Abstract

We found that a 46-kDa protein is highly expressed in an actinorhodin-overproducing Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) mutant (KO-179), which exhibited a low-level resistance to streptomycin. The protein was identified as S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) synthetase, which is a product of the metK gene. Enzyme assay revealed that SAM synthetase activity in strain KO-179 was 5- to 10-fold higher than in wild-type cells. The elevation of SAM synthetase activity was found to be associated with an increase in the level of intracellular SAM. RNase protection assay revealed that the metK gene was transcribed from two distinct promoters (p1 and p2) and that enhanced expression of the MetK protein in the mutant strain KO-179 was attributed to elevated transcription from metKp2. Strikingly, the introduction of a high-copy-number plasmid containing the metK gene into wild-type cells resulted in a precocious hyperproduction of actinorhodin. Furthermore, the addition of SAM to the culture medium induced Act biosynthesis in wild-type cells. Overexpression of metK stimulated the expression of the pathway-specific regulatory gene actII-ORF4, as demonstrated by the RNase protection assay. The addition of SAM also caused hyperproduction of streptomycin in Streptomyces griseus. These findings implicate the significant involvement of intracellular SAM in initiating the onset of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces.

Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) is the genetically best-characterized streptomycete (4, 34) and is frequently used as a model organism for studying the regulation of antibiotic production (5, 15). This strain produces at least four chemically distinct classes of antibiotics, two of which are pigmented: the blue polyketide actinorhodin (Act) and the red tripyrolle undecylprodigiosin (Red). This fact provides a feasible system for the study of pathway-specific and pleiotropic regulation of antibiotic synthesis.

We reported previously that introduction of certain str mutations, which is able to confer resistance to streptomycin, enhance Act production in Streptomyces lividans and S. coelicolor A3(2) (14, 37). Furthermore, the impaired ability to produce Act due to certain developmental mutations (relA, relC, and brgA) in S. coelicolor can be circumvented by introducing the str mutations (28, 30, 37). These str mutants are classified into two types. The type I mutants (rpsL mutants) have a mutation within the rpsL gene which encodes the ribosomal protein S12 and demonstrates a high-level of resistance (>100 μg/ml) to streptomycin. The type II mutants possess the wild-type rpsL gene and demonstrates a low level of resistance (5 to 10 μg/ml). Although a type II mutation in S. coelicolor KO-132 (relA str-1) had been genetically mapped on the genetic map (28), the actual mutation site (i.e., a mutated gene) remains unknown. However, the appearance of the type II mutants is frequent (ranging from 10−5 to 10−7), and their ability to produce Act is noticeably higher than in the rpsL mutants. Understanding the detailed mechanism that underline the altered cellular processes will lead to the elucidation of how enhanced production of Act occurs in the type II mutants. We report here the identification of a specific (46-kDa) protein, which is highly expressed in the S. coelicolor type II mutant KO-179. This protein is shown to be S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) synthetase (EC 2.5.1.6), a product of the metK gene. The possible involvement of the level of intracellular SAM in the regulation of Act production is also discussed, according to results from physiological and molecular level analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The strains of S. coelicolor A3(2) used in the present study were 1147 (prototrophic wild-type strain) and its derivative KO-179 (str-19) (14). Streptomyces griseus IFO13189, a wild-type prototrophic strain (26), was used for the production of streptomycin. E. coli strains DH5α and GM2163 were used for routine DNA manipulation. Spores from these S. coelicolor strains were harvested from cultures grown on GYM (37) or SFM (19) medium. R4 (37), R4C (R4 supplemented with 0.5% Casamino Acids), and R5− medium (17) were used for Act production. SMMS (19) was used for calcium-dependent antibiotic (CDA) production. When necessary, S. coelicolor cultures were grown on an agar medium covered with a cellophane sheet, after being inoculated with ca. 106 spores, and incubated at 30°C. Act, Red, and CDA were determined according to the method of Kieser et al. (19). Production of streptomycin was performed as described previously (26).

Isolation and manipulation of DNA and RNA.

Plasmid isolation, restriction enzyme digestion, ligation, and transformation of Escherichia coli and Streptomyces were carried out by the methods of Sambrook et al. (36) and Kieser et al. (19), respectively. PCR was performed by using a TaKaRa LA Taq or TaKaRa Ex Taq enzyme with GC Buffer I (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Unless stated otherwise, genomic DNA prepared from strain 1147 was used as a template for PCR. For RNA extraction, mycelium (ca. 50 to 100 mg of wet weight) from the plate culture (see above) was suspended in 1 ml of Isogen reagent (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan), and 0.2 g of zirconium beads (diameter, 0.5 mm) was added. The samples were treated at 2,000 rpm for 3 min in a Beads Homogenizer (Central Scientific Commerce, Tokyo, Japan), and then RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmid construction.

Plasmid pXEmetK, containing a metK-xylE transcriptional fusion element, was constructed as follows. The metK promoter region was generated by PCR with the primers PF1+BamHI (5′-GGATCCAGCGATCGGTTGTCGGGGTG-3′) and PR-1+HindIII (5′-AAGCTTCGGCTCCGAGGAGAAC-3′). A 435-bp PCR product was cloned in pCR2.1 TA cloning vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). After sequence confirmation, the metK promoter fragment was excised by BamHI and HindIII digestion and cloned into the pXE4 promoter probe vector (18) to generate pXEmetK. After passage through E. coli GM2163 (Δdam Δdcm), the plasmid pXEmetK was introduced into S. coelicolor strains.

The high-copy-number plasmid pMetK1, containing the S. coelicolor metK gene, was constructed as follows. The cosmid clone SCL6 (34) was digested with SapI, treated with Klenow enzyme to generate blunt ends, and digested with NotI, resulting in a 2.3-kb metK-containing fragment. This fragment was ligated with pBluescript II SK(+) treated with NotI and EcoRV, resulting in pBlueMetK2. The metK gene was excised from the pBluMetK2 by SacI and HindIII digestion and cloned in pIJ487 (43) treated with the same enzymes to generate pMetK1.

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2-D PAGE).

Cells were harvested from the R4 liquid culture, resuspended in lysis solution (8 M urea, 4% CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate}, 40 mM Tris base), and disrupted by sonication for 2 min. After centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatants were used as protein extract samples. A 100-μg portion of the total proteins was subjected to first-dimension isoelectric focusing (IEF) electrophoresis. IEF electrophoresis was performed with an Immobiline dry strip (pH 4 to 7, 11 cm; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.) by using a Multiphor II Electrophoresis Unit (Amersham Biosciences). An ExcelGel sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) Gradient 12-14 (Amersham Biosciences) was used for 2-D SDS-PAGE. Proteins were detected by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250.

Determination of intracellular SAM.

Intracellular SAM levels were determined by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography by a method described previously (32). Cells were grown on R5− agar covered with cellophane. At the times indicated (36, 48, 60, and 72 h after inoculation), the cellophane sheet with cells was pealed from the plate and immediately transferred to a petri dish containing 10 ml of 1 M formic acid, followed by standing at 4°C for 1 h. The formic acid was collected, filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter, and then lyophilized. The lyophilized samples were dissolved in a small amount of water and analyzed with a Capcell-Pak C18 column (4.6 by 250 mm; Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan).

Enzyme assays.

Cells harvested from plate culture were suspended in 0.2 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid buffer (pH 6.0), and sonicated. Crude cell extract was obtained by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and used for the enzyme assay. SAM synthetase was assayed by spectrophotometrically measuring pyrophosphate production by using the Sigma pyrophosphate reagent (21). XylE enzyme activity was assayed as described previously (19), except that cells were grown on R5− agar.

Western blot analysis.

A portion (15 μg) of total proteins was subjected to 15% (for ActII-ORF4 protein) or 12% (for ActI-ORF1 protein) polyacrylamide-sodium dodecyl sulfate gels. Western blot analyses were performed as described previously (16, 31, 46).

RNase protection assays.

A metK riboprobe was generated as follows. The SCL6.34c-metK intergenic region was amplified by PCR with the primers EcoRI-metKp-F1 (5′-CTCTGAATTCCCATTTGCTCGAAGGAGCAG-3′) and HindIII-metKp-R1 (5′-CTCTAAGCTTACCAGACCGGTGGTGATCA-3′) to produce a 406-bp fragment containing EcoRI and HindIII sites (indicated by underlining). This fragment was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and inserted into pUC19. The resultant plasmid (pMetKP2) was sequenced and used for PCR amplification with the primers M13(-40) and HindIII-metKp-R1 to produce a 439-bp fragment. A T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence was introduced into this fragment by using the Lig'nScribe no-cloning promoter addition kit (Ambion, Austin, Tex.), and in vitro transcription was carried out with a MAXIscript in vitro transcription kit (Ambion) and labeled with [α-32P]UTP (Amersham Biosciences). The metK riboprobe (449 nucleotide [nt]) contained a 62-nt nonhomologous sequence from the pUC19 multiple cloning site and T7 promoter sequence. A 257-bp fragment containing the hrdB promoter region was generated by PCR with the primers RPA-hrdB-F (5′-GATTGGGCGTAACGCTCTTG-3′) and RPA-hrdB-R (5′-CCATGACAGAGACGGACTCG-3′). A T7 promoter sequence was introduced to this 257-bp fragment by using the Lig'nScribe kit, and an in vitro transcription reaction was performed as described above. An actII-ORF4 riboprobe was generated from a 267-bp PCR fragment amplified with the primers RPA-actII-F (5′-AATCTGTTGAGTAGGCCTGTT-3′) and RPA-actII-R (5′-GTACACGTACGTCTGCAGC-3′) in a similar way.

RNA samples (20 μg each) were hybridized overnight at 42°C with labeled riboprobe (5 × 104 cpm) by using the RPA III RNase protection assay kit (Ambion). After hybridization, samples were digested with an RNase mixture (RNase A and RNase T1) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Digested samples were precipitated, redissolved in gel-loading buffer, and loaded on a 5% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel. 32P-labeled RNA molecular size markers were generated by in vitro transcription using a RNA Century Marker template sets (Ambion). Radioactivity on gels were quantitated with a STORM 860 image analyzer (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

Primer extension analysis.

Primer extension analysis was done as described in Sambrook et al. (36). The primer (5′-TCACGGACTCCGAGGTGAACAG-3′) was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Total RNA (40 μg) was hybridized with 5′ end-labeled primer (ca. 105 cpm) and used for the primer extension reaction. The extension products were analyzed in a sequencing gel (6% polyacrylamide-8 M urea) with sequencing ladders generated from the same primer.

RESULTS

2-D PAGE analysis of total proteins.

Several Act-overproducing mutants selected for low-level resistance to streptomycin have been isolated and characterized in our laboratory (14, 28, 37). These mutants, unlike the mutants selected for high-level resistance, have no mutation within the rpsL gene that encodes the ribosomal protein S12, even though resistance to streptomycin has been known to result frequently from mutations in the rpsL gene (14, 37). We tentatively designated the mutation(s) in these low-level str mutants as “ND.” KO-179 is a representative strain from the ND mutant group, which were derived from strain 1147, a prototrophic wild-type strain of S. coelicolor A3(2). KO-179 produces a greater amount of Act than the wild-type strain in both solid and liquid cultures but shows reduced sporulation (14).

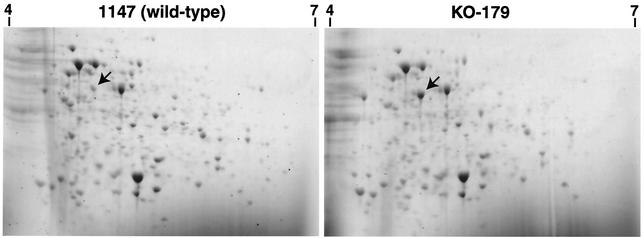

We first compared protein expression profiles from KO-179 and the wild-type strain 1147 by using 2-D PAGE. Strains were grown to early (6 h), middle (20 h), or late (32 h) growth phase in liquid R4 medium, and the total cellular proteins extracted were analyzed by 2-D PAGE in a pH range of between 4 and 7. We found that a 46-kDa protein exists in abundance in KO-179 but not in the wild-type strain, as indicated by the arrows in Fig. 1. The pI value of this protein was estimated to be 4.5 to 5.0. We also found that ActVI-ORF3, a putative protein for Act biosynthesis (4), increased five- to sevenfold as determined by 1-D PAGE (data not shown). The expression of this 46-kDa protein appeared to be temporal since a burst of expression was detected only in the late growth phase (20 to 32 h) but not in the early growth phase (6 h). Thus, we assumed that the 46-kDa protein may play a role during a late-growth-phase-specific cell event such as antibiotic production.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of total cellular proteins by 2-D PAGE. Cells were grown in liquid R4 medium and harvested at 30 h (the time of entry into the stationary phase). Total proteins from S. coelicolor 1147 (wild-type) and the mutant KO-179 were analyzed by 2-D PAGE. MetK protein is indicated by the arrows. The markers, 4 and 7, on the figures indicate the isoelectric pH points.

Identification of the 46-kDa protein.

For N-terminal sequencing, the 46-kDa protein spot was excised from the 2-D gel and analyzed on a protein sequencer. The N-terminal sequence was found to be XRRLFTXESVTE, which is highly homologous with the metK gene product, SAM synthetase (accession no. CAB76898). The S. coelicolor metK gene codes for a 404-amino-acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 43 kDa. The predicted isoelectric point for the MetK protein is 4.7. These values all agree well with the experimental data for our 46-kDa protein.

SAM synthetase activity and the level of intracellular SAM in KO-179.

To ascertain whether the level of SAM synthetase increased in the mutant strain KO-179, we measured the enzyme activity. Parent (strain 1147) and mutant (strain KO-179) strains were grown in R5− agar medium covered with cellophane, and mycelia were harvested at various growth phases, followed by measurement of SAM synthetase activity. It is evident from Table 1 that SAM synthetase activity in KO-179 increased remarkably throughout the whole-cell cycle, ranging from 5- to 10-fold, thus reflecting the observed overexpression of the MetK protein.

TABLE 1.

SAM synthetase activity and the level of intracellular SAM in S. coelicolor KO-179 and the parental strain 1147a

| Time (h) | SAM synthetase activity (mU/mg of protein)b

|

SAM level (pmol/mg [wet wt])

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1147 | KO-179 | 1147 | KO-179 | |

| 24 | 0.91 | 4.01 | ND | ND |

| 36 | 0.97 | 10.1 | 50.7 | 198.9 |

| 48 | 2.27 | 15.4 | 45.5 | 132.4 |

| 60 | 1.05 | 10.4 | 117.7 | 77.5 |

| 72 | 1.46 | 6.14 | 62.0 | 48.5 |

Cells were grown on R5− agar covered with cellophane. Samples were taken at the indicated times, and the SAM synthetase activity and intracellular SAM content were determined as described in Materials and Methods. ND, not determined due to an insufficient amount of cells.

One unit of activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that produced an change in optical density at 340 nm of 12.44/min.

We next asked whether or not the intracellular SAM level was actually altered upon the overexpression of SAM synthetase. Strains KO-179 and 1147 were grown on R5− agar medium as described above, and the intracellular SAM level was determined (see Materials and Methods). As expected, the level of intracellular SAM in KO-179 was found to be markedly elevated relative to the wild-type strain (Table 1). This was especially pronounced in the late growth phase (36 to 48 h), at which time Act production commences. These results led us to the hypothesis that the increased level of SAM may be responsible for the observed activation of Act biosynthesis.

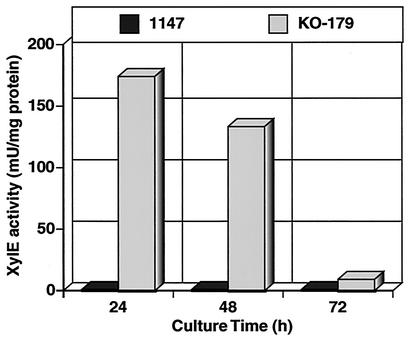

Transcription of the metK gene is elevated in KO-179.

To address the question whether overproduction of SAM synthetase in KO-179 is exerted at the transcription level, we monitored the expression of xylE (which encodes catechol dioxigenase) under the control of the metK promoter. Wild-type and KO-179 cells were transformed with pXEmetK, a xylE expression plasmid containing a 425-bp putative metK promoter fragment. In the plate assay, KO-179 cells containing pXEmetK was shown to produce a bright yellow color upon exposure to catechol when grown on R5− agar medium, whereas no catechol dioxigenase activity was detected in the wild-type strain containing the same plasmid. This finding indicates that the 425-bp metK promoter is functional and that transcription of the metK gene was significantly accelerated in the mutant strain KO-179. Quantitative assay revealed only slight catechol dioxigenase activity in the parental strain 1147 throughout the course of the experiment (Fig. 2). In contrast, significant catechol dioxigenase activity was detected when expression of the metk-xylE element was assessed in the ND mutant KO-179. The highest activity was found in the early-growth-phase cells, and the activity decreased gradually with time.

FIG. 2.

Expression of metK-xylE fusion element. The graph shows results for the quantitative catechol dioxygenase assays for expression of the metK-xylE fusion element in strains 1147 and KO-179. Cells were grown in R5− agar medium.

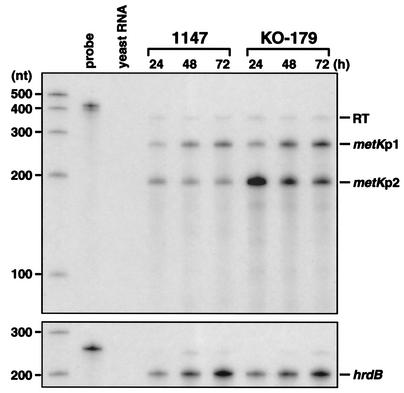

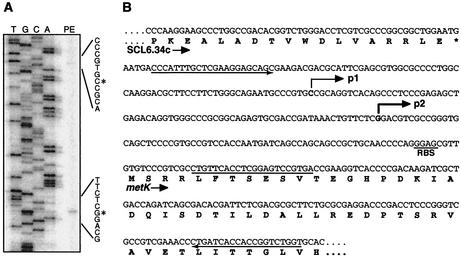

Expression of the metK gene was further examined by RNase protection assay with total RNA isolated from the indicated cells. A 449-nt riboprobe used in the RNase protection assay covers the SCL6.34c-metK intergenic region, including 62 nt of the nonhomologous tail that is derived from vector and T7 promoter sequences (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 3, three protected fragments (350, 260, and 195 nt) were detected from the RNA isolated from 1147 and KO-179. In our electrophoresis system, RNA fragments derived from Streptomyces sequences migrate faster than the RNA marker used in the experiment, and the relative mobilities differ by ca. 15% (data not shown). Therefore, actual sizes of the protected fragment should be about 390, 300, and 225 nt, respectively. The largest protected fragment that corresponds to full-length protection over the homologous region of the riboprobe (387 nt) apparently indicates readthrough transcription from the SCL6.34c gene, whereas the other two protected fragments are considered to represent transcription from their own promoters. Precise start sites of transcription were determined by primer extension analysis (Fig. 4A). The start sites identified were 147 and 75 nt upstream from the GTG translation start codon (for metKp1 and metKp2, respectively), which corresponds to the positions predicted from the result of RNase protection assay (Fig. 4B). Thus, the S. coelicolor metK gene is transcribed from two distinct promoters, in addition to transcriptional readthrough from the upstream gene SCL6.34c.

FIG. 3.

Expression of metK in strains 1147 and KO-179. Transcription of metK during growth on R5− agar medium was analyzed by RNase protection assay. Transcripts originating from two distinct metK promoters (metKp1 and metKp2) are indicated, together with readthrough transcription (RT) from the upstream gene (SCL6.34c). hrdB mRNA was determined as an internal control.

FIG. 4.

Transcription start points for metK. (A) Primer extension analysis of the transcription start points for metKp1 and metKp2. The start points assigned are indicated by asterisks. (B) Nucleotide sequence for the metK promoter region. Bent arrows indicate the transcription start points. The position at which the oligonucleotide used for the primer extension analysis annealed is underlined. The sequences from which primers were designed to generate the riboprobe for the RNase protection assay are denoted by the underline arrows.

The level of readthrough transcription was similar between KO-179 and the wild-type strain and was constant throughout the time course (Fig. 3). Transcription from metKp1 increased with time, and the expression level for KO-179 was somewhat higher than 1147. Interestingly, the amount of transcript generated from metKp2 was shown to be much greater in strain KO-179. The level of metKp2 transcript in KO-179 was about eightfold higher than strain 1147 in the early growth phase (24 h) and then decreased in the late growth phase. Transcription from metKp2 in strain 1147 was weak and constant. The observed expression pattern for metKp2 agrees well with the results of metK-xylE fusion assays (see above). These results suggest that enhanced expression of MetK protein in KO-179 is attributed to the elevated transcription from metKp2.

It was possible from the results described above that the mutant strain KO-179 may harbor a mutation in the promoter region of metK gene. However, sequencing analysis of the metK promoter region (and also metK open reading frame [ORF] region) could not detect any differences between KO-179 and the wild-type strain 1147 (data not shown).

Overexpression of the metK gene or addition of SAM causes overproduction of Act in wild-type cells.

Because the MetK protein was identified as the protein that was highly expressed in the Act-overproducing mutant KO-179, MetK may be involved in this phenotype. To assess this possibility, we introduced a high-copy-number plasmid containing the metK gene (pMetK1) into the wild-type strain 1147. Strikingly, introduction of pMetK1 into strain 1147 resulted in a precocious hyperproduction of Act, as determined in both solid culture (Fig. 5A) and liquid culture (data not shown). SAM synthetase activity from srain 1147/pMetK1 was twofold higher than cells carrying the vector plasmid pIJ487. Introduction of the metK promoter region alone into strain 1147 by using a multicopy plasmid did not influence Act production. Furthermore, introduction of pMeK1 into S. lividans TK21, a close relative of S. coelicolor A3(2), did induce Act production (data not shown). Strain 1147/pMetK1 (and also mutant strain KO-179) grew normally in minimal medium without demonstrating the need for methionine (data not shown). Also, there was no detectable difference in the level of resistance to streptomycin between strains 1147/pMetK1 and 1147/pIJ487 (MIC of streptomycin of 0.8 μg/ml for these strains but MIC of 5 μg/ml for strain KO-179), implying that the streptomycin-resistant phenotype in the ND mutant KO-179 did not result from the increase in intracellular SAM level.

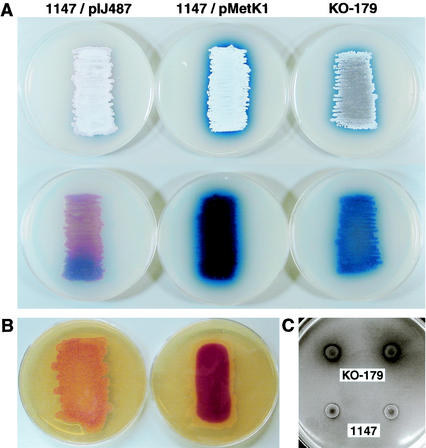

FIG. 5.

(A) Effect of the introduction of a multicopy metK plasmid on the production of Act in wild-type strain 1147. Strains were inoculated on R4C agar medium, followed by incubation for 4 days at 30°C. 1147/pIJ487 represents the vector control. The upper panel indicates the top of the plate, whereas the lower panel represents the reverse side of the plate. (B) Red production in strains 1147 and KO-179. Strains were inoculated on GYM agar and grown at 30°C for 2 days (for KO-179) or 3 days (for 1147). The reverse side of plates is shown. (C) CDA production in strains 1147 and KO-179. Portions (5 μl) of spore suspensions (ca. 105 spores) were spotted onto SMMS plates and incubated at 30°C for 48 h. CDA production was detected as described previously (19).

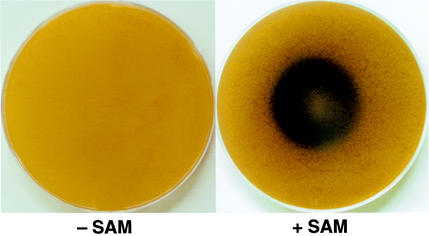

Next, we examined the effect of exogenously added SAM on Act production. If S. coelicolor could take up SAM, then SAM addition could mimic the effect of MetK overexpression, resulting in the overproduction of Act. As expected, exogenous SAM actually did cause Act overproduction in the wild-type strain 1147 (Fig. 6). The concentrations for SAM that were effective for Act overproduction were 1 mM or higher, as determined by using plates with fixed concentrations of SAM (data not shown). To assess the possibility that the observed effects were exerted by a metabolic product(s) generated from SAM rather than a direct activity of SAM, we tested the effects of various SAM-related metabolites on Act production. None of the S-adenosylhomocysteine, homocysteine, cysteine, homoserine, methionine, ornithine, spermidine, putrescine, and adenosine (added at 1 mM) showed any effects on the ability to produce Act (data not shown). Thus, we concluded that the elevated intracellular SAM level per se caused by overexpression of MetK is responsible for the enhanced production of Act in mutant strain KO-179.

FIG. 6.

Effect of exogenously added SAM. Strain 1147 spores were spread on GYM agar, and 3 mg of SAM (right plate) was placed in the center of the plate. The left plate shows a control plate without SAM. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 4 days. The reverse side of the plates is shown.

In considering the regulatory mechanism of SAM, it is important whether the effect of ND mutation in KO-179 is specific to Act or general to secondary metabolism in S. coelicolor. Therefore, we compared the ability of wild-type and mutant strains to produce Red and CDA, antibiotics produced by S. coelicolor. As shown in Fig. 5B, ND mutant KO-179 displayed a precocious hyperproduction of Red, in addition to an increased productivity of CDA (Fig. 5C).

The efficacy of exogenous addition of SAM was also demonstrated in another streptomycete, S. griseus, a producer of streptomycin. The addition of 1 mM SAM into the culture medium at the time of inoculation resulted in a hyperproduction of streptomycin, as determined with both synthetic medium and nutrient medium (data not shown).

Effect of MetK overproduction on the expression of ActII-ORF4.

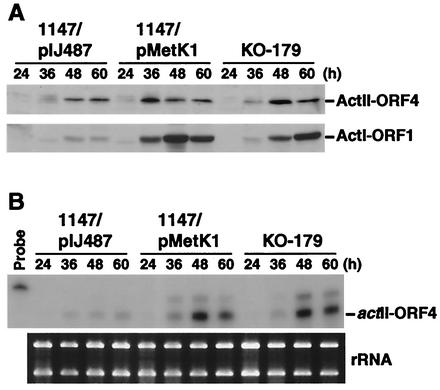

Expression of the Act biosynthetic genes is controlled by the pathway-specific regulatory gene, actII-ORF4 (12). The ActII-ORF4 protein, a product of the actII-ORF4 gene, has been characterized as an OmpR-like DNA binding protein that positively regulates the transcription of the Act biosynthetic genes (3). To assess the possible role for the overproduction of SAM synthetase on the expression of ActII-ORF4, we grew cells (1147/pMetK1, 1147/pIJ487, and KO-179) on R4C agar covered with cellophane. Cells were harvested at various growth phases, and ActII-ORF4 levels were determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 7A). Notably, metK overexpression was found to cause a significant increase in the expression of ActII-ORF4 compared to the control strain (1147/pIJ487). The mutant strain KO-179 also showed a marked increase in the expression of ActII-ORF4. The increase of ActI-ORF1 protein (a polyketide synthase subunit) was also more pronounced in both 1147/pMetK1 and KO-179 (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

Effect of the introduction of a multicopy metK plasmid on the expression of actII-ORF4. Cells were grown on R4C agar covered with cellophane and harvested at the indicated times. (A) Crude extracts were prepared and used for Western blot analysis to detect the ActII-ORF4 and ActI-ORF1 proteins. (B) RNA was isolated from the same culture and analyzed for the presence of actII-ORF4 mRNA by RNase protection assay. An ethidium bromide-stained gel containing 1 μg of RNA in each lane demonstrates the integrity of the RNA preparation.

Finally, we conducted an RNase protection assay for the actII-ORF4 transcript by by using total RNA isolated from the cells used for Western blot analysis (see above). Compared to the control strain 1147/pIJ487, there was a marked increase in actII-ORF4 transcription in both 1147/pMetK1 and KO-179 (Fig. 7B). Thus, overexpression of metK, which in turn leads to an elevated intracellular SAM level, activates transcription of the pathway-specific regulatory gene, actII-ORF4.

DISCUSSION

The importance of SAM synthetase activity (and thus the level of SAM) in microbial development processes was first proposed 20 years ago by Ochi et al. (27, 29), particularly focusing on antibiotic production and sporulation in Streptomyces griseoflavus and Bacillus subtilis, respectively. The results described here establish the significance of SAM synthetase activity in initiating antibiotic production in S. coelicolor A3(2). Supporting this idea is the fact that streptomycin production by S. griseus is also enhanced by the addition of SAM to the culture medium. SAM is known to be the methyl donor for the methylation of cytosine and adenosine bases in DNA, rRNA, and tRNA, of various proteins, and of small molecules that are important in both lower and higher organisms (8, 25, 35, 42). Thus, the SAM synthetase is thought to be an essential enzyme for the viability of E. coli (44) and B. subtilis (47). Overexpression of the SAM synthetase gene in E. coli or B. subtilis is known to cause methionine auxotrophy (44, 47). An explanation for this auxotrophy is that overexpression of SAM synthetase depletes the intracellular methionine pool, either by consuming it to synthesize SAM or by repressing the methionine biosynthetic genes. In fact, SAM has been shown to be a corepressor in the mehionine regulation system in E. coli (13). Although B. subtilis showed a 6-fold increase in SAM synthetase activity that resulted in methionine auxotrophy, the S. coelicolor strain KO-179 produced 10-fold-greater SAM synthetase than did the wild-type strain (Table 1) without affecting growth as examined in minimal medium. Therefore, it is of interest to determine whether SAM acts as a corepressor in the methionine regulation system in Streptomyces.

As shown by both the metK-xylE fusion analysis and the RNase protection assay, enhanced expression of MetK protein in KO-179 is apparently achieved at the transcriptional level by activation of a specified (metKp2) promoter. The start site for the metKp1 transcript is preceded by a −10 region (CAGAAT) that is similar to the consensus sequence (TAGYYT, Y = G or A) deduced from streptomycete promoters. This consensus sequence is probably recognized by the major RNA polymerase that contains sigma HrdB (38). However, the presence of the recognizable −35 sequence, which is often found in typical HrdB-dependent promoters, is lacking. The metKp2 also lacks obvious sequence similarity with other known streptomycete promoters in the −10 and −35 region. Although maximum SAM synthetase activity in KO-179 was detected at 48 h (Table 1), transcription from metKp2 reduced gradually after 24 h (Fig. 3). This implies that accumulation of the MetK protein during this period occurred. Since the metK promoter region in KO-179 has been shown not to have a mutation, it is conceivable that the enhanced transcription from metKp2 in KO-179 may be caused by an alteration in quality and/or quantity of a presumptive transcription regulator for metK, and this may be how the ND mutation functions to increase the production of Act.

Most interestingly, introduction of the multicopy metK plasmid into wild-type cells led to a remarkably abundant production of Act (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the addition of SAM to the culture medium also induced Act biosynthesis (Fig. 6). Thus, enhanced Act production in mutant strain KO-179 is attributed, at least in part, to the overexpression of MetK protein, leading to an elevation of intracellular SAM level. In agreement with our conclusion, Kim et al. (20) reached a similar conclusion in working with Streptomyces spectabilis, a spectinomycin producer. These authors found that introduction of a multicopy plasmid containing the S. spectabilis metK gene into S. lividans TK23 can induce Act production in this organism. Also, we demonstrated in the present study the efficacy of propagating the S. coelicolor metK gene in activating the Act production in S. lividans TK21 (see Results). Although S. lividans, a species closely related to S. coelicolor A3(2), carries the entire clusters for Act in its genome, it normally produces less or no Act throughout the whole-cell cycle. Therefore, the propagation of metK gene is effective not only for the enhancement of Act production (as seen in S. coelicolor) but also for the activation of silent gene(s) (as seen in S. lividans), implicating an intrinsic role for SAM syntetase in microbial secondary metabolism. This proposal can be supported by the fact that ND mutation in strain KO-179 was capable of elevating the ability to produce Red and CDA (Fig. 5B and C) in addition to Act.

There are several reports that indicate possible involvement of intracellular SAM in the regulation of antibiotic production (9, 11, 22, 23, 29, 41, 45). Ochi et al. (29) showed previously that exogenous addition of SAM partially restored a defect in the bicozamycin production in certain arginine auxotrophic mutant of S. griseoflavus. In addition, the negative effect of methionine on the biosynthesis of antibiotics containing methyl or methoxy groups has been reported (9, 11, 22, 23, 41, 45). Recently, Kim et al. (22) found that the addition of methionine to the culture medium lowered the production of rapamycin but increased the production of demethylrapamaycin in Streptomyces hygroscopicus. These authors also revealed that methionine represses the synthesis of methyltransferase, which catalyzes the conversion of demethylrapamycin to rapamycin, in addition to the repression of SAM synthetase itself. A decrease in the level of SAM caused by the repression of SAM synthetase is likely to be responsible for the reduced expression of the methyltransferase. The repressive effect of methionine on the production of other antibiotics may be accounted for by a similar mechanism. However, since the Act (and also bicozamycin) biosynthetic pathway does not contain any steps that require SAM as a methyl donor, the mechanism by which intracellular SAM level affects Act and bicozamycin production is apparently different from the case of rapamycin as described above. The fact that the increased SAM level can activate the transcription of the regulatory gene actII-ORF4 for Act production (see below) supports this notion.

The principal regulation of Act production in S. coelicolor appears to be the availability of the pathway-specific transcriptional regulatory protein ActII-ORF4, threshold concentration of which is required for efficient transcription of its cognate biosynthetic structural genes. The fact that metK overexpression induces transcription of the actII-ORF4 is important to note. Several genes have been identified in S. coelicolor that are required for both antibiotic production and morphological differentiation (bld genes) (5, 7, 15). Also, a number of genes that regulate only antibiotic production have been isolated (1, 2, 6, 10, 24, 33). Certain mutations in these genes were shown to affect (usually reduce) transcription of the actII-ORF4 gene (1, 10). Although there is no evidence at present for the existence of a methyltransferase involved in the regulation of antibiotic production, SAM-dependent protein methylation may play a role in controlling the activity of the regulatory proteins that are encoded by such developmental genes. Alternatively, it is possible that DNA or RNA methylation is involved in the expression of these regulatory genes. For example, the extent of methylation of a particular macromolecule (e.g., a particular DNA region) could determine the probability with which a second macromolecule (e.g., a repressor or an activator) can bind to the first, eventually leading to significant alteration of gene expression, in analogy with the known mechanism in E. coli (42). Another possibility is that SAM served as a substrate in the biosynthesis of a γ-butyrolactone autoregulator, SCB1 (39, 40), resulting in a stimulation of antibiotic production by S. coelicolor. A number of observations in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (8, 25, 35, 42) may guide the search for the methylated molecule that controls initiation of the secondary metabolism onset. Apart from the notion described above that refers to the role of SAM as a methyl donor, SAM might directly be involved in the regulation of Act synthesis as a corepressor or an inducer, as has been demonstrated for methionine regulon expression in E. coli (13). It is important to point out that SAM affects morphological differentiation in S. lividans, in addition to antibiotic production, in the metK gene-propagated cells, as demonstrated by Kim et al. (20). These findings agree with our results that ND mutant KO-179 had a reduced ability to form aerial mycelium (Fig. 5A) and are consistent with the previous work with B. subtilis that sporulation of this organism is prevented by SAM at concentrations of ≥1 mM (27). It is intriguing to study whether the expression level of regulatory genes for morphological differentiation (e.g., bldD and whiG in S. coelicolor and spo0A and codY in B. subtilis), like that of the actII-ORF4 gene, are controlled by the intracellular SAM level or not. We have recently found that another ND mutant KO-132 (relA str-1) also overproduces SAM synthetase (unpublished data). KO-132 had been isolated from the relA mutant M570 by virtue of low-level streptomycin resistance accompanied by complete restoration of impaired Act production due to the relA mutation (28, 37). These results implicate that SAM may exert its effect in a wide variety of biological events by controlling the gene expression in microorganisms as well as eukaryotic cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Organized Research Combination Systems of the Science and Technology Agency of Japan.

We are grateful to N. Saito for assistance in several experiments and to J. W. Suh for valuable discussions just before submission of this study.

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to David A. Hopwood upon his retirement from the John Innes Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aceti, D. J., and W. C. Champness. 1998. Transcriptional regulation of Streptomyces coelicolor pathway-specific antibiotic regulators by the absA and absB loci. J. Bacteriol. 180:3100-3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aigle, B., A. Wietzorrek, E. Takano, and M. J. Bibb. 2000. A single amino acid substitution in region 1.2 of the principal sigma factor of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) results in pleiotropic loss of antibiotic production. Mol. Microbiol. 37:995-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias, P., M. A. Fernandez-Moreno, and F. Malpartida. 1999. Characterization of the pathway-specific positive transcriptional regulator for actinorhodin biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) as a DNA-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 181:6958-6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley, S. D., K. F. Chater, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, G. L. Challis, N. R. Thomson, K. D. James, D. E. Harris, M. A. Quail, H. Kieser, D. Harper, A. Bateman, S. Brown, G. Chandra, C. W. Chen, M. Collins, A. Cronin, A. Fraser, A. Goble, J. Hidalgo, T. Hornsby, S. Howarth, C. H. Huang, T. Kieser, L. Larke, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, S. O'Neil, E. Rabbinowitsch, M. A. Rajandream, K. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, D. Saunders, S. Sharp, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Taylor, T. Warren, A. Wietzorrek, J. Woodward, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, and D. A. Hopwood. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bibb, M. 1996. 1995 Colworth Prize Lecture. The regulation of antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Microbiology 142:1335-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brian, P., P. J. Riggle, R. A. Santos, and W. C. Champness. 1996. Global negative regulation of Streptomyces coelicolor antibiotic synthesis mediated by an absA-encoded putative signal transduction system. J. Bacteriol. 178:3221-3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chater, K. F. 1993. Genetics of differentiation in Streptomyces. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:685-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang, P. K., R. K. Gordon, J. Tal, G. C. Zeng, B. P. Doctor, K. Pardhasaradhi, and P. P. McCann. 1996. S-Adenosylmethionine and methylation. FASEB J. 10:471-480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Favret, M. E., and L. D. Boeck. 1992. Effect of cobalt and cyanocobalamin on biosynthesis of A10255, a thiopeptide antibiotic complex. J. Antibiot. 45:1809-1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Floriano, B., and M. Bibb. 1996. afsR is a pleiotropic but conditionally required regulatory gene for antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 21:385-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gairola, C., and L. Hurley. 1976. The mechanism for the methionine mediated reduction in anthramycin yields in Streptomyces refuincus fermentations. Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2:95-101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gramajo, H. C., E. Takano, and M. J. Bibb. 1993. Stationary-phase production of the antibiotic actinorhodin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) is transcriptionally regulated. Mol. Microbiol. 7:837-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene, R. C. 1996. Biosynthesis of methionine, p. 542-560. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 14.Hesketh, A., and K. Ochi. 1997. A novel method for improving Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) for production of actinorhodin by introduction of rpsL (encoding ribosomal protein S12) mutations conferring resistance to streptomycin. J. Antibiot. 50:532-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopwood, D. A., K. F. Chater, and M. J. Bibb. 1995. Genetics of antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), a model streptomycete. Bio/Technology 28:65-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu, H., Q. Zhang, and K. Ochi. 2002. Activation of antibiotic biosynthesis by specified mutations in the rpoB gene (encoding the RNA polymerase β subunit) of Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 184:3984-3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, J., C. J. Lih, K. H. Pan, and S. N. Cohen. 2001. Global analysis of growth phase responsive gene expression and regulation of antibiotic biosynthetic pathways in Streptomyces coelicolor using DNA microarrays. Genes Dev. 15:3183-3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingram, C., M. Brawner, P. Youngman, and J. Westpheling. 1989. xylE functions as an efficient reporter gene in Streptomyces spp.: use for the study of galP1, a catabolite-controlled promoter. J. Bacteriol. 171:6617-6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical streptomyces genetics. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, England.

- 20.Kim, D.-J., J.-H. Huh, Y.-Y. Yang, C.-M. Kang, I.-H. Lee, C.-G. Hyun, S.-K. Hong, and J.-W. Suh. 2002. The accumulation of S-adenosyl-l-methionine enhances production of actinorhodin but inhibits sporulation in Streptomyces lividans TK23. J. Bacteriol. 185:•••-•••. ([JB 740-02, this issue].) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Kim, H. J., T. J. Balcezak, S. J. Nathin, H. F. McMullen, and D. E. Hansen. 1992. The use of a spectrophotometric assay to study the interaction of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase with methionine analogues. Anal. Biochem. 207:68-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, W. S., Y. Wang, A. Fang, and A. L. Demain. 2000. Methionine interference in rapamycin production involves repression of demethylrapamycin methyltransferase and S-adenosylmethionine synthetase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2908-2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam, K. S., J. A. Veitch, J. Golik, B. Krishnan, S. E. Klohr, K. J. Volk, S. Forenza, and T. W. Doyle. 1993. Biosynthesis of esperamicin A1, an enediyne antitumor antibiotic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115:12340-12345. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, P. C., T. Umeyama, and S. Horinouchi. 2002. afsS is a target of AfsR, a transcriptional factor with ATPase activity that globally controls secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 43:1413-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levit, M. N., Y. Liu, and J. B. Stock. 1998. Stimulus response coupling in bacterial chemotaxis: receptor dimers in signalling arrays. Mol. Microbiol. 30:459-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochi, K. 1987. Metabolic initiation of differentiation and secondary metabolism by Streptomyces griseus: significance of the stringent response (ppGpp) and GTP content in relation to A factor. J. Bacteriol. 169:3608-3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochi, K., and E. Freese. 1982. A decrease in S-adenosylmethionine synthetase activity increases the probability of spontaneous sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 152:400-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochi, K., and Y. Hosoya. 1998. Genetic mapping and characterization of novel mutations which suppress the effect of a relC mutation on antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Antibiot. 51:592-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochi, K., Y. Saito, K. Umehara, I. Ueda, and M. Kohsaka. 1984. Restoration of aerial mycelium and antibiotic production in a Streptomyces griseoflavus arginine auxotroph. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:2007-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochi, K., D. Zhang, S. Kawamoto, and A. Hesketh. 1997. Molecular and functional analysis of the ribosomal L11 and S12 protein genes (rplK and rpsL) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:488-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okamoto, S., and K. Ochi. 1998. An essential GTP-binding protein functions as a regulator for differentiation in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 30:107-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Payne, S. H., and B. N. Ames. 1982. A procedure for rapid extraction and high-pressure liquid chromatographic separation of the nucleotides and other small molecules from bacterial cells. Anal. Biochem. 123:151-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price, B., T. Adamidis, R. Kong, and W. Champness. 1999. A Streptomyces coelicolor antibiotic regulatory gene, absB, encodes an RNase III homolog. J. Bacteriol. 181:6142-6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redenbach, M., H. M. Kieser, D. Denapaite, A. Eichner, J. Cullum, H. Kinashi, and D. A. Hopwood. 1996. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 21:77-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reisenauer, A., L. S. Kahng, S. McCollum, and L. Shapiro. 1999. Bacterial DNA methylation: a cell cycle regulator? J. Bacteriol. 181:5135-5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., T. Maniatis, and E. F. Fritsch. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 37.Shima, J., A. Hesketh, S. Okamoto, S. Kawamoto, and K. Ochi. 1996. Induction of actinorhodin production by rpsL (encoding ribosomal protein S12) mutations that confer streptomycin resistance in Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 178:7276-7284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strohl, W. R. 1992. Compilation and analysis of DNA sequences associated with apparent streptomycete promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:961-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takano, E., R. Chakraburtty, T. Nihira, Y. Yamada, and M. J. Bibb. 2001. A complex role for the γ-butyrolactone SCB1 in regulating antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 41:1015-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takano, E., T. Nihira, Y. Hara, J. J. Jones, C. J. Gershater, Y. Yamada, and M. Bibb. 2000. Purification and structural determination of SCB1, a γ-butyrolactone that elicits antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Biol. Chem. 275:11010-11016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uyeda, M., and A. L. Demain. 1988. Methionine inhibition of thienamycin formation. J. Ind. Microbiol. 3:57-59. [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Woude, M., B. Braaten, and D. Low. 1996. Epigenetic phase variation of the pap operon in Escherichia coli. Trends. Microbiol. 4:5-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward, J. M., G. R. Janssen, T. Kieser, M. J. Bibb, and M. J. Buttner. 1986. Construction and characterization of a series of multi-copy promoter-probe plasmid vectors for Streptomyces using the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene from Tn5 as indicator. Mol. Gen. Genet. 203:468-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei, Y., and E. B. Newman. 2002. Studies on the role of the metK gene product of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1651-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williamson, J. M., E. Inamine, K. E. Wilson, A. W. Douglas, J. M. Liesch, and G. Albers-Schonberg. 1985. Biosynthesis of the beta-lactam antibiotic, thienamycin, by Streptomyces cattleya. J. Biol. Chem. 260:4637-4647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, J., Y. Tozawa, C. Lai, H. Hayashi, and K. Ochi. 2002. A rifampicin resistance mutation in the rpoB gene confers ppGpp-independent antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Genet. Genomics 268:179-189. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Yocum, R. R., J. B. Perkins, C. L. Howitt, and J. Pero. 1996. Cloning and characterization of the metE gene encoding S-adenosylmethionine synthetase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:4604-4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]