities.

Studies being reported elsewhere (M. Horbay, C. Hayes and S. Hayes, unpublished results) are relevant to these observations. We asked if the absence of plaque formation on W3350 dnaBgrpD55 cells at 42° reflected the absence of a phage burst. We quantified plaque formation, free phage, and phage bursts from cells infected at MOI's of 0.01 and 5 at 30° and 42° with different oriλ phages and with the oriP22 hybrid phage λcI857(18,12)P22, which is insensitive to the influence of the dnaBgrpD55 allele. Recombination-driven phage replication was able to bypass the formal oriλ replication initiation step required for generating phage progeny if two homologous phage genomes entered a cell (M. Horbay, C. Hayes and S. Hayes, unpublished results), whereas the low MOI infections yielded no burst at the restrictive temperature, in agreement with the plaque assay results, but strong burst at 30°.

Formation of λimmλ recombinants:

We observed a >1000-fold difference in the frequencies of immλ recombinant phages formed upon varying the availability of phage and host functions (Table 2). At the low end, λΔint-red-gam NinR+ and ΔNinR phages produced no immλ recombinants upon infection of the recA host. Was this because immλ exchange occurred but the formation of a mature immλ particle required phage replication, because exchange between the infecting phage and prophage could not occur, or because there was an interdependence of replication and recombination? (We will discuss phage maturation without replication, i.e., the “free-loader” concept, below.) Hayes (1979)(see Furth and Wickner 1983) surveyed the requirement of host replication proteins for oriλ replication initiation. We are unaware of a similar assay for the influence of recombination proteins on replication initiation from oriλ. Since immλ marker rescue was diminished in the absence of oriλ replication initiation from prophage (i.e., by CI blocking prophage induction or the conditional defect of the dnaBgrpD55 allele), it was important to learn if host recombination functions influenced the appearance of replication initiation from oriλ.

We assayed oriλ replication from variants of Y836 with null mutations in host recombination genes (Figure 2D). In comparison to results seen for the Rec+ parent (Figure 2, C and D), the appearance of the onion-skin complex, representing multiple bidirectional replication initiation events (Figure 2A) arising from oriλ, was reduced in all of the variants, especially those with null alleles in recA, recB, recD, recQ, and recJ. Addressing the above question, oriλ replication initiation, albeit reduced, proceeded in the recA host. Thus, λΔint-red-gam phages should undergo oriλ replication initiation in this host, and thus the absence of immλ recombinants likely involves a requirement for RecA in phage-prophage exchange or maturation.

The most significant defect in DNA amplification from oriλ was seen in the Y836 recJ variant. (The strongest of three DNA amplification assays is shown in Figure 2D.) The recJ effect was suppressed partially by an additional null mutation in recF. Another experiment with Y836 recJ, which was identical to that for Y836 dnaBGrpD55 (Figure 2C, i.e., one culture set included pCI+ to visualize the oriλ prophage bands from 30° and 42° cultures with blocked prophage induction), revealed little if any amplification of the oriλ band (data not shown) from the induced Y836 recJ culture cells. These results suggest that recJ participates in the appearance of the onion-skin DNA complex initiated from oriλ (Figure 2, A and C). However, as described below, λ will form a plaque on a recJ host.

NinR and recJ influence plaque size:

The plaque size of λimm434 variants on E. coli hosts was measured in parallel at 30°. Plaques (>15/phage/host; ≤10% standard error) averaged 0.35 mm for Δint-red-gam NinR+ and Δint-red-gam ΔNinR phages on TC600 Rec+, and, respectively, 0.35 and 0.18 mm on Y836 and 0.22 and 0.16 mm on Y836 recJ. Clearly, the oriλ phages somehow replicate and mature on a host defective for recJ, but the extent of phage progeny released was compromised if we roughly assume that plaque size has some relationship to phage burst. The NinR+ activity doubled the plaque size of Δint-red-gam phage on Y836 and somewhat suppressed for the loss of recJ. Even in the presence of Red activity, the NinR region strongly contributed to plaque size, since in the same assay λimm434cI formed 0.90 and 0.53 mm plaques on TC600 and Y836 cells, whereas λimm434ΔNinR plaques were 0.44 and 0.18 mm, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We summarize in Figure 3 the influence of phage and host recombination functions on the rescue of a cryptic prophage immλ region by an infecting heteroimmune λimm434 phage. Major differences in the immλ marker rescue requirements were seen for infecting phages deleted for Δint-red-gam or for NinR. This suggests the occurrence of two distinct phage-encoded recombination pathways, the Red-dependent path and the NinR-dependent path. The deletion of both paths eliminated immλ marker rescue, even in the full presence of wild-type host recombination functions.

Figure 3.—

Summary of recombination factors influencing NinR-dependent and Red-dependent phage-prophage marker rescue. The open rectangles are DNA strands of circular E. coli chromosome; thin lines are λDNA, as infecting phage or as cryptic prophage within the E. coli chromosome; the solid rectangle is imm434; the stretched diamond is immλ; the feathered tails of arrows and the solid arrowheads respectively represent the 5′- and 3′-ends of phage DNA strands. The potential immλ recombination intermediates include: 1, replication D-loop formed within cryptic prophage after replication initiation from oriλ when the cells are placed at or above 39°, generating intermediate A; 2, exonucleolytic activity at 5′-ends of linear infecting λimm434 phage, resulting in 3′-single-stranded DNA overhangs generating intermediate B; 3, a nick is introduced into the circularized monomeric phage genome [or cos end(s) remains unligated], which is converted to a gap by the joint action of a DNA helicase and a single-stranded 5′–3′ exonuclease producing intermediate C.

To make sense of the many observations, we consider the following: Some mutants have unexpected phenotypes, for which we cannot rule out strain or allele-specific effects. However, in summary, the host recombination activities RecBCD, RecF, RecJ, and RecQ stimulated (participated in) NinR-dependent recombination while they served to reduce (inhibit) Red-mediated immλ marker rescue (Figure 3). RecA was essential for NinR, but had slight influence on Red-dependent recombination. RecF was not required for Red activity, but in absence of RecD, proved somewhat inhibitory to both Red- and NinR-dependent immλ rescue. The Red-dependent immλ rescue was mainly unaffected by host mutations in recA, recF, or a double mutant in recA recD, but was stimulated by host mutations in recB, recD, recJ, and recQ and double mutations in recF recJ and recD recF, whose products may compete for recombination intermediates generated by Red pathway functions. Thus, several of the host functions had opposite effects toward NinR- and Red-dependent immλ rescue, e.g., as noted, RecBCD stimulated NinR but inhibited the Red-dependent recombination. Because of these opposite effects, the combination of both Red+ and NinR+ recombination activities expressed by a λimm434 infecting phage (i.e., the sum of independent Red+- and NinR+-dependent frequencies) was not additive for immλ rescue in the Rec+ Y836 host. Due to the inhibitory effect of several of the host functions on Red and their stimulatory effect on NinR-dependent recombination, we suggest that most of the immλ rescue seen with the Red+ NinR+ infections of Rec+ Y836 cells is NinR+ dependent; i.e., NinR+ is the dominant pathway in a Rec+ host.

It was suggested that the λ Red functions Beta and Exo (double-stranded 5′-exonuclease) share functionality with RecA and RecJ (Corrette-Bennett and Lovett 1995). While RecA mediates recombination via single-strand invasion, Exo and Beta generate recombinants by a process called single-strand annealing (see Court et al. 2002), possibly analogous to double-strand break repair in yeast. Our results showing a fourfold stimulation of Red-dependent marker rescue (by ΔNinR phages) in the absence of recJ, which encodes a single-stranded 5′ exonuclease (Lovett and Kolodner 1989), agree with observations by Murphy (1998) and with the finding that RecJ participates in Red-mediated λ × λ recombination in the absence of Rap activity (Tarkowski et al. 2002).

The requirements for phage-prophage marker rescue have gone mainly unexplored since the studies by Echols and Gingery (1968) and Signer and Weil (1968), who suggested that λ's Int or Red functions support marker rescue recombination in a RecA− host. The results reported here agree and show that the Red-dependent pathway is capable of eliciting substantial immλ rescue in the absence of RecA activity. However, the investigators in the 1960s suggested that the host Rec+ functions could provide for marker rescue recombination in the absence of Red functions. This was unsupported by our results showing virtually no immλ phage-prophage marker rescue in the absence of the Red or the NinR functions encoded by phage λ. We explain the latter discrepancy by assuming that the marker rescue infection assays carried out in the absence of Red functions actually provided unrecognized NinR+ functionality within the infecting phages employed, which was attributed to the host Rec+ functions.

Hollifield et al. (1987) identified the NinR function rap as an essential requirement for phage-plasmid co-integration at a site of shared DNA homology (Figure 1A) using infecting phages deleted for int-gam. The Rap protein was identified as a Ser/Thr phosphatase (Voegtli et al. 2000) and as a Holliday junction resolvase (Sharples et al. 2004). We show that the nin5 deletion of NinR functions on a Δint-red-gam infecting phage was complemented partially by expressing rap from a plasmid within the infected cells. The deletion of rap-ninH on a Δint-red-gam infecting phage inhibited immλ recombination 9-fold, while similarly providing Rap from a plasmid within the infected cells increased immλ rescue. The partial complementation of both Δnin5 and Δrap-ninH deletions by Rap expressed from a plasmid indirectly implies that Rap is important for immλ rescue, but it is unlikely to be the only participating NinR function. An analogous infection with a Δorf-ninC phage similarly decreased immλ rescue (∼5-fold). Thus, the orf and/or ninC product contributes, along with Rap (and possibly NinH), to NinR-pathway-dependent recombination. Of relevance to this study, Stahl et al. (1995) reported a very modest (2.5-fold) effect of Rap on the frequency of apparent patch (substitution) recombinant formation between a plasmid and a phage whereas the production of co-integrate (apparent single splice or addition) products was stimulated 17-fold.

The formation of NinR-dependent immλ recombinants was far lower at 30° than at 39°. Two procedures that inhibited replication initiation from the cryptic prophage, i.e., the addition to cells of a CI+ plasmid or of the grpD55 allele of dnaB (both shown to prevent oriλ replication initiation), both reduced immλ marker rescue by 212- and 9-fold, respectively, at 39°. Thus, immλ marker rescue is enhanced by oriλ replication initiation from the cryptic prophage. The products of λ genes O-P participate in loading the host dnaB product at oriλ (Learn et al. 1997), contributing eventually to the open DNA complex represented by intermediate A in Figure 3, which likely is subjected to replicative inhibition (see Hayes and Hayes 1986) by CI due to a requirement for transcriptional activation of oriλ (Dove et al. 1969; Furth and Wickner 1983). An enhancement of immλ recombination due to the formation of intermediate A could involve DnaB driving branch migration (Kaplan and O'Donnell 2002). The greater inhibition of immλ rescue in Y836[pCI+] than in Y836 dnaBgrpD55 cells at 39° or in Y836 cells (with CI857 repressor) at 30° may result from excess CI+ severely inhibiting λ transcriptional derepression.

The amplification level of onion-skin replication was not a critical requirement for NinR-dependent immλ marker rescue, although its formation clearly proved of equal importance to the requirements for recB and recD. The accumulation of the onion-skin product of oriλ replication initiation was greatly reduced in the recJ host and was eliminated in the dnaBgrpD55 strain. Yet the recJ mutation was significantly more inhibitory to NinR-dependent immλ marker rescue than was the altered dnaB allele. Moderate oriλ replication accumulated as an onion-skin intermediate in strains defective for recA, recB, and recD, yet there was an absolute requirement of RecA and an intermediate requirement of RecB and RecD for NinR-dependent immλ rescue. recQ encodes a helicase that translocates in the 3′ → 5′ direction when bound to single-stranded DNA (Umezu et al. 1990). Amplification of the onion-skin product of oriλ replication initiation was minimal in recQ mutants, but there was less than a threefold reduction (observed in ∼30 separate assays) in the level of NinR-dependent immλ rescue.

The induction of oriλ-dependent replication from a cryptic prophage kills the host cell, probably by several mechanisms (Datta et al. 2005). Rare survivor cells include mutants with large deletions removing part of or the entire λ fragment (Hayes et al. 1990; Hayes 1991). The endpoints in 435 such deletions arising from cells with an induced λcI857Δ431 prophage were mapped and none of the deletion endpoints was at or near attL (Hayes 1991). Thus, the attractive possibility that the int product efficiently promotes unequal crossing over between att and secondary sites within the prophage or bacterial chromosome to generate deletions was unsupported. The int-cIII prophage segment in the λcI857Δ431 prophage was substituted in strain Y836 to reduce further the possibility for concerted illegitimate deletion of the prophage fragment. The appearance of immλ recombinants from λimm434 Δnin5 infections was ascribed to Red-dependent λ recombination activities, but also includes the potential for int-dependent attB × attP site-specific recombination driving marker rescue; however, we provide no further evidence for or against this possibility. We note that Enquist and Skalka (1973) found no evidence for Int-mediated recombination between circular monomers to produce packagable concatemers; i.e., no more phages were produced on infection of recA− cells with int+red− gam− point mutants than with λbio11 int− red− gam− phage. We consider unlikely the possibility that a significant fraction of immλ marker rescue is explained by illegitimate excision of the replicating cryptic prophage out of the chromosome, i.e., enabling the infecting λ to recombine with a prophage circle rather than with the chromosome. The excision of a λ fragment (circular or not) from a replicating cryptic prophage imbedded within the chromosome was not observed here by gel blotting studies that identified the single-copy 3675-bp oriλ fragment excised by BstEII from a noninduced prophage.

Whether promoted by Red or by NinR, mechanistically, the detection of immλ marker rescue from a chromosomal cryptic prophage, lacking cos, requires gene substitution and replacement of a functionally equivalent (although nonhomologous) DNA module in the imm434 infecting phage plus packaging of the recombinant genome to form a mature phage particle. Models for DNA substitution involve two independent splice events flanking immλ or a single invasion event extended by branch migration, leaving a large patch of unpaired DNA that is ultimately resolved into distinct daughter copies by replication. The quite different requirements for Red- vs. NinR-promoted immλ rescue suggest independent mechanisms.

The formation of mature immλ recombinant particles “should” also depend upon sufficient replication of the recombinant molecule to produce a molecular intermediate able to serve as a substrate for DNA packaging, i.e., one with two cos sites. Packaged phage genomes are occasionally formed from substrates with less than two cos sites (Little and Gottesman 1971; Yarmolinsky 1971; Enquist and Skalka 1973). Similarly, immλ lysogens grown in heavy medium and then infected with imm434 in light medium yielded some viable phage particles containing DNA (fully heavy repressed prophage) predominantly made before infection (Ptashne 1965); the thermal induction of a λ prophage in a lysogenic cell unable to synthesize DNA at the inducing temperature also yielded some infective centers, requiring the formation of a mature virus particle (Fangman and Feiss 1969). Several of the experiments described here included an infection of cells on which plaque formation was virtually abolished: (1) Δint-red-gam phage plated onto recA-defective hosts and (2) oriλ phage plated onto dnaB grpD55 host cells at restrictive temperature. In (1), the absence of plaque formation is explained by the “classical” Red-Rec bypass model (see Smith 1983; Amundsen et al. 1986). Linear multimers (concatemers) formed via late stage λ rolling-circle replication are destroyed by the ExoV activity of the RecBCD complex in the absence of Gam, and a dimer is not formed by recombination between two monomeric circles in the absence of RecA, resulting in the absence of a molecular substrate with two cos sites for λ genome packaging. recD null mutants (of recA+ cells) have a hyperrecombination phenotype (Kuzminov 1999). The introduction of a recD− mutation into a recA− host restores the ability of Red− phage to form a plaque on a recA host, somehow suppressing the destruction of linear concatemers by ExoV (Amundsen et al. 1986). Linear multimers are produced by plasmids in recBC sbcBC (ExoV- and ExoI-defective) cells and are formed by the rolling-circle type of plasmid DNA replication dependent upon the RecF pathway genes recA (Biek and Cohen 1986), recF, recJ (Cohen and Clark 1986; Silberstein and Cohen 1987), recO, and recQ (Kusano et al. 1989). Indeed, the link between accelerated concatemer formation and plasmid instability led to the identification of recD mutants (Biek and Cohen 1986).

Stahl et al. (1997) suggested that λDNA replicated in recA mutant cells is a good substrate for annealing, providing DNA ends, presumably as tips of rolling circles. We showed that defects in host recombination genes modulated the accumulation of the onion-skin replication product, suggesting that the recombination proteins are required for either oriλ replication or the stability of the accumulated DNA, a topic requiring further analysis. (For example, the product from the double recD recA or recD recF mutants is greater than that from the three single mutations.) We suggest that the onion-skin product is a target for host nucleases and that some of the DNA copies of this region are broken and degraded. Presumably, the broken ends arising from θ (oriλ) replication could stimulate recombination by serving as a substrate for strand invasion or by invading the replicon of the infecting phage. This may help explain why immλ marker rescue increased when the cryptic prophage was able to initiate oriλ replication at 39° and reduced when oriλ replication was blocked. No immλ recombinants were detected from λΔint-red-gam imm434 NinR+ infections of recA or recA recD hosts, even though oriλ replication should occur from prophage and infecting phage in both hosts, and in the recA recD host, linear concatemers should be stabilized. The absence of immλ recombinants for the λΔint-red-gam imm434 NinR+ infection of a recA recD host provides strong support for the requirement of RecA for NinR-dependent marker rescue, since neither replication nor the potential to form stable linear concatemers for genome packaging was limiting.

In plating situation (2) above, the absence of plaque formation by an oriλ phage on dnaBgrpD55 host cells at restrictive temperature is explained by an inability of the infecting phage to initiate replication, as observed. Nevertheless, when the oriλ infecting phages were NinR+ or Red+, mature immλ oriλ recombinants arose in the lysates of the infected dnaBgrpD55 cells. We offer two observations that demonstrate that these results are not without precedent:

Biophysical studies: McMilin and Russo (1972)(p. 55) reported, “under conditions which block λ DNA duplication, unduplicated λ DNA can mature, including molecules which have recombined in the host.” Stahl et al. (1972) extended this observation and coined the term “free-loader” phage to describe phage produced under replication-blocked conditions, whose synthesis depended upon bacterial and phage recombination systems.

Infections at MOI >1: Sclafani and Wechsler (1981) showed that at low MOI (0.1) no λ phage particles were produced in cells lacking a functional dnaB product, yet at high MOI a significant proportion of the cells can produce phage. M. Horbay, C. Hayes and S. Hayes (unpublished results) found that oriλ replication initiation is needed for a phage burst when the MOI of the infecting phage is <1 (e.g., the situation in a plaque assay with many-fold excess cells to phage). But infections introducing two phage genomes per cell yield bursts of up to 30 phage/infected cell following infections into cells where oriλ replication is blocked.

From each of these four separate observations, we assume that recombination mechanisms can bypass the need for oriλ replication to produce a mature phage. (Motamedi et al. 1999 and Kuzminov 1999 discuss postulates for recombination intermediates initiating replication.) The immλ bursts, shown here to depend upon Red or NinR phage functions, suggest that phage-prophage recombination will permit the maturation of a phage particle in a host cell where both the prophage and the infecting phage are blocked for oriλ replication initiation. Similarly, plasmids of diverse origin sometimes generate open circular by-products with single-stranded tails, i.e., linear multimers, in cells defective for ExoV and ExoI (Cohen and Clark 1986; Silberstein and Cohen 1987). The dependence of plasmid linear multimer formation on the functional recA, recF, and recJ genes was interpreted to reflect integrative recombination between tails and plasmid circles operating as an additional mechanism for tail elongation (see Kusano et al. 1989). Silberstein et al. (1990) examined λ-mediated synthesis of plasmid linear multimers and proposed that (a) concatemer formation involved RecE, RecF, or Red pathway-dependent recombination between DNA double-stranded ends and (b) recombination-dependent priming of DNA synthesis at a 3′ OH end of an external, single-stranded DNA that invades a homologous sequence on a circular template. Recombination-independent models for switching from the early θ-mode to the late σ-mode of λ linear multimer replication include DNA synthesis at a 3′ OH end of a nicked strand and displacement of the 5′-end or the conversion of oriλ-dependent bidirectional θ-replication to unidirectional replication accompanied by a break in the lagging strand downstream from the replication fork remaining active.

Clark et al. (2001) described seven short boundary sequence intervals, each highly conserved per interval, which divided the metabolic regions of many lambdoid phages into six modules (Campbell and Botstein 1982). They proposed that the boundary sequences were “foci for genetic recombination” in lambdoid phages and served to assort the modules and to increase genetic mosaicism. BLASTP search results (Altshul et al. 1997) for the λNinR region reading frames reveal widely shared homologies with other phages and bacterial genomes. We propose that these NinR clusters (KM modules) have a role in stimulating exchanges between the boundary sequences of infecting phages and cellular prophages and thus participate in driving phage evolutionary diversity (Hendrix et al. 1999; Kameyama et al. 1999; Weisberg et al. 1999; Juhala et al. 2000; Johansen et al. 2001; Brüssow et al. 2004).

Acknowledgments

We thank H. J. Bull, A. R. Poteete, S. M. Rosenberg, F. W. Stahl, and M. Horbay for phage, plasmids, and bacterial strains. We are grateful for the participation of J. S. Booth, N. Pastershank, and H. Phillips during preliminary stages of this study; M. Horbay for sharing unpublished results; H. Bull for discussions on recombination models; and R. Slavcev for a BLASTP search of phage NinR genes. The Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada provided grant support.

References

- Adhya, S., P. Cleary and A. Campbell, 1968. A deletion analysis of prophage lambda and adjacent regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 61: 956–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang et al., 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen, S. K., A. F. Taylor, A. M. Chaudhury and G. R. Smith, 1986. recD, the gene for an essential third subunit of exonuclease V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83: 5558–5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backmann, B. J., 1987 Derivatives and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12, pp. 1192–1219 in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology, Vol. 2, edited by F. C. Neidhardt, J. I. Ingraham, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter et al. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- Biek, D. P., and S. N. Cohen, 1986. Identification and characterization of recD, a gene affecting plasmid maintenance and recombination in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 167: 594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner, F. R., B. G. Williams, A. E. Blechel, K. Denniston-Thompson, H. E. Faber et al., 1977. Charon phages: safer derivatives of bacteriophage lambda for DNA cloning. Science 196: 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüssow, H., C. Canchaya and W.-D. Hardt, 2004. Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68: 560–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull, H. J., 1995 Bacteriophage lambda replication-coupled processes: genetic elements and regulatory choices. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada.

- Bull, H. J., and S. Hayes, 1996. The grpD55 locus appears to be an allele of dnaB. Mol. Gen. Genet. 252: 755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A., and D. Botstein, 1982 Evolution of the lambdoid phages, pp. 365–380 in Lambda II, edited by R. W. Hendrix, J. W. Roberts, F. W. Stahl and R. A. Weisberg. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Cheng, S. C., D. L. Court and D. I. Friedman, 1995. Transcription termination signals in the nin region of bacteriophage lambda: identification of rho-dependent termination regions. Genetics 140: 875–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A. J., W. Inwood, T. Cloutier and T. S. Dhillon, 2001. Nucleotide sequence of coliphage HK620 and the evolution of lambdoid phages. J. Mol. Biol. 311: 657–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A., and A. J. Clark, 1986. Synthesis of linear plasmid multimers in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 167: 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, N., and D. L. Court, 2003. Enhanced levels of lambda Red-mediated recombinants in mismatch repair mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 15748–15753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrette-Bennett, S., and S. T. Lovett, 1995. Enhancement of RecA strand-transfer activity by the RecJ exonuclease of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 6881–6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court, D. L., J. A. Sawitzke and L. C. Thomason, 2002. Genetic engineering using homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36: 361–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, D. L., J. L. Schroder, W. Szybalski, F. Sanger, A. R. Coulson et al., 1983 Complete annotated lambda sequence, pp. 519–676 in Lambda II, edited by R. W. Hendrix, J. W. Roberts, F. W. Stahl and R. A. Weisberg. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Datta, I., S. Banik-Maiti, L. Adhikari, S. Sau, N. Das et al., 2005. The mutation that makes Escherichia coli resistant to λ P gene-mediated host lethality is located within the DNA initiator gene dnaA of the bacterium. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove, W. F., E. Hargrove, M. Ohashi, F. Haugli and A. Gupta, 1969. Replicator activation in lambda. Jpn. J. Genet. 44(Suppl.): 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Echols, H., and R. Gingery, 1968. Mutants of bacteriophage λ defective in vegetative genetic recombination. J. Mol. Biol. 34: 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enquist, L. W., and A. Skalka, 1973. Replication of bacteriophage λ DNA dependent on the function of host and viral genes. I. Interaction of red, gam, and rec. J. Mol. Biol. 75: 185–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fangman, W. L., and M. Feiss, 1969. Fate of λ DNA in a bacterial host defective in DNA synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 44: 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furth, M. E., and S. H. Wickner, 1983 Lambda DNA replication, pp. 145–173 in Lambda II, edited by R. W. Hendrix, J. W. Roberts, F. W. Stahl and R. A. Weisberg. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Harris, R. S., S. Longerich and S. M. Rosenberg, 1994. Recombination in adaptive mutation. Science 264: 258–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S., 1979. Initiation of coliphage lambda replication, lit, oop RNA synthesis, and effect of gene dosage on transcription from promoters PL, PR, and PR′. Virology 97: 415–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S., 1991. Mapping ethanol induced deletions. Mol. Gen. Genet. 231: 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S., and C. Hayes, 1986. Spontaneous λ mutations suppress inhibition of bacteriophage growth by nonimmune exclusion phenotype of defective λ prophage. J. Virol. 58: 835–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S., D. Duncan and C. Hayes, 1990. Alcohol treatment of defective lambda lysogens is deletionogenic. Mol. Gen. Genet. 222: 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S., H. J. Bull and J. Tulloch, 1997. The Rex phenotype of altruistic cell death following infection of a λ lysogen by T4rII mutants is suppressed by plasmids expressing OOP RNA. Gene 189: 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S., C. Hayes, H. J. Bull, L. A. Pelcher and R. A. Slavcev, 1998. Acquired mutations in phage λ genes O or P that enable constitutive expression of a cryptic λN+cI[Ts]cro− prophage in E. coli cells shifted from 30°C to 42°C, accompanied by loss of immλ and Rex+ phenotypes and emergence of a non-immune exclusion state. Gene 223: 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, R. W., M. C. M. Smith, R. N. Burns, M. E. Ford and G. F. Hatfull, 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriopages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 2192–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield, W. C., E. N. Kaplan and H. V. Huang, 1987. Efficient RecABC-dependent, homologous recombination between coliphage lambda and plasmids requires a phage Nin region gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 210: 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, B. K., Y. Wasteson, P. E. Granum and S. Brynestad, 2001. Mosaic structure of Shiga- toxin-2-encoding phages isolated from Escherichia coli O157:H7 indicates frequent gene exchange between lambdoid phage genomes. Microbiology 147: 1929–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhala, R. J., M. E. Ford, R. L. Duda, A. Youlton, G. F. Hatfull et al., 2000. Genomic sequences of bacteriophages HK97 and HK022: pervasive genetic mosaicism in the lambdoid bacteriophages. J. Mol. Biol. 299: 27–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, A. D., and F. Jacob, 1957. Recombination between related temperate bacteriophages and the genetic control of immunity and prophage localization. Virology 4: 509–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama, L., L. Fernandez, J. Calderon, A. Ortiz-Rojas and T. A. Patterson, 1999. Characterization of wild lambdoid bacteriopages: detection of a wide distribution of phage immunity groups and identification of a nus-dependent, nonlambdoid phage group. Virology 263: 100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, D. L., and M. O'Donnell, 2002. DnaB drives DNA branch migration and dislodges proteins while encircling two DNA strands. Mol. Cell 10: 647–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, S. R., and J. P. Richardson, 1986. Role of homology and pathway specificity for recombination between plasmids and bacteriophage λ. Mol. Gen. Genet. 204: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczykowski, S. C., D. A. Dixon, A. K. Eggleston, S. D. Lauder and W. M. Rehrauer, 1994. Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 58: 401–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, M., and G. Hobom, 1982. A chain of interlinked genes in the Nin region of bacteriophage lambda. Gene 20: 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano, K., K. Nakayama and H. Nakayama, 1989. Plasmid-mediated lethality and plasmid multimer formation in an Escherichia coli recBC sbcBC mutant. Involvement of RecF recombination pathway genes. J. Mol. Biol. 209: 623–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzminov, A., 1999. Recombinational repair of DNA damage in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage λ. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63: 751–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learn, B. A., S.-J. Um, L. Huang and R. McMacken, 1997. Cryptic single-stranded-DNA binding activities of the phage λ P and Escherichia coli DnaC replication initiation proteins facilitate the transfer of E. coli DnaB helicase onto DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 1154–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little, J. W., and M. Gottesman, 1971 Defective lambda particles whose DNA carries only a single cohesive end, pp. 371–394 in The Bacteriophage Lambda, edited by A. D. Hershey. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Lloyd, R. G., and C. Buckman, 1991. Genetic analysis of the recG locus of Escherichia coli K-12 and of its role in recombination and DNA repair. J. Bacteriol. 173: 1004–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett, S. T., and R. D. Kolodner, 1989. Identification and purification of a single-stranded-DNA-specific exonuclease encoded by the recJ gene of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86: 2627–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madiraju, M. V., and A. J. Clark, 1991. Effect of RecF protein on reactions catalyzed by RecA protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 19: 6295–6300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, J. B., C. Alfano and R. McMacken, 1990. Host virus interactions in the initiation of bacteriophage λ DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 265: 13297–13307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMilin, K. D., and V. E. A. Russo, 1972. Maturation and recombination of bacteriophage lambda DNA molecules in the absence of DNA duplication. J. Mol. Biol. 68: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamedi, M. R., S. K. Szigety and S. M. Rosenberg, 1999. Double-strand-break repair recombination in Escherichia coli: physical evidence for a DNA replication mechanism in vivo. Genes Dev. 13: 2889–2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. C., 1998. Use of bacteriophage λ recombination functions to promote gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180: 2063–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. C., K. G. Campellone and A. R. Poteete, 2000. PCR-mediated gene replacement in Escherichia coli. Gene 246: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteete, A. R., 2004. Modulation of DNA repair and recombination by the bacteriophage λ Orf function in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 186: 2699–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteete, A. R., and A. C. Fenton, 2000. Genetic requirements of phage λ Red-mediated gene replacement in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 182: 2336–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteete, A. R., A. C. Fenton and K. C. Murphy, 1999. Roles of RuvC and RecG in phage λ Red-mediated recombination. J. Bacteriol. 181: 5402–5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteete, A. R., A. C. Fenton and H. R. Wang, 2002. Recombination-promoting activity of the bacteriophage λ Rap protein in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 184: 4626–4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne, M., 1965. The detachment and maturation of conserved lambda prophage DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 11: 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]