THE GENERAL OPINION IS THAT THE DEATH RATE OF NEGROES is higher in the North than in the South. This is untrue. The crude death rates of the Negroes in the Northern cities are lower than those in the Southern cities… of the large cities, the eight highest death rates are Southern cities—Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans, Richmond, Norfolk, Nashville, St. Louis and Atlanta. Thirty deaths per 1,000 seems to be the dividing line between the Northern cities and the Southern, most of the Southern cities having a rate above 30, while most of the Northern cities have a rate below 30.

Chicago, with about the same population of Negroes as Charleston and Nashville, has less than one-half as many deaths per 1,000 as the former and two-thirds as the latter. New York, with about the same population as New Orleans, has about two-thirds as many deaths per 1,000; Norfolk has twice the rate of Indianapolis.

An analysis of the Negro population in these cities, however, gives the North a decided advantage, in that the number of children is less in the North than in the South and since the first five years of life have a very high mortality, that section having a smaller proportion of children all other things being equal, ought to show the lowest general crude death rate… .

Carrying the argument further, there are two matters of evidence which can not be controverted. (1) In the diseases peculiar to manhood, the North has no advantage but a real disadvantage since a larger proportion of the Negro inhabitants in the Northern cities is between the ages of 15 and 50, than is the case in the Southern cities. (2) Tuberculosis is a disease of adult life, attacking those chiefly past 15 years of age and is most prevalent between 20 and 30.

According to a bulletin published by the Illinois state board of health, 26.22 per cent of the deaths from all causes for persons between 20 and 50 in 1902–1903, were from consumption and nine-tenths of the deaths from consumption were of persons between these ages… four [cities] in the North: New York, Boston, Chicago and Cincinnati, have a [consumption death] rate above 500 per 100,000, while eight of the Southern cities, Washington, New Orleans, St. Louis, Atlanta, Nashville, Savannah, Charleston and Norfolk, have a rate about this number. Only one of the Southern cities falls below the rate of 400 per 100,000, while three of the Northern cities do… the North has no advantage which is purely statistical, i.e. relating to age distribution. Here again the Southern cities are in excess of the Northern cities… .

All of the foregoing argument shows that death rate in this country does not altogether depend upon climate; that it is a factor which can be easily overcome, and the Negroes of this generation are rapidly overcoming it. That there is something more important than climate, may be gained from the observation that almost uniformly the Northern white death rate, like the Northern Negro death rate, is lower than that of the South. Indeed the Negro Northern death rate in many places is lower than that of the whites in many Southern cities. The white death rates of Charleston and Savannah are higher than the Negro rate of Philadelphia, Indianapolis and Chicago. Charleston’s white rate is higher than Boston’s Negroes. The whites of New Orleans, Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, Atlanta, Mobile and Memphis are all higher than the Negroes of Chicago… .

A study of deaths by months in Philadelphia also tends to discredit the theory that Negroes are at a special disadvantage in the cold climate. The highest monthly average of deaths from all causes for five years for Negroes was in April, though January for whites. The third was July for both Negroes and whites. The lowest, September for Negroes and October for whites, while December was next lowest for Negroes.

For the past five years—1901 to 1905, inclusive, there were 1,589 deaths among Negroes from consumption, an average of 26.5 per month. Strange to say the highest average for any month during these five years was April, the next July and May, and the next October—every one of the winter months was below the average. For the five years the average deaths of consumption among Negroes for the month of October was less than April, December less than June, January less July, February slightly above August, March below September.

For pneumonia, inflammation of the lungs, we have the opposite: For the years 1901, 1902, 1903 there were 698 deaths or 19.4 per month. Above this average were January, February, the highest point, March, April, November and December, while below it were the summer months, May, June, July, August, September and October.

The point is that the season does not have any very materially different effect upon the Negroes than upon the whites, save that the total death rate from this disease is greater among Negroes all of the year round, but that there is not the greater difference in the winter months which might be expected.

Let us now come to the subject of the Northern Negroes’ general physical condition. For this purpose let us take a special city. That city is Philadelphia, and for many reasons. It is the largest, the oldest and most conservative city and is quite representative of the Negroes’ progress in the North, but comparisons with other cities will be made as are deemed necessary to the better understanding of the Philadelphia situation… .

The average death rate for Philadelphia for ten years from 1896–1905, inclusive, was 18.72 per 1,000, while the average for colored was 22.02 per 1,000a difference of 3.80 per thousand against the colored persons.

What is shown for Philadelphia here over a course of years also holds good for every Northern city… .

The causes of death of which Negroes form more than their part are in the following order: Syphilis leads with 20.5 per cent of the total deaths; then come marasmus, whooping cough, consumption, inanition, pneumonia, inflammation of the brain, child birth, typhoid fever, epilepsy, cholera infantum, still births, premature births, inflammation of the kidneys, dysentery, heart disease and Bright’s disease.

The diseases below the line, i.e., of which the Negro population die to a less proportion than they form of the entire population are anemia, erysipelas, diphtheria, cancer, alcoholism, old age, diabetes, apoplexy, sunstroke, fatty degeneration of the heart, fatty degeneration of the liver, softening of the brain, scarlet fever, scrofula; that is, in the deaths from 17 out of about 50 diseases the Negroes form more than the percentage they form of the total population. For most of these diseases the same is general in all the Northern cities of which I have information… .

The diseases of consumption and pneumonia, infantile marasmus, cholera infantum, inanition, heart disease are the diseases which take the Negroes away. From these diseases during the years of 1900, 1901, 1902, 1903, 3,284 persons died, or 51.1 per cent of the total deaths for these four years (6,424). Each year they constituted over half of the deaths.

If deaths from these causes had been at the same rate as the whites, the Negro general death rate would have been much less than the rate for the city.

Consumption is the chief cause of excessive death rate. One out of every six Negro persons who die in Philadelphia, dies of this disease, and probably five out of every seven who die between 18 and 28 die of this disease. It attacks the young men and women just as they are entering a life of economic benefit and takes them away. This disease is probably the greatest drawback to the Negro race in this country.

In 1900 there were 1,467 babies born in Philadelphia and 25 per cent died before they were one year old. Of every five persons who die in a year two are children under five years of age. The disease of cholera infantum, inanition and marasmus, which are simply the doctor’s way of saying lack of nourishment and lack of care, cause many unnecessary deaths of children… .

The undeniable fact is, then, that in certain diseases the Negroes have a much higher rate than the whites, and especially in consumption, pneumonia and infantile diseases.

The question is: Is this racial? Mr. Hoffman would lead us to say yes, and to infer that it means that Negroes are inherently inferior in physique to whites.

But the difference in Philadelphia can be explained on other grounds than upon race. The high death rate of Philadelphia Negroes is yet lower than the whites of Savannah, Charleston, New Orleans and Atlanta.

If the population were divided as to social and economic condition the matter of race would be almost entirely eliminated. Poverty’s death rate in Russia shows a much greater divergence from the rate among the well-to-do than the difference between Negroes and whites of America. In England, according to Mulhall, the poor have a rate twice as high as the rich, and the well-to-do are between the two. The same is true in Sweden, Germany and other countries. In Chicago the death rate among whites of the stock yards district is higher than the Negroes of that city and further away from the death rate of the Hyde Park district of that city than the Negroes are from the whites in Philadelphia.

Even in consumption all the evidence goes to show that it is not a racial disease but a social disease. The rate in certain sections among whites in New York and Chicago is higher than the Negroes of some cities. But as yet no careful study of consumption has been made in order to see whether or not the race factor can be eliminated, and if not, what part it plays.

The high infantile mortality of Philadelphia today is not a Negro affair, but an index of a social condition. Today the white infants furnish two-thirds as many deaths as the Negroes, but as late as twenty years ago the white rate was constantly higher than the Negro rate of today—and only in the past sixteen years has it been lower than the Negro death rate of today. The matter of sickness is an indication of social and economic position… .

We might continue this argument almost indefinitely going to one conclusion, that the Negro death rate and sickness are largely matters of condition and not due to racial traits and tendencies… .

With the improved sanitary condition, improved education and better economic opportunities, the mortality of the race may and probably will steadily decrease until it becomes normal… .

The Eleventh Atlanta Conference has made a study of the physique, health and mortality of the Negro American, reviewing the work of the first conference held ten years ago and gathered some of the available data at hand today.

The Conference notes first an undoubted betterment in the health of Negroes; the general death rate is lower, the infant mortality has markedly decreased, and the number of deaths from consumption is lessening.

The present death rate is still, however, far too high and the Conference recommends the formation of local health leagues among colored people for the dissemination of better knowledge of sanitation and preventive medicine. The general organizations throughout the country for bettering health ought to make special effort to reach the colored people. The health of the whole country depends in no little degree upon the health of Negroes.

Especial effort is needed to stamp out consumption. The Conference calls for concerted action to this end.

The Conference does not find any adequate scientific warrant for the assumption that the Negro race is inferior to other races in physical build or vitality. The present differences in mortality seem to be sufficiently explained by conditions of life; and physical measurements prove the Negro a normal human being capable of average human accomplishments.

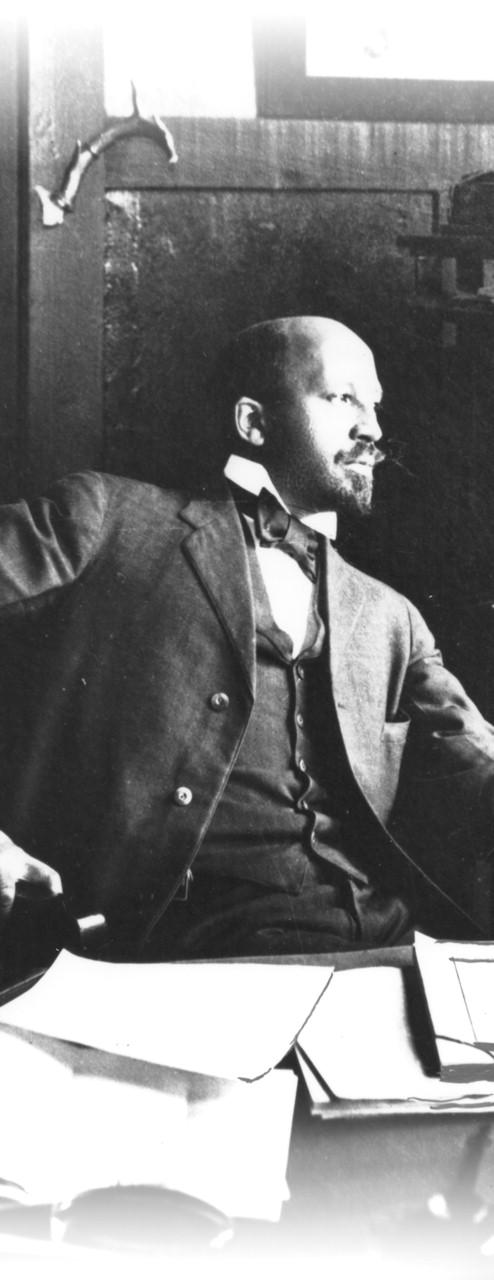

Figure 1.

Excerpted from W. E. Burghardt DuBois, ed. The Health and Physique of the Negro American. Report of a Social Study Made Under the Direction of Atlanta University; Together With the Proceedings of the Eleventh Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems, Held at Atlanta University, on May the 29th, 1906. Atlanta, Ga: Atlanta University Press; 1906.