Abstract

Vinyl and diene derivatives of thiolactomycin have been prepared via Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination from protected 5-formyl-3,5-dimethylthiotetronic acid. Several 4-position protecting groups and a variety of phosphonates were evaluated, with MOM protection and β-ketophosphonates yielding the highest ratio of desired product to deformylated product.

Keywords: thiolactomycin, olefination, deformylation

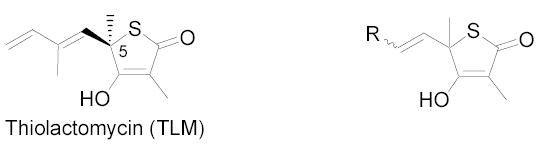

Thiolactomycin (TLM, Figure 1) is an antibacterial natural product with broad-spectrum activity originally isolated from a species of Nocardia.1 The thiotetronic acid core structure and 5-position isoprene side chain of TLM are found in several other natural products including thiotetromycin, U68204, and 834-B1.2 Thiotetronic acids inhibit fatty acid biosynthesis in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes and may have multiple therapeutic applications.2,3i Thus, significant synthetic efforts have been directed at TLM and its derivatives.3 The antibiotic activity of TLM is the result of inhibition of important fatty acid biosynthetic enzymes, the β-ketoacyl ACP synthases.4 These enzymes catalyze a Claisen condensation between malonyl-ACP and an acyl-CoA or acyl-ACP primer, elongating the growing fatty acyl chain by two carbon atoms. We have explored the SAR of the 5-position of TLM against condensing enzymes from both Escherichia coli (FabB) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (KasA/B) and found that the double bonds of the TLM isoprene side chain play a critical role in determining the biological activity of this molecule.3k We therefore sought a facile synthetic route to diverse 5-vinyl derivatives of TLM.

Figure 1.

Structures of thiolactomycin and vinyl derivatives of 3,5-dimethylthiotetronic acid.

Previous methods of preparing 5-vinyl derivatives of TLM relied upon formation of the thiotetronic acid ring after generation of one or both double bonds of the isoprenoid chain.3e,3i,5 These linear routes offer limited potential for synthesis of large numbers of 5-vinyl TLM derivatives. Wang and Salvino prepared a 5-methacrolein derivative from 1 via a tandem aldol-type reaction followed by dehydration.3a This strategy led to the synthesis of racemic TLM but was very low yielding and allowed for only limited diversity. We have focused on the discovery of novel synthetic routes for TLM derivatives that conserve the double bond closest to the thiolactone ring with the opportunity for preparation of small libraries of related compounds (Figure 1). Herein, we report new routes to 5-vinyl and 5-diene derivatives of TLM starting from 3,5-dimethylthiotetronic acid (1).

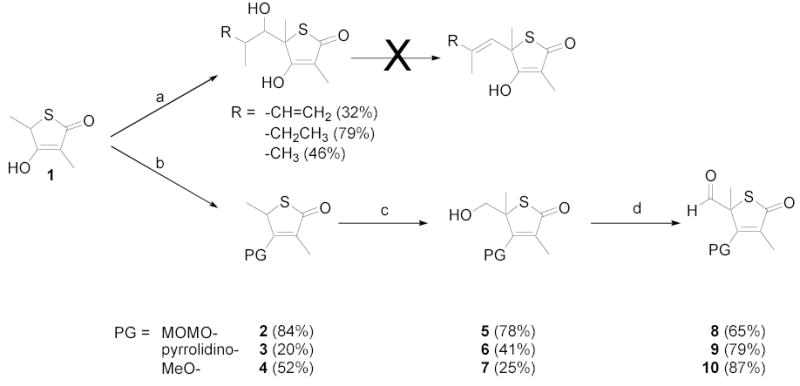

Initially, we attempted to generate 5-vinyl derivatives using an aldol-type reaction of 13a with a variety of aldehydes, followed by dehydration (Scheme 1). The dianion of 1, generated with LiHMDS, was reacted with selected aldehydes to obtain secondary alcohols at the 5-position in moderate to good yield. However, attempted dehydration of the resulting alcohols under a variety of conditions failed to give the corresponding 5-vinyl products. Instead, only the retroaldol-type reaction was observed, regenerating starting material 1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of protected aldehydes of 3,5-dimethylthiotetronic acid. Reagents and conditions: (a) LiHMDS (2.2 eq), RCH(CH3)CHO; (b) 2: MOMCl, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, rt, 2 h; 3: pyrrolidine, toluene, reflux, overnight; 4: i) nBu4NOH (aq), rt, 1 h; ii) Me2SO4, CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h; (c) i) LiHMDS (1.1 eq), THF, 0 °C, 30 min; ii) paraformaldehyde, 0 °C → rt, 1 h; (d) Dess-Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h.

These results led us to prepare 5-formyl derivatives envisioning an olefination strategy that did not rely upon this problematic dehydration (Scheme 1). Neither direct formylation of 1 nor oxidation of the corresponding 5-hydroxymethyl compound were successful (not shown).3k Oxidation of primary alcohols at the 5-position of tetronic or thiotetronic acids has been previously reported to have been unsuccessful without first protecting the hydroxyl group at the 4-position.3b,6 We explored three strategies for protecting the hydroxyl group of 1. MOMCl and DIPEA were used to obtain 2,3k,7 pyrrolidine under reflux to obtain 3,8 and Me2SO4 with nBu4NOH to obtain 4.3g,6 Hydroxymethylation of 2–4 using LiHMDS and paraformaldehyde successfully generated 5–7.8b Oxidation of 5–7 with Dess-Martin periodinane gave protected aldehydes 8–10.9

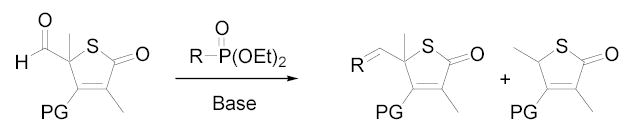

A variety of reaction conditions using aldehydes 8–10 were explored to generate the 5-position double bond. Simple Wittig10 and Tebbe11 reactions with 8 failed to give 5-vinyl products, and olefination attempts from 8 using phosphoranylidenes also did not afford the desired compounds, despite literature precedent for the latter reaction from the corresponding tetronic acid.6 Treatment of compound 8 or 10 with simple alkylphosphonates and nBuLi/HMPA, failed to produce the desired products (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). Similar results were found using α-branched alkylphosphonates (not shown). The only products resulting from the above reactions were the deformylated products 2 and 4.

Table 1.

Products and yields from HWE reactions: Olefination versus deformylation.

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

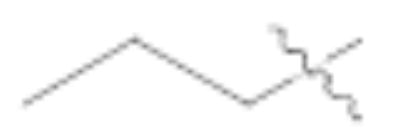

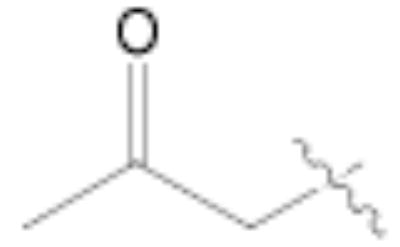

| Entry | R | Aldehyde (PG) | Base | Desired Product (% yield) | Deformylation Product (% yield) |

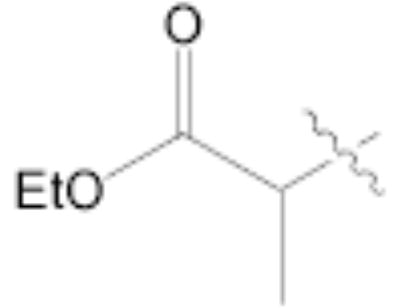

| 1 |

|

8 (MOMO-) | nBuLi/HMPA | -- | 2 (only product) |

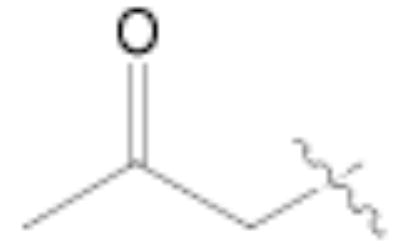

| 2 |

|

10 (CH3O-) | nBuLi/HMPA | -- | 4 (only product) |

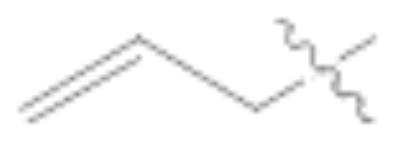

| 3 |

|

8 (MOMO-) | nBuLi/HMPA | -- | 2 (only product) |

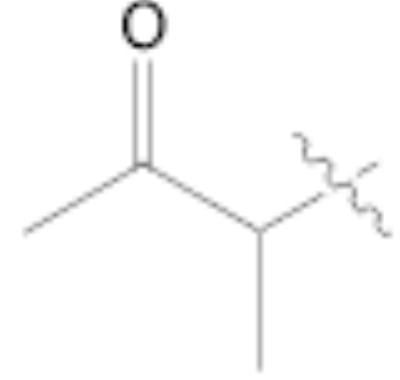

| 4 |

|

9 (pyrrolidino-) | nBuLi/HMPA | 11 (31%) | 3 (45%) |

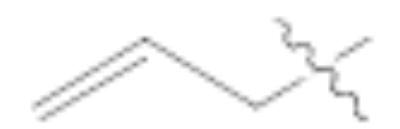

| 5 |

|

9 (pyrrolidino-) | nBuLi/HMPA | 12 (4%) | 3 (46%) |

| 6 |

|

9 (pyrrolidino-) | DIPEA/LiCl | 13 (19%) | 3 (10%) |

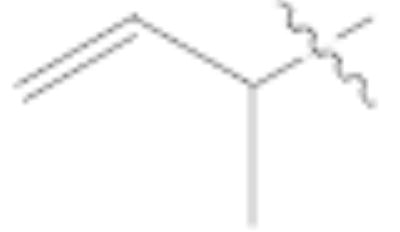

| 7 |

|

8 (MOMO-) | DIPEA/LiCl | 14 (48%) | 2 (18%) |

| 8 |

|

8 (MOMO-) | DIPEA/LiCl | -- | 2 (only product) |

| 9 |

|

8 (MOMO-) | DIPEA/LiCl | 15 (30%) | 2 (21%) |

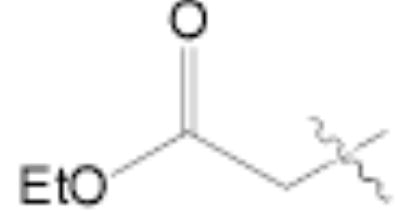

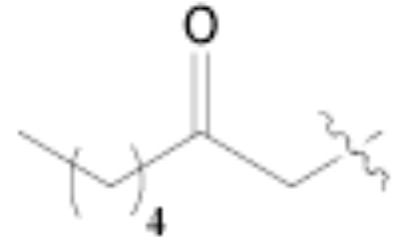

| 10 |

|

8 (MOMO-) | DIPEA/LiCl | -- | 2 (only product) |

| 11a |

|

8 (MOMO-) | DIPEA/LiCl | 16 (48%) | 2 (12%) |

Dimethyl (2-oxoheptyl)phosphonate was used.

Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons (HWE) reactions using allylphosphonates were successful in generating the desired olefins but only in the case of pyrrolidine-protected aldehyde 9 (Table 1, entries 4 and 5).12 Using diethyl allylphosphonate, trans-diene 1113 was formed in 31% yield whereas the deformylated product 3 was formed in 45% yield (entry 4). The yield for the reaction with the corresponding α-methyl phosphonate was dramatically lower (4%, entry 5), and the deformylated product 3 was the major product. Likewise, aldehydes 8 and 10 yielded only the undesired deformylated product (entry 3 and others not shown).

Both MOM- and pyrrolidino-protected aldehydes 8 and 9 gave the desired olefins with trans geometry using stabilized β-ketophosphonates and DIPEA/LiCl (Table 1, entries 6, 7, 9, and 1114). Unexpectedly, these products were the major ones formed in these reactions. The best results were obtained using MOM-protected aldehyde 8 with either diethyl (2-oxopropyl)phosphonate to give conjugated ketone 14 or dimethyl (2-oxoheptyl)phosphonate to give 16. α-Branched-β-ketophosphonates15, unfortunately, yielded only deformylation product 2 when reacted with aldehyde 8 (entries 8 and 10).

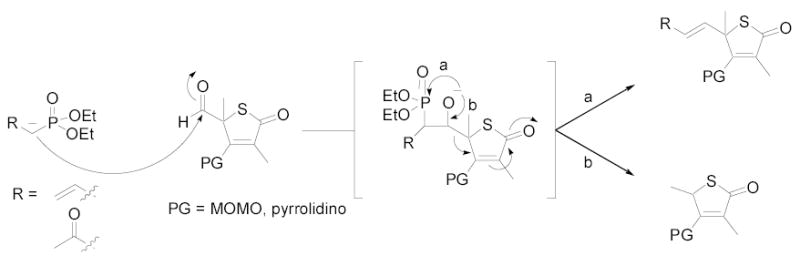

The observation that olefination preferentially occurred using stabilized phosphonates led us to propose a mechanism for deformylation (Figure 2). Production of the β-alkoxyphosphonate intermediate can result in two potential outcomes: formation of an oxygen-phosphorus bond leading to the desired olefin product (path a), or regeneration of the carbonyl bond giving rise to a retro-aldol type reaction (path b). The latter pathway would be predicted to result in the release of an α-formylphosphonate and protected-3,5-dimethylthiotetronic acid. In the case of diethyl allylphosphonate, molecular ions for 3 and α-formylallylphosphonate were detected by LC/MS, and compound 3 was confirmed by NMR. For either phosphonate, we would expect generation of the aromatic thiophenoxide anion to contribute to the driving force for this side reaction.16 Alternatively, allylic migration of the diethyl allylphosphonate anion would also lead to the deformylated product.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism for olefination versus deformylation.

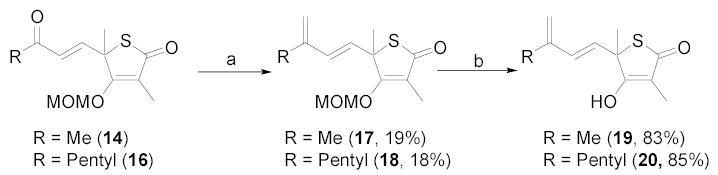

To demonstrate the utility of this chemistry in generating derivatives of TLM with a diene at the 5-position, we investigated the possibility of methylenation of HWE product 14. Wittig and Tebbe reaction conditions gave the desired products, while Nysted17 and Peterson18 methylenations did not. The Wittig reaction condition afforded a slightly lower yield than the Tebbe condition to generate compound 17. The Tebbe reaction condition also gave the desired product 1819 from conjugated ketone 16. Conjugated ester 15 did not generate the diene product under the Tebbe reagent condition. MOM-deprotection of diene compounds 17 and 18 was accomplished using polymer-bound TsOH and silica gel in MeOH3k to afford diene compounds 19 and 20.20

In summary, 5-vinyl derivatives of TLM were prepared via HWE olefination of MOM- and pyrrolidino-protected aldehydes (8 and 9) with stabilized phosphonates. Due to the pro-aromatic nature of these aldehydes, deformylation was always observed as the major competing side reaction. Deformylation was minimized using β-ketophosphonates in the presence of a mild base. 5-Position dienes were synthesized via methylenation of conjugated ketones, demonstrating the utility of this method in generating novel thiotetronic acid analogs.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Terminal double bond synthesis of TLM diene derivatives. Reagents and conditions: (a) Tebbe reagent, THF, −10 ºC → 0 ºC, 3h; (b) silica gel, polymer-bound TsOH, MeOH, rt, overnight.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Lloyd of NIDDK (NIH) for HRMS analysis. This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of NIAID, NIH.

References

- 1.a Oishi H, Noto T, Sasaki H, Suzuki K, Hayashi T, Okazaki H, Ando KJ. Antibiotics. 1982:391–395. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sasaki H, Oishi H, Hayashi T, Matsuura I, Ando K, Sawada M. J Antibiotics. 1982:396–400. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Miyakawa S, Suzuki K, Noto T, Harada Y, Okazaki H. J Antibiotics. 1982:411–419. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Omura S, Nakagawa A, Iwata R, Hatano A. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1983;36:1781–1782. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Omura S, Iwai Y, Nakagawa A, Iwata R, Takahashi Y, Shimizu H, Tanaka H. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1983;36:109–114. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dolak LA, Castle TM, Truesdell SE, Sebek OK. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1986;39:26–31. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sato T, Suzuki K, Kadota S, Abe K, Takamura S, Iwanami M. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1989;42:890–896. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Wang CLJ, Salvino JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:5243–5246. [Google Scholar]; b Chambers MS, Thomas EJ. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1997:417–431. [Google Scholar]; c Kremer L, Douglas JD, Baulard AR, Morehouse C, Guy MR, Alland D, Dover LG, Lakey JH, Jacobs WR, Jr, Brennan PJ, Minnikin DE, Besra GS. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16857–16864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sakya SM, Suarez-Contreras M, Dirlam JP, O’Connell TN, Hayashi SF, Santoro SL, Kamicker BJ, George DM, Ziegler CB. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:2751–2754. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e McFadden JM, Frehywot GL, Townsend CA. Org Lett. 2002;4:3859–3862. doi: 10.1021/ol026685k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Senior SJ, Illarionov PA, Gurcha SS, Campbell IB, Schaeffer ML, Minnikin DE, Besra GS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:3685–3688. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Shenoy G, Kim P, Goodwin M, Nguyen QA, Barry CE, III, Dowd CS. Heterocycles. 2004;63:519–527. doi: 10.3987/com-03-9947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Jones SM, Urch JE, Kaiser M, Brun R, Harwood JL, Berry C, Gilbert IH. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5932–5941. doi: 10.1021/jm049067d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i McFadden JM, Medghalchi SM, Thupari JN, Pinn ML, Vadlamudi A, Miller KI, Kuhajda FP, Townsend CA. J Med Chem. 2005;48:946–961. doi: 10.1021/jm049389h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Kamal A, Shaik AA, Sinha R, Yadav JS, Arora SK. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:1927–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Kim P, Zhang YM, Shenoy G, Nguyen QA, Boshoff HI, Manjunatha UH, Goodwin M, Lonsdale J, Price AC, Miller DJ, Duncan K, White SW, Rock CO, Barry CE, III, Dowd CS. J Med Chem. 2006;49:159–171. doi: 10.1021/jm050825p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Slayden RA, Lee RE, Armour JW, Cooper AM, Orme IM, Brennan PJ, Besra GS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2813–2819. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hayashi T, Yamamoto O, Sasaki H, Kawaguchi A, Okazaki H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;115:1108–1113. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(83)80050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Nishida I, Kawaguchi A, Yamada M. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1986;99:1447–1454. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Price AC, Choi KH, Heath RJ, Li Z, White SW, Rock CO. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6551–6559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Chambers MS, Thomas EJ. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1989:23–24. [Google Scholar]; b Chambers MS, Thomas EJ, Williams DJ. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1987:1228–1230. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Still IWJ, Drewery MJ. J Org Chem. 1989;54:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takabe K, Mase N, Nomoto M, Daicho M, Tauchi T, Yoda H. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 2002:500–502. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Stachel HD, Fendl A. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 1988;321:439–440. [Google Scholar]; b Li YJ, Liu ZT, Yang SC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:8011–8013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dess DB, Martin JC. J Org Chem. 1983;48:4155–4156. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurjar MK, Karumudi B, Ramana CV. J Org Chem. 2005;70:9658–9661. doi: 10.1021/jo0516234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tebbe FN, Parshall GW, Reddy GS. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:3611–3613. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Garbaccio RM, Stachel SJ, Baeschlin DK, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10903–10908. doi: 10.1021/ja011364+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Principato B, Maffei M, Siv C, Buono G, Peiffer G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;52:2087–2096. [Google Scholar]; c Nagase T, Kawashima T, Inamoto N. Chem Lett. 1984:1997–2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.5-(Buta-1,3-dienyl)-3,5-dimethyl-4-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)-5H-thiophen-2-one (11): At −78 °C and under an argon atmosphere, 1.6 M nBuLi in hexanes (0.20 mL, 0.32 mmol) was added to a solution of diethyl allylphosphonate (57 mg, 0.32 mmol) in THF (0.5 mL). After stirring for 15 min, a solution of 9 (60 mg, 0.27 mmol) in THF and HMPA (1.3 mL; THF:HMPA = 10:1) was added. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to rt, stirred overnight, quenched with H2O, and extracted with EtOAc (2x). The combined organic layers were dried with MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. Column chromatography using silica gel (EtOAc/hexanes = 1/7) afforded the title compound as a colorless oil (21 mg, 0.084 mmol, 31%) as well as 3 (24 mg, 0.12 mmol, 45%). 11: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.76–1.98 (m, 4H), 1.91 (s, 3H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 3.48–3.74 (m, 4H), 5.09–5.13 (m, 1H), 5.19–5.24 (m, 1H), 5.93 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (dd, J = 15.3, 10.2 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (dt, J = 16.8, 10.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 12.3, 25.1, 25.5, 51.5, 56.5, 106.9, 118.0, 129.6, 135.4, 136.2, 169.9, 193.4; LC/MS: 250.1 (M+H+), 272.0 (M+Na+), 521.2 (2M+Na+).

- 14.3,5-Dimethyl-4-methoxymethoxy-5-((E)-3-oxooct-1-enyl)-5H-thiophen-2-one (16): To a solution of LiCl (120 mg, 2.8 mmol) in CH3CN (4 mL) was added dimethyl (2-oxoheptyl)phosphonate (0.64 mL, 2.6 mmol) and DIPEA (0.40 mL, 2.2 mmol) at rt. To this mixture was added a solution of 8 (399 mg, 1.85 mmol) in CH3CN (4 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at rt, quenched with H2O, and extracted with EtOAc (2x). The combined organic layers were dried with MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. Column chromatography using silica gel (EtOAc/hexanes = 1/20–1/10) afforded the title compound as a colorless oil (276 mg, 0.88 mmol, 48%) as well as 2 (43 mg, 0.23 mmol, 12%). 16: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 0.84 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 1.15–1.35 (m, 4H), 1.56 (quint, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.77 (s, 3H), 1.90 (s, 3H), 2.51 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 3.45 (s, 3H), 5.23 (dd, J = 7.5, 6.3 Hz, 2H), 6.23 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 9.5, 14.0, 22.5, 23.5, 23.7, 31.4, 40.8, 56.1, 57.4, 96.1, 113.7, 129.1, 145.2, 175.3, 194.1, 200.1; HRMS (ESMS) calcd for C16H24O4S [M + H+] 313.1474, found 313.1464.

- 15.a Janecki T, Bodalski R. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:1721–1740. [Google Scholar]; b Zeng Y, Reddy DS, Hirt E, Aube J. Org Lett. 2004;6:4993–4995. doi: 10.1021/ol047809r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Clayden J, Knowles FE, Baldwin IR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2412–2413. doi: 10.1021/ja042415g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For a similar observation, see: Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA, Huang X, Simonsen KB, Koumbis AE, Bigot A.J Am Chem Soc 200412610162–10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Nysted, L. N. U.S. Pat. 3,865,848, 1975.; b Clark JS, Marlin F, Nay B, Wilson C. Org Lett. 2003;5:89–92. doi: 10.1021/ol027265y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Peterson DJ. J Org Chem. 1968;33:780–784. [Google Scholar]; b Freeman-Cook KD, Halcomb RL. J Org Chem. 2000;65:6153–6159. doi: 10.1021/jo000665j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.3,5-Dimethyl-4-methoxymethoxy-5-(3-pentylbuta-1,3-dienyl)-5H-thiophene-2-one (18): At −10 °C and under an argon atmosphere, 0.5 M Tebbe reagent (0.50 mL, 0.25 mmol) in toluene was added to a solution of 16 (68 mg, 0.22 mmol) in THF (5 mL). The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to 0 °C, stirred for 3 h, quenched with 0.3 M NaOH (aq) at 0 °C, and extracted with EtOAc (3x). The combined organic layers were dried with MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. Chromatography on preparative TLC (EtOAc/hexanes = 1/3) afforded the title compound as a slightly yellow oil (12 mg, 0.039 mmol, 18%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 1.26–1.28 (m, 4H), 1.42–1.51 (m, 2H), 1.81 (s, 3H), 1.94 (s, 3H), 2.14–2.19 (m, 2H), 3.49 (s, 3H), 5.00 (s, 1H), 5.03 (s, 1H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 5.75 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.29 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 9.5, 14.2, 22.7, 24.2, 27.9, 31.9, 32.1, 57.2, 57.3, 96.1, 113.5, 116.5, 129.5, 132.8, 145.5, 176.8, 195.6; HRMS (ESMS) calcd for C17H26O3S [M + H+] 311.1681, found 311.1682.

- 20.3,5-Dimethyl-5-(3-pentylbuta-1,3-dienyl)-5H-thiophene-2-one (20): To a solution of 18 (14 mg, 0.044 mmol) in MeOH (2 mL) was added silica gel (58 mg) and polymer-bound TsOH (28 mg, 0.056 mmol). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at rt overnight, then was filtered and concentrated to give the title compound as a slightly yellow oil (10 mg, 0.038 mmol, 85%). 1H NMR (MeOH-d4) δ 0.91 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 1.22–1.56 (m, 6H), 1.70 (s, 3H), 1.79 (s, 3H), 2.21 (td, J = 7.8, 0.9 Hz, 2H), 5.03 (m, 2H), 5.78 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H); HRMS (ESMS) calcd for C15H22O2S [M + H+] 267.1419, found 267.1420.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.