Abstract

Objectives. We compared health insurance status transitions of nonimmigrants and immigrants.

Methods. We used multivariate survival analysis to examine gaining and losing insurance by citizenship and legal status among adults with the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey.

Results. We found significant differences by citizenship and legal status in health insurance transitions. Undocumented immigrants were less likely to gain and more likely to lose insurance compared with native-born citizens. Legal residents were less likely to gain and were slightly more likely to lose insurance compared with native-born citizens. Naturalized citizens did not differ from native-born citizens.

Conclusions. Previous studies have not examined health insurance transitions by citizenship and legal status. Policies to increase coverage should consider the experiences of different immigrant groups.

Health insurance coverage is an important predictor of preventive and therapeutic medical care.1,2 For example, Sudano and Baker found that individuals who had been uninsured at any time during the previous 2 years were less likely to obtain important preventive services, such as Papanicolaou tests and cholesterol tests, compared with individuals who had remained insured throughout the 2 years.2 Several studies have also found that uninsured individuals delay obtaining needed medical care, even putting off visits to a doctor when they are sick.3–6

Cross-sectional studies have repeatedly shown that immigrants are much less likely to be insured than are native-born Americans.7–10 In the 1997 Current Population Survey (CPS), 34% of immigrants were uninsured compared with only 14% of native-born Americans.10 Studies have also found that insurance coverage for immigrants differs by citizenship status.7,10,11 In the 1997 CPS, 44% of noncitizen immigrants were uninsured compared with 19% of immigrants who were US citizens10; in the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), 51% of noncitizens without a green card were uninsured compared with 32% of noncitizens with a green card, 17% of naturalized citizens, and 11% of those who were native born.7 Because most surveys, such as the CPS, do not collect information on legal status,9,10,12 previous studies estimated rather than measured coverage for undocumented immigrants. These estimates suggest that undocumented immigrants have a much higher uninsured rate than do other groups. For example, basing their estimate on 1999 CPS data, Brown et al.9 estimated that 65% of undocumented immigrants were uninsured in California. Lack of health insurance compromises the ability of immigrants to access care. Insured immigrants had significantly better access to care than did uninsured immigrants in an analysis of the 1997 National Survey of America Families.12

The 2 main sources of health insurance are employment-based health insurance and public programs.13 Past research suggests that immigrants have less insurance coverage primarily because their socioeconomic circumstances make them unlikely to be eligible for these types of health insurance. For example, the lower average educational attainment of immigrants makes it likely that they will find lower-status jobs without insurance coverage and jobs in industries that do not typically offer employment-based health insurance.7,14,15 Immigrants are also more likely to be ineligible for certain public insurance programs. The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act prohibited federal funding of Medicaid for legal immigrants during their first 5 years in the United States—although some states, including California, have used state funds to fill the gap.16,17

Past research on immigration and health insurance coverage has been almost exclusively cross-sectional and was focused on insurance status at a single point in time. These analyses are inherently limited, because they ignore the process of gaining or losing coverage over time. The few studies that have examined insurance transitions do not consider whether immigrant status has an independent effect on such transitions.18,19 Whether immigration status affects health insurance transitions above and beyond immigrants’ socioeconomic status has important policy implications. For example, if immigrants are less likely to move from an uninsured to an insured status even when occupation and socioeconomic status are controlled, expanding employment-based coverage will not solve the problem of insurance coverage for immigrants.

This article makes 3 key contributions. First, it was the only study to date to compare the dynamics of health insurance coverage of immigrants and nonimmigrants. Second, we examined whether immigrant status itself affects coverage after other factors affecting insurance eligibility were controlled. Third, in contrast to previous studies, we used information on legal status to compare insurance coverage for undocumented immigrants with coverage for legal immigrants, naturalized citizens, and native-born Americans.

METHODS

Data Source

Analyses were based on wave 1 of the 2000–2001 Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (LAFANS-1). LAFANS-1 was a survey of adults, children, and neighborhoods in a stratified probability sample of census tracts in Los Angeles County. The 1652 census tracts in Los Angeles County were divided into very poor, poor, and non-poor strata based on the percentage of the population living in poverty in each census tract. A total of 65 tracts were sampled: 20 each from the very poor and poor strata and 25 from the nonpoor stratum. Within each sampled tract, 40–50 dwelling units were selected at random, with an oversampling of households with children. Within each household, LAFANS-1 randomly selected 1 adult (aged 18 years and older) for interview. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish. Two thousand six hundred twenty-three adult respondents were interviewed. Our analysis was limited to adult respondents younger than 65 years—the age of eligibility for Medicare. Twenty-three hundred respondents had health insurance information and were under 65 years of age. The analysis sample size was reduced to 2130 after we excluded respondents with missing information on the independent variables.

More than half of the LAFANS-1 sample was Latino (principally of Mexican origin), and the sample included sizable numbers of first- and second-generation immigrants (Latino, White, and Asian) as well as nonimmigrants. For more details, see Sastry et al.20

Variable Definition

An interactive month-by-month event history calendar (EHC) covering the 2-year observation period before the interview was completed for each adult respondent. Interviewers asked a series of questions to capture the start and end dates of periods within various domains such as place of residence, employment, and public assistance receipt (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, General Relief, Supplemental Security Income, or Food Stamps). After the questions were completed for all domains, respondents were asked about health insurance coverage. The beginning and end dates of each period of insurance or uninsurance were recorded, until all months in the 2-year observation period were accounted for. For each period, respondents reported whether they were insured and the type of health insurance or reason for uninsurance. The questions included specific health insurance programs, such as Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid) and Healthy Families (State Children’s Health Insurance Program).21

Discrete time survival analysis, based on person-months observed for each respondent, was used to estimate the effects of static and time-varying covariates on changes in health insurance coverage.22 Two separate analyses were conducted. One analysis of uninsured immigrants and nonimmigrants examined the relative risk of becoming insured during each month of observation. The second analysis of insured immigrants and nonimmigrants examined the relative risk of losing insurance during each month of observation.

Our central focus was legal and citizenship status for immigrants. LAFANS-1 determined whether respondents were born in the United States and, if not, their current citizenship status. Noncitizens were asked to indicate whether they had permanent residency (a “green card”), a valid visa, asylum, or temporary protected status. Respondents were classified into 4 groups: native-born citizens, naturalized citizens, legal residents (documented noncitizens), and undocumented immigrants. We used the term “legal residents” to refer to those with green card, visa, or other legal status who had not become naturalized citizens. Immigration and citizenship status were reported only at the time of interview.

Covariates in the analysis consisted of basic demographics such as gender, ethnicity, and whether the interview was conducted in Spanish or English (as an indication of English language ability). We expected that English speakers would be more likely to obtain health insurance, because they would have an easier time navigating the insurance system. These covariates were obtained at the time of the interview and were included as time-invariant covariates.

Covariates that affect one’s eligibility for employment-based insurance, such as educational attainment, age, employment and occupation, and marital status, were also included.7,13,18 Education was only collected at the time of interview and is a covariate that does not vary with time. LAFANS-1 collected monthly data during the year 2 EHC on all other covariates associated with employment-based coverage—all of these covariates varied with time. We examined 2 occupation categories: high status (i.e., white and blue collar occupations that include health insurance benefits) and low status (service and other occupations that generally do not include insurance benefits).

Finally, characteristics associated with public program eligibility, such as family income, having a minor child, pregnancy, and receipt of public assistance, were included. Analyses included the log of family income and non-housing assets. In California, some low-income parents with minor children and pregnant women are eligible for Medi-Cal.13,23 Therefore, the analysis included time-varying variables indicating whether the respondent had any minor children of different ages and whether the respondent had a new child or was pregnant.

Receipt of public assistance (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, General Relief, Supplemental Security Income, Food Stamps) was included as a proxy for knowledge of and access to the public welfare system. Because recipients of some public benefits are automatically eligible for Medicaid, decisions about public assistance and public insurance coverage may be made jointly (i.e., receipt of public assistance is potentially endogenous). To assess this potential effect, models were also run without public assistance. Omitting public assistance produced no change in the results.

Health status was collected at the time of interview. Early models included health status at interview, but none of the coefficients were statistically significant and none were included in the models presented here.

Unlike earlier studies, LAFANS-1 collected information on the duration of insurance periods in progress at the start of the EHC. Thus, our models included exposure months for each respondent during all periods that fell within the 2-year observation period, including the full duration of exposure for periods that began before the start of the EHC. This approach is comparable to an increment–decrement life table in which individuals’ exposure is counted beginning at the duration first observed when they entered the EHC.24 For example, if an individual who has already been uninsured for 5 years enters the 2-year EHC, the duration of this uninsured period began at 60 months. This approach allowed us to examine both shorter and longer periods. For immigrants who arrived in the United States during the observation period, exposure was counted from the date of immigration. Duration within a period was coded as a set of dummy variables: 0–1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 4–5, 5–10, 10–20, and greater than 20 years. Duration categories were chosen on the basis of visual inspection of the survival curves. Likelihood ratio tests comparing a discrete functional form with other functional forms such as Weibull and exponential showed that models with duration in discrete form produced the best fit.

Analyses

Statistical analyses were done in Stata.25 Multivariate logit models predicting gaining and losing insurance were used to obtain relative risks adjusted for socioeconomic characteristics. Variables controlling for the over-sampling of poor households and households with children and variables related to nonresponse were included in the model.26

RESULTS

Health Insurance Transitions Among Immigrants

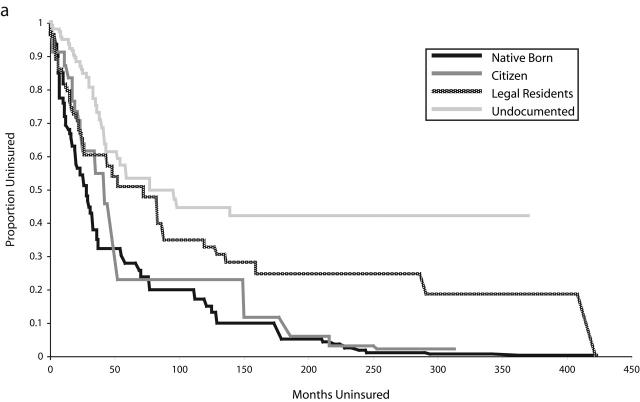

As has been the case in previous studies, the foreign-born population in LAFANS-1 was less likely to be insured. At interview, 69% of undocumented immigrants, 37% of legal residents, 22% of naturalized citizens, and only 17% of US native-born respondents were uninsured (Table 1 ▶). These differences could also be seen throughout the 2-year observation period. Among respondents who were uninsured at the start of the period, 82% of both undocumented immigrants and naturalized citizens and 75% of legal residents remained uninsured for the entire 2 years, compared with 65% of native-born citizens. Figure 1a ▶ shows the survival curve for immigrants and nonimmigrants not insured at the beginning of the EHC (i.e., proportion remaining uninsured at each month). For ease of presentation, only the first health insurance period in the observation period (i.e., 86% of all insurance periods) is included in Figure 1 ▶. Undocumented immigrants and legal residents remained uninsured much longer than did native-born and naturalized citizens. By 29 months, 50% of the native-born respondents had obtained insurance, and by 43 months, more than 50% of the naturalized citizens were covered. Legal residents and undocumented immigrants did not reach the 50% insured mark until 73 and 78 months, respectively.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Uninsured Immigrants and Nonimmigrants Aged 18–64 Years at Time of Interview: Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey, 2000–2001 (n = 2130)

| Health Insurance Coverage | |||

| Uninsured, % or Median (No.)a | Insured, % or Median (No.) | Total % (No.) | |

| Citizenship status | |||

| Undocumented immigrants | 69 (287) | 31 (90) | 11 (377) |

| Legal residents | 37 (199) | 63 (254) | 16 (453) |

| Naturalized citizens | 22 (59) | 78 (256) | 16 (315) |

| US native born | 17 (142) | 83 (843) | 57 (985) |

| Language of interview | |||

| English | 19 (215) | 81 (1111) | 76 (1326) |

| Spanish | 53 (472) | 47 (332) | 24 (804) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Latino | 42 (562) | 58 (638) | 39 (1200) |

| White | 14 (61) | 86 (484) | 35 (545) |

| Black | 22 (35) | 78 (176) | 11 (211) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, other | 21 (29) | 79 (145) | 15 (174) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 31 (312) | 69 (590) | 51 (902) |

| Female | 23 (375) | 77 (853) | 49 (1228) |

| Educational attainment | |||

| < High school | 50 (394) | 50 (334) | 22 (728) |

| High school graduate | 29 (151) | 71 (334) | 23 (485) |

| Some college | 21 (103) | 79 (420) | 32 (523) |

| College graduate or postgraduate | 11 (39) | 89 (355) | 23 (394) |

| Age, y | |||

| < 24 | 33 (124) | 67 (182) | 18 (306) |

| 25–44 | 31 (461) | 69 (872) | 51 (1333) |

| 45–64 | 17 (102) | 83 (389) | 32 (491) |

| Median family income,b $ (number of families) | 13 200 (687) | 35 000 (1443) | 26 700 (2130) |

| Median family nonhousing assets, $ (number of families) | 1500 (687) | 12 000 (1443) | 6000 (2130) |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 38 (306) | 62 (394) | 35 (700) |

| Married | 19 (316) | 81 (865) | 53 (1181) |

| Divorced or widowed | 29 (65) | 71 (184) | 13 (249) |

| Child aged 0–2 y in household | |||

| Yes | 29 (153) | 71 (288) | 12 (441) |

| No | 27 (534) | 73 (1155) | 88 (1689) |

| Child aged 3–12 y in household | |||

| Yes | 27 (329) | 73 (669) | 27 (998) |

| No | 27 (358) | 73 (774) | 73 (1132) |

| Child aged 13–17 y in household | |||

| Yes | 19 (112) | 81 (354) | 14 (466) |

| No | 28 (575) | 72 (1089) | 86 (1664) |

| Pregnant | |||

| Yes | 15 (2) | 85 (16) | 1 (18) |

| No | 27 (685) | 73 (1427) | 100 (2112) |

| New child born after start of 2-year interval | |||

| Yes | 28 (103) | 72 (208) | 9 (311) |

| No | 27 (584) | 73 (1235) | 91 (1819) |

| Receiving public assistance | |||

| Yes | 18 (78) | 82 (196) | 8 (274) |

| No | 28 (609) | 72 (1247) | 92 (1856) |

| Employment status | |||

| Not employed | 37 (241) | 63 (350) | 24 (591) |

| Working part time | 27 (88) | 73 (173) | 13 (261) |

| Working full time in low status occupation | 30 (280) | 70 (446) | 33 (726) |

| Working full time in high status occupation | 16 (78) | 84 (474) | 31 (552) |

| No. of months in current insurance period | |||

| 0–12 | 41 (101) | 59 (118) | 10 (219) |

| 13–24 | 50 (148) | 50 (118) | 10 (266) |

| 25–36 | 40 (134) | 60 (195) | 15 (329) |

| 37–48 | 9 (30) | 91 (140) | 8 (170) |

| 49–60 | 29 (29) | 71 (88) | 7 (117) |

| 61–120 | 24 (100) | 76 (325) | 18 (425) |

| 121–240 | 20 (114) | 80 (307) | 20 (421) |

| ≥241 | 7 (31) | 93 (152) | 12 (183) |

aUnweighted ns and weighted percentages are reported. Percentages in Total column may not add to 100 because of rounding.

bFamily income is total family income from all sources except income from assets. Family assets represent the dollar value of all nonhousing assets. Twenty-four percent of the sample reported $0 in family income, and 30% of the sample reported $0 in nonhousing assets. These cases were included in the calculation of median income and nonhousing assets.

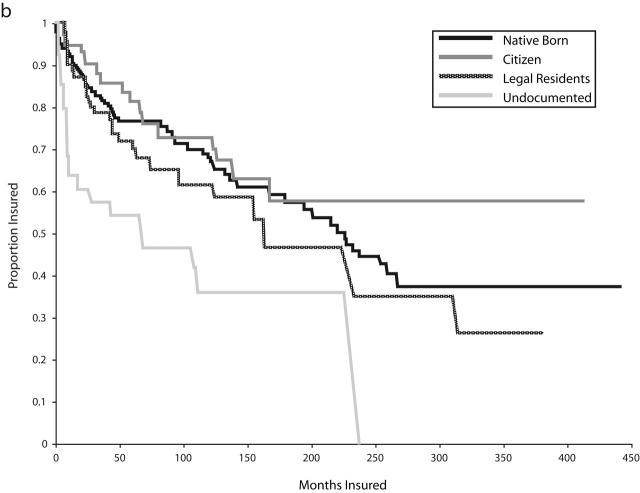

FIGURE 1—

Survivor functions among adults aged 18–64 years predicting a transition from (a) uninsurance to insurance (n = 723) and (b) insurance to uninsurance (n = 1398): Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey, 2000–2001.

Note. Only the first observed health insurance periods were included. Periods were censored at 450 months, resulting in the exclusion of 5 people from the population analyzed in 1(a) and 4 people from that analyzed in 1(b).

Figure 1b ▶ presents the survival curve for immigrants and nonimmigrants who were insured at the beginning of observation. Figure 1 ▶ shows that, among immigrants of all statuses, keeping insurance was easier than initially obtaining it. Among respondents who were insured at the start of the period, 93% of native-born participants remained insured throughout the 2-year period compared with 90% of naturalized citizens and undocumented immigrants and 89% of legal residents. As seen in Figure 1b ▶, the undocumented and legal residents had shorter insured periods, indicating that they had a harder time keeping their coverage. More than 50% of the undocumented immigrants and legal residents had lost their coverage, by 69 months and 164 months, respectively. However, more than 50% of native-born and of naturalized citizens remained insured for more than 200 months.

Characteristics of the Uninsured and Immigrant Populations

Are disparities in coverage by immigrant status caused by socioeconomic and demographic differences between immigrants and nonimmigrants? Table 1 ▶ shows the characteristics of insured and uninsured respondents at interview. The results are consistent with previous research: ethnic minorities; men; respondents with lower education, lower levels of family income, and nonhousing assets; young and never-married respondents; individuals not employed; part-time workers; and respondents in lower-status occupations were less likely to be insured. Table 1 ▶ also shows that coverage varied greatly among immigrants by legal status. Undocumented immigrants were only half as likely as legal residents to be insured. Naturalized citizens were more likely to be insured than were other immigrants but were not as likely to be insured as were native–born citizens. Table 2 ▶ displays the characteristics of immigrants by status group. Immigrants were more likely to have characteristics related to being uninsured, including being male, young, and single; having lower education, income, and nonhousing assets; and working in lower-status jobs. Immigrant status groups also differed considerably from each other. Undocumented immigrants and legal residents were more likely than naturalized and native-born citizens to have the characteristics associated with being uninsured.

TABLE 2—

Characteristics of Adults Aged 18–64 Years by Citizenship Status at Interview: Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey, 2000–2001 (n = 2130)

| Citizenship Status | |||||

| Undocumented Immigrants, % (No.)a | Legal Residents, % (No.) | Naturalized Citizens, % (No.) | US Native-Born Citizens, % (No.) | Total % (No.) | |

| Language of interview | |||||

| English | 5 (15) | 49 (143) | 79 (210) | 97 (958) | 76 (1326) |

| Spanish | 95 (362) | 51 (310) | 21 (105) | 3 (27) | 24 (804) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Latino | 98 (369) | 67 (373) | 37 (173) | 20 (285) | 39 (1200) |

| White | 1 (4) | 9 (33) | 15 (56) | 55 (452) | 35 (545) |

| Black | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | 3 (5) | 17 (199) | 11 (211) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, other | 2 (4) | 22 (40) | 46 (81) | 8 (49) | 15 (174) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 59 (170) | 55 (202) | 44 (130) | 50 (400) | 51 (902) |

| Female | 41 (207) | 45 (251) | 56 (185) | 50 (585) | 49 (1228) |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| > High school | 66 (271) | 40 (250) | 19 (84) | 9 (123) | 22 (728) |

| High school graduate | 25 (83) | 22 (97) | 19 (64) | 25 (241) | 23 (485) |

| Some college | 5 (14) | 22 (56) | 34 (82) | 39 (371) | 32 (523) |

| College graduate or postgraduate | 3 (9) | 16 (50) | 28 (85) | 27 (250) | 23 (394) |

| Age, y | |||||

| < 24 | 25 (74) | 16 (46) | 5 (12) | 20 (174) | 18 (306) |

| 25–44 | 69 (284) | 59 (315) | 46 (182) | 46 (552) | 51 (1333) |

| 45–64 | 6 (19) | 25 (92) | 50 (121) | 34 (259) | 32 (491) |

| Median family income,b | 12 000 (377) | 23 000 (453) | 36 000 (315) | 34 030 (985) | 26 700 (2130) |

| $ (number of families) | |||||

| Median family nonhousing assets, | 0 (377) | 4000 (453) | 14 000 (315) | 12,000 (985) | 6000 (2130) |

| $ (number of families) | |||||

| Marital status | |||||

| Never married | 52 (179) | 34 (132) | 16 (52) | 37 (337) | 35 (700) |

| Married | 42 (178) | 60 (287) | 71 (223) | 47 (493) | 53 (1181) |

| Divorced or widowed | 6 (20) | 7 (34) | 13 (40) | 16 (155) | 13 (249) |

| Child aged 0–2 y in household | |||||

| Yes | 22 (111) | 15 (103) | 10 (49) | 11 (178) | 12 (441) |

| No | 78 (266) | 85 (350) | 90 (266) | 89 (807) | 88 (1689) |

| Child aged 3–12 y in household | |||||

| Yes | 37 (214) | 34 (237) | 33 (154) | 22 (393) | 27 (998) |

| No | 63 (163) | 66 (216) | 67 (161) | 78 (592) | 73 (1132) |

| Child aged 13–17 y in household | |||||

| Yes | 10 (56) | 16 (106) | 28 (109) | 11 (195) | 14 (466) |

| No | 90 (321) | 84 (347) | 72 (206) | 89 (790) | 86 (1664) |

| Pregnant | |||||

| Yes | 1 (7) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 1 (18) |

| No | 99 (370) | 99 (448) | 99 (313) | 100 (981) | 100 (2112) |

| New child born after start of 2-year interval | |||||

| Yes | 16 (81) | 12 (76) | 8 (33) | 7 (121) | 9 (311) |

| No | 84 (296) | 88 (377) | 92 (282) | 93 (864) | 91 (1819) |

| Receiving public assistance | |||||

| Yes | 7 (58) | 5 (53) | 5 (29) | 10 (134) | 8 (274) |

| No | 93 (319) | 95 (400) | 95 (286) | 90 (851) | 92 (1856) |

| Employment status | |||||

| Not employed | 25 (134) | 28 (151) | 21 (68) | 23 (238) | 24 (591) |

| Working part-time | 8 (27) | 14 (61) | 9 (38) | 14 (135) | 13 (261) |

| Working full-time in low-status occupation | 63 (200) | 40 (189) | 39 (113) | 23 (224) | 33 (726) |

| Working full-time in high-status occupation | 4 (16) | 18 (52) | 31 (96) | 39 (388) | 31 (552) |

| No. of months in current insurance period | |||||

| 0–12 | 17 (53) | 13 (56) | 7 (23) | 8 (87) | 10 (219) |

| 13–24 | 19 (79) | 10 (64) | 9 (30) | 8 (93) | 10 (266) |

| 25–36 | 24 (76) | 14 (71) | 14 (45) | 14 (137) | 15 (329) |

| 37–48 | 5 (22) | 11 (33) | 7 (23) | 9 (92) | 8 (170) |

| 49–60 | 6 (19) | 7 (25) | 6 (18) | 8 (55) | 7 (117) |

| 61–120 | 14 (64) | 19 (95) | 26 (75) | 17 (191) | 18 (425) |

| 121–240 | 15 (56) | 23 (86) | 23 (73) | 19 (206) | 20 (421) |

| ≥241 | 1 (8) | 4 (23) | 9 (28) | 18 (124) | 12 (183) |

aUnweighted ns and weighted percentages are reported. Percentages in Total column may not add up to 100 because of rounding.

bFamily income is total family income from all sources except income from assets. Family assets represent the dollar value of all nonhousing assets. Twenty-four percent of the sample reported $0 in family income, and 30% of the sample reported $0 in nonhousing assets. These cases were included in the calculation of median income and nonhousing assets.

Obtaining Insurance Coverage

Table 3 ▶ presents unadjusted and adjusted relative risks. The unadjusted results show the relative risk that an uninsured individual will become insured with no control for socioeconomic status variables. A multivariate logistic regression was used to generate relative risks adjusted for characteristics listed in Table 1 ▶. Table 3 ▶ contains unadjusted relative risks for immigration status and adjusted relative risks for immigrant status and selected time-varying independent variables shown to affect health insurance eligibility in past research (e.g., employment status, pregnancy). The unadjusted relative risks show that undocumented immigrants and legal residents who are uninsured were significantly less likely than native-born citizens to become insured. The adjusted results show that undocumented immigrants and legal residents remained significantly less likely to gain insurance, even when other covariates affecting health insurance eligibility were held constant, although the effects were smaller in magnitude. Legal residents had lower odds (P < .10) of gaining insurance. Compared with native-born Americans, undocumented immigrants had a 71% lower relative risk of gaining insurance, and legal residents had a 40% lower relative risk of gaining insurance.

TABLE 3—

Unadjusted and Adjusted Relative Risks of Models Predicting Uninsured-to-Insured Transition and Insured-to-Uninsured Transition for Adults Aged 18–64 Years: Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey, 2000–2001 (n = 2418)

| Unadjusted Uninsured-to-Insured Transition (n = 848), RR (95% CI) | Adjusted Uninsured-to-Insured Transition (n = 848), ARR (95% CI) | Unadjusted Insured-to-Uninsured Transition (n = 1570), RR (95% CI) | Adjusted Insured-to-Uninsured Transition (n = 1570), ARR (95% CI) | |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Immigration status (reference = native born) | ||||

| Undocumented immigrants | 0.22 (0.11, 0.45) | 0.29 (0.14, 0.61) | 3.22 (2.00, 5.16) | 2.17 (1.07, 4.39) |

| Legal residents | 0.44 (0.26, 0.76) | 0.60 (0.34, 1.05) | 1.86 (0.97, 3.57) | 1.67 (0.85, 3.29) |

| Naturalized citizens | 0.73 (0.38, 1.39) | 0.92 (0.42, 2.03) | 1.42 0.80, 2.50) | 1.22 (0.69, 2.17) |

| Time-varying covariates | ||||

| Has child aged 0–2 y in household (reference = no child aged 0–2 y in household) | 0.73 (0.41, 1.31) | 1.37 (0.68, 2.79) | ||

| Has child aged 3–12 y in household (reference = no child aged 3–12 y in household) | 0.43 (0.24, 0.80 | 0.97 (0.57, 1.63) | ||

| Has child aged 13–17 y in household (reference = no child aged 13–17 y in household) | 1.01 (0.54, 1.90) | 1.15 (0.65, 2.04) | ||

| Pregnant (reference = not pregnant) | 7.93 (4.36, 14.42) | 0.96 (0.51, 1.82) | ||

| New child born after start of 2-year interval (reference = no new child born after 2-year interval start date) | 0.53 (0.24 1.16) | 2.65 (1.41, 4.97) | ||

| Received public assistance (reference = did not receive public assistance) | 1.64 (0.90, 2.97) | 0.59 (0.29, 1.21) | ||

| Employment status (reference = not employed) | ||||

| Working part time | 0.84 (0.48, 1.46) | 0.79 (0.41, 1.52) | ||

| Working full time in low-status occupation | 0.90 (0.60, 1.36) | 0.73 (0.39, 1.37) | ||

| Working full time in high-status occupation | 1.39 (0.71, 2.74) | 0.89 (0.51, 1.56) | ||

Note. RR = relative risk; ARR = adjusted relative risk; CI = confidence interval. Models were multivariate logit models. Taking the interview in English, gender, race/ethnicity, education, age, marital status, log of family income, reporting $0 for family income, log of nonhousing assets, reporting $0 for nonhousing assets, and length of time spent in current insurance periods were also controlled in models. Results are representative for Los Angeles County; differential probabilities of selection and response were controlled by the inclusion of variables important in sampling eligibility and nonresponse directly in the model. These variables included households with children, census tract of residence, respondent type, gender, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and interactions between variables.

Family structure also significantly affected the relative risk of becoming insured. The relative risk of obtaining insurance was increased more than 7 times for pregnant women compared with men and nonpregnant women. Respondents with children aged 3–12 years were significantly less likely to gain insurance than were respondents who did not have children aged 3–12 years. In contrast to previous research findings, current employment status did not significantly affect the relative risk of gaining insurance.18 Lagged employment variables indicating whether a respondent worked full-time, worked part-time, or was not employed during the preceding 1, 3, or 6 months were included in the models to control for the possibility of delay between beginning a new job and obtaining insurance. The coefficients were not significant (results not shown), and these variables were not included in the model.

Losing Insurance Coverage

The second 2 columns in Table 3 ▶ show the unadjusted and adjusted relative risks of losing insurance coverage for those who are insured. The unadjusted relative risks show that undocumented immigrants were significantly more likely to lose insurance than were native-born citizens. Legal residents were more likely to lose insurance (P < .10) than were native-born citizens. After adjustment for other insurance eligibility covariates and socioeconomic status, only undocumented immigrants had a significantly higher relative risk (2.17) of losing insurance. Legal residents and naturalized citizens did not significantly differ from native-born citizens in their relative risks of losing insurance. Respondents who had a new child during the EHC had a significantly higher relative risk (2.7) of losing insurance compared with respondents who did not have a new child during the EHC.

DISCUSSION

Our study examined the process of obtaining and losing health insurance coverage for immigrants and native-born Americans in Los Angeles County. As in previous studies, we found that immigrants are much less likely to be insured at any point in time compared with the native-born population.7,8,10 In contrast to most previous studies,7,10,12 however, the LAFANS-1 data allowed us to distinguish among immigrant groups on the basis of legal status. Our results show that the process of gaining and losing insurance differs substantially between immigrant groups. Undocumented immigrants have the highest uninsured rates (Table 1 ▶) and are most disadvantaged in socioeconomic terms (Table 2 ▶). They have much more difficulty obtaining and keeping insurance, even after adjustment for other factors affecting insurance eligibility (Table 3 ▶).

The significant effect of undocumented immigrant status, even after control for socioeconomic status, on gaining and losing insurance has important implications for research and policy. Most national surveys do not routinely collect information on legal status.9,10 Our results suggest that this information is essential, because the dynamics of health insurance coverage differ substantially on the basis of legal status. Future research should also examine the relative importance of ineligibility for public insurance, type of employment, and other factors (e.g., fear of providing personal information necessary to obtain insurance) as causes of high uninsurance rates for undocumented immigrants.

Legal residents may also be less likely than native-born citizens to gain health insurance, although our findings were only significant at P < .10 when other covariates affecting health insurance eligibility were held constant. The gap between legal residents and other groups is likely to be considerably smaller in Los Angeles than in the rest of the nation, because California continued to fund Medicaid benefits to legal residents arriving after the enactment of the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.16,17 Legal residents may avoid using public insurance for fear that it will be used against them in future citizenship applications.11,27 Thus, although legal residents are eligible for public and employer-based coverage, they may decide not to apply.

However, legal residents are not more likely than native-born citizens to lose insurance. For legal residents, future research and public policy should focus on initial barriers to gaining insurance. Similarly, research should further examine how the process of gaining and retaining insurance might differ for legal residents compared with undocumented immigrants.

Our results also indicate that naturalized citizens are less likely to have insurance because they have characteristics that decrease their eligibility for insurance versus native-born citizens. After adjustment for socioeconomic status, naturalized citizens are not statistically significantly different from native-born citizens in their ability to gain or maintain insurance (Table 3 ▶). This finding reinforces the argument that naturalized citizens’ lack of insurance is largely a result of their disadvantaged employment and socioeconomic position.7,8,14 Therefore, policies that focus on extending insurance coverage to the working poor will increase insurance rates among naturalized citizens.

Finally, our results illustrate the importance of moving beyond cross-sectional analyses to examine the process of obtaining and losing insurance. As our results for immigrant subgroups show, these 2 processes may differ in ways that lead to different policy prescriptions. We also found that once people have maintained insurance for a year or more, they are significantly less likely to lose insurance (results not shown). Analyses of transitions into and out of health insurance programs are particularly critical for vulnerable groups, such as undocumented immigrants and low-income people, because continuity of coverage is likely to have important effects on access to primary care by disrupting an ongoing relationship with the provider. For example, the Commonwealth 2001 Health Insurance Survey found that 31% of respondents with a recent period of uninsurance did not report a regular source of care, compared with 16% of respondents who were insured all year.6 A better understanding of populations that move frequently into and out of health insurance programs or that often change insurance types (i.e. moving from Medicaid to employer-based coverage) would help us identify groups at risk of compromised access.

Acknowledgments

Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (LAFANS-1) was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health/Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, Department of Health and Human Services/Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, and the Los Angeles County Urban Research Group.

We gratefully acknowledge the LAFANS-1 research group at the University of California, Los Angeles, especially Robert Mare, and 3 anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Human Participant Protection The data are publicly available at http://www.lasurvey.rand.org, contain no personal identifiers, and are exempt from human subjects approval protocol. An exemption was obtained by the institutional review board of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Contributors J. C. Prentice and A. R. Pebley originated the study and interpreted findings. J. C. Prentice conducted analyses and wrote initial drafts of the article. A. R. Pebley supervised analyses, synthesized results, and revised drafts of the article. N. Sastry provided statistical help to accurately control for the survey design in analyses.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Kasper JD, Giovannini TA, Hoffman C. Gaining and losing health insurance: strengthening the evidence for effects on access to care and health outcomes. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:298–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudano JJJr, Baker DW. Intermittent lack of health insurance coverage and use of preventive services. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284: 2061–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoen C, DesRoches C. Uninsured and unstably insured: the importance of continuous insurance coverage. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:186–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman C, Schoen C, Rowland D, Davis K. Gaps in health coverage among working-age Americans and the consequences. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2001;12:272–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duchon L, Schoen C, Doty MM, Davis K, Strumpf E, Bruegman S. Security Matters: How Instability in Health Insurance Puts US Workers At Risk. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2001.

- 7.Brown ER, Ponce N, Rice T, Lavarreda SA. The State of Health Insurance in California: Findings From the 2001 California Health Interview Survey. Los Angeles, Calif: University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research; 2002.

- 8.Thamer M, Richard C, Casebeer AW, Ray NF. Health insurance coverage among foreign-born US residents: the impact of race, ethnicity and length of residence. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown ER, Ponce N, Rice T. The State of Health Insurance in California: Recent Trends, Future Prospects. Los Angeles, Calif: University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research; 2001.

- 10.Carrasquillo O, Carrasquillo AI, Shea S. Health insurance coverage of immigrants living in the United States: differences by citizenship status and country of origin. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:917–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ku L, Frelich A. Caring for Immigrants: Health Care Safety Nets in Los Angeles, New York, Miami, and Houston. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2001.

- 12.Ku L, Matani S. Left out: immigrants’ access to health care and insurance. Health Aff. 2001;20: 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glied SA. Challenges and option for increasing the number of Americans with health insurance. Inquiry. 2001;38:90–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angel RJ, Angel JL, Markides KS. Stability and change in health insurance among older Mexican Americans: longitudinal evidence from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1264–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown ER, Wyn R, Yu H, Valenzuela A, Dong L. Access to health insurance and health care for immigrant children. In: Hernandez D, ed. Children of Immigrants: Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999:126–186.

- 16.Ellwood MR, Ku L. Welfare and immigration reforms: unintended side effects for Medicaid. Health Aff. 1998;17:137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fix M, Passel J. The Scope and Impact of Welfare Reform’s Immigrant Provisions. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2002.

- 18.Swartz K, Marcotte J, McBride TD. Personal characteristics and spells without health insurance. Inquiry. 1993;30:64–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBride TD. Uninsured spells of the poor: prevalence and duration. Health Care Financ Rev. 1997;19: 145–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sastry N, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Adams J, Pebley AR. The Design of a Multilevel Longitudinal Survey of Children, Families, and Communities: The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey. Santa Monica, Calif: RAND; 2003. Available at: http://www.lasurvey.rand.org/publications.htm. Accessed September 2003.

- 21.Pebley AR, Sastry N. The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey: Household Questionnaires. Santa Monica, Calif: RAND; 2003. Available at: http://www.lasurvey.rand.org/publications.htm. Accessed September 2003.

- 22.Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1995.

- 23.Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services. 2002. Available at: http://www.ladpss.org/dpss/health_care/default.cfm. Accessed December 2002.

- 24.Namboodiri K, Suchindran CM. Life Table Techniques and Their Application. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1997.

- 25.Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0 [computer program]. College Station, Tex: Stata Corp; 2001.

- 26.Sastry N, Pebley AR. Non-Response in the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey. Santa Monica, Calif: RAND; 2003. Available at: http://www.lasurvey.rand.org/publications.htm. Accessed September 2003.

- 27.Hagan J, Rodriguez N, Capps R, Kabiri N. The effects of recent welfare and immigration reforms on immigrants’ access to health care. Int Migration Rev. 2003;37:444–463. [Google Scholar]