Abstract

Many modified genetic codes are found in specific genomes in which one or more codons have been reassigned to a different amino acid from that in the canonical code. We present a new framework for codon reassignment that incorporates two previously proposed mechanisms (codon disappearance and ambiguous intermediate) and introduces two further mechanisms (unassigned codon and compensatory change). Our theory is based on the observation that reassignment involves a gain and a loss. The loss could be the deletion or loss of function of a tRNA or release factor. The gain could be the gain of a new type of tRNA or the gain of function of an existing tRNA due to mutation or base modification. The four mechanisms are distinguished by whether the codon disappears from the genome during the reassignment and by the order of the gain and loss events. We present simulations of the gain-loss model showing that all four mechanisms can occur within the same framework as the parameters are varied. We investigate the way the frequencies of the mechanisms are influenced by selection strengths, the number of codons undergoing reassignment, directional mutation pressure, and selection for reduced genome size.

THE genetic code is a mapping between the 64 possible codons in mRNAs and the 20 amino acids. The canonical genetic code was established before the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). It was initially believed to be universal; however, many deviations from the canonical code have now been discovered in specific groups of organisms and organelles (Knight et al. 2001a). Changes involve the reassignment of a codon or a group of associated codons from one amino acid to another, or from a stop codon to an amino acid, or vice versa. Reassignments are caused by changes in tRNAs or release factors (RF). In many cases, the molecular details are known, but the mechanism by which the changes were fixed in the population is more puzzling. If the translation apparatus changes so that a codon is reassigned to a new amino acid, this will introduce an amino acid change in every protein where this codon occurs. We would expect this to be a selective disadvantage to the organism, and hence selection should act to prevent the change in the code spreading through the population. The situation seems even worse for stop codons, where a change would lead either to premature termination of translation or to read-through. In spite of these perceived problems, a majority of the observed reassignments involve stop codons.

Osawa and Jukes (1989)(1995) proposed that the deleterious effect of codon reassignment could be avoided if the codon first disappeared from the genome. Changes in the translational system would occur when the codon was absent, and when the codon reappeared it would be translated as a different amino acid. Following Schultz and Yarus (1996), we call this the codon disappearance (CD) mechanism. Schultz and Yarus (1994)(1996) proposed an alternative ambiguous intermediate (AI) mechanism that does not require the codon to disappear. Instead, the codon is translated ambiguously as two different amino acids during the period of reassignment. Some cases of ambiguous translation are known (Lovett et al. 1991; Santos et al. 1997; Matsugi et al. 1998), and it is possible that other cases have passed through such an ambiguous intermediate stage.

In this article, we present a unified model for codon reassignment that includes both CD and AI mechanisms as special cases and introduce two other possible mechanisms. We refer to this as the gain-loss model, as it is based on our observation that codon reassignments involve a gain and a loss. By loss, we mean the deletion of the gene for the tRNA or RF originally associated with the codon to be reassigned or the loss of function of this gene due to a mutation or base modification in the anticodon. By gain, we mean the gain of a new type of tRNA for the reassigned codon (e.g., by gene duplication) or the gain of function of an existing tRNA due to a mutation or a base modification, enabling it to pair with the reassigned codon.

We consider two specific examples. First, in the canonical code, AUU, AUC, and AUA are all Ile, and AUG is Met. In animal mitochondria, AUA is reassigned to Met. Most organisms require two tRNAs to translate Ile codons. One tRNA has a GAU anticodon, and this translates AUU and AUC codons. The other has a K2CAU anticodon, where K2C is Lysidine, a modified C base that is capable of pairing with A in the third position of the AUA codon. The Met tRNA has a CAU anticodon and pairs only with AUG. The Lysidine modification is known in Escherichia coli (Muramatsu et al. 1988), and this tRNA gene is also found in all available complete genomes of proteobacteria (B. Tang, P. Boisvert and P. G. Higgs, unpublished results) and in several protist mitochondrial genomes (Gray et al. 1998). The same mechanism is presumed to operate in all these cases. The Lysidine tRNA is absent in animal mitochondrial genomes, and the tRNA-Met is modified so that it can pair with both AUG and AUA codons. This can happen either by a mutation to UAU or by base modification to f5CAU (Tomita et al. 1999). Thus, in our model, the loss represents the deletion of the K2CAU gene and the gain represents the gain of function of the tRNA-Met. The second example is the reassignment of UGA from stop to Trp. This involves the loss of the RF binding to this codon (Tomita et al. 1999), and the gain of function of the tRNA-Trp by mutation and subsequent base modification from a CCA anticodon to U*CA, where U* is a modified U that pairs with purines but not with pyrimidines.

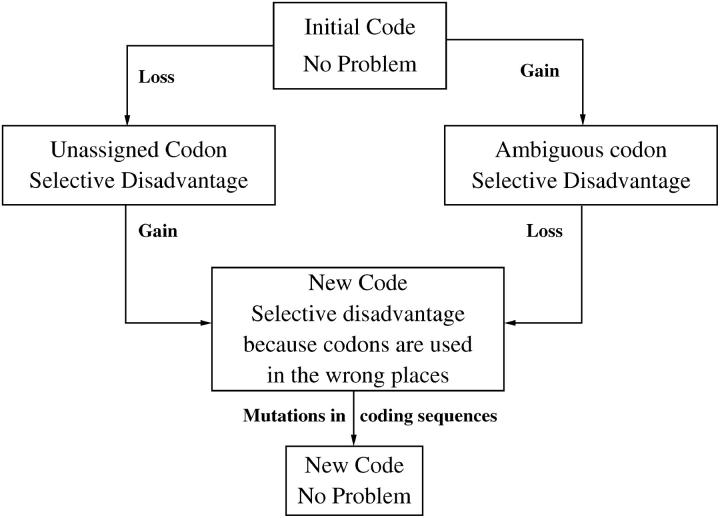

Although the details of the molecular event causing the gain and loss to differ for each case of codon reassignment, the common gain-loss framework (see Figure 1) applies to all of them. We begin with an organism following the canonical code and end with an organism with a modified code, in which both gain and loss have occurred. For the CD mechanism, the change is initiated by the disappearance of the codon undergoing reassignment prior to the fixation of loss or gain. The codon remains absent during the intermediate stage of reassignment until the fixation of a subsequent gain or loss event leads to the establishment of the new code. In that case, the gain and loss events will be selectively neutral, because in the absence of the codon the changes in the tRNAs make no difference to the organism. Therefore, the temporal order of gain and loss events is irrelevant. If the codon does not disappear, the order of gain and loss events is important. In the AI mechanism, the gain occurs before the loss. Two tRNAs can associate with the codon, and hence the codon will sometimes be mistranslated, causing a selective disadvantage for the organism. If the loss then occurs, the codon is no longer ambiguous, and a new code has been established. However, there is still a selective disadvantage because the organism is using the codon in places where the old amino acid is required. As mutations to other synonymous codons occur, this disadvantage will gradually disappear. The reassigned codon can also begin to appear in positions where the new amino acid is required, and this will not cause a selective disadvantage.

Figure 1.—

A schematic of the codon reassignment process interpreted in terms of the gain-loss framework. The strength of selective disadvantage depends on the number of times a codon is used. There is no selective disadvantage if the codon disappears.

A third possible mechanism is characterized by the loss occurring first, creating a state where there is no specific tRNA for the codon. The subsequent occurrence of a gain establishes the new code. We call this the unassigned codon (UC) mechanism. In the unassigned state there will be a selective disadvantage because translation will be inefficient. We presume that, after loss of the tRNA, some other tRNA has some degree of affinity for the codon, and that eventually an amino acid will be added for this codon, permitting normal translation to continue. In some cases (Yokobori et al. 2001), loss of a specific tRNA can occur with little penalty because another more general tRNA is available that can pair quite well with the codon in question. For example, in Echinoderm, Hemichordate, and Platyhelminthes mitochondria, an Ile tRNA with a GAU anticodon can pair with the AUA codon in the absence of the specific tRNA (with Lysidine in the wobble position) mentioned above. Also, in canonical code, AGA and AGG are Arg, but the corresponding tRNA-Arg has been lost from animal mitochondrial genomes. In some phyla, the AGR codons are unassigned and are absent from the genomes. In other phyla, a gain has also occurred: the Ser tRNA is modified to either UCU or m7GCU, which pairs with all four AGN codons (Matsuyama et al. 1998). In the Urochordates, there has been a gain of a new tRNA-Gly specific to AGR codons (Yokobori et al. 1993; Kondow et al. 1999). Thus several different responses to the loss of the original tRNA-Arg have occurred.

The gain-loss framework described here is related to the model of compensatory mutations (Kimura 1985). This model considers two genes with two alleles 0 and 1, such that both genes are in the 0 state initially. Each of the 1 alleles has a deleterious effect when present alone. When both mutations occur together, they compensate for one another and the fitness of the 11 state is assumed to be equal to the 00 state. Kimura showed that pairs of compensatory mutations can accumulate relatively rapidly, and this is one form of neutral evolution. A specific place where compensatory mutations are frequent is in the paired regions of RNA secondary structures. A population genetics theory for compensatory substitutions in RNA has been given by Higgs (1998). A key point is that the pair of mutations can be fixed either at two successive times or simultaneously. For example, if the population is initially GC, a mutation at one site can create a GU pair that goes to fixation as a slightly deleterious allele, and a second mutation can create an AU pair that compensates for the first change and then becomes fixed. Alternately, if there is a significant selective disadvantage to the GU pair, it is likely to remain at very low frequencies in the population and not go to fixation. If a second mutation occurs in a GU sequence, this creates an AU sequence that can spread as a compensatory neutral pair. In this case both the A and the U mutations become fixed simultaneously and there is no period where the GU variant spreads throughout the population. When real RNA sequences are analyzed (Savill et al. 2001), the rate of double substitutions is high compared to that of single substitutions, suggesting that this mechanism of simultaneous fixation of compensatory pairs is frequent. This brings us to the fourth possibility that can occur within our framework, which we call the compensatory change (CC) mechanism. We presume that gain and loss events are occurring continually in genomes at some low rate, creating individuals with a selective disadvantage because of ambiguous or unassigned codons. If this disadvantage is substantial, these variants are unlikely to reach high frequencies in the population. However, if the compensatory gain or loss occurs in one of these individuals, the gain and loss may then spread simultaneously through the population.

Our model concerns historical changes in the code that occurred after the establishment of the canonical code. It is likely that there were also prehistoric changes that led to the establishment of the canonical code before the LUCA. During this prehistoric stage, the code may have had <20 amino acids, and changes may have involved the addition of a new amino acid to the code. The coevolution theory (Wong 1975, 1976) considers the way the increase in amino acid diversity in the code was correlated to the synthesis of new amino acids. It has been argued (Szathmary 1991) that codon swapping reassignments driven by directional mutation pressure could have played a role in establishing the canonical code. Moreover, the canonical code appears to be optimized so as to reduce the deleterious effects of nonsynonymous substitutions. Tests have shown that the canonical code is better than almost all randomly reshuffled codes in this respect (Freeland and Hurst 1998; Freeland et al. 2000). A specific model for code buildup and optimization has been investigated (Ardell and Sella 2001; Sella and Ardell 2002) with the aim of understanding the pattern of amino acid associations of codons and the observed redundancy of the canonical code. It is likely that reassignments of sense codons or capture of nonsense codons could occur more easily during the early period of evolution when various pathways of establishing an optimal code were being explored. On the other hand, the negative selective effects of a reassignment process after the optimal canonical code has been established are likely to be very high. This puts severe restrictions on the possible reassignments that can occur in the postcanonical code era.

Although optimization of the code may have been important in the establishment of the canonical code, we do not believe that historical codon reassignments have been driven by selection for changes that improve on the canonical code. All the present-day alternative codes are much better than random codes, and the variant codes seem to be slightly worse than the canonical code (Freeland et al. 2000). Our view is that reassignments arise due to chance gain and loss events that become fixed in the population. It is the strength of the negative selective effects acting during the period of reassignment that controls the rate of reassignment and the mechanism by which it occurs. Possible differences in fitness between the codes before and after completion of the reassignment are most likely negligible with respect to the selective effects occurring during the reassignment.

Having described the four possible mechanisms within our framework, we now present a population genetics model in which all four of these mechanisms can be shown to occur. We use simulations to investigate the relative frequency of the mechanisms.

THE MODEL

We consider an asexual, haploid population of N individuals, each possessing a genome of L DNA bases, representing protein-coding regions. Noncoding regions are ignored. A target protein sequence is specified, consisting of L/3 amino acids or stops. The DNA sequences of the population evolve under mutation, selection, and drift. The fitness of a DNA sequence is determined by how close its specified protein is to the target. Translation of the DNA is performed initially according to the canonical code, but when the code changes different organisms in the population may be translated by different codes. For every amino acid that is different from the target amino acid (missense mutations) there is a factor (1 − s) in the fitness. There is a factor (1 − sstop) in the fitness for every stop where an amino acid should be and for every amino acid where a stop should be (nonsense mutations). The fitness of a sequence with j missense and k nonsense mutations is w = (1 − s)j(1 − sstop)k.

Each individual has a parent chosen randomly from the previous generation with a probability proportional to its fitness. The DNA sequence of the offspring is copied from the parent. Mutations occur with a probability u per site. Each base is replaced by one of the other three bases with equal probability. Each individual begins with a genome that exactly specifies the target protein. As mutations accumulate, the population reaches a state of mutation-selection balance where an individual typically differs from the target at a few points. (Note that we choose parameter values where the population is not subject to Muller's ratchet.)

In each run we consider only one codon reassignment, and we specify in advance which codon will be reassigned. Each individual possesses a loss gene and a gain gene with two alleles, 0 or 1. If loss = 0, the original tRNA is still present and functional in the genome. If loss = 1, the original tRNA has been deleted or has become dysfunctional due to a deleterious mutation. If gain = 0, a new tRNA is not yet available to translate the codon. If gain = 1, a tRNA capable of translating the codon with a new meaning has been acquired. Four types of individuals are defined by the gain and loss genes. Type 00 individuals use the old genetic code. Type 11 individuals use the new code, and the DNA sequence is translated according to the new code at the point when its fitness is calculated. Type 01 individuals have an unassigned codon. A penalty of (1 − sunas) is associated with each unassigned codon in a genome. Type 10 individuals have an ambiguous codon. Roughly half of the occurrences of this codon will be wrongly translated. Therefore a fitness contribution of (1 − s)1/2 is associated with such a codon whenever it appears in a position where the target is either the old or the new amino acid. If the codon appears in a position where the target is neither of these, it will always be wrong; therefore, a factor of (1 − s) applies.

The probabilities of a gain and a loss occurring per generation per whole population are Ug and Ul. If a gain or loss occurs then it is implemented in one random individual. Mutation occurs from the 0 to the 1 allele in each case and we do not consider reversals of these changes. Thus, the simulation will eventually end up with all individuals in the 11 state. However, for some parameter values the population remains in the 00 state for as long as it is feasible to run the simulations. The results presented below are for parameter values where the codon reassignment occurred in a reasonable time. By following the sequence of gain and loss events in our in silico experiment, we are able to determine the mechanism responsible for the reassignment of a codon and the frequency of occurrence of each mechanism. When counting the number of times each mechanism occurs, the mechanism is defined as CD if the codon disappears from the population during the reassignment period, irrespective of the order of the gain and loss. The underlying mechanism is CC if the gain and loss are fixed simultaneously. If the codon does not disappear, the mechanism is AI if the gain is fixed first and UC if the loss is fixed first.

RESULTS

Four specific examples:

The following examples concern the reassignment of the AUA codon. The number of Ile codons in the target sequence was set to 12, 24, or 36. There were 4 codons for each of the 19 other amino acids plus a single stop codon. Thus the total number of codons was 89, 101, or 113. The genome lengths used were quite short due to constraints on computing time. The simulations were initiated with equal numbers of AUA, AUU, and AUC codons (i.e., #AUA = 4, 8, or 12 initially). The initial DNA sequence for the non-Ile codons was chosen randomly from codons corresponding to the target. The population size was N = 1000, and Ug = Ul = 0.1. The other parameters were varied between simulations.

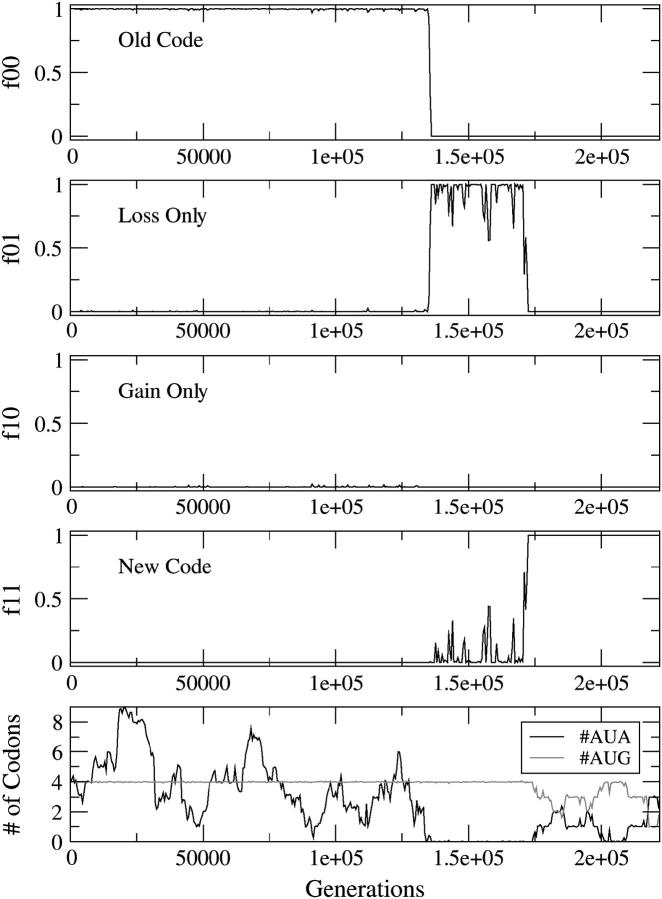

Figure 2 shows an example of the CD mechanism. The frequency of type ij individuals is denoted fij. The simulation begins with f00 = 1 and ends with f11 = 1. There is an intermediate stage where f01 goes to unity, indicating that the loss happens first. However, in Figure 2, bottom, it is clear that #AUA goes to zero just before f01 increases. Hence, the reassignment process is initiated by the disappearance of the AUA codons. In this example, the selection against missense mutations, s, is much greater than the mutation rate, u. This means that the mean number of codons for each amino acid is almost exactly equal to the number in the target sequence. As AUG is the only Met codon, #AUG stays fixed close to 4 until the codon reassignment occurs. In contrast, #AUA can fluctuate due to third-position mutations. After the change, both AUA and AUG code for Met; consequently #AUA + #AUG = 4.

Figure 2.—

Reassignment of AUA via the CD mechanism. The frequencies of the four types of individuals are shown as a function of time. The bottom shows the mean number of AUA and AUG codons per genome. The parameters are s = sstop = sunas = 0.05, u = 0.0001, and #AUA = 4 in the original sequence.

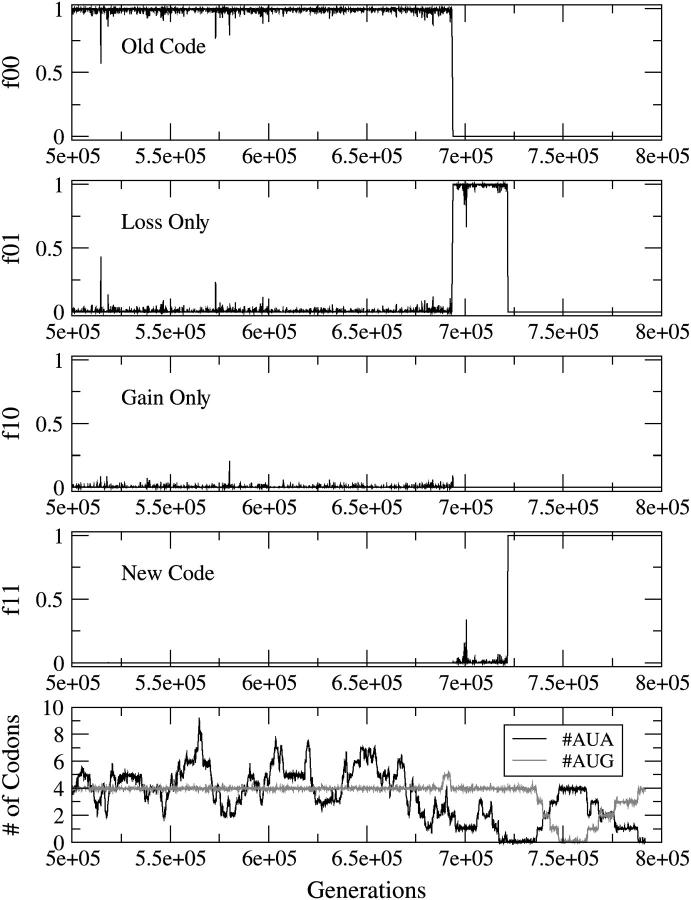

Figure 3 shows a reassignment occurring by the AI mechanism. #AUA is increased to 12 initially, which makes it less likely for the codons to disappear due to random drift. Moreover, s is reduced, which makes the penalty for the AI state less severe. The gain happens before the loss. #AUA does not disappear during the intermediate stage; however, it remains around 4 during most of the AI stage—substantially less than the 12 AUA codons originally present. This suggests that selection is acting against the ambiguous codon during the intermediate stage. Another effect of reduction of s is that the number of Met codons fluctuates around its optimum value of 4, in contrast to Figure 2.

Figure 3.—

Reassignment of the AUA codon via the AI mechanism. The parameters are s = sstop = sunas = 0.01, u = 0.0001, and #AUA = 12 in the original sequence.

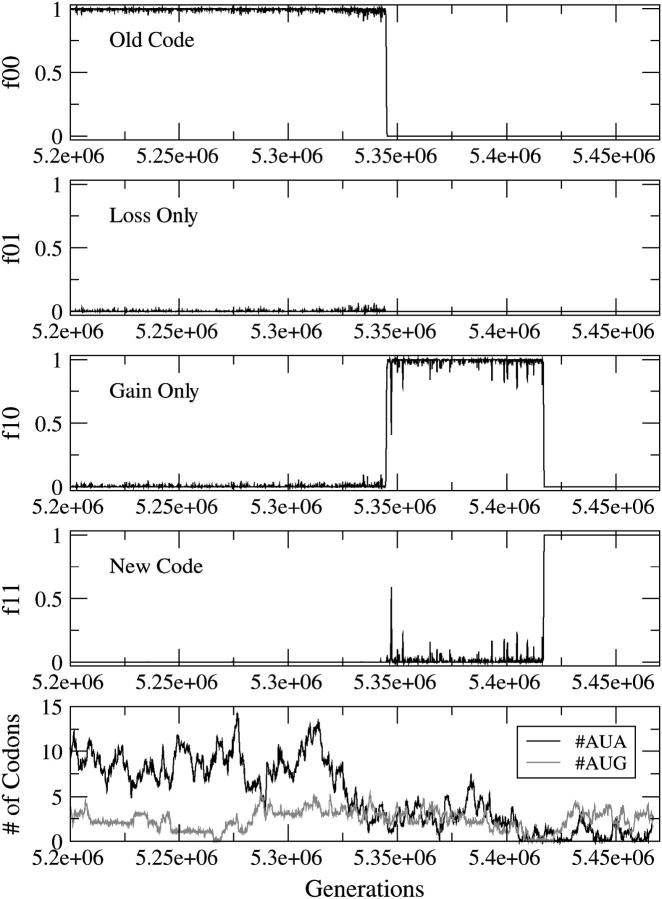

Figure 4 shows the reassignment of AUA via the UC mechanism initiated by the loss of the tRNA − Met with Lysidine in the wobble position. The penalty against the unassigned codon is smaller than the penalty against a missense or nonsense translation. This would be the case if another tRNA were available to translate the unassigned codon reasonably well in the absence of the original specific tRNA. The loss occurs while the #AUA is nonzero, leaving the AUA codons unassigned. #AUA is seen to fluctuate during the intermediate stage (when f01 ∼ 1) and eventually goes to zero during the later part of the intermediate stage. This is a manifestation of selection acting to minimize the use of the unassigned codon after the disappearance of its specific tRNA. However, since the number of codons is small, the disappearance could also be due to random drift. For lower values of sunas, the #AUA remains nonzero for the whole of the intermediate stage. The frequencies of the four types of individuals are shown as a function of time in the top four parts. The bottom shows the mean number of AUA and AUG codons per genome.

Figure 4.—

Reassignment of AUA by the UC mechanism. The frequencies of the four types of individuals are shown as a function of time in the top four parts. The bottom part shows the mean number of AUA and AUG codons per genome. The parameters are s = sstop = 0.02, sunas = 0.007, u = 0.0001, and #AUA = 4 in the original sequence.

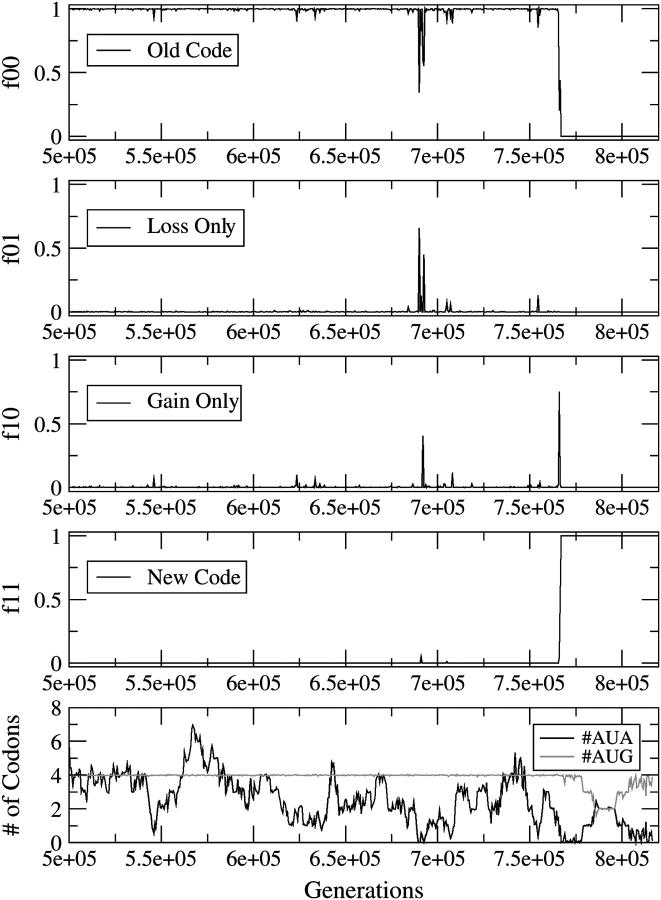

Figure 5 provides evidence of the reassignment of AUA from Ile to Met via the compensatory change mechanism. There is no intermediate period and neither f01 nor f10 is ever close to 1. The new code replaces the old code when the gain and loss are fixed in the population simultaneously.

Figure 5.—

Reassignment of AUA by the CC mechanism. The parameters are s = sstop = sunas = 0.05, u = 0.001, and #AUA = 4 in the original sequence.

Factors affecting the frequencies of the four mechanisms:

We carried out many runs of the simulation to investigate the frequency of the different reassignment mechanisms. For each set of parameters, 20 runs were carried out using different random-number seeds. Table 1a shows the effect of varying s. These examples correspond to AUA reassignment, and in this case the stop codon is not particularly relevant. Therefore we set sstop = s to reduce the number of parameters. To determine the value of sunas, we must consider two factors. There will be a penalty for the delay involved in waiting for a poorly matching tRNA to come along, and there will be a penalty due to incorrect translation of the codon in cases where the wrong amino acid is inserted. For this set of runs, we set sunas = s, for simplicity. This is appropriate if an incorrect amino acid is inserted for every occurrence of the unassigned codon, but the delay effect is negligible. When s = 0.05, almost all changes occur via the CD mechanism. As selection is reduced, there is a shift from predominantly CD to predominantly AI. This makes sense, because with weaker selection there is a smaller penalty against ambiguous codons. The UC mechanism is less frequent than the AI mechanism, because of an asymmetry in the way we assigned fitness to ambiguous and unassigned codons. We supposed that the ambiguous codon was translated incorrectly only half the time, so that the penalty was (1 − s)1/2 per ambiguous codon, whereas the penalty for an unassigned codon was (1 − s). Additionally, we see that the CC mechanism occurs occasionally and that the frequency of CC appears to be higher for larger s (although the number of runs is too small to demonstrate this statistically). We would expect the CC mechanism to be most relevant under conditions where it is difficult for either the gain or the loss to be fixed in the population individually, i.e., when there is a strong penalty against both the ambiguous and unassigned states. The mean fixation time for the establishment of the new code was also found to increase with increasing s, as expected, since the deleterious effects of strong negative selection make it more difficult to implement code change.

TABLE 1.

The frequencies of four mechanisms of codon reassignment measured in simulations

| CD | UC | AI | CC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Varying selection strength sa | ||||

| s = 0.05 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| s = 0.02 | 13 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| s = 0.01 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 0 |

| b. Varying the number of Ile codonsb | ||||

| #AUA = 4 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 0 |

| #AUA = 8 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 0 |

| #AUA = 12 | 1 | 2 | 17 | 0 |

| c. Varying sstopc | ||||

| sstop = 0.01 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 1 |

| sstop = 0.02 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| sstop = 0.04 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| d. Varying GC mutational pressured | ||||

| πG = 0.25 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 0 |

| πG = 0.3 | 4 | 2 | 14 | 0 |

| πG = 0.4 | 12 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| e. Varying sunase | ||||

| sunas = 0.02 | 12 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| sunas = 0.007 | 6 | 11 | 3 | 0 |

| sunas = 0.003 | 1 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| f. Varying the advantage of genome size reduction δf | ||||

| δ = 0 | 6 | 11 | 3 | 0 |

| δ = 0.001 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 |

| δ = 0.004 | 1 | 18 | 1 | 0 |

Results refer to simulations of AUA codon reassignment, except for c, which is for UGA.

#AUA = 4, u = 0.0001, s = sstop = sunas in all cases.

u = 0.0001, s = sstop = sunas = 0.01.

With sunas = s = 0.01, u = 0.0001, #UGA = 4 in the original sequence.

#AUA = 8, u = 0.0001, s = sstop = sunas = 0.01.

With s = sstop = 0.02, u = 0.0001, #AUA = 4.

s = sstop = 0.02, sunas = 0.007, u = 0.0001, #AUA = 4.

Table 1b shows the effect of varying the number of Ile codons. As described above, #AUA initially was 4, 8, or 12. As #AUA increases, there is a trend away from the CD mechanism toward the AI mechanism. The mean fixation time for the new code via the AI mechanism increases with #AUA, since the cumulative deleterious effects of negative selection on many codons make it more difficult to establish the new code. The time taken for the CD mechanism also increases with the number of codons, because it is more difficult for a larger number of codons to disappear by chance. However, the time for the CD mechanism increases faster, hence the shift from CD to AI with increasing codon number.

As reassignment of UGA from stop to Trp is one of the most frequently observed reassignments, we wished to consider this case specifically in the model. The target sequence used in this case had 93 codons for a full range of amino acids, plus 4 stop codons. Each of the four stop codons was set to UGA in the initial DNA sequences. The loss gene represents a RF, which recognizes UGA as a stop codon, and the gain gene represents the Trp tRNA. We begin in Table 1c with sstop = 0.01, i.e., the same as s, and consider the effect of increasing sstop while s is fixed. The choice of sunas depends on what we would expect to occur if the stop codon became unassigned. In the absence of a specific RF, would translation terminate anyway because another less specific release factor was available, or would read-through occur? In the latter case the selection against an unassigned stop codon should be as high as the selection against a nonsense translation (sstop), but in the former case it should be less. For this simulation, we set sunas = s, for simplicity and in the absence of clear biological knowledge of what happens in this case. If the gain precedes the loss, an ambiguous intermediate stage is encountered during which UGA is read simultaneously as both stop and Trp. In this case, a penalty of (1 − sstop)1/2 is associated with the UGA codon whenever it corresponds to a stop or a Trp in the target protein sequence in Table 1c. As sstop increases, the mechanism changes from predominantly AI to predominantly CD. Since the penalty against an unassigned stop codon was kept fixed (sunas = 0.01), a significant number of changes occur via the UC mechanism for large values of sstop. However, if the penalty against an unassigned UGA was as large as sstop, CD would be the only viable mechanism. We emphasize that even in large genomes containing many genes, the number of UGA codons can be quite small if UAR are the primary codons used for translation termination. Under such circumstances, the reassignment of UGA can happen relatively easily via the CD mechanism and this provides a plausible reason for the large number of observed reassignments involving the UGA codon.

For the runs in Table 1c, the CD mechanism takes place when #UGA goes to 0 due to random drift. However, directional mutation pressure can also cause the disappearance of a codon (Osawa and Jukes 1995). In the case of the AUA reassignment, biased mutation away from A can cause AUA codons to be replaced by AUU or AUC and make it easier for the CD mechanism to occur, even if the total number of Ile codons is quite large. For the runs in Table 1d, we suppose that the rate of mutation from base i to base j is given by rij = απj, where πj is the equilibrium frequency of base j. The average mutation rate is u = ∑i∑j≠iπirij. We varied the frequency πG, keeping πC = πG, and πA = πU = 0.5 − πG. We chose α so that u was kept fixed at 0.0001. In these runs, #AUA was 8. Under these conditions the predominant mechanism is AI when the base frequencies are equal. As the mutational bias toward GC is increased, the mechanism switches toward predominantly CD, which confirms the important influence of directional mutation pressure on the CD mechanism.

In Table 1e we consider variation in sunas while s is fixed at 0.02. When sunas is also 0.02, CD is the predominant mechanism and UC is rare because of the asymmetry in selection against unassigned and ambiguous codons discussed above. Table 1e shows that when sunas is reduced, the UC mechanism becomes more frequent than either AI or CD. In this case there is an asymmetry that favors unassigned codons over ambiguous ones. A low value of sunas corresponds to a case where another tRNA for the same amino acid would be able to translate the codon after loss of the specific tRNA (Yokobori et al. 2001). In simulations where sunas is made even smaller than the values shown, the intermediate unassigned state can be sustained for a very long time. This corresponds to a case of reduction of the necessary number of tRNAs for a codon family without change in the genetic code (e.g., the number of tRNAs has been reduced to 1 in all the four-codon families in mitochondrial genomes).

The deletion of a tRNA can confer a selective advantage to an individual since it leads to a reduction in the genome size—the genome streamlining hypothesis (Andersson and Kurland 1991, 1995). Although Knight et al. (2001b) have argued against this hypothesis, it could be an important effect in small genomes like that of mitochondria, where the length of a tRNA is not negligible compared to the total genome length. In the context of our model, selection for reduction in genome length provides an advantage to the loss event that can counteract the negative selection from unassigned codons. To investigate this effect, we consider the rate of genome replication to be proportional to its length and that deletion of a tRNA will confer a selective advantage dependent on δ, the relative length of a tRNA gene to the total genome length. A genome after the loss is a factor (1 − δ) shorter, and its fitness is a factor 1/(1 − δ) larger than a genome in which the loss has not occurred. Reclinomonas americana is a protist with a relatively large mitochondrial genome (L = 69,034) (Gray et al. 1998). Both the UGA and the AUA codons retain their canonical assignments in this organism, and the genome still possesses the tRNA-Ile specific to the AUA codon. This genome therefore gives us a good idea about the state of the mitochondrial genome before these reassignments occurred. The mean length of a tRNA in Reclinomonas is 72, and δ = 0.001. A second example is the human mitochondrial genome, which is typical of most animal mitochondrial genomes. This has a length of 16,571 and a mean tRNA length of 69; hence, δ = 0.004. Table 1f shows that as δ increases the UC mechanism becomes predominant. For the values of the selection coefficients used here, there is no significant difference in the frequencies between the runs with δ = 0 and δ = 0.001, but the number of UC cases is significantly higher than either of these when δ = 0.004. Unfortunately we do not know the values of the selection coefficients s, sunas, and sstop in the real case, and they may be much smaller than the values we are using in these simulations. This means that this effect could well be significant in genomes of the size of Reclinomonas. Some of the important changes that have occurred in the mitochondrial translation system appear to have been initiated by tRNA loss. We also note that deletion of the tRNA potentially confers a selective advantage simply from the fact that the tRNA no longer needs to be synthesized. This is a contribution to δ that is not proportional to the genome length, but that would produce the same effect as that considered above.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

These simulations illustrate qualitative trends in the frequencies of the mechanisms. We would like to be able to identify the mechanism responsible for each observed reassignment event. We are hindered here by a lack of information on the fitness costs associated with the various possible intermediate stages of the codon reassignment process. If there is an ambiguous codon, what are the relative affinities of the two tRNAs? If a stop codon is ambiguous, what are the relative frequencies of termination and read-through? If a codon is unassigned, is there another tRNA that can step in and fulfill the role of the original tRNA? Does the delay to the translation process caused by unassigned codons have a significant effect on the fitness, or is it merely the incorrect translation of a codon that would be important? Even though the fitness costs of an ambiguous or unassigned codon are not yet available, much work has been done to shed light on the detailed molecular processes responsible for efficient translation.

Recent works have shown the presence of various error-correcting mechanisms working at every stage to ensure the accuracy of translation (Ibba and Soll 1999). When two competing tRNAs with distinct anticodons are available to decode a particular codon, as in the ambiguous intermediate case, which of the two eventually wins would be determined by factors such as the efficiency of binding between the charged tRNA and the elongation factor protein (Lariviere et al. 2001) and efficiency of the codon-anticodon pairing at the ribosome and its effect on proper insertion of an amino acid into the growing polypeptide chain (Ogle et al. 2003). For the case of an unassigned codon, these factors will determine whether another noncognate tRNA, with an anticodon that mispairs with the corresponding unassigned codon at the wobble position, can be recruited and thereby used to extend the polypeptide chain in the absence of a better alternative? Such work was primarily motivated by experiments that indicate that the frequency of mistranslation events is low; ∼1 in 10,000 (Kurland 1992). Mistranslation, which can arise either due to the mispairing of codon and anticodon or due to mischarging of a tRNA, is qualitatively different from ambiguous translation of a codon considered here. During ambiguous translation, both the tRNAs in question have anticodons that can “correctly” pair with the same codon, and there is no reason to say that one or the other is a mistranslation. Also, the ambiguous state seems to arise through the gain of function of a new tRNA (usually by an anticodon change), not through the breakdown of the accuracy of translation of the original tRNA.

Another relevant point related to mistranslation is that it causes a loss of fitness since it results in nonoptimal proteins. The severity of the load imposed on an organism by mistranslation will depend on which types of amino acid substitutions result most often from mistranslations. The structure of the canonical genetic code appears to minimize the load due to mistranslation by placing similar amino acids on neighboring codons (Freeland and Hurst 1998; Freeland et al. 2000). Synonymous codons might also be subject to different frequencies of mistranslation. This would mean that replacement of all occurrences of a codon by another synonymous codon (as happens in the CD mechanism) might not be strictly neutral. This was not considered in our model, since we assumed that any fitness effects due to synonymous changes were negligible compared to nonsynonymous ones.

We would like to be able to predict which mechanisms of codon reassignment occur most frequently in real genomes. Unfortunately, real parameter values lie outside the range that can be simulated with the model: genomes should be much longer, population sizes larger, mutation rates lower, and selection coefficients most likely should be smaller. For simplicity, our model also assumes that all nonsynonymous changes have equal fitness effects. Allowing a distribution of fitness effects across sites would influence the relative frequencies of the mechanisms to some extent. Despite these uncertainties, we can make a few general statements.

First, all these mechanisms become more difficult when genome sizes are larger. This is presumably the main reason for the larger number of observed changes in mitochondria (with small genomes and high mutation rates) than in nuclear genomes. The CD mechanism is most likely in cases where there are initially few copies of the codon to be reassigned. Thus, it could well apply for stop codon reassignments and for cases when there is a strong mutational bias that causes the reduction in number of one of a family of synonymous codons. It seems less likely than the other mechanisms for most reassignments other than stop codons. The fact that so many real cases of reassignments are now known suggests to us that our intuition regarding the severity of ambiguous and unassigned codons may have been wrong. Our results suggest that many of the cases where changes have occurred may have passed through one of these two intermediates.

Another line of argument favors the AI and UC mechanisms over the CD. The gain and loss events that lead to a reassignment are independent, rare events involving distinct tRNAs or RFs. According to the CD mechanism, the two events occur by chance during a period in which the codon disappears. This means that if a gain (or loss) occurs that affects a particular codon, then the corresponding loss (or gain) must occur for the same codon soon afterward, and both these changes must spread through the population as neutral mutations. There is no particular reason why the two rare events should be associated with the same codon. The AI and UC mechanisms do not suffer from this problem. In both cases, after the first gain (or loss) there is a selective advantage for the loss (or gain) for the same codon. Thus the gain and loss events are linked by selection in these two mechanisms, but not in the CD mechanism. In the simulations, both gain and loss occurred at a rate of 0.1 per population per generation. This high rate was used to ensure that a supply of gain and loss mutations was available, some of which were able to go to fixation in the population within a reasonable simulation time. Consequently, it is easy for both gain and loss events to be present in the population at the same time and to be fixed neutrally. This favors the CD mechanism. If the gain and loss rate were lower in our simulations, we would expect a reduction in the frequency of CD relative to that of AI and UC.

It is worth noting that we set the rates of the gain and loss events to be equal. If these rates were not equal, this would affect the relative frequencies of AI and UC mechanisms in an obvious way. A loss event seems simpler than a gain in most cases. It is not difficult to delete a gene, whereas most of the gains discussed here involve creation of a modified base. This means that the enzyme for base modification has to appear from somewhere and learn to recognize the appropriate tRNA. For these reasons we might expect the loss rate to be higher than the gain rate in real life, and hence the UC mechanism would be more frequent.

The CC mechanism was never common for any of the parameter sets used. However, we would expect this to become more frequent in longer genomes, where CD is unlikely and where there would be large penalties for AI and UC states.

Directional mutation pressure is beneficial for CD, UC, and AI mechanisms. In the CD mechanism, while not essential for ensuring codon disappearance, it makes this more likely in longer genomes. Also, by considerably reducing the number of codons undergoing reassignment via the AI or UC mechanisms, it helps offset the deleterious effect of ambiguous translation or an unassigned codon.

In summary, this article makes several important contributions to the understanding of the codon reassignment process. By introducing the gain-loss model of reassignment, we have provided a unified framework for discussing two of the most frequently cited mechanisms (CD and AI) of code change. Expressing the problem in this way highlights the similarity with the theory of compensatory mutations that has been studied in other contexts. Within our framework, the UC and CC mechanisms appear as natural alternatives to CD and AI. The framework is sufficiently general to apply to many different reassignment events, despite the fact that the molecular events causing the gains and losses are different in every case. In addition, we have presented a well-defined population genetics model, shown that all four mechanisms occur in the simulations, and discussed the influence of the parameters on the relative frequency of the mechanisms. We are now investigating the many known cases of codon reassignment to determine which mechanisms appear to have been most frequent in real organisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Canada Research Chairs.

References

- Andersson, S. G., and C. G. Kurland, 1991. An extreme codon preference strategy: codon reassignment. Mol. Biol. Evol. 8: 530–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, S. G., and C. G. Kurland, 1995. Genomic evolution drives the evolution of the translational system. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 73: 775–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardell, D. H., and G. Sella, 2001. On the evolution of redundancy in genetic codes. J. Mol. Evol. 53: 269–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeland, S. J., and L. D. Hurst, 1998. The genetic code is one in a million. J. Mol. Evol. 47: 238–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeland, S. J., R. D. Knight, L. F. Landweber and L. D. Hurst, 2000. Early fixation of an optimal genetic code. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. W., B. F. Lang, R. Cedergren, G. B. Golding, C. Lemieux et al., 1998. Genome structure and gene content in protist mitochondrial DNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 865–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs, P. G., 1998. Compensatory neutral mutations and the evolution of RNA. Genetica 102/103: 91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibba, M., and D. Soll, 1999. Quality control mechanisms during translation. Science 286: 1893–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M., 1985. The role of compensatory neutral mutations in molecular evolution. J. Genet. 64: 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, R. J., S. J. Freeland and L. F. Landweber, 2001. a Rewiring the keyboard: evolvability of the genetic code. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, R. D., L. F. Landweber and M. Yarus, 2001. b How mitochondria redefine the code. J. Mol. Evol. 53: 299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondow, A., T. Suzuki, S. Yokobori, T. Ueda and K. Watanabe, 1999. An extra tRNAGly(U*CU) found in ascidian mitochondria responsible for decoding non-universal codons AGA/AGG as glycine. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 2554–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurland, C. G., 1992. Translational accuracy and the fitness of bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 26: 29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lariviere, F. J, A. D. Wolfson and O. C. Uhlenbeck, 2001. Uniform binding of aminoacyl-tRNAs to elongation factor Tu by thermodynamic compensation. Science 294: 165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett, P. S., N. P. Ambulos, Jr., W. Mulbry, N. Noguchi and E. J. Rogers, 1991. UGA can be decoded as tryptophan at low efficiency in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 173: 1810–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsugi, J., K. Murao and H. Ishikura, 1998. Effect of B. subtilis TRNA(Trp) on readthrough rate at an opal UGA codon. J. Biochem. 123: 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama, S., T. Ueda, P. F. Crain, J. A. McCloskey and K. Watanabe, 1998. A novel wobble rule found in starfish mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 3363–3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu, T., S. Yokoyama, N. Horie, A. Matsuda, T. Ueda et al., 1988. A novel Lysine-substituted nucleoside in the first position of the anticodon of minor isoleucine tRNA from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 9261–9267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle, J. M., A. P. Carter and V. Ramakrishnan, 2003. Insights into the decoding mechanism from recent ribosome structures. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 28: 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa, S., and T. H. Jukes, 1989. Codon reassignment (codon capture) in evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 28: 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa, S., and T. H. Jukes, 1995. On codon reassignment. J. Mol. Evol. 41: 247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M. A. S., T. Ueda, K. Watanabe and M. Tuite, 1997. The non-standard genetic code for Candida spp.: an evolving genetic code or a novel mechanism for adaptation. Mol. Microbiol. 26: 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill, N. J., D. C. Hoyle and P. G. Higgs, 2001. RNA sequence evolution with secondary structure constraints: comparison of substitution rate models using maximum likelihood methods. Genetics 157: 399–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, D. W., and M. Yarus, 1994. Transfer RNA mutations and the malleability of the genetic code. J. Mol. Evol. 235: 1377–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, D. W., and M. Yarus, 1996. On malleability in the genetic code. J. Mol. Evol. 42: 597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sella, G., and D. H. Ardell, 2002. The impact of a message mutation on the fitness of a genetic code. J. Mol. Evol. 54: 638–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szathmary, E., 1991. Codon swapping as a possible evolutionary mechanism. J. Mol. Evol. 32: 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tomita, K., T. Ueda, S. Ishiwa, P. F. Crain, J. A. McCloskey et al., 1999. Codon reading patterns in Drosophila melanogaster mitochondria based on their tRNA sequences: a unique wobble rule in animal mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 4291–4297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J. T. F., 1975. A coevolution theory of the genetic code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72: 1909–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J. T. F., 1976. The evolution of a universal genetic code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73: 2336–2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori, S., T. Ueda and K. Watanabe, 1993. Codons AGA and AGG are read as glycine in ascidian mitochondria. J. Mol. Evol. 36: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori, S., T. Suzuki and K. Watanabe, 2001. Genetic code variations in mitochondria: tRNA as a major determinant of genetic code plasticity. J. Mol. Evol. 53: 314–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]