Abstract

We have examined the in vivo requirement of two recently identified nonessential components of the budding yeast anaphase-promoting complex, Swm1p and Mnd2p, as well as that of the previously identified subunit Apc9p. swm1Δ mutants exhibit synthetic lethality or conditional synthetic lethality with other APC/C subunits and regulators, whereas mnd2Δ mutants are less sensitive to perturbation of the APC/C. swm1Δ mutants, but not mnd2Δ mutants, exhibit defects in APC/C substrate turnover, both during the mitotic cell cycle and in α-factor-arrested cells. In contrast, apc9Δ mutants exhibit only minor defects in substrate degradation in α-factor-arrested cells. In cycling cells, degradation of Clb2p, but not Pds1p or Clb5p, is delayed in apc9Δ. Our findings suggest that Swm1p is required for full catalytic activity of the APC/C, whereas the requirement of Mnd2p for APC/C function appears to be negligible under standard laboratory conditions. Furthermore, the role of Apc9p in APC/C-dependent ubiquitination may be limited to the proteolysis of a select number of substrates.

UBIQUITIN-mediated proteolysis (Ciechanover 1994; Hochstrasser 1996) of cell cycle regulators is required for cell cycle transitions. In eukaryotes, the polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation of Pds1p/securin and mitotic cyclins is essential for the metaphase-to-anaphase transition and exit from mitosis. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), a large and complex member of the RING-finger family of E3 ubiquitin ligases, catalyzes the polyubiquitination of these and other substrates. RING-finger proteins have been shown to promote substrate in vitro ubiquitination in conjunction with E2s and a ubiquitin-activating system and are believed to recruit ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes to their cognate E3 complexes (Jackson et al. 2000). In Skp1/cullin-homology/F-box (SCF) and VHL/Elongin BC complexes, evidence suggests that the RING-H2 protein ROC1/Rbx1p recruits E2s to cullins (Kamura et al. 1999; Skowyra et al. 1999). In the case of the APC/C, APC2 contains a cullin-homology domain on its carboxy terminus (Yu et al. 1998; Zachariae et al. 1998) and, like other members of the cullin family, is thought to act as a scaffold that promotes substrate ubiquitination by bringing E2/RING-H2 complexes into close proximity with substrate/specificity factor complexes (Yu et al. 1998; Gmachl et al. 2000; Leverson et al. 2000; Tang et al. 2001).

In addition to APC11 and APC2, the APC/C comprises 11 other subunits (Page and Hieter 1999; Peters 1999; Zachariae and Nasmyth 1999). Structural homologs of these subunits are absent from other SCF-like complexes and their functions are poorly understood. Homologs of APC1, APC4, APC5, CDC26, and DOC1 are found throughout the eukaryotic kingdom, as are the three tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) proteins CDC16, CDC23, and CDC27. A fourth TPR protein, APC7, appears to be present only in multicellular eukaryotes, whereas Apc9p has been identified only in several fungi. In budding yeast, APC/C function is essential for viability in otherwise normal cells, although the APC/C is dispensable for cell survival in cells lacking both Pds1p and Clb/CDK activity. Deletion of most core APC/C subunits is therefore lethal, but APC/C subunits Doc1p, Cdc26p, and Apc9p are encoded by nonessential genes.

Regulation of mitotic APC/C activity is controlled by two specificity factors, Cdc20p and Cdh1p, both of which contain WD-40 repeats (Schwab et al. 1997; Visintin et al. 1997; Fang et al. 1998). Cdc20p and Cdh1p may bind directly to APC/C substrates and recruit them to the core complex, although the biochemical details of how substrates are recognized by the APC/C are poorly understood (Burton and Solomon 2001; Hilioti et al. 2001; Pfleger et al. 2001; Schwab et al. 2001). At the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, APCCdc20p catalyzes the ubiquitination of Pds1p, releasing Esp1p/separase, which then cleaves Scc1p/cohesin to initiate sister-chromatid separation and the onset of anaphase (Zachariae and Nasmyth 1999; Amon 2001; Cohen-Fix 2001; Nasmyth et al. 2001). APCCdc20p also ubiquitinates Clb5p and a fraction of Clb2p (Shirayama et al. 1999; Yeong et al. 2000; Irniger 2002) and the resulting decrease in B-type cyclin activity, coupled with release of the phosphatase Cdc14p from the nucleolus, activates Cdh1p. As cells exit from mitosis, APCCdh1p ubiquitinates the remaining B-type cyclins and other components of the mitotic apparatus such as Ase1p, Kip1p, Cin8p, and Cdc5p (Juang et al. 1997; Charles et al. 1998; Shirayama et al. 1998; Gordon and Roof 2001; Hildebrandt and Hoyt 2001), as well as Cdc20p itself (Prinz et al. 1998; Goh et al. 2000).

Recently several groups have identified Swm1p and Mnd2p as new nonessential budding yeast APC/C components by immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry of the purified complex (Yoon et al. 2002; Hall et al. 2003; Schwickart et al. 2004). Structural homologs of both proteins were also identified in fission yeast APC/C complexes (Yoon et al. 2002). SWM1 was previously shown to be required for meiotic spore wall maturation, whereas MND2 was first identified as being required for proper meiotic nuclear division in a survey of genes whose deletion causes meiotic defects (Ufano et al. 1999; Rabitsch et al. 2001). Little is known about the contribution of either protein to APC/C function. In this work we assess the in vivo requirement of Swm1p and Mnd2p, as well as that of Apc9p, another nonessential APC/C subunit for which limited functional data exist.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast genetic methods and media:

Standard yeast growth media (YPD) and dropout media [synthetic complete (SC)] was used as described in Rose et al. (1990). Yeast transformations were performed according to the method of Gietz et al. (1995). Loss of viability was assessed by replating on YPD at 25° and scoring microcolonies after overnight growth. Rescue of swm1Δ apc9Δ and swm1Δ cdc26Δ synthetic lethality (Table 5) was accomplished by mating YAP2888 (swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 pRS316-SWM1) with YVA433 (apc9Δ::KanMX) or YVA435 (cdc26Δ::KanMX) containing pRS424, pSG2 (pRS424-SWM1), pAP35 (pRS424-CDC16), pAP36 (pRS424-CDC23), or pAP37 (pRS424-CDC27). Diploids were sporulated and Ura+ Trp+ His+ G418-resistant spores were assessed for their ability to grow on 5-FOA. In some cases, Trp− Ura+ His+ G418-resistant spores were tested directly by retransforming in the 2μ vector bearing the relevant gene and assessing the ability of Trp+ transformants to grow on 5-FOA media.

TABLE 5 .

Synthetic lethality ofapcΔ double mutants can be rescued by overexpression of specific TPR proteins

| Genotype | 25° | 30° | 33° | 35° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| swm1Δ apc9Δ | − | ND | ND | ND |

| swm1Δ apc9Δ 2μ-CDC23 | +/− | ND | ND | ND |

| swm1Δ apc9Δ 2μ-CDC27 | +++ | +/− | − | ND |

| swm1Δ apc9Δ 2μ-CDC16 | − | ND | ND | ND |

| cdc26Δ | +++ | +++ | − | − |

| cdc26Δ 2μ-CDC23 | +++ | ND | − | ND |

| cdc26Δ 2μ-CDC27 | +++ | ND | − | ND |

| cdc26Δ 2μ-CDC16 | +++ | ND | +++ | +++ |

| swm1Δ cdc26Δ | − | ND | ND | ND |

| swm1Δ cdc26Δ 2μ-CDC23 | − | ND | ND | ND |

| swm1Δ cdc26Δ 2μ-CDC27 | − | ND | ND | ND |

| swm1Δ cdc26Δ 2μ-CDC16 | +++ | +/− | − | ND |

| apc9Δ cdc26Δ | +++ | +++ | − | − |

| apc9Δ cdc26Δ 2μ-CDC16 | +++ | ND | +++ | +++ |

ND, not determined.

Plasmids:

pOCF30 (pRS416-GAL1-PDS1) (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996) was kindly provided by Doug Koshland. pAP62 was constructed by subcloning an NheI-PstI fragment containing the ASE1-3XMYC cassette of pPB338 (generously provided by David Pellman) into the SpeI-PstI sites of pRS414-GAL1 (Mumberg et al. 1995). pMT634 (pGAL1-CLN2-HA URA3 LEU2 CEN) (Willems et al. 1996) was generously provided by Mike Tyers. pSG2 was constructed by subcloning a BamHI-NdeI cassette containing the SWM1 ORF flanked by ∼175 bp upstream and 225 bp downstream into pRS424 from the original rescuing clone. pVA117 was constructed by PCR amplification from the original rescuing clone of the MND2 open reading frame flanked by ∼500 bp upstream and 250 bp downstream into the ClaI-NotI sites of pRS426. See Table 1 for a list of strains and plasmids used in this article.

TABLE 1 .

Strains and plasmids

| Strain/plasmid | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| YPH499 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 | This study |

| YST74 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ1 cdc23-54 | Lamb et al. (1994) |

| YJL96 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| YAP645 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 apc11Δ::HIS3 leu2Δ1::apc11-13 pOCF30 | This study |

| YAP928 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 SWM1-13XMYC; HIS3MX6 | This study |

| YAP1146 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 pOCF30 | This study |

| YAP1148 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3 pOCF30 | This study |

| YAP1232 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 PDS1-13XMYC; TRP1 | This study |

| YAP1273 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 pMT634 | This study |

| YAP1275 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3 pMT634 | This study |

| YAP1277 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 cdc34-2 pMT634 | This study |

| YAP1294 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB5-3XHA; TRP1 | This study |

| YAP1543 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB2-3XHA; TRP1 | This study |

| YAP1646 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 ASE1-3XHA; TRP1 | This study |

| YAP1949 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 pAP62 | This study |

| YAP1951 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3 pAP62 | This study |

| YAP1955 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 apc11Δ::HIS3 leu2Δ1::apc11-13 pAP62 | This study |

| YAP2004 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CDC5-3XHA; TRP1 | This study |

| YAP2305 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 mnd2Δ::KanMX pOCF30 | This study |

| YAP2307 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 mnd2Δ::KanMX pAP62 | This study |

| YAP2340 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| YAP2343 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| YAP2346 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 pOCF30 | This study |

| YAP2410 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB2-3XHA; TRP1 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| YAP2419 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB2-3XHA; TRP1 mnd2Δ::KanMX | This study |

| YAP2428 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 mad2Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| YAP2432 | MATα his3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 mad2Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| YAP2441 | MATα his3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 bub2Δ::TPR1 | This study |

| YAP2443 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 bub2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| YAP2481 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 apc1-21; trp1Δ::HIS3 pOCF30 | This study |

| YAP2485 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 apc1-21; trp1Δ::HIS3 pAP62 | This study |

| YAP2771 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 apc9Δ::TRP1 pOCF30 | This study |

| YAP2775 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 cdc26Δ::TRP1 pOCF30 | This study |

| YAP2821 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 PDS1-13XMYC; TRP1 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| YAP2824 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 PDS1-13XMYC; TRP1 mnd2Δ::KanMX | This study |

| YAP2827 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB5-3XHA; TRP1 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| YAP2830 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB5-3XHA; TRP1 mnd2Δ::KanMX | This study |

| YAP2861 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 ASE1-3XHA; TRP1 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| YAP2864 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CDC5-3XHA; TRP1 swmΔ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| YAP2873 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB5-3XHA; TRP1 swm1Δ::HIS3MX6 pds1Δ::KanMX | This study |

| YAP2934 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB2-3XHA; TRP1 apc9Δ::KanMX | This study |

| YAP2937 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 PDS1-13XMYC; TRP1 apc9Δ::KanMX | This study |

| YAP2941 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 CLB5-3XHA; TRP1 apc9Δ::KanMX | This study |

| YVA387 | MATα his3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 mad2Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| YVA388 | MATα his3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 mad2Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| YVA389 | MATα his3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 bub2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| YVA390 | MATα his3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 bub2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| YVA1048 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 apc1-21; TRP1 | This study |

| YVA1098 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 apc1-21; trp1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| YVA1114 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 mnd2Δ::KanMX | This study |

| YVA1130 | MATahis3-Δ200 ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 trp1Δ63 MND2-13XMYC; TRP1 | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pMT634 | pGAL1-CLN2-HA URA3 LEU2 CEN | M. Tyers |

| pSG2 | pRS424-SWM1 | S. Givan |

| pVA117 | pRS426-MND2 | This study |

| pOCF30 | pRS416-GAL1-PDS1 | D. Koshland |

| pAP62 | pRS414-GAL1-ASE1-3XMYC | This study, derived from pPB338 from D. Pellman |

Galactose shutoff assays:

Cells were grown to midlog phase at the permissive temperature (25° or 30°) in SC media lacking uracil, tryptophan, or leucine, with 2% raffinose, supplemented with an additional 1× adenine, uracil, and/or tryptophan as appropriate. After washing cells twice with ddH2O, cells were resuspended in the same media and arrested in α-factor for ∼3.5 hr or until >90% of cells had mating projections. Following α-factor arrest, cultures were standardized to similar densities. For experiments conducted at temperatures higher than the arrest temperature, cultures were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature for 15 min before being induced with 2% galactose for 30 min. After galactose induction, glucose was added to 2% and cycloheximide to 1 mg/ml to repress transcription and translation from the GAL1 promoter. For each time point, volume-adjusted aliquots were removed from the culture, immersed in 1× ice-cold SC-Ura-Trp with no carbon source and rapidly centrifuged. Cell pellets were washed with 1 ml ice-cold ddH2O and transferred to Eppendorf tubes. After recentrifugation, cell pellets were immediately frozen at −70°.

Flow cytometry:

Typically 1 ml of midlog-phase cell culture was harvested for analysis. For cultures grown in synthetic complete media, 5–10 μl of 10 mg/ml bovine serum albumen (NEB) was often added to assist initial centrifugation of cells. Cell pellets were washed with 1 ml ice-cold 0.2 m Tris pH 7.5 and then resuspended in 70% ethanol in 0.2 m Tris pH 7.5 and fixed overnight at 4°. Fixed cells were treated with 1 mg/ml RNAse 0.2 m Tris pH 7.5 for ∼4 hr at 37° and were then incubated overnight at 50° after addition of 5–10 μl of 20 mg/ml Proteinase K. Cells were stained overnight in 5 μg/ml propidium iodide in 0.2 m Tris pH 7.5 at 4° and were lightly sonicated before analysis on a Becton Dickinson FACSSort.

Cell cycle arrest-release experiments:

We constructed strains containing APC/C substrates epitope tagged on the carboxy terminus with either 3XHA or 13XMYC in wild-type, swm1Δ, mnd2Δ, or apc9Δ backgrounds. Cultures were grown in YPD to midlog phase at 25°, harvested, and washed twice with ddH2O. Cells were then resuspended in YPD with 1× α-factor and arrested for ∼2 hr or until >90% of cells had mating projections. Cultures were reharvested and washed twice with ddH2O and then resuspended in YPD and released into the cell cycle at 25° after standardizing for culture density. At 15-min intervals, 1 ml of culture was harvested for protein pellets and 1 ml was harvested for FACS analysis.

Protein extracts and Western blot analysis:

Except for immunoprecipitations, whole-cell lysate was prepared by the method described in Goh et al. (2000). Typically, 20–40 μl/sample were loaded on SDS-PAGE gels. When using the wet transfer method, we transferred to PVDF for 4–5 hr at 750 mA, whereas when using the semidry method we transferred to nitrocellulose for 1 hr at 12 V. Immunoblot analysis was typically conducted as follows: Membranes were preblocked for 30 min in block buffer (5% milk/1× Tris-buffered saline TBS/0.05% Tween-200, followed by incubation with the primary antibody overnight in the same buffer. Blots were washed with wash buffer (1× TBS/0.05% Tween-20, supplemented with up to 0.1% SDS). Membranes were typically incubated with secondary antibody in block buffer for 4 hr at room temperature, followed by extensive washing with wash buffer prior to development.

Immunoprecipitations:

Glass-bead lysate was prepared as follows from log-phase cultures grown in YPD. Typically 250–500 ml of midlog-phase culture were harvested by centrifugation at 4° and resuspended in 3.5 ml extract buffer (50 mm Tris pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, supplemented with 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.7 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm PMSF, or with a EDTA-free complete protein inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche). A volume of glass beads approximately equal to the volume of cells harvested was added and cells were subjected to 16 cycles of vortexing by hand for 30 sec followed by a 30-sec incubation on ice. After centrifugation for 10 min at 4° at 13,000 rpm in a JA-20 rotor (Beckman, Fullerton, CA), lysate was transferred to Eppendorf tubes and cleared for 5–10 min at 14,000 rpm at 4° in an Eppendorf centrifuge. Cleared lysate was transferred to Eppendorf tubes, to which were added 50–100 μl of anti-myc conjugated beads (Covance). Immunoprecipitations were conducted overnight at 4° on an end-over-end rocker. The beads were pelleted in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 2000 rpm with tubes rotated 180° between spins to enhance pelleting. After removal of the supernatant, beads were washed five times in 1 ml ice-cold extract buffer, with each wash comprising 3 min of agitation on the end-over-end rocker, followed by the same centrifugation regimen. After the final wash, 250–300 μl of 2× Laemmli lacking β-mercaptoethanol was added to the bead pellet, which was then incubated at 42° for 5–10 min. The beads were then transferred to an NA-45 spin column and spun at −7500 rpm for 5 min, followed by addition of β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were boiled for 3 min and then immediately frozen at −70°. Antibodies against Cdc16p, Cdc27p, and Cdc23p are described in Lamb et al. (1994).

Immunofluorescence:

Cells were fixed for 90 min with one-tenth volume 37% formaldehyde at 37°, washed one to two times in 1 ml SK (1 m sorbitol, 50 mm KPO4 pH 7.5) and resuspended in SK. Cells were stained for microtubules with rat antitubulin (Yol 1/34) and fluorescein-conjugated goat-anti-rat. (GAN-F).

Anti-Apc2p antibodies:

A 348-bp BamHI-KpnI fragment (amino acids 1062–1410 of the APC2 open reading frame) was subcloned into pRSETB and expressed in bacteria. The resulting 6-HIS fusion protein was purified over a Ni + 2 column and injected into rabbits to produce polyclonal antibodies (Covance).

RESULTS

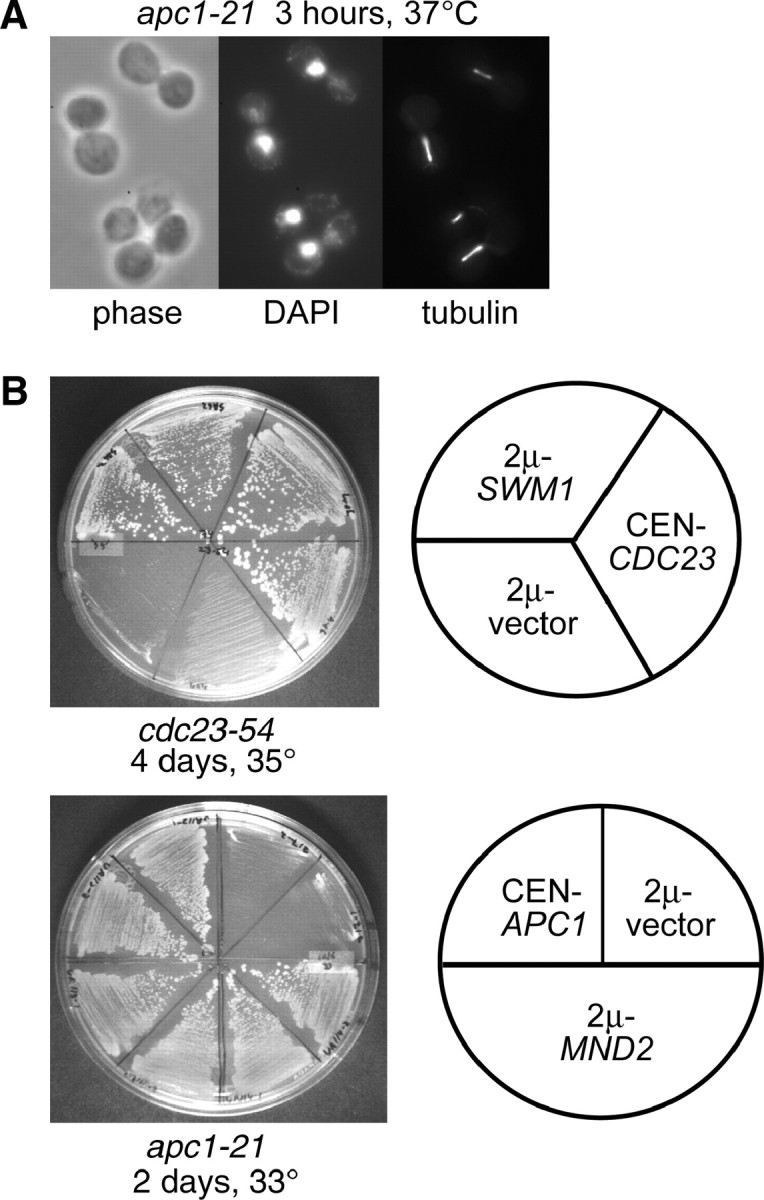

Identification of SWM1 and MND2:

To identify new components and regulators of the budding yeast anaphase-promoting complex, we conducted screens for high-copy suppressors of several temperature-sensitive mutants in previously identified APC/C components. In separate multi-copy suppression screens we identified SWM1 as a dosage suppressor of cdc23-54 and MND2 as a dosage suppressor of apc1-21. cdc23-54 is a previously described allele of CDC23 (Sikorski et al. 1993) whereas apc1-21 is a new allele of APC1 constructed by PCR mutagenesis. Upon shift to 37°, apc1-21 predominantly arrests as large-budded cells with short mitotic spindles and DAPI-staining masses at the bud neck, an arrest similar to other temperature-sensitive mutants in essential APC/C components (Figure 1A). apc1-21 mutants are also defective in APC/C substrate proteolysis in α-factor-arrested cells (see Figure 3). A 2μ plasmid containing SWM1 (pSG2) suppressed the temperature sensitivity of cdc23-54 at 35°, and a 2μ plasmid containing MND2 (pVA117) suppressed the temperature sensitivity of apc1-21 at 33° (Figure 1B). Consistent with previous reports describing the biochemical identification of Swm1p and Mnd2p in APC/C complexes (Yoon et al. 2002; Hall et al. 2003; Schwickart et al. 2004), both Swm1p-13XMYC and Mnd2p-13XMYC immunoprecipitated other APC/C subunits (see supplemental Figure S1, A and B, at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

Figure 1.—

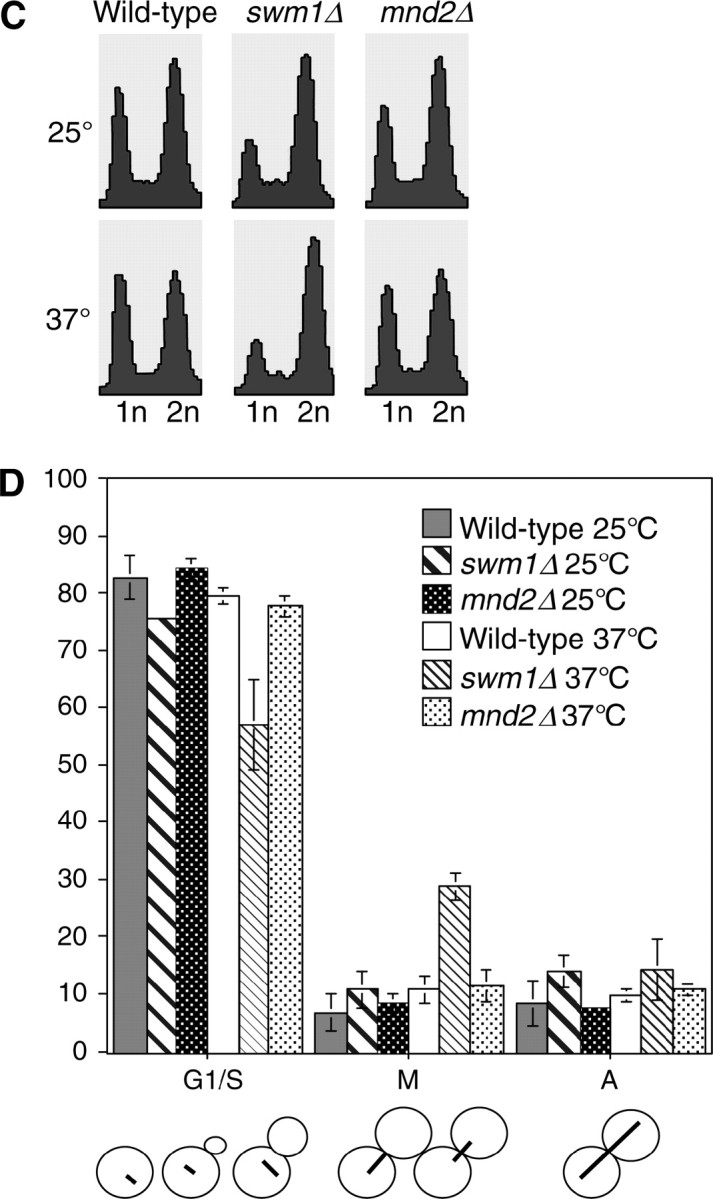

Identification of SWM1 and MND2 as new budding yeast APC/C components. (A) Terminal arrest phenotype of apc1-21. Upon shift to 37° for 3 hr, the majority of apc1-21 cells (YVA1098) arrest with large buds, short mitotic spindles, and DAPI-staining masses at or near the bud neck. (B) SWM1 and MND2 were identified as multicopy suppressors of cdc23-54 and apc1-21, respectively, in independent suppressor screens. A 2μ vector containing the SWM1 open reading frame suppresses the temperature sensitivity of cdc23-54 (YST74) at 35° and a 2μ vector containing MND2 suppresses the temperature sensitivity of apc1-21 (YVA1048) at 33°. (C) Flow cytometry analysis. A wild-type strain (YPH499), swm1Δ (YAP2340), and mnd2Δ (YVA1114) were cultured at 25° and shifted to 37° for 3 hr. Aliquots were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry or fixed and stained with antitubulin (Yol 1/34) and DAPI. At 25°, swm1Δ has a significant 2N accumulation, whereas the profile of mnd2Δ is similar to that of wild type. Upon shift to 37° for 3 hr, the 2N accumulation of swm1Δ, but not mnd2Δ, is further exacerbated. (D) Upon shift to 37°, the number of large-budded cells with short mitotic spindles at or near the bud neck is approximately threefold higher in swm1Δ compared to wild type.

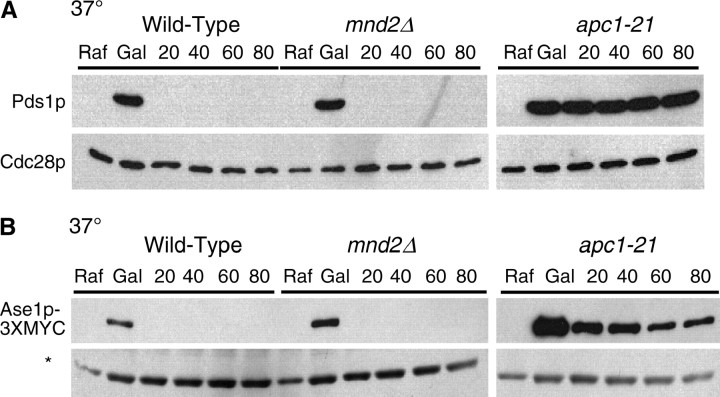

Figure 3.—

Mnd2p is dispensable for APC/C activity in α-factor-arrested cells. (A) Wild-type (YAP1146), mnd2Δ (YAP2305), and apc1-21 (YAP2841) strains containing pOCF30 were grown to midlog phase at 25° in SC-Ura 2% Raf media supplemented with additional adenine and tryptophan. Cultures were arrested at 25° with 5 μg/ml α-factor for 3.5 hr and then shifted to 37° for 15 min. Two percent galactose was added to induce PDS1 expression for 30 min at 37°. Two percent glucose and 1 mg/ml cycloheximide were then added to repress GAL1 transcription and translation, and aliquots for cell pellets and flow cytometry were harvested every 20 min and processed as in Figure 2A. (B) Wild-type (YAP1949), mnd2Δ (YAP2307), and apc1-21 (YAP2485) strains containing pAP62 were grown to midlog phase at 25° in SC-Trp 2% Raf media supplemented with additional uracil and adenine. Cultures were arrested with 5 μg/ml α-factor at 25° for 3 hr and 45 min and then shifted to 37° for 15 min. Cultures were induced with 2% galactose for 30 min at 37°, and then 2% glucose and 1 mg/ml cycloheximide was added to repress GAL1 transcription and translation. Aliquots for cell pellets and flow cytometry were harvested every 20 min and processed as in Figure 2A. The asterisk represents an unknown anti-Apc2p cross-reacting band used as a loading control.

swm1Δ and mnd2Δ deletion phenotypes:

Deletion of swm1Δ in the S288c background is viable from 25° to 35°, but swm1Δ strains grow poorly at 37°, arresting after one to five cell divisions. swm1Δ mutants grown at 25° in liquid culture are characterized by an accumulation in G2/M DNA content, which is exacerbated after shifting to 37° for 3 hr, whereas the FACS profile of mnd2Δ cultures does not significantly change (Figure 1C). In swm1Δ cultures at 37°, we typically observed a threefold increase in the number of large-budded cells with short mitotic spindles and DAPI-staining masses at the bud neck, whereas mnd2Δ strains did not accumulate large-budded cells with short spindles upon shift to 37° (Figure 1D). Prolonged incubation of swm1Δ cultures at 37° (up to 12 hr) does not cause significant loss of viability in swm1Δ mutants (data not shown). mnd2Δ mutants in the S288c background are not temperature sensitive at 37°. Levels of both Swm1p and Mnd2p proteins remained steady and did not fluctuate during the mitotic cell cycle (see supplemental Figure S2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

Swm1p but not Mnd2p is required for efficient turnover of specific APC/C substrates:

To assess the role of Swm1p and Mnd2p in APC/C substrate turnover, we monitored the degradation of several APC/C substrates in α-factor-arrested cells, where the APC/C is constitutively active against its known substrates (Amon et al. 1994; Irniger and Nasmyth 1997; Juang et al. 1997; Charles et al. 1998). We expressed Pds1p or Ase1p-3XMYC from the GAL1 promoter in cells arrested in G1 with α-factor and then repressed protein expression with the addition of glucose and cycloheximide. Both swm1Δ and mnd2Δ mutants arrest normally in α-factor and do not break through into S-phase. Maintenance of G1 arrest was verified by FACS analysis in all experiments (data not shown). In wild-type strains, both Pds1p and Ase1p-3XMYC are nearly undetectable 15–20 min after repression of their expression (Figure 2, A and B). In contrast, in swm1Δ the accumulated Pds1p persisted throughout the duration of the 60-min chase period, similar to the positive control, apc11-13, with little degradation in either strain. For Ase1p-3XMYC, in both swm1Δ and apc11-13, Ase1p-3XMYC accumulated to higher levels than in wild type, but its level decreased slowly over the course of the chase period. In our assays we observed only partial stabilization of ectopically expressed Ase1p-3XMYC, consistent with the observations of Thornton and Toczyski (2003) who reported incomplete stabilization of Ase1p in Apc− strains and proposed the possibility of an APC/C-independent pathway for Ase1p degradation. At 30°, swm1Δ mutants exhibited a similar failure to degrade Pds1p, with a significant portion of the protein still remaining at the 60-min time point (Figure 2C; see also Figure 4).

Figure 2.—

Swm1p is required for APC/C activity in α-factor-arrested cells. (A) Pds1p wild-type (YAP1146), swm1Δ (YAP1148), or apc11-13 (YAP645) strains bearing pOCF30 (pRS416-GAL1-PDS1) were cultured to midlog phase at 25° in SC-Ura 2% Raf supplemented with additional adenine and tryptophan and arrested for 3.5 hr with 5 μg/ml α-factor at 25°. Cultures were shifted to 37° for 15 min and then induced with 2% galactose for another 30 min at 37°. Two percent glucose and 1 mg/ml cycloheximide was added to repress transcription and translation of the GAL1 promoter, and aliquots were harvested for protein extracts and flow cytometry every 15 min. The “Raf” time point was harvested immediately before shift to 37° and the “Gal” time point was harvested immediately before addition of glucose and cycloheximide. Western blots were probed with anti-Pds1p (C210) and reprobed with anti-Cdc28p as a loading control. (B) Wild-type (YAP1949), swm1Δ (YAP1951), and apc11-13 (YAP1955) cultures all bearing pAP62 (pRS414-GAL1-ASE1-3XMYC) were cultured in SC-Trp 2% Raf supplemented with additional adenine and uracil and arrested as in A. Western blots were probed with anti-MYC (9E10). An anti-Apc2p (BC039) cross-reacting band is used as a loading control. The asterisk represents an unknown anti-Apc2p cross-reacting band used as a loading control. (C) Wild type (YAP1146) and swm1Δ (YAP1148) were cultured to midlog phase in SC-Ura 2% Raf supplemented with additional adenine and tryptophan at 30° and arrested with 5 μg/ml α-factor for 3.5 hr. Cultures were induced with 2% galactose for 30 min and 2% glucose and 1 mg/ml cycloheximide was added to repress GAL1 transcription and translation. Aliquots for cell pellets and flow cytometry were harvested every 15 min and processed as in A. (D) YAP1273 (wild type), YAP1275 (swm1Δ), and YAP1277 (cdc34-2), all bearing pMT634 (pGAL1-CLN2-HA), were grown to midlog phase in SC-Ura 2% Raf supplemented with extra adenine and tryptophan. Cultures were arrested for 3.5 hr in 0.1 m hydroxyurea at 25°, then 2% galactose was added, and cultures were shifted to 37° for 45 min. After galactose induction of Cln2p-3XHA, 2% glucose and 1 mg/ml cycloheximide were added to repress GAL1 transcription and translation and aliquots were harvested for cell pellets and flow cytometry every 15 min. The “Raf” time point was harvested immediately before galactose induction and shift to 37°. Whole-cell lysate was prepared as described in Goh et al. (2000). Western blots were probed with anti-HA (12CA5) and reprobed with anti-Cdc28p as a loading control.

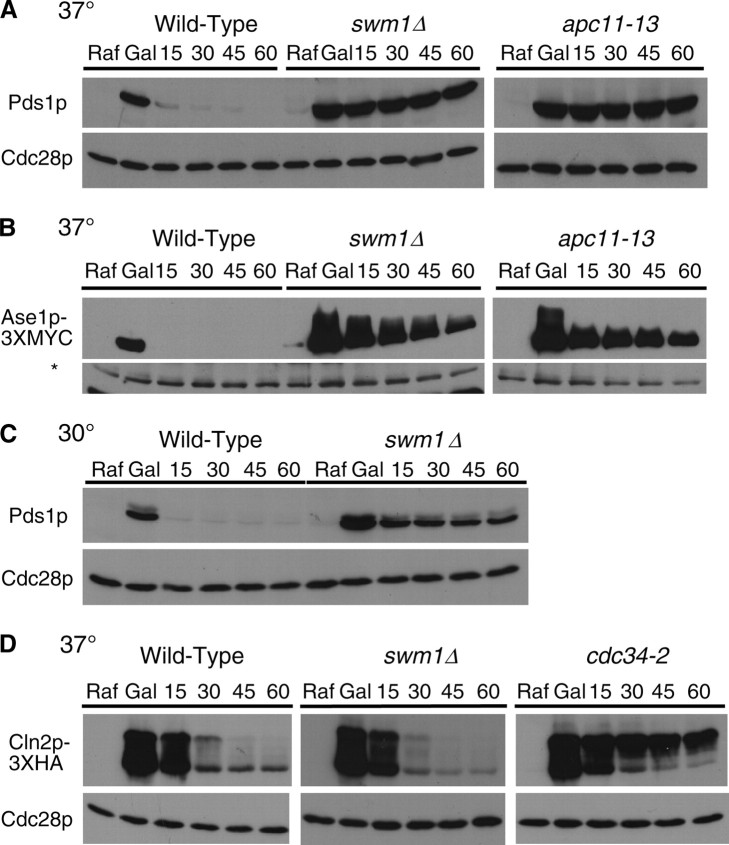

Figure 4.—

Deletions of SWM1, APC9, and CDC26 have substantially different APC/C activity in α-factor-arrested cells. (A) Wild-type (YAP1146), swm1Δ (YAP2346), apc9Δ (YAP2771), and cdc26Δ (YAP2775) strains bearing pOCF30 were grown to midlog phase at 25° in SC-Ura 2% Raf supplemented with additional tryptophan and adenine. Cells were arrested with 5 μg/ml α-factor at 25° for 3 hr and 45 min and then shifted to 30° for 15 min. Cultures were induced with 2% galactose for 30 min at 30° and then 2% glucose and 1 mg/ml cycloheximide was added to repress GAL1 transcription and translation. Maintenance of α-factor-arrested cells was verified by flow cytometry (data not shown). Western blots were probed with anti-Pds1p (C210, D. Koshland) and reprobed with anti-Cdc28p as a loading control. (B) Pds1p levels were quantified on a Bio-Rad (Richmond, CA) Fluor-S multi-imager.

To rule out a role for Swm1p in general ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, we assessed the role of Swm1p in the turnover of the G1 cyclin Cln2p. Cln2p degradation requires both SCFGrr1 and Cdc34p, an SCF-associated ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) (Deshaies et al. 1995; Willems et al. 1996; Kishi and Yamao 1998; Patton et al. 1998). Cln2p is unstable in hydroxyurea-arrested cells, when the APC/C is inactive against its known substrates (Willems et al. 1996). Wild-type, swm1Δ, and cdc34-2 cells were arrested in hydroxyurea and Cln2p-3XHA was expressed from the GAL1 promoter. Thirty minutes after repression of the GAL1 promoter, the bulk of Cln2p-3XHA was degraded in both wild type and swm1Δ, but persisted in cdc34-2 throughout the duration of the time course (Figure 2D). A β-galactosidase-ubiquitin-fusion construct, which is dependent on the N-end rule pathway for its proteolysis (Bachmair et al. 1986; Varshavsky 1996), was also rapidly degraded in a swm1Δ strain (data not shown). Collectively, our results suggest that Swm1p is specifically required for APC/C-dependent ubiquitination and is not required for general ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis.

In contrast to the APC/C substrate stabilization exhibited by swm1Δ, mnd2Δ mutants failed to stabilize either Pds1p (Figure 3A) or Ase1p-3XMYC (Figure 3B). Both substrates were rapidly degraded after 20 min to levels similar to that of the wild-type strain, whereas in an apc1-21 mutant, levels of both substrates persisted throughout the duration of the time course. Our results demonstrate that Swm1p, but not Mnd2p, is required for efficient APC/C function in α-factor-arrested cells.

In galactose shutoff experiments using Pds1p as an APC/C substrate, swm1Δ mutants consistently exhibited stabilization of ∼50–70% of the initially expressed Pds1p protein. This stabilization was not temperature dependent as we observed this phenomenon at both the permissive temperature for swm1Δ growth (30°) and the nonpermissive temperature (37°). To ascertain whether other nonessential APC/C subunits exhibit this phenomenon, we conducted similar experiments in apc9Δ and cdc26Δ. In the S288c background, apc9Δ mutants are viable at 37°, whereas cdc26Δ mutants grow normally at 30° but fail to grow at 33° and above. In galactose shutoff assays conducted at 30°, we observed substantial differences in the degradation pattern of Pds1p among swm1Δ, cdc26Δ, and apc9Δ mutants (Figure 4A). From quantification of the amount of Pds1p in the “Gal” time point of each strain in several experiments, we estimate that, in swm1Δ and cdc26Δ, the starting amount of Pds1p is approximately twofold greater than the amount of Pds1p in the wild-type strain or apc9Δ. For both swm1Δ and apc9Δ, after an initial drop in Pds1p levels, a fraction of Pds1p remains undegraded for the duration of the time course. Compared to the swm1Δ mutant, in which a substantial portion of Pds1p remains undegraded after 60 min, in the apc9Δ mutant only a small fraction of Pds1p is refractory to degradation during the entire time course. Similar to swm1Δ, in the cdc26Δ mutant, Pds1p accumulates to higher levels than in the wild-type strain, but its levels diminish gradually over the course of the experiment (Figure 4B). Our results demonstrate that, at permissive temperatures, nonessential APC/C subunits exhibit substantial differences in the degradation of ectopically expressed Pds1p and that the contribution of each subunit to overall APC/C activity varies significantly.

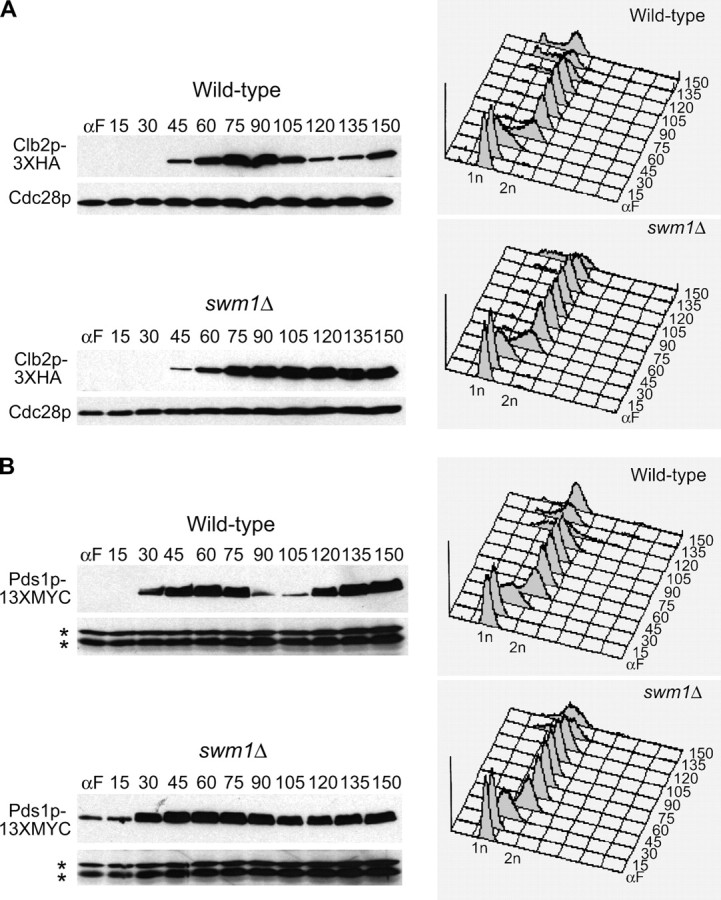

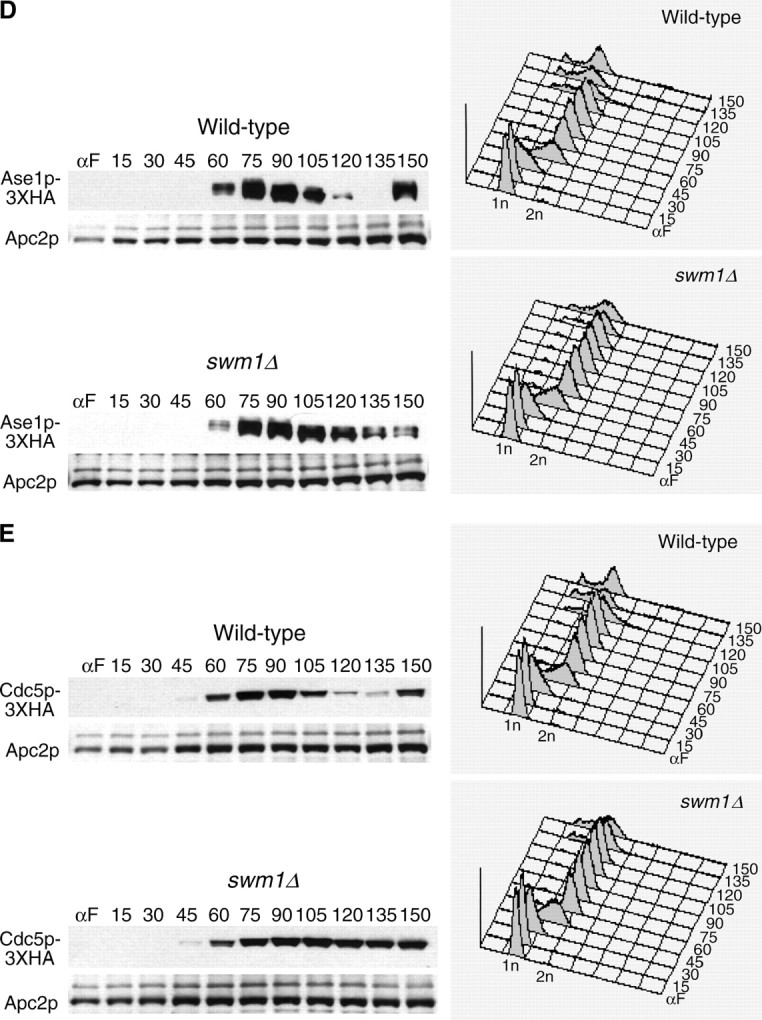

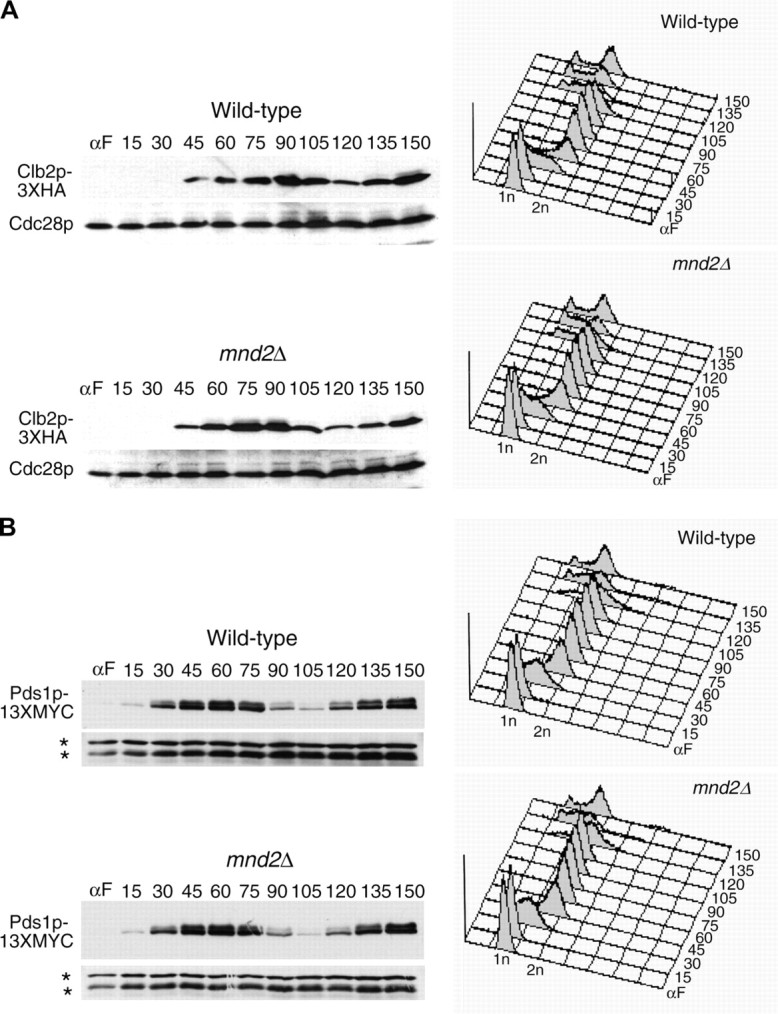

swm1Δ mutants but not mnd2Δ mutants exhibit defects in APC/C substrate degradation through the cell cycle:

APC/CCdc20p activity is required for the timely degradation of Pds1p, Clb5p, and a fraction of the total pool of Clb2p (Goh et al. 2000; Irniger 2002), and in strains where Clb2p is degradable by APC/CCdh1p, deletion of both CLB5 and PDS1 makes Cdc20p dispensable for cellular viability (Shirayama et al. 1999; Wasch and Cross 2002; Thornton and Toczyski 2003). Having demonstrated a requirement for Swm1p, but not for Mnd2p, for full APC/C activity against ectopically expressed substrates in α-factor-arrested cells, we next examined whether strains lacking either Swm1p or Mnd2p are defective in APC/C proteolysis of tagged substrates expressed from their endogenous promoters over the course of the cell cycle. In both the wild-type strain and swm1Δ, Clb2p-3XHA appeared 45 min after release from α-factor. In the wild-type strain, Clb2p-3XHA levels declined 105 min after release as the cells entered anaphase, but in swm1Δ, Clb2p-3XHA levels remained high throughout the time course with no degradation (Figure 5A). For Pds1p-13XMYC, we observed initial accumulation of Pds1p-13XMYC protein 30 min after release from α-factor in wild type and initiation of Pds1p-13XMYC turnover at ∼90 min, with the bulk of Pds1p-13XMYC protein having been degraded by 105 min. In swm1Δ however, Pds1p-13XMYC levels decline only slightly during the onset of anaphase, with substantial levels persisting at 90 and 105 min. Furthermore, we consistently observed undegraded Pds1p-13XMYC in α-factor-arrested cells and at the 15-min time point (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.—

Deletion of SWM1 affects APC/C substrate turnover during the mitotic cell cycle. (A) swm1Δ is defective in Clb2p-3XHA degradation at the permissive temperature. Wild-type (YAP1543) and swm1Δ (YAP2410) strains containing CLB2-3XHA were grown to midlog phase in 50 ml YEPD, washed twice with ddH2O, and resuspended in 50 ml YEPD with 5 μg/ml α-factor. Cultures were arrested for 135–150 min at 30°, with a booster dose of 3.75 μg/mLl α-factor added after 90 min. Cells were then harvested and washed twice with ddH2O and resuspended in 30 ml YEPD lacking α-factor. Cultures were standardized to similar density and released into the cell cycle at 25°. Every 15 min, 1 ml of each culture was harvested for cell pellets and 1 ml was harvested for flow cytometry. Cell pellet aliquots were washed with 1 ml ice-cold ddH2O and immediately frozen at −80° until extracts were prepared. Whole-cell lysate was prepared as described in Goh et al. (2000). Western blots were probed with anti-HA (12CA5) and reprobed with anti-Cdc28p as a loading control. (B) Pds1p-13XMYC is partially stabilized in swm1Δ. Wild-type (YAP1232) and swm1Δ (YAP2821) strains containing PDS1-13XMYC were arrested and released into the cell cycle as in A. Western blots were probed with anti-MYC (9E10) and reprobed with anti-Cdc28p. The asterisks represent anti-Cdc28p cross-reacting bands used as a loading control. (C) Delay of Clb5p-3XHA degradation in swm1Δ does not depend on Pds1p. Wild-type (YAP1294), swm1Δ (YAP2827), and swm1Δ pds1Δ (YAP2873) strains containing CLB5-3XHA were arrested and released into the cell cycle as described in A. (D) Ase1p-3XHA is partially stabilized in swm1Δ. Wild-type (YAP1646) and swm1Δ (YAP2861) strains containing ASE1-3XHA were arrested and released into the cell cycle as described in A. (E) Cdc5p-3XHA degradation is defective in swm1Δ. Wild type (YAP2004) and swm1Δ (YAP2864), both containing CDC5-3XHA, were arrested and released into the cell cycle as described in A.

In the case of Clb5p, we observed significant accumulation of Clb5p-3XHA protein 15 min after release from α-factor in both wild type and swm1Δ. In the wild-type strain, Clb5p-3XHA levels began to decline 75 min after release from α-factor and reached their lowest level at 90 min. In swm1Δ strains, onset of Clb5p-3XHA degradation was delayed by ∼15 min with the Clb5p-3XHA reaching its lowest level at 105 min. The delay in Clb5p-3XHA degradation was not due to the failure of swm1Δ to efficiently degrade Pds1p as the timing of Clb5p-3XHA proteolysis was still delayed by 15 min in the swm1Δ pds1Δ double mutant (Figure 5C).

We also tested the requirement of Swm1p in the degradation of two APC/CCdh1p substrates, Cdc5p-3XHA and Ase1p-3XHA. Like Clb2p, in the swm1Δ mutant Cdc5p-3XHA levels remained steadily high throughout the cell cycle (Figure 5E), whereas Ase1p-3XHA exhibited a proteolysis defect but was not completely stabilized (Figure 5D). Our results demonstrate that Swm1p is required for the timely degradation of both APC/CCdc20p and APC/CCdh1p substrates and that swm1Δ mutants exhibit significant proteolysis defects even at permissive temperatures.

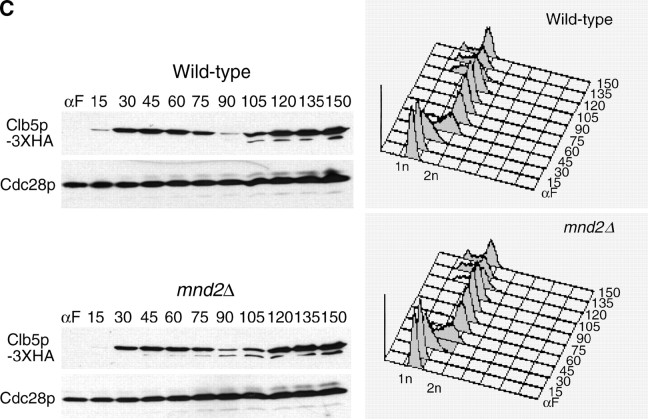

We conducted similar experiments to assess the timing of APC/C substrate degradation in mnd2Δ mutants. In contrast to swm1Δ, we did not observe any significant differences in the timing of onset of Clb2p-3XHA (Figure 6A), Pds1p-13XMYC (Figure 6B), and Clb5p-3XHA (Figure 6C) degradation. These results are consistent with our failure to observe stabilization of ectopically expressed APC/C substrates in α-factor-arrested mnd2Δ cultures and suggest that Mnd2p is largely dispensable for APC/C substrate proteolysis in the absence of other APC/C defects.

Figure 6.—

Deletion of MND2 does not affect degradation of APC/C substrates during the mitotic cell cycle. CLB2-3XHA (YAP1543) and CLB2-3XHA mnd2Δ (YAP2419) (A), PDS1-13XMYC (YAP1232) and PDS1-13XMYC mnd2Δ (YAP2824) (B), and CLB5-3XHA (YAP1294) and CLB5-3XHA mnd2Δ (YAP2830) (C) were arrested with α-factor and released into the cell cycle as described in Figure 5A. Deletion of MND2 did not substantially affect the timing of Clb2p-3XHA, Pds1p-13XMYC, or Clb5p-3XHA degradation. Asterisks in B represent anti-Cdc28p cross-reacting bands used as a loading control.

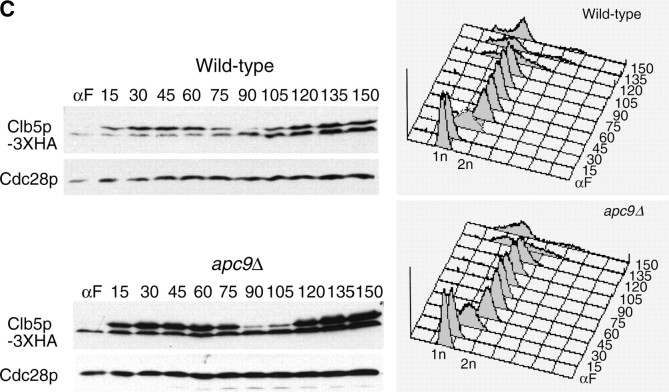

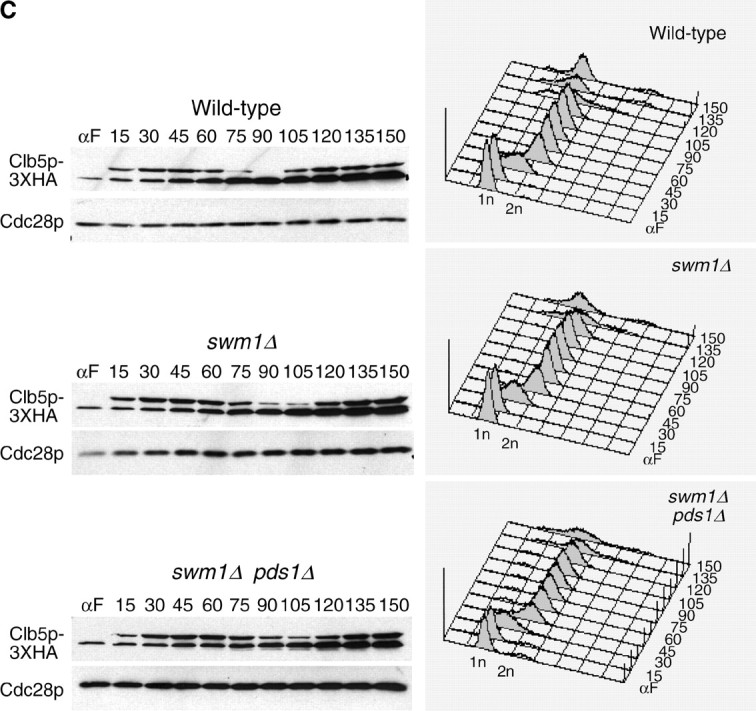

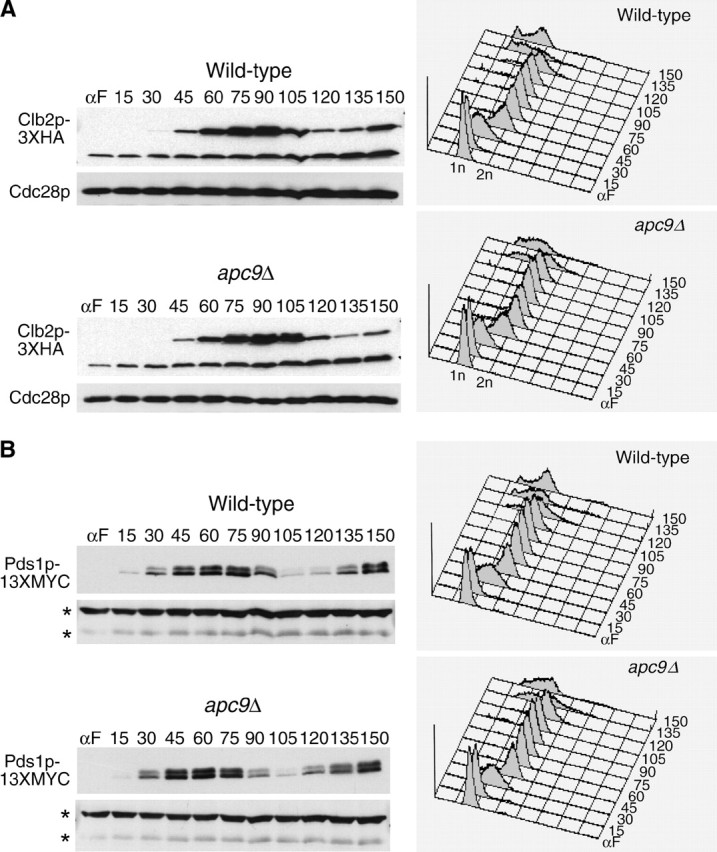

Timing of Clb2p but not Pds1p or Clb5p degradation is delayed in apc9Δ mutants:

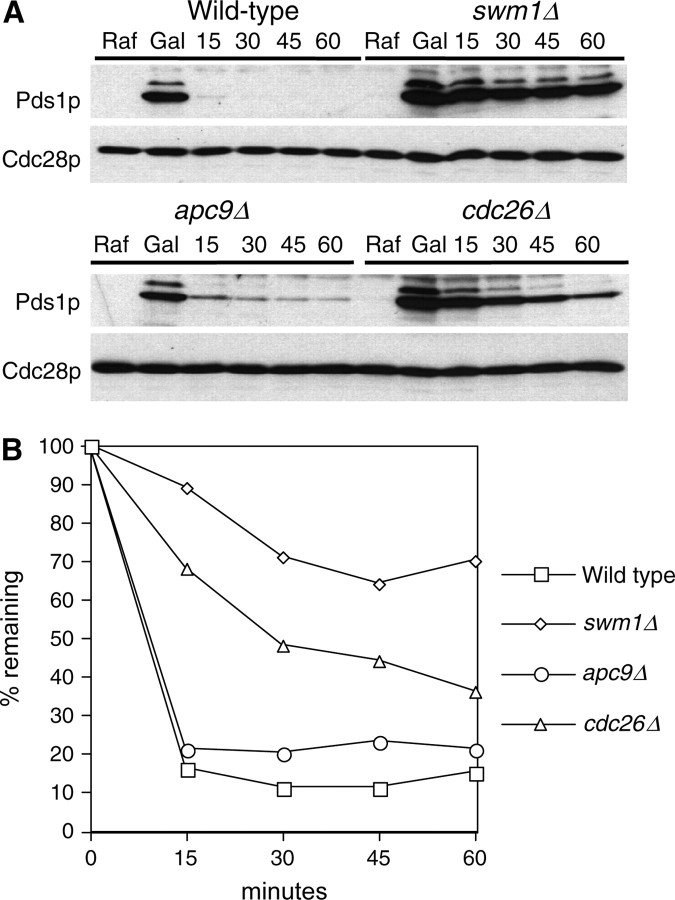

Given our failure to observe significant stabilization of ectopically expressed Pds1p in apc9Δ cultures arrested in α-factor, we assessed the timing of APC/C substrate degradation in apc9Δ over the mitotic cell cycle. Onset of Clb2-3XHA degradation (Figure 7A) was consistently delayed 15 min in apc9Δ, but the amount of Clb2p-3XHA eventually declined to the same level as that in the wild-type strain. In contrast, the timing of Pds1p-13MYC and Clb5p-3XHA degradation in apc9Δ was nearly identical to that of wild type, with the disappearance of both proteins occurring by 105 min (Figure 7, B and C). Our findings suggest that the requirement for Apc9p in APC/C function may be limited to the degradation of only some APC/C substrates and not others. Alternatively, APC/C complexes lacking Apc9p may retain sufficient activity to degrade Pds1p and Clb5p efficiently, but not Clb2p.

Figure 7.—

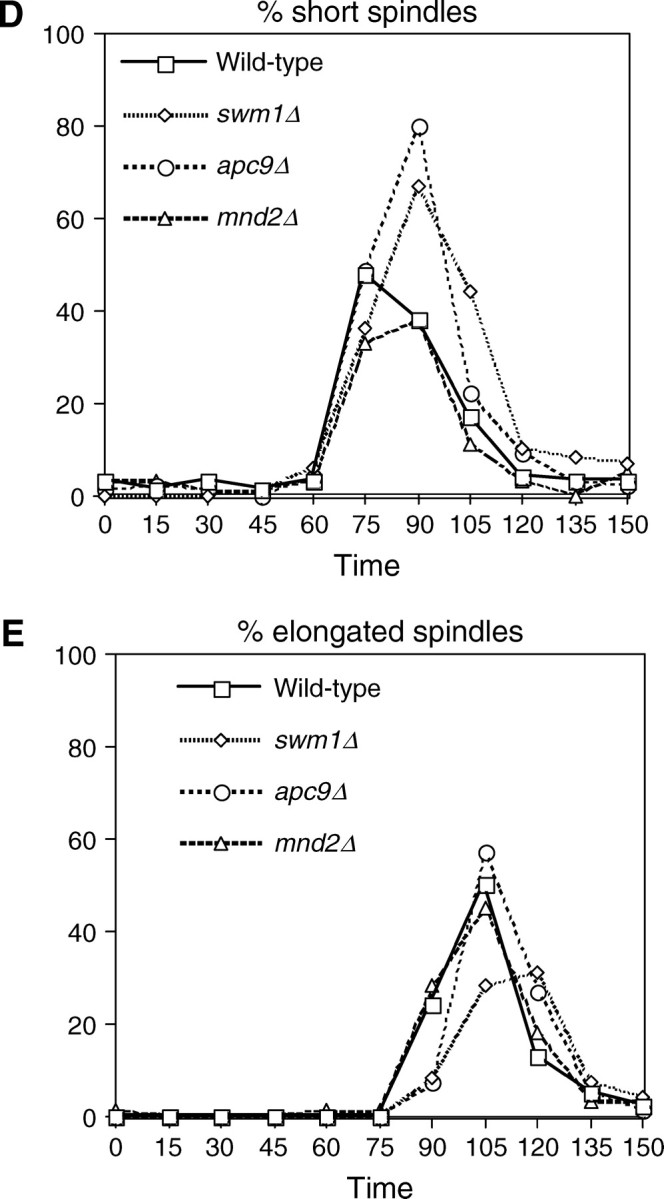

APC/C substrate degradation in apc9Δ. CLB2-3XHA (YAP1543) and CLB2-3XHA apc9Δ (YAP2934) (A), PDS1-13XMYC (YAP1232) and PDS1-13XMYC apc9Δ (YAP2937) (B), and CLB5-3XHA and CLB5-3XHA apc9Δ (YAP2941) (C) were arrested with α-factor and released into the cell cycle as described in Figure 5A. apc9Δ delayed the onset of Clb2p-3XHA proteolysis but did not significantly affect the timing of PDS1-13XMYC and Clb5p-3XHA degradation. Asterisks in B represent anti-Cdc28p cross-reacting bands. (D and E) Wild-type (YPH499), swm1Δ (YAP2340), apc9Δ (YAP2930), and mnd2Δ (YVA1114) were grown to midlog phase in YEPD, arrested with α-factor, and released into the cell cycle as described in Figure 5A. Samples were harvested and fixed for immunofluorescence and stained with antitubulin (Yol 1/34) and DAPI. Short and long mitotic spindles were scored for each time point (n = 100).

Spindle elongation is delayed in swm1Δ and apc9Δ mutants:

In our arrest-release experiments, we consistently observed in swm1Δ, and to a lesser extent in apc9Δ, a delay in reaccumulation of 1N content in FACS profiles. Typically 1N content began to reappear at 120 min in wild-type and mnd2Δ strains but not until 135 min in swm1Δ and apc9Δ. To ascertain whether any of these mutants are delayed in early or late anaphase, we arrested cultures in α-factor, as in Figure 2, and released them into the mitotic cell cycle at 25°. In swm1Δ and apc9Δ, accumulation of short spindles (75–105 min) was delayed by ∼15 min compared to wild-type and mnd2Δ. By 105 min, the number of short spindles in apc9Δ was comparable to that of wild type and mnd2Δ, but in swm1Δ a significant number of cells had short spindles at 120 min (Figure 7D). Likewise, onset of spindle elongation (Figure 7E) occurred between 75 and 120 min for wild type and mnd2Δ and between 90 and 120 min for apc9Δ. In swm1Δ, appearance of elongated spindles was delayed by ∼15 min with the peak occurring at 105–120 min. These results are consistent with our observations that swm1Δ mutants are defective in the degradation of a broad spectrum of both APC/CCdc20p and APC/CCdh1p substrates, whereas apc9Δ mutants exhibit only a delay in the degradation of Clb2p and not Pds1p or Clb5p.

Genetic analysis of swm1Δ, mnd2Δ, and apc9Δ mutants:

We examined the genetic interactions of swm1Δ with mutations in other APC/C components and regulators (Table 2). swm1Δ exhibited synthetic lethality with null mutations, both for germination of spores and vegetative growth, in three other nonessential budding yeast APC/C subunits: apc9Δ, cdc26Δ, and doc1Δ. swm1Δ was also synthetically lethal with cdc23-1 and cdc23-54, as well as the CDC28-VF mutant, which reduces APC/C activity and has been shown to be synthetically lethal with other APC/C mutants (Rudner et al. 2000). In addition, we assessed the genetic interactions of swm1Δ with a deletion in either UBC4 or CLB2. Ubc4p is an E2-ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that can activate the APC/C in vitro (Charles et al. 1998) and ubc4Δ mutants have been shown to be synthetically lethal with the apc mutants cdc23-1 and doc1Δ (Irniger et al. 1995, 2000). In addition to being an APC/C substrate, Clb2p directs the phosphorylation of APC/C TPR subunits by its partner kinase Cdc28p (Rudner and Murray 2000), and clb2Δ is synthetically lethal with cdc23-1 (Irniger et al. 1995). Both swm1Δ ubc4Δ and swm1Δ clb2Δ double mutants were viable, but exhibited conditional synthetic lethality at 35°. Deletion of SWM1 did not exhibit a genetic interaction with clb5Δ. We also assessed genetic interactions between swm1Δ and the APC/C specificity factors. swm1Δ was synthetically lethal with the cdc20-1 mutation, but swm1Δ cdh1Δ double mutants were viable at temperatures up to 35°. Sic1p is a B-type cyclin inhibitor that acts in parallel with the APC/C to inhibit cyclin B-CDK activity at exit from mitosis (Mendenhall 1993; Donovan et al. 1994; Nugroho and Mendenhall 1994; Schwob et al. 1994). sic1Δ mutations are synthetically lethal with cdh1Δ mutations (Schwab et al. 1997; Shah et al. 2001; Cross 2003), as well as with temperature-sensitive mutations in CDC23 and APC2 (Schwab et al. 1997; Kramer et al. 1998). Crosses between sic1Δ and swm1Δ strains generated viable sic1Δ swm1Δ double mutants, although ∼40% of sic1Δ swm1Δ spores failed to germinate. Surviving sic1Δ swm1Δ double mutants were viable at 35°.

TABLE 2.

swm1Δ genetics

| Genotype | 25° | 30° | 33° | 35° | 37° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| swm1Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − |

| swm1Δ cdc23-54 | SL | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| swm1Δ cdc23-1 | SL | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| swm1Δ apc9Δ | SLa | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| swmΔ doc1Δ | SLa | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| swm1Δ cdc26Δ | SLa | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| swm1Δ cdc20-1 | SLa | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| swm1Δ ubc4Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | NA |

| swm1Δ CDC28-VF | SLa | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| swm1Δ cdh1Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | NA |

| swm1Δ sic1Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +/− | NA |

| swm1Δ mad2Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| swm1Δ bub2Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − |

| swm1Δ clb2Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | NA |

| swm1Δ clb5Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | NA |

SL, synthetic lethality; NA, not applicable.

Synthetic lethality for both spore germination and vegetative growth.

mnd2Δ mutants exhibited genetic interactions with a narrower spectrum of APC/C components and regulators than swm1Δ mutants (Table 2). mnd2Δ was synthetically lethal with apc1-21 and reduced the nonpermissive temperatures of cdc26Δ to 30° and doc1Δ to 35°, respectively. apc2-402 mnd2Δ double mutants grew somewhat slower at 33° than apc2-402 single mutants. However, mnd2Δ did not exhibit significant genetic interactions with swm1Δ, apc9Δ, ubc4Δ, cdh1Δ, and CDC28-VF and did not lower the nonpermissive temperature of cdc20-1 or apc11-13 (Table 3). These findings suggest either that the loss of Mnd2p is not particularly deleterious to APC/C function in general or that only a limited number of APC/C subunits depend on Mnd2p for their full activity.

TABLE 3.

mnd2Δ genetics

| Genotype | 25° | 30° | 33° | 35° | 37° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mnd2Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| mnd2Δ apc1-21 | SLa | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| mnd2Δ swm1Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ND |

| mnd2Δ apc9Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ND |

| mnd2Δ cdc26Δ | +++ | − | NA | NA | NA |

| mnd2Δ doc1Δ | +++ | ++ | + | − | NA |

| mnd2Δ apc2-402 | +++ | +++ | + | NA | NA |

| mnd2Δ apc11-13 | +++ | +++b | NA | NA | NA |

| mnd2Δ cdh1Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ND |

| mnd2Δ cdc20-1 | +++b | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| mnd2Δ ubc4Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ND |

| mnd2Δ CDC28-VF | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| mnd2Δ mad2Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| mnd2Δ bub2Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

SL, synthetic lethality; NA, not applicable. ND, not determined.

Synthetic lethality for both spore germination and vegetative growth.

Deletion of MND2 does not significantly lower the nonpermissive temperature of the single mutant.

apc9Δ mutations (Table 4) exhibited synthetic lethality with swm1Δ and cdc20-1 and conditional synthetic lethality with doc1Δ at 33°. However, we failed to observe genetic interactions among apc9Δ and ubc4Δ, cdh1Δ, and mnd2Δ. apc9Δ in combination with cdc26Δ was also viable and did not lower the nonpermissive temperature of the cdc26Δ single mutant. APC9 and SIC1 are somewhat closely linked (∼35 kb apart), but in crosses between sic1Δ and apc9Δ, we were able to recover a few haploid double-mutant spores that were viable at 35°.

TABLE 4.

apc9Δ genetics

| Genotype | 25° | 30° | 33° | 35° | 37° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| apc9Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| apc9Δ swm1Δ | SLa | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| apc9Δ mnd2Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ND |

| apc9Δ ubc4Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ND |

| apc9Δ doc1Δ | +++ | +++ | − | − | NA |

| apc9Δ cdc26Δ | +++ | +++ | − | − | NA |

| apc9Δ cdh1Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ND |

| apc9Δ cdc20-1 | SLa,b | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| apc9Δ sic1Δ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ND |

SL, synthetic lethality; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

Synthetic lethality for both spore germination and vegetative growth.

Some reversion/papillation was observed.

Deletion of mad2Δ partially suppresses the poor growth of swm1Δ:

We examined the genetic relationship of Swm1p and Mnd2p both to the spindle checkpoint, which inhibits APC/CCdc20p before the onset of anaphase in response to spindle damage or lack of microtubule attachment to kinetochores (Straight and Murray 1997; Skibbens and Hieter 1998; Shah and Cleveland 2000; Gorbsky 2001; Yu 2002), and to the mitotic exit checkpoint, which inhibits release of Cdc14p from the nucleolus and Cdh1p activation until the spindle is properly positioned (Li 1999; Bloecher et al. 2000; Pereira et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2000; Adames et al. 2001; Lew and Burke 2003). swm1Δ mutants respond normally to benomyl whereas mnd2Δ mutants are mildly sensitive (data not shown). Neither swm1Δ nor mnd2Δ strains exhibited elevated levels of loss of a nonessential chromosome fragment. swm1 mad2Δ and swm1Δ bub2Δ double mutants were viable at 35° (Table 2), and mnd2Δ mad2Δ and mnd2Δ bub2Δ mutants grew well at 37° (Table 3). Deletion of swm1Δ or mnd2Δ did not significantly affect the benomyl sensitivity of either mad2Δ or bub2Δ mutants. However, mad2Δ, but not bub2Δ, partially suppressed the poor growth phenotype of swm1Δ mutants at 37° (see supplemental Figure S3 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). This result suggests that the apc defect of swm1Δ mutants is partially relieved when the inhibitory effect of Mad2p on the APC/C is abrogated.

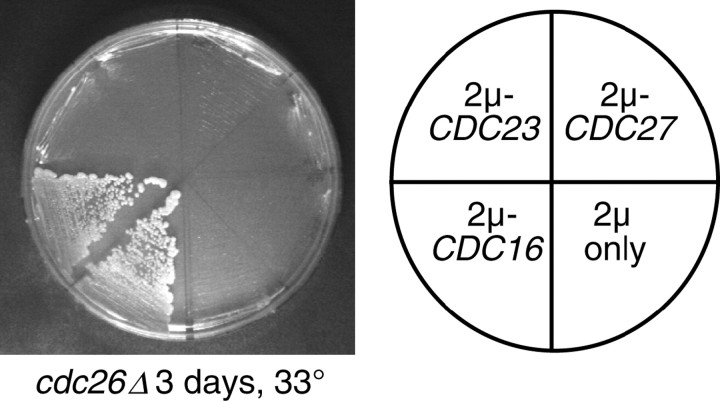

Overexpression of specific TPR proteins rescues the synthetic lethality of swm1Δ apc9Δ and swm1Δ cdc26Δ double mutants:

To better understand the nature of the lethal defects of swm1Δ apc9Δ and swm1Δ cdc26Δ double mutants, we examined whether overexpression of any of the three TPR proteins could rescue the inviability of either double mutant. The temperature sensitivity of cdc26Δ single mutants was rescued by a 2μ plasmid containing CDC16, but not CDC23, or CDC27 (Figure 8). Overexpression of APC2, APC11, CDC20, CDH1, APC5, APC9, APC1, or SWM1 likewise failed to rescue cdc26Δ (data not shown). We observed rescue of swm1Δ apc9Δ double mutants specifically by a 2μ plasmid carrying CDC27, but not CDC16 or CDC23, whereas only 2μ-CDC16 rescued swm1Δ cdc26Δ (Table 5). Loss of the wild-type SWM1 gene was confirmed by PCR and by the observation that swm1Δ apc9Δ 2μ-CDC27 and swm1Δ cdc26Δ 2μ-CDC16 strains grow poorly at 30°, which is a permissive temperature for all three single mutants (Table 5). In addition, the temperature sensitivity of apc9Δ cdc26Δ at 33° and 35° was rescued by overexpression of CDC16, but not CDC23, CDC27, or SWM1. Our findings show that the lethality of swm1Δ apc9Δ and swm1Δ cdc26Δ can be rescued by overexpression of specific TPR proteins.

Figure 8.—

Suppression of APC/C double mutants by overexpression of specific TPR proteins. Overexpression of CDC16 suppresses the temperature sensitivity of cdc26Δ. cdc26Δ::KanMX (YVA435) was transformed with 2μ plasmids expressing a single APC/C component or regulator or with empty vector only. Individual transformants were outgrown on selective media at 25° and then applied to selective media at the nonpermissive temperature.

DISCUSSION

In wild-type cells, the ubiquitin-ligase activity of the anaphase-promoting complex against B-type cyclins and Pds1p is essential for normal progression from metaphase to anaphase and into G1 of the next cell cycle. Nevertheless, a surprising number of APC/C subunits are not essential for cell viability in budding yeast under normal growth conditions, and their contribution to APC/C function in vivo thus far has been poorly characterized. In this work we have shown that swm1Δ, apc9Δ, and mnd2Δ each have different effects on the degradation of APC/C substrates. We identified Swm1p and Mnd2p as new components of the budding yeast APC/C by screening for multicopy suppressors of existing apc mutants. We have demonstrated that at permissive temperatures for budding yeast growth, Swm1p is required for full APC/C function both during the mitotic cell cycle and in G1 arrest. This result is consistent with previous reports that swm1Δ mutants exhibit defects in APC/C substrate proteolysis at nonpermissive temperatures (Schwickart et al. 2004; Ufano et al. 2004). In arrest-release experiments conducted at 25°, swm1Δ exhibited partial stabilization of Pds1p-13XMYC, compared to an almost complete failure to degrade Clb2p-3XHA. Onset of Clb5p-3XHA degradation was delayed by ∼15 min but Clb5p-3XHA levels eventually decreased to those similar to wild type. The delay in onset of Clb5p-3XHA degradation was not simply due to cell cycle delay resulting from failure to degrade Pds1p, as swm1Δ pds1Δ was still delayed in Clb5p-3XHA degradation. Our results indicate that loss of Swm1p does not affect the degradation of all APC/C substrates.

apc9Δ mutants exhibited less severe proteolysis defects than did swm1Δ mutants. In α-factor arrested cells, where APC/CCdh1p is active, only a small fraction of the initial pool of ectopically expressed Pds1p was stabilized in apc9Δ. In arrest-release experiments, the timing of Clb2p-3XHA was delayed 15 min and the kinetics of Pds1p-13XMYC and Clb5p-3XHA degradation were similar to those of wild type. Our results suggest that Apc9p is required in vivo either for only the full activity of a small fraction of APC/CCdh1p complexes or against a limited number of APC/C substrates. Alternatively, deletion of APC9 simply may not have substantial consequences for the physical integrity of the APC/C in vivo, leading to delay in the complete degradation of some substrates (Clb2p), but not others (Pds1p and Clb5p). Our data do not support the conclusions of Passmore et al. (2003) who reported that apc9Δ mutants are significantly defective in Pds1p ubiquitination and binding of recombinant Cdh1p to purified APC/C complexes in vitro. If APC/CCdh1p interactions are significantly disrupted by apc9Δ in vivo, we would have expected to see a much more dramatic stabilization of Pds1p in α-factor-arrested cells. Our conclusions are supported by the fact that apc9Δ mutants arrest normally in α-factor, in contrast to cdh1Δ mutants, which fail to arrest normally due to high cyclin B/CDK levels (Schwab et al. 1997). One interesting possibility is that the role of Apc9p may be primarily restricted to APC/CCdc20p-mediated proteolysis of the pool of Clb2p whose degradation occurs at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, but not the pool that is degraded by APC/CCdh1p upon exit from mitosis. In their study of yeast completely lacking APC/C function, Thornton and Toczyski (2003) reported that of all the essential APC/C subunits, cdc27Δ alone did not require deletion of PDS1 for viability, only abrogation of B-type cyclin activity by SIC1 overexpression and deletion of CLB5. In the context of this result, and given our failure to observe significant defects in Pds1p proteolysis in apc9Δ strains, our observation that overexpression of CDC27 (but not CDC16 or CDC23) rescues the synthetic lethality of apc9Δ swm1Δ is intriguing, suggesting that, in some APC/C complexes, Apc9p and Cdc27p may collaborate in the degradation of Clb2p but not Pds1p. The loss of Cdc27p from APC/C complexes isolated from apc9Δ strains supports this notion (Zachariae et al. 1998; Passmore et al. 2003). Deletion of PDS1, CLB2, or CLB5 alone failed to suppress the synthetic lethality of apc9Δ swm1Δ (data not shown), and it will be important to determine which combination of APC/C substrates must be deleted to restore the viability of apc double-mutant lethalities.

An emerging model of APC/C subunit function is that the TPR proteins serve as linkers that couple the specificity factors, bound to their substrates, to the APC/C's catalytic machinery. Vodermaier et al. (2003) were recently able to fractionate human APC/C into subcomplexes, one comprising APC1, APC2, APC4, APC5, and APC11, but lacking the four TPR proteins and APC10. This subcomplex was competent for the assembly of polyubiquitin chains, but not for the in vitro ubiquitination of securin. Two TPR proteins, APC7 and APC3 (CDC27), strongly bound the carboxy termini of CDH1 and CDC20, and APC3 was previously shown to bind the carboxy terminus of APC10. CDC20, CDH1, and DOC1 all share a conserved isoleucine arginine motif (Vodermaier et al. 2003) on their carboxy termini, suggesting that this motif is recognized directly by APC3/CDC27 (Wendt et al. 2001; Vodermaier et al. 2003). Consistent with these data, the phosphorylation of TPR proteins by Clb/CDK activity has been shown to enhance the binding of Cdc20p to the complex (Rudner and Murray 2000). In the context of this model, the available biochemical and genetic data increasingly suggest that Swm1p, Apc9p, and Cdc26p collaborate to stabilize the association of TPR/WD-40/substrate complexes to the APC/C core catalytic machinery. SWM1 is a dosage suppressor of cdc23-54, and the conditional synthetic lethality of swm1Δ ubc4Δ is suppressed by the overexpression of CDC23 and, to a lesser extent, CDC27. swm1Δ is synthetically lethal with both apc9Δ and cdc26Δ, and these synthetic lethalities can be rescued by overexpression of specific TPR proteins. TAP-APC/C complexes purified from strains lacking Cdc26p contain reduced levels of Cdc27p, Cdc16p, Cdc23p, and Apc9p (Zachariae et al. 1998; Schwickart et al. 2004), whereas complexes purified from apc9Δ strains contain reduced levels of Cdc27p (Zachariae et al. 1998; Passmore et al. 2003). Schwickart et al. (2004) further report that Swm1p is required for the efficient binding of Cdc16p, Cdc27p, and Apc9p and that in cdc23 mutants a subcomplex of Swm1p, Cdc16p, Cdc27p, and Apc9p fails to bind to other APC/C subunits. They conclude that Swm1p, Cdc26p, Cdc16p, Cdc27p, and Apc9p form a subcomplex whose association with the rest of the APC/C is Cdc23p dependent. It is important to note that in budding yeast all three TPR proteins are encoded by essential genes. If the function of Swm1p, Apc9p, and Cdc26p really is to enhance the binding of TPR proteins, then, given the fact that SWM1, CDC26, and APC9 are nonessential genes, it follows that the in vivo binding of TPR/WD-40/substrate complexes to the APC/C core catalytic complex is only partially disrupted in any of the single mutants or the cdc26Δ apc9Δ double mutant.

In contrast to our results for Swm1p and Apc9p, we did not observe a significant requirement for Mnd2p in APC/C-dependent proteolysis against any of the substrates that we examined. In cell cycle experiments, the timing of degradation of Pds1p-13XMYC, Clb2p-3XHA, and Clb5p-3XHA in mnd2Δ was not substantially different from that of wild-type strains, and both Pds1p and Ase1p-3XHA were rapidly degraded when expressed ectopically from the GAL1 promoter in α-factor-arrested cells. Our results are consistent with the lack of ubiquitination defects in mnd2Δ reported by Passmore et al. (2003). Given the lack of APC/C proteolysis defects in mnd2Δ, it is difficult to explain the genetic interactions of mnd2Δ mutants that we observe with apc1-21, cdc26Δ, and doc1Δ and the multicopy suppression of apc-21 by 2μ-MND2 overexpression. Mnd2p clearly associates with the APC/C in both vegetatively growing cells and cells arrested with α-factor, hydroxyurea, or nocodozole (Yoon et al. 2002; Hall et al. 2003), but it is unclear whether all APC/C complexes contain Mnd2p or whether it is a substoichiometric component. Immunodepletion of Mnd2p-13XMYC from glass-bead lysate depleted the majority of Cdc27p from the supernatant but not all of Cdc23p, Cdc16p, or Apc2p, suggesting the possibility that APC/C complexes lack Mnd2p. One formal possibility is that, in otherwise wild-type mitotic cells, the functional contribution of Mnd2p to overall APC/C activity is so minimal as to be undetectable within the limitations of our assays, but lack of Mnd2p exacerbates APC/C defects when the complex is further perturbed. This hypothesis is supported by the limited amount of existing data about Mnd2p and its Schizosaccharomyces pombe homolog Apc15p. Growth curve and flow cytometry experiments revealed that mnd2Δ stains grow slightly slower than wild type, but even when grown at 37° there is little increase in the 2N DNA content in mnd2Δ (Hall et al. 2003; this work). Deletion of S. pombe Apc15p is viable, but unlike budding yeast mnd2Δ, apc15Δ/apc15Δ mutants did not exhibit meiotic defects (Yoon et al. 2002). Consistent with our findings, apc15Δ is synthetically lethal with cut4-553, a temperature-sensitive mutant in the S. pombe Apc1p homolog (Yoon et al. 2002). Another hypothesis is that Mnd2p may play a limited role in promoting the initial assembly of APC/C complexes or in maintaining the stability or proper cellular localization of one or more APC/C subunits, a function that might be dispensable once the APC/C is fully assembled and activated. However, levels of Apc1p in mnd2Δ are not substantially different from those in wild-type cells, indicating that Mnd2p does not regulate overall Apc1p levels (V. Aneliunas, personal communication). In addition, Mnd2p may be required for the turnover of a limited subset of APC/C substrates whose proteolysis is not required for cell cycle progression under normal conditions, but whose persistence becomes deleterious when APC/C catalytic function is compromised by other mutants. Finally, it is possible that both Mnd2p and Apc1p may have as-of-yet-undiscovered functions unrelated to APC/C ubiquitination activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Doug Koshland, Dave Pellman, Ray Deshaies, Mike Tyers, Scott Givan, and Erica Johnson for providing reagents. Thanks go to Isabelle Pot and Daniel Kornitzer for critical reading of the manuscript and to members of the Hieter Lab, Topher Carroll, and Dave Morgan for helpful discussions. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant CA16569 to P.H.

References

- Adames, N. R., J. R. Oberle and J. A. Cooper, 2001. The surveillance mechanism of the spindle position checkpoint in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 153 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amon, A., 2001. Together until separin do us part. Nat. Cell Biol. 3 E12–E14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amon, A., S. Irniger and K. Nasmyth, 1994. Closing the cell cycle circle in yeast: G2 cyclin proteolysis initiated at mitosis persists until the activation of G1 cyclins in the next cycle. Cell 77 1037–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmair, A., D. Finley and A. Varshavsky, 1986. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science 234 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloecher, A., G. M. Venturi and K. Tatchell, 2000. Anaphase spindle position is monitored by the BUB2 checkpoint. Nat. Cell Biol. 2 556–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton, J. L., and M. J. Solomon, 2001. D box and KEN box motifs in budding yeast Hsl1p are required for APC-mediated degradation and direct binding to Cdc20p and Cdh1p. Genes Dev. 15 2381–2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles, J. F., S. L. Jaspersen, R. L. Tinker-Kulberg, L. Hwang, A. Szidon et al., 1998. The Polo-related kinase Cdc5 activates and is destroyed by the mitotic cyclin destruction machinery in S. cerevisiae. Curr. Biol. 8 497–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover, A., 1994. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. Cell 79 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix, O., 2001. The making and breaking of sister chromatid cohesion. Cell 106 137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix, O., J. M. Peters, M. W. Kirschner and D. Koshland, 1996. Anaphase initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by the APC-dependent degradation of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1p. Genes Dev. 10 3081–3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross, F. R., 2003. Two redundant oscillatory mechanisms in the yeast cell cycle. Dev. Cell 4 741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies, R. J., V. Chau and M. Kirschner, 1995. Ubiquitination of the G1 cyclin Cln2p by a Cdc34p-dependent pathway. EMBO J. 14 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, J. D., J. H. Toyn, A. L. Johnson and L. H. Johnston, 1994. P40SDB25, a putative CDK inhibitor, has a role in the M/G1 transition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 8 1640–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, G., H. Yu and M. W. Kirschner, 1998. Direct binding of CDC20 protein family members activates the anaphase-promoting complex in mitosis and G1. Mol. Cell 2 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz, R. D., R. H. Schiestl, A. R. Willems and R. A. Woods, 1995. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast 11 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmachl, M., C. Gieffers, A. V. Podtelejnikov, M. Mann and J. M. Peters, 2000. The RING-H2 finger protein APC11 and the E2 enzyme UBC4 are sufficient to ubiquitinate substrates of the anaphase-promoting complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 8973–8978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh, P. Y., H. H. Lim and U. Surana, 2000. Cdc20 protein contains a destruction-box but, unlike Clb2, its proteolysis is not acutely dependent on the activity of anaphase-promoting complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 267 434–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbsky, G. J., 2001. The mitotic spindle checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 11 R1001–R1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, D. M., and D. M. Roof, 2001. Degradation of the kinesin Kip1p at anaphase onset is mediated by the anaphase-promoting complex and Cdc20p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 12515–12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M. C., M. P. Torres, G. K. Schroeder and C. H. Borchers, 2003. Mnd2 and Swm1 are core subunits of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae anaphase-promoting complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278 16698–16705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt, E. R., and M. A. Hoyt, 2001. Cell cycle-dependent degradation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae spindle motor Cin8p requires APC(Cdh1) and a bipartite destruction sequence. Mol. Biol. Cell 12 3402–3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilioti, Z., Y. S. Chung, Y. Mochizuki, C. F. Hardy and O. Cohen-Fix, 2001. The anaphase inhibitor Pds1 binds to the APC/C-associated protein Cdc20 in a destruction box-dependent manner. Curr. Biol. 11 1347–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser, M., 1996. Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30 405–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irniger, S., 2002. Cyclin destruction in mitosis: a crucial task of Cdc20. FEBS Lett 532 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irniger, S., and K. Nasmyth, 1997. The anaphase-promoting complex is required in G1 arrested yeast cells to inhibit B-type cyclin accumulation and to prevent uncontrolled entry into S-phase. J. Cell Sci. 110 1523–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irniger, S., S. Piatti, C. Michaelis and K. Nasmyth, 1995. Genes involved in sister chromatid separation are needed for B-type cyclin proteolysis in budding yeast. Cell 81 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irniger, S., M. Baumer and G. H. Braus, 2000. Glucose and ras activity influence the ubiquitin ligases APC/C and SCF in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 154 1509–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, P. K., A. G. Eldridge, E. Freed, L. Furstenthal, J. Y. Hsu et al., 2000. The lore of the RINGs: substrate recognition and catalysis by ubiquitin ligases. Trends Cell Biol. 10 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang, Y. L., J. Huang, J. M. Peters, M. E. McLaughlin, C. Y. Tai et al., 1997. APC-mediated proteolysis of Ase1 and the morphogenesis of the mitotic spindle. Science 275 1311–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura, T., D. M. Koepp, M. N. Conrad, D. Skowyra, R. J. Moreland et al., 1999. Rbx1, a component of the VHL tumor suppressor complex and SCF ubiquitin ligase. Science 284 657–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi, T., and F. Yamao, 1998. An essential function of Grr1 for the degradation of Cln2 is to act as a binding core that links Cln2 to Skp1. J. Cell Sci. 111(Pt. 24): 3655–3661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, K. M., D. Fesquet, A. L. Johnson and L. H. Johnston, 1998. Budding yeast RSI1/APC2, a novel gene necessary for initiation of anaphase, encodes an APC subunit. EMBO J. 17 498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, J. R., W. A. Michaud, R. S. Sikorski and P. A. Hieter, 1994. Cdc16p, Cdc23p and Cdc27p form a complex essential for mitosis. EMBO J. 13 4321–4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverson, J. D., C. A. Joazeiro, A. M. Page, H. Huang, P. Hieter et al., 2000. The APC11 RING-H2 finger mediates E2-dependent ubiquitination. Mol. Biol. Cell 11 2315–2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew, D. J., and D. J. Burke, 2003. The spindle assembly and spindle position checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Genet. 37 251–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., 1999. Bifurcation of the mitotic checkpoint pathway in budding yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 4989–4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall, M. D., 1993. An inhibitor of p34CDC28 protein kinase activity from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 259 216–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumberg, D., R. Muller and M. Funk, 1995. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene 156 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth, K., J. M. Peters and F. Uhlmann, 2001. Splitting the chromosome: cutting the ties that bind sister chromatids. Novartis Found. Symp. 237 113–133, 133–138, 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho, T. T., and M. D. Mendenhall, 1994. An inhibitor of yeast cyclin-dependent protein kinase plays an important role in ensuring the genomic integrity of daughter cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14 3320–3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, A. M., and P. Hieter, 1999. The anaphase-promoting complex: new subunits and regulators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68 583–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, L. A., E. A. McCormack, S. W. Au, A. Paul, K. R. Willison et al., 2003. Doc1 mediates the activity of the anaphase-promoting complex by contributing to substrate recognition. EMBO J. 22 786–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, E. E., A. R. Willems, D. Sa, L. Kuras, D. Thomas et al., 1998. Cdc53 is a scaffold protein for multiple Cdc34/Skp1/F-box protein complexes that regulate cell division and methionine biosynthesis in yeast. Genes Dev. 12 692–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G., T. Hofken, J. Grindlay, C. Manson and E. Schiebel, 2000. The Bub2p spindle checkpoint links nuclear migration with mitotic exit. Mol. Cell 6 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J. M., 1999. Subunits and substrates of the anaphase-promoting complex. Exp. Cell Res. 248 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleger, C. M., E. Lee and M. W. Kirschner, 2001. Substrate recognition by the Cdc20 and Cdh1 components of the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes Dev. 15 2396–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, S., E. S. Hwang, R. Visintin and A. Amon, 1998. The regulation of Cdc20 proteolysis reveals a role for APC components Cdc23 and Cdc27 during S phase and early mitosis. Curr. Biol. 8 750–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabitsch, K. P., A. Toth, M. Galova, A. Schleiffer, G. Schaffner et al., 2001. A screen for genes required for meiosis and spore formation based on whole-genome expression. Curr. Biol. 11 1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M. D., F. Winston and P. Hieter, 1990 Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Rudner, A. D., and A. W. Murray, 2000. Phosphorylation by Cdc28 activates the Cdc20-dependent activity of the anaphase-promoting complex. J. Cell Biol. 149 1377–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner, A. D., K. G. Hardwick and A. W. Murray, 2000. Cdc28 activates exit from mitosis in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 149 1361–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, M., A. S. Lutum and W. Seufert, 1997. Yeast Hct1 is a regulator of Clb2 cyclin proteolysis. Cell 90 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, M., M. Neutzner, D. Mocker and W. Seufert, 2001. Yeast Hct1 recognizes the mitotic cyclin Clb2 and other substrates of the ubiquitin ligase APC. EMBO J. 20 5165–5175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwickart, M., J. Havlis, B. Habermann, A. Bogdanova, A. Camasses et al., 2004. Swm1/Apc13 is an evolutionarily conserved subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex stabilizing the association of Cdc16 and Cdc27. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 3562–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob, E., T. Bohm, M. D. Mendenhall and K. Nasmyth, 1994. The B-type cyclin kinase inhibitor p40SIC1 controls the G1 to S transition in S. cerevisiae. Cell 79 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J. V., and D. W. Cleveland, 2000. Waiting for anaphase: Mad2 and the spindle assembly checkpoint. Cell 103 997–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R., S. Jensen, L. M. Frenz, A. L. Johnson and L. H. Johnston, 2001. The Spo12 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a regulator of mitotic exit whose cell cycle-dependent degradation is mediated by the anaphase-promoting complex. Genetics 159 965–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama, M., W. Zachariae, R. Ciosk and K. Nasmyth, 1998. The Polo-like kinase Cdc5p and the WD-repeat protein Cdc20p/fizzy are regulators and substrates of the anaphase promoting complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 17 1336–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama, M., A. Toth, M. Galova and K. Nasmyth, 1999. APC(Cdc20) promotes exit from mitosis by destroying the anaphase inhibitor Pds1 and cyclin Clb5. Nature 402 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R. S., W. A. Michaud and P. Hieter, 1993. p62cdc23 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a nuclear tetratricopeptide repeat protein with two mutable domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13 1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibbens, R. V., and P. Hieter, 1998. Kinetochores and the checkpoint mechanism that monitors for defects in the chromosome segregation machinery. Annu Rev Genet 32 307–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra, D., D. M. Koepp, T. Kamura, M. N. Conrad, R. C. Conaway et al., 1999. Reconstitution of G1 cyclin ubiquitination with complexes containing SCFGrr1 and Rbx1. Science 284 662–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight, A. F., and A. W. Murray, 1997. The spindle assembly checkpoint in budding yeast. Methods Enzymol. 283 425–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z., B. Li, R. Bharadwaj, H. Zhu, E. Ozkan et al., 2001. APC2 Cullin protein and APC11 RING protein comprise the minimal ubiquitin ligase module of the anaphase-promoting complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 12 3839–3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, B. R., and D. P. Toczyski, 2003. Securin and B-cyclin/CDK are the only essential targets of the APC. Nat. Cell Biol. 5 1090–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufano, S., P. San-Segundo, F. del Rey and C. R. Vazquez de Aldana, 1999. SWM1, a developmentally regulated gene, is required for spore wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 2118–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufano, S., M. E. Pablo, A. Calzada, F. del Rey and C. R. Vazquez de Aldana, 2004. Swm1p subunit of the APC/cyclosome is required for activation of the daughter-specific gene expression program mediated by Ace2p during growth at high temperature in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 117 545–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshavsky, A., 1996. The N-end rule: functions, mysteries, uses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 12142–12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin, R., S. Prinz and A. Amon, 1997. CDC20 and CDH1: a family of substrate-specific activators of APC-dependent proteolysis. Science 278 460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodermaier, H. C., C. Gieffers, S. Maurer-Stroh, F. Eisenhaber and J. M. Peters, 2003. TPR subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex mediate binding to the activator protein CDH1. Curr. Biol. 13 1459–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., F. Hu and S. J. Elledge, 2000. The Bfa1/Bub2 GAP complex comprises a universal checkpoint required to prevent mitotic exit. Curr. Biol. 10 1379–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasch, R., and F. R. Cross, 2002. APC-dependent proteolysis of the mitotic cyclin Clb2 is essential for mitotic exit. Nature 418 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, K. S., H. C. Vodermaier, U. Jacob, C. Gieffers, M. Gmachl et al., 2001. Crystal structure of the APC10/DOC1 subunit of the human anaphase-promoting complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems, A. R., S. Lanker, E. E. Patton, K. L. Craig, T. F. Nason et al., 1996. Cdc53 targets phosphorylated G1 cyclins for degradation by the ubiquitin proteolytic pathway. Cell 86 453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeong, F. M., H. H. Lim, C. G. Padmashree and U. Surana, 2000. Exit from mitosis in budding yeast: biphasic inactivation of the Cdc28-Clb2 mitotic kinase and the role of Cdc20. Mol. Cell 5 501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]